Abstract

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most frequent primary immunodeficiency and has a reported prevalence of approximately 1:25,000 to 1:50,000. The fact that it is rarely considered as a diagnosis in adults can lead to diagnostic delay, especially in older patients, and to complications such as bronchiectasis and excess mortality. However, practitioners should first exclude common causes of hypogammaglobulinaemia before considering CVID. Here we present a case of CVID revealed by prolonged fever and complicated with granulomatous manifestations and bronchiectasis in an older woman without a history of recurrent infections.

LEARNING POINTS

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) should be considered in atypical cases with unexplained chronic signs such as fever of unknown origin (even in older patients) after tuberculosis, HIV, neoplasia and connective tissue disease have been ruled out.

Common causes of hypogammaglobulinaemia should be excluded before CVID is considered.

CVID can mimic sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Common variable immunodeficiency, granulomatosis, aged

CASE PRESENTATION

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the most frequent primary immunodeficiency. It is characterized by low levels of immunoglobulins IgG, IgA and sometimes IgM, which result in recurrent and severe infections, associated in some cases with autoimmune manifestations and granulomatous lesions[1,2]. The fact that it is rarely considered as a diagnosis in adults can lead to diagnostic delay, especially in older patients.

The case presented here is interesting because of its late onset. It is important for practitioners to remember that a diagnosis of primary immunodeficiency is still possible in older patients, especially those with atypical clinical features that remain unexplained after routine work-up.

A 63-year-old woman presented with prolonged fever and poor physical condition for several months. Her personal history was unremarkable, but her husband had been treated for pulmonary tuberculosis 7 years previously. She had a family history of systemic lupus in her sister, autoimmune hypothyroidism in her brother and Grave’s disease in her daughter.

Fever and weight loss were associated with liquid diarrhoea and a chronic dry cough. The patient was first admitted to the infections department, where she was investigated for HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and malignancy. Results showed anaemia (haemoglobin 10 g/dl), lymphopenia, inflammatory syndrome (ESR 73 mm, CRP 68 mg/l), a negative tuberculin skin test, negative HIV serology, and negative blood and stool cultures. A CT scan (Fig. 1) showed micronodular and interstitial infiltrates associated with bronchiectasis, which can indicate TB. Three sputum smears were negative for TB. Because of the digestive system involvement, a gastro-intestinal endoscopy was performed and showed nodular gastritis and colitis and isolated giardiasis, which was treated with metronidazole with a good response.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph showing micronodular and interstitial infiltrates in both lungs

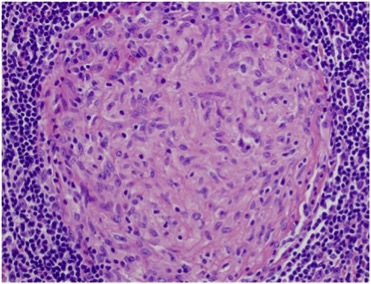

The patient was discharged with a prescription for anti-TB drugs which she took for 9 months without any bacteriological or histological evidence of TB. However, the clinical course was marked by the occurrence of diffuse arthritis and lymphadenopathy and previous clinical and radiological signs persisted. Consequently, as systemic disease was suspected, the patient was admitted to the internal medicine department for investigation. Immunological parameters (antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, ACPA, ANCA, Coombs) and kidney investigations were negative. A lymph node biopsy showed the presence of non-necrotizing granuloma (Fig. 2). New ocular symptoms were diagnosed as granulomatous uveitis.

Figure 2.

Node biopsy showing non-necrotizing granuloma

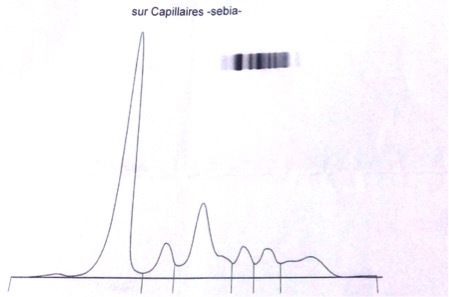

There was a strong suspicion of sarcoidosis because of the pulmonary involvement, the ocular and joint manifestations, the presence of granulomatous disease in the biopsy and the non-response to anti-TB drugs. The work-up showed normal angiotensin converting enzyme and calcium and phosphorus levels. Lymphoma was also a possible diagnosis but an immunohistochemistry study performed on the lymph node biopsy was negative as was a bone marrow biopsy. Protein electrophoresis showed hypogammaglobulinaemia (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Protein electrophoresis showing hypogammaglobulinaemia

Further investigations revealed decreased serum immunoglobulin levels: IgG 1.1, IgA 0.3 and IgM 0.4. A flow cytometric study of lymphocyte subpopulations showed a low CD19 count (2%) with a normal range of T lymphocytes. These findings suggested a primary immunodeficiency, in particular CVID.

In light of these results, a CVID with granulomatous manifestations was diagnosed based on European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) criteria (Table 1). Our patient was treated with immunoglobulin perfusions, oral corticosteroids (especially for the ocular involvement), respiratory physiotherapy and azithromycin for bronchiectasis. Evolution was good: the fever resolved, respiratory symptoms have improved, and our patient has gained weight and recovered her vision.

Table 1.

European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) 2014 criteria for common variable immunodeficiency (CVID)[3]

At least one of the following:

|

AND

|

| AND Either:

|

AND

|

| AND No evidence of T cell deficiency defined as two of the following:

|

DISCUSSION

Few cases of primary immunodeficiency are reported in patients over 40 years of age[1]. Practitioners rarely consider primary immunodeficiency, especially in older patients or in the absence of recurrent infections, as in our case, which can cause diagnostic delay resulting in complications such as bronchiectasis and excess mortality.

Granulomatous manifestations are seen in 8–22% of CVID patients[2], which should encourage practitioners to consider it. These patients present with a clinical picture that mimics sarcoidosis, hence the description ‘sarcoidosis-like’ with unusual hypogammaglobulinaemia[2]. Several signs mentioned in this case report can also be seen in sarcoidosis, granulomatous uveitis, lymphadenopathy and disease with respiratory involvement and histological evidence of granuloma. Before retaining CVID as a diagnosis, practitioners should first exclude common causes of hypogammaglobulinaemia such as nephrotic syndrome, protein loss enteropathy, lymphoma and drugs (chemotherapy, corticosteroids, etc.).

We did not explore this primary immunodeficiency further because of financial constraints. However, CVID can be characterized with B cell immunophenotyping, where the granulomatous profile shows a severe reduction in switched memory B cells and a high level of CD21 low B cells[2, 3].

We did not perform genetic analysis in our patient either because of technical problems. The genetic origin of CVID is still obscure, but it has been well established that CVID is a highly heterogeneous and polygenic disease; several studies have described inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS), tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 13B (TNFRSF13B, also known as TACI), tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 13C (TNFRSF13C, also known as BAFFR) and D19 genetic polymorphisms[3].

Our patient was successfully treated with monthly immunoglobulin perfusions. Immunoglobulin perfusions have shown efficacy in decreasing infectious events and in exerting anti-inflammatory effects[3, 4]. The presence of granulomatous manifestations requires specific treatment because they evolve independently and do not respond to immunoglobulin replacement alone[3]. Corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of treatment for granulomatous manifestations but sometimes are insufficient to obtain remission. However, other immunosuppressive therapies can be used such as rituximab or azathioprine, but do present an increased risk of infectious complications[2]. Bronchiectasis was the second main problem in our patient and is generally managed with respiratory physiotherapy. Bronchiectasis is correlated with a poor prognosis and has an independent clinical course which responds poorly to immunoglobulin perfusions[3]. The use of azithromycin for its anti-inflammatory effect has improved the quality of life in such patients[5].

A clinical picture of sarcoidosis associated with hypogammaglobulinaemia should suggest a diagnosis of CVID at any age, even in the absence of a typical history of recurrent infections. However, one should be very careful to exclude common causes of immunoglobulin loss before considering CVID.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gathmann B, Mahlaoui N, Gerard L, et al. Clinical picture and treatment of 2212 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boursiquot J-N, Gérard L, Malphettes M, et al. Granulomatous disease in CVID: retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and treatment efficacy in a cohort of 59 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:84–95. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott JK, Gelfend EW. Common variable immunodeficiency: diagnosis, management, and treatment. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35:637–658. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prezzo A, Cavaliere FM, Bilotta C, Iacobini M, Quinti I. Intravenous immunoglobulin replacement treatment does not alter polymorphonuclear leukocytes function and surface receptors expression in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Cell Immunol. 2016;306–307:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandit C, Hsu P, van Asperen P, Mehr S. Respiratory manifestations and management in children with common variable immunodeficiency. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016;19:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]