Abstract

Objectives:

The interactivity of proanthocyanidins (PACs) with collagen modulates dentin matrix biomechanics and biostability. Herein, PAC extracts selected based on structural diversity were investigated to determine key PAC features driving sustained effects on dentin matrices over a period of 18 months.

Methods:

The chemical profiles of PAC-rich plant sources, Pinus massoniana (PM), Cinnamomum verum (CV), Hamamelis virginiana (HV) barks, and Vitis vinifera (VV) seeds, were obtained by diol UHPLC analysis after partitioning of the extracts between methyl acetate and water. Dentin matrices (n = 15) were prepared from human molars to determine the apparent modulus of elasticity over 18 months of aging. Susceptibility of the dentin matrix to degradation by endogenous and exogenous proteases was determined by presence of solubilized collagen in supernatant, and resistance to degradation by bacterial collagenase, respectively. Data were analyzed using ANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc tests (α=0.05).

Results:

After 18 months, dentin matrices modified by PM and CV extracts, containing only non-galloylated PACs, were highly stable mechanically (p<0.05). Dentin matrices treated with CV exhibited the lowest degradation by bacterial collagenase after 1 hr and 18 months of aging (p<0.05), while dentin matrices treated with PM showed the least mass loss and collagen solubilization by endogenous enzymes over time (p<0.05).

Significance:

Resistance against long-term degradation was observed for all experimental groups; however, the most potent and long-lasting dentin biomodification resulted from non-galloylated PACs.

1. Introduction

Adhesive resin restorative therapies are widely used to replace decayed and lost hard tissue structures of teeth. Dentin, the bulk component of teeth, retains type I collagen-rich organic phase, an essential anchoring component of resin-based restorative materials [1]. However, enzymatic and hydrolytic collagen degradation destabilize the complex dentin-resin interface, thereby increasing susceptibility to secondary caries, which is a major reason of failure of resin-based restorations [2].

Introducing exogenous collagen cross-links by treatment with plant-based proanthocyanidins (PACs) is a biomimetic strategy to modify the dentin extracellular matrix and improve the stability of the resin-dentin interface [3]. The effectiveness of PACs depends on their ability to engage in hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and covalent interactions that mediate collagen cross-linking at intra-molecular and inter-microfibrillar levels [4]. Exploratory studies showed that plant sources rich in PACs improve the physicochemical properties of the dentin matrix [4–6].

In addition to the mechanical enhancement of the dentin matrix, there is considerable evidence for the direct effect of PACs in the inactivation of key endogenous dentin proteases [4,7] involved in caries progression and degradation of the dentin-resin interface [8,9]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [10, 11] are compromising the stability of collagen at the dentin-resin interface and, thus, can shorten the service-life of resin composite restorations [12]. Inhibition of dentin matrix degradation by crude PAC-rich extracts and isolated PACs were observed using recombinant and native matrix metalloproteases and cathepsins [13] as well as aggressive enzymatic models with bacterial collagenase [14, 15]. Mass loss and detection of collagen specific hydroxyproline amino acid in storage media provide are valuable methods to study biostability of type I collagen in dentin matrices [5, 6, 12,].

The sustainability of the PACs-dentin matrix interactions is key for successful clinical application. Distinctive chemical features in biosynthesized PACs may hold important clues to the sustained interactivity with the dentin matrix components. Studies of isolated compounds and crude extracts point to key chemical structural features of PACs on their specific dentin bioactivity [3–6]. Particular structural motifs are prevalent in certain plant species (Table 1). Evaluation of the sustained, long-term activity of PACs can guide the selection source of renewable resources which are specialized in the biosynthesis of PACs that elicit long-lasting dentin activity and will ultimately help in the discovery of new lead structures.

Table 1.

Overview of primary phytochemical components in pine bark, grape seed, cinnamon bark, and witch hazel extracts.

| Source | Type of tannins | Interflavan linkage (IFL) | Major constituent monomers | Known major compounds and distinctive PAC characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus Massoniana (PM) bark | Condensed (procyanidins) | A type, mixed A-B type | catechin, epicatechin | procyanidin A1, A2; higher polymeric PAC content relative to CV |

| Cinnamomum Verum (CV) bark | cinnamaldehyde, procyanidin A1, A2, cinnamatannin B1; enriched in trimers and tetramers relative to PM, VV and HV | |||

| Vitis vinifera (VV) seed | Condensed (Procyanidins, prodelphinidins, including galloylated congeners) | B-type | catechin, epicatechin epigallocatechin, gallocatechin | procyanidins B1, B2, C1; highest polymeric PAC content relative to PM, CV and HV |

| Hamamelis Virginiana (HV) bark | Condensed (Procyanidins, prodelphinidins) and hydrolyzable | B-type; ester linkage between sugar core and gallic acid moieties | catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, gallocatechin, gallic acid | hamamelitannin, pentagalloyl glucose |

Covering a period of 18 months, this study assessed dentin matrices that were modified by PACs from four distinct natural sources, all of which are rich in these polyphenols, but differ not only in their actual PAC content but also in their degree of polymerization (DP) and other parameters of structural diversity. The overarching hypothesis tested was that predominant structural features such as galloylation and interflavan linkages are key to the durability of permanent physicochemical modification of dentin matrices.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Plant Extracts Selection and Chemical Profiling

Extracts known to be rich sources of proanthocyanidins (PACs) were obtained from the following plants species: seeds of grapes, Vitis vinifera L. cf. (Polyphenolics MegaNatural Gold Grape Seed Extract, Madera, California, USA, No. 206112508–01/122112505–01); stem bark of true cinnamon, Cinnamomum verum J. Presl. (Oregon’s Wild Harvest, Sandy, Oregon, USA, No. CIN-07011p-OMH01); the inner bark of Pinus massoniana Lamb. (Xi’an Chukang Biotechnology Co. Ltd., China, No. PB120212). Raw material of witch hazel bark (Hamamelis virginiana L.) was obtained from Mountain Rose Herbs Inc. (Eugene, OR, USA) and prepared in house using 70 % acetone extraction. The PACs-rich crude extracts are represented by abbreviations as follows: Pinus massoniana (PM), Cinnamomum verum (CV), Hamamelis virginiana (HV), and Vitis vinifera (VV).

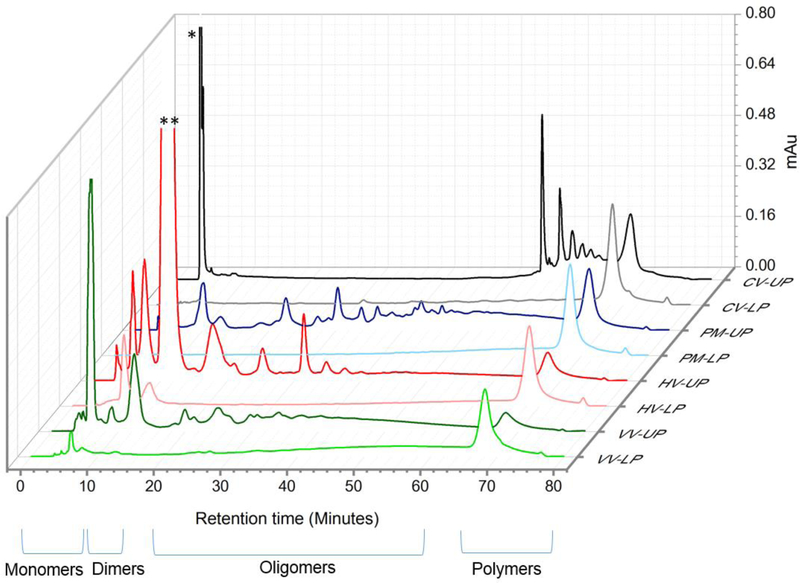

The chromatographic profiles of crude extracts are complex and difficult to interpret due to the abundance of polymeric PACs. Thus, all extracts were subjected to water/methyl acetate partitioning, whereby most of the polymeric PACs were concentrated in the LP enabling the interpretation of UP chromatograms (Figure 1). Both the methyl acetate (Upper Phase-UP) and water (lower phase-LP) partitions were dried in a speed vacuum dryer. The UP and LP samples were dissolved in 1.5 ml and 2.5 ml 70 % methanol respectively and filtered prior to injection. Acetonitrile/acetic acid (98/2) was solvent A, and methanol/water/acetic acid (95/3/2) was solvent B. The HPLC analysis was performed according to a method previously reported in the literature [18] using the Develosil 5 μm Diol 100A 250 × 4.6 mm column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, US). The extracted chromatograms (280 nm) were stacked using the Empower data software from Waters 600 HPLC (Figure 1). Table 1 contains a description of the main constituents of each extract.

Figure 1.

Stacked Diol HPLC-UV profiles of methyl acetate/ water partitions of crude extracts. Pinus massoniana (PM), Cinnamomum verum (CV), Hamamelis virginiana (HV) and Vitis vinifera (VV). UP – upper phase; LP – lower phase. The chromatograms were stacked in OriginPro using Waterfall Z:color plot; * cinnamaldehyde; ** Hamamelitannin. Compounds (UV peaks) eluting with an increasing retention time indicate an increasing degree of polymerization (DP). The diol stationary phase is especially utilized to separate the extracts according to their DP. Each UV peak represents several PACs with the same DP grouped together.

2.2. Dentin Preparation and Biomodification

Fifty-two extracted sound human molars were selected following an approval by the Institutional Review Board Committee of the University of Illinois at Chicago (protocol No. 2011–0312). A total of 225 dentin specimens (1.7 × 0.5 × 6.0 mm) were obtained and fully demineralized in 10% H3PO4 (Ricca Chemical Company, Arlington, Texas, US) for 5 h, as previously described [5]. The treatment solutions were prepared at 0.65% and 6.5% w/v, by dissolving each extract in buffer solution (0.02 M HEPES), except for CV which was dissolved in an ethanol:buffer mixture (ratio 50:50) to increase PAC solubility. All treatment solutions had pH adjusted to 7.2. Dentin specimens were randomly divided into 9 groups (n = 15, totaling 135 specimens), immersed in 100 μL of treatment solutions for 1 h, at room temperature under stirring. Specimens corresponding to control group were immersed in 0.02 M HEPES buffer for the same time.

2.3. Mechanical studies of the dentin matrix

The apparent modulus of elasticity was determined in a three-point bending flexural test with a 1 N load cell on a universal testing machine (EZ Graph, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min [5]. The specimens were immersed in distilled water using a custom submersion three-point bending fixture. The demineralized dentin beams (n = 15) were assessed at baseline and after one hour of treatment in the respective solutions. Specimens were then stored individually in 2 mL simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C, which was collected every 2 weeks and replaced with fresh SBF. The modulus of elasticity was assessed at 1-h, 3-month, 9-month, 12-month, and 18-month time points. SBF consisted of 50 mM HEPES, 5 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 0.001 mM ZnCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 3 mM, 154 mM NaN3 at pH 7.4. The apparent modulus of elasticity was calculated as previously described [5]. Data were statistically analyzed using 2-way ANOVA, followed by Games-Howell post hoc test (α = 0.05).

2.4. Biodegradation of the Dentin Matrix by Endogenous Proteases

Collagen solubilization was quantified by the release of hydroxyproline (Hyp) into the storage media (SBF) throughout the 18 months of aging. Sodium azide was used in the SBF to inhibit bacterial growth, thus the presence of Hyp is attributed to the activity of tissue-derived enzymes. The SBF was collected and pooled individually (n = 15 per group) into five periods: 1–3 months, 3–6 months, 6–12 months, and 12–18 months. The pooled media from each specimen was lyophilized and resuspended in 0.2 mL deionized water. The Hyp assay followed a standard protocol with modifications [16]. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm in a spectrophotometer (Spectramax Plus, Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, CA, US). Standard curve using various Hyp concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ug/mL) were generated using 1 ug/mL OH-L-proline. Data were statistically analyzed using 2-way ANOVA and Games-Howell post hoc test (α = 0.05).

2.5. Biodegradation of the Dentin Matrix by Exogenous Protease

After 18 months of aging in SBF, the dentin specimens were individually dried and weighted (M1). Additional dentin specimens (n = 15, totaling 90 specimens) were freshly prepared to evaluate the resistance against enzymatic degradation immediately following dentin matrix treatment (24 h). The treatment protocol (section 2.2) described above was repeated and the dry mass was collected (M1). Following re-hydration, all specimens were immersed in 2 mL of digestion medium containing bacterial collagenase (100 μg/mL Clostridium histolyticum; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, US) in 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.9) for 24 h at 37°C [5]. Following, specimens were kept in a desiccator for 24 h and individually weighted after exposure to collagenase (M2). The percentage of biodegradation (R) was calculated as follows: R (%) = 100 − ((M2 × 100) / M1), where M1 is the dry mass of specimens after biomodification, and M2 is the mass after bacterial collagenase digestion. Data were statistically analyzed using 2-way ANOVA, followed by Games-Howell post hoc test (α = 0.05).

3. Results

The apparent modulus of elasticity of experimental groups are shown in Table 2. All time-points showed a significant increase in the modulus of elasticity after biomodification of dentin matrices with any of the PAC-rich intervention materials, when compared to control (p < 0.001). Statistically significant differences were also observed between concentration groups as follows: 6.5%: PM=VV=CV>HV>Control; and 0.65%: PM>VV=CV=HV>Control (p < 0.001). Among the various PAC sources, HV exhibited the lowest increase to the modulus of elasticity of dentin (p<0.001). The highest increase was observed for groups treated with PACs solutions prepared at 6.5% w/v (p < 0.001). However, for these treatment groups, a lower stability of the modulus of elasticity was also observed (p < 0.001). Dentin matrices treated with 0.65% PM and VV remained stable after 18 months (p > 0.05). Interestingly, an increase in the mechanical properties occurred for both CV and HV in the first 3 months, conversely only for CV the enhancement in modulus of elasticity was permanent, whereas for HV a significant drop in the modulus of elasticity was observed after 18 months, resulting in the lowest values among all PAC-treatment groups (p < 0.001). However, the modulus of elasticity of the 0.65% HV group remained statistically higher than that of the control group after 18 months of aging (p <0.001).

Table 2.

Long-term evaluation of the apparent modulus of elasticity of the dentin matrix treated with proanthocyanidins sources with distinct phytochemistry.

| Apparent Modulus of Elasticity of the Dentin Matrix [Mean(SD)] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source * | Concentration δ |

Incubation time in SBF | ||||

| Immediate | 3 months |

9 months |

12 months |

18 months |

||

| Pinus massoniana (PM) | 6.5% | 56.51a (10.37) |

50.16 ab (8.83) |

45.80 a (9.43) |

46.48 ab (10.20) |

42.09 b (9.29) |

| 0.65% | 28.22 a (4.26) |

29.37 a (6.32) |

26.72 a (4.80) |

26.89 a (7.03) |

24.49 a (6.34) |

|

| Vitis vinifera (VV) | 6.5% | 60.01 a (12.97) |

46.75 ab (12.39) |

43.91 b (11.93) |

43.39 b (11.53) |

23.91 c (3.73) |

| 0.65% | 22.00 a (3.99) |

24.22 a (4.78) |

22.91 a (5.62) |

21.26 a (4.88) |

20.36 a (4.34) |

|

| Cinnamomum verum (CV) | 6.5% | 46.07 a (5.80) |

45.97 a (6.18) |

38.59 bc (3.10) |

42.92 ab (5.29) |

34.36 c (5.86) |

| 0.65% | 15.57 c (4.09) |

26.82 ab (7.13) |

20.47 bc (4.96) |

23.20 ab (6.63) |

20.67 bc (6.41) |

|

| Hamamelis virginiana (HV) | 6.5% | 42.32 a (6.75) |

28.92 b (5.81) |

26.04 b (5.57) |

26.81 b (5.25) |

23.49 b (4.48) |

| 0.65% | 17.66 b (3.58) |

22.58 a (4.40) |

16.45 b (3.50) |

18.26 ab (3.24) |

15.26 b (3.43) |

|

| Control | 8.67 b (1.93) |

11.92 a (3.00) |

9.23 ab (2.55) |

9.27 ab (2.35) |

8.70 b (2.67) |

|

Higher concentrations were significantly higher than lower concentrations of crude sources (p < 0.001).

Statistical significant (p< 0.001) differences among crude sources were concentration dependent as follows: 6.5%: PM=VV=CV>HV>C and 0.65%: PM>VV=CV=HV>C. Different lowercase letters depict statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between storage times for individual extracts and concentrations (comparison made in each row.)

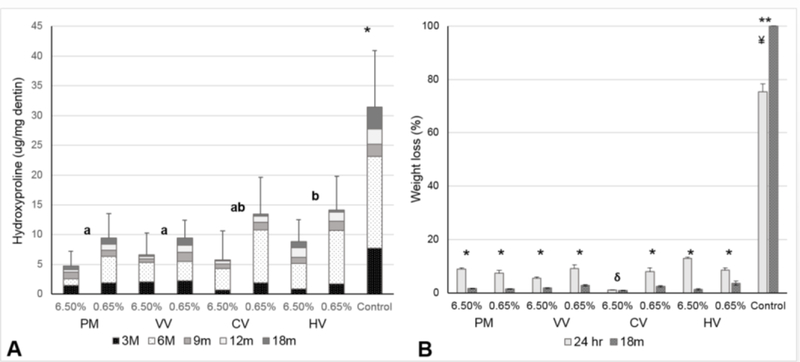

Collagen solubilization analyses revealed significantly lower release of Hyp in groups treated with PACs-rich extracts than the control group after 18 months in SBF (p < 0.001, Figure 2A). There was no significant interactions between type of extract and concentration (p = 0.193). Higher concentrations of extracts resulted in significantly less collagen solubilization, regardless of the source of the PACs (p < 0.001). Statistically significant differences were observed among the PAC sources (p < 0.001), but no differences in HYP detection were observed among PM, VV, and CV. Significantly higher collagen solubilization occurred for HV specimens as compared to all other PAC sources, with the exception of CV.

Figure 2.

Results of the long-term evaluation of dentin matrix degradation via endogenous proteases (A) and exogenous bacterial collagenases (B) upon treatment with proanthocyanidin (PAC) sources with distinct phytochemistry (Pinus massoniana - PM, Cinnamomum verum - CV, Hamamelis virginiana - HV and Vitis vinifera - VV). In A, the * control group exhibited significantly higher degradation than all treatment groups (p < 0.001). Higher concentrations of extracts resulted in significantly increased resistance to degradation for all PAC sources (p < 0.001); statistical differences among sources of PACs is depicted by different letters (p < 0.05). In B, *indicates statistically significant higher resistance to degradation for the treatment groups, whereas **indicates higher degradation of control groups long-term when compared to short term storage (p < 0.001); ¥ indicates that the controls exhibit statistically higher degradation than all other groups (p < 0.05); δ indicates that 6.5% CV treatment exhibits the lowest degradation of all experimental groups (p ≤ 0.004).

Exogenous enzymatically-mediated dentin biodegradation data shows the lowest collagen solubilization for 6.5% CV when compared to all other PAC sources prepared at either 6.5% or 0.65% (p ≤ 0.013, Figure 2B). After 18 months of aging in SBF, a lower mass loss was observed for all PACs groups compared to immediately post-treatment (p<0.001), except for 6.5 % CV treatment (p = 0.251). Conversely, greater dentin matrix biodegradation was observed for the control groups after 18 months (p<0.001, Figure 4). Likewise, after 18 months of aging, the 6.5% CV group showed the least degradation when compared to 0.65% CV, 6.5% PV, and 6.5% VV (p ≤ 0.004).

4. Discussion

This study confirms that the investigated PAC-rich sources exhibit favorable potential for dentin biomodification. Not only the initial potency of the PACs varies based on the outcome measures, but also the sustainability of their achieved biomodification, i.e., the biostability differs. For example, VV and PM were the most potent sources inducing an immediate (post-treatment) enhancement of the dentin matrix modulus of elasticity. In contrast, when biostability played a major role in the assessed biomodification potency, the best results were obtained using PM and CV, both representing extracts that only contained non-galloylated compounds. Between these two groups, the one treated with CV exhibited the greatest short- and long-term biomodification stability against bacterial collagenase (after 1 h and 18 months), while specimens treated with PM showed the least dentin matrix degradation by endogenous proteolytic enzymes after 18 months of aging.

The mechanical properties of dentin treated with high concentration (6.5% wt.) of PM and CV were more stable over time than those treated with VV and HV. The abundance of A-type trimeric PACs in CV and dimeric procyanidin A1 and A-type interflavan linkages (IFLs) in PM are likely contributing the most to the resistance against degradation. This is in line with previous outcomes that demonstrated the greatest protective effect against collagenase degradation with A-type trimeric and dimeric PACs [6]. A-type PACs also exhibit better stability in solutions and lower degradation or oxidation rates. Both CV and PM do not contain gallocatechins (B-ring 3,4,5-trihydroxy substitution) or 3-O-gallates [18], which also is a plausible contribution to the improved stability.

A remarkably high modulus of elasticity was found for the dentin treated with VV at 6.5%. At the monomeric level of catechins, it was shown that galloylated moieties have higher potency to enhance the dentin-collagen cross-linking compared to their non-galloylated counterparts on initial treatment [19] and greater collagen stabilizing effect against bacterial proteolytic degradation [4]. Additionally, it is not only the hydroxy groups that contribute to the cross-linking, but the entire PAC skeleton including the aromatic rings that can lead to hydrophobic interactions.

After 18 months of aging, dentin matrices treated with VV exhibited the highest rate of decrease in the mechanical properties when compared to dentin treated with PM and CV. The following two different mechanisms associated to VV composition may have contributed to the poorer stability of the cross-links: (1) the abundance of B-type PACs in the VV extract, having procyanidin B2 and procyanidin C1 as the most abundant dimer and trimer, respectively; and (2) the presence of galloylated PACs, even though in a smaller ratio, as compared to non-galloylated PACs. It is known that PACs consisting of B-type interflavan linkages are less stable compared to A-type PACs [20]. In addition, galloylated compounds can undergo hydrolysis of the 3-O-gallate ester bonds, a reaction that is thermodynamically likely to occur over time and in water-based solutions. Moreover, higher oxidation/epimerization rates of galloylated PACs [20, 21] could explain the loss in activity of the VV from the initial post-treatment time-point and up to 18 months.

While related molecules with very small size, such as gallic acid itself and its simple derivatives (methyl-gallate, propyl-gallate) show a potential to bind to collagen intramolecularly, mid-molecular weight compounds such as PAC dimers (A1, B1, B2) and higher can diffuse into dentin to interact with collagen in a more efficient manner, at both intermolecular and inter-microfibrillar levels [6]. Despite the fact that small molecules appear to be highly efficient in improving stability of the tissue, small molecules cannot improve the mechanical properties as efficiently and sustainably as their oligomeric analogues. Galloylated PACs can mediate collagen cross-links, however the enhancement in the modulus of elasticity often presents with a significant drop after storage in water-based solutions like SBF. This is likely due to cleavage of the ester bonds in the galloylated PACs, resulting in non-galloylated compounds and gallic acid. This mechanism could explain the observed drop in mechanical properties of the galloylated extracts, which seems to appear without negatively affecting the resistance to biodegradation of the biomodified tissue. Another reason could be the oxidative degradation of B-type PACs, resulting in the formation of higher molecular weight polymeric phlobaphenes or quinones [22, 23], both of which no longer elicit the desired dentin cross-linking interactivity.

Regardless of the applied concentration, HV was the weakest in enhancing the modulus of elasticity of the dentin matrix. However, the dentin biomechanics and the resistance against endogenous and exogenous enzymatic degradation were still greater than control groups. Thus, the overall lower dentin biomodification potency of HV likely arises from the large presence of hydrolysable tannins (80%) and lower content of condensed tannins (20%) [24]. HV contains B-type PACs and the vast majority of the other polyphenols are hydrolysable tannins. The excessive presence of pyrogallol in HV [25] may contribute to the observed initially high, but relatively poorly sustained activity.

Control group was more susceptible to exogenous triggered degradation after 18 months (Figure 2B). This is explained by the activity of endogenous MMP, initiating partial cleavage of unprotected regions in the dentin matrix during long-term storage, thus facilitating degradation by bacterial collagenase. The protective effect of PACs against degradation by bacterial collagenase was sustained for all extracts and at both concentrations. Interestingly, unlike the control group, biodegradation was lower after 18 months aging for all biomodified dentin specimens; except for 6.5% CV, which the protective ability remained the same as for the immediate tests.

When interpreting dentin bioactivity results of highly complex chemical matrices such as PAC-rich extracts, only the major differentiating factors such as the DP, interflavan linkage type, and galloylation can be reasonably correlated with the observed activity. Correlation of additional subtle structural features such as the interflavan linkage position or the stereochemical differences of the constituent monomers or perhaps the 3D conformations is valuable and desirable [17, 26, 27, 28], but requires extensive separation and isolation efforts. However, the present results highlight those factors that are responsible for sustainable dentin biomodification. This new insight helps in further prioritizing the source materials based on the major structural features of the constituent PACs. Considering the large number of biosynthetic permutations and combinations of PACs, pinpointing the role of interflavan linkages and galloylation helps in significantly narrowing down the structural motifs of interest. Moreover, long-term stability test of dentin biomodification by PM fractions was performed in the previous study (27). The PM fractions prepared according to the DP and bioactivities evaluated at five time points (up to 18 months) revealed that the DP did not affect stability. Therefore, it is considered that DP can be excluded as a factor affecting long-term stability.

In summary, this long-term study for the first time demonstrated that plant source-based structural diversity of PACs influences the long-term dentin biomodification effects. While galloylated PAC sources exhibit high initial dentin biomodification, the effects are not as sustainable. In contrast, extract sources with non-galloylated PACs retain the dentin biomechanical and biochemical stabilizing effects in the long-term. The interflavan linkages appears to affect the stability, where A-type linkage favors long-term stabilities.

Highlights.

Biomodification of dentin is a biomimetic approach to enhance the mechanical properties of dentin and resistance to biodegradation of the dentin matrix.

Plant-derived proanthocyanidins are potent dentin biomodification agents containing high structural diversity.

Unique chemical features in proanthocyanidins hold important clues to the sustained interactivity with the dentin matrix components.

This study shows galloylated PAC sources exhibit high initial dentin biomodification, however the effects are not sustainable.

The interflavan monomeric linkages appears to affect the stability, where A-type linkage favors long-term stabilities.

Acknowledgments

Declarations of Interest/Acknowledgment: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [DE21040].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5 References

- [1].Marshall GW Jr, Marshall SJ, Kinney JH, Balooch M. The dentin substrate: structure and properties related to bonding. J Dent 1997; 25:441–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Carrilho MR, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L, Carvalho RM. Mechanical stability of resin-dentin bond components. Dent Mater 2005;21:232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF, Chen SN, McAlpine J, Castellan CS, Phansalkar RS, Aguiar TR, Vidal CM, Napotilano JG, Nam JW, Leme AA. Dentin biomodification: strategies, renewable resources and clinical applications. Dent Mater 2014;30:62–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vidal CM, Zhu W, Manohar S, Aydin B, Keiderling TA, Messersmith PB, Bedran-Russo AK. Collagen-collagen interactions mediated by plant-derived proanthocyanidins: A spectroscopic and atomic force microscopy study. Acta Biomater 2016;41:110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aguiar TR, Vidal CM, Phansalkar RS, Todorova I, Napolitano JG, McAlpine JB, Chen SN, Pauli GF, Bedran-Russo AK. Dentin biomodification potential depends on polyphenol source. J Dent Res 2014;93:417–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vidal CM, Leme AA, Aguiar TR, Phansalkar R, Nam JW, Bisson J, McAlpine JB, Chen SN, Pauli GF, Bedran-Russo A. Mimicking the hierarchical functions of dentin collagen cross-links with plant derived phenols and phenolic acids. Langmuir 2014. 16;30:14887–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khaddam M, Salmon B, Le Denmat D, Tjaderhane L, Menashi S, Chaussain C, Rochefort GY, Boukpessi T. Grape seed extracts inhibit dentin matrix degradation by MMP-3. Front Physiol 2014;5:425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kim GE, Leme-Kraus AA, Phansalkar R, Viana G, Wu C, Chen SN, Pauli GF, Bedran-Russo A. Effect of bioactive primers on bacterial-induced secondary caries at the tooth-resin interface. Oper Dent 2017;42:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Silva Sousa AB, Vidal CM, Leme-Kraus AA, Pires-de-Souza FC, Bedran-Russo AK. Experimental primers containing synthetic and natural compounds reduce enzymatic activity at the dentin-adhesive interface under cyclic loading. Dent Mater 2016;32:1248–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tjäderhane L, Larjava H, Sorsa T, Uitto VJ, Larmas M, Salo T. The activation and function of host matrix metalloproteinases in dentin matrix breakdown in caries lesions. J Dent Res 1998;77:1622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sulkala M, Wahlgren J, Larmas M, Sorsa T, Teronen O, Salo T, Tjäderhane L. The effects of MMP inhibitors on human salivary MMP activity and caries progression in rats. J Dent Res 2001;80:1545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mazzoni A, Tjäderhane L, Checchi V, Di Lenarda R, Salo T, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Breschi L.Role of dentin MMPs in caries progression and bond stability. J Dent Res 2015;94:241–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].La VD, Bergeron C, Gafner S, Grenier D. Grape seed extract suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion by macrophages and inhibits human MMP-1 and −9 activities. J Periodontol 2009;80:1875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bedran-Russo AK, Yoo KJ, Ema KC, Pashley DH. Mechanical properties of tannic-acid-treated dentin matrix. J Dent Res 2009;88:807–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Castellan CS, Pereira PN, Grande RH, Bedran-Russo AK. Mechanical characterization of proanthocyanidin-dentin matrix interaction. Dent Mater 2010;26:968–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Leme-Kraus AA, Aydin B, Vidal CM, Phansalkar RM, Nam JW, McAlpine J, Pauli GF, Chen S, Bedran-Russo AK. Biostability of the proanthocyanidins-dentin complex and adhesion studies. J Dent Res 2017;96:406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Phansalkar RS, Nam JW, Chen SN, McAlpine JB, Napolitano JG, Leme A, Vidal CM, Aguiar T, Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF. A galloylated dimeric proanthocyanidin from grape seed exhibits dentin biomodification potential. Fitoterapia 2015;101:169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lizarraga D, Lozano C, Briedé JJ, van Delft JH, Touriño S, Centelles JJ, Torres JL, Cascante M. The importance of polymerization and galloylation for the antiproliferative properties of procyanidin-rich natural extracts. FEBS J 2007;274:4802–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reddy RR, Phani Kumar BV, Shanmugam G, Madhan B, Mandal AB. Molecular Level Insights on Collagen-Polyphenols Interaction Using Spin-Relaxation and Saturation Transfer Difference NMR. J Phys Chem B 2015;119:14076–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xu Z, Wei H L, Ge Z, Zhu W, Li CM, Comparison of the degradation kinetics of A-type and B-type proanthocyanidins dimers as a function of pH and temperature. Eur Food Res Technol 2015;240:707–717. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sang S, Lee MJ, Hou Z, Ho CT, Yang CS. Stability of tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and formation of dimers and epimers under common experimental conditions. J Agric Food Chem 2005;53:9478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jorgensen EM, Marin AB, Kennedy JA. Analysis of the oxidative degradation of proanthocyanidins under basic conditions. J Agric Food Chem 2004;52:2292–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hewarathna A, Mozziconacci O, Nariya MK, Kleindl PA, Xiong J, Fisher AC, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR, Forrest ML, Volkin DB, Deeds EJ, Schöneich C. Chemical Stability of the Botanical Drug Substance Crofelemer: A Model System for Comparative Characterization of Complex Mixture Drugs. J Pharm Sci 2017;106:3257–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Iglesias J, Pazos M, Lois S, Medina I. Contribution of galloylation and polymerization to the antioxidant activity of polyphenols in fish lipid systems. J Agric Food Chem 2010;58:7423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Touriño S, Lizárraga D, Carreras A, Lorenzo S, Ugartondo V, Mitjans M, Vinardell MP, Juliá L, Cascante M, Torres JL. Highly galloylated tannin fractions from witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) bark: electron transfer capacity, in vitro antioxidant activity, and effects on skin-related cells. Chem Res Toxicol 2008;21:696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nam JW, Phansalkar RS, Lankin DC, Bisson J, McAlpine JB, Leme AA, Vidal CM, Ramirez B, Niemitz M, Bedran-Russo A, Chen SN, Pauli GF. Subtle Chemical Shifts Explain the NMR Fingerprints of Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins with High Dentin Biomodification Potency. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2015;80:7495–7507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nam JW, Phansalkar RS, Lankin DC, McAlpine JB, Leme-Kraus AA, Vidal CM, Gan LS, Bedran-Russo A, Chen SN, Pauli GF. Absolute Configuration of Native Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins with Dentin Biomodification Potency. Journal of Organic Chemistry 2017;82:1316–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Phansalkar RS, Nam JW, Chen SN, McAlpine JB, Leme AA, Aydin B, Bedran-Russo AK, Pauli GF. Centrifugal partition chromatography enables selective enrichment of trimeric and tetrameric proanthocyanidins for biomaterial development. Journal of Chromatography A 2018;1535:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]