Abstract

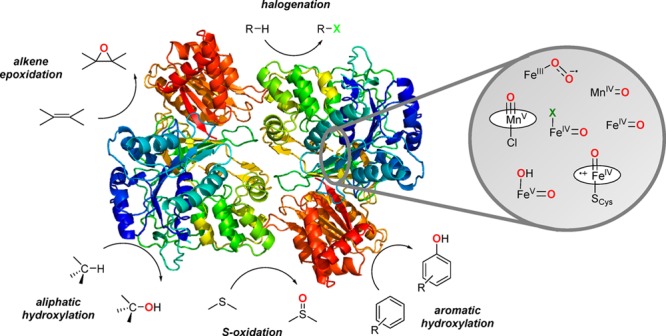

Utilization of O2 as an abundant and environmentally benign oxidant is of great interest in the design of bioinspired synthetic catalytic oxidation systems. Metalloenzymes activate O2 by employing earth-abundant metals and exhibit diverse reactivities in oxidation reactions, including epoxidation of olefins, functionalization of alkane C–H bonds, arene hydroxylation, and syn-dihydroxylation of arenes. Metal–oxo species are proposed as reactive intermediates in these reactions. A number of biomimetic metal–oxo complexes have been synthesized in recent years by activating O2 or using artificial oxidants at iron and manganese centers supported on heme or nonheme-type ligand environments. Detailed reactivity studies together with spectroscopy and theory have helped us understand how the reactivities of these metal–oxygen intermediates are controlled by the electronic and steric properties of the metal centers. These studies have provided important insights into biological reactions, which have contributed to the design of biologically inspired oxidation catalysts containing earth-abundant metals like iron and manganese. In this Outlook article, we survey a few examples of these advances with particular emphasis in each case on the interplay of catalyst design and our understanding of metalloenzyme structure and function.

Short abstract

This Outlook summarizes the recent advances in bioinspired oxidation catalysis with particular emphasis on the interplay of catalyst design and knowledge of metalloenzyme structure and function.

1. Introduction

Dioxygen (O2) is kinetically quite stable toward reaction at room temperature because of its triplet ground state, which makes its two-electron reaction with closed shell reaction partners like typical organic compounds spin-forbidden.1−4 The single electron reduction of triplet oxygen (3O2) to the superoxide anion is also unfavorable by 7.8 kcal mol–1.5 Nevertheless, the overall four-electron reductive activation of O2 is thermodynamically favorable with a redox potential of 0.815 V vs NHE in water at pH 7 and 25 °C.5 Nature is able to harness the strong oxidizing capability of O2 by overcoming the spin state barrier by activating 3O2 at transition metal ions, which also possess open-shell spin ground states.6,7 These metal ions help to initiate the one-electron reduction of O2 by metal coordination and also act as multielectron reductants to access thermodynamically more favorable two-electron or even four-electron reduction pathways.8−11 First-row transition metal ions, such as Fe and Cu, are often employed by metalloenzymes for the reductive activation of O2 to carry out a variety of important biological processes.1−3,6,7

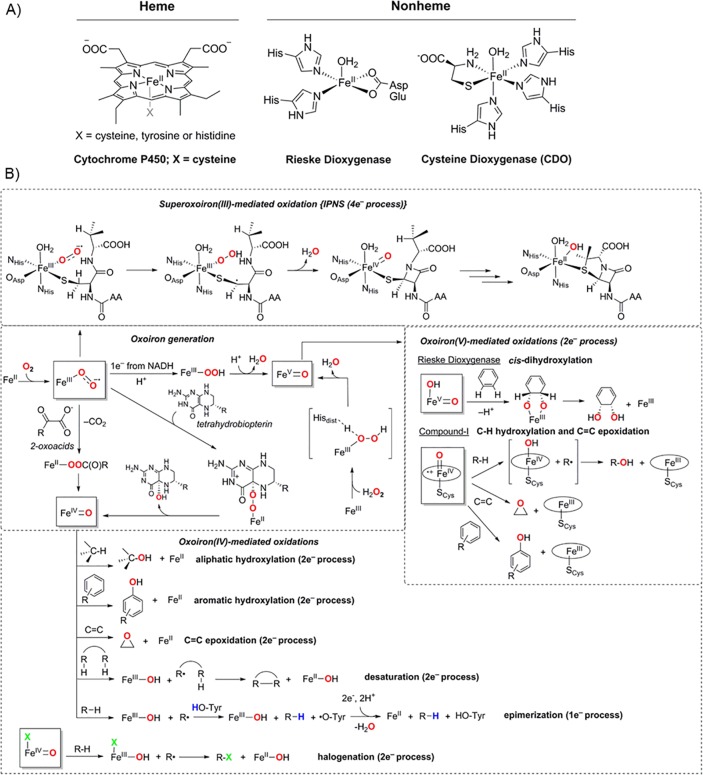

The ability of iron to access multiple redox states, as well as its bioavailability, makes it one of the most common transition metals used for biological O2-activation.1−3,12−14 Further, there are a number of open-shell spin states available in the different common oxidation states of iron, with high-spin Fe(II) being the most relevant with regard to the binding and activation of O2. The heme-containing peroxidases, oxygenases, and catalases comprise mononuclear iron protoporphyrin IX active sites coordinated to either a cysteine, tyrosine, or histidine residue, respectively (Figure 1A; Heme).15 In nonheme iron enzymes, in contrast, a common structural motif utilized for dioxygen activation is the facial orientation of iron with two histidine ligands and one carboxylate ligand, namely, a 2-His/1-Asp (or 1-Glu) ligand environment (Figure 1A; Nonheme, Rieske Dioxygenase).16−19 A 3-His ligand coordination environment has also been observed in a few cases, such as in a number of sulfur-activating nonheme iron dioxygenases (Figure 1A; nonheme, CDO).16−19 Very often enzymatic activation of dioxygen occurs in the Fe(II) state, leading to a variety of two-electron oxidation processes; a cosubstrate then provides the remaining two electrons necessary for the four-electron reduction of dioxygen (Figure 1B).16−19 In many cases, 2-oxoacids or tetrahydrobiopterin are used as cosubstrates that deliver two electrons simultaneously to the active site to form peroxoiron(II) and oxoiron(IV) species in the proposed reaction mechanism (Figure 1B; Oxoiron generation).16−19 Enzymes, such as cytochromes P450 (P450) or Rieske dioxygenases, in contrast, employ NADH as the electron donor to form hydroperoxoiron(III) and formally oxoiron(V) species; all the redox equivalents of the formal oxoiron(V) species are stored either at the metal center as an (OH)FeV=O intermediate in Rieske dioxygenase or delocalized over the ligand as an oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical ion (compound I (Cpd-I) intermediate) in P450.13,16−19 A second subset of nonheme iron enzymes also initiates four-electron oxidation of substrates by a single equivalent of dioxygen in the absence of any reducing cosubstrates (Figure 1B; isopenicillin-N synthase (IPNS)).20 This alternative mechanism for iron-mediated dioxygen reduction and C–H activation necessitates an superoxoiron(III) intermediate to initiate catalysis, which may involve a subsequent oxoiron intermediate in the second oxidation step.18

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of mononuclear heme and nonheme active sites for dioxygen activation. (B) Mechanisms of dioxygen activation for one-, two-, and four-electron substrate oxidation processes.

Synthetic biomimetic model complexes have the potential to aid in the understanding of these biological processes. A number of iron model complexes binding oxygen atom(s) have been isolated in recent years;1,13,18,21−33 detailed reactivity studies together with spectroscopy and theory have helped us understand how the electronic and geometric properties of the iron centers modulate their reactivity. These studies have provided important insights into biological pathways, which have led to a new understanding of the fundamental reaction steps and reactive intermediates relevant to metalloenzymes that incorporate inexpensive and readily available transition metal centers in their active sites, as well as to practical applications. This has eventually contributed to the recent advances in the design of biologically inspired oxidation catalysts containing earth-abundant metals such as iron and manganese.34−36 In this Outlook article, we survey examples of these advances providing particular emphasis in each case on the interplay of catalyst design and our understanding of metalloenzyme structure and function.

2. Heme Systems

Biological Intermediates

Cpd-I is the main intermediate responsible for the diverse oxidative reactivities of most heme enzymes.1,6,7,13,15,37−40 Efforts were mainly dedicated toward the characterization of the Cpd-I intermediate of P450, which proved to be very challenging because of its highly reactive nature. The Cpd-I of other heme-containing enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP), catalase, and chloroperoxidase (CPO) are much more stable and have been well characterized and unambiguously assigned as an oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical species;15,41−43 however, they did not show any reactivity toward unactivated hydrocarbons. The lack of direct spectroscopic and kinetic characterization of P450 Cpd-I led to the proposition of oxoiron(V) and hydroperoxoiron(III) species as alternative oxidants in P450 mediated oxidation reactions.44−46 Recently, Green and co-workers were eventually successful in stabilizing the Cpd-I of CYP119 by using rapid freeze-quench techniques and established its catalytic competence by demonstrating its ability to oxidize unactivated hydrocarbons with an apparent second-order rate constant of kapp = 1.1 × 107 M–1 s–1.39 A large KIE of 12.5 was determined for the hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT) reaction, whose magnitude supports a mechanism in which Cpd-I abstracts a hydrogen atom from substrates, forming hydroxoiron(IV) (e.g., compound-II (Cpd-II)) that rapidly combines with a substrate radical to yield a hydroxylated product; this is called the oxygen-rebound mechanism proposed by Groves and co-workers.13,47−49 Furthermore, the electronic structure of the CYP119 Cpd-I intermediate was confirmed to be an oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical based on the near-zero isomer-shift in the Mössbauer spectrum, the doublet electronic ground state in the electron paramagnetic resonance spectrum, and the weekend and blue-shifted Soret band in the UV–vis, as well as a long-wavelength absorbance in the visible near 700 nm.39 Groves and co-workers recently stabilized a second Cpd-I intermediate for the extracellular heme-thiolate aromatic peroxygenase (APO), which like CYP119 Cpd-I also showed a high reactivity for the C–H bond hydroxylation up to 100 kcal mol–1 with the rates of 10–105 M–1 s–1.50 The high reactivity of the Cpd-Is of the CYP119 and APO enzymes has been attributed to their highly basic Cpd-IIs as evident from the experimentally determined large pKa’s of 12.0 and 10.0, respectively.51,52 Notably, a more basic ferryl in Cpd-II translates into a stronger FeIVO–H bond according to the Bordwell’s equation,51−53 thus increasing the driving force for HAT from the substrate. Accordingly, Green and co-workers proposed that the role of the cysteine thiolate in P450 catalysis is to make P450 Cpd-II more basic than a typical metal-oxo species by pushing electron density onto the ferryl oxygen.51 This would allow for the cleavage of strong C–H bonds at biologically viable reduction potentials without damaging the protein scaffold.

Synthetic Model Complexes

The first high-valent oxoiron porphyrin complex [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)Cl] (Figure 2, Synthetic model systems, Heme) was synthesized in 1981 by Groves and co-workers via oxidation of [(TMP)FeIII(Cl)] (TMP = meso-tetramesitylporphinato dianion) with meta-chloroperbenzoic acid in a dichloromethane-methanol mixture at −78 °C.29 The electronic structure was best described in terms of an overall quartet (St = 3/2) ground state, arising from a ferromagnetic coupling of the S = 1 iron(IV) center with a porphyrin π-cation radical (S = 1/2). This is in contrast to the St = 1/2 ground state determined for the P450 Cpd-I intermediate,39 where an antiferromagnetic interaction between the iron(IV) and the porphyrin π-cation radical center was predominant. Successful generation of a number of oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-radicals bearing electron-rich and -deficient porphyrins has been achieved subsequently.54−58 Interestingly, a ground St = 3/2 state has been determined for all these intermediates; however, the extent of the ferromagnetic interaction between the iron(IV) and porphyrin π-cation radical center is strongly dependent on the meso and pyrole-β positions of the porphyrin ligand.13 These experimental findings suggest a facile interconversion between the doublet and the quartet spin states of Cpd-I.

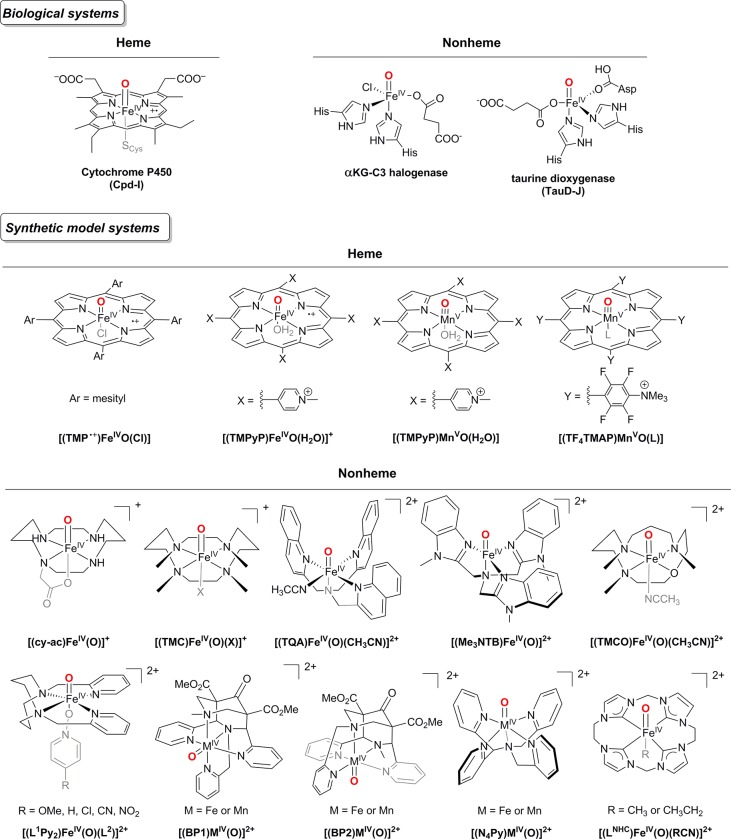

Figure 2.

Examples of heme and nonheme intermediates containing oxoiron and oxomanganese cores in biological and synthetic model systems.

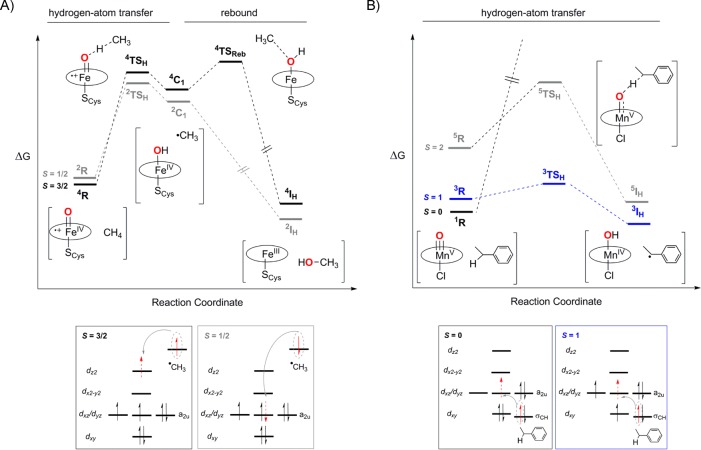

The availability of different spin states in the oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical cores may lead to spin crossover along the reaction coordinate from reactants to products during Cpd-I mediated oxidation reactions. This concept was first proposed by Shaik, Schröder, and Schwarz in the C–H hydroxylation by Cpd-I and termed “two-state reactivity (TSR)” or “multistate reactivity (MSR)”.59−61 For example, density functional theory (DFT) analysis of methane hydroxylation by an oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical intermediate investigated the possibility of the involvement of both the S = 3/2 and S = 1/2 states in the HAT and oxygen-rebound steps (Figure 3A). While both the high-spin (HS) and low-spin (LS) pathways showed similar energy barriers for HAT, the HS pathway exhibited a larger barrier for the rebound step. In the HS state, the unpaired electron of the radical goes into a higher energy 3dz2 orbital of the S = 1 FeIV–OH core of Cpd-II, whereas in the LS state the electron transfers into a lower energy singly occupied dxz (or dyz) orbital.

Figure 3.

(A) Energy profile and reaction coordinate for the methane hydroxylation reaction by an oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radical species. Reprinted with permission from ref (58). Copyright 2017 Springer Nature. (B) Energy profile and reaction coordinate for the C–H activation by an oxomanganese(V) porphyrin complex. Reprinted with permission from ref (13). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

The C–H bond activation mediated by oxomanganese(V) porphyrin represents another example of potential TSR in metalloporphyrin-mediated reactions (Figure 3B).62 DFT calculations predicted a much higher barrier for the HAT step in the singlet state (S = 0) as compared to that in the triplet (S = 1) or quintet (S = 2) state; this is the result of the exchange enhanced reactivity at the S = 2 or S = 1 surface. Since a singlet ground state has been determined for all oxomanganese(V) porphyrins characterized to date,63 a spin crossing to the triplet/quintet energy surface is expected during the C–H activation reaction. Consistent with these predictions, electron-withdrawing meso-substituents on the porphyrin dramatically decreased the reactivity of oxomanganese(V) porphyrins because of the stabilization of the S = 0 ground state.64 In contrast, for oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radicals, a different reactivity trend was observed; introduction of electron-withdrawing meso-substituents was shown to increase the reduction potential of Cpd-I greatly, thereby increasing the thermodynamic driving force of HAT.65 For example, a highly electron-withdrawing Cpd-I intermediate [(TMPyP)FeIV(O)(H2O)]+ (TMPyP = 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-methyl-4-pyridinium)porphinato dianion) (Figure 2, Synthetic model systems, Heme) was prepared and shown to exhibit rate constants comparable to that of P450 for benzylic C–H hydroxylation reactions.66

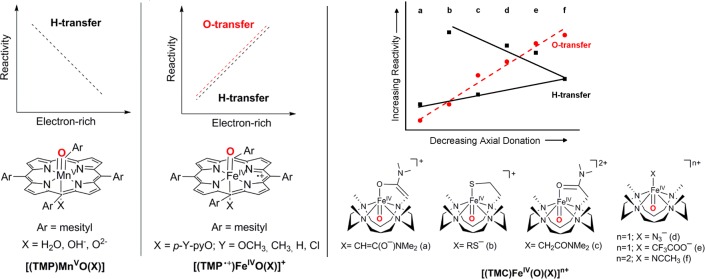

A contrasting reactivity pattern has also been observed for the axial ligand effects on the reactivity of oxomanganese(V) porphyrins and oxoiron(IV) porphyrin π-cation radicals (Figure 4; left and middle).62−64,67,68 The HAT activity of a series of axially substituted [(TMP)MnV(O)(X)] (X = H2O, OH–, and O2–) complexes is found to increase in the order of H2O > OH– > O2–; this trend of decreasing reactivity with increasing electron-donation is shown to highlight the increasing energy gaps between the unreactive singlet ground state and the reactive triplet and quintet excited states on going from H2O to OH– and to O2–.68 In contrast, a recent study by Nam, Shaik, and co-workers demonstrated that the rates of both HAT and oxygen atom transfer (OAT) reactions of a series of [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)(X)]+ (X = p-Y-pyO; Y = OCH3, CH3, H, and Cl) and [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)(X)] (X = CF3SO3–, Cl–, AcO–, and OH–) increase with increasing electron-donation from the axial ligand (Figure 4; middle).67 It is suggested that increasing axial donation strengthens the Fe–O–H bond, thereby increasing HAT activity. In addition, that also weakens the Fe=O bond, thereby enhancing the oxo-transfer reactions. However, in a subsequent study, inconsistent with the previous suggestion, Fuji and co-workers showed that the reaction rates of a series of axially substituted Cpd-I model complexes [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)(X)] with X = nitrate (NO3), trifluoroacetate (TFA), acetate (Ac), chloride (Cl), fluoride (F), benzoate (Bz), and hydrocinnamate (Hc) did not correlate with the Fe=O vibration or the redox potential of the oxoiron(IV) porphyrin complexes.65,69 Surprisingly, however, a direct correlation was observed between the reaction rate constants of [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)(X)] and the redox potentials of FeII/FeIII in [(TMP)FeIII(X)] complexes, which are the final heme species after the reaction. On the basis of these results, it was suggested that the axial ligand controls the reactivity of Cpd-I by modulating the thermodynamic stability of the iron(III) porphyrin species, but not by that of Cpd-I itself. Stronger electron-donation from the axial ligand should also increase the stability of the [(TMP)FeIV(OH)(X)] species formed after the HAT step; this should decelerate the rebound step, which would facilitate the escaping of substrate radicals from the radical cage. Indeed, in the case of a manganese porphyrin, recent investigation of the rebound step in the hydroxylation of deuterated ethylbenzene has displayed more stereochemical inversion at the benzylic hydroxylation site with increasing axial donation to the manganese center.70

Figure 4.

Axial ligand effects on the O-transfer and H-transfer reactions by [(TMP)MnV(O)(X)], [(TMP+•)FeIV(O)(X)]+, and [(TMC)FeIV(O)(X)]n+. Reprinted with permission from refs (31 and 67). Copyright 2016 and 2009 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH, respectively.

Biomimetic Catalysis

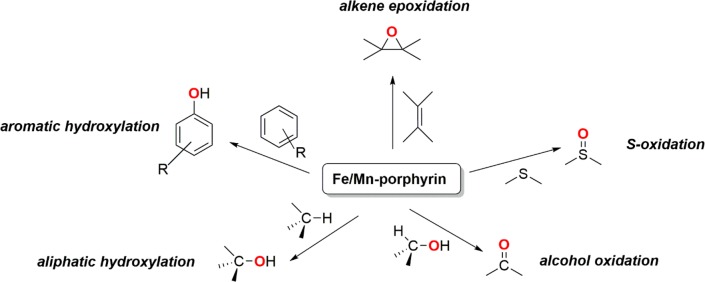

In 1979, Groves and co-workers reported the first oxidation system using [(TPP)FeIII(Cl)] (TPP = meso-tetraphenylporphinato dianion) as a catalyst for C–H hydroxylation and alkene epoxidation reactions.71 Since then, a variety of modifications have been incorporated into the bioinspired porphyrin backbone, in an effort to understand the factors that control the catalytic efficiency.54,56,57,72−74 In C–H oxidation reactions, the simplest metalloporphyrins without substituents at the meso-positions have been found to be extremely unstable against the oxidative degradation that leads to the hydroxylation at the meso-position; this eventually leads to the inefficiency of catalytic activity.75 It has been subsequently demonstrated that introduction of phenyl or related groups at the meso-positions is a good strategy, which provides efficient catalytic oxidations by protecting these sites. Furthermore, based on the observed higher reactivity of the Cpd-I intermediates in the presence of the electron-withdrawing meso-substituents on the porphyrin, catalytic oxidation reactions were also tried in the presence of meso-phenyl substituted metalloporphyrins bearing electron-withdrawing groups, such as [(TPFPP)FeIII]+ (TPFPP = meso-tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)porphinato dianion) and [(TDCPP)FeIII]+ (TDCPP = meso-tetrakis(2,6-dichlorophenyl)porphinato dianion).58,74 Some of these second generation porphyrin catalysts involving electron-withdrawing meso-substituents have shown high reactivities in oxidation for scalable synthetic transformations of great interest for industry and academics (Figure 5).54,56 They cover a wide variety of catalytic oxidation reactions, such as epoxidation, sulfoxidation, alcohol oxidation, arene hydroxylation, and aliphatic C–H functionalization reactions. The oxygen donors typically employed in these reactions include sodium hypochlorite, iodosylbenzene (PhIO), alkyl hydroperoxides, hydrogen peroxide, and dioxygen. Among them, dioxygen is undoubtedly the most attractive oxidant; however, additional two-electrons and two-protons are required for the reduction of the second oxygen atom of dioxygen to water in the stoichiometric monooxygenase-mediated oxygenation reactions. Accordingly, the use of additional coreductants is necessary in oxidation reactions catalyzed by metalloporphyrins and dioxygen. These coreductants can be porphyrin itself,76 as has been demonstrated in a few metalloporphyrin-catalyzed epoxidation and C–H hydroxylation reactions, where the presence of external reductants is not a prerequisite for achieving catalysis.

Figure 5.

Oxidation reactions catalyzed by heme Fe/Mn models.

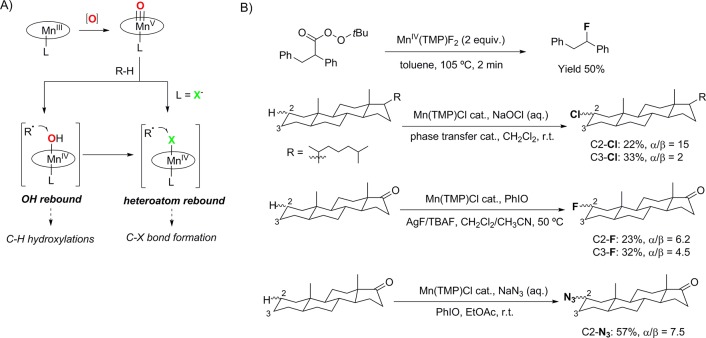

The importance of a systematic mechanistic study in the design of bioinspired catalysis is well represented in the development of aliphatic C–H halogenation or aziridination reactions catalyzed by manganese porphyrin complexes (Figure 6).13,35,70,77,78 Notably, all these reactions share common mechanistic features; they are all initiated by HAT via oxomanganese(V) intermediates, leading to the formation of hydroxomanganese(IV) and alkyl radicals (Figure 6A).35,77 As noted above, in the presence of strong anionic axial ligands such as F–, Cl–, and N3–, the oxygen-rebound can be suppressed, thus preventing the hydroxylation step.35,77 In the absence of an oxygen-rebound, the alkyl radical is trapped by the MnIV–X (X = Cl–, F–, and N3–) bonds, leading to the formation of C–Cl, C–F, or C–N3 products with high stereo- and regioselectivity (Figure 6B). The relative rates of the OH- vs X-rebound is crucial for the success of the nonoxygenation reactivity; for example, changing to iron porphyrins, which are known to perform very fast OH-rebound, suppress the nonoxygenation reactivity, thereby yielding mainly hydroxylation products.70

Figure 6.

(A) Concept of manganese-catalyzed C–H hydroxylation and halogenation reactions via an oxygen-rebound or X-rebound mechanism. (B) Mn-catalyzed C–H halogenation and aziridination reactions.

3. Nonheme Systems

Biological Intermediates

Taurine α-KG dioxygenase (TauD) is the first mononuclear nonheme iron enzyme showing the formation of an oxoiron(IV) intermediate (TauD-J) as an active oxidizing species, which has been characterized by various spectroscopic techniques.79,80 For example, Mössbauer characterization of a rapid-freeze-quenched sample of TauD-J generated in the reaction of O2 with TauD-α-KG-taurine complex revealed a high-spin (S = 2) FeIV center with an isomer shift (δ) of 0.30 mm s–1, quadrupole splitting of −0.90 mm s–1 and a trend of three large negative A (Ax, Ay, Az) tensors of −18.4 T, −17.6 T, and −31 T, respectively.80 Notably, the Mössbauer characterization of the Cpd-I intermediate in P450,39 in contrast, revealed a trend of two large and one small negative A (Ax, Ay, Az) tensors of −20 T, −23 T, and −3 T, respectively, which are characteristic of a low-spin (S = 1) FeIV center. The presence of a terminal Fe=O group in TauD-J was subsequently proved by the identification of an 18O-sensitive vibration at 821 cm–1 in the resonance Raman spectrum and the presence of a short Fe–O distance of 1.62 Å in EXAFS studies.81,82 Related FeIV=O intermediates,79,83 with Mössbauer parameters comparable to TauD-J, were subsequently detected in the catalytic cycles of other α-KG-dependent enzymes (prolyl-4-hydroxylase, halogenases (cytochrome c3 halogenases with chlorine or bromine and SyrB2 halogenase), desaturases (4′-methoxyviridicatin synthase), and epimerases (carbapenem synthase)) and pterin-dependent hydroxylases (tyrosine (TyrH) and phenylalanine (PheH) hydroxylases). For all the α-KG-dependent enzymes, large kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) of >50 were determined for the decay of the FeIV=O intermediates in the presence of deuterated substrates, which confirmed the participation of the oxoiron(IV) intermediates in HAT reactions (Figure 1B).84 The HAT step is then followed by a rapid oxygen-rebound in hydroxylases, a formation of a carbon–halogen bond in halogenases (containing a halide ligand adjacent to the hydroxide on the iron center), or a second HAT step in desaturases leading to two-electron oxidation of the substrates. For the redox-neutral epimerization reaction, however, the FeIV=O intermediate is found to be responsible for the one-electron oxidation of the substrate, which is necessary to initiate the epimerization process.

The spectroscopically trapped FeIV=O intermediates of the pterin-dependent hydroxylases,85−87 such as PheH and TyrH, are responsible for introducing a hydroxyl group at a specific position on the aromatic ring of the different amino acids. An electrophilic attack of the FeIV=O intermediates to the aromatic ring is proposed, which is supported by the observation of an inverse KIE and an NIH-shift during the hydroxylation of site-specifically deuterated aromatic substrates by PheH and TrypH.85 In addition to the aromatic hydroxylation, the pterin-dependent hydroxylases can also perform hydroxylation of aliphatic C–H bonds on non-native substrates; KIEs larger than nonclassical values have been determined in those cases again, confirming the participation of the FeIV=O intermediates in the HAT step.88 As evident from the above discussion, nonheme FeIV=O intermediates are primarily used in biology for HAT reactions. However, other relatively less common reactions, like epoxidation and endoperoxide formations,89,90 are also noted for nonheme FeIV=O intermediates; thus, nonheme oxygenases, like their heme counterparts, represent another example of nature’s tendency of generating similar active oxidants to perform different metabolically important transformations.

Synthetic Model Complexes

The diversified reactivity exhibited by the nonheme iron oxygenases (Figure 1B; Oxoiron(IV)-mediated oxidations) has inspired extensive efforts to mimic their high-valent oxoiron intermediates and emulate their reactivities. Wieghardt and co-workers reported the first generation of a mononuclear nonheme oxoiron(IV) complex by the ozonolysis of [(cy-ac)FeIII(CF3SO3)]+ (cy-ac = 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-1-acetate) in a solvent mixture of acetone/water at −80 °C (Figure 2; Nonheme).91 The metastable intermediate was characterized to be a low-spin (S = 1) iron(IV) species based on Mössbauer data (δ = 0.1 mm s–1 and ΔEQ = 1.39 mm s–1). The instability of the compound, however, prevented its further spectroscopic characterization. In a subsequent study, Münck, Nam, Que, and co-workers reported the first X-ray crystal structure of a mononuclear S = 1 oxoiron(IV) complex that was generated in the reaction of [(TMC)FeII(CH3CN)]2+ (TMC = 1,4,8,11-tetramethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane) and PhIO in CH3CN at −40 °C.28 Since then, a large number of nonheme oxoiron(IV) complexes supported on a wide range of tetradentate and pentadentate ligands have been synthesized.21,30−33,92 Unlike the enzymatic oxoiron(IV) cores with an S = 2 spin state, the majority of the synthesized FeIV=O cores possess an S = 1 ground state. Only a few biomimetic S = 2 oxoiron(IV) units are known that are all stabilized by enforcing a C3 symmetry about the iron(IV) center.30,32,33

The HAT, arene hydroxylation, and OAT reactivities of the nonheme oxoiron(IV) complexes have been investigated in significant detail by both theoretical and experimental methods.18,21,30−32,47,93−100 So far, all theoretical studies have predicted that the FeIV=O species are better oxidants on the quintet-state than on the corresponding triplet-state.93,96,101,102 Notably, the three most reactive oxoiron(IV) complexes in HAT and OAT reactions known to date either possess an S = 2 ground state (for example, in [(TQA)FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+, TQA = tris(2-quinolylmethyl)amine)103 or a highly reactive S = 2 excited state that lies in close proximity to the S = 1 ground state, such as in [(Me3NTB)FeIV(O)]2+ (Me3NTB = tris((N-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)methyl)amine)104 and [(TMCO)FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+ (TMCO = 4,8,12-trimethyl-1-oxa-4,8,12-triazacyclotetradecane)105 (Figure 2; Nonheme). All these complexes feature extremely weak equatorial donation from the ligand that reduces the energy separation between the dx2–y2 and dxy orbitals, thereby stabilizing the S = 2 state. While a single state HAT is suggested to take place in the [(TQA)FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+ complex, a TSR is predominant in the S = 1 [(Me3NTB)FeIV(O)]2+ and [(TMCO)FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+ complexes, which presumably tunnels efficiently into the low-lying S = 2 state, thereby revealing a low energy barrier for the HAT reactivity. Conversely, strong equatorial donation from the ligand will ensure stabilization of the less reactive S = 1 state; this explains the observed sluggish reactivity of the tetracarbene oxoiron(IV) complex reported by Meyer and co-workers (Figure 2; Nonheme).106−108 The higher reactivity of the S = 2 oxoiron(IV) core can also be extended to include arene hydroxylation reactions. Thus, although arene hydroxylation by a synthetic high-spin FeIV=O core has been reported,32 intermediate-spin FeIV=O complexes typically do not promote such reactions. Calculations suggest that, similar to HAT reactions, the reason for the low reactivity of triplet oxoiron(IV) is the steric interaction between the incoming aromatic substrate and the equatorial ligands, which blocks access to the key π* (dxz/yz) acceptor orbitals on the oxoiron(IV) unit.109−112 Consistent with this explanation, S = 1 oxoiron(IV) mediated arene hydroxylation reaction has only been recently demonstrated by properly orienting the aromatic substrate in the second coordination sphere, which enforces a linear approach of the substrate to the σ* (dz2) orbital, thereby ensuring limited steric interaction between the Fe=O core and the substrate.99,100,113

The nature of the axial donation also controls the HAT reactivity of the nonheme oxoiron(IV) complexes by controlling the energies of the iron 3dx2–y2 and 3dz2 orbitals.97,98,114,115 Increasing axial donation leads to the stabilization of the 3dx2–y2 orbital, which provides more access to the more reactive S = 2 state by lowering the energy gap between the ground S = 1 and excited S = 2 states; this will contribute to increased HAT reactivity. At the same time, the activation barrier for HAT reaction will increase at the S = 2 surface owing to destabilization of the 3dz2 orbital with increasing axial donation. The role of these two contrasting effects is nicely reflected in the reactivity pattern of a series of different axially substituted oxoiron(IV) complexes based on the TMC ligand. For the [(TMC)FeIV(O)(X)]n+ (X = NCCH3, CF3COO–, N3–, and RS–) complexes, the effect of decreasing triplet-quintet energy gap with increasing axial donation compensates for the increase in the classical activation barrier, thereby leading to an antielectrophilic trend of increasing HAT reaction rates with increasing axial donation (Figure 4; right).116 In contrast, a trend in the electrophilic reactivity is observed for the [(TMC)FeIV(O)(CH3CN)]2+, [(TMC)FeIV(O)(CH2CONMe2)]2+, and [(TMC)FeIV(O)(CH=C(O–)NMe2)]+ complexes (Figure 4; right), where the effect of destabilization of the dz2 orbital with increasing axial donation plays a dominant role in controlling the reactivity. In addition to tune the electron-donation properties of the axial and equatorial ligands, the reactivity of the nonheme oxoiron(IV) complexes can also be controlled by adding redox-innocent Lewis acid metal ions or proton.92,117−119 Notably, only the highly basic one-electron reduced oxoiron(III) species (and not the electrophilic oxoiron(IV) core) can interact strongly to the added metal ions or proton. This increases the thermodynamic driving force for reduction of the oxoiron(IV) core, resulting in a large positive shift of its one-electron reduction potential (Ered),92,117−119 thereby attributing to the enhancement of both the HAT and OAT reaction rates.

The situation is however different for the nonheme oxomanganese(IV and V) complexes,120−124 although a TSR concept is also applicable for rationalizing their HAT and OAT reactivities. Notably, known examples of mononuclear nonheme oxomanganese(IV) complexes (Figure 2) are all stabilized in an S = 3/2 ground state with an electronic configuration of dxy1dxz1dyz1dx2–y20dz20.125−129 However, the sterically less demanding σ pathway, involving electron transfer from substrate to the dz2 orbital, is energetically unfavorable for HAT reactions mediated by oxomanganese(IV) complexes, as the Mn 3dz2 orbital is destabilized relative to Fe 3dz2 owing to the lower effective nuclear charge of manganese. Correspondingly, MnIV=O mediated HAT reactions proceed predominantly along a π-pathway31 involving a higher activation barrier relative to the FeIV=O mediated HAT reactions. The predominance of the π reactivity also ensures that the HAT reactions mediated by MnIV=O species are controlled predominantly by steric effects. Accordingly, a contrasting reactivity pattern is observed in the HAT reactivity of the MnIV=O and FeIV=O complexes supported by the bispidine BP1 and BP2 ligands (see Figure 2 for [(BP1)MIV(O)]2+ and [(BP2)MIV(O)]2+).130 While the higher FeIV/FeIII reduction potential of the [(BP2)FeIV(O)]2+ complex relative to [(BP1)FeIV(O)]2+ results in faster HAT and OAT rates of the former, the corresponding [(BP2)MnIV(O)]2+ complex is a sluggish oxidant relative to [(BP1)MnIV(O)]2+ owing to the higher steric demand of BP2 relative to BP1. The higher steric demand of the MnIV=O mediated oxidation reactions is also reflected in the observed contrasting trends in their HAT and OAT reaction rates in the presence of Lewis- or Bronsted-acids.131 For example, the binding of Sc3+ ion to the [(N4Py)MnIV(O)]2+ complex (N4Py = N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-N-bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine) led to an enhancement in the OAT rates, but a deceleration of the HAT rates. While the large positive shift in the [Mn=O]IV/III reduction potential contributes to the increased OAT rates, the HAT reactions are presumably inhibited by sterics due to the binding of the Sc3+/H+ ion to the MnIV=O moiety.

Biomimetic Catalysis

As evident from the above discussion, reactivities of the nonheme enzymatic and synthetic oxoiron(IV) complexes are attributed to the S = 2 state. The prerequisite necessary for achieving biomimetic catalysis is therefore the generation of oxoiron(IV) complexes with readily available S = 2 state for the two-electron HAT or OAT reactions. Very recently, Long and co-workers demonstrated the achievement of a good compromise between reactivity and stability by employing metal–organic framework (MOF) to support highly reactive oxoiron moieties for catalytic C–H bond oxidation reactions under mild conditions.132 They showed that the magnesium-diluted high-spin iron(II) centers within Fe0.1Mg1.9(dobdc) (dobdc = 2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate) can activate N2O, most likely forming a transient high-spin oxoiron(IV) intermediate, which can undergo a rapid HAT from ethane, followed by a fast oxygen-rebound to yield ethanol with a low yield of 1% and a turnover of 1.5. DFT calculations have shown that a combination of four carboxylate and one aryloxide groups of the dobdc4– linker enforces a weak field ligand at the iron center, thereby stabilizing an S = 2 spin state of the transient oxoiron(IV) core. Furthermore, the porosity of the MOF structure provides easy access of the substrate to the oxoiron(IV) unit; a combination of these two factors ensures a rapid HAT reaction with ethane. In addition, the ethyl radical formed after the HAT step undergoes a preferential oxygen-rebound, leading to the hydroxylation product with a lower energy barrier relative to the alternative desaturation (via a second HAT step) or radical dissociation (leading to secondary products) steps involving higher energy barriers. However, the DFT calculated higher-energy barrier of the dissociation step relative to hydroxylation is not consistent with the experimentally observed high-yield formation of the one-electron oxidized Fe(III)–OH product which prematurely halts the catalytic cycle, thereby limiting the yield and turnover of ethanol product.132,133

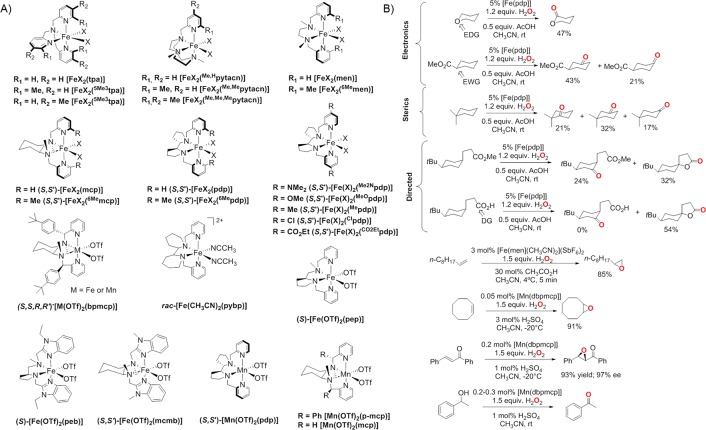

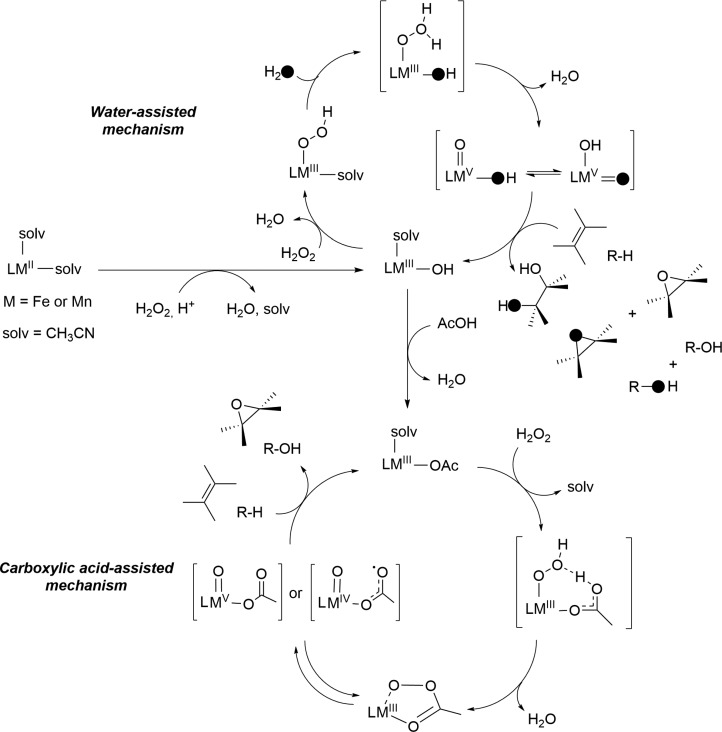

Controlled reductive cleavage of O2 to form highly oxidizing oxoiron(V) species has been proposed to take place in biology.134 For example, in Rieske dioxygenase, O2 binding at a ferrous center followed by one-electron reduction from a nearby Rieske Fe2S2 cluster results in the formation of an hydroperoxoiron(III) species, which is the last species detected before substrate oxidation occurs.135 It has been proposed that the Fe(III)-OOH species isomerizes toward an FeV(O)(OH) species, which exhibits diverse reactivities, including hydroxylation of aryl C–H bonds, epoxidation, and cis-dihydroxylation of arenes (Figure 1B).2,134 Direct cycling between the iron(III) and iron(V) states can also be achieved via a shunt mechanism by employing H2O2 as the oxidant; no reductase components are required in this case.136 This shunt pathway has been successfully used in catalytic C–H bond hydroxylation, epoxidation, and syn-dihydroxylation reactions by employing nonheme iron complexes (Figure 7).34,36,137−139 Further, in contrast to biology, where direct evidence of the oxoiron(V) intermediate is lacking,138 evidence for the involvement of oxoiron(V) species in chemical oxidation reactions has been accumulated recently.138,140−143 For example, iron(II) complexes with strong field tetradentate N-based ligands and possessing two cis-labile sites are competent catalysts, which are rapidly oxidized by H2O2 to produce mononuclear ferric species, which in the presence of water or alkane carboxylic acids (RCOOH) can split the O–O bond in a heterolytic manner to produce high-valent electrophilic FeV(O)(OH) or FeV(O)(OOCR) oxidants, respectively (Figure 8).34,36,142,144 A few FeV=O species have now been detected under catalytic turnover conditions and characterized by a variety of low-temperature MS, EPR, Mössbauer, and isotopic labeling studies.138,145,146 On the basis of detailed experimental and theoretical studies, these intermediates are shown to be strong oxidants and capable of regenerating the iron(III) resting state, thereby ensuring catalytic turnovers. In reactions with olefins, FeV(O)(OH) can lead to both stereoselective epoxidation and syn-dihydroxylation reactions, whereas FeV(O)(OOCR) is capable of performing only stereoselective epoxidation reactions.142 Furthermore, both the high-valent oxoiron(V) species are oxidants for C–H oxidation reactions, showing good selectivity toward the most electron rich C–H bonds of the substrates (Figure 7B; Electronics), as expected for highly electrophilic oxidizing species.140 The steric bulk of the catalyst also dictates the selectivity when there are no differences in the electronic factors, favoring oxidation at the least sterically encumbered positions (Figure 7B; Sterics). Alternatively, directing groups can be employed to override the steric and electronic factors, in order to achieve oxidation at a desired position; for example, selective hydroxylation in the γ-position with eventual formation of γ-lactones by employing carboxylic acid substrates (Figure 7B; Directed).139

Figure 7.

(A) Bioinspired Fe- and Mn-based nonheme catalysts. (B) Some examples showing the alkane hydroxylation, olefin epoxidation, and alcohol oxidation by nonheme iron and manganese catalysts and using H2O2 as an oxidant. Reprinted with permission from ref (140). Copyright 2017 Springer Nature.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanisms for the nonheme iron and manganese complex-catalyzed oxidation reactions, such as water-assisted mechanism and carboxylic acid-assisted mechanism. Reprinted with permission from ref (140). Copyright 2017 Springer Nature.

Bioinspired manganese complexes bearing nonheme ligands can also act as efficient catalysts in asymmetric epoxidation and hydroxylation reactions by employing H2O2 as an oxidant and carboxylic acids as an essential additive to improve product yields and stereo-, regio-, and enantioselectivities (Figure 7).124,147−152 Similar to the iron complexes, the availability of cis-binding sites is a prerequisite for the “carboxylic-acid assisted” heterolytic cleavage of the O–O bond in MnIII–OOH species, thereby leading to the generation of active MnV=O species.124,147−152 Notably, manganese complexes based on pentadentate nonheme ligands can also act as efficient epoxidation catalysts using PhIO as an oxidant. Second-sphere hydrogen-bonding interaction between the hydrogen atoms of the carboxylic acid and the oxo-group of the Mn(V)=O species presumably explains the formation of a highly reactive Mn(V)=O···H species responsible for the enantioselective epoxidation reaction.147

4. Conclusion

Metalloenzymes activate dioxygen by employing earth-abundant metals and exhibit diverse reactivities in oxidation reactions, including epoxidation of olefins, oxidation of alkane C–H bonds, and syn-dihydroxylation of arenes. Such reactions are carried out under ambient conditions with high efficiency and high stereospecificity. Research efforts from the last two decades have led to a detailed understanding of the mechanisms of the biological oxidation reactions. Dioxygen activation occurs predominantly at an iron(II) center, which is then followed by a controlled transfer of electrons (and protons) from a reductase component to generate high-valent metal-oxo species, which are responsible for the substrate oxidation reactions. In many cases, such proton and electron transfer events are precisely controlled by noncovalent interactions between the metal center of the active site and the protein derived secondary coordination sites bearing functional groups.153,154 Alternatively, an iron(III) resting state of the enzyme can react with H2O2 to form the metal-oxo species via a shunt pathway without the requirement of any reductase component.

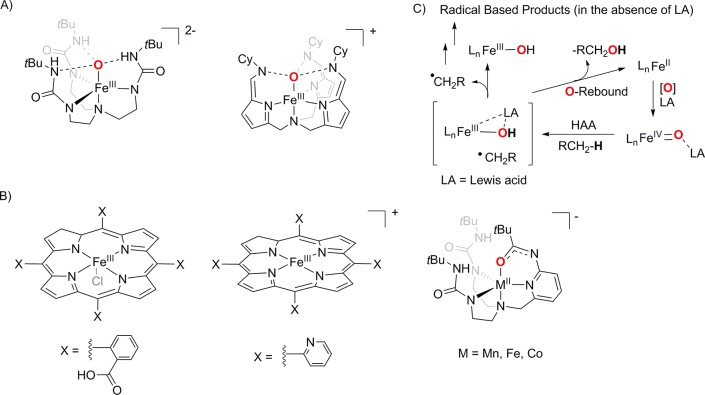

Recently, a number of heme and nonheme iron- and manganese-oxo complexes have been synthesized in biomimetic chemistry, and many of them show intriguing reactivities, which in turn have provided vital insights into the enzymatic reactions. Notably, secondary sphere interactions have been shown to greatly influence the formation and subsequent reactivity of the metal-oxo cores. On one hand, the incorporation of static H-bonds is found to be extremely effective in stabilizing reactive species within transition metal complexes, for example, the reports of the stabilization of the unique oxoiron(III) cores upon dioxygen or N2O activation by employing synthetic ligands (H3buea3– and N(afaCy)3, Figure 9A) that promote intramolecular H-bonds.155,156 Alternatively, the use of a more dynamic secondary sphere by incorporating functional groups that can serve diverse functions such as proton and electron relays can influence the efficiency and product selectivity of the catalytic processes involving metal–oxygen species as reactive intermediates (Figure 9B). For example, the Mayer group has presented a dramatic increase in the rate and selectivity of electrocatalytic O2 reduction to water by Fe tetra-arylporphyrin complexes; the porphyrin ligands (Porp-X4) contain proton delivery functional groups such as carboxylic acids and pyridine to promote reduction of O2 to water rather than hydrogen peroxide.157−159 Similarly, the use of a nonheme [H2bupa]2– ligand containing both intramolecular H-bond donating and accepting groups in the form of urea N–H groups and an anionic amidate group proved effective in the transition-metal mediated catalytic reduction of O2 to water with modest turnover using a sacrificial hydrogen-atom source.160,161 Further, intramolecular secondary sphere interaction of a redox-inactive Lewis acid like scandium triflate or carboxylic or Bronsted acids with metal–oxygen intermediates also led to the formation of highly electrophilic oxidants capable of catalytic hydroxylation of cyclohexane and benzene and enantioselective epoxidation of olefins.147,162−164 These studies corroborate the proposed influence of secondary coordination effects on biological catalysis and have also helped in mimicking the oxidative reactivity of the bioenzymes by employing simple iron and manganese coordination complexes, even in the absence of the extended protein substructures surrounding the enzymes’ active sites. These have opened up totally new perspectives in organic synthesis. Catalysts capable of conducting C–H and C=C oxidation reactions with high product yields and enantioselectivities amenable for high-scale industrial synthesis have been designed. In particular, recent progress in the design of catalysts responsible for enantioselective oxidation of hydrocarbons and syn-dihydroxylation of alkenes is promising and opens up options to replace the industrially used high-valent metal-oxides, like OsO4, RuO4, or MnO4–, which are either very toxic or lead to over oxidation of most substrates.165

Figure 9.

(A) Examples of intramolecular static H-bonding in the secondary coordination sphere leading to the stabilization of oxoiron(III) complexes. (B) Examples of complexes where intramolecular dynamic H-bonding interaction in the secondary sphere leads to the selective reduction of dioxygen to water. (C) Possible role of Lewis acids (LA) in ensuring oxoiron(IV) mediated catalytic C–H bond oxidation reactions.

There are, nevertheless, still some gaps in our present understanding of the chemistry of the reductive dioxygen reaction at transition metal centers for substrate oxidation reactions. In particular, the mechanistic scenario leading to a preferential olefin syn-dihydroxylation reaction (over epoxidation reaction) is not well understood. High-spin FeIII–OOH or FeII–OOH species have been proposed as alternative nucleophilic oxidants that lead to preferential syn-dihydroxylation reactions; however, conclusive evidence is lacking, which makes the mechanism ambiguous.166 Moreover, although several examples of catalytic dioxygen activation reactions at heme iron and manganese centers are known, most of the catalytic systems involving nonheme metal complexes employ H2O2 as the oxidant. The use of O2 in catalytic oxidation reactions is difficult owing to the challenges associated with the addition of sacrificial reductants required to couple the 4e– reduction of O2 with that of the 2e– oxidation of substrates. Although some strategies have been put forward with the aim of developing oxidation methods that employ O2 as oxidant,166 the yields of the oxidized products reported in these studies are still too low for practical use. Further, in spite of the predominance of the oxoiron(IV) cores in biology,1,13,16−19 intermediacy of such cores in catalytic epoxidation and aliphatic C–H functionalization reactions by nonheme iron complexes remains elusive. In addition, although synthetic nonheme iron catalysts for arene-hydroxylation reactions are reported, the nature of the active intermediate(s) has been controversially discussed as both FeIV=O and FeV=O species in the absence of direct spectroscopic evidence. In the context of catalytic C–H bond activation reactions, the reaction is proposed to be initiated by a rate determining H-atom abstraction step by FeIV=O species, followed by an oxygen-rebound between the resulting [FeIII(OH)] and substrate radical species (Figure 9C). In this oxygen-rebound mechanism,71 the formal oxidation state of metal should be reduced by 2e– to Fe2+, and the product formed will then be alcohol. The Fe2+ product can be reoxidized to FeIV=O in the presence of an oxidant leading to catalytic reactions. However, for nonheme oxoiron(IV) model complexes, the dissociation of the substrate radical formed via HAT from hydrocarbons is more favored than the oxygen-rebound process, leading to one electron reduced metal complex products resulting in noncatalytic oxidation reactions.92 One way to deal with this problem will be to enforce Lewis acidic interaction to the FeIV=O cores via modification of the secondary coordination sphere, which will make the iron center electrophilic and will help to speed up the rebound step and ensure a two-electron chemistry, thereby assuring catalysis (Figure 9C). Thus, new and innovative synthetic strategies are needed to generate transition metal complexes that can efficiently use O2 as the terminal oxidant, in order to achieve challenging oxidation of substrates like functionalization of C–H bonds and syn-dihydroxylation of arenes.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of their collaborators and co-workers in the cited references, and the financial support by the NRF of Korea through CRI (NRF-2012R1A3A2048842 to W.N.) and GRL (NRF-2010-00353 to W.N.). K.R. thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (UniCat; EXC 314-2 and Heisenberg Professorship). T.C. gratefully acknowledges the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship.

Author Contributions

# M.G. and T.C. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Sahu S.; Goldberg D. P. Activation of Dioxygen by Iron and Manganese Complexes: A Heme and Nonheme Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11410–11428. 10.1021/jacs.6b05251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva E. G.; Lipscomb J. D. Versatility of Biological Non-Heme Fe(II) Centers in Oxygen Activation Reactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 186–193. 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau M. Y. M.; Lipscomb J. D.; Solomon E. I. Substrate Activation for O2 Reactions by Oxidized Metal Centers in Biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 18355–18362. 10.1073/pnas.0704191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. D.; Summerville D. A.; Basolo F. Synthetic Oxygen Carriers Related to Biological Systems. Chem. Rev. 1979, 79, 139–179. 10.1021/cr60318a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood P. M. The Potential Diagram for Oxygen at pH 7. Biochem. J. 1988, 253, 287–289. 10.1042/bj2530287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que L. Jr. 60 Years of Dioxygen Activation. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 171–173. 10.1007/s00775-017-1443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam W. Dioxygen Activation by Metalloenzymes and Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 465–465. 10.1021/ar700131d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W. Mechanisms of Two-Electron versus Four-Electron Reduction of Dioxygen Catalyzed by Earth-Abundant Metal Complexes. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 9–28. 10.1002/cctc.201701064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Lai W.; Cao R. Energy-Related Small Molecule Activation Reactions: Oxygen Reduction and Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution Reactions Catalyzed by Porphyrin- and Corrole-Based Systems. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 3717–3797. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastri F.; Chino M.; Maglio O.; Bhagi-Damodaran A.; Lu Y.; Lombardi A. Design and Engineering of Artificial Oxygen-Activating Metalloenzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5020–5054. 10.1039/C5CS00923E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hematian S.; Garcia-Bosch I.; Karlin K. D. Synthetic Heme/Copper Assemblies: Toward an Understanding of Cytochrome c Oxidase Interactions with Dioxygen and Nitrogen Oxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2462–2474. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasniewski A. J.; Que L. Jr. Dioxygen Activation by Nonheme Diiron Enzymes: Diverse Dioxygen Adducts, High-Valent Intermediates, and Related Model Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2554–2592. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Groves J. T. Oxygen Activation and Radical Transformations in Heme Proteins and Metalloporphyrins. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2491–2553. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I.; Goudarzi S.; Sutherlin K. D. O2 Activation by Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6363–6374. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos T. L. Heme Enzyme Structure and Function. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3919–3962. 10.1021/cr400415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Omar M. M.; Loaiza A.; Hontzeas N. Reaction Mechanisms of Mononuclear Non-Heme Iron Oxygenases. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2227–2252. 10.1021/cr040653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I.; Brunold T. C.; Davis M. I.; Kemsley J. N.; Lee S.-K.; Lehnert N.; Neese F.; Skulan A. J.; Yang Y.-S.; Zhou J. Geometric and Electronic Structure/Function Correlations in Non-Heme Iron Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 235–350. 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K.; Pfaff F. F.; Wang B.; Nam W. Status of Reactive Non-Heme Metal–Oxygen Intermediates in Chemical and Enzymatic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13942–13958. 10.1021/ja507807v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon E. I.; Light K. M.; Liu L. V.; Srnec M.; Wong S. D. Geometric and Electronic Structure Contributions to Function in Non-heme Iron Enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2725–2739. 10.1021/ar400149m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach P. L.; Clifton I. J.; Hensgens C. M. H.; Shibata N.; Schofield C. J.; Hajdu J.; Baldwin J. E. Structure of IsopenicillinN Synthase Complexed with Substrate and the Mechanism of Penicillin Formation. Nature 1997, 387, 827–830. 10.1038/42990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam W. Synthetic Mononuclear Nonheme Iron–Oxygen Intermediates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2415–2423. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.; Sutherlin K. D.; Park J.; Kwon E.; Siegler M. A.; Solomon E. I.; Nam W. Crystallographic and Spectroscopic Characterization and Reactivities of A Mononuclear Non-Haem Iron(III)-Superoxo Complex. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5440–5446. 10.1038/ncomms6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C.-W.; Kleespies S. T.; Stout H. D.; Meier K. K.; Li P.-Y.; Bominaar E. L.; Que L. Jr.; Münck E.; Lee W.-Z. Characterization of a Paramagnetic Mononuclear Nonheme Iron-Superoxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10846–10849. 10.1021/ja504410s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang S.; Lee Y.-M.; Hong S.; Cho K.-B.; Nishida Y.; Seo M. S.; Sarangi R.; Fukuzumi S.; Nam W. Redox-Inactive Netal Ions Modulate the Reactivity and Oxygen Release of Mononuclear Non-Haem Iron(III)–Peroxo Complexes. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 934–940. 10.1038/nchem.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J.; Jeon S.; Wilson S. A.; Liu L. V.; Kang E. A.; Braymer J. J.; Lim M. H.; Hedman B.; Hodgson K. O.; Valentine J. S.; Solomon E. I.; Nam W. Structure and Reactivity of A Mononuclear Non-Haem Iron(III)–Peroxo Complex. Nature 2011, 478, 502–505. 10.1038/nature10535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira F. T.; Chanda A.; Banerjee D.; Shan X.; Mondal S.; Que L. Jr.; Bominaar E. L.; Münck E.; Collins T. J. Chemical and Spectroscopic Evidence for an FeV-Oxo Complex. Science 2007, 315, 835–838. 10.1126/science.1133417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski M. R.; Koehntop K. D.; Stubna A.; Bominaar E. L.; Halfen J. A.; Münck E.; Nam W.; Que L. Jr. A Thiolate-Ligated Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) Complex Relevant to Cytochrome P450. Science 2005, 310, 1000–1002. 10.1126/science.1119092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde J.-U.; In J.-H.; Lim M. H.; Brennessel W. W.; Bukowski M. R.; Stubna A.; Münck E.; Nam W.; Que L. Jr. Crystallographic and Spectroscopic Characterization of a Nonheme Fe(IV)=O Complex. Science 2003, 299, 1037–1039. 10.1126/science.299.5609.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. T.; Haushalter R. C.; Nakamura M.; Nemo T. E.; Evans B. J. High-Valent Iron-Porphyrin Complexes related to Peroxidase and Cytochrome P-450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 2884–2886. 10.1021/ja00400a075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puri M.; Que L. Jr. Toward the Synthesis of More Reactive S = 2 Non-Heme Oxoiron(IV) Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2443–2452. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann X.; Monte-Pérez I.; Ray K. Oxidation Reactions with Bioinspired Mononuclear Non-Heme Metal–Oxo Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7632–7649. 10.1002/anie.201600507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigi J. P.; Harman W. H.; Lassalle-Kaiser B.; Robles D. M.; Stich T. A.; Yano J.; Britt R. D.; Chang C. J. A High-Spin Iron(IV)–Oxo Complex Supported by a Trigonal Nonheme Pyrrolide Platform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 1536–1542. 10.1021/ja207048h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England J.; Martinho M.; Farquhar E. R.; Frisch J. R.; Bominaar E. L.; Münck E.; Que L. Jr. A Synthetic High-Spin Oxoiron(IV) Complex: Generation, Spectroscopic Characterization, and Reactivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3622–3626. 10.1002/anie.200900863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oloo W. N.; Que L. Jr. Bioinspired Nonheme Iron Catalysts for C-H and C = C Bond Oxidation: Insights into the Nature of the Metal-Based Oxidants. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2612–2621. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Groves J. T. Manganese Catalyzed C–H Halogenation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1727–1735. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussó O.; Ribas X.; Costas M. Biologically Inspired Non-Heme Iron-Catalysts for Asymmetric Epoxidation; Design Principles and Perspectives. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14285–14298. 10.1039/C5CC05576H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosca T. H.; Green M. T. Preparation of Compound I in P450cam: the Prototypical P450. Isr. J. Chem. 2016, 56, 834–840. 10.1002/ijch.201600013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krest C. M.; Silakov A.; Rittle J.; Yosca T. H.; Onderko E. L.; Calixto J. C.; Green M. T. Significantly Shorter Fe–S Bond in Cytochrome P450-I Is Consistent with Greater Reactivity Relative to Chloroperoxidase. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 696–702. 10.1038/nchem.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittle J.; Green M. T. Cytochrome P450 Compound I: Capture, Characterization, and C-H Bond Activation Kinetics. Science 2010, 330, 933–937. 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T.; Shimada H.; Ishimura Y. Evidence for Compound I Formation in the Reaction of Cytochrome-P450cam with m-Chloroperbenzoic Acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 201, 1464–1469. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. T. The Structure and Spin Coupling of Catalase Compound I: A Study of Noncovalent Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9218–9219. 10.1021/ja010105h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khindaria A.; Aust S. D. EPR Detection and Characterization of Lignin Peroxidase Porphyrin π-Cation Radical. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 13107–13111. 10.1021/bi961297+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson W. R.; Poulos T. L.; Goodin D. B. Identification of a Porphyrin π Cation Radical in Ascorbate Peroxidase Compound I. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4342–4345. 10.1021/bi00013a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasena R. E. P.; Vatsis K. P.; Coon M. J.; Hollenberg P. F.; Newcomb M. Hydroxylation by the Hydroperoxy-Iron Species in Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 115–126. 10.1021/ja038237t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M.; Aebisher D.; Shen R.; Chandrasena R. E. P.; Hollenberg P. F.; Coon M. J. Kinetic Isotope Effects Implicate Two Electrophilic Oxidants in Cytochrome P450-Catalyzed Hydroxylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6064–6065. 10.1021/ja0343858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam W.; Ryu Y.; Song W. Oxidizing Intermediates in Cytochrome P450 Model Reactions. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 9, 654–660. 10.1007/s00775-004-0577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K.-B.; Hirao H.; Shaik S.; Nam W. To Rebound or Dissociate? This Is the Mechanistic Question in C-H Hydroxylation by Heme and Nonheme Metal-Oxo Complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1197–1210. 10.1039/C5CS00566C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. T.; Van der Puy M. Stereospecific Aliphatic Hydroxylation by Iron-Hydrogen Peroxide. Evidence for a Stepwise Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 5290–5297. 10.1021/ja00433a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. T.; McClusky G. A. Aliphatic Hydroxylation via Oxygen Rebound. Oxygen Transfer Catalyzed by Iron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 859–861. 10.1021/ja00419a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Peter S.; Kinne M.; Hofrichter M.; Groves J. T. Detection and Kinetic Characterization of a Highly Reactive Heme–Thiolate Peroxygenase Compound I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12897–12900. 10.1021/ja3049223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosca T. H.; Rittle J.; Krest C. M.; Onderko E. L.; Silakov A.; Calixto J. C.; Behan R. K.; Green M. T. Iron(IV)hydroxide pKa and the Role of Thiolate Ligation in C–H Bond Activation by Cytochrome P450. Science 2013, 342, 825–829. 10.1126/science.1244373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Ullrich R.; Hofrichter M.; Groves J. T. Heme-Thiolate Ferryl of Aromatic Peroxygenase Is Basic and Reactive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 3686–3691. 10.1073/pnas.1503340112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell F. G. Equilibrium Acidities in Dimethyl Sulfoxide Solution. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988, 21, 456–463. 10.1021/ar00156a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H. Electronic Structure and Reactivity of High-Valent Oxo Iron Porphyrins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 226, 51–60. 10.1016/S0010-8545(01)00441-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin D.; Traylor T. G.; Xie L. Y. Polyhaloporphyrins: Unusual Ligands for Metals and Metal-Catalyzed Oxidations. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 251–259. 10.1021/ar960126u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costas M. Selective C–H Oxidation Catalyzed by Metalloporphyrins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2912–2932. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y.; Nakajima H.; Ueno T. Reactivities of Oxo and Peroxo Intermediates Studied by Hemoprotein Mutants. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 554–562. 10.1021/ar600046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Groves J. T. Beyond Ferryl-Mediated Hydroxylation: 40 Years of the Rebound Mechanism and C–H Activation. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 185–207. 10.1007/s00775-016-1414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder D.; Shaik S.; Schwarz H. Two-State Reactivity as a New Concept in Organometallic Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 139–145. 10.1021/ar990028j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S.; de Visser S. P.; Ogliaro F.; Schwarz H.; Schröder D. Two-State Reactivity Mechanisms of Hydroxylation and Epoxidation by Cytochrome P-450 Revealed by Theory. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002, 6, 556–567. 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S.; Kumar D.; de Visser S. P.; Altun A.; Thiel W. Theoretical Perspective on the Structure and Mechanism of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2279–2328. 10.1021/cr030722j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin N.; Groves J. T. Unusual Kinetic Stability of a Ground-State Singlet Oxomanganese(V) Porphyrin. Evidence for a Spin State Crossing Effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2923–2924. 10.1021/ja984429q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin N.; Ibrahim M.; Spiro T. G.; Groves J. T. Trans-dioxo Manganese(V) Porphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12416–12417. 10.1021/ja0761737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis F.; Jin N.; Car R.; Groves J. T. Electronic Structure and Reactivity of Isomeric Oxo-Mn(V) Porphyrins: Effects of Spin-State Crossing and pKa Modulation. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 4268–4276. 10.1021/ic060306s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A.; Kurahashi T.; Fujii H. Redox Potentials of Oxoiron(IV) Porphyrin π-Cation Radical Complexes: Participation of Electron Transfer Process in Oxygenation Reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 6922–6928. 10.1021/ic102564e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. R.; Groves J. T. A Highly Reactive P450 Model Compound I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9640–9641. 10.1021/ja903394s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.; Chen H.; Jeong Y. J.; Lai W.; Bae E. H.; Shaik S.; Nam W. Enhanced Reactivities of Iron(IV)-Oxo Porphyrin π-Cation Radicals in Oxygenation Reactions by Electron-Donating Axial Ligands. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15, 10039–10046. 10.1002/chem.200901238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcells D.; Raynaud C.; Crabtree R. H.; Eisenstein O. A Rational Basis for the Axial Ligand Effect in C–H Oxidation by [MnO(porphyrin)(X)]+ (X = H2O, OH–, O2–) from a DFT Study. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 10090–10099. 10.1021/ic8013706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A.; Yamaki D.; Ikemura K.; Kurahashi T.; Ogura T.; Hada M.; Fujii H. Effect of the Axial Ligand on the Reactivity of the Oxoiron(IV) Porphyrin π-Cation Radical Complex: Higher Stabilization of the Product State Relative to the Reactant State. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 7296–7305. 10.1021/ic3006597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Cheng M.-J.; Nielsen R. J.; Goddard W. A.; Groves J. T. Probing the C–O Bond-Formation Step in Metalloporphyrin-Catalyzed C–H Oxygenation Reactions. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4182–4188. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. T.; Nemo T. E.; Myers R. S. Hydroxylation and Epoxidation Catalyzed by Iron-Porphine Complexes. Oxygen Transfer from Iodosylbenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 1032–1033. 10.1021/ja00498a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalaiah K. Chiral Iron Catalysts for Asymmetric Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3248–3296. 10.1021/cr300236r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose E.; Andrioletti B.; Zrig S.; Quelquejeu-Ethève M. Enantioselective Epoxidation of Olefins with Chiral Metalloporphyrin Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 573–583. 10.1039/b405679p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier B. Metalloporphyrins as Versatile Catalysts for Oxidation Reactions and Oxidative DNA Cleavage. Chem. Rev. 1992, 92, 1411–1456. 10.1021/cr00014a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. K.; Kuo M.-S. Reaction of Iron(III) Porphyrins and Iodosoxylene. The Active Oxene Complex of Cytochrome P-450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 3413–3415. 10.1021/ja00506a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P. E.; Lyons J. E. Selective Air Oxidation of Light Alkanes Catalyzed by Activated Metalloporphyrins - the Search for a Suprabiotic System. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1990, 105, 181–193. 10.1016/0010-8545(90)80022-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Dilger A. K.; Cheng P. T.; Ewing W. R.; Groves J. T. Selective C–H Halogenation with a Highly Fluorinated Manganese Porphyrin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1251–1255. 10.1002/anie.201710676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Zhuang T.; Kates P. A.; Gao H.; Chen X.; Groves J. T. Alkyl Isocyanates via Manganese-Catalyzed C–H Activation for the Preparation of Substituted Ureas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15407–15413. 10.1021/jacs.7b07658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C.; Galonić Fujimori D.; Walsh C. T.; Bollinger J. M. Jr. Non-Heme Fe(IV)–Oxo Intermediates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 484–492. 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. C.; Barr E. W.; Tirupati B.; Bollinger J. M. Jr.; Krebs C. The First Direct Characterization of a High-Valent Iron Intermediate in the Reaction of an α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenase: A High-Spin Fe(IV) Complex in Taurine/α-Ketoglutarate Dioxygenase (TauD) from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 7497–7508. 10.1021/bi030011f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proshlyakov D. A.; Henshaw T. F.; Monterosso G. R.; Ryle M. J.; Hausinger R. P. Direct Detection of Oxygen Intermediates in the Non-Heme Fe Enzyme Taurine/α-Ketoglutarate Dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1022–1023. 10.1021/ja039113j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs-Gelasco P. J.; Price J. C.; Guyer R. B.; Brehm J. H.; Barr E. W.; Bollinger J. M. Jr.; Krebs C. EXAFS Spectroscopic Evidence for an Fe = O Unit in the Fe(IV) Intermediate Observed during Oxygen Activation by Taurine:α-Ketoglutarate Dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8108–8109. 10.1021/ja048255q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. D.; Srnec M.; Matthews M. L.; Liu L. V.; Kwak Y.; Park K.; Bell C. B. III; Alp E. E.; Zhao J.; Yoda Y.; Kitao S.; Seto M.; Krebs C.; Bollinger J. M. Jr.; Solomon E. I. Elucidation of the Fe(IV)=O Intermediate in the Catalytic Cycle of the Halogenase SyrB2. Nature 2013, 499, 320–323. 10.1038/nature12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. C.; Barr E. W.; Glass T. E.; Krebs C.; Bollinger J. M. Jr. Evidence for Hydrogen Abstraction from C1 of Taurine by the High-Spin Fe(IV) Intermediate Detected during Oxygen Activation by Taurine:α-Ketoglutarate Dioxygenase (TauD). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13008–13009. 10.1021/ja037400h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panay A. J.; Fitzpatrick P. F. Kinetic Isotope Effects on Aromatic and Benzylic Hydroxylation by Chromobacterium violaceum Phenylalanine Hydroxylase as Probes of Chemical Mechanism and Reactivity. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 11118–11124. 10.1021/bi801295w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panay A. J.; Lee M.; Krebs C.; Bollinger J. M. Jr.; Fitzpatrick P. F. Evidence for a High-Spin Fe(IV) Species in the Catalytic Cycle of a Bacterial Phenylalanine Hydroxylase. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1928–1933. 10.1021/bi1019868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eser B. E.; Barr E. W.; Frantom P. A.; Saleh L.; Bollinger J. M. Jr.; Krebs C.; Fitzpatrick P. F. Direct Spectroscopic Evidence for a High-Spin Fe(IV) Intermediate in Tyrosine Hydroxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11334–11335. 10.1021/ja074446s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantom P. A.; Pongdee R.; Sulikowski G. A.; Fitzpatrick P. F. Intrinsic Deuterium Isotope Effects on Benzylic Hydroxylation by Tyrosine Hydroxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 4202–4203. 10.1021/ja025602s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. J.; Benkovic S. J. L-[2,5-H2]Phenylalanine, an Alternate Substrate for Rat Liver Phenylalanine Hydroxylase. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 3658–3663. 10.1021/bi00410a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W.; Song H.; Song F.; Guo Y.; Wu C.-H.; Sae Her A.; Pu Y.; Wang S.; Naowarojna N.; Weitz A.; Hendrich M. P.; Costello C. E.; Zhang L.; Liu P.; Jessie Zhang Y. Endoperoxide Formation by an α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Mononuclear Non-Haem Iron Enzyme. Nature 2015, 527, 539–543. 10.1038/nature15519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Grapperhaus C. A.; Mienert B.; Bill E.; Weyhermüller T.; Wieghardt K. Mononuclear (Nitrido)iron(V) and (Oxo)iron(IV) Complexes via Photolysis of [(cyclam-acetato)FeIII(N3)]+ and Ozonolysis of [(cyclam-acetato)FeIII(O3SCF3)]+ in Water/Acetone Mixtures. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 5306–5317. 10.1021/ic0005238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam W.; Lee Y.-M.; Fukuzumi S. Tuning Reactivity and Mechanism in Oxidation Reactions by Mononuclear Nonheme Iron(IV)-Oxo Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1146–1154. 10.1021/ar400258p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usharani D.; Janardanan D.; Li C.; Shaik S. A Theory for Bioinorganic Chemical Reactivity of Oxometal Complexes and Analogous Oxidants: The Exchange and Orbital-Selection Rules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 471–482. 10.1021/ar300204y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. R.; Que L. Jr. High-Valent Nonheme Iron-Oxo Complexes: Synthesis, Structure, and Spectroscopy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 414–428. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenberger J.; Ray K.; Meyer K. The Biology and Chemistry of High-Valent Iron–Oxo and Iron–Nitrido Complexes. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 720–732. 10.1038/ncomms1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S.; Chen H.; Janardanan D. Exchange-Enhanced Reactivity in Bond Activation by Metal–Oxo Enzymes and Synthetic Reagents. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 19–27. 10.1038/nchem.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao H.; Que L. Jr.; Nam W.; Shaik S. A Two-State Reactivity Rationale for Counterintuitive Axial Ligand Effects on the C-H Activation Reactivity of Nonheme FeIV=O Oxidants. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 1740–1756. 10.1002/chem.200701739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastri C. V.; Lee J.; Oh K.; Lee Y. J.; Lee J.; Jackson T. A.; Ray K.; Hirao H.; Shin W.; Halfen J. A.; Kim J.; Que L. Jr.; Shaik S.; Nam W. Axial Ligand Tuning of a Nonheme Iron(IV)–Oxo Unit for Hydrogen Atom Abstraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 19181–19186. 10.1073/pnas.0709471104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S.; Zhang B.; Pollock C. J.; Dürr M.; Davies C. G.; Confer A. M.; Ivanović-Burmazović I.; Siegler M. A.; Jameson G. N. L.; Krebs C.; Goldberg D. P. Aromatic C–F Hydroxylation by Nonheme Iron(IV)–Oxo Complexes: Structural, Spectroscopic, and Mechanistic Investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 12791–12802. 10.1021/jacs.6b03346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S.; Quesne M. G.; Davies C. G.; Dürr M.; Ivanović-Burmazović I.; Siegler M. A.; Jameson G. N. L.; de Visser S. P.; Goldberg D. P. Direct Observation of a Nonheme Iron(IV)–Oxo Complex That Mediates Aromatic C–F Hydroxylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13542–13545. 10.1021/ja507346t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.; Neese F. Nonheme Oxo-Iron(IV) Intermediates Form an Oxyl Radical upon Approaching the C–H Bond Activation Transition State. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 1228–1233. 10.1073/pnas.1008411108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S.; Hirao H.; Kumar D. Reactivity of High-Valent Iron–Oxo Species in Enzymes and Synthetic Reagents: A Tale of Many States. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 532–542. 10.1021/ar600042c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas A. N.; Puri M.; Meier K. K.; Oloo W. N.; Rohde G. T.; Bominaar E. L.; Münck E.; Que L. Jr. Modeling TauD-J: A High-Spin Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) Complex with High Reactivity toward C-H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2428–2431. 10.1021/ja511757j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M. S.; Kim N. H.; Cho K.-B.; So J. E.; Park S. K.; Clemancey M.; Garcia-Serres R.; Latour J.-M.; Shaik S.; Nam W. A Mononuclear Nonheme Iron(IV)-Oxo Complex Which Is More Reactive Than Cytochrome P450 Model Compound I. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1039–1045. 10.1039/c1sc00062d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monte-Pérez I.; Engelmann X.; Lee Y.-M.; Yoo M.; Kumaran E.; Farquhar E. R.; Bill E.; England J.; Nam W.; Swart M.; Ray K. A Highly Reactive Oxoiron(IV) Complex Supported by a Bioinspired N3O Macrocyclic Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14384–14388. 10.1002/anie.201707872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper C.; Mondal B.; Serrano-Plana J.; Klawitter I.; Neese F.; Costas M.; Ye S.; Meyer F. Nonclassical Single-State Reactivity of an Oxo-Iron(IV) Complex Confined to Triplet Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8939–8949. 10.1021/jacs.7b03255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.; Kupper C.; Meyer S.; Andris E.; Navrátil R.; Krahe O.; Mondal B.; Atanasov M.; Bill E.; Roithová J.; Meyer F.; Neese F. Magnetic Circular Dichroism Evidence for an Unusual Electronic Structure of a Tetracarbene–Oxoiron(IV) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14312–14325. 10.1021/jacs.6b07708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S.; Klawitter I.; Demeshko S.; Bill E.; Meyer F. A Tetracarbene–Oxoiron(IV) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 901–905. 10.1002/anie.201208044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari A.; Kaushik A.; Rajaraman G. Mechanistic Insights on the ortho-Hydroxylation of Aromatic Compounds by Non-heme Iron Complex: A Computational Case Study on the Comparative Oxidative Ability of Ferric-Hydroperoxo and High-Valent FeIV=O and FeV=O Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4235–4249. 10.1021/ja307077f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srnec M.; Wong S. D.; England J.; Que L. Jr.; Solomon E. I. π-Frontier Molecular Orbitals in S = 2 Ferryl Species and Elucidation of Their Contributions to Reactivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 14326–14331. 10.1073/pnas.1212693109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. R.; Guo Y.; Vu V. V.; Bominaar E. L.; Münck E.; Que L. Jr. A Mononuclear Carboxylate-Rich Oxoiron(IV) Complex: A Structural and Functional Mimic of TauD Intermediate ‘J’. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 1680–1693. 10.1039/c2sc01044e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser S. P.; Oh K.; Han A.-R.; Nam W. Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study on Aromatic Hydroxylation by Mononuclear Nonheme Iron(IV)–Oxo Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 4632–4641. 10.1021/ic700462h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S.; Widger L. R.; Quesne M. G.; de Visser S. P.; Matsumura H.; Moënne-Loccoz P.; Siegler M. A.; Goldberg D. P. Secondary Coordination Sphere Influence on the Reactivity of Nonheme Iron(II) Complexes: An Experimental and DFT Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10590–10593. 10.1021/ja402688t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S.; Kotani H.; Suenobu T.; Hong S.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W. Contrasting Effects of Axial Ligands on Electron-Transfer Versus Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer Reactions of Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) Complexes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 354–361. 10.1002/chem.200901163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T. A.; Rohde J.-U.; Seo M. S.; Sastri C. V.; DeHont R.; Stubna A.; Ohta T.; Kitagawa T.; Münck E.; Nam W.; Que L. Jr. Axial Ligand Effects on the Geometric and Electronic Structures of Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12394–12407. 10.1021/ja8022576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal D.; Ramanan R.; Usharani D.; Janardanan D.; Wang B.; Shaik S. How Does Tunneling Contribute to Counterintuitive H-Abstraction Reactivity of Nonheme Fe(IV)O Oxidants with Alkanes?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 722–733. 10.1021/ja509465w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S.; Morimoto Y.; Kotani H.; Naumov P.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W. Crystal Structure of a Metal Ion-Bound Oxoiron(IV) Complex and Implications for Biological Electron Transfer. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 756–759. 10.1038/nchem.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto Y.; Kotani H.; Park J.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W.; Fukuzumi S. Metal Ion-Coupled Electron Transfer of a Nonheme Oxoiron(IV) Complex: Remarkable Enhancement of Electron-Transfer Rates by Sc3+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 403–405. 10.1021/ja109056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Morimoto Y.; Lee Y.-M.; Nam W.; Fukuzumi S. Proton-Promoted Oxygen Atom Transfer vs Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer of a Non-Heme Iron(IV)-Oxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3903–3911. 10.1021/ja211641s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. J.; Brennan B. J.; Tagore R.; Brudvig G. W. Photosynthetic Water Oxidation: Insights from Manganese Model Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 567–574. 10.1021/ar5004175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J.; Yachandra V. Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosynthesis: Where and How Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4175–4205. 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.; Pantazis D. A.; Neese F.; Lubitz W. Biological Water Oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1588–1596. 10.1021/ar3003249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocera D. G. The Artificial Leaf. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 767–776. 10.1021/ar2003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryliakov K. P. Catalytic Asymmetric Oxygenations with the Environmentally Benign Oxidants H2O2 and O2. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11406–11459. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]