ABSTRACT

Suicide is a major public health issue across the Arctic, especially among Indigenous Peoples. The aim of this study was to explore and describe cultural meanings of suicide among Sámi in Norway. Five open-ended focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with 22 Sámi (20) and non-Sámi (2) participants in South, Lule, Marka, coastal and North Sámi communities in Norway. FGDs were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed employing thematic analysis. Six themes were developed from the analysis: “Sámi are treated negatively by the majority society”, “Some Sámi face negative treatment from other Sámi”, “The historic losses of the Sámi have turned into a void”, “Sámi are not provided with equal mental health care”, “The strong Sámi networks have both positive and negative impacts” and “‘Birgetkultuvvra’ might be a problem”. The findings indicate that the participants understand suicide among Sámi in relation to increased problem load for Sámi (difficulties in life not encountered by non-Sámi) and inadequate problem-solving mechanisms on different levels, including lack of equal mental health care for Sámi and cultural values of managing by oneself (“ieš birget”). The findings are important when designing suicide prevention initiatives specifically targeting Sámi.

KEYWORDS: Sami, Saami, focus group discussions, mental health, Sápmi, Sapmi

Introduction and background

Suicide among Indigenous peoples in the Arctic and Sápmi

Suicide is a major public health issue across the Arctic [1], and statistics from Alaska, the United States [2], Nunavut, Canada [3], Greenland [4] and northern Russia [1,5] show alarming suicide rates, especially among the Indigenous peoples of the north. Suicide rates are moderate in arctic Norway and Sweden, but Sámi have died more often from suicide than majority populations [1,6–8]. As is the case among many other Indigenous people in the Arctic; “harder” methods (including weapons and hanging), suicide clusters, and elevated suicide rates for young men are found more commonly among Sámi than in majority populations [1]. Studies from Sweden have also indicated that each suicide among Sámi might have broader social impacts, leaving more people bereaved, possibly due to the extended family networks among the Sámi [9,10].

The Sámi context

Sámi have lived in Sápmi (the Sámi homelands; in Arctic and sub-arctic parts of Scandinavia and the Kola peninsula in Russia) since time immemorial. Sámi have their own languages and cultures, traditionally based on subsistence such as hunting, fishing, herding reindeer and small-scale farming. However, the Sámi societies of today are characterised by a broad and diversified spectrum of traditional and modern/western values and livelihoods.

As many other Indigenous peoples, the Sámi have also been colonised. In Norway, the Norwegianization period started in the 19th century, a governmental policy aiming at assimilating the Sámi people into the majority population. This policy was enforced, for example, through placing Sámi children in boarding schools where their languages were prohibited, and not allowing individuals without Norwegian names and language skills to buy land [11]. As a result of the Norwegianization and the lack of ethnic registries it is unknown how many Sámi there are today. However, Sámi have organised themselves in resistance, which during the last 50 years has gained political momentum resulting in official recognition of Sámi as an Indigenous people, establishment of Sámi parliaments in Norway, Sweden and Finland, as well as revitalisation of Sámi languages and cultures. Furthermore, the Norwegian government has made an agreement with the Sámi Parliament in Norway to consult with the Sámi on matters affecting them, as well as to organise a truth commission to investigate the Norwegianisation policy and other injustices against the Sámi people [12].

Culture and context in suicide

Mainstream suicidology has for a long time focused on uncovering risk factors for suicide and suicidal behaviour; such as mental health problems, including alcohol and drug abuse. Critics argue that that line of research has reached a dead end in terms of coming up with better methods for suicide prevention, and instead emphasise that qualitative research into cultural and contextual aspects of suicide could be a way forward [13–15]. That corresponds well with the dominant discourse within Indigenous suicidology, which points out that one must look at the historical and social underpinnings to understand the contemporary suicide and mental health crisis among Indigenous persons [16,17]. Those underpinnings include the historical and on-going colonisation and general modernisation processes which have brought societal turmoil through rapid and fundamental changes as well as weakening of traditional societal structures, languages and cultures.

What “culture” is is debated, but the following definition has been proposed by Marsella et al. [18]. “shared acquired patterns of behavior and meanings that are constructed and transmitted within social-life contexts for the purposes of promoting individual and group survival, adaptation, and adjustment. These shared acquired patterns are dynamic in nature (i.e. continuously subject to change and revision) and can become dysfunctional.”

Qualitative methodology is well suited to consider cultural and contextual issues in relation to suicide [14,15,19]. Focus group discussions (FGDs) have previously been used to investigate cultural understandings of suicide in specific populations [20,21], also among Indigenous peoples in the Arctic [22–24]. The study by Stoor et al [24] explored the cultural meanings of suicide among Sámi in Sweden and found that it was understood to be connected to difficulties of maintaining Sámi identity, i.e. to maintain the traditional reindeer herding culture in face of difficulties posed by modern society and lack of (Sámi) political power. Such inside perspectives complement the discourse on suicide prevention to include sociocultural and contextual aspects, which is considered crucial if one wants to reduce suicide among Indigenous peoples in the north [25–28].

The aim of this study is to explore and describe cultural meanings of suicide among Sámi in Norway.

Method

Positioning

The research group consisted of two Sámi (first and second author) and two people from the majority population in Norway (third and last author). The last author has long-standing work relations with Sámi communities. We acknowledge that our subject positions have impacts on our research, including how participants regard and interact with us; in turn affecting how and what data can be gathered, as well as our scope and competencies in interpreting and analysing the findings. We acknowledge that the interdependent nature of relationships within the Sámi world is key to getting the trust necessary from participants. This means that we could not have carried out this study without some of us being “insiders”, that is, Sámi.

Sample

Twenty-two participants were recruited through snow-ball sampling technique, based on the personal and professional networks of the first and last author, as well as colleagues at the Sámi Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Mental Health and Substance Abuse (Finnmark hospital trust) and Centre for Sámi Health Research (UiT – the Arctic University of Norway). Participants were chosen based on their knowledge and experience with suicide among Sámi (including being bereaved, but not within the last year), their professional work in mental health and/or suicide prevention and their formal and informal roles as community leaders. Furthermore, recruitment aimed at including participants with diverse personal backgrounds in terms of ethnic background, work experience, sex, age and experience(s) of suicide among Sámi (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| No. of participants | 22 |

| Sex | 15 women, 7 men |

| Age | 19–74 years, mean 48,6 y (male = 50,7 y, female = 47,6 y), median 47,5 y |

| Profession | Mental health workers, suicide prevention workers, cultural workers (artists, language workers, personnel in cultural centres), reindeer herders, fishermen, politicians, students and retired. |

| Ethnic background | Sámi (n = 20) and non-Sámi (n = 2). |

Procedure

Five focus group discussions (FGDs), varying in length between 105 and 125 min, were held during spring 2014 in South, Lule, Marka, coastal and North Sámi areas on the Norwegian side of Sápmi. Participants were contacted, informed, and invited to participate by phone. Those interested received the same information by email (or regular mail, if preferred) and again at the scene of the FGD, where they also gave their written informed consent. The procedure included resources, time and space for culturally appropriate activities such as revealing kinships (and other important relationships) as well as sharing a meal before the FGD. Participants were also reimbursed for travel expenses and lost job income. To ensure authentic and rich discussions, the participants were encouraged to agree on voluntary confidentiality and to speak their mind as they would have done “in an ordinary conversation on the topic”. Furthermore, care was taken to allow participants to be in control of the narrative they created, on their own and as a focus group. Thus, the FGD was open ended and the only predetermined prompting question was; “When talking about suicide among Sámi, what do you think is most important that we talk about?”

FGDs were facilitated by the first and last author, who took turns being active and passive. The active facilitator supported the participants as they shared their views, asked for more opinions, made sure that everyone was heard and respected and in general helped to keep the group on track (posed follow-up questions, clarified meanings etc.). The passive facilitator took notes and presented those before the ending of the FGDs, which gave the participants a chance to withdraw statements, clarify what they meant and/or add more topics, should they want to. The facilitators discussed the notes after each FGD in order to be able to identify and follow up interesting topics during the subsequent FGDs. The discussions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The total data corpus (all transcripts) includes 82,969 words.

Ethics

The study adhered to the Helsinki declaration [29], that is by allowing all participants informed consent and the right to withdraw from the study without stating any reason or suffering other negative consequences. Furthermore, in line with a proposal for ethical guidelines in Sámi medical research [30], we sought to create a culturally safe context for all participants, in this instance for example through sharing food and revealing kinships before the FGD. The Norwegian Centre for Research Data approved the study.

Analysis

The analysis was inductive and guided by thematic analysis as formulated by Braun and Clarke [31], with the aim to systematically explore the data in search of re-emerging patterns reflecting cultural meanings of suicide, and then define, demarcate and describe those patterns.

All authors read all the transcripts and took notes, highlighting interesting excerpts. The first author constructed mind maps (one per FGD) with excerpts sorted in preliminary sub- and main categories. The authors then compared notes, discussed the mind maps and agreed on what the re-emerging patterns of meaning were, creating a preliminary thematic structure. The first author then engaged in a trial and error process, moving around excerpts and categories, ending in the construction of new mind maps based on the agreed upon themes (one per theme). As the latent content of a few excerpts and categories was possible to interpret in different ways, they were allowed to belong to more than one theme. The first author described and named each category and theme and all authors discussed those and checked that interpretations were reasonable.

Findings

The analysis resulted in 44 categories belonging to 6 themes (see Table 2) and 1 single category not belonging to any theme. The single category was made up of seven excerpts interpreted as direct or indirect critique of understanding suicide among Sámi as “Sámi suicides”, possibly meaning that some participants were not familiar with such a narrative or that they meant it was not appropriate to talk about it in that way. The category is mentioned here in the interest of transparency but is not discussed in the following.

Table 2.

Results including number of excerpts, categories and themes

| Number of excerpts | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Discrimination against Sámi | Sámi are treated negatively by the majority society |

| 2 | Prejudices against Sámi | |

| 5 | Not everyone experience negative treatment | |

| 16 | Bullying against Sámi | |

| 10 | Structural discrimination against Sámi | |

| 13 | Consequences of negative treatment | |

| 5 | Lack of knowledge about Sámi and Sámi contexts | |

| 29 | Reindeer herders face much negative treatment | |

| 14 | Inherited family stigma | Some Sámi face negative treatment from other Sámi |

| 8 | To not have strong enough Sámi identity is a problem | |

| 5 | Individuals facing more negative treatment struggle | |

| 4 | Having visited psychiatric hospital stigmatises | |

| 16 | Mental illness as a stigma for the individual | |

| 7 | Deviant sexuality might lead to social exclusion | |

| 5 | Loss of culture |

The historic losses of the Sámi has turned into a void |

| 2 | Loss of religion and spirituality | |

| 3 | Loss of language | |

| 6 | Loss of land and animals | |

| 23 | The negative consequences of the losses of Sámi identity | |

| 2 | Discrimination from the healthcare system |

Sámi are not provided with equal mental health care |

| 8 | Less than perfect equality results in negative consequences | |

| 6 | The boys do not fit into the care system | |

| 7 | Critique against the diagnostic system | |

| 9 | Differences of culture between Norwegian and Sámi patients | |

| 9 | Less trust in Norwegian health care systems | |

| 1 | Health potential in discovering your Sámi identity | |

| 26 | Sámi cultural competence is lacking | |

| 3 | Language competency is lacking | |

| 17 | Problems when asking for help | |

| 22 | Everyone helps out after a suicide | The Sámi networks have significance |

| 21 | The Laestadianism movement protects health | |

| 19 | The social networks supports in times of crisis | |

| 17 | Relationships with other Sámi protects identity, which protects health | |

| 16 | The disadvantages of keeping together as Sámi | |

| 21 | Extended family protects health | |

| 6 | Failed individual problem solution | Birgetkultuvvra might be a problem |

| 7 | Impacts of traditional and non-traditional childrearing | |

| 5 | They showed no signs of suicidality | |

| 13 | One should not talk about or show (negative) feelings | |

| 14 | It is mostly a boys’ problem | |

| 5 | Pressure to perform perfect | |

| 6 | Signs were not taken seriously | |

| 4 | There is no room for being a failure | |

| 10 | Honour means to manage yourself and not lose face | |

| 7 | Critiquing Sámi suicides |

Findings are presented thematically and illustrated with quotes, using a code of letters and numbers to specify individual participants (letters A–E referring to which FGD the specified participant belonged to).

Sámi are treated negatively by the majority society

Participants connected suicide among Sámi to Sámi experiencing negative treatment, ethnic discrimination and racism, including; prejudices and bullying against Sámi, and structural discrimination. Examples of negative treatment included (intentional) use of derogatory terms such as “damn Sámigirl”, but also non-intentional effects of non-Sámi making jokes about their Sámi peers lacking stereotypical attributes of “Sáminess”. This was described by one participant reflecting on how a seemingly friendly joke could be perceived as emotional violence:

C1: ’Where are your komager [traditional pointy shoes]?’ – of course it was a joke and not seriously meant all the time, but when we hear it a hundred times, a thousand times, it becomes more than a joke

Even though it was also stressed that not all Sámi necessarily experience such negative events, those who did expressed frustration and felt it drained their energy and coping abilities. An example of this was a participant struggling with taking pride in her Sámi identity due to both non-intentional, but harmful, lack of knowledge, and bullying of her as a Sámi:

D4: You give up!/…/They wonder if I live in a lávvu [traditional Sámi tent for nomadic lifestyle] and whether we have chiefs/…/It’s difficult being proud when they laugh at you

The negative treatment was understood as creating a context wherein Sámi face systemic emotional violence, especially when officials (including health care personnel) treated Sámi like that. This was especially highlighted in relation to reindeer herding Sámi and their families, who are often regarded as “more authentic” carriers of traditional Sámi culture were described as suffering from more negative treatment than other Sámi.

Experiencing this kind of negative treatment, and the resulting feelings of shame and anger, was described as a life burden connected to suicide among Sámi.

Some Sámi face negative treatment from other Sámi

Another theme in the discussions was an understanding that some Sámi face both negative treatment from the majority society as well as being socially excluded, or not fully accepted, within the Sámi society. For example, this included Sámi without “strong enough” Sámi identity, being part of a family with a bad reputation (family stigma), being regarded as a person who was mentally ill or had “been to the madhouse” (psychiatric facilities), or not conforming to the norm of heterosexuality. Even though being subjected to more negative treatment than other Sámi (because of a double stigma) was regarded as bad indeed, being denied a rightful place within the Sámi society was said to be even worse. In this way, the negative treatment of Sámi from other Sámi was not only understood as related to suicide through increasing “the burden of being a Sámi”, but also through denial of access to a place of safety and shelter from negative treatment.

A2: We all know [about] feelings of being different within Norwegian society. But I thought about if you´re different in one way or another within the Sámi society, it must be ten times harder, that is – if you feel different there

The historic losses of the Sámi have turned into a void

The discussions highlighted how Sámi identity and health was experienced as negatively affected by historical processes where Sámi have suffered losses of culture (such as traditional knowledge, religion, language and relationship with nature and animals).

C1: The [Sámi] society has had a long, long period of oppression, of course it weighs in, it makes the burden heavier, I think

Stories shared included being scolded in school for speaking Sámi, not learning traditional knowledge because it was replaced by other curricula in school, and how modern lifestyles and exploitations of land and water had led to Sámi experiencing weakened bonds with nature, animals, older generations and ancestors. These losses were related to feelings of worthlessness, homelessness, being ashamed, wanting to give up and feeling empty; “like within a void”. A group discussed what emptiness meant in this case:

E1: You feel kind of worthless, small in this world. Because there´s no belonging no matter where you turn. Not looking back in time, nor ahead.

E4: Yes, it is really that sense of belonging.

E1: I mean you become worthless, plain and simple.

Interviewer: Who do you become then?

E1: Yes, who do you become then? Then you are not so careful anymore.

E2: You become kind of homeless.

E1: Homeless, yes, helpless.

In this way they described how Sámi had lost meaningful sociocultural belongings and connections, and how the appurtenant experiences of existential homelessness, psychological worthlessness, and helplessness may contribute to suicide.

Sámi are not provided with equal mental health care

The discussions emphasised lack of equal mental health care for Sámi, and how this can contribute to suicide. It was said that Sámi often have less trust in the (Norwegian) health care system because of perceived shortcomings of the system. The main reasons stated for this was lack of culture and language competencies among health care professionals, resulting in bad or postponed treatment due to the clinician having to learn so much about Sámi cultures and context – often from the Sámi patient – before being able to proceed to treatment:

D3: If you are Sámi and you enter a Norwegian health care system and have to explain your situation, then you’re faced with so much folly

However, some participants also shared stories of being directly, sometimes intentionally, badly treated or discriminated against by health care personnel, because of their Sámi identity. Furthermore, the very organisation of services was said to be more negative for Sámi patients than others due to Sámi cultures and norms not being reflected in service delivery. These negative experiences of, and attitudes towards, mental health care was said to prevent Sámi people from seeking help for their suicidality, thereby implying the lack of equal mental health care as an issue related to suicide among Sámi.

D4: I do not want to seek help/…/I think that If I should have sought out help/…/what will I encounter, like? Because I can’t stand it, that becomes more of a struggle for me then to just keep on carrying the load by myself.

The strong Sámi networks have both positive and negative impacts

The significance of family and other interpersonal relationships within the Sámi community was expressed continuously during the discussions, especially in relation to strengthening of health, resilience and recovery in face of suicide. The bonds within the Sámi society were described as a positive, strong and intrinsic network of relationships. The extended Sámi family was described as very important in terms of upbringing and socialisation to norms. However, the strong relationships within the network caused profound impacts when someone died of suicide:

A5: You identify at once/…/you almost know the family to some, you always know someone who knows [them], that’s how it is

Much like with family, in communities where the laestadianism movement [a pietistic movement within the protestant churches in northern Scandinavia] is strong the participants also mentioned the congregation as an important source of resilience. All these networks were described as functioning like helpers after suicide, managing the crisis for those most bereaved; helping with everything from money, cleaning and all sorts of practical things, and also someone to talk to and just keep you company. This was described as the Sámi way, or “how we do it”:

A2: You visit these houses, you are there with them, you go straight into that nuclear family and you talk to people. And you stay there, make coffee, and in a way, you just “spin around” there to a great extent

It was also said that the strong sense of family and community could have negative side effects; that it could lead to families not wanting to seek help from outsiders (i.e. mental health services) to deal with suicidality due to the risk of the whole family being labelled – stigmatised – with a bad reputation.

“Birgetkultuvvra” might be a problem

Birgetkultuvvra; the “hardening” and ideal of “ieš birget” [to manage by yourself] in the Sámi way of bringing up children was problematised. Some meant that decline of traditional upbringing styles might lead to parents not preparing their children enough for the harsh reality that awaits them as adults. However, others related such upbringing styles to prevailing ideals (especially among boys) of not showing weakness, talking about negative feelings or asking for help. Furthermore, such ideals were connected to people who had killed themselves through those individuals often being described as persons who did not communicate their distress, or ask for help:

E1: I have thought about shame and guilt and I have thought that those things are hard to talk about, it is something that we hide away within ourselves. It is kind of like this: you are not strong if you talk about suicide, you are not strong then, in a sense, you are weak then.

It seemed that this issue came down to the importance of not losing face, that you should be regarded as a perfect person without mental problems, who belonged in the Sámi world and had (his) honour intact. Some participants also pointed to a possibility that such meanings could be so embedded in culture that they were almost rendered “invisible”, but could be stated like this:

E3: If you do not birget [manage] then you don’t belong here/…/if you’re good for nothing you might as well die

Discussion

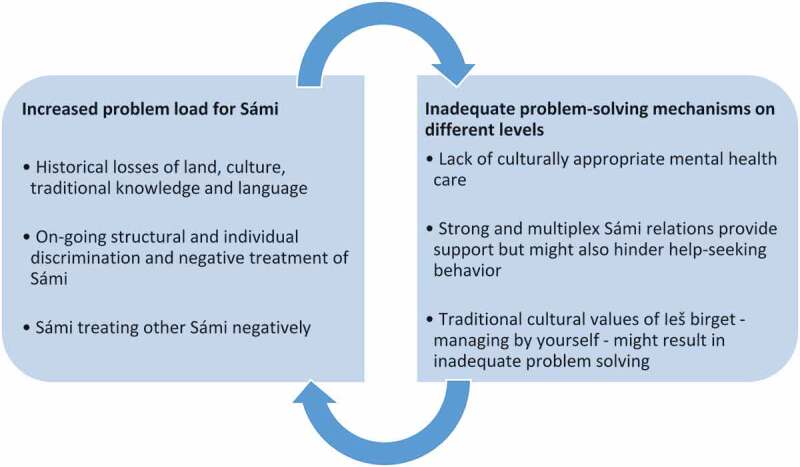

The aim of this study was to utilise FGDs to explore and understand cultural meanings of suicide among Sámi in Norway. In the following, the findings are contextualised and discussed in relation to previous research and the present Sámi context. In the discussion, the six themes are organised in two broad frames of understanding; increased problem load for Sámi and inadequate problem-solving mechanisms on different levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visual model of results

Increased problem load for Sámi

The participants highlighted ways in which life might be more difficult for Sámi than the majority population, implying that increased problem load is related to suicide among Sámi. Issues discussed included discrimination against Sámi, and Sámi treating other Sámi negatively, but also how Sámi’s historical losses of land, culture, traditional knowledge and language(s), might lead to Sámi struggling with their identity (as Sámi); becoming “empty” or “homeless”. Some of these issues, especially discrimination, have been well documented in research. Experiencing oneself as discriminated is ten times more common among Sámi than (majority) Norwegians [32], and those who report this are more likely to also report worse health [33,34]. Furthermore, Omma et al. [10] found that young adult Sámi on the Swedish side of Sápmi experiencing themselves as discriminated against, also reported significantly more suicidality [10]. In addition, Eriksen et al. [35] found that Sámi in Norway reported being subjected to more emotional, physical and sexual violence than majority Norwegians, both growing up and as adults. However, it is unknown if, and to what extent, these issues are attributed to negative treatment and violence from other Sámi. Actually, both historical losses (in relation to health) and Sámi treating other Sámi negatively are understudied in Sápmi [36]. One may also note that concepts such as lateral violence (which in this case would refer to violence between Sámi), historical trauma and racism seldom have been used to shed light on these issues in the Sámi context [36].

Inadequate problem-solving mechanisms on different levels

The findings highlighted several themes that could be said to address the issue of inadequate problem solving for suicidal persons as central to suicide among Sámi. For example, Sámi in Norway are entitled to equal mental health care services, but participants maintained that shortcomings in the health system were structural and included lack of language competency, lack of culturally adapted services and prejudiced health care personnel. This is well known, and research has confirmed that Sámi patients are more dissatisfied than the majority population with primary health care [37], that use of Sámi language in the Norwegian health system is complicated (even when language competency is available) [38,39] and that ethnic matching in client – therapist relations (Sámi-Sámi, Norwegian-Norwegian) might have positive treatment effects in psychiatry [40], implying that cultural competence is beneficial.

The impacts of the strong and multiplex network relations within the Sámi world was discussed in the FGDs, as it was among Sámi in Sweden, too [24]. Similar to the Swedish study, our findings included both positive and negative aspects, including how the networks are activated after a suicide, with people coming together and supporting the bereaved. Other researchers have also noted the importance extended family networks has in caring for the sick or vulnerable among Sámi [41]. However, some participants in this study shared their fear of an opposite effect, namely that suicidal individuals would not want to seek help because of fear that it would lead to social exclusion of themselves, or their families, if others knew about their distress.

Boine [42] and Javo et al. [43] have shown that Sámi parents emphasise that their children, especially their boys, learn to be autonomous and self-reliant. Participants in this study discussed and criticised such traditional values of “ieš birget” – in northern Sámi meaning: “to manage by yourself” – which they meant could contribute to suicide among Sámi. One participant connected this to a sort of fatalistic “undercurrent” in society, a norm perhaps, which could be verbalised: “if you can’t birget [manage], then you don’t belong here” or “if you are good for nothing you might as well die.” As culture should serve as a vehicle to pass on adaptation capabilities, this can perhaps indicate that the traditional value of “ieš birget” might have become dysfunctional in the modern day context. In other words: values like “ieš birget” may be beneficial in many ways, certainly in traditional societies with harsh climate and few resources, but concern was shared that being too self-reliant and independent might be a trap in the modern world, where a more relational problem-solving strategy, such as asking other’s for help, would be more adaptive. Findings like these are not unique, as researchers focusing on the role of masculinity in suicide have argued that similar values underpinned suicidal actions in other contexts, for example among young men in Norway [44] and men in Australia [45].

New frameworks for understanding health and suicide in the Sámi context

Clark et al. [46] have described how the use and understanding of the term “lateral violence” among aboriginal Australians in the Melbourne area might lead to social change, proposing that changing the way we understand health phenomenon holds the power to reframe it in a way that makes it possible to take action. Similarly, disparities in health that otherwise might be considered a stigma for Sámi might be easier to talk about and study if the framework for addressing those disparities is changed. For example, in a 2015 debate following the publication of a series of newspaper articles on sexual abuse in a small Lule Sámi community [47], Kalstad Mikkelsen [48] framed the sexual violence in her home community in terms of “lateral violence”. She maintains that the historical, and on-going oppression and discrimination of Sámi has led to them feeling ashamed, and that it is this shame that might result in sexualised violence against other Sámi. Furthermore, she argues that understanding these links is key to successfully addressing the issue inside the community itself. Similarities between Kalstad Mikkelsen and findings in this study are apparent, as when participants referred to historical and on-going discrimination and oppression of Sámi resulting in Sámi feeling empty, homeless, “like within a void”; in the end describing it as a factor in suicide among Sámi.

It is important to relate to these frameworks of understanding, for example lateral violence and historical trauma influencing suicidality among Sámi, when designing health interventions in the Sámi context. For example, if empowering Sámi identities is considered key among Sámi themselves both in suicide prevention and addressing sexual violence among Sámi, an intervention that fails to acknowledge this might be seen as stigmatising Sámi further; hence increasing the likelihood that the intervention will have small, or opposite, effects.

Strengths and limitations

This study is based on data from focus group discussions with 20 Sámi, and 2 non-Sámi participants, and we cannot know to what extent the participants’ understanding of suicide among Sámi are representative for all Sámi in Norway. However, in qualitative research it is not the intention to generalise findings to the whole population, but rather to gain deeper insight into the phenomenon of study. We argue that the open-ended dialogues and the cultural safety provided through the procedure and context of FGDs fostered honest and reflective conversations that support the credibility and overall trustworthiness of the study [49]. Utilising the snow-ball method strengthened the credibility since we were able to include members of the Sámi communities that other members held in high esteem and saw as knowledgeable for the purpose of the study. In addition, we put together focus groups that were diverse in terms of backgrounds, in order to bring many perspectives into the discussions and create FGDs where participants felt safe enough to speak openly about this highly sensitive topic (including voicing critique, which some did). The credibility of the study was also strengthened by continuous discussion of findings between researchers with different personal and academic backgrounds, ensuring that interpretations were reasonable.

The dependability and transferability of the study is hard to assess since socio-cultural meanings shift naturally over time and contexts. The open-ended design also limits dependability in itself. However, the similarity and overlap in themes between this study and the previous one, among Sámi in Sweden [24], is an argument for at least some dependability and transferability of findings. Transferability beyond this, such as to other Sámi and Indigenous contexts in the western world, should be done cautiously and not without profound insight into the relevant context.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that the participants understand suicide among Sámi as connected to historical, contextual and cultural issues including historical and on-going oppression of Sámi, negative treatment of Sámi by other Sámi, a lack of problem solving mechanisms on different levels including; shortage of relevant and culturally safe mental health care, issues connected to the complexity and strength of Sámi networks, as well as traditional cultural values supporting “managing by yourself” rather than employing relational problem solving strategies. The findings are relevant for development of suicide prevention strategies in the Sámi context in Norway.

Acknowledgements

We give thanks to the participants of this study, who generously shared their thoughts with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- [1].Young TK, Revich B, Soininen L.. Suicide in circumpolar regions: an introduction and overview. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Herne MA, Bartholomew ML, Weahkee RL.. Suicide mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):336–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chachamovich E, Kirmayer LJ, Haggarty JM, et al. Suicide among inuit: results from a large, epidemiologically representative follow-back study in Nunavut. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(6):268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bjerregaard P, Viskum Lytken LC. Time trend by region of suicides and suicidal thoughts among Greenland inuit. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:26053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sumarokov YA, Brenn T, Kudryavtsev AV, et al. Suicides in the indigenous and non-indigenous populations in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Northwestern Russia, and associated socio-demographic characteristics. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2014;73:24308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Silviken A, Haldorsen T, Kvernmo S. Suicide among indigenous Sami in arctic Norway, 1970–1998. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(9):707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hassler S, Johansson R, Sjolander P, et al. Causes of death in the Sami population of Sweden, 1961–2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(3):623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Soininen L, Pukkola E. Mortality of the Sami in northern Finland 1979–2005. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(1):43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kaiser N, Salander Renberg E. Suicidal expressions among the Swedish reindeer-herding Sami population. Suicidol Online. 2012;3:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Omma L, Sandlund M, Jacobsson L. Suicidal expressions in young Swedish Sami, a cross-sectional study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:19862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Minde H. Assimilation of the Sami-implementation and consequences. J Indigenous Peoples Rights. 2005;3. [Google Scholar]

- [12].The government of Norway The Sami people. 2018. cited 2018 September17 Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/indigenous-peoples-and-minorities/Sami-people/id1403/

- [13].Hjelmeland H, Knizek BL. Suicide and mental disorders: a discourse of politics, power, and vested interests. Death Stud. 2017;41(8):481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hjelmeland H. Cultural context is crucial in suicide research and prevention. J Crisis Intervention Suicide Prev. 2011;32(2):61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hjelmeland H, Knizek BL. Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(1):74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Katz LY, Elias B, O’Neil J, et al. Aboriginal suicidal behaviour research: from risk factors to culturally-sensitive interventions. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(4):159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kirmayer L, Brass G, Holton T, et al. Suicide among aboriginal people in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marsella AJ, Dubanoski J, Hamada WC, et al. The measurement of personality across cultures: historical, conceptual, and methodological issues and considerations. Am Behav Sci. 2000;44(1):41–62. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Andoh-Arthur J, Knizek BL, Osafo J, et al. Suicide among men in Ghana: the burden of masculinity. Death Stud. 2018;42(10):658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Colucci E. “Focus groups can be fun”: the use of activity-oriented questions in focus group discussions. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1422–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Roen K, Scourfield J, McDermott E. Making sense of suicide: a discourse analysis of young people’s talk about suicidal subjecthood. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2089–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wexler L. Identifying colonial discourses in Inupiat young people’s narratives as a way to understand the no future of Inupiat youth suicide. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2009;16(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wexler L. Inupiat youth suicide and culture loss: changing community conversations for prevention. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(11):2938–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stoor JPA, Kaiser N, Jacobsson L, et al. “We are like lemmings”: making sense of the cultural meaning(s) of suicide among the indigenous Sami in Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sámi Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Saami Council Plan for suicide prevention among the Sámi people on Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Karasjok, Norway; Sámi Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Redvers J, Bjerregaard P, Eriksen H, et al. A scoping review of Indigenous suicide prevention in circumpolar regions. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:27509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy. Ottawa, Canada: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hansen AM, Virginia RA, Tepecik Dis A, et al. Community Wellbeing and Infrastructure in the Arctic. Aalborg University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [29].World Medical Association World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Strøm KS, Bull K, Broderstad AR, et al. Proposal for ethical guidelines for Sámi health research and research on Sámi human biological material. Karasjok, Norway: Sámediggi/Sámi Parliament of Norway; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hansen KL, Melhus M, Høgmo A, et al. Ethnic discrimination and bullying in the Sami and non-sami populations in Norway: the SAMINOR study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(1):97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hansen KL. Ethnic discrimination and health: the relationship between experienced ethnic discrimination and multiple health domains in Norway’s rural Sami population. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:25125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hansen KL, Sørlie T. Ethnic discrimination and psychological distress: a study of Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012;49(1):26–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Eriksen AM, Hansen KL, Javo C, et al. Emotional, physical and sexual violence among Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway: the SAMINOR 2 questionnaire study. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(6):588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stoor JPA. Kunskapssammanställning om psykosocial ohälsa bland samer [Compilation of knowledge on psychosocial health among Sámi]. Kiruna, Sweden: Sametinget/Sámi Parliament of Sweden; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nystad T, Melhus M, Lund E. Sami speakers are less satisfied with general practitioners’ services. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(1):114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dagsvold I, Møllersen S, Stordahl V. What can we talk about, in which language, in what way and with whom? Sami patients’ experiences of language choice and cultural norms in mental health treatment. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74(1):26952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dagsvold I, Møllersen S, Stordahl V. “You never know who are Sami or speak Sami” Clinicians’ experiences with language-appropriate care to Sami-speaking patients in outpatient mental health clinics in Northern Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75:32588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Møllersen S, Sexton HC, Holte A. Effects of client and therapist ethnicity and ethnic matching: a prospective naturalistic study of outpatient mental health treatment in Northern Norway. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(3):246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Langås-Larsen A, Salamonsen A, Kristoffersen AE, et al. ”We own the illness”: a qualitative study of networks in two communities with mixed ethnicity in Northern Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1438572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Boine EM. Ii gii ge ollesolmmoš ge liiko jus gii nu livče nu čuru das birra jorramin - Selv ingen voksne hadde likt at noen surret rundt der som en flue. Verdioverføring fra far til sønn - i en samisk kontekst [No grown-up would have liked if someone buzzed around them like a fly. Transferring values from father to son – in a Sámi context] In: Hauan MA, editor. Maskuliniteter i Nord. KVINNFORSKs skriftserie Senter for kvinne- og kjønnsforskning. Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø, Norwegian; 2007. p. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Javo C, Alapack R, Heyerdahl S, et al. Parental values and ethnic identity in indigenous Sami families: a qualitative study. Fam Process. 2003;42(1):151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rasmussen ML, Haavind H, Dieserud G. Young men, masculinities, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2018;22(2):327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].River J. Suicide and hegemonic masculinity in Australian men. Illions (IL): Charles C. Thomas Springfield; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Clark Y, Augoustinos M, Malin M. Lateral violence within the aboriginal community in Adelaide: “it affects our identity and wellbeing”. J Indig Wellbeing. 2016;1(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Berglund EL, Henrikssen TH, Amdal H, et al. Den mørke hemmeligheten [The Dark Secret]. VG. 2016. cited 2018 March19 Available from: https://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/tysfjord-saken/den-moerke-hemmeligheten/a/23706284/Norwegian

- [48].Kalstad Mikkelsen A. Taushet, tabuer og tapte ansikter - angår det oss? [Silence, taboos and people loosing face - does it concern us?]. Bårjås. 2016;(1):46–58. Norwegian. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]