Abstract

We characterized 419 Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates collected between 2011 and 2017 in Osaka prefecture of Japan. This analysis revealed high prevalence of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) in Osaka during 2011 and 2014 with annual detection rates of MRMP strains between 71.4% and 81.8%. However, in 2015 and after, the detection rate of MRMP decreased significantly and did not exceed 50%. Genotyping of the p1 gene of these isolates showed that most of MRMP strains harbored type 1 p1 gene. In contrast, strains expressing p1 gene type 2 or its variant were largely macrolide-susceptible M. pneumoniae (MSMP) strains. There was a strong correlation between p1 gene genotype and the presence of mutations conferring macrolide resistance in M. pneumoniae isolated in Osaka. These results indicate that lower incidence of MRMP strains in Osaka from 2015 was associated with the relative increase of p1 gene type 2 lineage strains. During these experiments, we also isolated three M. pneumoniae strains that showed irregular typing pattern in the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis of the p1 gene. Two of these strains harbored new variants of type 2 p1 gene and were designated as type 2f and 2g. The remaining strain with an irregular typing pattern had a large deletion in the p1 operon.

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common bacterial cause of pneumonia and bronchitis in humans [1–3]. Pneumonia caused by this organism accounts for a significant part of community-acquired pneumonia cases worldwide and is particularly common in children and young adults [1,3]. In most cases, symptoms of M. pneumoniae pneumonia are relatively mild. However, serious cases with various complications that require hospitalization are not uncommon [4]. Macrolide resistance (MR) is a recent global concern for clinical treatment of M. pneumoniae pneumonia [5,6]. Macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) is highly prevalent in Asian countries, including China, Korea, and Japan. Moreover, it is gradually increasing in other areas of the world as well [2,7,8].

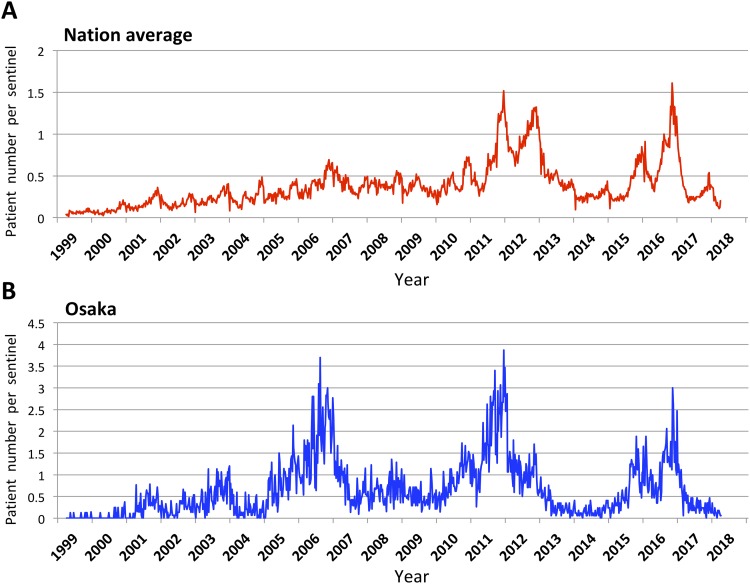

Periodical increases in the number of patients with M. pneumoniae pneumonia in 3–7-year cycles have been reported in many epidemiological studies from various parts of the world [9–14]. In Japan, large epidemics of M. pneumoniae pneumonia were observed recently in 2011, 2012, 2015, and 2016 by the national epidemiological surveillance of infectious diseases (Fig 1). In the epidemic in 2011 and 2012, high prevalence of MRMP strains among clinical isolates from wide areas of Japan was also reported [15–17].

Fig 1. Surveillance of pneumonia cases associated with M. pneumoniae infection in Japan.

Weekly cases of pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae in Japan from April 1999 to present. The graphs are based on the data of the National Epidemiological Surveillance of Infectious Diseases (NESID). (A) Nation average is based on the report from about 500 sentinels. (B) The data of Osaka is based on the report from about 7 to 17 sentinels depending on the year. Also see S1 Table for detail. The latest data are available from the website of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/ja/idwr.html).

Currently, the reason for the periodic occurrence of M. pneumoniae pneumonia epidemics is not fully understood. In addition, it is unclear whether the emergence and wide spreading of MRMP strains affects epidemiological patterns of M. pneumoniae pneumonia. For better understanding of these aspects of M. pneumoniae infections, it is important to isolate M. pneumoniae strains from patients continuously and to examine their genetic properties. In this study, M. pneumoniae isolates were collected from 419 patients with respiratory infections between 2011 at 2017 in Osaka prefecture, the second largest metropolitan area in Japan (population of Osaka prefecture is approximately 9 million). We report here the results of MR analysis and genotyping of these M. pneumoniae isolates.

Materials and methods

Isolation of M. pneumoniae

From July 2011 to March 2017, throat swabs were collected from patients suspected of M. pneumoniae infection in six pediatric clinics and nine pediatrics departments of hospitals in Osaka prefecture. The swabs were collected based on the approvals of the Ethics Committee of the Osaka Institute of Public Health (1602–05 and 1310–02). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all subjects. The swabs were kept in BD Universal Viral Transport System (Nippon Becton Dickinson Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and cryopreserved until further examination. The specimens were inoculated into both diphasic mycoplasma medium and PPLO broth [18] and cultured at 37 °C for 2 months. Culture-positive specimens during the culture period were stored, and identification of M. pneumoniae was performed by PCR [19].

Detection of MR mutations in the 23S rRNA gene

MR of M. pneumoniae isolates was determined by sequencing of the domain V region of the 23S rRNA gene. PCR primers Myco23S-F (5′-TCTCGGCTATAGACTCGGTGA-3′, positions 1998–2018 of the 23S rRNA gene) and Myco23S-R (5′-TAAGAGGTGTCCTCGCTTCG-3′, positions 2673–2692) were designed and used to amplify the region that contains the known MR mutation sites (in mycoplasma numbering, positions 2063, 2064, 2067, and 2617 of 23S rRNA gene). The amplified PCR products were sequenced by using the same primers on an ABI 3130 genetic analyzer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to detect the mutations.

P1 gene typing of M. pneumoniae isolates

Isolate p1 gene (MPN141) types were determined by using the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) typing method [20–22]. Briefly, genomic DNA of the isolates was extracted from the PPLO culture medium using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan). Two pairs of primers (ADH1-ADH2 and ADH3-ADH4) were used to amplify the polymorphic regions of the p1 gene (containing RepMP4 or RepMP2/3 regions) by PCR from genomic DNA. PCR products were digested with HaeIII restriction endonuclease and electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel. After gel staining, RFLP patterns of the PCR products were compared to determine p1 types.

Sequencing analysis of the p1 operon region of new variant strains

The region containing the entire p1 gene of the new variant strains M282 and K708 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using primers P1-200F (5′-GGCTGTTCTTTATAGAAGAG-3′) and P1+100R (5′-TGGTCTTGGAGGAGGTAGGT-3′). The orf6 gene (MPN142) of strains M282 and K708 was also amplified by PCR using primers ORF6-F (5′-GCGCCAAAACGCTTGAAACA-3′) and OP-R1 (5′-TTGCACTAGGAAGGTAATGT-3′). The p1 operon region of strain M241 was amplified by using forward primers OP-F1 (5′-TACTACTTACAACTCTTTGT-3′) or ADH3 (5′-CGAGTTTGCTGCTAACGAGT-3′) and the reverse primer 23e-R1 (5′-AAGAGGTGAAGCCTCGCTAA-3′). Amplified DNA fragments were sequenced by the primer-walking strategy using an ABI 3130xl genetic analyzer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The primer sequences used for the primer-walking of the p1 operon region are listed in S2 Table.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the Fisher’s exact test with a significance level of α = 0.05 (P < 0.05) by using R software version 3.2.3.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

Nucleotide sequences of p1 genes of type 2f strain M282 and type 2g strain K708 were deposited into DDBJ/ENA/GenBank databases under the accession numbers LC311244 and LC385984, respectively. The sequences of the orf6 gene of strains M282 and K708 were deposited under the accession numbers LC390170 and LC420352, respectively. The sequence of the p1 operon of strain M241 was also deposited under the accession number LC390171.

Results

Variable annual detection rate of MRMP strains in Osaka prefecture

In this study, a total of 419 M. pneumoniae strains were isolated from patients with suspected M. pneumoniae infection in Osaka prefecture between 2011 and 2017. Table 1 shows the numbers of isolated M. pneumoniae strains per annum. Numbers of isolates differed from year to year, and their isolation frequency correlated well with the annual prevalence of M. pneumoniae pneumonia in Osaka prefecture (Fig 1).

Table 1. Number of M. pneumoniae isolates collected in this study and macrolide resistance rate.

| Year | Number of isolates | Number of MR isolates | MR rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 64 | 49 | 76.6 |

| 2012 | 11 | 9 | 81.8 |

| 2013 | 7 | 5 | 71.4 |

| 2014 | 15 | 11 | 73.3 |

| 2015 | 157 | 65 | 41.4 |

| 2016 | 157 | 67 | 42.7 |

| 2017 | 8 | 4 | 50.0 |

| Total | 419 | 210 | 50.1 |

All MR isolates harbored A2063G mutation except for one isolate that had A2063T mutation. The isolate that harbored A2063T was obtained in 2013. MR: macrolide-resistance. Also see S3 Table.

To determine the prevalence of MR in these isolates, we analyzed the domain V region of the 23S rRNA gene in all isolates by PCR and DNA sequencing. MR mutations were found in 210 out of 419 isolates (50.1%). The fraction of MRMP strains was higher than 70% between 2011 and 2014 (71.4–81.8%), whereas in 2015 and after, it decreased significantly to 41.4–50% (P < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 1). All of MRMP isolates but one (209/210, 99.5%) harbored the A2063G transition mutation, the most frequent MR mutation reported to date [7]. One strain isolated in 2013 had A2063T transversion (Table 1).

We also compared the fractions of isolates with MR in clinics (primary medical institutions) with that in hospitals (higher order medical institutions) in 2015 and 2016 to establish if MR incidence depended on the scale of the medical institutions (Table 2). In 2015, the fractions of MR isolates were significantly higher in hospitals (59/110, 53.6%) than in clinics (6/47, 12.8%; P < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Similar tendency was also observed in 2016. The fraction of MR isolates in 2016 was 45.9% (62/135) in hospitals and 22.7% (5/22) in clinics (P = 0.061, Fisher’s exact test). Thus, the incidence of MR in isolates from hospitals was higher than that in isolates from clinics.

Table 2. Differences in the rate of macrolide resistance of M. pneumoniae isolates between clinics and hospitals.

| Year | Origin of isolates | Number of isolates | Number of MR isolates | MR Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Clinic | 47 | 6 | 12.8 |

| Hospital | 110 | 59 | 53.6 | |

| 2016 | Clinic | 22 | 5 | 22.7 |

| Hospital | 135 | 62 | 45.9 |

MR: macrolide resistance

Relationship between p1 gene type and resistance of M. pneumoniae isolates to macrolides

By using the PCR-RFLP method [22], we carried out p1 gene typing of 419 isolates. As a result of this typing analysis, 223 isolates were classified as type 1 (53.2%), 102 isolates were type 2 (24.3%), 6 were type 2a (1.4%), 1 was type 2b (0.2%), 84 were type 2c (20%), and 3 were non-typable (0.7%) (Table 3). The p1 gene type 1 isolates were highly prevalent between 2011 and 2014 (71.4–90.9%), however after this period, type 2 and type 2c isolates increased significantly (P < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Therefore, the relative isolation rate of type 1 M. pneumoniae strains decreased to 43.3–62.5% between 2015 and 2017 (Table 3).

Table 3. Annual distribution of p1 gene typing results in M. pneumoniae.

| Year | p1 gene type | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2a | 2b | 2c | Non-typable* | ||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| 2011 | 53 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 64 |

| (82.8) | (9.4) | (1.6) | (6.3) | ||||

| 2012 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| (90.9) | (9.1) | ||||||

| 2013 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| (71.4) | (28.6) | ||||||

| 2014 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 15 |

| (73.3) | (26.7) | ||||||

| 2015 | 68 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 157 |

| (43.3) | (29.9) | (26.8) | |||||

| 2016 | 71 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 3 | 157 |

| (45.2) | (35) | (17.8) | (1.9) | ||||

| 2017 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| (62.5) | (37.5) | ||||||

| Total | 223 | 102 | 6 | 1 | 84 | 3 | |

| % | (53.2) | (24.3) | (1.4) | (0.2) | (20) | (0.7) | 419 |

We then examined whether p1 typing results correlated with the presence of MR mutations in isolates and found that the presence of MR mutations in isolates was highly dependent on p1 gene type. Most of type 1 isolates harbored MR mutations (204/223 isolates, 91.5%). In contrast, only one type 2 (1/102, 1%) and five type 2c (5/84, 6%) isolates harbored A2063G mutation (Table 4). The total isolates with MR mutation in type 2 lineage (2, 2a, 2b, and 2c) was 3.1% (6/193). Thus, the presence of MR mutations was strongly determined by the p1 type (between type 1 and 2 lineages) (P < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 4. Distribution of MR mutations in M. pneumoniae isolates of different p1 types.

| Macrolide-resistant mutations | p1 type | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2a | 2b | 2c | Non-typable* | ||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| None | 19 | 101 | 6 | 1 | 79 | 3 | 209 |

| (8.5) | (99) | (100) | (100) | (94) | (100) | ||

| A2063G | 203 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 209 |

| (91) | (1) | (6) | |||||

| A2063T | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| (0.5) | |||||||

| Total | 223 | 102 | 6 | 1 | 84 | 3 | 419 |

| Total MR (%) | (91.5) | (1) | (0) | (0) | (6) | (0) | (50.1) |

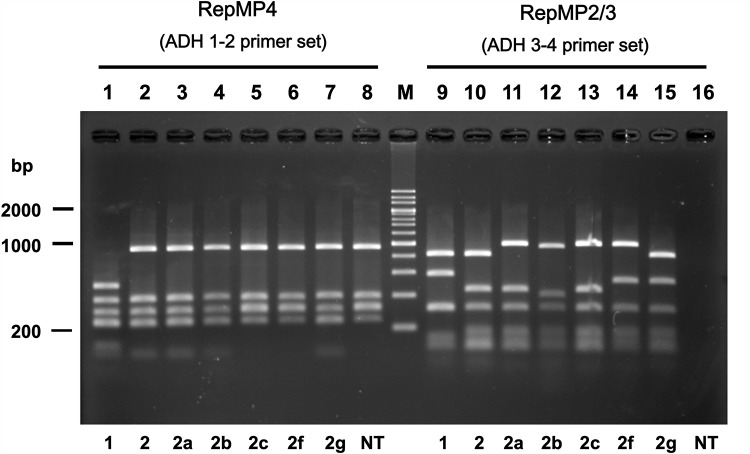

Three non-typable p1 isolates were collected in 2016 and designated as strains M241, M282, and K708 (Tables 3 and 4). In the RepMP4 region analysis, these strains exhibited known PCR-RFLP patterns. The patterns of strains M282 and M241 were identical to that of type 2c strains (Fig 2, lanes 6 and 8). Furthermore, the RepMP4 pattern of strain K708 was identical to that of type 2, 2a, or 2b strains (Fig 2, lane 7). RepMP2/3 region patterns of these strains were however different from those of known strain types (Fig 2, lanes 14–16). RepMP2/3 patterns of strains M282 and K708 were novel (Fig 2, lanes 14 and 15). The RepMP2/3 region of strain M241 could not be analyzed due to the lack of PCR amplification when ADH3 and ADH4 primers were used (Fig 2, lane 16).

Fig 2. PCR-RFLP typing of the p1 gene.

M. pneumoniae isolates from 419 patients in this study were classified into eight p1 gene types by PCR-RFLP analysis. The RFLP patterns of the RepMP4 region (lanes 1 to 8) and the RepMP2/3 region (lanes 9 to 16) that represent eight p1 gene types are shown. p1 gene types corresponding to RFLP patterns are indicated below the gel image. NT indicates non-typable strain M241 (see text). Lane M contains size markers (200 bp ladder). Type 2b is also referred as type 2V in other reports [26,49]. The original electrophoresis image is shown in S3 Fig).

Characterization of the p1 operon region of M241, M282, and K708 strains

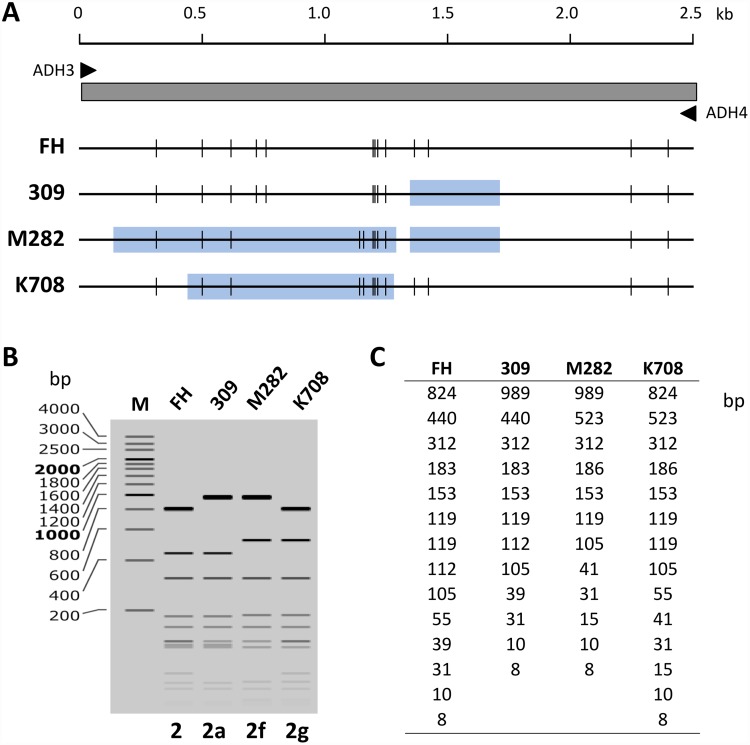

To establish the reason for the irregular RFLP patterns of strains M241, M282, and K708 (Fig 2), we analyzed the p1 gene region of these strains by sequencing. The entire p1 gene regions of strains M282 and K708 were amplified from the genomic DNA by PCR and sequenced. These analyses identified novel sequence variations in the RepMP2/3 region of strains M282 and K708. The theoretical HaeIII digestion patterns of ADH3-4 amplicon were in good agreement with experimental data (Fig 2, lanes 14 and 15; Fig 3). In the p1 gene region of strain K708, a minor variation was also identified in the RepMP4 region (S1 Fig). This minor variation in the RepMP4 region did not affect the HaeIII site and RFLP pattern. The p1 genes of M282 and K708 strains are thought to have originated from type 2c and type 2 p1 genes, respectively. However, novel variation sequences of these genes were partially similar to the type 1 p1 gene sequence (S1 Fig). We therefore designated the p1 genes of strains M282 and K708 as type 2f and 2g, respectively (GenBank accession nos. LC311244 and LC385984). These variations were presumably generated by gene conversion-like DNA recombination between RepMP2/3 sequences within and outside of the p1 operon [23,24] (S1 Fig).

Fig 3. Novel p1 gene sequence variations in strains M282 and K708.

(A) Schematic diagram of the PCR amplicons obtained using the primers ADH3 and ADH4, containing RepMP2/3 region of the p1 gene. Predicted HaeIII sites within the amplicons from strains FH (type 2), 309 (type 2a), M282 (type 2f), and K708 (type 2g) are shown. Light blue boxes indicate the regions of sequence variations compared to that of the type strain FH. (B) Simulated pattern of 2% agarose electrophoresis of HaeIII-digested amplicon fragments predicted by using the p1 gene sequences (GenBank accession nos. CP010546, AP012303, LC390170 and LC385984). The pattern was calculated by using SnapGene software version 4.2.3 (Snapgene.com). (C) Theoretical size of HaeIII-digested amplicon fragments.

The recently obtained M. pneumoniae whole genome sequence datasets suggest that p1 gene type 2b and 2c strains have common sequence variations in the orf6 gene (MPN142), which differentiate these strains from other type 2 strains [25,26]. Therefore, we have sequenced the orf6 region of strains M282 and K708 and revealed that the type 2f strain M282 had a novel, 90-bp long sequence variation at the 5′ end of the orf6 gene (GenBank accession no. LC390170) (S1 Fig). Furthermore, the orf6 sequence of the type 2f strain K708 (GenBank accession no. LC420352) was identical to that of the type 2 strain FH (GenBank accession no. CP017327) (S1 Fig).

The p1 gene of strain M241 could not be amplified with PCR primers used for the analysis of M282 and K708 p1 genes. Because a large sequence change was expected at the 3′ end of M241 p1 gene, we designed several PCR primers that correspond to downstream of the p1 operon. Using one of these reverse primers, designated as 23e-R1, which was specific to the site about 2.5 kb downstream of the p1 operon (downstream of the orf6 gene), we achieved amplification of M241 p1 gene region. The PCR product size was about 6.8 kb shorter than expected (S2 Fig). Sequencing of the PCR product revealed that a 6.8-kb deletion occurred in the p1 operon of M241 strain due to DNA recombination between the RepMP2/3 region in the p1 gene and another RepMP2/3 located downstream of the p1 operon (GenBank accession no. LC390171). This deletion caused a loss of the ADH4 primer binding site and entire orf6 gene (S2 Fig). As expected from these results (truncation of the 3′ end of the p1 gene and loss of the orf6 gene), strain M241 had no cytadherence activity in the conventional hemadsorption assay [27,28].

Discussion

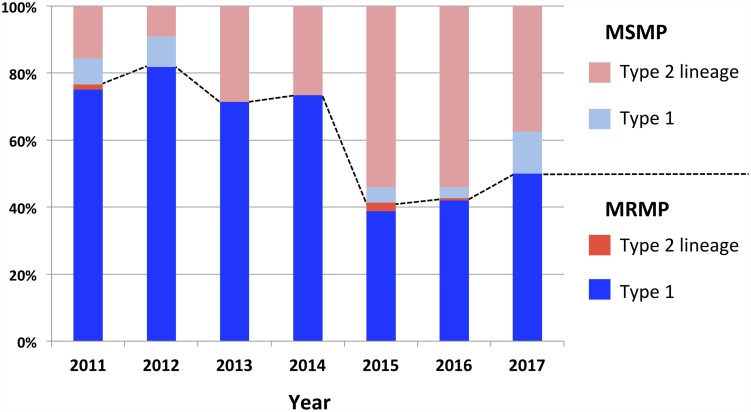

In this study, we collected 419 M. pneumoniae isolates in Osaka prefecture between 2011 and 2017, established their p1 gene type, and identified MR-conferring mutations. Several previous studies reported that the dominant p1 type of M. pneumoniae clinical isolates in Japan was type 1 since 2003 [1,29]. This was also true in the large epidemic period in 2011 and 2012 [15,30]. Our study in Osaka was consistent with these previous reports, showing high prevalence of type 1 isolate between 2011 and 2014 (Table 2). However, after that period, type 2 lineage (type 2 and 2c) isolates increased rapidly and comprised more than half of all isolates in 2015 and 2016 (Table 2). Interestingly, in contrast to type 1 isolates that are largely MRMP strains, most of type 2 lineage isolates were MSMP strains (Table 4 and Fig 4). Therefore, the total ratio of MR strains among M. pneumoniae isolates in Osaka decreased in 2015 and thereafter (Table 1 and Fig 4). Low prevalence of MR in p1 type 2 strains has already been reported in M. pneumoniae isolates in Yamagata prefecture of northern Japan between 2004 and 2014 [16,30]. In addition, a recent epidemiological study of M. pneumoniae pneumonia in Japan reported nationwide decrease of MRMP strains after 2013, although p1 typing was not performed [31]. In that nationwide report, publication of treatment guidelines for M. pneumoniae pneumonia is mentioned as one of the major factors for the decrease of MRMP strains in Japan after 2013. With these guidelines published in 2011, clinicians may have started paying more attention to the appropriate use of macrolides to prevent the spread of MRMP. This may partly explain the decrease of MRMP strains in Japan after 2013. However, as shown in our study in Osaka, we consider that the increase in MSMP strains with p1 gene type 2 lineages was another major factor for the decrease of MR rate in Japan.

Fig 4. Annual rates of isolation of macrolide-resistant M. pneumoniae (MRMP) and macrolide-susceptible M. pneumoniae (MSMP) strains in Osaka in 2011–2017.

The fractions of p1 gene type 1 and type 2 lineage MRMP isolates are shown in blue and red, respectively. The fractions of p1 gene type 1 and type 2 lineage MSMP isolates are shown in light blue and pink, respectively. Dotted line indicates the boundary between MRMP and MSMP strains. Also see S4 Table.

The real mechanism underlying the correlation between MR and p1 gene type revealed in this study is unknown, however the probable reasons may be as follows. Type 2 M. pneumoniae was frequently isolated in Japan in 1990s [1,29]. Therefore, in early studies of MR of M. pneumoniae in Japan, no correlation between MR and p1 gene type was noted [32,33]. However, after 2003, type 1 M. pneumoniae became dominant, and this continued for about 10 years in Japan [1,15,16,29,30]. Most of M. pneumoniae pneumonia cases in that period might have been caused by type 1 M. pneumoniae. In this situation, chemotherapy using macrolides might select resistant strains from type 1 M. pneumoniae rather than type 2 lineage. Then, type 1 MRMP strains spread widely in the community until the epidemic period in 2011 and 2012. However, after then, the occurrence of M. pneumoniae type 2 lineage increased, probably because of the type shift phenomenon of the pathogen as a result of interactions between antigenicity of pathogens and immunological status of human population [1,29,34]. At present, type 2 lineage strains isolated from patients are still considered as being macrolide-sensitive. To assess these hypotheses, it is particularly important to continue surveillance and carry out genetic characterization of M. pneumoniae isolates to establish whether the number of MRMP isolates of p1 type 2 lineage increases after this point.

Correlation between MR and p1 type of M. pneumoniae has also been reported in studies of recent clinical isolates in China and Korea [35–39]. Probably, the clinical usage of macrolides and dominant p1 gene type trend in these countries are similar to those in Japan. Geographic location may also affect distribution of similar M. pneumoniae strains. However, MR and p1 type did not correlate closely in the studies performed in the United States and other countries [40–42]. In the United States, the MR rate did not change over time despite fluctuations in dominant p1 type [42,43]. The lack of correlation may be attributed to the generally low MR rate in these countries at the time of observation (under 30%), similar to the situation in Japan around year 2000 [32,33]. The preservation of the low MR rate of M. pneumoniae in these countries may be related to the frequency of macrolide usage in clinical treatments in these countries. The selection of MRMPs with specific p1 type has not yet occurred in these countries.

In Japan, macrolides are recommended as first-line drugs for the treatment of M. pneumoniae pneumonia [1]. If macrolides are not effective, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are recommended as second-line drugs. However, the use of tetracyclines in children younger than 8 years old presents a significant risk because of adverse effects. There is also an ongoing debate regarding the therapeutic effects of fluoroquinolones (tosufloxacin) used for the treatment of M. pneumoniae pneumonia in children [17,44]. Therefore, providing updated information on the fraction of MRMP isolates is important for effective treatments of diseases by clinicians. However, the fraction of MRMP strains inferred by the epidemiological studies may be different from the actual prevalence of MR in the community, depending on the study design. In other words, MR rate may be higher in large hospitals than in clinics because M. pneumoniae pneumonia patients who do not recover after the treatment with macrolides and exhibit severe symptoms tend to transfer from clinics to larger hospitals. In these serious cases, pathology is usually caused by MRMP strains. Therefore, we compared the fractions of MR isolates in clinics and in hospitals in 2015 and 2016. As expected, the MR rate in hospitals was higher than that in clinics (Table 2). However, the MR rate in clinics rather than in hospitals may better reflect actual prevalence of MRMP strains in the community.

In this study, we have identified new type 2 variant p1 genes designated as type 2f and 2g (GenBank accession nos. LC311244 and LC385984). These type 2 variants partially encompassed type 1 p1 gene sequences derived from the RepMP4 sequence outside the p1 operon (S1 Fig). New p1 variant strains may appear spontaneously at a low frequency in the population of M. pneumoniae due to shuffling of RepMP sequences mediated by gene conversion-like DNA recombination [23,24,45]. However, the fate of new p1 strains, i.e., whether they become a major subtype or disappear, may depend on natural selection, survival of the fittest, or chance. It is empirically known that p1 types of isolates do not change easily during repeated passages in laboratory. The stability of p1 type may be related to the low level of DNA recombination in this bacterium [46,47]. Therefore, we believe that type 2f and 2g strains isolated in this study were the cause of pneumonia and were not created during culture isolation, although we did not confirm this by direct p1 typing of clinical specimens. Furthermore, another isolate, M241, displayed no cytadherence activity due to a large deletion in the p1 operon (S2 Fig). Cytadherence is an essential factor for M. pneumoniae pathogenesis, therefore, there is a possibility that M241 was not involved in the disease onset and was selected or emerged during culture isolation. Strain S355 isolated in China (GenBank accession no. CP013829) also had a large deletion similar to that in M241 in the p1 operon probably due to DNA recombination between RepMP4 sequences, although the phenotype of that strain has not been described [48]. Spontaneous loss of functional p1 operon by recombination between RepMP sequences may occur more frequently than generation of new p1 variants in the population of M. pneumoniae (S2 Fig).

In this study, we have characterized 419 M. pneumoniae isolates collected in Osaka between 2011 and 2017. This analysis revealed a correlation between the decrease of MRMP strains and increase of p1 gene type 2 lineage M. pneumoniae in Japan in recent years. The limitation of this study was the highly variable number of strains isolated in different years, which ultimately depended on the annual number of pneumonia patients (Fig 1 and Table 1). This made the comparison of MR rate and p1 type data between different years complicated. However, information obtained in our present analyses may be useful for future epidemiological studies. Continuous efforts for the collection of M. pneumoniae isolates and genotyping analysis are important for better understanding of epidemiology of M. pneumoniae infections.

Supporting information

(A) Schematic illustration of the p1 operon region and comparison of 11 p1 subtypes. Three light blue arrows indicate orf4 (MPN140), p1 (MPN141), and orf6 (MPN142) genes of the p1 operon. The approximate size of the operon is shown above in base pairs (bp). The positions correspond to P40 and P90 proteins are shown in the orf6 gene. Pink, green, and blue rectangles below the p1 and orf6 genes indicate approximate positions of RepMP repetitive sequence regions (RepMP4-c, RepMP2/3-d, and RepMP5-c). Black rectangles indicate approximate positions of sequence variations of p1 and orf6 genes using type 2 strain FH as reference. Probable origins of the variation of these sequences (suffixes of RepMPs are identical to the variations) are indicated next to gray rectangles (also see panel B). Representative strains that harbor genes of the corresponding subtype are indicated on the left. Accession numbers of the subtype sequences are shown on the right. Type 2b is also referred to as type 2V in other reports [26,49,50]. Sequence information of the orf6 gene of the type 2c2 strain P53 was kindly provided by Dr. Fei Zhao of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The orf6 sequence of the type 2e strain Mp100 has not yet been reported [51]. (B) Distribution of RepMP regions in M. pneumoniae genome. Approximate positions of 8 RepMP4, 12 RepMP2/3, and 8 RepMP5 regions in M. pneumoniae genome are indicated by colored boxes. Two RepMP2/3 regions (RepMP2/3-k and -l) were newly identified during genome sequencing analysis of KCH-402 and KCH-405 strains (GenBank accession nos. AP017318 and AP017319) [25]. Suffixes of RepMP regions (-a to -k) are based on the nomenclature system proposed by Spuesens et al. previously [24,45].

(TIF)

The light blue arrows indicate the p1 and orf6 genes. The p1 gene of strain M241 had a truncation at the C-terminus due to DNA recombination between the repetitive sequence regions RepMP2/3-d and RepMP2/3_e (also see S1B Fig). Small orange arrows indicate approximate positions of PCR primer binding sites (ADH1, ADH2, ADH3, ADH4, and 23e-R1). The lower right panel is an electrophoresis pattern in 0.8% agarose gel of DNA fragments obtained as PCR products from FH and M241 strain genomes by using ADH3 and 23e-R1 primers. The regions corresponding to the PCR products are indicated by red arrows. A faint 1.9 kb band in FH strain suggests a presence of similar recombination event in growth population of FH strain.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(PDF)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Sadasaburo Asai of the Asai Children’s Clinic, Dr. Atsuko Naka of the Hata Pediatric Clinic, Dr. Tohru Matsushita of the Matsushita Kids Clinic, Dr. Keiji Nakano of the GG Kids Clinic, Dr. Yoshihiro Takeda of the Takeda Pediatric Clinic, Chieko Kushibiki of the Kishiwada Tokushukai Hospital, Dr. Urara Kohdera of the Nakano Children’s Hospital, Dr. Masashi Shiomi of the Aizenbashi Hospital, Dr. Naoki Hata of the PL Hospital, Dr. Yoshiaki Harada of the Komatsu Hospital, Dr. Eri Hayashi of the Izumi City General Hospital, Dr. Koji Matsuzaki of the Suita Municipal Hospital, Dr. Hiroshi Katayama of the Saiseikai Suita Hospital, and Dr. Fumiyoshi Yamaue of the Yamaue Pediatric Clinic for providing clinical specimens. We thank Kayoko Mizutani, Michiko Ishinabe, and Takahiro Yamaguchi for experimental support. We are also grateful to Dr. Fei Zhao of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the sequence of the orf6 gene of M. pneumoniae strain P53.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 25460834, Dr. Chihiro Katsukawa; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development 18jk0210004j0101, Dr. Tsuyoshi Kenri; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development 17jk0210004j0001, Dr. Keigo Shibayama; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development 16jk0210004j0001, Dr. Keigo Shibayama; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development 15jk0210004h0027, Dr. Keigo Shibayama; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare H26-Kokui-Shitei-001, Dr. Keigo Shibayama. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yamazaki T, Kenri T. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections in Japan and Therapeutic Strategies for Macrolide-Resistant M. pneumoniae. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:693 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00693 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waites KB, Xiao L, Liu Y, Balish MF, Atkinson TP. Mycoplasma pneumoniae from the Respiratory Tract and Beyond. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2017;30(3):747–809. 10.1128/CMR.00114-16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parrott GL, Kinjo T, Fujita J. A Compendium for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:513 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00513 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izumikawa K. Clinical Features of Severe or Fatal Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:800 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00800 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki N, Narita M, Yamada S, Izumikawa K, Umetsu M, Kenri T, et al. Characteristics of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains isolated from patients and induced with erythromycin in vitro. Microbiology and immunology. 2001;45(8):617–20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morozumi M, Takahashi T, Ubukata K. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae: characteristics of isolates and clinical aspects of community-acquired pneumonia. Journal of infection and chemotherapy: official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2010;16(2):78–86. 10.1007/s10156-009-0021-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereyre S, Goret J, Bebear C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Current Knowledge on Macrolide Resistance and Treatment. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:974 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00974 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer Sauteur PM, Unger WW, Nadal D, Berger C, Vink C, van Rossum AM. Infection with and Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Children. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:329 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00329 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foy HM, Kenny GE, Cooney MK, Allan ID. Long-term epidemiology of infections with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1979;139(6):681–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind K, Bentzon MW. Changes in the epidemiological pattern of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Denmark. A 30 years survey. Epidemiology and infection. 1988;101(2):377–86. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rastawicki W, Kaluzewski S, Jagielski M, Gierczyski R. Epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Poland: 28 years of surveillance in Warsaw 1970–1997. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 1998;3(10):99–100. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eun BW, Kim NH, Choi EH, Lee HJ. Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Korean children: the epidemiology of pneumonia over an 18-year period. The Journal of infection. 2008;56(5):326–31. 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.02.018 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenglet A, Herrador Z, Magiorakos AP, Leitmeyer K, Coulombier D, European Working Group on Mycoplasma pneumoniae surveillance. Surveillance status and recent data for Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in the European Union and European Economic Area, January 2012. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2012;17(5). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RJ, Nguipdop-Djomo P, Zhao H, Stanford E, Spiller OB, Chalker VJ. Mycoplasma pneumoniae Epidemiology in England and Wales: A National Perspective. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:157 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00157 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota H, Okuno R, Hatakeyama K, Uchitani Y, Sadamasu K, Hirai A, et al. Molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolated from pediatric patients in Tokyo, Japan. Japanese journal of infectious diseases. 2015;68(1):76–8. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.336 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki Y, Seto J, Itagaki T, Aoki T, Abiko C, Matsuzaki Y. Gene Mutations Associated with Macrolide-resistance and p1 Gene Typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Isolated in Yamagata, Japan, between 2004 and 2013. Kansenshogaku zasshi The Journal of the Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases. 2015;89(1):16–22. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai Y, Miyashita N, Kubo M, Akaike H, Kato A, Nishizawa Y, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of macrolides, minocycline, and tosufloxacin against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57(5):2252–8. 10.1128/AAC.00048-13 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craven RB, Wenzel RP, Calhoun AM, Hendley JO, Hamory BH, Gwaltney JM Jr. Comparison of the sensitivity of two methods for isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1976;4(3):225–6. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjhie JH, van Kuppeveld FJ, Roosendaal R, Melchers WJ, Gordijn R, MacLaren DM, et al. Direct PCR enables detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in patients with respiratory tract infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1994;32(1):11–6. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cousin A, de Barbeyrac B, Charron A, Renaudin H, Bébéar C, editors. Analysis of RFLPs of amplified cytadhesin P1 gene for epidemiological study of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. 10th International Congress of the International Organization for Mycoplasmology (IOM); 1994; Bordeaux, France.

- 21.Sasaki T, Kenri T, Okazaki N, Iseki M, Yamashita R, Shintani M, et al. Epidemiological study of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in japan based on PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the P1 cytadhesin gene. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1996;34(2):447–9. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cousin-Allery A, Charron A, de Barbeyrac B, Fremy G, Skov Jensen J, Renaudin H, et al. Molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains by PCR-based methods and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Application to French and Danish isolates. Epidemiology and infection. 2000;124(1):103–11. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenri T, Taniguchi R, Sasaki Y, Okazaki N, Narita M, Izumikawa K, et al. Identification of a new variable sequence in the P1 cytadhesin gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae: evidence for the generation of antigenic variation by DNA recombination between repetitive sequences. Infection and immunity. 1999;67(9):4557–62. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spuesens EB, Oduber M, Hoogenboezem T, Sluijter M, Hartwig NG, van Rossum AM, et al. Sequence variations in RepMP2/3 and RepMP4 elements reveal intragenomic homologous DNA recombination events in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 7):2182–96. 10.1099/mic.0.028506-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenri T, Suzuki M, Horino A, Sekizuka T, Kuroda M, Fujii H, et al. Complete Genome Sequences of the p1 Gene Type 2b and 2c Strains Mycoplasma pneumoniae KCH-402 and KCH-405. Genome announcements. 2017;5(24). 10.1128/genomeA.00513-17 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz MH, Desai HP, Morrison SS, Benitez AJ, Wolff BJ, Caravas J, et al. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae genomes to investigate underlying population structure and type-specific determinants. PloS one. 2017;12(4):e0174701 10.1371/journal.pone.0174701 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balish MF, Santurri RT, Ricci AM, Lee KK, Krause DC. Localization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence-associated protein HMW2 by fusion with green fluorescent protein: implications for attachment organelle structure. Molecular microbiology. 2003;47(1):49–60. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause DC, Leith DK, Wilson RM, Baseman JB. Identification of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins associated with hemadsorption and virulence. Infection and immunity. 1982;35(3):809–17. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenri T, Okazaki N, Yamazaki T, Narita M, Izumikawa K, Matsuoka M, et al. Genotyping analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical strains in Japan between 1995 and 2005: type shift phenomenon of M. pneumoniae clinical strains. Journal of medical microbiology. 2008;57(Pt 4):469–75. 10.1099/jmm.0.47634-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki Y, Seto J, Shimotai Y, Itagaki T, Katsushima Y, Katsushima F, et al. Multiple-Locus Variable-Number Tandem-Repeat Analysis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Isolates between 2004 and 2014 in Yamagata, Japan: Change in Molecular Characteristics during an 11-year Period. Japanese journal of infectious diseases. 2017;70(6):642–6. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2017.276 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Oishi T, Miyata I, Wakabayashi S, Kono M, Ono S, et al. Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection, Japan, 2008–2015. Emerging infectious diseases. 2017;23(10):1703–6. 10.3201/eid2310.170106 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuoka M, Narita M, Okazaki N, Ohya H, Yamazaki T, Ouchi K, et al. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2004;48(12):4624–30. 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4624-4630.2004 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morozumi M, Hasegawa K, Kobayashi R, Inoue N, Iwata S, Kuroki H, et al. Emergence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae with a 23S rRNA gene mutation. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2005;49(6):2302–6. 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2302-2306.2005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumke R, Jacobs E. Antibody Response to Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Protection of Host and Influence on Outbreaks? Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:39 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00039 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan L, Li D, Zhang L, Hao C, Sun H, Shao X, et al. Pediatric clinical features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection are associated with bacterial P1 genotype. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2017;14(3):1892–8. 10.3892/etm.2017.4721 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun H, Xue G, Yan C, Li S, Zhao H, Feng Y, et al. Changes in Molecular Characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Clinical Specimens from Children in Beijing between 2003 and 2015. PloS one. 2017;12(1):e0170253 10.1371/journal.pone.0170253 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao F, Liu L, Tao X, He L, Meng F, Zhang J. Culture-Independent Detection and Genotyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Clinical Specimens from Beijing, China. PloS one. 2015;10(10):e0141702 10.1371/journal.pone.0141702 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JK, Lee JH, Lee H, Ahn YM, Eun BW, Cho EY, et al. Clonal Expansion of Macrolide-Resistant Sequence Type 3 Mycoplasma pneumoniae, South Korea. Emerging infectious diseases. 2018;24(8):1465–71. 10.3201/eid2408.180081 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho PL, Law PY, Chan BW, Wong CW, To KK, Chiu SS, et al. Emergence of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Hong Kong Is Linked to Increasing Macrolide Resistance in Multilocus Variable-Number Tandem-Repeat Analysis Type 4-5-7-2. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2015;53(11):3560–4. 10.1128/JCM.01983-15 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumke R, von Baum H, Luck PC, Jacobs E. Occurrence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains in Germany. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2010;16(6):613–6. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02968.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eshaghi A, Memari N, Tang P, Olsha R, Farrell DJ, Low DE, et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in humans, Ontario, Canada, 2010–2011. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19(9). 10.3201/eid1909.121466 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diaz MH, Benitez AJ, Winchell JM. Investigations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in the United States: trends in molecular typing and macrolide resistance from 2006 to 2013. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2015;53(1):124–30. 10.1128/JCM.02597-14 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diaz MH, Benitez AJ, Cross KE, Hicks LA, Kutty P, Bramley AM, et al. Molecular Detection and Characterization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae Among Patients Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia in the United States. Open forum infectious diseases. 2015;2(3):ofv106. 10.1093/ofid/ofv106 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishiguro N, Koseki N, Kaiho M, Ariga T, Kikuta H, Togashi T, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of azithromycin, clarithromycin, minocycline and tosufloxacin against macrolide-resistant and macrolide-sensitive Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0173635 10.1371/journal.pone.0173635 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spuesens EB, van de Kreeke N, Estevao S, Hoogenboezem T, Sluijter M, Hartwig NG, et al. Variation in a surface-exposed region of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae P40 protein as a consequence of homologous DNA recombination between RepMP5 elements. Microbiology. 2011;157(Pt 2):473–83. 10.1099/mic.0.045591-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sluijter M, Kaptein E, Spuesens EB, Hoogenboezem T, Hartwig NG, Van Rossum AM, et al. The Mycoplasma genitalium MG352-encoded protein is a Holliday junction resolvase that has a non-functional orthologue in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Molecular microbiology. 2010;77(5):1261–77. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07288.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnakumar R, Assad-Garcia N, Benders GA, Phan Q, Montague MG, Glass JI. Targeted chromosomal knockouts in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2010;76(15):5297–9. 10.1128/AEM.00024-10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li S, Liu F, Sun H, Zhu B, Lv N, Xue G. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Strain S355, Isolated in China. Genome announcements. 2016;4(2). 10.1128/genomeA.00087-16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwartz SB, Mitchell SL, Thurman KA, Wolff BJ, Winchell JM. Identification of P1 variants of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by use of high-resolution melt analysis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2009;47(12):4117–20. 10.1128/JCM.01696-09 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenri T, Ohya H, Horino A, Shibayama K. Identification of Mycoplasma pneumoniae type 2b variant strains in Japan. Journal of medical microbiology. 2012;61(Pt 11):1633–5. 10.1099/jmm.0.046441-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao J, Liu Y, Wang M, Jiang C, You X, Zhu C. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae P1 subtype variations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2014;78(1):24–8. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.08.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Schematic illustration of the p1 operon region and comparison of 11 p1 subtypes. Three light blue arrows indicate orf4 (MPN140), p1 (MPN141), and orf6 (MPN142) genes of the p1 operon. The approximate size of the operon is shown above in base pairs (bp). The positions correspond to P40 and P90 proteins are shown in the orf6 gene. Pink, green, and blue rectangles below the p1 and orf6 genes indicate approximate positions of RepMP repetitive sequence regions (RepMP4-c, RepMP2/3-d, and RepMP5-c). Black rectangles indicate approximate positions of sequence variations of p1 and orf6 genes using type 2 strain FH as reference. Probable origins of the variation of these sequences (suffixes of RepMPs are identical to the variations) are indicated next to gray rectangles (also see panel B). Representative strains that harbor genes of the corresponding subtype are indicated on the left. Accession numbers of the subtype sequences are shown on the right. Type 2b is also referred to as type 2V in other reports [26,49,50]. Sequence information of the orf6 gene of the type 2c2 strain P53 was kindly provided by Dr. Fei Zhao of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The orf6 sequence of the type 2e strain Mp100 has not yet been reported [51]. (B) Distribution of RepMP regions in M. pneumoniae genome. Approximate positions of 8 RepMP4, 12 RepMP2/3, and 8 RepMP5 regions in M. pneumoniae genome are indicated by colored boxes. Two RepMP2/3 regions (RepMP2/3-k and -l) were newly identified during genome sequencing analysis of KCH-402 and KCH-405 strains (GenBank accession nos. AP017318 and AP017319) [25]. Suffixes of RepMP regions (-a to -k) are based on the nomenclature system proposed by Spuesens et al. previously [24,45].

(TIF)

The light blue arrows indicate the p1 and orf6 genes. The p1 gene of strain M241 had a truncation at the C-terminus due to DNA recombination between the repetitive sequence regions RepMP2/3-d and RepMP2/3_e (also see S1B Fig). Small orange arrows indicate approximate positions of PCR primer binding sites (ADH1, ADH2, ADH3, ADH4, and 23e-R1). The lower right panel is an electrophoresis pattern in 0.8% agarose gel of DNA fragments obtained as PCR products from FH and M241 strain genomes by using ADH3 and 23e-R1 primers. The regions corresponding to the PCR products are indicated by red arrows. A faint 1.9 kb band in FH strain suggests a presence of similar recombination event in growth population of FH strain.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(PDF)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.