Abstract

Objective

Patients with extradural spine tumors are at an increased risk for intraoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and postoperative wound dehiscence due to radiotherapy and other comorbidities related to systemic cancer treatment. In this case series, we discuss our experience with the management of intraoperative durotomies and wound closure strategies for this complex surgical patient population.

Methods

We reviewed our recent single-center experience with spine surgery for primarily extradural tumors, with attention to intraoperative durotomy occurrence and postoperative wound-related complications.

Results

A total of 105 patients underwent tumor resection and spinal reconstruction with instrumented fusion for a multitude of pathologies. Twelve of the 105 patients (11.4%) reviewed had intraoperative durotomies. Of these, 3 underwent reoperation for a delayed complication, including 1 epidural hematoma, 1 retained drain, and 1 wound infection. Of the 93 uncomplicated index operations, there were a total of 9 reoperations: 2 for epidural hematoma, 3 for wound infection, 2 for wound dehiscence, and 2 for recurrent primary disease. One patient was readmitted for a delayed spinal fluid leak. The average length of stay for patients with and without intraoperative durotomy was 7.3 and 5.9 days, respectively, with a nonsignificant trend for an increased length of stay in the durotomy cases (p=0.098).

Conclusion

Surgery for extradural tumor resections can be complicated by CSF leaks due to the proximity of the tumor to the dura. When encountered, a variety of strategies may be employed to minimize subsequent morbidity.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid leak, Dura mater, Spinal neoplasms, Surgical wound infection

INTRODUCTION

Unintentional durotomy and postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak are well-known complications to the spine surgeon. In elective cases, the incidence of unintentional durotomy has been estimated at approximately 1.5%–10%, with a higher risk in revision surgeries and a lower risk in cervical cases [1-5]. When present, CSF leaks contribute to patient morbidity, often requiring positioning restrictions in the postoperative setting, as well as increase the risk for more serious complications such as wound dehiscence and central nervous system infection. The presence of CSF leaks also has been shown to increase the length of inpatient hospitalizations, intraoperative times, and total costs associated with surgery [6].

Spinal tumors, including both solid and liquid metastases and primary vertebral tumors, are often adherent to adjacent dura which increases the risk for iatrogenic durotomy during surgery. While metastatic lesions may involve veins that are adherent to thin dura, primary vertebral tumors require complex surgery that may raise the risk of iatrogenic CSF leak. Furthermore, many patients with tumors have received perioperative radiotherapy as well as multiple surgeries, increasing their risk of soft tissue-related complications including wound dehiscence and CSF leaks leading to CSF fistula or pseudomeningocele [5,7].

To date, though many excellent articles have been written about spinal pseudomeningoceles, incidental durotomies, and CSF leak management after routine spine surgery [1,2,8,9], there is still relatively little written that is specific to the spine tumor population. We present here on a single-center experience of surgery for extradural spine tumor resections and reconstruction, with a focus on the incidence of these complications and strategies for avoidance and management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed all patients who underwent resection of extradural lesions and spinal reconstruction by the senior author from August 2008 to May 2014. Basic demographics as well as details regarding tumor type and operative nuances were gleaned from chart review. We included only patients aged 18 years or older. We excluded any patient with primary intradural lesions, though we retained patients whose primarily epidural tumor had dural involvement or intradural invasion. We also excluded any patients who underwent biopsy without resection.

Data was collected on the type of tumor (solid metastatic disease, hematogenous origin, primary vertebral tumor, or other lesions), cell type of origin, presence of intraoperative CSF leak, postoperative management, postoperative complication rate, length of stay, and available follow-up length. Discrete variables were summarized by counts, percentages, and ranges, continuous variables by means. The subset of patients with evidence of intraoperative CSF leak was identified and compared to the cohort without CSF leak using a 2-sided Mann-Whitney U-test for length of stay and a chi-square test for difference in CSF leak rate by tumor type. A significance threshold was set at p<0.05 for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

We reviewed the data for 105 patients who fit our inclusion criteria. The average patient follow-up was 10.9 months (range, 0.5–36.5 months). Patients underwent tumor resection and spinal reconstruction for a multitude of pathologies (Table 1). Seventy-eight patients (74%) had solid tumor metastases, most commonly breast, lung, renal and prostate metastases, while there were 15 patients (14%) with hematogenous-based malignancies. Ten patients (9.5%) underwent surgical resection of primary vertebral tumors and 2 patients (2%) for other pathologies initially thought to be cancer. All patients received instrumented spinal fusion after resection. Twelve of the 105 surgeries (11.4%) were complicated by intraoperative durotomy and CSF leak of which 7 were in metastatic cancer, 2 in hematogenous cancer, and 3 in the primary vertebral tumor groups, with no statistically significant difference in CSF leak by tumor type (p=0.242). The cause and location of the leaks included epidural tumor resection around the nerve root in 7 cases, direct invasion of the dura in 3 cases and iatrogenic durotomy from surgery in 3 cases. Of these 12 patients, 2 had lumbar subarachnoid drains (LSADs) placed intraoperatively to help manage the CSF leak.

Table 1.

Recent experience with extradural tumor resection and spinal reconstruction

| Type of tumor & tumor pathology | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Metastases | |

| Lung | 19 |

| Renal | 12 |

| Breast | 25 |

| Prostate | 10 |

| Colon | 5 |

| Parotid | 1 |

| Salivary | 2 |

| Pancreatic | 2 |

| Thyroid | 2 |

| Total | 78 |

| Hematogenous-based | |

| Plasmacytoma | 10 |

| Lymphoma | 5 |

| Total | 15 |

| Primary vertebral tumors | |

| Sarcoma | 2 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 2 |

| Paraganglioma | 2 |

| Hemangioma | 2 |

| Chordoma | 2 |

| Total | 10 |

| Other | |

| Inflammatory lesion | 1 |

| Osteonecrosis after radiation | 1 |

| Total | 2 |

Of the 12 patients with intraoperative durotomy, 3 underwent reoperation for a delayed complication: 1 epidural hematoma, 1 retained drain, and 1 wound infection. Of the 93 uncomplicated index surgeries, there were a total of 9 reoperations: 2 epidural hematoma, 3 wound infections, 2 wound dehiscences, and 2 for recurrent primary disease (Table 2). One patient was readmitted for a delayed CSF leak necessitating placement of a LSAD. The average length of stay of patients who had an intraoperative durotomy was 7.3 days, whereas it was 5.9 days in those undergoing uncomplicated (no durotomy) surgery (p=0.098). All CSF leaks/durotomies identified in surgery were repaired primarily and a drain left in place postoperatively set to gravity drainage.

Table 2.

Summary of patients with intraoperative durotomy

| Patient No. | Age/sex | Tumor pathology | Location | Operation | CSF leak management | Subsequent complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69/F | Breast metastasis | T7–8 | T7–8 Corpectomy, T6–9 Laminectomies, and T5–10 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture and muscle tissue packing. | None |

| 2 | 63/F | Colon metastasis | T3 | T3 Corpectomy and T1–5 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture and albumin/glutaraldehyde glue | None |

| 3 | 48/M | Hemangioma | L1 | L1 Spondylectomy, T12 and L2 Laminecotmies, and T11–L3 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture. Lumbar drain placed intraoperatively | Reoperation for subsequent wound infection |

| 4 | 30/F | Hemangioma | T11 | T11 Laminectomy and Vertebroplasty, T10–12 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture, muscle packing, and albumin/glutaralde- hyde glue | None |

| 5 | 39/F | Paraganglioma | T5 | T5–6 Laminectomies, Partial T5 Corpectomy, T3–8 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture, muscle packing, and albumin/glutaralde- hyde glue | Readmission for positional head- aches and drainage of seroma |

| 6 | 56/F | Lung metastasis | T6 | T6 Corpectomy, T4–8 Instrumented Fusion | Onlay of an absorbable gelatin sponge and polyethylene glycol hydrogel | None |

| 7 | 51/F | Invasive lung (pancoast tumor) | C7–T2 | C7–T2 Laminectomies, C6–T3 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture | None |

| 8 | 54/M | Invasive lung (pancoast tumor) | T3–5 | T3–5 Corpectomies and Cage Placement, T1–8 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture | None |

| 9 | 78/F | Plasmacytoma | L3 | L3 Corpectomy, L3–5 Laminectomies, L2–5 Instrumented Fusion | Onlay of an absorbable gelatin sponge and polyethylene glycol hydrogel | None |

| 10 | 54/F | Plasmacytoma | T10 | T10 Corpectomy, T5–10 Laminecotmies, T4–12 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with suture | None |

| 11 | 47/F | Renal metastasis | T12–L3 | T12 Corpectomy, T12–L3 Laminectomies, T10–L5 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with polyethylene glycol hydrogel | Reoperation for hematoma |

| 12 | 56/M | Prostate metastasis | T11–12 | T11–12 Laminectomies, Partial T10 Corpectomy, T10–L1 Instrumented Fusion | Primary repair with muscle packing | None |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

We describe representative cases from this series to illustrate management and avoidance strategies for CSF leak and woundrelated complications.

1. Case 1 – Intra- and Perioperative Management in an Erosive Odontoid Lesion with Dural Invasion

This 46-year-old woman was referred to us after workup for several months of progressive left-sided neck pain radiating over the left occiput and ear, neck stiffness, and loss of neck range of motion. Physical examination revealed mild weakness in both arms. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a left epidural soft tissue mass at the levels of C1–2 with spinal cord compression and erosion into the dens (Fig. 1). Further imaging showed no evidence for cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases. She underwent suboccipital craniectomy for decompression and tumor resection, occiput-C4 fusion, and complex dural repair with an allogenic dural graft reinforced with a pedicled muscle flap from the paraspinous muscles (Fig. 2) and synthetic dural sealant. Pathological examination was consistent with sarcoma. The fascia and overlying muscle layer were closed with interrupted absorbable suture, and the skin was closed with a running vertical mattress nylon stitch. A LSAD was placed immediately postoperatively given her high risk for CSF leak. The LSAD remained in place for 3 days following surgery, with strict head of bed restrictions and minimization of direct pressure on the incision.

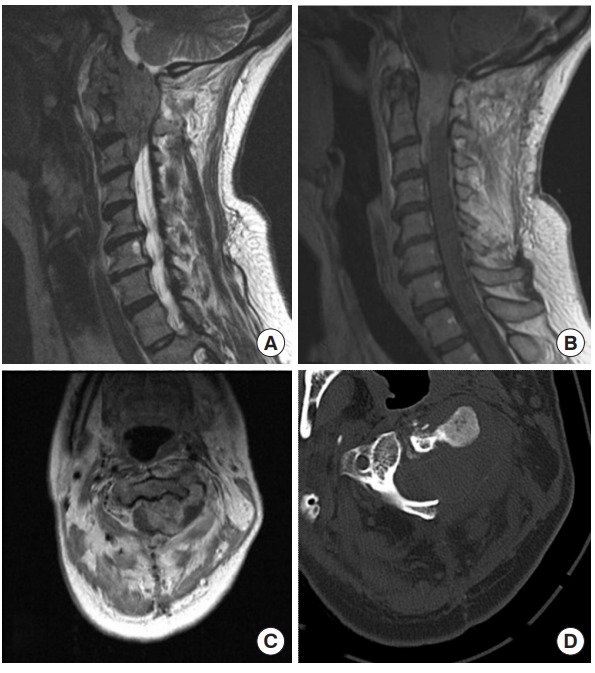

Fig. 1.

Preoperative images of case 1, a 46-year-old female who presented with cervical epidural sarcoma. (A) Sagittal T2, (B) sagittal gadolinium-enhanced T1, (C) axial gadolinium-enhanced T1 MRI, and (D) noncontrast axial computed tomography (CT) scan through the tumor at the level of C2. An enhancing epidural mass is seen extending from the foramen magnum down to the level of the C3 vertebra in the epidural space. The CT scan reveals significant bony erosion.

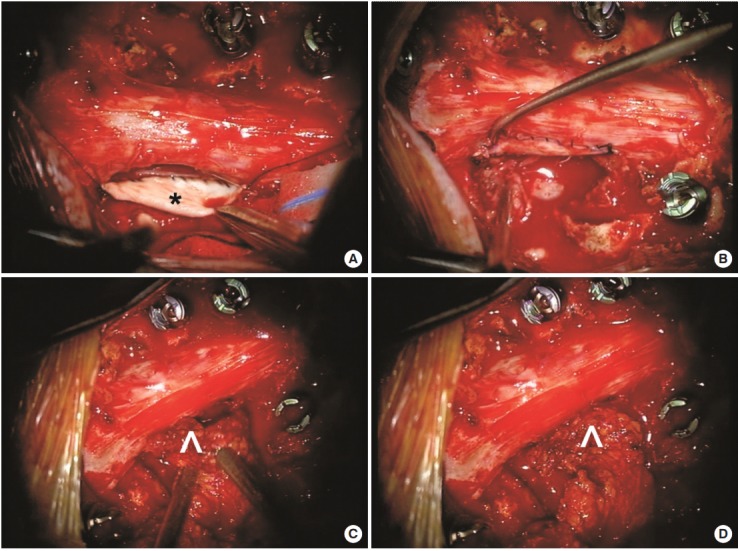

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative photographs from the tumor resection in case 1. Pathological analysis confirmed that the mass was a sarcoma. The tumor had invaded through the dura and complete excision necessitated some dural resection, creating a dural defect that could not be primarily repaired. (A) An allogenic dural graft (*) was sutured to the ventral edge of the dural defect. (B) The dural graft is sutured circumferentially to the defect. (C) Given the large area of the defect and the likelihood of a microscopic cerebrospinal fluid leak through the incision line, muscle (^) was mobilized from the paraspinal region as a pedicle flap and (D) this was sutured to the edge of the dural graft for reinforcement.

Three weeks later, she underwent radiotherapy for regrowth of the mass in the paraspinal muscles. Her preoperative weakness improved dramatically following surgery and radiotherapy. She experienced no neurological or wound-related complications following this treatment.

2. Case 2 – Technical Considerations in a Primary Vertebral Tumor Requiring En Bloc Sacrectomy and Nerve Root Ligation

This 52-year-old woman presented with progressive buttock and leg pain over 1–2 years. She reported groin and genital numbness and endorsed difficulty with bowel movements but denied urinary incontinence. Past surgical history was significant only for hysterectomy. On examination, her reflexes were normal bilaterally with no evidence of clonus. Strength was full in all major muscle groups and her gait was normal. MRI demonstrated a large diffuse sacral mass with presacral involvement and neural foraminal expansion (Fig. 3). The lesion appeared to reach the S1–2 disk space but did not extend above that level. Imageguided (IR) needle biopsy confirmed the lesion as a grade II chondrosarcoma.

Fig. 3.

Preoperative imaging of case 2, a 52-year-old woman with a large sacral mass. (A) Axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows invasion of the spinal canal at the level of the midsacrum. Coronal (B) and sagittal (C) T1 gadolinium-enhanced MRI. The cystic destructive and peripherally-enhancing lobular mass was suggestive of chondrosarcoma.

She was taken to the operating room for staged resection and complex reconstruction. Stage 1 consisted of an anterior transperitoneal sacral dissection and en bloc tumor excision. Stage 2 consisted of L5–S1 laminectomies with ligation of the thecal sac, en bloc sacrectomy, and L4-pelvis instrumented fusion (Fig. 4). The S1 nerve roots were cauterized and sacrificed as part of the oncologic resection. The thecal sac was clipped just distal to the sacral root takeoffs and ligated with 0-silk ties. This ligation end was then oversewn with end-to-end running 5-0 nonabsorbable suture. The thecal sac was cut with tenotomy scissors and the suture line reinforced with dural sealant. No occult CSF leak at the thecal stump or rostrally was observed with an intraoperative Valsalva maneuver. The complex gluteal wound was closed with a large pedicle omental flap with the assistance of our plastic surgery colleagues.

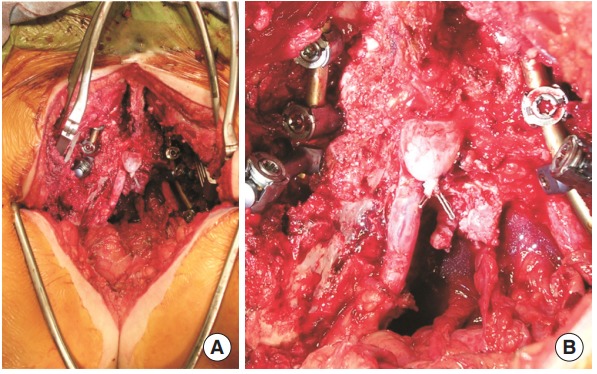

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative photographs from the sacrectomy and tumor resection for case 2. Pathology was consistent with chondrosarcoma. (A) A partial sacrectomy was performed for full resection of the tumor. The incision extended down into the gluteal crease. (B) Higher magnification photograph shows the ligated thecal sac.

One month later, she developed persistent fever and wound breakdown requiring surgical debridement and placement of a vacuum-assisted wound closure device. She never developed meningitis or CSF leak. Her neurological status has remained stable postoperatively.

3. Case 3 – Key Points in Performing a Repeat Resection with Postradiation Dural Adhesions

This 39-year-old woman with history of a thoracic paraganglioma, resected 10 years prior requiring T5 corpectomy and fusion, developed radiographic recurrence on routine followup (Fig. 5A, B). She was neurologically intact on presentation, but serum catecholamines were elevated. She underwent revision decompression and tumor resection at T5–6 with a transpedicular approach followed by replacement of the original instrumentation. Due to extensive epidural scarring, 3 small durotomies were found and repaired primarily. These primary repairs were then reinforced with a pedicle muscle flap and synthetic dural sealant. No further intraoperative CSF leaks were noted. Two subfascial Jackson-Pratt drains were placed and left to gravity. Fascia was closed with running nonabsorbable suture, subcutaneous tissue with running absorbable and skin with running vertical mattress nylon suture.

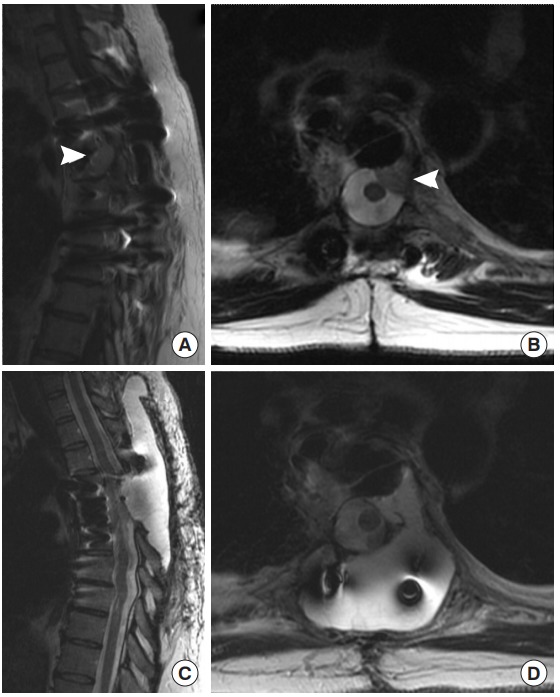

Fig. 5.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images from case 3, a 39-year-old female with a recurrent, extradural paraganglioma. The patient had a previous resection with thoracic spine stabilization years prior. (A) Sagittal T1 gadolinium-enhanced and (B) axial T2 MRI prior to her second surgery show recurrence of the extradural paraganglioma (arrowheads), abutting the dura. During her surgery for repeat resection, three small durotomies were encountered and repaired primarily and reinforced with muscle. Despite these precautions, she developed a pseudomeningocele postoperatively. T2 sagittal (C) and axial (D) images showed the T2 bright cerebrospinal fluid filling a pseudomeningocele above the resection site and spreading through the paraspinal musculature. She was treated conservatively with percutaneous drainage of the collection.

Postoperatively, CSF gradually appeared in the drain bulbs. An LSAD was placed and the subfascial drains were clamped. After 3 days there was no further evidence for CSF leakage, and the drains were removed. On 1-month follow-up, she returned with postural headaches. MRI revealed a large pseudomeningocele (Fig. 5C, D). She was managed conservatively with image-guided percutaneous needle drainage with good clinical resolution.

DISCUSSION

Iatrogenic durotomy during spine surgery is a well-recognized complication that can lead to morbidity in the postoperative period. A recent meta-analysis of patients who underwent surgery for degenerative spine disease or scoliosis reported an incidental durotomy rate of 1.6% [5]. However, no similar studies have been conducted in patients with spinal tumors, and observation suggests that this rate would be higher in the oncologic population due to the adherent nature of tumors to the dura [7]. While small dural rents may not violate the arachnoid and no appreciable CSF leak occurs intraoperatively, there is a risk for leakage once the patient changes position postoperatively and gravity increases their intrathecal pressure. This can lead to a pseudomeningocele or CSF fistulae [9], wound breakdown and meningitis [10]. In rare cases, unrecognized durotomies have been reported to result in intracranial hemorrhage [11,12]. While many durotomies may heal spontaneously, certain factors such as previous irradiation, poor nutrition, steroid use and elevated CSF pressures may decrease this spontaneous healing rate [9]. These predisposing factors can be common in patients with metastatic spinal tumors and also in some with primary vertebral tumors. Therefore, any possible violation of the dura (either by the tumor or iatrogenically) must be addressed immediately and repaired intraoperatively to minimize the risk of a postoperative complication. Furthermore, patients with spinal tumors are at high risk for wound-related complications due to the complex and extensive nature of their surgery [7,13,14]. We report our series of patients in whom this complication occurred and describe the strategies that we employ to fix the durotomy in the operating room.

We report an 11.4% incidence of intraoperative CSF leak during surgery for extradural spinal tumors, with the rates being 9% in patients with solid metastases, 13% in patients with hematologic metastases, and 30% in primary vertebral tumor resections. Many case series focusing on surgery for spinal tumors do not report the rate of intraoperative durotomy and only report the rate of pseudomeningocele or CSF fistula formation which should only theoretically occur after unrecognized or improperly repaired durotomies. Chaichana et al. [15] reviewed their single-institution experience with metastatic tumors causing spinal cord compression in 114 patients and noted a 10% wound dehiscence rate and a 3% postoperative CSF leak rate requiring reoperation. Arrigo et al. [16] reviewed a cohort of 200 patients with metastatic tumors to the spine and reported a 0.5% postoperative CSF leak rate and 3.5% wound dehiscence rate within 30 days of surgery. Ghogawala et al. [17] analyzed the postoperative complications of 85 patients with metastatic spinal disease and found a statistically significant higher rate of major wound complication in patients who had been previously irradiated relative to those who underwent surgery de novo (32% vs. 12%). Primary vertebral tumors may pose an even higher risk of iatrogenic durotomy and postoperative wound breakdown given the complexity of surgery. In a small series of patients undergoing radical resection of sacral chordomas and chondrosarcomas, 9 of 20 patients (45%) developed postoperative wound complications [18]. It has been well described that those with sacral tumors are at a uniquely high risk for wound-related surgical complications [19,20] given the location of the incision and its proximity to urine and feces. Although, few reports discuss their rate of intraoperative CSF leak and detailed closure techniques, we believe that attention to specific techniques in durotomy repair and wound closure may lead to a lower complication rate in this at-risk population.

Based on our experience, we have distilled our most important strategies in managing CSF leaks in patients with spinal tumors in Table 3. Primary closure with the use of adequate visualization (microscope) of the dura is the most important single strategy. All other factors will likely fail if this is not accomplished well in surgery. Muscle/fascia autograft or allogeneic dural grafts should be used if primary closure cannot be achieved due to the size of the defect. LSADs can be used when encountering a durotomy to equalize CSF pressure in the intradural and extradural spaces to allow for healing of the durotomy [9]. Patients with these drains must be monitored carefully as spinal headaches, nausea, vomiting, infections and meningitis may develop with their usage [21-23]. Refractory CSF leaks ultimately may require permanent CSF diversion with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or lumboperitoneal shunt [24]. Bed and head-of-bed positioning should be maximized to keep lumbar thecal pressure and wound pressure low. A recent multicenter, prospective randomized controlled study with one agent revealed a significantly higher rate of watertight closure with use of the synthetic dural sealant relative to using suture alone (100% vs. 64%) in patients undergoing spine surgery requiring durotomy [25]. The study found no significant differences in postoperative complications including infection, wound healing or delayed CSF leak, however there is considerable interest in developing similar compounds to reinforce dural repairs and grafts in both cranial and spine surgery.

Table 3.

Summary of strategies for durotomy repair and wound closure in patients undergoing resection of extradural tumors

| Summary of strategy | |

|---|---|

| Durotomy repair and management | 1. Use of operating microscope |

| 2. Valsalva to search for occult cerebrospinal fluid leak | |

| 3. Running 4-0 or 5-0 thread for primary dural closure | |

| 4. Allogenic or autologous dural graft | |

| 5. Free or pedicle muscle flap sutured to incision line or graft | |

| 6. Adjuvant synthetic dural sealant (optional) | |

| 7. Lumbar subarachnoid drain | |

| Wound closure | 1. Avoidance of crosslinks |

| 2. Eliminate potential space | |

| 3. Subfascial closed drains without suction | |

| 4. Paraspinal or complex muscle flaps | |

| 5. Watertight closure of fascia with interrupted or running suture | |

| 6. Postoperative vitamin supplementation | |

| Postoperative management | 1. Flat head of bed for 24–48 hours |

| 2. Logroll precautions to keep pressure off incision |

Regarding spinal hardware, implants should be as low profile as possible and crosslinks, though helpful in providing structural integrity, should be avoided overlying the dura as it prevents adjacent muscle from filling the dead space after resection (Fig. 6). Also, adequate paraspinal muscle coverage is an important tool to prevent further CSF leakage. We often enlist the assistance of our plastic surgery department mobilize muscle flaps to cover the resection defect, to help with soft tissue coverage [13,26-28]. In cases where patients require reoperation for a wound infection and surrounding muscle is of poor quality, many surgeons use a vacuum-assisted wound closure device [29,30]. However, extreme caution must be exercised in these patients as any occult CSF leak could be exacerbated by direct suction from the vacuum. The use of postoperative subfascial drains has been a topic of some controversy after recognized durotomy during spinal surgery. Two studies report no statistically significant difference in the incidence of postoperative epidural hematomas after spine surgery with or without postoperative subfascial drains [31,32], however we regularly use subfascial drains to gravity drainage for 2–3 days to prevent pseudomeningocele formation which can fistulize through the fascia and skin. Finally, many patients in this tumor population, especially those with metastatic disease, may suffer from malnutrition which can adversely affect wound healing [33-35]. We advocate the use of postoperative vitamin supplementation for 10–14 days in all patients following metastatic spine tumor resection with the following oral regimen: Vitamin A 10,000 IU daily, Vitamin C 5,000 IU twice daily, Zinc 220 mg daily and a multivitamin tablet daily. Healthy and expeditious wound healing is essential as many of these patients may receive radiation, which can adversely affect the wound, within days to weeks of the surgery [7,36].

Fig. 6.

Sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of a patient with a pseudomeningocele after attempted repair of a durotomy during surgery. The imaging artifact from the crosslink between the 2 fusion rods is visible extending through the middle of the pseudomeningocele. This patient underwent a wound revision and removal of this crosslink. The dural defect was identified and repaired again, with a muscle flap, and the paraspinal muscles were reapproximated over the defect. Postoperative sagittal (C) and axial (D) T2 MRI shows no reaccumulation of the cerebrospinal fluid collection and the musculature was allowed to rest directly on top of the dural repair, contributing to the tamponade effect.

CONCLUSION

With data that supports surgical intervention in certain patients with metastatic spinal tumors, and with surgical advances allowing for more complex spinal reconstructions, CSF leaks and wound dehiscence continue to pose therapeutic dilemmas in the postoperative recovery period. We report our experience with intraoperative CSF leaks in a series of patients with spinal tumors and extradural involvement and suggest strategies to address these issues.

Footnotes

John H. Chi is a consultant for K2M and Medtronic. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.McMahon P, Dididze M, Levi AD. Incidental durotomy after spinal surgery: a prospective study in an academic institution. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:30–6. doi: 10.3171/2012.3.SPINE11939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi Y, Sato T, Hyodo H, et al. Incidental durotomy during lumbar spine surgery: risk factors and anatomic locations: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18:165–9. doi: 10.3171/2012.10.SPINE12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker GA, Cizik AM, Bransford RJ, et al. Risk factors for unintended durotomy during spine surgery: a multivariate analysis. Spine J. 2012;12:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MH, Rihn J, Steele G, et al. Postoperative management protocol for incidental dural tears during degenerative lumbar spine surgery: a review of 3,183 consecutive degenerative lumbar cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2609–13. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000241066.55849.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams BJ, Sansur CA, Smith JS, et al. Incidence of unintended durotomy in spine surgery based on 108,478 cases. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:117–23. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181fcf14e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber C, Piek J, Gunawan D. Health care costs of incidental durotomies and postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks after elective spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:2065–8. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilsky MH, Fraser JF. Complication avoidance in vertebral column spine tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2006;17:317–29, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammisa FP, Jr, Girardi FP, Sangani PK, et al. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2663–7. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couture D, Branch CL., Jr Spinal pseudomeningoceles and cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deFreitas DJ, McCabe JP. Acinetobacter baumanii meningitis: a rare complication of incidental durotomy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:115–6. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu CH, Ho ST, Kong SS, et al. Intracranial subdural hematoma after unintended durotomy during spine surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:100–2. doi: 10.1007/BF03020428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karaeminogullari O, Atalay B, Sahin O, et al. Remote cerebellar hemorrhage after a spinal surgery complicated by dural tear: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(1 Suppl):E215. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000163688.17385.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang DW, Friel MT, Youssef AA. Reconstructive strategies in soft tissue reconstruction after resection of spinal neoplasms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1101–6. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261555.72265.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen MA, Mayfield J, Lauryssen C, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection in spinal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(2 Suppl):149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaichana KL, Pendleton C, Sciubba DM, et al. Outcome following decompressive surgery for different histological types of metastatic tumors causing epidural spinal cord compression. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:56–63. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.SPINE08657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrigo RT, Kalanithi P, Cheng I, et al. Charlson score is a robust predictor of 30-day complications following spinal metastasis surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:E1274–80. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318206cda3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghogawala Z, Mansfield FL, Borges LF. Spinal radiation before surgical decompression adversely affects outcomes of surgery for symptomatic metastatic spinal cord compression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:818–24. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh PC, Xu R, Sciubba DM, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes following en bloc resections for sacral chordomas and chondrosarcomas: a series of twenty consecutive patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2233–9. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b61b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen KW, Yang HL, Lu J, et al. Risk factors for postoperative wound infections of sacral chordoma after surgical excision. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24:230–4. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181ea478a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sciubba DM, Nelson C, Gok B, et al. Evaluation of factors associated with postoperative infection following sacral tumor resection. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:593–9. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro SA, Scully T. Closed continuous drainage of cerebrospinal fluid via a lumbar subarachnoid catheter for treatment or prevention of cranial/spinal cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:241–5. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199202000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Açikbaş SC, Akyüz M, Kazan S, et al. Complications of closed continuous lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:475–80. doi: 10.1007/s007010200068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitchel SH, Eismont FJ, Green BA. Closed subarachnoid drainage for management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after an operation on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:984–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannallah D, Lee J, Khan M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1101–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KD, Wright NM. Polyethylene glycol hydrogel spinal sealant (DuraSeal Spinal Sealant) as an adjunct to sutured dural repair in the spine: results of a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1906–12. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fdb4db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Disa JJ, Smith AW, Bilsky MH. Management of radiated reoperative wounds of the cervicothoracic spine: the role of the trapezius turnover flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:394–7. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mericli AF, Tarola NA, Moore JH, Jr, et al. Paraspinous muscle flap reconstruction of complex midline back wounds: risk factors and postreconstruction complications. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65:219–24. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c47ef4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garvey PB, Rhines LD, Dong W, et al. Immediate soft-tissue reconstruction for complex defects of the spine following surgery for spinal neoplasms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1460–6. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d5125e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones GA, Butler J, Lieberman I, et al. Negative-pressure wound therapy in the treatment of complex postoperative spinal wound infections: complications and lessons learned using vacuum-assisted closure. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:407–11. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.5.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehbod AA, Ogilvie JW, Pinto MR, et al. Postoperative deep wound infections in adults after spinal fusion: management with vacuum-assisted wound closure. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:14–7. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000133493.32503.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awad JN, Kebaish KM, Donigan J, et al. Analysis of the risk factors for the development of post-operative spinal epidural haematoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1248–52. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.16518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payne DH, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, et al. Efficacy of closed wound suction drainage after single-level lumbar laminectomy. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:401–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds KD, Franklin FA, Leviton LC, et al. Methods, results, and lessons learned from process evaluation of the high 5 school-based nutrition intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:177–86. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todorovic V. Food and wounds: nutritional factors in wound formation and healing. Br J Community Nurs. 2000;43-4:46. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2002.7.sup2.12981. 48 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson B. Nutrition and wound healing: the necessity of assessment. Br J Nurs. 2005;14:S30. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.Sup5.19955. S32, S34 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itshayek E, Yamada J, Bilsky M, et al. Timing of surgery and radiotherapy in the management of metastatic spine disease: a systematic review. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:533–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]