Abstract

Background/Aims

To investigate the treatment efficacy and renal safety of long-term tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) therapy in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with preserved renal function.

Methods

The medical records of 919 CHB patients who were treated with TDF therapy were reviewed. All patients had preserved renal function with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Results

A total of 426 patients (184 treatment-naïve and 242 treatment-experienced) were included for analysis. A virologic response (VR) was defined as achieving an undetectable serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level, and the overall VR was 74.9%, 86.7%, and 89.4% at the 1, 2, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. Achieving a VR was not influenced by previous treatment experience, TDF combination therapy, or antiviral resistance. In a multivariate analysis, being hepatitis B e antigen positive at baseline and having a serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months were associated with lower VR rates during the long-term TDF therapy. The overall renal impairment was 2.9%, 1.8%, and 1.7% at the 1, 2, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. With regard to renal safety, underlying diabetes mellitus (DM) and an initial eGFR of 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 were significant independent predictors of renal impairment.

Conclusions

TDF therapy appears to be an effective treatment option for CHB patients with a preserved GFR. However, patients with underlying DM and initial mild renal dysfunction (eGFR, 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2) have an increased risk of renal impairment.

Keywords: Antiviral agents, Hepatitis B, chronic, Tenofovir, Treatment outcome, Renal insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global health problem since it is a major cause of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Despite recent advancements in antiviral therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NA), it is still difficult to completely eliminate the covalently closed circular DNA of HBV. Therefore, the primary goal of the current NA therapy in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients is long-term suppression of HBV replication.1 However, long-term NA therapy is associated with concerns of drug resistance and toxicity.2,3 Initially, the wide use of less potent NAs, which have a low genetic barrier to resistance, was associated with high risk of drug resistance.4 Treatment with entecavir (ETV), despite its high genetic barrier, also reported increased risk of resistance.5,6 Furthermore, although oral NAs are generally well-tolerated by patients and safe to use, its long-term use can cause various adverse effects.7,8

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a nucleotide analogue, was shown to be highly effective in achieving undetectable levels of serum HBV DNA and normal range of alanine amino-transferase (ALT) levels.9,10 Sustained viral suppression with TDF treatment over a 5-year period was associated with histological improvement in 87% of patients and 51% fibrosis regression.11 Treatment with TDF in CHB patients is well tolerated without any significant adverse events and showed high rates of viral suppression without the development of drug resistance in clinical trials.12,13 Furthermore, TDF monotherapy or TDF-based combination therapy was highly effective in achieving long-term viral suppression among patients with previous NA treatment failure.14–18 Meanwhile, renal safety is one of the greatest concerns with respect to the long-term administration of TDF in CHB patients, and it is still debatable in clinical real-life data.19–23 Recently, EASL guideline recommended that one of the risk factors of renal safety is an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. However, the renal safety of long-term TDF therapy among patients with preserved GFR (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2) is unclear.

In Korea, TDF is widely used for naïve CHB patients as well as for those with previous NA experience since it was approved for HBV treatment in 2012. Interestingly, in Korea, a large number of CHB patients with previous treatment experience has a history of long-term lamivudine/adefovir (LAM-ADV) treatment owing to the domestic insurance policy. Moreover, before approval of TDF therapy, substantial patients treated with ADV resistance were rescued with ETV, but treatment efficacy of ETV was not sufficient. Although Korea is a unique area because treatment-experienced patients are prevalent as compared with other countries, there has been no published real-world data on this issue in Korea until now. In this study, we aimed to investigate the treatment efficacy and safety of long-term TDF therapy for a 3-year period in CHB patients with preserved GFR. We also analyzed the factors associated with virologic response and renal safety during long-term TDF therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study patients

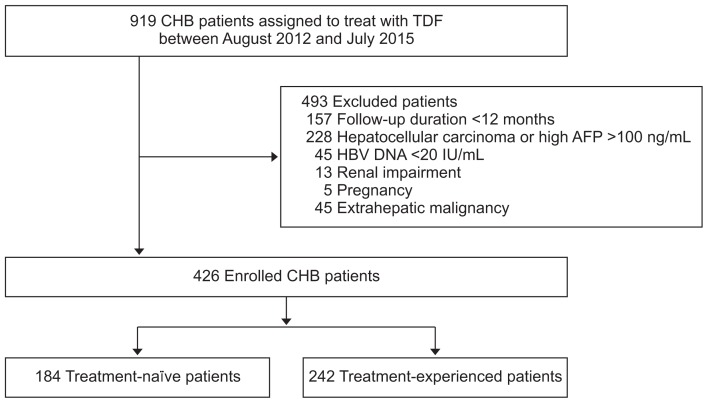

In this cohort study, we reviewed the medical records of 919 CHB patients who were treated with TDF 300 mg daily between August 2012 to December 2016 at Chonbuk National University Hospital (Jeonju, Republic of Korea). The inclusion criteria were: age >18 years, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity without hepatitis C virus (HCV), HCV, or human immunodeficiency virus co-infection, for more than 6 months, and a minimum follow-up duration of 12 months. We included both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients receiving either TDF monotherapy or TDF combination therapy, that is, TDF in combination with a second NA. Patients with the following conditions at the time of initiation of TDF therapy were excluded: undetectable serum HBV DNA (<20 IU/mL), serum phosphate level <2.0 mg/dL, renal impairment, that is, eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, pregnancy, HCC or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level >100 ng/mL, and other malignancy. Finally, the remaining 426 patients (184 treatment-naïve and 242 treatment-experienced) were enrolled for analysis in this study (Fig. 1). This study was conducted in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chonbuk National University Hospital (IRB No. 2015-10-020-002). The written informed consents were obtained.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment in this study.

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

2. Laboratory assays and routine follow up examinations

Serum HBV DNA was quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction assay using the COBAS Taq-Man HBV quantitative test (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Branchburg, NJ, USA), which had a lower limit of quantification (20 IU/mL). HBV DNA levels were logarithmically transformed for analysis. The presence of HBV DNA polymerase gene mutations conferring resistance to LAM (rtM204V/I/S, rtL180M), ADV (rtA181T/V, rtN236T), and ETV (rtL180M+rtM204V/I±rtI169T±rtV173L±rtM250V/I/L/M±rtT184S/A/I/L/G/C/M±rtS202I/G) was assessed via Restriction Fragment Mass Polymorphism (RFMP) assay. Serum ALT was measured with an enzymatic assay. Serum HBsAg, antibodies to HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and antibodies to HBeAg (anti-HBe) were detected by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Routine biochemical tests, including serum ALT, creatinine, and phosphorus were performed using a sequential multiple auto-analyzer. During the treatment period, patients were routinely followed up every 1 to 3 months. Serum HBV DNA, ALT, creatinine, eGFR, and phosphorus were assessed routinely every 3 months. HBeAg/anti-HBe and serum AFP level were routinely tested every 6 months. Measurement of eGFR was assessed using the CKD-EPI creatinine Equation.24 Ultrasonography or abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed for HCC surveillance every 6 months.

3. Definitions

Virologic response was defined as achieving undetectable serum HBV DNA level (<20 IU/mL) during the treatment period. Virologic breakthrough was defined as an increase in the serum HBV DNA level of more than 1 log10IU/mL from nadir during treatment. HBeAg seroconversion was defined for HBeAg-positive patients as HBeAg loss and seroconversion to anti-HBe during treatment. Normalization of ALT was defined as <40 IU/L. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as a resistance to two or more groups of antiviral drugs; that is, L-nucleoside (LAM, LdT, clevudine), cyclopentane (ETV), or nucleotide analogue (ADV and TDF). Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by the identification of liver surface nodularity with splenomegaly based on the imaging studies or if clinical findings were suggestive of cirrhotic conditions, such as splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, varices, and ascites. HCC was diagnosed based on the guidelines proposed by the Korean Liver Cancer Study Group-National Cancer Center.25 Renal impairment was defined as elevation of serum creatinine 0.3 mg/dL above the baseline level or a decrease of eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Hypophosphatemia was defined as serum phosphorus of less than 2.0 mg/dL.

4. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or numbers (percentage). We compared continuous or categorical variables between the groups using t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher exact test. Factors associated with virologic response and renal impairment were analyzed by Cox proportional hazard analysis. Cumulative rates of virologic response were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier method and compared using log-rank tests. The results were analyzed using statistical software package SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All tests of significance were two-tailed; p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics of study patients

The baseline characteristics of 426 CHB patients with comparison between treatment-naïve versus treatment-experienced patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of all participants was 48.4 years; 283 (66.4%) were male, 134 (31.5%) had liver cirrhosis, 287 (68.0%) were HBeAg positive. The mean serum HBV DNA level was 4.8 log10IU/mL. The median duration of TDF based therapy was 28.4 months (range, 12 to 36 months). The cohort included 184 treatment-naïve patients and 242 treatment-experienced patients. Patients in both groups were similar in body mass index, alcohol intake, and frequency of diabetes mellitus (DM). However, treatment-experienced patients were generally older, higher frequency of males, lower rate of cirrhosis, and had significantly lower serum ALT and HBV DNA levels compared with the treatment-naïve patients (Table 1). HBeAg positive patients were more common in the treatment-experienced group. For those in the treatment-naïve group, all were treated with TDF monotherapy; whereas those in the treatment-experienced group, 167 (69.0%) were treated with TDF monotherapy, and the remaining 75 patients (31.0%) were treated with TDF combined with another NA therapy. In the treatment-experienced group, the types of previous genotypic resistance included LAM- resistance (R) in 143 (91.7%), ADV-R in 25 (16.0%), ETV-R in 30 (19.2%), and MDR in 43 (17.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Subjects

| Characteristics | Total (n=426) | Treatment-naïve (n=184) | Treatment-experienced (n=242) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 48.4±11.8 | 46.9±12.4 | 49.5±11.2 | 0.03 |

| Male sex | 283 (66.4) | 112 (60.9) | 171 (70.7) | 0.04 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.6±3.1 | 23.6±3.4 | 23.6±2.8 | 0.99 |

| Alcohol intake | 139 (32.7) | 69 (37.5) | 70 (29.0) | 0.07 |

| DM | 23 (5.4) | 14 (7.6) | 9 (3.7) | 0.13 |

| Cirrhosis | 134 (31.5) | 73 (39.7) | 61 (25.2) | 0.002 |

| ALT, IU/L | 110.3±323.4 | 188.1±470.1 | 51.1±92.0 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.06 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 103.4±14.1 | 105.0±15.3 | 102.2±13.0 | 0.05 |

| HBeAg-positive | 287 (68.0) | 105 (57.1) | 182 (76.5) | <0.001 |

| HBV DNA, log10IU/mL | 4.8±2.2 | 6.2±1.7 | 3.8±1.8 | <0.001 |

| HBV DNA ≥8 logIU/mL | 51 (12.0) | 43 (23.4) | 8 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| TDF therapy | <0.001 | |||

| TDF monotherapy | 351 (82.4) | 184 (100.0) | 167 (69.0) | |

| TDF combination therapy* | 75 (17.6) | 0 | 75 (31.0) | |

| Previous NA resistant mutations† | - | - | - | |

| LAM-R | 143 (91.7) | |||

| ADV-R | 25 (16.0) | |||

| ETV-R | 30 (19.2) | |||

| MDR | 43 (17.8) | |||

| Follow-up duration, mo | 28.4 (12–36) | 25.8 (12–36) | 30.4 (12–36) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean±SD, number (%), or median (range).

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; NAs, nucleos(t)ide analogues; LAM-R, lamivudine resistance; ADV-R, adefovir-resistance; ETV-R, entecavir-resistance; MDR, multidrug resistance.

TDF combined with other NAs;

LAM-R mutations include rtM204V/I±rtL180M, ADV-R mutations include rtA181T/V and rtN236T/V, and ETV-R mutations include rtT184, rtI169, and rtS202.

2. Treatment outcomes of long-term TDF therapy

The treatment outcomes of TDF therapy are summarized in Table 2. The overall virologic responses were 74.9%, 86.7%, and 89.4% at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. It was not significantly different between treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients. The overall rates of HBeAg seroconversion/loss were 9.5%, 13.7%, 13.9% at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. It was higher in the treatment-naïve group than in the treatment-experienced group at 1-year (17.2% vs 5.2%, p=0.002) and 2-year follow-up (27.0% vs 7.2%, p<0.001). The overall rates of serum ALT normalization were 81.4%, 84.8%, and 85.2% at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. It was higher in the treatment-naïve group compared with the treatment-experienced group at 2-year follow-up (91.0% vs 81.0%, p=0.018). However, it was not significantly different at 1-year and 3-year follow-ups. HB-sAg seroconversion occurred in one patient at 1-year and one patient at 2-year follow-ups, respectively. Viral breakthrough occurred in three patients (0.7%) at the 1-year mark, in four patients (1.2%) at the 2-year mark, and in three patients (1.3%) at the 3-year mark. All of them showed poor medication compliance and viral breakthrough resolved after retreatment of TDF. None of them exhibited any resistant or novel mutation to TDF. The overall rates of HCC development were 1.2%, 1.5%, 1.7% at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively.

Table 2.

Treatment Outcomes of Long-Term TDF Therapy in the Treatment-Naïve and Treatment-Experienced CHB Groups

| Characteristics | 1 Year (n=426) | 2 Years (n=347) | 3 Years (n=236) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virologic response | Total | 319/426 (74.9) | 301/347 (86.7) | 211/236 (89.4) |

| Naïve | 133/184 (72.3) | 119/134 (88.8) | 66/78 (84.6) | |

| Experienced | 186/242 (76.9) | 182/213 (85.4) | 145/158 (91.8) | |

| p-value | 0.334 | 0.462 | 0.145 | |

| HBeAg seroconversion/loss | Total | 26/273 (9.5) | 31/227 (13.7) | 22/151 (13.9) |

| Naïve | 17/99 (17.2) | 20/74 (27.0) | 9/40 (22.5) | |

| Experienced | 9/174 (5.2) | 11/153 (7.2) | 13/109 (11.9) | |

| p-value | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.176 | |

| ALT normalization | Total | 345/424 (81.4) | 291/343 (84.8) | 196/230 (85.2) |

| Naïve | 152/182 (83.5) | 121/133 (91.0) | 64/77 (83.1) | |

| Experienced | 193/242 (79.8) | 170/210 (81.0) | 132/153 (86.3) | |

| p-value | 0.324 | 0.018 | 0.660 | |

| Virologic breakthrough | Total | 3/426 (0.7) | 4/347 (1.2) | 3/236 (1.3) |

| Naïve | 0/184 (0.0) | 1/134 (0.7) | 3/78 (3.8) | |

| Experienced | 3/242 (1.2) | 3/213 (1.4) | 0/158 (0.0) | |

| p-value | 0.352 | 0.963 | 0.062 | |

| Genotypic resistance | Total | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Naïve | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Experienced | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p-value | - | - | - | |

Data are presented as number/number (%).

TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

3. Factors associated with virologic response

In the univariate analysis, age >60 years, male sex, body mass index, alcohol intake, presence of DM or cirrhosis, previous treatment experience, ADV-R, MDR, TDF combination therapy, platelet count, and serum ALT level did not influence the achievement of virologic response. Conversely, HBeAg positivity, serum HBV DNA level at baseline, serum HBV DNA level ≥8 log10IU/mL at baseline, and serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months were significantly associated with virologic response during long-term TDF therapy (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, HBeAg-positive (hazard ratio [HR], 0.727; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.91; p=0.006) and serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months (HR, 0.271; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.58; p=0.001) were significant independent factors associated with lower rate of virologic response (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Virologic Response

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age >60 yr | 0.706 | 0.949 | 0.723–1.246 | |||

| Male sex | 0.620 | 0.948 | 0.768–1.171 | |||

| BMI | 0.751 | 1.007 | 0.963–1.054 | |||

| Alcohol intake | 0.099 | 0.831 | 0.667–1.035 | |||

| DM | 0.878 | 0.965 | 0.615–1.514 | |||

| Cirrhosis | 0.242 | 1.138 | 0.917–1.412 | |||

| Treatment-experienced vs naïve | 0.493 | 1.074 | 0.876–1.317 | |||

| ADV resistance | 0.809 | 0.948 | 0.617–1.459 | |||

| Multi-drug resistance | 0.596 | 0.913 | 0.653–1.277 | |||

| TDF combination therapy vs TDF monotherapy | 0.358 | 0.881 | 0.673–1.154 | |||

| Platelets, ×106/mm3 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 0.999–1.001 | |||

| ALT, IU/L | 0.767 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | |||

| HBeAg positive vs negative | 0.001 | 0.684 | 0.549–0.851 | 0.006 | 0.727 | 0.580–0.912 |

| HBV DNA, IU/mL, baseline | 0.003 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.367 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 |

| HBV DNA ≥8 log10U/mL at baseline vs <8 log10U/mL | 0.007 | 0.622 | 0.440–0.880 | 0.760 | 1.197 | 0.377–3.797 |

| HBV DNA ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 mo vs <2,000 IU/mL | <0.001 | 0.256 | 0.121–0.545 | 0.001 | 0.271 | 0.127–0.579 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; ADV, adefovir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

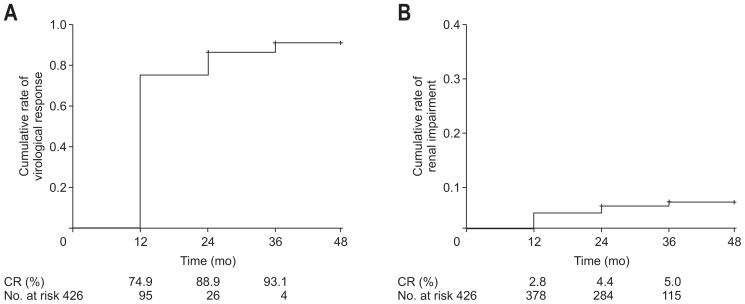

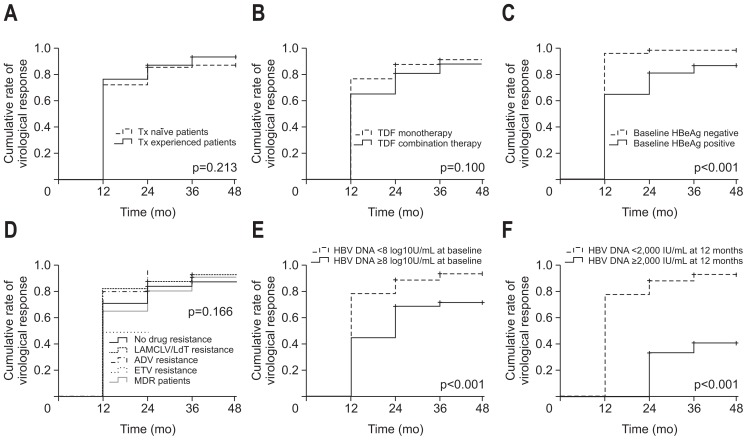

The overall cumulative rates of virologic response are shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative rates of virologic response in accordance with the subgroups are shown in Fig. 3. The cumulative rates of virologic response was not significantly different between the subgroups, such as treatment-naïve versus treatment experienced, TDF monotherapy versus TDF combination therapy, no resistance versus LAM/CLV/LdT-R versus ADV-R versus ETV-R versus MDR patients (Fig. 3A, B, D). However, those who were HBeAg-positive at baseline, HBV DNA ≥8 log10U/mL at baseline, and serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months showed significantly lower rates of virologic response during long-term TDF therapy (Fig. 3C, E, F).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative rates (CR) of virologic response (A) and renal impairment (B) among all chronic hepatitis B patients.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative rates (CR) of virologic response (serum HBV DNA level <20 IU/mL) in the subgroup analysis. (A) Treatment-naïve vs treatment-experienced patients. (B) TDF-monotherapy vs TDF-combination therapy patients. (C) HBeAg-negative vs HBeAg-positive patients. (D) No resistance vs LAM/CLV/LdT-resistance vs ADV-resistance vs ETV-resistance vs MDR. (E) HBV DNA <8 log10 U/mL at baseline vs HBV DNA ≥8 log10 U/mL at baseline. (F) HBV DNA <2,000 IU/mL at 12 months vs HBV DNA ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months.

Tx, treatment; HBV, hepatitis B virus; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; LAM, lamivudine; CLV, clevudine; LdT, telbivudine; ADV, adefovir; ETV, entecavir; MDR, multidrug resistance.

4. Renal safety during long-term TDF therapy

Renal safety profiles during the long-term TDF therapy are summarized in Table 4. The mean serum creatinine level and eGFR were not significantly altered during the follow-up period. Among the total study population, the incidence of renal impairment was seen in 12 out of 411 (2.9%) at 1-year, six out of 342 (1.8%) at 2-year, and four out of 229 (1.7%) at 3-year follow-up time points. It was not significantly different between the treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced group (3.4% vs 2.6% at 1-year, 1.5% vs 1.9% at 2-year, and 1.3% vs 2.0% at 3-year follow-ups, respectively). There were two patients at 1-year and one patient at 3-year of follow-up who modified their TDF dose due to reduced GFR and all of them were resolved without treatment interruption. Although four patients recovered their renal functions during follow-up periods, the others maintained gradually decreased renal function. In addition, patients with renal impairment showed rapid decline of GFR as −34.2±11.7, −28.2±12.5, and −38.4±7.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. During the 3 years of follow-up, two patients were expired. One patient who had been maintained TDF monotherapy advanced to the hepatorenal syndrome. The other patient was not a renal impairment-related death which was variceal bleeding case underlying HCC. The incidence of hypophosphatemia (<2.0 mg/dL) was 0 out of 359 (0.0%) at 1-year, three out of 294 (1.0%) at 2-year, and one out of 191 (0.5%) at 3-year follow-ups.

Table 4.

Renal Safety during Long-Term Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Therapy

| Characteristics | 1 Year (n=426) | 2 Years (n=347) | 3 Years (n=236) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean serum creatinine level changes, mg/dL | Total | 0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 |

| Naïve | 0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 | |

| Experienced | 0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 | −0.0±0.1 | |

| p-value | 0.739 | 0.380 | 0.511 | |

| Mean eGFR changes, mL/min/1.73 m2 | Total | −1.7±11.1 | −0.4±10.0 | −1.5±10.3 |

| Naïve | −1.4±11.6 | −0.9±11.0 | −0.7±10.5 | |

| Experienced | −2.0±10.7 | −0.1±9.3 | −1.9±10.2 | |

| p-value | 0.621 | 0.508 | 0.401 | |

| Renal impairment | Total | 12/411 (2.9) | 6/342 (1.8) | 4/229 (1.7) |

| Naïve | 6/179 (3.4) | 2/132 (1.5) | 1/76 (1.3) | |

| Experienced | 6/232 (2.6) | 4/210 (1.9) | 3/153 (2.0) | |

| p-value | 0.872 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Mean serum phosphorus level changes, mg/dL | Total | −0.0±0.6 | −0.0±0.6 | −0.1±0.5 |

| Naïve | −0.0±0.6 | −0.0±0.6 | −0.1±0.6 | |

| Experienced | −0.0±0.5 | −0.1±0.5 | −0.0±0.5 | |

| p-value | 0.633 | 0.729 | 0.492 | |

| Hypophosphatemia | Total | 0/359 (0.0) | 3/294 (1.0) | 1/191 (0.5) |

| Naïve | 0/169 (0.0) | 0/125 (0.0) | 1/72 (1.4) | |

| Experienced | 0/190 (0.0) | 3/169 (1.8) | 0/119 (0.0) | |

| p-value | - | 0.363 | 0.799 | |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number/number (%).

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

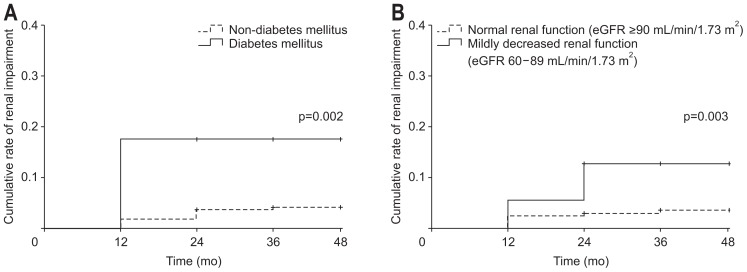

5. Factors associated with renal impairment

In the univariate analysis, age >60 years, DM, and eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 were significantly associated with renal impairment during long-term TDF therapy (Table 5). Multivariate analysis showed underlying DM (HR, 4.803; 95% CI, 1.55 to 14.87; p=0.007) and eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR, 3.119; 95% CI, 1.179 to 8.32; p=0.023) as independent significant factors associated with renal impairment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors Associated with Renal Impairment

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Age >60 yr | 0.032 | 2.728 | 1.089–6.838 | 0.322 | 1.649 | 0.612–4.444 |

| Male sex | 0.715 | 1.195 | 0.459–3.110 | |||

| BMI | 0.748 | 1.027 | 0.874–1.207 | |||

| Alcohol intake | 0.068 | 3.139 | 0.920–10.714 | |||

| DM | 0.006 | 4.712 | 1.574–14.106 | 0.006 | 4.790 | 1.552–14.784 |

| Cirrhosis | 0.184 | 1.817 | 0.753–4.387 | |||

| Treatment-experienced vs naïve | 0.834 | 0.910 | 0.377–2.197 | |||

| ADV experienced | 0.858 | 0.905 | 0.302–2.707 | |||

| TDF combination therapy vs TDF monotherapy | 0.166 | 0.241 | 0.032–1.803 | |||

| Platelets, ×106/mm3 | 0.090 | 0.994 | 0.987–1.001 | |||

| ALT, IU/L | 0.686 | 0.999 | 0.997–1.002 | |||

| Initial eGFR 60–89, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.005 | 3.680 | 1.468–9.224 | 0.014 | 3.413 | 1.276–9.131 |

| HBV DNA at baseline, IU/mL | 0.224 | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | |||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; ADV, adefovir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

The overall cumulative rates of renal impairment are shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative rates of renal impairment in accordance with the subgroups are shown in Fig. 4. Patients who had underlying DM and represented initial mildly decreased renal function (eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2) showed significantly higher rates of renal impairment during long-term TDF therapy.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative rate of renal impairment in the subgroup analysis. (A) Patients with vs without diabetes mellitus. (B) Patients with normal renal function (eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2) vs patients with mildly decreased renal function (eGFR 60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2).

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

DISCUSSION

Antiviral therapy for CHB is the most widely used strategy for improving survival by preventing progression to cirrhosis and HCC. Because HBsAg seroconversion rate is very low, long-term use of antiviral agents is necessary for sustained viral suppression. Although TDF showed a high antiviral efficacy in a long-term registration trial, treatment strategy and efficacy may be influenced by various factors of individual in the real world.26,27 Therefore, real-life data reflecting the heterogeneity of patients treated with antiviral therapy depending on the various conditions, and factors associated with virological response and adverse events, are needed to be elucidated.

In this study, TDF based therapy was highly effective for CHB patients for up to 3 years. In the multivariate analysis, HBeAg-positive and serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months were independent factors associated with lower virologic response. However, the treatment outcomes were not significantly affected by treatment experience, TDF combination therapy, and previous antiviral resistance. This study included CHB patients with preserved renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2) at baseline and the incidence of renal impairment was quite low. The presence of DM and eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 were independent factors associated with renal impairment.

Prior antiviral treatment experience is one of the important factors affecting drug efficacy because experienced individuals may likely have developed drug resistance, genetic mutation, or virologic non-response. Before the emergence of TDF, many kinds of antiviral drugs, including ETV, have relatively high frequency of drug resistance, although they may be used in combination. Some previous studies demonstrated that previous ADV-experienced patients have inferior efficacy of TDF compared with NA-naïve patients.28 Some reported TDF mono-therapy showed superior efficacy compared with LMV plus ADV or ETV plus ADV in LAM-R CHB patients.29,30 As a combination strategy, regarding previous reports, the efficacy of TDF mono- and combination treatments was similar,31 and TDF-ETV combination therapy revealed a high rate of achieving virologic suppression regardless of prior treatment experience without resistance.32

Regarding our data, both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced groups showed a high frequency of virologic response, ALT normalization, and low virologic breakthrough without statistically significant difference in comparison of these two groups. The difference among them was observed with respect to HBeAg loss/seroconversion at 1-year and 2-year follow-up time points. Prior exposure to antiviral therapy, as well as the development of resistance may influence the results. When we review the data, there were only one patient in the treatment-experienced group who showed HBeAg seroconver-sion among the 31 patients with multi-drug resistance. In the current study, viral breakthrough occurred in 10 patients during the follow-up duration. We review the data of individuals and found that all of them showed non-compliance with antiviral drugs and viral breakthrough resolved after retreatment of TDF. Similarly, in other studies, viral breakthroughs occurred infrequently and were associated with non-compliance with antiviral drugs.33–35 In our study, none of them exhibited any resistance or novel mutation to TDF.

In Korea, LMV-ADV therapy was a treatment option for patients with LMV-R. Given the similarity between TDF and ADV, there was a concern about the resistance and inferior treatment response of TDF in ADV-experienced CHB patients, especially who had ADV-R mutations.16 In the present study, when we reviewed the virologic response only in ADV-experienced patients (n=91), virologic response was 80.2%, 89.3%, and 93.8% at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year follow-ups, respectively. The result was similar or slightly higher compared with the overall treatment experienced patients. Our data suggest that the use of TDF is highly effective regardless of previous ADV exposure.

Sustained virologic response is one of the most important parameters that reflect the treatment response and is crucial to the prevention of the progression of CHB to cirrhosis, HCC, and liver complication-related deaths. As aforementioned, prior antiviral treatment experience, drug combination therapy, and drug resistance may influence the virologic response. However, cumulative virologic response was not affected with respect to such factors in comparison in this study. Our data suggests that baseline HBeAg positive and HBV DNA levels at 12 months can predict the efficacy of long-term TDF treatment. In previous clinical trials of long-term TDF therapy, participants were separated with regard to HBeAg positivity and, although long-term cumulative virologic response was similar between the two groups, the virologic response rate in early stages was relatively lower in HBeAg-positive patients.27 In one previous study, more than 70% of the study cohort with antiviral resistance showed HBeAg positivity.36 Regarding the relationship between HBV DNA level and virologic response, several previous studies reported that the baseline serum HBV DNA level in CHB patients who were resistant to antiviral therapy significantly influenced the achievement of virologic response when receiving TDF mo-no-rescue therapy.36 Lo et al.37 reported that patients with HBV DNA <20,000 IU/mL had higher virologic response than those with HBV DNA ≥ 20,000 IU/mL.

Renal safety is one of the greatest concerns with respect to the long-term administration of TDF in CHB patients. Because TDF is eliminated through urine by the kidneys, decreased renal function may interfere with the treatment response, resulting in a worsening of renal function.38 There are some reports of Fanconi syndrome mainly in the case of long-term use. AASLD suggests no particular preference between ETV and TDF regarding the potential long-term risks of renal and bone complications.39 According to the 2017 EASL guidelines, one of the risk factors of renal safety is eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Careful use of TDF should be considered when patients possess other risk factors of renal dysfunction. The EASL guidelines also recommend the use of tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) as a switching therapy.4 Dose of TDF should be adjusted in accordance with renal function and the dose adjustments are required in case of eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2. When initiating TDF, risk assessment for renal dysfunction is recommended with close monitoring of renal function annually.

In the present study, TDF monotherapy or TDF-based combination therapy was shown to be relatively well tolerated. No serious adverse events were noted, and no discontinuation of the drug occurred due to nephrotoxicity. Some previous studies reported that older age, pre-existing renal insufficiency, prior long-term use of ADV, hypertension, and DM are associated with renal dysfunction.40–42 Although such parameters were not statistically significant for predicting renal impairment in this study, we suggest the importance of close monitoring of GFR and tubular function, especially in patients with mildly decreased GFR (eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2) as well as DM patients. On the other hand, TAF could represent a new therapeutic option for patients with high risk of renal dysfunction, including those with DM and initial eGFR of less than 90 mL/min/1.73 m2.43,44

There are several limitations to consider. First, this study was single-center cohort study and several factors relevant to the baseline characteristics were different between the treatment-naïve and treatment experienced groups due to the retrospective nature of this study. Second, the follow-up duration of individuals was affected by the time of TDF initiation. Except those with follow-up loss, many of the enrolled patients who initiated the drug in the late period have censored data due to expiration of the observation period. Moreover, the distribution of time period patients enrolled may differ between the two groups regarding reimbursement policy. Third, our data did not consider the urinalysis results of patients, such as proteinuria or albuminuria, as an indicator of renal function. Underlying hypertension and osteopenia with bone mineral density before and after treatment were also not assessed. Finally, our strict inclusion criteria may have influenced the results. Although this study has these limitations, our data is promising because it is obtained from a real-life experience and supports the previous results of clinical trials.

In conclusion, TDF therapy for CHB patients is a strongly effective treatment option for achieving virologic response regardless of previous treatment experience, TDF combination therapy, and antiviral resistance. HBeAg-positive at baseline and serum HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/mL at 12 months were independent factors associated with virologic response. The incidence of renal impairment during long-term TDF therapy was relatively low among CHB patients with preserved GFR at baseline. However, the presence of DM and initial mildly decreased GFR (eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2) may increase the risk of renal toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Fund of Biomedical Research Institute, Chonbuk National University Hospital.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. KASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22:18–75. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.22.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dienstag JL. Benefits and risks of nucleoside analog therapy for hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S112–S121. doi: 10.1002/hep.22920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghany MG, Doo EC. Antiviral resistance and hepatitis B therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S174–S184. doi: 10.1002/hep.22900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Two-year assessment of entecavir resistance in Lamivudine-refractory hepatitis B virus patients reveals different clinical outcomes depending on the resistance substitutions present. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:902–911. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00833-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–1514. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayaaslan B, Guner R. Adverse effects of oral antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis B. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:227–241. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoulim F, Locarnini S. Management of treatment failure in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2012;56(Suppl 1):S112–S122. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:107–119. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09354562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo G, Tomlinson G, Nishikawa Y, et al. Tenofovir and entecavir are the most effective antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1218–1229. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corsa AC, Liu Y, Flaherty JF, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate through 96 weeks of treatment in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:2106–2112.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buti M, Tsai N, Petersen J, et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety of treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1457–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3486-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg T, Zoulim F, Moeller B, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of emtricitabine plus tenofovir DF vs. tenofovir DF monotherapy in adefovir-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2014;60:715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg T, Marcellin P, Zoulim F, et al. Tenofovir is effective alone or with emtricitabine in adefovir-treated patients with chronic-hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1207–1217. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim YS, Yoo BC, Byun KS, et al. Tenofovir monotherapy versus tenofovir and entecavir combination therapy in adefovir-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients with multiple drug failure: results of a randomised trial. Gut. 2016;65:1042–1051. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fung S, Kwan P, Fabri M, et al. Randomized comparison of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:980–988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho HJ, Kim SS, Shin SJ, Yoo BM, Cho SW, Cheong JY. Tenofovir-based rescue therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with suboptimal responses to adefovir with prior lamivudine resistance. J Med Virol. 2015;87:1532–1538. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn HJ, Song MJ, Jang JW, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK. Treatment efficacy and safety of tenofovir-based therapy in chronic hepatitis B: a real life cohort study in Korea. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovett GC, Nguyen T, Iser DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir in chronic hepatitis B: Australian real world experience. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:48–56. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcellin P, Zoulim F, Hézode C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in chronic hepatitis B: a 3-year, prospective, real-world study in France. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3072–3083. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4027-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen J, Heyne R, Mauss S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in chronic hepatitis B: a 3-year prospective field practice study in Germany. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3061–3071. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riveiro-Barciela M, Tabernero D, Calleja JL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of entecavir or tenofovir in a Spanish cohort of chronic hepatitis B patients: validation of the Page-B score to predict hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:784–793. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JM, Park JW, Choi BI. 2014 KLCSG-NCC Korea Practice Guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: HCC diagnostic algorithm. Dig Dis. 2014;32:764–777. doi: 10.1159/000368020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Corsa AC, Buti M, et al. No detectable resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in HBeAg+ and HBeAg-patients with chronic hepatitis B after 8 years of treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:68–74. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung GE, Cho EJ, Lee JH, et al. Tenofovir has inferior efficacy in adefovir-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients compared to nucleos(t)ide-naïve patients. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:66–73. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang DH, Xie YJ, Zhao NF, Pan HY, Li MW, Huang HJ. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is superior to lamivudine plus adefovir in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2746–2753. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SH, Cheon GJ, Kim HS, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate monotherapy is superior to entecavir-adefovir combination therapy in patients with suboptimal response to lamivudine-adefovir therapy for nucleoside-resistant HBV: a 96-week prospective multicentre trial. Antivir Ther. 2018;23:219–227. doi: 10.3851/IMP3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Lu X, Yang X, Ning Q. Comparison of the efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy versus tenofovir-based combination therapy in adefovir-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:20111–20122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoulim F, Bia kowska-Warzecha J, Diculescu MM, et al. Entecavir plus tenofovir combination therapy for chronic hepatitis B in patients with previous nucleos(t)ide treatment failure. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:779–788. doi: 10.1007/s12072-016-9737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon SC, Krastev Z, Horban A, et al. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at 240 weeks in patients with chronic hepatitis B with high baseline viral load. Hepatology. 2013;58:505–513. doi: 10.1002/hep.26277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitrinos KM, Corsa A, Liu Y, et al. No detectable resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate after 6 years of therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2014;59:434–442. doi: 10.1002/hep.26686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snow-Lampart A, Chappell B, Curtis M, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:763–773. doi: 10.1002/hep.24078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Prediction of virologic response to tenofovir mono-rescue therapy for multidrug resistant chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1027–1034. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lo AO, Wong VW, Wong GL, Tse YK, Chan HY, Chan HL. Efficacy of tenofovir switch therapy for nucleos(t)ide-experienced patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1190–1199. doi: 10.1111/apt.13185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coppolino G, Simeoni M, Summaria C, et al. The case of chronic hepatitis B treatment with tenofovir: an update for nephrologists. J Nephrol. 2015;28:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jung WJ, Jang JY, Park WY, et al. Effect of tenofovir on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e9756. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang HM, Hung CH, Lee CM, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir in nucleos(t)ide analog-naïve and nucleos(t)ide analog-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1307–1314. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lampertico P, Chan HL, Janssen HL, Strasser SI, Schindler R, Berg T. Review article: long-term safety of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in HBV-monoinfected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:16–34. doi: 10.1111/apt.13659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buti M, Gane E, Seto WK, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:196–206. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buti M, Riveiro-Barciela M, Esteban R. Long-term safety and efficacy of nucleo(t)side analogue therapy in hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2018;38(Suppl 1):84–89. doi: 10.1111/liv.13641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]