Box 1. Current health care trends, evidence and policies.

Shifting demographics

Multimorbidity/polypharmacy

Decommissioning (deprescribing)

Government policies and strategies: patient centred, integrated health care system, fiscal restraint, evidenceinformed changes

Patient restraint, evidence

Understanding, monitoring and improving health care quality, including safety

Engaging patients in health care planning and policy

Advances in technology

There has never been a greater need for people to access high-quality expertise about the effectiveness, safety and use of medications. While drugs improve health and save lives, they are not without risk.1-4 The collective influence of current health care trends and policies compels the profession of pharmacy to make fundamental changes in how it carries out its professional role to effectively and safely meet society’s health care needs.

The objectives of this article are to describe recent health care trends, evidence and policies and to identify opportunities for the profession of pharmacy. We pay particular attention to opportunities that use the full scope of pharmacy practice to make a difference in people’s lives.

Current health care trends

The modern pharmacist is largely responsible for helping patients navigate an increasingly complex and costly health care system, particularly with respect to medications. Demographic shifts have led to a situation where older adults now outnumber children under 15 years of age and 1 in 5 Canadians are immigrants, with mixed education and language ability.5,6 Polypharmacy is also commonplace in Canada, with 2 in 3 people over 65 taking more than 5 medications.7 Drug therapy problems are common, largely preventable and clinically harmful, and they present an increasing burden to our health care system. Approximately 1 in 50 people have had a preventable adverse drug event8 leading to emergency room visits9 and increased costs to the health care system.10 Total drug spending in Canada was estimated to be $39.8 billion in 2017 and made up the second largest share of health care expenditures.11 The growth in use of health care services, including medications, has led to a general movement to decommissioning of specific health care services, including the reduction or stopping of medications where they may be doing more harm than providing benefit or where evidence for benefit is weak.

Technology is rapidly changing the way health care services are provided. Many pharmacies allow patients to access their own dispensing records. This allows for ease of online ordering of prescriptions and associated home delivery. Drug monitoring, disease monitoring, disease detection and pharmacogenetics are becoming more commonplace in community pharmacies.12 Most physicians use electronic records,13,14 and almost 20% of Canadian physicians can exchange patient summaries electronically with other physicians.15 As pharmacies develop improved technology, the integration of health care provider records and the emergence of patient-controlled or viewable health records are important areas of health care transformation. The planned national e-prescribing system will improve patient and provider access to more complete medication records and serve as a platform for many functions beyond medication management, such as e-referrals, patient bookings and interclinician messaging.15

Government policies and strategies in Ontario,16,17 Alberta,18 British Columbia19 and Saskatchewan20 are driving a patient-centred transformation of health care across Canada. Recent health policies encourage improved integration of the health care system and enhanced patient and community engagement in health policy and practice. Mental health is a dedicated policy focus in Canada.21-23 There is an increasing emphasis on using evidence to inform health policy.24-26 Inclusion of the patient voice in health care planning is becoming more commonplace. Scope of practice has expanded for several frontline health care providers, including prescribing by nurses and pharmacists.

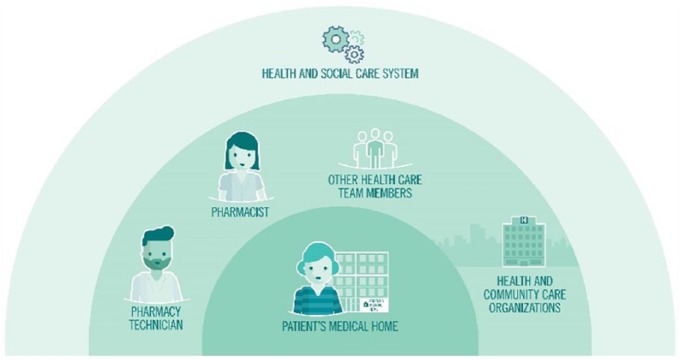

The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) vision of the Patient’s Medical Home (PMH)27 is another influential driver of organizational change within health care. The largest demonstrations of the PMH vision in Canada are through Family Health Teams28 in Ontario, Family Medicine Groups (groupe de médecine de famille [GMFs]) in Quebec29 and Primary Care Networks (PCNs) in Alberta.30 A PMH primary care practice offers care that is intended to be seamless and centred on individual patients’ needs, within their community, throughout every stage of life and integrated with other health services. A primary care practice often includes an organized group of family physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other health care providers, who work together in one centre or virtually. Unfortunately, the PMH model places community pharmacy and other health care organizations outside of the primary care PMH (Figure 1) but still part of a patient’s circle of care.

Figure 1.

The relationship of the profession of pharmacy to the patient’s medical home within the health care system

There is increased emphasis on understanding and monitoring health care quality in almost all health sectors. Jurisdictions such as Saskatchewan31 and Ontario32 have formal Health Quality Organizations that are advisors to the provincial governments and health care system organizations on health care quality. For example, Health Quality Ontario (HQO) monitors and reports on health system performance, provides guidance on quality issues, assesses evidence to determine what constitutes optimal care and engages with patients to give them a voice in shaping a quality health system and promote continuous quality improvement.

It is revealing that pharmacy as a key health care profession is almost invisible or nonexistent within more recent health policy initiatives. These gaps identify the necessity for pharmacy stakeholders such as the provincial pharmacy advocacy organizations to assume a better advocacy role with respect to the development of pharmacy practice. Pharmacy has an established evidence base that supports the health and cost benefits of pharmacist activities in many settings, including community, primary care team, long-term care and hospital settings.33-42 For example, medication reviews have been shown to be useful in improving the management of diabetes or hypertension, overall appropriateness of medications prescribed and medication discrepancies, but they show mixed effects for other outcomes.43-48 Hospital pharmacist medication review reduces hospital readmission49 and reduces length of hospital stay.50 Community pharmacist–based targeted interventions, including those for cardiovascular care, renal disease, dyslipidemia, smoking cessation and diabetes care, improve outcomes for people with chronic diseases.51-54 Highlighting opportunities for the profession of pharmacy to contribute to quality medication management can increase the potential of Canada’s 42,500 pharmacists55 (the third largest health care profession after nurses and physicians), who remain an incredibly underused health resource.56

Pharmacy services

Canadians visit their pharmacies often; the average pharmacy dispenses 54,350 prescriptions each year.57 Pharmacists provide a broad set of patient-focused clinical activities within a variety of health care settings, including comprehensive medication reviews (including diabetes-focused reviews), development of comprehensive care plans, independent prescribing (including renewing and adapting) prescriptions, providing prescribing recommendations, administering vaccines, counselling and prescribing for smoking cessation and providing targeted clinical services (e.g., anticoagulation, antimicrobial stewardship, health coaching).58

Data from the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network (OPEN) research group and others demonstrate that uptake of community pharmacist–delivered medication reviews and vaccinations in Ontario is high.59-62 However, OPEN’s work has also uncovered challenges in community pharmacy service implementation, including delivery of medication review services away from those with more complex health situations towards younger individuals with fewer comorbidities and the lack of documented follow-up after initial assessment.63-65

Organizational-level considerations in pharmacy

Pharmacy is a self-regulated health care profession. Each jurisdiction has an organization in place that is responsible for serving and protecting the public and to hold pharmacists and pharmacy technicians accountable to the established legislation, standards of practice, code of ethics and policies and guidelines relevant to pharmacy practice.

While pharmacy is practised in diverse public and private settings, the for-profit community pharmacy sector employs a large proportion of pharmacists and technicians.66 As the broader health system reform continues, several key themes continue to emerge for the community pharmacy sector. Beyond the different corporate structures in community pharmacy itself, the primary health care sector within which community pharmacy operates is also extraordinarily complicated. Patchwork funding and governance models among governments, employers, private citizens and third-party payers create tension but also opportunities for innovation and professional evolution. As government and private payers continue to put downward pressure on professional fees and as the number and range of pharmacies (particularly in urban and suburban areas) continue to increase, community pharmacies are working to find efficiencies to support operations and current levels of profitability. The physical structure and workflow systems of most community pharmacies are still oriented towards high-volume transactional dispensing practice. New practice models are evolving to fundamentally shift the nature of community practice by decoupling the compounding and dispensing functions of the profession of pharmacy from the medication management/cognitive services functions. Emerging trends, such as “central fill” and quasi-automated call centres to manage refills, will have an impact on the numbers and types of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians required and on the physical design of community pharmacies.

Approach used to identify opportunities for the profession of pharmacy in the future

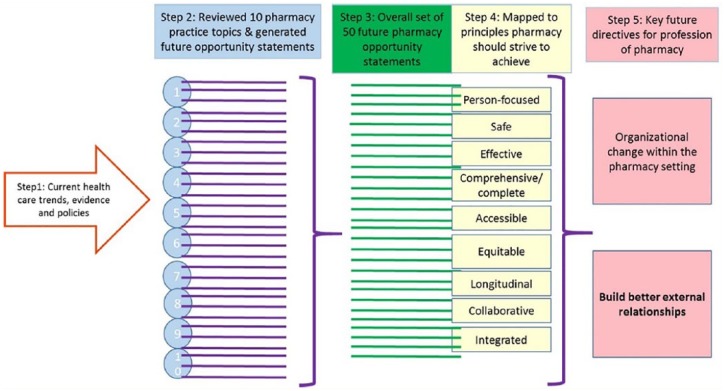

A 5-step process was used to identify opportunities for the profession of pharmacy in the future (Figure 2). First, current health care trends, evidence and policies were considered to identify an overarching set of principles the profession of pharmacy should strive to achieve. Second, 10 topics that represent different aspects of professional pharmacy practice were examined to generate topic-specific future opportunity statements for the profession of pharmacy (Appendix 1). Topics and authors were chosen by 3 of the authors (LD, NW and ZA) based on the combination of review of emerging health care trends, major areas of focus of the OPEN and expertise of the author group. Although not all-encompassing, the list service-oriented topics (e.g., medication review, prescribing, immunization/injections), health care trend topics (substance use disorders, deprescribing) and health system organization topics (e.g., quality improvement, e-health) were felt to be broad and diverse enough to draw out directions for the profession of pharmacy when examined as a collection. One author took primary responsibility for generating an overview for a specific topic. This included the current context and topic-specific future opportunity statements that identify existing strengths within the profession of pharmacy and how these strengths can best serve and protect the public when considering health care trends, evidence and policies. The 10 topics were chosen intentionally to encourage future-oriented thinking for the pharmacy profession over the next 5 to 10 years while simultaneously grounding thinking in the present context. It was felt that this approach would provide inspiration for how the profession of pharmacy can evolve from its current state to a better future. Third, the topic-specific future opportunity statements for the profession of pharmacy were combined across the topics to generate an overall set of 50 future opportunity statements for the profession of pharmacy. Fourth, the set of future opportunity statements was mapped onto the overarching set of principles the profession of pharmacy should strive to achieve that was identified after considering current health care trends, evidence and policies. Fifth, deliberation on the set of 50 future opportunity statements generated 2 summary themes that emerged as the key future directives for the profession of pharmacy in the coming 5 to 10 years. The author group exchanged topic summaries and held 10 meetings (participants varied across meetings) to discuss each topic and the overall set of future opportunity statements and summary themes. The majority of participants attended a face-to-face introductory meeting to discuss initial ideas and refine the topics. The rest of the meetings were convened by teleconference to discuss the individual topics based on a 10-minute verbal presentation and accompanying written summary provided by the author (Appendix 1) (earlier in the process) or the summative analysis (later in the process). Formal notes were circulated to all group members.

Figure 2.

Description of the steps used to generate the future opportunity statements and summary themes

Principles that the profession of pharmacy should strive to achieve

The set of principles that the profession of pharmacy should strive to achieve were identified to be person focused, effective, safe, comprehensive/complete, longitudinal, collaborative, equitable, accessible and integrated. These principles act as a guide to the provision of care delivered by the profession of pharmacy to overcome the “challenge” to the profession of pharmacy that was generated earlier based on current health care trends, evidence and policies. These principles are essential, as they have a significant impact with respect to patients being served through safer and more effective care. These principles apply to pharmacists working in all practice settings. These principles were considered and then used to develop challenge statements for the profession of pharmacy.

Future opportunities that support principles the profession of pharmacy should strive to achieve

The 50 future opportunity statements are provided in Appendix 2. These future opportunity statements can be considered by pharmacists working in all practice settings.

|

Challenge statement for the profession of pharmacy:

Recent health care trends and policies challenge pharmacists to provide safe, effective, comprehensive/complete and person-focused care that is accessible and equitable for all. By adopting a longitudinal and collaborative approach, pharmacists can also ensure that the provision of care is integrated across the health care system and for all stakeholders. |

Future directions for the profession of pharmacy

Two summary themes, organizational change and better external relationships, emerged as future directions the profession of pharmacy can take over the coming 5 to 10 years that will transform how pharmacy tackles the medication management needs of Canadians for the purpose of improving health outcomes. These directions apply to all pharmacists and other pharmacy team members working in all settings.

Summary theme 1: Organizational change

The profession of pharmacy needs to undertake substantial organizational change within the pharmacy setting. In this transformation, specific policies and practices to support proactive, comprehensive, quality care for individual patients will be applied all together for every patient and will be in place in every pharmacy and within organizations that support pharmacies. The ongoing goals, risks and needs of a patient will be explicitly identified and well understood by the pharmacist and form the basis of care provided by the pharmacist. Preventative care will be planned and organized for an individual patient or groups of patients as part of continuous, routine care. Delivery of a professional pharmacy service to an individual will be considered as a tool or component of a more holistic care plan. Linking multiple service providers as a means to deliver more comprehensive care will be commonplace. Monitoring and follow-up will be part of routine care. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will practise to their full scopes and work as a team to provide clinical care. Dispensing medication may not be a significant component of on-site pharmacy services. As dispensing and front-store products are increasingly managed by off-site storage and delivery, a pharmacy will repurpose physical layout and optimize workflow processes to support patient assessment and communication, including the use of eHealth technology, private rooms and interprofessional and intraprofessional teamwork. Documentation of any encounter in the clinical record will be considered essential so as to ensure that complete clinical information will be available for the next encounter. Electronic pharmacy records will be arranged to support comprehensive and longitudinal clinical care that will also incorporate or link with dispensing and service delivery records, electronic records from other organizations (e.g., primary care or hospitals) and electronic software applications (apps). There will be an increase in use of analytics and artificial (machine) intelligence to streamline and improve drug distribution and clinical services, including removing uncomplicated work processes from the pharmacy. Quality improvement (including patient safety) and population-based approaches to care delivery will be part of everyday practice. Patients who are more vulnerable, including those on high-risk medications with multimorbidity, and those who have lower socioeconomic status or low health literacy will be a focus of increased attention. Most important, the transformation will occur in all pharmacy settings.

The achievement of organizational change transformation is not dependent on first attaining new scopes of practice. Rather, this transformation can be accomplished by leveraging existing opportunities to enhance how the profession of pharmacy applies the current scope of practice, recognizing that these vary across Canada. There is a great need to ensure that each patient can be served with the optimal scope available at this time. Subsequently, each jurisdiction will consider how further enhanced scopes, such as initiation of any prescription, making recommendations for common ailments or widening the set of approved injections given by pharmacists (or pharmacy technicians), will offer additional benefits for patient care.

Summary theme 2: Better external relationships

The profession of pharmacy needs to transform how it connects to patients where they live and with other health care organizations, including how connections occur among community, hospital, primary care, other health care professionals, long-term care and home settings. In this transformation, a pharmacist will have a relationship with his or her patient that strengthens a pharmacist’s understanding of the spectrum of the patient’s care. Pharmacists will develop and implement care plans together with other members of the health care team. Pharmacists will easily share clinical records with other health care providers or organizations, including those in a Patient’s Medical Home and with patients themselves. Patients will provide the pharmacist with information on their health through regular electronic (including health records or apps at home) or manual information exchange. Pharmacists will have access to and interpret clinical information from other locations (e.g., community, hospital, home), including laboratory and diagnostic test results. Analytics will be applied to patient information that alert both pharmacists and patients about drug therapy problems and focus efforts on situations where pharmacists can have the most impact. Pharmacists will be able to easily triage or refer patients to other health and community organizations or activities and have a system in place to receive referrals from others inside or outside an organization. Pharmacy team members will initiate and participate in local education and health policy initiatives together with other health care team members. Pharmacy initiatives will be integrated into interprofessional health care pathways for the management of chronic disease or hospital admission/posthospital discharge care. Pharmacists will be active in local health policy decision-making. Pharmacists from different organizations or sectors will have established ways of collaborating in the best interest of the patient (i.e., intraprofessional collaboration).

Conclusions

Transformational change is needed by the profession of pharmacy in all practice settings to tackle the medication management needs of Canadians for the purpose of improving health outcomes. This is a tall order. If the profession of pharmacy does not make these changes, we risk becoming irrelevant. Substantial cultural, professional, technological, health care system and business shifts are required. Alignment of multiple stakeholders to focus on patient and population health outcomes is needed to stimulate transformation. Determining how patients can benefit from the expertise and services provided by pharmacists as care providers within an integrated care system presents an important and exciting opportunity for the pharmacy profession.

Substantial evidence gaps exist to inform the profession of pharmacy about the most effective ways to meet today’s challenges. Evidence gaps include the need for data on implementation of new medication management approaches from the perspective of patients, pharmacists, other care providers and health-related organizations. Evidence gaps also include the need for data on the health outcomes and health care resource utilization changes due to implementation of new pharmacy-led medication management approaches. New evidence will improve understanding of how a particular activity, service or approach to care can better meet patient and health care system needs or provide associated benefits. In turn, this will help the profession of pharmacy encourage organizational change within the pharmacy setting and in how it connects to patients where they live and with other health care organizations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 815717_App_1_online_supp for Pharmacy in the 21st century: Enhancing the impact of the profession of pharmacy on people’s lives in the context of health care trends, evidence and policies by Lisa Dolovich, Zubin Austin, Feng Chang, Barbara Farrell, Kelly Grindrod, Sherilyn Houle, Lisa McCarthy, Lori MacCallum and Beth Sproule in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, 815717_App_2_online_supp for Pharmacy in the 21st century: Enhancing the impact of the profession of pharmacy on people’s lives in the context of health care trends, evidence and policies by Lisa Dolovich, Zubin Austin, Feng Chang, Barbara Farrell, Kelly Grindrod, Sherilyn Houle, Lisa McCarthy, Lori MacCallum and Beth Sproule in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Anita Di Loreto and Natalie Bozinovski for administrative support. Thank you to Annalise Mathers, Manmeet Khaira, and Xioa Li for comments and copy-edits. Thank you to Susan James, Anne Resnick, and Nancy Lum-Wilson for thoughtful discussion, input and edits.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:All authors approved the final version of the article. Each author generated an overview for one specific topic, participated in group discussion, reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:Ontario College of Pharmacists and Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network. This paper is a condensed and adapted version of a White Paper prepared by the Ontario Pharmacy Evidence Network (OPEN) at the request of the Ontario College of Pharmacists (OCP) for the purpose of stimulating a discussion within the profession. The White Paper was presented to OCP Council on June 11, 2018. The authors received no personal financial support for the research, authorship and /or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs:Lisa Dolovich  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0061-6783

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0061-6783

Sherilyn Houle  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5084-4357

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5084-4357

Lisa McCarthy  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-1077

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-1077

References

- 1. Ontario College of Pharmacists. Council. Available: www.ocpinfo.com/about/council/council/ (accessed July 11, 2018).

- 2. Bayoumi I, Dolovich L, Hutchison B, et al. Medication-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among older adults. Can Fam Physician 2014;60(4):e217-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tache SV, Sonnichsen A, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence of adverse drug events in ambulatory care: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 2011;45(7-8):977-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Winterstein AG, Sauer BC, Hepler CD, et al. Preventable drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36(7-8):1238-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statistics Canada. The Canadian population in 2011: age and sex. Available: www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-311-x/98-311-x2011001-eng.cfm (accessed July 11, 2018).

- 6. Statistics Canada. Immigrant status and period of immigration. Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016186. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/98-400-X2016186 (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 7. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Drug abuse among seniors on public drug programs in Canada, 2012. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hakkarainen KM, Andersson Sundell K, Petzold M, et al. Prevalence and perceived preventability of self-reported adverse drug events—a population-based survey of 7099 adults. PLoS One 2013;8(9):e73166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hohl CM, Nosyk B, Kuramoto L, et al. Outcomes of emergency department patients presenting with adverse drug events. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58(3):270-79.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu C, Bell CM, Wodchis WP. Incidence and economic burden of adverse drug reactions among elderly patients in Ontario emergency departments a retrospective study. Drug Saf 2012;35(9):769-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Prescribed drug spending in Canada, 2017: a focus on public drug programs. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2017. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/pdex2017-report-en.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kehrer JP, James DE. The role of pharmacists and pharmacy education in point-of-care testing. Am J Pharm Educ 2016;80(8):129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Medical Association and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. National Physician Survey: 2014 survey results. Available: http://nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/surveys/2014-survey/survey-results-2/ (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 14. The Commonwealth Fund. International profiles of health care systems. Available: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2017/may/mossialos_intl_profiles_v5.pdf?la=en (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 15. Webster P. Growing use of integrated e-health systems. CMAJ News 2017. August 1 Available: http://cmajnews.com/2017/08/01/growing-use-of-integrated-e-health-systems-cmaj-109-5455/ (accessed July 9, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Patients First: action plan for health care. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/ms/ecfa/healthy_change/docs/rep_patientsfirst.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 17. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Patients First: a proposal to strengthen patient-centered health care in Ontario. Discussion paper. December 17, 2015. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/news/bulletin/2015/docs/discussion_paper_20151217.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 18. Alberta Health Services. The Patient First Strategy. Available: www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/pf/first/if-pf-1-pf-strategy.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 19. British Columbia Ministry of Health. The British Columbia Patient-Centered Care Framework. 2015. Available: www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2015_a/pt-centred-care-framework.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 20. Government of Saskatchewan. Patient First review update: the journey so far and the path forward. 2015. Available: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/~/media/files/health/health%20and%20healthy%20living/health%20care%20provider%20resources/sask%20health%20initiatives/patient%20first/patient-first-update-2015.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 21. Current issues in mental health in Canada: the federal role in mental health. In brief. Publication No. 2013-76-E. Ottawa (ON): Library of Parliament; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Mental health strategy for Canada. Available: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/resources/mhcc-reports/mental-health-strategy-canada (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 23. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Open minds, healthy minds. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/mental_health2011/mentalhealth_rep2011.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 24. Michael H. Policy analytical capacity and evidence-based policy-making: lessons from Canada. Can Pub Admin 2009;52(2):153-75. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lomas J, Brown AD. Research and advice giving: a functional view of evidence-informed policy advice in a Canadian Ministry of Health. Milbank Q 2009;87(4):903-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ellen ME, Leon G, Bouchard G, et al. What supports do health system organizations have in place to facilitate evidence-informed decision-making? A qualitative study. Implement Sci 2013;8:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The College of Family Physicians of Canada. The patient’s medical home. Available: http://patientsmedicalhome.ca/ (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 28. Rosser WW, Colwill JM, Kasperski J, et al. Progress of Ontario’s Family Health Team model: a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 2011;9(2):165-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Breton M, Levesque JF, Pineault R, et al. Primary care reform: can Quebec’s family medicine group model benefit from the experience of Ontario’s Family Health Teams? Health Policy 2011;7(2):e122-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Zhang J, et al. Enrolment in primary care networks: impact on outcomes and processes of care for patients with diabetes. CMAJ 2012;184(2):E144-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saskatchewan Health Quality Council. We’re helping to improve health care in Saskatchewan. Available: https://www.hqc.sk.ca/ (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 32. Health Quality Ontario. Our mandate, vision and mission. Available: www.hqontario.ca/About-us/Our-Mandate-and-Our-People/Our-Mandate-Vision-and-Mission (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 33. Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006-2010. Pharmacotherapy 2014;34(8):771-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anderson SL, Marrs JC. A review of the role of the pharmacist in heart failure transition of care. Adv Ther 2018;35(3):311-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dixon DL, Dunn SP, Kelly MS, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led amiodarone monitoring services on improving adherence to amiodarone monitoring recommendations: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36(2):230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Entezari-Maleki T, Dousti S, Hamishehkar H, et al. A systematic review on comparing 2 common models for management of warfarin therapy; pharmacist-led service versus usual medical care. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56(1):24-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leache L, Aquerreta I, Aldaz A, et al. Evidence of clinical and economic impact of pharmacist interventions related to antimicrobials in the hospital setting. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37(5):799-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gallagher J, McCarthy S, Byrne S. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacist interventions on hospital inpatients: a systematic review of recent literature. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36(6):1101-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Manzoor BS, Cheng WH, Lee JC, et al. Quality of pharmacist-managed anticoagulation therapy in long-term ambulatory settings: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 2017;51(12):1122-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, et al. Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primary care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;83(6):913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McLean DL, McAlister FA, Johnson JA, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist and nurse care on improving blood pressure management in patients with diabetes mellitus: study of cardiovascular risk intervention by pharmacists-hypertension (SCRIP-HTN). Arch Intern Med 2008;168(21):2355-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, et al. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014;10(4):608-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(2):CD008986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: an overview of systematic reviews. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13(4):661-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McNab D, Bowie P, Ross A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27(4):308-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JAE. Pharmacy-led medication reconciliation programmes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016;41(2):128-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(10):CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Renaudin P, Boyer L, Esteve MA, et al. Do pharmacist-led medication reviews in hospitals help reduce hospital readmissions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82(6):1660-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert ML, Lund ML, et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(3):375-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hohl CM, Partovi N, Ghement I, et al. Impact of early in-hospital medication review by clinical pharmacists on health services utilization. PLoS One 2017;12(2):e0170495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Al Hamarneh YN, Charrois T, Lewanczuk R, et al. Pharmacist intervention for glycaemic control in the community (the RxING study). BMJ Open 2013;3:e003154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pousinho S, Morgado M, Falcao A, et al. Pharmacist interventions in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2016;22(5):493-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tsuyuki RT, Al Hamarneh YN, Jones CA, et al. The effectiveness of pharmacist interventions on cardiovascular risk: the multicenter randomized controlled RxEACH trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67(24):2846-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Villeneuve J, Genest J, Blais L, et al. A cluster randomized controlled Trial to Evaluate an Ambulatory primary care Management program for patients with dyslipidemia: the TEAM study. CMAJ 2010;182(5):447-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacy in Canada. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/pharmacists-in-canada/ (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 56. Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada—final report. 2002. Available: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf (accessed July 9, 2018).

- 57. Pharmacy Practice +. Community pharmacy trends and insights 2015. Toronto (ON): Rogers Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists’ expanded scope of practice in Canada. 2015. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/news-events/ExpandedScopeChart_June2015_EN.pdf (accessed July 27, 2017).

- 59. Dolovich L, Consiglio G, MacKeigan L, et al. Uptake of the MedsCheck annual medication review service in Ontario community pharmacies between 2007 and 2013. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2016;149(5):293-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kolhatkar A, Cheng L, Chan FK, et al. The impact of medication reviews by community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2016;56(5):513-20.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kwong J, Cadarette S, Schneider E, et al. Community pharmacies providing influenza vaccines in Ontario: a descriptive analysis using administrative data. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2015;148(4):S12. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Marcellus M, Pojskic N. Ontario pharmacists’ perceptions of the Pharmaceutical Opinion Program. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2015;148(3):129-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dolovich L, Consiglio GP, Abrahamyan L, et al. A comparison between initial and well-established implementation periods of the Ontario MedsCheck annual pharmacy medication review service. 2015. Annual CAHSPR Conference, Montreal, QC. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pechlivanoglou P, Abrahamyan L, MacKeigan L, et al. Factors affecting the delivery of community pharmacist-led medication reviews: evidence from the MedsCheck annual service in Ontario. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16(1):666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. MacCallum L, Consiglio G, MacKeigan L, et al. Uptake of Community Pharmacist-Delivered MedsCheck Diabetes Medication Review Service in Ontario between 2010 and 2014. Can J Diabetes 2017;41(3):253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sutherland G, Dinh T. The pharmacist in your neighbourhood: economic footprint of Canada’s community pharmacy sector. Ottawa (ON): The Conference Board of Canada; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, 815717_App_1_online_supp for Pharmacy in the 21st century: Enhancing the impact of the profession of pharmacy on people’s lives in the context of health care trends, evidence and policies by Lisa Dolovich, Zubin Austin, Feng Chang, Barbara Farrell, Kelly Grindrod, Sherilyn Houle, Lisa McCarthy, Lori MacCallum and Beth Sproule in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, 815717_App_2_online_supp for Pharmacy in the 21st century: Enhancing the impact of the profession of pharmacy on people’s lives in the context of health care trends, evidence and policies by Lisa Dolovich, Zubin Austin, Feng Chang, Barbara Farrell, Kelly Grindrod, Sherilyn Houle, Lisa McCarthy, Lori MacCallum and Beth Sproule in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada