Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the effects of methotrexate (MTX) comedication added to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD) on disease activity measures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in routine care.

Methods

Patients with RA on treatment with either bDMARDs or conventional synthetic DMARDs were included in this prospective cohort study. The effect of (time-varying) combination therapy with bDMARD and MTX compared with bDMARD monotherapy was tested in longitudinal generalised estimating equation models using as outcomes: (1) the likelihood to be in remission according to the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (<2.6) and to the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) (0–30; ≤3), a patient-reported outcome measure about RA symptoms; and (2) DAS28-ESR and RAPID3 as continuous variables. All models were adjusted for potential confounders: age, gender, drugs for comorbidities (yes/no), oral steroids (yes/no) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (yes/no).

Results

In total, 330 patients were included (mean (SD) follow-up; 10.7 (9.7) months). Compared with bDMARD monotherapy, MTX combination therapy was significantly associated with a 55% higher likelihood to be in DAS28 remission, but not RAPID3 remission, over time. Combination therapy resulted in slightly, but statistically significant, lower levels of DAS28-ESR over time (β=−0.42 (95% CI −0.67 to − 0.17)), but not RAPID3 (β=−0.58 (95% CI −0.65 to 0.49)). The effect on DAS28-ESR was entirely explained by lower swollen joint counts and was persistent after correction for confounders.

Conclusion

These results give support to the policy that MTX should be continued in routine care patients with RA on biological therapy since this leads to better objective but not subjective clinical outcomes

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, methotrexate, DMARDs (biologic), DAS28, patient reported outcome measure (PROM)

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Randomised controlled clinical trials have already shown that the concomitant use of methotrexate (MTX) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on biologics is more efficient compared with monotherapy with biologics.

What does this study add?

Observational studies in RA investigating the added value of concomitant MTX over monotherapy with biologicals are scarce and yield contradictory conclusions.

This study adds to the knowledge that cotreatment with MTX in routine care patients with RA treated with biologicals lowers 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) over time and improves the likelihood to be in DAS28 remission.

Benefits were detected in non-patient-reported disease aspects like the swollen joint count instead of patient-reported aspects of the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3(RAPID3).

How might this impact on clinical practice?

By demonstrating the clinical significance of concomitant MTX use in routine care patients with RA, rheumatologists are helped with motivating patients to continue to use MTX combined with a biological in accordance with the treatment guidelines.

Introduction

Concomitant use of methotrexate (MTX) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treated with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD) has been shown to be more efficacious in mitigating these manifestations as compared with bDMARD monotherapy in various randomised clinical trials (RCT).1–4 The European League Against Rheumatism and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) have recommended this strategy.3 4

Still, there is evidence that many rheumatologists do not adhere to a strategy of MTX added to bDMARD in daily clinical practice.5 6 There are several reasons to explain non-adherence, such as poor tolerability and emerging contraindications,6 7 but this points to a discrepancy between clinical trials and usual practice. In fact, while RCT data on the efficacy of MTX added to bDMARD therapy are convincingly positive, evidence of such an effect in daily clinical practice is still scarce.

A few observational studies tried to bridge the findings in real-world clinical practice and RCTs on the efficacy data of bDMARDs in general.8–12 Thus far, observational research has yielded conflicting results regarding the possible added benefits of MTX on patients receiving bDMARDs and studies using longitudinal data are lacking.9 12 In this study, we aimed to evaluate the longitudinal effect of combining MTX with bDMARDs on disease activity measures over time in patients with RA from daily clinical practice.

Patients and methods

Patients

Consecutive adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of RA according to their treating rheumatologist that also fulfilled the ACR 1987 classification criteria13 were treated with conventional synthetic DMARD and/or bDMARDs. These patients were included in this prospective observational study that was executed in a large rheumatology centre in the Netherlands between April 2013 and April 2016. The local medical ethics committee reviewed and approved the study protocol. All patients provided informed consent before inclusion and were treated according to the routine care schedule.

Data collection

Patient’s age, gender, disease duration (in years) and the number of previous bDMARD failures (if any) were assessed at baseline. Data on disease activity measures, laboratory parameters and medication status were collected during routine visits every 3 months by rheumatologists and research nurses. A 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) based on four variables (tender joint count (TJC), swollen joint count (SJC), patient global assessment (PGA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) based (DAS28-ESR)) and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) were used in this study to reflect daily clinical practice.14 15 RAPID3 is a patient-driven questionnaire for RA outcome reporting on functioning (0–10), pain (0–10) and global health (0–10). RAPID3 (0–30) scores of >12, 6.1–12, 3.1–6 and ≤3 give high, moderate and low disease activity and remission, respectively. Prescription of comedication was used as a proxy for the presence of comorbidities and was collected using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System for the most frequently reported indications,16 namely cardiovascular diseases (ATC C*), type 2 diabetes mellitus (ATC C10*), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma (ATC R03*).17

Statistical analysis

The effect of combination treatment with MTX and bDMARDs as compared with bDMARD monotherapy on disease activity measures over time was tested in longitudinal linear/binomial (depending on the outcome) generalised estimating equation models with both the treatment and the outcome modelled as time-varying variables. Treatment was added to the models as a ‘dummy’ variable reflecting the four options encountered in clinical practice: (1) bDMARD+MTX; (2) bDMARD alone (reference); (3) MTX alone; and (4) none, but analyses focused on the comparison of interest (ie, combination treatment vs bDMARD monotherapy). The exchangeable ‘working’ correlation structure was used to take into account the repeated measures over time within patients. Disease activity was modelled in three complementary ways: (1) DAS28 and RAPID3 as continuous variables; (2) DAS28 and RAPID3 as binary definitions of remission (ie, <2.6 and ≤3, respectively); and (3) individual DAS28 components: that is, TJC (0–28), SJC (0–28), PGA (0–10) and ESR (mm/hour) as continuous variables. The effects of treatment on each outcome were tested in separate models, first with no adjustment (‘crude model’), and second after adjustment for variables a priori selected on clinical grounds as potential confounders (age (years), gender, use of drugs for comorbidities (yes/no), oral glucocorticoids (yes/no) and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID; yes/no)). Variables that vary over time (eg, treatment with NSAIDs) were modelled as such. All analyses were done with Stata V.15.

Results

Patients and follow-up

In total, 330 patients (1348 visits) were included. Overall, the mean (SD) follow-up time was 10.7 (9.7) months. The mean (SD) overall disease duration at baseline was 11.2 (9.6) years and failure of at least one previous bDMARD occurred in 20% of the patients. Patients on MTX comedication, compared with patients not on MTX, had at baseline lower mean DAS28-ESR (3.1 (1.3) with MTX vs 3.5 (1.4) without MTX; p=0.001) and lower RAPID3 scores (10.1 (6.2) with MTX vs 12.6 (6.0) without MTX; p<0.001). Other demographic and disease characteristics comparing the two groups are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics comparing patients treated and not treated with MTX at baseline

| All patients (n=330) |

MTX at baseline (n=148) |

No MTX at baseline (n=182) |

P value* | |

| Female gender, n (%) | 224 (67.9) | 95 (64.2) | 129 (70.9) | 0.200 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.0 (11.6) | 63.4 (11.6) | 60.9 (11.4) | 0.054 |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 11.2 (9.6) | 9.3 (7.8) | 12.9 (10.3) | 0.007 |

| ESR, mean (SD)† | 18.7 (17.6) | 19.3 (16.8) | 18.1 (18.5) | 0.60 |

| SJC (0–28), mean (SD)† | 2.3 (3.5) | 1.5 (2.7) | 3.2 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| TJC (0–28), mean (SD)† | 4.1 (5.5) | 3.0 (5.1) | 5.2 (5.8) | 0.004 |

| DAS28-ESR, mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.4) | 0.001 |

| RAPID3 total score (0–30), mean (SD) | 11.5 (6.2) | 10.1 (6.2) | 12.6 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| RAPID3 function (0–10), mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.9) | 2.1 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| VAS pain (0–10), mean (SD) | 4.3 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.5) | 0.004 |

| PGA (0–10), mean (SD) | 4.7 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| n drugs for comorbidities, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.7) | 0.390 |

| ≥1 drug for comorbidities, n (%) | 137 (41.5) | 56 (37.8) | 81 (44.5) | 0.220 |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 130 (39.4) | 53 (35.8) | 77 (42.3) | 0.230 |

| Oral steroids, n (%) | 117 (35.5) | 51 (34.5) | 66 (36.3) | 0.730 |

| MTX dosage, median (IQR), mg/week‡ | – | 15 (10–20) | – | |

| bDMARDs, n (%) | ||||

| No bDMARD§ | 104 (31.5) | 77 (52.0) | 27 (14.8) | |

| TNFi¶ | 185 (56.1) | 62 (41.9) | 123 (67.6) | <0.001 |

| No TNFi** | 41 (12.4) | 9 (6.1) | 32 (17.6) |

*χ2 test for categorical variables; independent samples t-test for continuous variables, statistical significant differences between treated and not treated with MTX at baseline are shown in bold

†n=213 patients. n (%) for categorical variables. Mean±SDs are presented above for normally distributed variables.

‡Subcutaneous MTX was used in 15% of the cases where MTX was used.

§Patients (n=27) neither on bDMARDs nor on MTX were treated with leflunomide, sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine.

¶TNFi includes: etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab.

**No TNFi includes: rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab.

DAS28-ESR, 28-joint Disease Activity Score (four variables, ESR based); ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PGA, patient global assessment; RAPID3, Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; VAS, visual analogue scale; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Longitudinal effect of combination therapy versus bDMARD monotherapy on disease activity over time

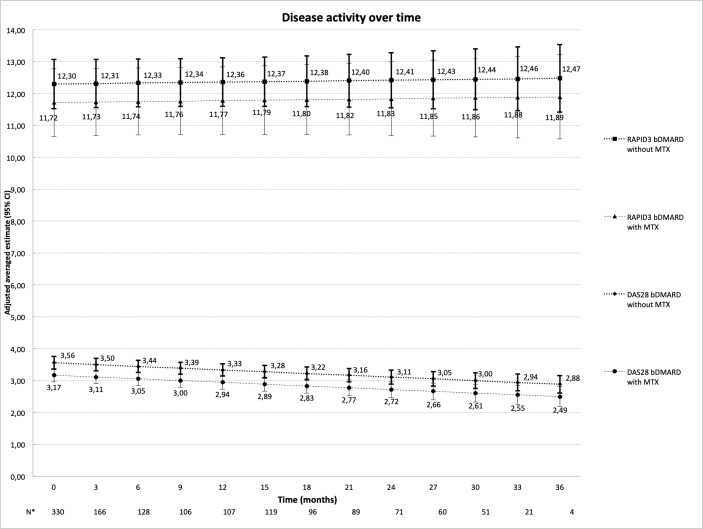

Overall, the adjusted estimates of the mean disease activity measured by DAS28 and RAPID3 over time are depicted in figure 1. MTX use in combination with bDMARDs was associated with lower levels of DAS28 compared with bDMARD monotherapy over time. On average, patients on combination treatment over time had 0.4 unit lower DAS28 than those treated with only bDMARDs, a small, yet statistically significant, difference that persisted after adjustment for age and other confounders (table 2).

Figure 1.

Adjusted estimates of DAS28 (95% CI) and RAPID3 (95% CI) scores over time based on multivariate models a priori adjusted for possible confounders: age, gender, drugs for comorbidities (1/0), oral glucocorticosteroids (1/0) and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. *Number of patients per visit. bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DAS28, 28-joint Disease Activity Score; MTX, methotrexate; RAPID3 (0–30), Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (three domains: functioning, pain, patient global)

Table 2.

Longitudinal effect of MTX plus bDMARD combination therapy compared with bDMARD monotherapy

| Outcome | DAS28* β (95% CI) |

RAPID3* β (95% CI) |

DAS28 <2.6† OR (95% CI) |

RAPID3 ≤3.0† β (95% CI) |

SJC* β (95% CI) |

ESR* β (95% CI) |

TJC* β (95% CI) |

PGA* β (95% CI) |

| Basic model‡ | −0.39 (−0.65 to −0.13) | −0.60 (−1.71 to 0.52) | 1.63 (1.10 to 2.42) | 1.17 (0.53 to 2.57) | −1.10 (−2.10 to −0.19) | −2.59 (−5.60 to 0.41) | −0.47 (−1.75 to 0.82) | −0.11 (−0.59 to 0.38) |

| Adjusted model§ | −0.42 (−0.67 to −0.17) | −0.58 (−0.65 to 049) | 1.55 (1.03 to 2.31) | 1.16 (0.55 to 2.42) | −0.91 (−1.77 to −0.06) | −1.90 (−4.87 to 1.08) | −0.52 (−1.84 to 0.80) | ¶ |

*Linear longitudinal generalised estimating equation (GEE) models were used for continuous outcomes; numbers shown are continuous status scores.

†Logistic longitudinal GEE models were used for binominal variables; numbers shown are ORs.

‡Non-adjusted model.

§Model of each component was adjusted for a priori selected possible confounders: age, gender, drugs for comorbidities (1/0), oral glucocorticosteroids (1/0) and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

¶No result; model failed to converge.

**Statistical significant results shown in bold.

DAS28, 28-joint Disease Activity Score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MTX, methotrexate; PGA, patient global assessment; RAPID3, Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

This benefit of MTX comedication was also seen with regard to the likelihood of achieving DAS28 remission, which was on average 55% higher with combination treatment. When looking into DAS28 individual components, the added benefit of MTX could only be demonstrated for the SJC but not for the ESR, TJC and PGA. RAPID3, both as a continuous variable and as a binary definition of remission, was not significantly different between the two different treatment strategies (table 2).

Discussion

In this prospective observational study we have shown that bDMARD patients with RA on MTX comedication fare objectively better than those on bDMARD monotherapy. This benefit was entirely explained by lower SJCs and did not extend to patient-reported measures of disease activity (RAPID3), nor to ESR and TJC, which adds to the recent suggestion that objectively measured and patient-reported outcomes should be separated when judging treatment effectiveness.18 19

Previous observational studies assessing the possible benefits/hazards of maintaining combination therapy in RA have yielded conflicting results. Gabay et al9 have shown that on average DAS28 was lower with combination treatment compared with bDMARD monotherapy, up to 4 years of follow-up. However, the same study has also shown no meaningful differences between the two strategies on the likelihood of being in DAS28 remission. Listing et al12 have previously shown a comparable result for combination versus monotherapy in a prospective study from the German biologics registerR. Other studies are less informative due to their cross-sectional design.8 9 Our study includes several paired measurements of DAS28 and RAPID3 collected over time in the same patients, and allows a better estimation of the long-term benefit of bDMARD therapy plus MTX comedication versus bDMARD therapy alone.

Of note, the positive effects of MTX comedication on disease activity measures were still present when taking into account the patients’ comorbidities, age, treatment with NSAIDs and oral glucocorticoids (ie, factors that might confound the association of interest). This finding further argues in favour of combination treatment even in more complex patients with comorbidities and long disease duration.

Interestingly, the effect of combination therapy on disease activity was only detected when using DAS28, but not RAPID3. Also, when looking at the various individual components of DAS28, the positive effect was only seen on the number of swollen joints (ie, an objective measure). This finding suggests that objective clinical outcome measures have merits in demonstrating treatment effects in daily clinical practice, and that only measuring subjective, patient-reported aspects of the disease, as is done with RAPID3, does not suffice despite strong messages by advocates.

Our study has some limitations worth noticing. The most important one is the expected a priori prognostic dissimilarity that may drive differences between the two strategies (confounding by indication). Among others, patients who are on MTX since they tolerate it may have better prognosis and thus better response to therapy. Tapering or discontinuation of bDMARD therapy in these patients could be considered. However, this is a common issue of all observational studies, that is, increase external validity (patients from clinical practice in whom, for example, comorbidities may have impaired cotreatment with MTX), at the cost of the internal validity (lack of random and blinded treatment allocation). Second, residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out, nevertheless after the adjustment for, arguably, the most important confounders the effect of MTX was still consistently seen in all models.

In conclusion, our results show patients with RA on biological therapy who have maintained their MTX dose have lower disease activity because they have less swollen joints.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the research nurses and medical doctors of the Zuyderland Medical Centre for seeing patients and collecting the data used in this study.

Footnotes

Presented at: This work was accepted at the EULAR 2018 conference as an extended abstract and for poster presentation.

Contributors: NWB, AS and RBML had full access to all of the data and take responsibility for data integrity and accuracy of data analysis. NWB, AS and RBML were involved in data processing and analysis. NWB, AS, RBML, PHvdK, RJ and RP were involved in the study design and writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical revising and the final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Zuyderland Medical Centre Medical Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available for sharing.

References

- 1.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The premier study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. 10.1002/art.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam JL, Takase-Minegishi K, Ramiro S, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review Informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1113–36. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American college of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Trends in the use of biologic agents among rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in the US Medicare program. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1743–51. 10.1002/acr.22055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1897–904. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salliot C, van der Heijde D. Long-term safety of methotrexate monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1100–4. 10.1136/ard.2008.093690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaltonen KJ, Ylikylä S, Tuulikki Joensuu J, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in randomized controlled trials and routine clinical practice. Rheumatology 2017;177:kew467–35. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabay C, Riek M, Scherer A, et al. Effectiveness of biologic DMARDs in monotherapy versus in combination with synthetic DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis: data from the swiss clinical quality management registry. Rheumatology 2015;54:1664–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zink A, Strangfeld A, Schneider M, et al. Effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis in an observational cohort study: comparison of patients according to their eligibility for major randomized clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3399–407. 10.1002/art.22193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kievit W, Fransen J, Oerlemans AJ, et al. The efficacy of anti-TNF in rheumatoid arthritis, a comparison between randomised controlled trials and clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1473–8. 10.1136/ard.2007.072447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Rau R, et al. Clinical and functional remission: even though biologics are superior to conventional DMARDs overall success rates remain low–results from RABBIT, the German biologics register. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R66 10.1186/ar1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. 10.1002/art.1780310302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Heijde DM, van 't Hof MA, van Riel PL, et al. Judging disease activity in clinical practice in rheumatoid arthritis: first step in the development of a disease activity score. Ann Rheum Dis 1990;49:916–20. 10.1136/ard.49.11.916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Bergman MJ, et al. RAPID3 (routine assessment of patient index data) on an MDHAQ (multidimensional health assessment Questionnaire): agreement with DAS28 (disease activity Score) and CDAI (clinical disease activity index) activity categories, scored in five versus more than ninety seconds. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:181–9. 10.1002/acr.20066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:62–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. Oslo, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira R, Wit de. Dual target strategy: a proposal to mitigate the risk of overtreatment and enhance patient satisfaction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landewé RBM. Response to: ’Dual target strategy: a proposal to mitigate the risk of overtreatment and enhance patient satisfaction in rheumatoid arthritis' by Ferreira et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2018. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214221 [Epub ahead of print 20 Aug 2018]. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]