Abstract

Background:

Emergency Department (ED) visits for migraine are burdensome to patients and to the larger healthcare system and society. Thus, it is important to determine strategies used to prevent ED visits and the common communication patterns between headache specialists and the ED team.

Objective:

We sought to understand 1. Whether headache specialists use headache management protocols. 2. The strategies they use to try and reduce the number of ED visits for headache. 3. Whether protocols are used in the EDs with which they are affiliated. 4. The level of satisfaction with the coordination of care between headache physicians and the ED.

Methods:

We surveyed via SurveyMonkey members of the American Headache Society Emergency Department/Refractory/Inpatient (EDRI) Section to understand their practice regarding patients who call their office to be seen urgently, and to understand their communication with their local EDs.

Results:

There were 96 eligible AHS members 50 of whom responded to questionnaires either by e-mail or in-person (52%). Of these, 59% of respondents reported giving rescue treatment to their patients to manage acute attacks. 54% reported using standard protocols for outpatients not responding to usual acute treatments. In the event of a request for urgent care, 12% of specialists reported bringing patients into the office most or all of the time, and 20% reported sending patients to the ED some or most of the time for headache management. Thirty six percent reported prescribing a new medicine and 30% reported providing telephone counseling some/most/all of the time. Sixty percent reported that their ED has a protocol for migraine management. Overall, 38% were usually or very satisfied with the headache care in the ED.

Conclusions:

A substantial number of headache specialists are dissatisfied with the care their patients receive in the ED. More standardized protocols for ED visits by patients with known headache disorders, and clear guidelines for communication between ED providers and treating physicians, along with better methods for follow-up following discharge from the ED might appear to improve this issue.

Keywords: emergency medicine, protocol, migraine, healthcare utilization, headache, health communication

Introduction

Migraine is a chronic condition characterized by disabling acute attacks. When urgent treatment needs arise, people with migraine who seek care from a headache specialist may call the headache specialist, make urgent visits to the headache center or go directly to the ED with or without notifying their practitioner. However, the ED is a suboptimal place for treatment because of the high charges, the long waits for treatment in a bright, noisy environment, and because ED care for migraine is often suboptimal. 1 Only about 20% of patients who go the ED for a migraine are pain free when they are discharged and in less than 24 hours, 64% of patients report that their migraines returned. 1 In addition, migraine patients in the ED may receive unnecessary tests (i.e. CT scans) and inappropriate first-line treatment including opioids. 2,3 Despite American Headache Society (AHS) guidelines stating that opioids should not be used as first line treatment for migraine in the ED, 4 opioids are used to treat migraine in more than 50% of ED visits. A recent study showed that the patients who received a non-opioid treatment (single-dose prochlorperazine) achieved sustained headache relief at double the rate compared to those who received single-dose hydromorphone, 3 the opioid used in 25% of ED visits for migraine. 5 Moreover, hydromorphone was associated with longer ED stays and additional medications to treat headache and related symptoms. 3

Many headache medicine clinicians aspire to keep their patients out of the ED, by providing management tools including using stratified care approaches and rescue therapies for use at home. 6,7 When ED visits are necessary, goals include optimizing the patient experience including speed of relief, minimizing cost and burden and facilitating coordination of ED care and follow-up care. Understanding current patterns of managing urgent headache problems in subspecialty care and ED treatment is a prelude to designing interventions to optimize acute headache problems when they arise.

In order to determine practice patterns in highly motivated physicians, we surveyed American Headache Society Members who were part of the Emergency Department/Refractory/Inpatient Section of the American Headache Society (AHS). In this group of specialists with a special interest in both headache and ED management, we sought to better understand 1. Whether headache specialists use headache management protocols. 2. The strategies they use to prevent the ED visits for headache. 3. Whether protocols are used in the EDs with which they are affiliated. 4. The communication they have with the ED regarding their patients with headache who present to the ED.

Methods

A survey was drafted by authors MTM, RBL and RC and distributed to members of the AHS Emergency Department/Refractory/Inpatient (EDRI) Section of the American Headache Society. (For the purposes of this paper, members of this group will be called “headache specialists” given that they are dues paying members of the American Headache Society, a requirement to be part of the EDRI Section.) The final survey incorporated edits from the Section and was distributed via SurveyMonkey to all EDRI members. Table 1 lists key survey questions. Of note, the survey was not limited to “migraine” treatments but rather “headache” treatments. By asking participants mainly about “headache” treatments, we intended to be more pragmatic since headache in the ED is most commonly diagnosed as Headache NOS-not migraine. 8 Also, initial acute treatment is defined as the patient’s go to or first line drug. Rescue medications are defined as medications used if the first line fails or if in the patient’s judgement there is a very low probability that the first line treatment will work. Preventive treatment is defined as a treatment that is taken prior to the onset of a headache and is intended to prevent a headache. Typically, it is given on a regular basis e.g. in the form of a daily oral medication. A standardized protocol was a protocol outlining possible steps to take in headache management. For several questions, the specialists inputted their own values for what percentage of their patients they offer particular treatments. The survey was available online for 30 days between May 2017 and June 2017 and on iPads and laptops at the EDRI Section meeting at the annual AHS Scientific meeting on June 10, 2017. IRB approval was not sought since there was no patient involvement or personal health information involved in the study.

Table 1:

Key survey questions in the Survey distributed to the EDRI section of the AHS:

| 1. For approximately what percentage of your headache patients do you provide each of the following? (Answer from 0–100%) |

| Acute Treatment |

| Preventive Treatment |

| Rescue Treatment (when Acute Treatment Fails) |

| Instructions for ED or Urgent Care treatment |

| Instructions for Infusion Center treatment |

| 2. Do you have standardized protocols for patients presenting or calling in with ongoing or severe headaches that are not responding to normal abortive treatments? |

| Yes/No |

| If yes, how often do you use them? (Answer in % of the time.) |

| 3. When a patient contacts you regarding a headache that is not responding, approximately how often do you do each of the following? (Answer choices: Never, Occasionally, Some of the time, Most of the time, Almost all or all the time) |

| Bring patient into office within 24 hours |

| Send patient to ED or Urgent Care |

| Send patient to Infusion Center |

| Prescribe a new medication |

| Provide phone counseling only |

| 4. Does your ED have a protocol for migraine management in the ED? |

| Yes/No |

| 5. When your patient goes to the ED, what is the usual procedure? |

| Patient has a written plan on your letterhead to bring to the ED |

| You call the ED with a history and a suggested plan |

| If you do not call the ED, the ED contacts your office before treatment |

| ED notifies your office of the visit post discharge |

| Patient is instructed to notify your office of the visit |

| ED uses its discretion regarding follow-up |

| 6. On average, how often are you notified that one of your patients has been seen in the ED or Urgent Care? |

| 7. Overall, how satisfied are you with ED management of your headache patients? (5 point Likert scale) |

Statistical Analyses

The analysis plan involved descriptive analyses only. Descriptive analyses were conducted using Excel.

Results

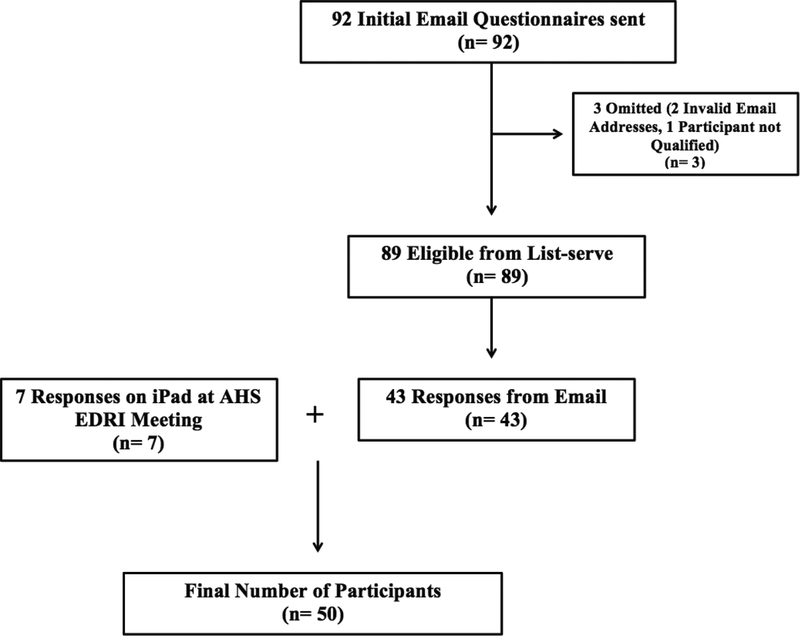

Eligible participants were section members included on the list serve with valid e-mail addresses and participants who attended the EDRI Section meeting who were not on the list serve. Of the 92 people on the Section list serve, 89 were eligible. In addition, there were seven Section attendees not on the list-serve who were eligible for a total of 96 eligible participants. By email, valid data was obtained on 43 of 89 email participants. There were seven participants at the Section meeting who were not on the list serve who completed the survey. (All eligible participants at the Section meeting completed the survey.) Thus, the aggregate participation rate in the survey was 52% (50/96). Of note, the responses of the three Headache Specialists who are authors of this manuscript were included in the 50 respondents.

Survey Demographics

Forty (n=40, 80%) of the participants identified as being at an academic institution, and 10 (n=10, 20%) participants identified as being part of a private practice.

Reported Management of Patients

Table 2 summarizes data on how often headache specialists report offering particular treatment options for their patients. For example, 65% of specialists offer acute treatment to 100% of their patients while only 23% of specialists offer rescue medication to 100% of their patients. We summed the percentages for offering a treatment more than 50% of the time (51–90%, 91–99% and 100%) for each treatment. Just over three quarters (77.5%) of providers offer acute treatment nearly all or all (91%−100%) of the time. Ninety percent of providers offer preventive treatment at least half of the time. Forty six percent of respondents reported giving rescue treatment to their patients to manage acute attacks in at least 50% of their patients. The majority of the providers (n=39, 80%) do not provide instructions for ED or Urgent Care treatment. About 90% (n=42, 89%) of providers provide instructions for infusion center treatment for less than 35% of their patients.

Table 2. –

Percentage of Headache Specialists Providing Each Treatment to Specified Percentages of their patients

| Treatments | 0–35 %(n) | 36–50 %(n) | 51–90 %(n) | 91–100 %(n) | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Treatment | 8.2 (4) | 2.0 (1) | 12.3 (6) | 77.5 (38)) | 49 |

| Preventative Treatment | 0 (0) | 10.4 (5) | 68.8 (33) | 20.8 (10) | 48 |

| Rescue Treatment | 25.0 (12) | 29.2 (14) | 20.8 (10) | 25.0 (12) | 48 |

| Instructions for ED or Urgent Care Treatment | 69.4 (34) | 10.2 (5) | 8.2 (4) | 12.3 (5) | 49 |

| Instructions for Infusion Center Treatment | 89.4 (42) | 0 (0) | 6.4 (3) | 0 (0) | 47 |

Table 3 shows what providers do when they are contacted by patients with ongoing headaches. Few (n=11, 22%) providers bring patients into the office most or all of the time. Two fifths of providers (n=20, 40%) report sending patients to the ED some or most of the time for headache management.

Table 3. –

Methods of Action for Non-Responsive Patient Headaches

| Method of Action | Never % (n) | Occasionally % (n) | Some of the Time % (n) | Most of the Time % (n) | Almost All or All of the Time % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bring Patient into the Office within 24 Hours | 6 (3) | 30 (15) | 42 (21) | 12 (6) | 10 (5) |

| Send Patient to ED or Urgent Care | 6 (3) | 52 (26) | 30 (15) | 10 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Send Patient to Infusion Center | 24 (12) | 36 (18) | 28 (14) | 10 (5) | 2 (1) |

| Prescribe a New Medication | 4 (2) | 24 (12) | 44 (22) | 24 (12) | 4 (2) |

| Provide Phone Counseling Only | 4 (2) | 36 (18) | 32 (16) | 20 (10) | 8 (4) |

Standardized Protocols

Fifty-four percent (n=22, 54%) of participants reported having standardized protocols in their office for patients presenting or calling in with on-going or severe headaches that are not responding to normal acute treatments. Of those who used standardized protocols, participants estimated that they use them 62.6% of the time.

Of the participants that responded, eight did not respond with a numerical value. Sixty percent (n=30, 60%) of participants responded that their ED has a protocol for migraine management in the ED. The other specialists (n=20, 40%) responded that their ED does not have a protocol for migraine management in the ED.

ED or Urgent Care Notification

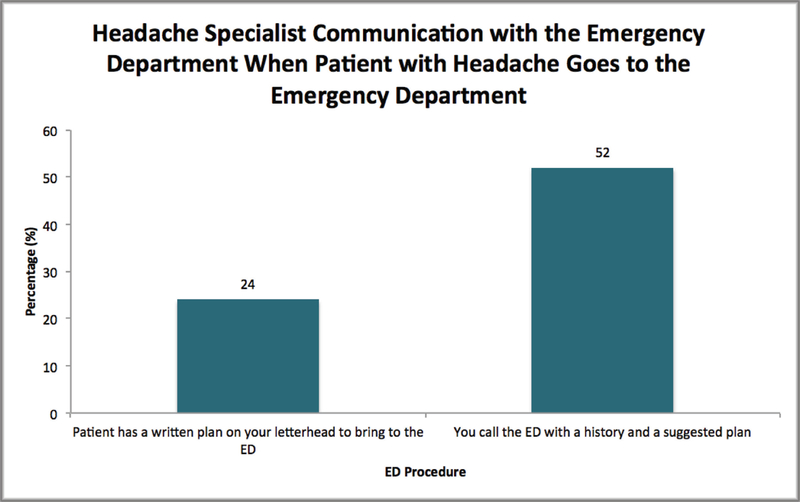

Figure 2 shows some of the efforts providers make to coordinate care before a patient presents to the ED. The majority of providers (n=26, 52%) call ahead to the ED. The figure also indicates headache specialists’ report of the discharge plans for migraine patients in the ED.

Figure 2. –

Headache Specialist Communication with the Emergency Department

Satisfaction with ED Management of Headache Patients

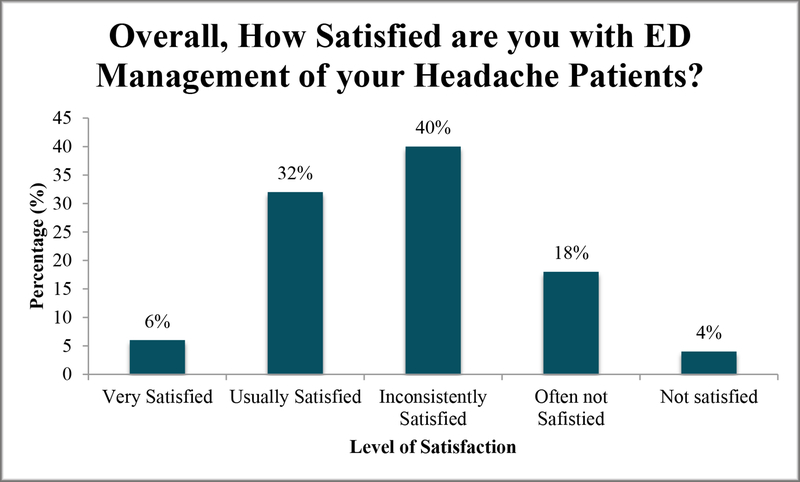

The majority of participants expressed dissatisfaction with ED management of headache patients, with 4% (2) of participants reporting not satisfied, 18% (9) of participants reporting often not satisfied, and 40% (20) of participants reporting inconsistently satisfied. Only 32% (16) of participants reported being usually satisfied, and 6% (3) of participants reported being very satisfied (Figure 3).

Figure 3. –

Satisfaction with ED Management of Headache Patients

Discussion

Our study sought to gain a better understanding of how providers with a special interest in ED/refractory headache approach and view the care of their patients when they require emergent or urgent care for a headache. Our findings indicate that many headache specialists do not provide a home treatment program for refractory headaches and do not prepare for future ED visits in their interactions with patients or ED clinicians. As such, we have several key findings: 1. There may be opportunities to reduce the need for ED visits for migraine. 2. There may be issues related to what happens when an urgent care situation arises. 3. An ED treatment plan is only used by one-fourth (n=12, 24%) of headache specialists.

There may be opportunities to reduce the need for ED visits for migraine. First, most providers (91.8%) give acute medications to most patients. Some providers feel that in people with frequent headache acute treatment does more harm than good by creating a risk for rebound and that the emphasis should be on prevention and behavioral pain management. Second, more than one fifth (22.5%) of providers report not giving acute treatments to all or nearly all of the patients. Perhaps this is because some patients do not respond to or have contraindications to acute treatment. For example, they have had a myocardial infarction and an ulcer so both triptans and NSAIDs are contraindicated, over the counter medications do not work, and they do not want to take or the providers do not want to give opioids. Third, most headache specialists do not report prescribing rescue medication, a major potential strategy for preventing ED visits. 9–11 These medications can be given if the typical migraine acute medication does not work; migraine rescue medications provide relief at home, so the patient does not have to go to the emergency room. Rescue medications such as promethazine have been proven effective in reducing headache pain as an emergency treatment 10 and can be given rectally when patients cannot tolerate oral medication. Anti-emetics may also be rescue medications, as they may help prevent dehydration and the need to go to the ED for rehydration. In addition, DHE nasal spray may be offered in certain patients as an attempt to avoid the need for DHE infusions. Rescue medications can be combined as well. Headache specialists report giving rescue treatment to 59% of their patients. Thus, despite their potential benefits, a substantial minority of headache specialists do not give rescue medications to their patients.

Only one fifth (n=10, 20.41%) of headache specialists discuss ED and urgent care to more than 50% of their patients, indicating that there might be barriers to communication early on. There may be issues related to what happens when an urgent care situation arises. Headache providers do not frequently have their patients come to the office for an appointment within 24 hours of a call. Only (n=6, 12%) of participants stated they bring their patient in most of the time, and only (n=5, 10%) stated they bring their patients in almost all or all of the time. This may explain why, according to one study, the majority of headache patients in the ED were there due to the inability to schedule an appointment as soon as they wanted. 1 Thus, there is likely a group of patients who want expedited medical care even though they might recognize their headache is not an emergency. CDC data indicates that approximately 80% of ED visits are due to the wish for expedited care, compared with 66% of visits which are for emergency care. 12

Protocols are not used the majority of the time in either the outpatient or the ED setting. Only about half (n=27, 54%) of headache specialists stated that they have standardized protocols for patients whose headaches are not responding to normal acute treatments. Rather, they are used only about 62% of the time. Two fifths (n=20, 40%) of headache specialists stated that their ED does not have protocol for migraine management in the ED. There are known benefits from the use of protocols in the ED. For example, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) support and endorse the use of standardized nursing protocol orders. These include standardized procedures, order sets, and standing orders, for use in the initial patient evaluation even prior to the evaluation by a physician or advanced practice provider. Such protocols have been found to be safe and effective in improving patient care. Moreover, they can help improve coordination of care and reinforce evidence-based care. 13

Given that close to two thirds (62%) were inconsistently/often not/or not satisfied with ED management of their headache patients, there may be room for improvement in headache patients’ care. To reduce the high number of headache patients in the ED, education and intervention methods can be taught to patients, as well as step-wise elaboration of medications and treatment plans, when initial therapy does not work. Better education and communication with respect to the ED is also essential to improved ED treatment of headache patients. Table 4 outlines some of these concepts.

Table 4:

Optimizing Migraine Care

| 1. Discuss rescue medication, a major strategy for preventing ED visits. |

| 2. Discuss issues related to what happens when an urgent care situation arises. |

| 3. Use an ED treatment plan to optimize the ED experience. |

| 4. Work on communication with ED providers. |

| 5. Work on communication post ED visits. |

Strengths

Our study reflects perceptions by headache specialists with a specific interest in the care our most challenging patients receive outside the clinic setting. Participants are part of a national society and thus their opinions reflect the diversity of practice throughout the country. Our response rate of 52.1% is high for physician surveys where response rates are usually lower. Other studies published in our journal have had lower response rates. For example, the study by Robbins M et al. “Procedural Headache Medicine in Neurology Residency Training: A Survey of US Program Directors” had a 42.6% response rate. 14 The study by Evans R et al “A Survey of Headache Medicine Specialists on Career Satisfaction and Burnout” had a response rate of 17%. 15

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. 1. Our study assessed those who were members of the American Headache Society. Thus, it is likely that the EDs in which they work are more likely to have ED protocols in place compared to EDs nationwide which may not have a headache specialist. 2. Our response rate of just over 50% may have been with more motivated headache specialists and could bias our results. 3. Most of the participants work in an academic environment and thus the results may not be generalizable to private practice settings. 4. We do not have patient level data so we are limited in making conclusions about the appropriateness of whether the providers should be using preventive medications more or less frequently than they report in the survey.

Conclusions

Headache specialists are generally dissatisfied with the care their patients receive in the ED. There may be areas of improvement needed for better communication between the ED and the headache specialist as to what happens to patients in the ED and what the follow-up plan entails. Future topics of study could include the preferred methods of communication between headache specialists and ED providers, including, but not limited to providing patients with written recommendations to bring with them when going to the ED or Urgent Care. When appropriate, EDs might benefit from structured order sets or guidelines for the management of primary headache disorders in the ED setting, generated either by that institution’s catchment of headache specialists/neurologists or by recognized bodies of experts such as the American Headache Society.

Figure 1:

Flow Chart Outlining Participation

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mia Minen received the Practice Research Training Fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology-American Brain Foundation which provided her with salary support to have the time to conduct research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Minen-No conflict

Ortega-No conflict

Lipton:

Cowan:

Contributor Information

Mia T. Minen, NYU Langone Headache Center, NY, NY.

Emma Ortega, City College, CUNY, NY, NY.

Richard Lipton, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Hospital.

Robert Cowan, Stanford Health Systems, San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.Minen MT, Loder E, Friedman B. Factors associated with emergency department visits for migraine: An observational study. Headache. 2014;54(10):1611–1618. doi: 10.1111/head.12461 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, Armstrong MJ, et al. The American Academy of Neurology’s top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Solorzano C, et al. Randomized study of IV prochlorperazine plus diphenhydramine vs IV hydromorphone for migraine. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2075–2082. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004642 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of adults with acute migraine in the emergency department: The American Headache Society evidence assessment of parenteral pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016;56(6):911–940. doi: 10.1111/head.12835 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, Minen MT, Restivo A, Gallagher EJ. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: An analysis of the national hospital ambulatory medical care survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(4):301–309. doi: 10.1177/0333102414539055 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(4 Headache):953–972. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000192 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Stone AM, Lainez MJ, Sawyer JP, Disability in Strategies of Care Study group. Stratified care vs step care strategies for migraine: The disability in strategies of care (DISC) study: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2599–2605. doi: joc00804 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy LH, Cowan RP. Comparison of parenteral treatments of acute primary headache in a large academic emergency department cohort. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(9):807–815. doi: 10.1177/0333102414557703 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley NE, Tepper DE. Rescue therapy for acute migraine, part 3: Opioids, NSAIDs, steroids, and post-discharge medications. Headache. 2012;52(3):467–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley NE, Tepper DE. Rescue therapy for acute migraine, part 2: Neuroleptics, antihistamines, and others. Headache. 2012;52(2):292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley NE, Tepper DE. Rescue therapy for acute migraine, part 1: Triptans, dihydroergotamine, and magnesium. Headache. 2012;52(1):114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gindi RM, Cohen RA, Kirzinger WK. Emergency room use among adults aged 18–64: Early release of estimates from the national health interview survey, January–June 2011. CDC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Emergency Physicians. Practice Management/Standardized protocols for optimizing emergency department care. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Standardized-Protocols-for-Optimizing-Emergency-Department-Care/#sm.000d3pduu1d86f2nr1b2jwj7dlz0f. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- 14.Robbins MS, Robertson CE, Ailani J, Levin M, Friedman DI, Dodick DW. Procedural headache medicine in neurology residency training: A survey of US program directors. Headache. 2016;56(1):79–85. doi: 10.1111/head.12695 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RW, Ghosh K. A survey of headache medicine specialists on career satisfaction and burnout. Headache. 2015;55(10):1448–1457. doi: 10.1111/head.12708 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]