Abstract

Background:

Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM) rarely receive gonorrhea/chlamydia testing. The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate a pay-it-forward strategy to increase gonorrhea/chlamydia testing among MSM. Pay-it-forward has one person receive a gift, then asks the same person if they would like to give a gift to another person.

Methods:

We used a quasi-experimental pragmatic study to compare a pay-it-forward model to standard of care at two HIV testing sites for MSM. A pay-it-forward program was implemented for three months, during which men were offered free gonorrhea/chlamydia testing and given the option of donating money toward testing for future participants. Both sites then switched to standard of care for three months, offering dual testing at the standard price. We compared test uptake and financial costs in the two groups.

Findings:

408 men were included in this study. 203 men were offered pay-it-forward, and 205 were offered standard of care. Overall, 109 (109/203, 53·7%) men received gonorrhea/chlamydia testing in the pay-it-forward group and 12 (12/205, 5·9%) men received gonorrhea/chlamydia testing in the standard of care group (adjusted odds ratio 19·73, 95%CI 10·02–38·85). This was a first gonorrhea or chlamydia test for 86% (104/121) of men. 89% (97/109) of men in the pay-it-forward group donated some amount. The incremental unit cost per test in the pay-it-forward group was 67 USD, compared to 503 USD in the standard of care group.

Interpretation:

Pay-it-forward may be a sustainable model for expanding integrated HIV testing services among MSM in China.

Introduction

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are common STDs which spread rapidly and silently through communities of men who have sex with men (MSM). The prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydia among Chinese MSM is as high as 10–20%.1,2 These two STDs are known to increase the risk of HIV acquisition3 and transmission,4 but are often asymptomatic at extragenital sites.5 WHO guidelines recommend regular gonorrhea and chlamydia testing for MSM.6 US Centers for Disease Control guidelines recommend testing at least once a year for all MSM, and more frequently for men with higher sexual risk.7

However, few MSM in China receive gonorrhea and chlamydia testing. Previous studies suggest that less than half of MSM have ever received a gonorrhea or chlamydia test.8,9 This major missed public health opportunity is likely related to poor government support for testing programs,10 unlinked systems for HIV testing and other STDs,11,12 and insufficient community ownership. First, China has no screening guidelines for gonorrhea or chlamydia testing among MSM. There are also no widespread programs supporting gonorrhea and chlamydia testing.10 Second, the extensive HIV testing system in China is not integrated to facilitate other STD testing.11,12 Third, many advances in the HIV field have been catalyzed by input from MSM and civil society.13 China has relatively low MSM community ownership of health services, partly due to the persistent stigma.14 Existing community-based services and promotional campaigns are focused on HIV, with fewer services related to gonorrhea or chlamydia testing.15

In response to this need, several community organizations organized a gonorrhea and chlamydia testing pilot program using a pay-it-forward model. Pay-it-forward has one person receive a gift, then asks the same person if they would like to give a gift to another person (Video).16,17 Pay-it-forward fits within the broader field of behavioral economics which uses multiple disciplines to understand human decision making. Pay-it-forward chains of giving are sometimes driven by unconnected generous individuals,18 but more often organized by a group with a common purpose.19,20 Studies have shown that pay-it-forward can be sustainable and promote generosity.21

In this study, a pay-it-forward model was applied to paying for dual gonorrhea/chlamydia testing at two free HIV/syphilis testing sites for MSM. Program organizers contributed an initial pool of funding, and MSM at these sites were offered a free gonorrhea/chlamydia test with the option to contribute toward testing for future participants. The purpose of this quasi-experimental study is to evaluate a pay-it-forward intervention on gonorrhea and chlamydia testing among Chinese MSM.

Methods

Setting

The study was undertaken in Guangzhou, China at two sites – an STD clinic for MSM and a local MSM community-based organization (CBO). The STD clinic site was embedded in an outpatient clinic; the CBO site operated within a CBO office in the community. These two sites were chosen because they were developed with strong input from MSM and provided free HIV/syphilis testing to all MSM. Both sites were staffed by MSM volunteers, nurses, and public health staff. There were no clinical doctors at either site. Blood draws, testing, results reporting, and follow-up of HIV and syphilis tests were handled by staff at each site. Both sites followed the same study procedures (Appendix, page 2).

Study design

This study was designed as a quasi-experimental pragmatic trial at the two sites. We chose a pragmatic design in order to evaluate this program in a real-life context to benefit MSM in Guangzhou. A quasi-experimental study involves evaluating an intervention without the use of randomization.22 In this study, we evaluated the pay-it-forward intervention model against a standard of care control (Fig 1). The pay-it-forward program was implemented December 2017 to February 2018 and the standard of care was implemented March 2018 to May 2018.

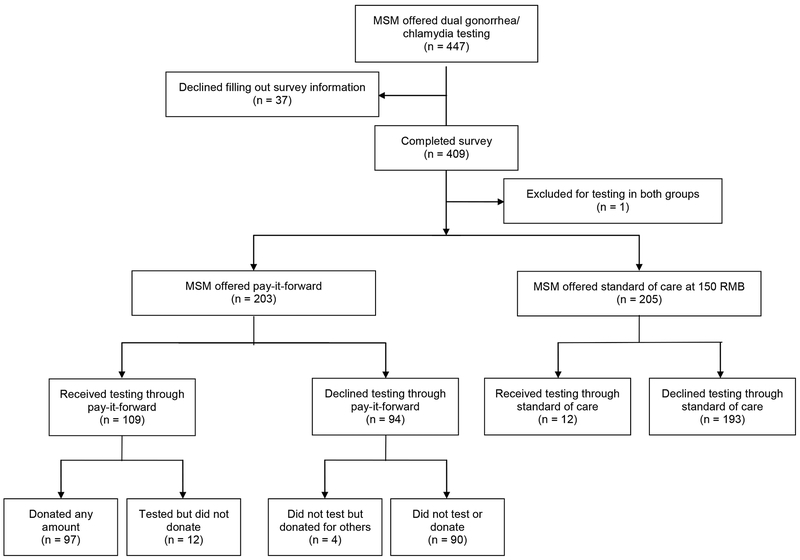

Fig 1: Study flow chart.

The study used a quasi-experimental design. The intervention took place from December 2017 to February 2018, and the standard of care control took place from March 2018 to May 2018.

Pay-it-forward program

The pay-it-forward intervention was developed through crowdsourcing in three ways: (1) an open challenge contest23 was used to develop the name and style of the program materials; (2) at the CBO site, hand-written notes from previous participants in the program encouraged testing for future participants; (3) community volunteers helped organize the program. At both of the program sites, MSM who were waiting for HIV and syphilis testing were offered dual gonorrhea/chlamydia testing (Appendix, page 2). First, men were provided a brief (5 minute) introduction to gonorrhea and chlamydia testing using a pamphlet (Appendix, page 3). Program organizers then explained the pay-it-forward program, including the purpose (to promote gonorrhea/chlamydia testing), the opportunity to receive free gonorrhea and chlamydia tests, and the voluntary decisions to test and to contribute money (Appendix, page 4). Men were told that the patient price of gonorrhea and chlamydia testing was 150 RMB ($24 USD), but previous men attending the clinic had donated money to cover this cost. Thus, each man could receive a free gonorrhea and chlamydia test, then decide whether to donate money (pay-it-forward) for future men to receive the same option. Men were assured that donating was completely optional and advised to pay any amount that was feasible for them. Each man’s gonorrhea and chlamydia test fees were covered by a combination of the initial funding pool from the program organizers and the donations from previous participants. At the CBO site, men were also shown a postcard with a message written by a previous pay-it-forward contributor and told that they could also write a postcard message for a future participant (Appendix, page 4). Men then decided whether or not to receive combined gonorrhea/chlamydia testing. All men were asked to fill out a brief survey about their sexual history, testing history, and attitudes toward the testing program, regardless of whether or not they tested.

MSM who received testing were asked about sexual practices (oral, anal receptive, anal insertive) and advised to receive pharyngeal, anal, or urethral testing. All participants were informed that their information would be kept confidential, and results would be sent to them in one week. Men who agreed to participate either had a nurse collect the sample (STD clinic site) or self-collected the sample (CBO site).24 At the STD clinic site, samples were immediately delivered to the laboratory. Self-collected samples from the CBO site were stored at room temperature overnight, then transported to the Southern Medical University Dermatology Hospital for laboratory testing. Program organizers informed participants of their test results via WeChat, a popular messaging application with monetary transfer functionality. Men with positive test results were counseled and directed to the WeChat page of Southern Medical University Dermatology Hospital where they could make an appointment to receive treatment and follow-up. Counseling included information about condom use, safe sexual practices, and the importance of testing.

Standard of care

During the standard of care period, men were offered gonorrhea and chlamydia testing at the standard patient price. All men were provided a brief introduction about gonorrhea and chlamydia testing using the same pamphlet, but did not receive the explanation about pay-it-forward or view the associated postcards (Appendix, page 2).

Laboratory testing

All urine and anal swab samples were analyzed at Southern Medical University Dermatology Hospital using Cobas 4800 CT/NG DNA detection kits (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). At the STD clinic site, HIV testing was performed using the Diagnostic Kit for Antibody to HIV ½ (Abon Pharmaceuticals, Northvale, New Jersey, USA) and syphilis testing was performed using the Treponema Pallidum Antibodies Rapid Test (Abon Pharmaceuticals, Northvale, New Jersey, USA). At the CBO site, HIV testing was performed using the Third Generation Diagnostic Kit for Antibody to HIV rapid test (InTec, Xiamen, China) and syphilis testing was performed using the Syphilis Antibody (anti-Treponema Pallidum) rapid test (InTec, Xiamen, China).

Data collection

We extracted data from all MSM who were approached regarding gonorrhea/chlamydia testing. Program organizers compared the collected WeChat social media IDs of the men in order to identify men who tested more than once; these men were excluded from the analysis. The primary outcome for this study was uptake of dual gonorrhea/chlamydia testing. This was defined based on laboratory receipt of a sample and return of results to the man. For each participant in the pay-it-forward arm, we recorded the amount that they contributed to the next participant.

The survey instrument collected data on sociodemographic characteristics, including age, education, marital status, income; data on sexual behavior including previous sex with men, role in anal sex (primarily insertive, primarily receptive, or about half and half), condomless anal sex in the past three months, and number of sex partners in the past three months; previous HIV testing, gonorrhea testing, and chlamydia testing. For both groups, we collected information on reasons for accepting or declining gonorrhea and chlamydia testing (Appendix, page 5). Among men who received testing in the pay-it-forward group, the most commonly cited reason was the pay-it-forward program (49/102, 48%). For the pay-it-forward group, we also asked about perceived benefits and barriers of the pay-it-forward program (Appendix, page 6).

We collected HIV and syphilis test results for all participants, as well as gonorrhea and chlamydia test results for those tested.

Data analysis

Our main hypothesis was that the pay-it-forward program would increase dual gonorrhea/chlamydia test uptake compared to the standard of care. This hypothesis was pre-specified during study design. We used descriptive statistics to examine demographic and behavioral characteristics of MSM. We compared the gonorrhea/chlamydia testing rate between the pay-it-forward model and the standard of care model using chi-squared test and logistic regression, reported as crude odds ratios (cOR) and adjusted odds ratios (aOR), by adjusting for nationality, marital status, income, and site of testing. We chose these covariates because they are potential confounders. We also calculated incremental unit costs per gonorrhea/chlamydia test and per gonorrhea/chlamydia diagnosis. We first calculated the total financial cost for each group, then divided these costs by the number of men tested and by the number of men diagnosed in each group. All data were analyzed using SAS version 9·4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics and Role of the Funding Source

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

From December 2017 to May 2018, we approached a total of 447 participants across the two clinics. One man who received testing through both groups was excluded from our analysis. 408 were included in the analysis, 161 from the STD clinic and 247 from the CBO site. We analyzed data from 203 men who were offered pay-it-forward testing and 205 who were offered the standard of care (Fig 1).

Participant characteristics

Demographic characteristics were similar between the pay-it-forward group and the standard of care group (Table 1). The majority of participants were aged 30 or younger (75%), of Han ethnicity (95%), had a bachelor’s degree or above (67%), and had never married (90%), and had a monthly income of USD $1582 (10,000 RMB) or below (81%). 65% reported ever disclosing their sexual orientation to family, friends, or healthcare professionals. 37% of participants reported condomless anal sex within the past three months, and 5% reported a female partner in the past three months. 76% had previously tested for HIV, while 16% had previously tested for gonorrhea and 11% had previously tested for chlamydia.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics by experimental condition. Shown as n (%).

| Pay-it-forward (n = 203) |

Standard of Care (n = 205) | P-value# | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0·69 | ||

| 30 or under | 153 (75%) | 158 (77%) | |

| over 30 | 50 (25%) | 47 (23%) | |

| Nationality | 0·79 | ||

| Han Chinese | 194 (96%) | 197 (96%) | |

| Other | 9 (4%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Marital Status | 0·08 | ||

| Never married | 177 (88%) | 191 (93%) | |

| Ever married | 24 (12%) | 14 (7%) | |

| Education | 0·89 | ||

| Below Bachelor’s | 66 (33%) | 68 (33%) | |

| Bachelor’s and above | 137 (67%) | 137 (67%) | |

| Monthly income (USD) | 0·80 | ||

| $0–157·27 | 24 (12%) | 27 (13%) | |

| $157·28–786·36 | 64 (32%) | 58 (29%) | |

| $786·37–1572·72 | 77 (39%) | 78 (39%) | |

| > $1572·72 | 34 (17%) | 39 (19%) | |

| Disclosure as MSM | 0·10 | ||

| Never | 77 (38%) | 62 (30%) | |

| Ever | 126 (62%) | 143 (70%) | |

| Average No. male partners in last 3 months* | 1·90±2·02 | 1·70±1·57 | 0·27 |

| Female partner in last 3 months | 0·49 | ||

| No | 191 (94%) | 196 (96%) | |

| Yes | 12 (6%) | 9 (4%) | |

| Position w/ male partner | 1·00 | ||

| Primarily insertive | 59 (31%) | 62 (31%) | |

| About half and half | 64 (33%) | 68 (34%) | |

| Primarily receptive | 68 (36%) | 72 (35%) | |

| Condomless anal sex in past 3 months | 0·57 | ||

| No | 130 (65%) | 127 (62%) | |

| Yes | 71 (35%) | 78 (38%) | |

| Previously tested for HIV | 0·27 | ||

| No | 54 (27%) | 45 (22%) | |

| Yes | 149 (73%) | 160 (78%) | |

| Previously tested for gonorrhea or chlamydia | 0·86 | ||

| No | 168 (83%) | 171 (83%) | |

| Yes | 35 (17%) | 34 (17%) |

Shown as mean ± standard deviation.

Chi-squared test.

Gonorrhea/chlamydia testing uptake and test results

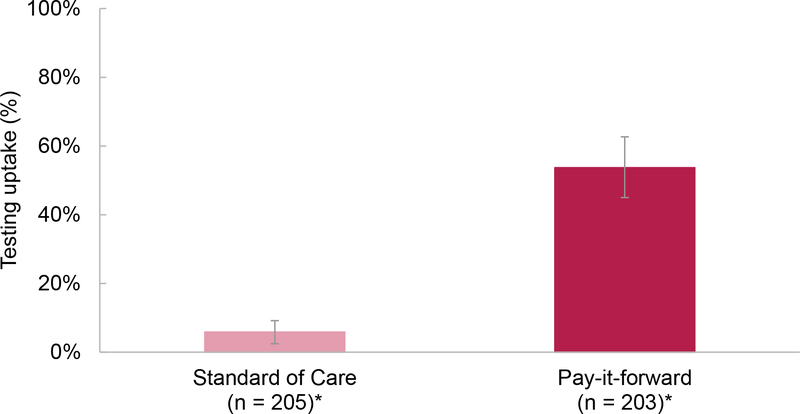

Fig 2 shows the gonorrhea/chlamydia test uptake in the pay-it-forward versus standard of care groups. Overall, 109 (109/203, 53·7%) men received gonorrhea/chlamydia testing in the pay-it-forward group and 12 (12/205, 5·9%) men received gonorrhea/chlamydia testing in the standard of care group (adjusted OR=19·73, 95%CI 10·02–38·85). Testing uptake rates were similar at the STD clinic and CBO sites. Multivariable regression models adjusting for marital status, education, income, and study site showed that the odds of receiving a gonorrhea/chlamydia test were significantly higher in the pay-it-forward group compared to the standard of care (aOR = 19·73, 95% CI 10·02–38·85, p< 0·0001, Table 2).

Fig 2: Gonorrhea/chlamydia testing uptake in the intervention versus standard of care groups, n = 408.

Multivariable regression adjusted for age, nationality, marital status, education, income, and site of test showed aOR = 19·73, 95% CI 10·02–38·85, P < 0·0001.

Table 2:

Proportion of people tested for CT/NG in the control and intervention groups among MSM in Guangzhou, China (N=408)

| N | MSM who received gonorrhoea/chlamydia testing (%) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard of care | 205 | 12 (5·9%) | Ref | Ref |

| Pay-it-forward | 203 | 109 (53·9%) | 18·65 (9·78, 35·54) | 19·74 (10·03, 38·85)* |

| 18·43 (9·48, 35·84)€ | ||||

| 19·73 (10·02, 38·85)£ |

Note:

Model adjusted for age, nationality, marital status, income and site of testing;

model adjusted for age, nationality, marital status and site of testing;

model adjusted for nationality, marital status, income and site of testing.

This was a first gonorrhea test for 97/121 men (80%) and a first chlamydia test for 104/121 men (86%). Five men (4%) were diagnosed with gonorrhea and 15 (12%) were diagnosed with chlamydia. 16/408 men (4%) were diagnosed with HIV and 4/408 (1%) with syphilis.

Attitudes toward testing and pay-it-forward

Within the pay-it-forward group, 49/102 (49%) participants reported that their primary reason for getting tested was the pay-it-forward program (Appendix, page 5). In both groups, the most common reasons for not testing were “I don’t need to get tested” and “I don’t know about gonorrhea and chlamydia” (Appendix, page 5). The most commonly cited benefits of the pay-it-forward program were awareness of one’s own health status, increasing testing among the MSM community, and reciprocal giving (Appendix, page 6).

Pay-it-forward contributions

Of the 109 MSM who received testing through pay-it-forward, 97 (89%) chose to contribute some amount. The average donation per participant was 64·84 RMB ± 56·92 ($10 USD). The largest donation was 200 RMB ($32 USD) and the median donation was 50 RMB ($8 USD) (Appendix, page 7). Additionally, four men who did not receive gonorrhea/chlamydia testing contributed a total of 470 RMB ($75 USD).

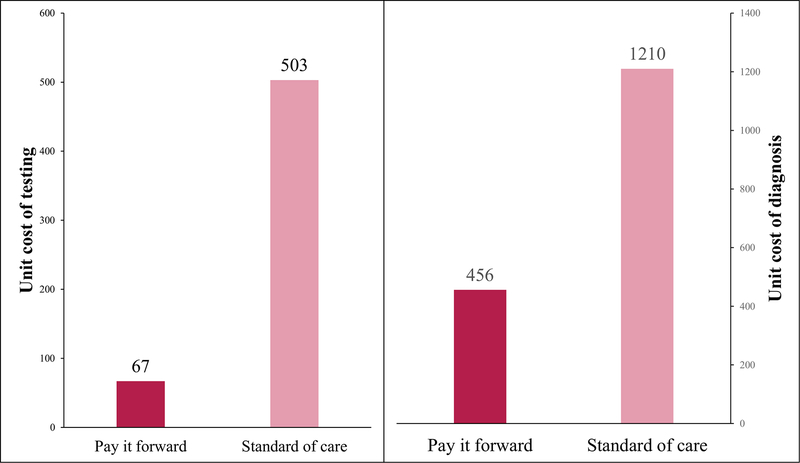

Costing analysis

The incremental unit cost per gonorrhea/chlamydia test in the pay-it-forward group was 67 USD, compared to 503 USD in the standard of care group (87% reduction). The incremental cost per newly diagnosed gonorrhea or chlamydia infection was 456 USD in the pay-it-forward group and 1210 USD in the standard of care group (70% reduction) (Fig 3).

Fig 3:

Incremental unit cost per gonorrhea/chlamydia test (left) and gonorrhea/chlamydia diagnosis (right).

Discussion

Low STD testing rates represent a major missed public health opportunity among MSM in China. We evaluated a pay-it-forward STD testing model and found that the model substantially increased test uptake compared to the standard of care. From a financial perspective, most of the costs associated with testing were supported by local MSM, suggesting a viable pathway to sustainable service delivery.

Our data shows that pay-it-forward can increase gonorrhea/chlamydia testing uptake. 54% of participants in the pay-it-forward group received gonorrhea/chlamydia testing, and about half of participants reported that the main reason for testing was the pay-it-forward program. We were unable to find literature demonstrating that pay-it-forward increases service uptake. Pay-it-forward programs are usually presented to individuals who have already committed to purchasing the services. Increased STD testing may be related to reduced testing fees, increased community engagement, or contagious kindness. Men participating in the pay-it-forward program did not have to pay for gonorrhea/chlamydia testing and the small fee associated with testing may be a barrier to testing. Second, the pay-it-forward spurred community engagement by actively engaging MSM in the development and implementation of the service. Previous studies have shown that community engagement in sexual health is associated with increased HIV testing among MSM.25 Finally, by participating in the program, pay-it-forward participants receive not only the test, but also the benefit of feeling cared for by others and the opportunity to help others.26 Most men in the pay-it-forward group reported that getting other MSM to test or helping someone else were benefits of pay-it-forward. This is consistent with research showing that generous behavior can spread through communities.27

The pay-it-forward program reached a subset of high-risk, untested MSM. Among all MSM who tested, this was the first gonorrhea or chlamydia test for 80% and 86%, respectively. Overall, we identified 5 cases (4%) of gonorrhea and 15 cases (12%) of chlamydia. This is consistent with prevalence rates from a previous study of MSM in Guangzhou.2 Previous studies have evaluated and recommended combined HIV and syphilis testing.11,28 Our study extends this literature by demonstrating a feasible approach for integrating gonorrhea/chlamydia testing with HIV testing.

Among testers in the pay-it-forward group, 89% (98/109) chose to donate to future men. The average donation was $10 USD. This is notable and suggests that MSM are willing to invest in their healthcare despite accessing free HIV and syphilis testing services. In our program, we initially invested enough funding for 81 tests. 31 additional tests were covered entirely by contributions from previous testers, and at the end of the program period, there remained funding for 19 more tests. Compared to free testing, a pay-it-forward model can increase the number of available tests by distributing part of the cost to test recipients without making cost a barrier to access.29 From an implementation perspective, a pay-it-forward model that combines institutional funding with patient contributions could allow a limited amount of funding to go a longer way.30 Future programmatic efforts can investigate ways to make a pay-it-forward gonorrhea/chlamydia testing program independent and self-sustaining.

Our study has implications for research and implementation. The concept of pay-it-forward has often been used as a promotional tool,19–21 but its application to public health is novel. Future research should analyze the cost-effectiveness of pay-it-forward, as well as evaluate pay-it-forward in a randomized controlled trial over a longer duration of time. Qualitative research on understanding the motivations and optimal implementation may also be helpful. Our preliminary findings suggest that a pay-it-forward model may be an effective tool in promoting screening and has potential in creating a self-sustaining service. We did not find differences between test uptake rates at the two sites despite some differences in implementation, suggesting that pay-it-forward programs may be feasible across multiple settings. In low and middle-income countries, there is limited funding for many screening and preventive health services.30 Pay-it-forward may be a useful tool in promoting and funding these essential services.

Several important limitations merit discussion. First, this study is limited by its quasi-experimental design which prevents us from making direct inferences about causality. There may have been other unmeasured differences between the two groups. However, the two groups of men were similar in terms of socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics. Second, the pay-it-forward program was only piloted at two sites in Guangzhou aimed at HIV/syphilis testing for MSM. This limited our analysis to MSM who were already connected with community-based organizations willing to receive an HIV test. Third, the pay-it-forward intervention included both free testing and creating a sense of moral obligation to contribute to the health of other gay men. Our study could not differentiate to what extent these two factors individually contributed to the success of the program. Finally, the success of the program may vary depending on how embedded they are in a trusted MSM service. Although both sites showed similar rates of gonorrhea/chlamydia testing, both sites are trusted by the Guangzhou MSM community. It is not known whether such a program would be successful in other settings or among other populations, and further research is needed.

Conclusion

We evaluated a pay-it-forward model applied to preventive health services. We found high uptake of gonorrhea and chlamydia testing through the pay-it-forward program compared to the standard of care, suggesting that it is a useful tool for increasing testing uptake among MSM. In our study, the majority of testers were first-time testers of gonorrhea and chlamydia, and the program identified a substantial number of positive cases. Our results suggest that pay-it-forward may be a useful strategy for promoting public health services, leveraging contagious kindness to spur health.

Supplementary Material

Video Legend

Video summary of pay-it-forward.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In China, gonorrhea and chlamydia are common among MSM, but there have been few interventions to promote testing. We performed a PubMed search for “gonorrhea” or “chlamydia” with the terms “MSM,” “China,” and “testing” or “screening” or “intervention.” There were no date restrictions and the search was performed 15 June 2018. We identified two English language studies reporting rates of lifetime gonorrhea and chlamydia testing less than 50% among Chinese MSM. We also found one protocol for a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of automated text message reminders on STD testing. We did not find other studies on interventions for gonorrhea or chlamydia testing among MSM in China. We also searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms “pay it forward” or “generalized reciprocity.” We found several studies examining the behavioral economics of pay-it-forward pricing schemes, but did not identify any studies investigating pay-it-forward as a promotional strategy or applying generalized reciprocity to public health.

Added value of this study

This study evaluated a pay-it-forward model for gonorrhea and chlamydia testing among Chinese MSM. We found that a pay-it-forward model substantially increased test uptake compared to the standard of care. The program reached many untested MSM and identified new positive cases. This expands the literature by formally evaluating a pay-it-forward program focused on improving health.

Implications of all available evidence

Our study identified a high percentage of previously untested MSM and a large burden of disease, highlighting the low test uptake and the need for improved gonorrhea and chlamydia testing for Chinese MSM. A pay-it-forward testing program may be a promising strategy for creating a sustainable program for integrated HIV/STD testing among key populations.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health (NIAID R01AI114310), the Southern Medical University Dermatology Hospital, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation funded the study. We would also like to thank Weizan Zhu and Yang Zhang for their help with program coordination, Yang Zhao and Thomas Fitzpatrick for their help with program execution, and Yaohua Xue, Wujian Ke, and Liyan Yuan from SMU Dermatology Hospital for sample processing. Thanks to Kevin Cao for creating the video explaining pay-it-forward. We would like to thank Nicholas Christakis and the Yale Institute of Network Sciences for providing comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge all participants of the pay-it-forward program.

Funding: National Institutes of Health, Southern Medical University Dermatology Hospital, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

JDT and WT are on the advisory board for SESH Global, which was involved in organizing the study. All other authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Chen X-S, Peeling RW, Yin Y-P, Mabey DC. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in China: implications for control and future perspectives. BMC Med 2011; 9(1): 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Zhang X, Chen Z, et al. O17.1 Prevalence of neisseria gonorrhoeae and chlamydia trachomatis infections in different anatomic sites among men who have sex with men: results of 380 msm who attended a std clinic in guangzhou, china. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(Suppl 2): A38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53(4): 537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet 1997; 349(9069): 1868–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detels R, Green AM, Klausner JD, et al. The Incidence and Correlates of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infections in Selected Populations in Five Countries. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38(6): 503–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender people. 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/msm_guidelines2011/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm.

- 8.Lin L, Nehl EJ, Tran A, He N, Zheng T, Wong FY. Sexually transmitted infection testing practices among ‘money boys’ and general men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China: objective versus self-reported status. Sex Health 2014; 11(1): 94–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis A, Best J, Luo J, et al. Risk behaviours, HIV/STI testing and HIV/STI prevalence between men who have sex with men and men who have sex with both men and women in China. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27(10): 840–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng N, Guo Y, Padmadas S, Wang B, Wu Z. The increase of sexually transmitted infections calls for simultaneous preventive intervention for more effectively containing HIV epidemics in China. BJOG 2014; 121(s5): 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker JD, Yang L-G, Yang B, et al. A Twin Response to Twin Epidemics: Integrated HIV/Syphilis Testing at STI clinics in South China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 57(5): e106–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong JJ, Fu H, Pan S, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV and syphilis testing among men who have sex with men in China: a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45: 382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trapence G, Collins C, Avrett S, et al. From personal survival to public health: community leadership by men who have sex with men in the response to HIV. Lancet 2012; 380(9839): 400–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neilands TB, Steward WT, Choi KH. Assessment of stigma towards homosexuality in China: a study of men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2008; 37(5): 838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng W, Cai Y, Tang W, et al. Providing HIV-related services in China for men who have sex with men. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94(3): 222–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang Y-S, Takahashi N. Network Homophily and the Evolution of the Pay-It-Forward Reciprocity. PloS One 2011; 6(12): e29188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyde CR. Pay It Forward. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy K Ma’am, Your Burger Has Been Paid For. The New York Times. 2013. October 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cueva M Thanks, au lait: 750 pay it forward at Starbucks location. CNNcom. 2014. August 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wegert T JetBlue Pays It Forward Through a Social Storytelling Campaign With No End in Sight. The Content Strategist. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung MH, Nelson LD, Gneezy A, Gneezy U. Paying more when paying for others. J Pers Soc Psychol 2014; 107(3): 414–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker JD, Fenton KA. Innovation challenge contests to enhance HIV responses. Lancet HIV 2018; 5(3): e113–e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yared N, Horvath K, Fashanu O, Zhao R, Baker J, Kulasingam S. Optimizing screening for sexually transmitted infections in en using self-collected swabs - a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang TP, Liu C, Han L, et al. Community engagement in sexual health and uptake of HIV testing and syphilis testing among MSM in China: a cross-sectional online survey. J Int AIDS Soc 2017; 20(1): 21372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gneezy A, Gneezy U, Nelson LD, Brown A. Shared Social Responsibility: A Field Experiment in Pay-What-You-Want Pricing and Charitable Giving. Science 2010; 329(5989): 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010; 107(12): 5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker JD, Walensky RP, Yang L-G, et al. Expanding Provider-Initiated HIV Testing at STI Clinics in China. AIDS Care 2012; 24(10): 1316–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sepehri A, Chernomas R. Are user charges efficiency ‐ and equity‐enhancing? A critical review of economic literature with particular reference to experience from developing countries. Journal of International Development 2001; 13(2): 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard LM. Public and private donor financing for health in developing countries. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1991; 5(2): 221–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video Legend

Video summary of pay-it-forward.