Abstract

Complex rule-based auditory processing is abnormal in individuals with long-term schizophrenia (SZ), as demonstrated by reduced mismatch negativity (MMN) to deviants in rule-based patterns and reduced auditory sustained potential (ASP) that appears when grouping tones together. Together this suggests deficits later in the auditory processing hierarchy in Sz. Here, MMN and ASP were elicited by deviations from a complex zig-zag pitch pattern that cannot be predicted by simple linear rules. Twenty-seven SZ and 26 matched healthy controls (HC) participated. Frequent groups of patterns contained eight tones that zig-zagged in a two-up one-down pitch-based paradigm. There were two deviant patterns: the final tone was either higher in pitch than expected (creating a jump in pitch) or was repeated. Simple MMN to pitch-deviants among repetitive tones was measured for comparison. Sz exhibited a smaller pitch MMN compared to HC as expected. HC produced a late MMN in response to the repeat and jump-deviant and a larger ASP to the standard group of tones, all of which were significantly blunted in SZ. In Sz, the amplitude of the late complex MMN was related to neuropsychological functioning, whereas ASP was not. ASP and late MMN did not significantly correlate in HC or in Sz, suggesting that they are not dependent on one another and may originate within distinct processing streams. Together this suggests multiple deficits later in the auditory sensory-perceptual hierarchy in Sz, with impairments evident in both segmentation and deviance detection abilities.

Keywords: EEG ERP, audition, novelty, deviance detection

Graphical Abstract

We investigated complex rule-based novelty detection in individuals with chronic schizophrenia by measuring mismatch negativity (MMN) and the auditory sustained potential (ASP) to deviant tones in a complex zig-zag pitch pattern that cannot be predicted by simple linear rules. Both the ASP and late MMN were significantly reduced in schizophrenia compared to controls, suggesting deficits later in the auditory hierarchy responsible for auditory segmentation and deviance detection abilities.

Introduction

Individuals with schizophrenia show deficits in neural measures of auditory deviance detection, one of them being the mismatch negativity (MMN), and the reduction in MMN in schizophrenia is one of the most robust deficits in the field (Umbricht & Krjles, 2005; Erickson et al., 2016). The MMN is a pre-attentive event-related potential (ERP) that appears in response to a rare deviant stimulus. Typically, this is measured by presenting frequent identical tones, and occasionally either presenting tones of a different pitch or of a different duration. The MMN elicited from the deviant pitch tone is reduced in schizophrenia with an effect size of 0.94, and an effect size of 1.23 for the MMN to deviant duration tones (Umbricht & Krjles, 2005). The MMN is related to measures assessing daily functioning, as measured using the Global Assessment of Functioning, and the ability to live independently (Light et al., 2007). MMN has also been shown to be related to measures of cognition in schizophrenia – specifically measures of memory, verbal learning, and general cognition (as measured using the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery; Thomas et al., 2017), and with IQ (Salisbury et al., 2017). Together, this demonstrates that impaired MMN could be related to impairments in a wide range of cognitive domains. The mechanism driving MMN generation was originally described to be from sensory memory (Näätänen, 1990), and was later described as being part of an internal error-detection model (Winkler, 2007; Winkler et al., 2009). However, repeating frequent identical tones is likely to evoke adaptation in auditory cortex, and so the MMN may contain signal associated with a release from adaptation to the deviant tone (May & Tiitinen, 2004; 2010). One of these mechanisms (either sensory adaptation or error-detection modeling) is likely to be abnormal in schizophrenia. Using the typical single parameter-deviant paradigm makes it difficult to dissociate between the two mechanisms.

One way to dissociate these processes is to use paradigms that cannot be explained by sensory adaptation (specifically, by not repeating identical tones). Deviants in complex patterns without any single frequent tone can elicit MMN. For example, deviant pairs of tones that descend in pitch compared to frequent pairs of tones that ascend in pitch evoke a MMN (hereby referred to as a complex MMN) in healthy controls (Gumenyuk et al., 2003; Paavilainen et al., 1998; 1999; van Zuijen et al., 2006; Korzyukov et al., 2003; Tervaniemi et al., 1999). Detecting deviant stimuli in complex patterns relies on the ability to segment the stimuli into groups based on a rule – the only difference between the frequent and infrequent pairs is that the pitch is expected to increase but decreases instead. Individuals with long-term schizophrenia produce significantly smaller MMN to descending pairs of tones compared to controls (Salisbury et al., 2018). Similarly, controls exhibit MMN to a missing tone from frequent groups of six tones (Salisbury, 2012), which is significantly smaller in individuals with long-term schizophrenia (Salisbury & McCathern, 2016) and in early-course schizophrenia (Rudolph et al., 2016).

However, as pattern complexity increases, more than one MMN may emerge. MMN to simple pitch deviants elicit a MMN around 150 ms after deviant-onset. In healthy controls, one study reported an early MMN between 150-200 ms and a late MMN between 350-450 ms after a deviant complex tone (Korpilahti et al., 2001). A second study reported two MMNs to deviant descending pairs of tones compared to frequent ascending pairs of tones: one at 146 ms and a second at 340 ms after deviant-onset (Zachau et al., 2005). A third study reported an early MMN (150-200 ms) and a late MMN (~250 ms) after the onset of an unexpected additional tone (Recasens et al., 2014). These multiple MMNs may indicate deviance detection at multiple stages of the auditory hierarchy (Escera & Malmierca, 2014; Grimm & Escera, 2012; MacLean & Ward, 2014).

In schizophrenia, the late complex MMN appears to be significantly impacted. Haigh et al. (2016) presented groups of identical tones, with the deviant containing an additional sixth tone, thus violating the abstract grouping rule. The controls produced two MMNs: one within the expected time interval (~150 ms after deviant-onset), and a second ‘late’ MMN (~350 ms). However, the individuals with schizophrenia only produced an early MMN, suggesting deficits in later stages of the auditory detection system hierarchy. Similarly, Haigh et al. (2017) measured complex MMN to two abstract pitch-rule paradigms, and found that both paradigms elicited an early MMN (~ 150 ms after deviant-onset) in controls and in schizophrenia and a late MMN (400-500 ms after deviant-onset) in controls only. This demonstrates that individuals with schizophrenia show consistent deficits in novelty detection that manifest later in the auditory processing hierarchy and are not necessarily due to degraded information from early auditory processing.

The reduced complex MMN in schizophrenia could be due to deficits in being able to segment the auditory stream into groups. One ERP measure of auditory segmentation is the emergence of an auditory sustained potential (ASP) that lasts for the duration of an abstracted pattern. The ASP is an ERP of auditory scene analysis which occurs later in the perceptual hierarchy where sounds are segregated and integrated depending on the context of the sounds (Bergen,1994). The ASP builds over the first several presentations and is disrupted when a deviant tone is presented. The ASP is reduced in individuals with schizophrenia (Coffman et al., 2016), and is related to impairments in measures of neuropsychological functioning, such as working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, and social cognition. Together this suggests specific deficits in novelty detection potentially related to the ability to segment the auditory environment.

However, a criticism of using patterns that are based on a single rule (for example, number of tones in a group, or continuous increases in pitch) is that these patterns are still based on a simple linear rule, similar to simple MMN, and so may still be reliant on early auditory processing. Korzyukov and colleagues (2003) found that primary auditory cortex contributed to the paired-tones MMN, but that the distribution of the activation across auditory cortex differed compared to simple pitch-tone MMN, in a way that suggested greater overall recruitment. Therefore, early sensory processing could still be contributing to subsequent processing of deviance detection in simple rule-based patterns and could help generate the late MMN. This deviant might explain why previous studies found an early (more sensory-related) MMN, in line with May & Tiitinen (2007; 2010), and a late (perhaps more cognitive-related) MMN in controls (Näätänen, 1990; Winkler 2007; Winkler et al., 2009; Haigh et al., 2016; Haigh et al., 2017). If this is true, then it is still unclear whether deficits in deviance detection in schizophrenia are due to early sensory abnormalities or if they are due to deficits later in the auditory hierarchy. Therefore, using a more complex rule-based pattern may further stress the auditory processing hierarchy, and further exacerbate the difference between patients and controls.

In the current study, we measured simple MMN to single pitch deviants (Experiment 1) and late complex MMN in a two-up one-down pitch-based paradigm (simulating a zig-zag staircase pattern), where the deviant was either a repeated tone or was higher in pitch than expected (Experiment 2). The zig-zag pattern cannot be predicted by a simple linear rule (e.g. ascending pitch), but by a constant switching of ascending and descending pitches. We also measured the ASP to the standard pattern to ascertain the relationship between pure novelty detection and the ability to segment the acoustic scene. Deficits in both the late complex MMN and the ASP to a complex-rule based pattern would demonstrate specific deficits in processing later in the auditory hierarchy. Finally, we will run exploratory tests on the relationship between the late MMN and ASP with measures of neuropsychological functioning to investigate if poor auditory processing reflected impaired behavioral functioning, and if so, in what domain.

Experiment 1

Methods

Participants

Twenty-seven participants with schizophrenia (Sz) were compared with 26 healthy control (HC) participants who were matched for age, gender, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999) IQ, and parental socioeconomic status. Twenty-three Sz had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (paranoid=9; undifferentiated=8; residual=5; disorganized=1), and four had schizoaffective disorder (depressed subtype).

All participants were recruited from Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC) inpatient and outpatient services. All Sz had at least 5 years length of illness, or were hospitalized at least three times for psychosis.

All subjects had normal hearing as assessed by audiometry, at least nine years of schooling, and an IQ over 85. None of the participants had a history of concussion or head injury with sequelae, history of alcohol or drug addiction, detox in the last five years, or neurological comorbidity. The 4-factor Hollingshead Scale was used to measure socioeconomic status (SES) in participants and in their parents. As expected, Sz had lower SES than HC, consistent with social and occupational impairment as a disease consequence (see Table 1 for demographic measures). All participants provided informed consent and were paid for participation. All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB and conformed with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Demographic and diagnostic information for the Sz and HC groups, with t/chi-square statistics and p-values for group comparisons. Medication is listed in Chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalents. Dosages primarily from Andreasen et al. (2010), and remaining dosages from Gardner et al. (2010).

| Sz | HC | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 27 | 26 | |

| Age | 34.98 ±7.61 | 31.82 ±10.51 | t(51)=1.26, p=.213 |

| Gender (M/F) | 17/10 | 17/9 | X2 (1)=.03, p=.854 |

| Handedness1 (R/L) | 24/2 | 24/2 | X2(1)<.01, p>.999 |

| IQ | 103.59 ±14.36 | 107.85 ±11.64 | t(51)=1.18, p=.243 |

| SES | 31.19 ±13.83 | 43.04 ±11.57 | t(51)=3.38, p=.001 |

| Parental SES | 36.70 ±13.88 | 42.08 ±11.42 | t(51)=1.54, p=.131 |

| MCCB (MATRICS)1 | 18.05 ±24.90 | 46.87 ±26.44 | t(49)=3.95, p<.001 |

| GFS (social) | 5.15 ±1.56 | 8.87 ±0.30 | t(28.0)=12.14, p<.001 |

| GFS (role) | 4.15 ±2.11 | 8.85 ±0.34 | t(27.4)=11.43, p<.001 |

| Medication (CPZ) | 356.58 ±264.83 | ||

| Length of illness (years) | 13.07 ±7.55 | ||

| PANSS Total | 70.65 ±13.59 | ||

| PANSS Positive | 15.27 ±5.20 | ||

| PANSS Negative | 19.69 ±6.26 | ||

| SAPS (global items) | 12.74 ±3.18 | ||

| SAPS (symptom items) | 37.63 ±10.49 | ||

| SANS (global items) | 4.37 ±3.12 | ||

| SANS (symptom items) | 9.33 ±8.17 | ||

| UPSA communication | 7.15 ±1.71 | ||

| UPSA financial | 8.58 ±1.84 |

One participant did not complete the handedness questionnaire and another did not complete the MATRICS battery.

Diagnostic Assessments

Diagnosis was based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-P). Symptoms were rated using the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS), Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS), and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). All tests were conducted by an expert diagnostician.

Neuropsychological Tests

All participants completed the MATRICS Cognitive Consensus Battery and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). Social functioning was assessed with the Global Functioning Scale (GFS), and the brief UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B). See Table 1 for neuropsychological scores. One Sz did not complete all of the MATRICS battery due to time constraints.

Procedure

Stimuli were generated with Tone Generator (NCH Software), and presented in Presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.). Binaural auditory stimuli were presented at 80 dB using Etymotic 3A insert earphones, with loudness confirmed with a sound meter. Participants watched a silent nature video whilst tones were played over earphones. They were asked to concentrate on the movie and ignore the tones.

Stimuli

Tones of 1 kHz of 50 ms duration with 5ms rise/fall times were presented on 80% of trials. Pitch-deviants (1.2 kHz, 50 ms, 5 ms rise/fall) were presented 10% of the time. At least two standard tones preceded a deviant tone. Tones had a stimulus-onset-asynchrony (SOA) of 330 ms.

EEG Recording

EEG was recorded from a custom 72 channel Active2 high impedance system (BioSemi), comprising 70 scalp sites including the mastoids, 1 nose reference electrode, and 1 electrode below the right eye. The EEG amplifier bandpass was DC to 104Hz (24 dB/octave rolloff) digitized at 512Hz, referenced to a common mode sense site (near PO1). Processing was done off-line with BESA 6 (BESA GMBH) and BrainVision Analyzer2 (Brain Products GMBH). First, using BESA, EEG was filtered between 0.5-20Hz; the relatively high low cutoff was to remove DC drifts and skin potentials, the high cutoff was to remove muscle and other high frequency artifact. Data were visually examined and bad channels were interpolated. ICA was used to remove one vertical and one horizontal EOG component. Eye corrected data were then analyzed in BrainVision Analyzer2 and rereferenced to averaged mastoids.

Data Analysis

Epochs (350ms) were extracted from the EEG based on stimulus triggers, including a 50ms prestimulus baseline. All epochs were baseline corrected, and linear DC detrended between baseline (−50-0ms) and the last 50ms of the epoch to ensure that the data were not skewed by skin potentials and steady-state drift. Epochs were subsequently rejected if any site contained activity ±50μV.

MMN waveforms were calculated by subtracting the ERP waveform in response to the standard tone from the deviant tone ERP waveform. The window for calculating the MMN amplitudes depended on the maximal response for both groups in the grand averages. For the MMN to the simple pitch-deviants, the average voltage was calculated between 105-125ms. Groups did not significantly differ in the number of epochs included in the averages (HC: mean 125.8, std ±52.1; Sz: mean 115.6, std ±46.9; t(50)=0.74, p=.460).

Statistics

Group demographics and neuropsychological scores were compared using t-tests and chi-squared tests where appropriate. MMN analyses utilized repeated-measures ANOVA, with group (Sz, HC) as the between subjects factor, and electrode chain (F or FC) and site (left, central, or right) as within subjects factors. The Huynh-Feldt epsilon was used to correct for multiple comparisons of site. CSD topography of complex MMN was calculated to indicate a possible dipole source. Interpolation was done using spherical splines, with the order of splines set to 4, the maximum degree of Legendre polynomials set to 10, and a default lambda of 1e-5. Two-tailed Spearman’s correlations were used to examine relationships between MMN at FCz (where it was largest) and demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological items. These correlations were exploratory to provide suggestion for future investigations and so were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Values are reported as mean ± std. Significance was attained at p <.05.

Results

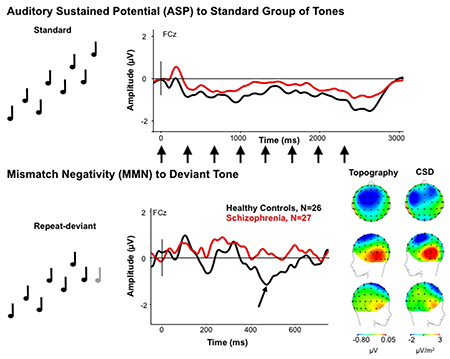

Both HC and Sz showed a large negativity to the higher pitched (deviant) tone compared to the standard pitched-tone (Figure 1A compared to Figure 1B). MMN amplitude was significantly larger in HC (mean −2.27; std ±1.45) than in the Sz group (mean −1.25; std ±1.45; F(1,51)=6.50, p=.014). Scalp topography and CSD maps showed the expected MMN distribution and temporal sources (Figure 1C).

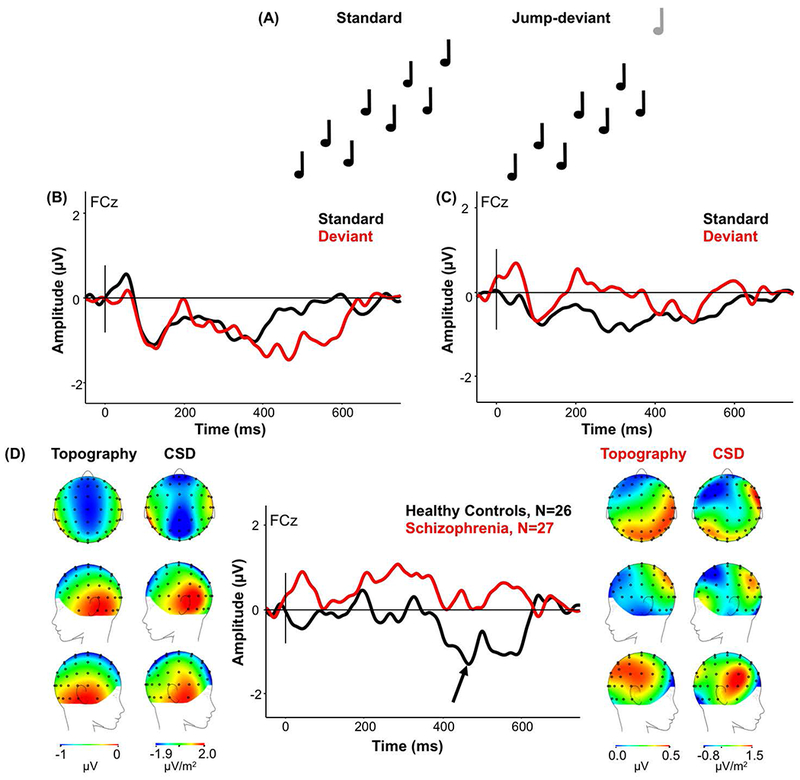

Figure 1.

(A) ERP waveforms in HC in response to the pitch-deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode site. (B) ERP waveforms in Sz in response to the pitch-deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode. (C) The MMN response (standard waveform subtracted from deviant waveform) to the pitch-deviant in HC and Sz. (From Left to Right) Scalp topography and current source density (CSD) maps of the MMN to the pitch-deviant in HC; simple MMN waveform to the pitch-deviant in HC (black) and Sz (red) as indicated by the arrow for FCz electrode; scalp topography and CSD maps to the pitch-deviant in Sz. Scales of topography and CSD maps were adjusted to accurately reflect distribution in each group unconfounded by the main effect.

Correlations with Symptoms and Neuropsychological Measures

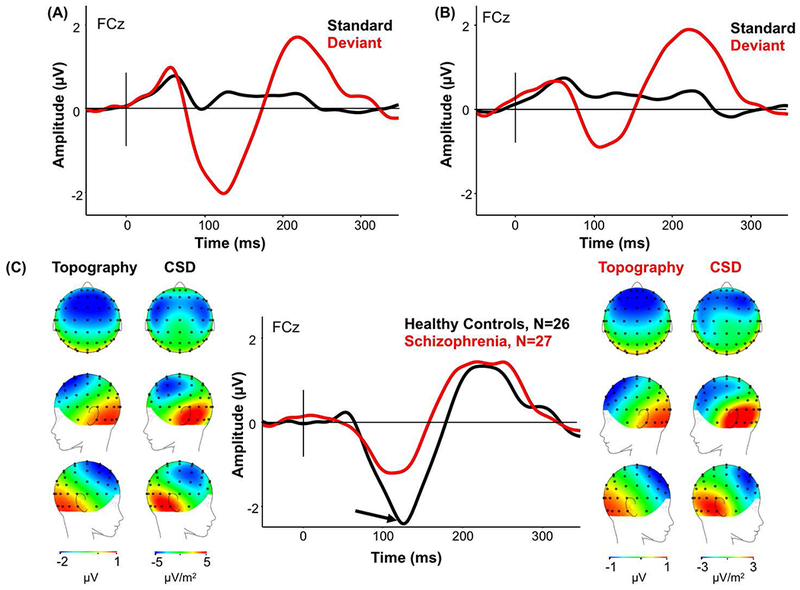

Older HC produced smaller pitch MMN (rs(24)=.46, p=.018), and Sz with higher IQ produced larger pitch MMN (rs(25)=−.44, p=.023; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Correlations between simple pitch MMN and (A) age of participant (in years) and IQ score in HC and Sz; (B) three measures from the MATRICS battery: the continuous pairs task, the attention vigilance task, scores on reasoning and problem solving, the neuropsychological assessment battery, and the brief visual memory test in HC and Sz; (C) medication dosage (CPZ equivalents) and depression scores as measured in the PANSS in Sz only.

HC with larger pitch MMN scored worse on the continuous pairs test in the MATRICS battery (rs(24)=.47, p=.016), attentional vigilance measures (rs(24)=.52, p=.006), and reasoning and problem solving measures (rs(24)=.47, p=.014).

In Sz, smaller pitch MMN was associated with worse performance on reasoning and problem solving measures (rs(25)=−.47, p=.014), on the neuropsychological assessment battery (rs(25)=−.50, p=.008), on the Brief Visual Memory Test (rs(25)=−.45, p=.019), and on measures on the Global Functioning Scale – Role (rs(25)=−.41, p=.033; Figure 2B). However, small pitch MMN was associated with lower depression scores on the PANSS (rs(25)=−.39, p=.046), and those with smaller pitch MMN were on higher doses of antipsychotic medication (rs(25)=.45, p=.019; Figure 2C).

Experiment 1 Discussion

The significant reduction in simple MMN in Sz demonstrates the robust finding of abnormal novelty detection in this sample. The correlations between pitch MMN and MATRICS battery scores in Sz were in line with previous literature that worse pitch MMN is associated with worse cognitive performance (Light et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2017). However, these correlations in HC were surprising, as they suggest that worse cognitive performance is associated with a larger MMN. This may be because MMN is not impaired in controls, and so we may be detecting the occasional correlation that is mediated by another unknown mechanism, but the general trend is that auditory novelty detection is not related to neuropsychological functioning in healthy individuals.

Now that we have demonstrated that this sample of Sz exhibit a significant reduction in pitch MMN, we can examine the complex MMN to a complex pitch-based zig-zag paradigm in the same individuals. The complexity of the pattern is expected to recruit only later auditory processes associated with pure novelty detection and should not be dependent on simple auditory processing. We will also measure group differences in the ASP, and correlate complex MMN with ASP to ascertain if novelty detection is dependent on the ability to segment the acoustic scene.

Experiment 2

Methods

All methods were the same as above with the following differences.

Stimuli

Temporal proximity was used to form discrete groups, with a SOA within groups of 330 ms and an inter-trial interval of 800 ms. The standard pattern consisted of eight tones with ascending pitch of two-up, one-down steps: 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 1.5 kHz, 2.5 kHz, 2 kHz, 3 kHz, 2.5 kHz, 3.5 kHz. 80% of the tone groups were standards. There were two types of deviants: the repeat-deviant was the same as the standard pattern of tones, except the eighth tone was presented at the same frequency as the seventh tone (instead of increasing in frequency by 1 kHz). The jump-deviant was the same as the standard, except the eighth tone was presented 1.5 kHz higher than the seventh tone (instead of 1 kHz as in the standard pattern). Each deviant type was presented 10% of the time. Deviant groups never immediately followed one another.

Data Analysis

For the analysis of the complex MMN, epochs of the last tone in the standard group and of the last tone in the deviant group were extracted (−50 before to 700ms after stimulus onset). All epochs were baseline corrected, and DC detrended between baseline (−50-0 ms) and the last 50 ms of the epoch to ensure that the data were not skewed by skin potentials and steady-state drift. Epochs were subsequently rejected if any site contained activity ±50 μV. Complex MMN waveforms were calculated by subtracting the ERP waveform in response to the standard stimulus from the deviant stimulus waveform. The window for calculating the MMN amplitudes depended on the maximal response for both groups in the grand averages. For the MMN to repeat deviant, two MMNs were detected. The average response for the early MMN was calculated between 190-210ms after stimulus-onset, and for the late MMN, the response was averaged over 400-500 ms after stimulus-onset. Groups did not significantly differ in the number of epochs included in averages (Repeat deviants HC: mean 43.7, std ±7.6; Sz: mean 44.0, std ±5.6; t(51)=0.21, p=.835; Jump deviants HC: mean 43.5, std ±5.4; Sz: mean 43.5, std ±4.5; t(51)=0.34, p=.737).

For the analysis of the ASP, epochs of the standard group of tones were extracted (−100 ms before the start of the first tone in the standard group to 750 ms after the last tone in the group). All epochs were baseline corrected. Epochs were subsequently rejected if any site contained activity ±50 μV. Participants who had more than 40 epochs after artifact rejection were included in the analysis. This meant that two Sz and three HC were excluded. A 1.5 Hz high-pass filter was then applied (consistent with the analysis of the ASP by Coffman et al., 2016), and was calculated from 330 ms after the first tone in the group to the 330 ms after the last tone in the group. Groups did not significantly differ in the number of epochs included in averages (HC: mean 83.8, std ±11.6; Sz: mean 77.2, std ±16.0; t(43.7)=1.65, p=.105).

Results

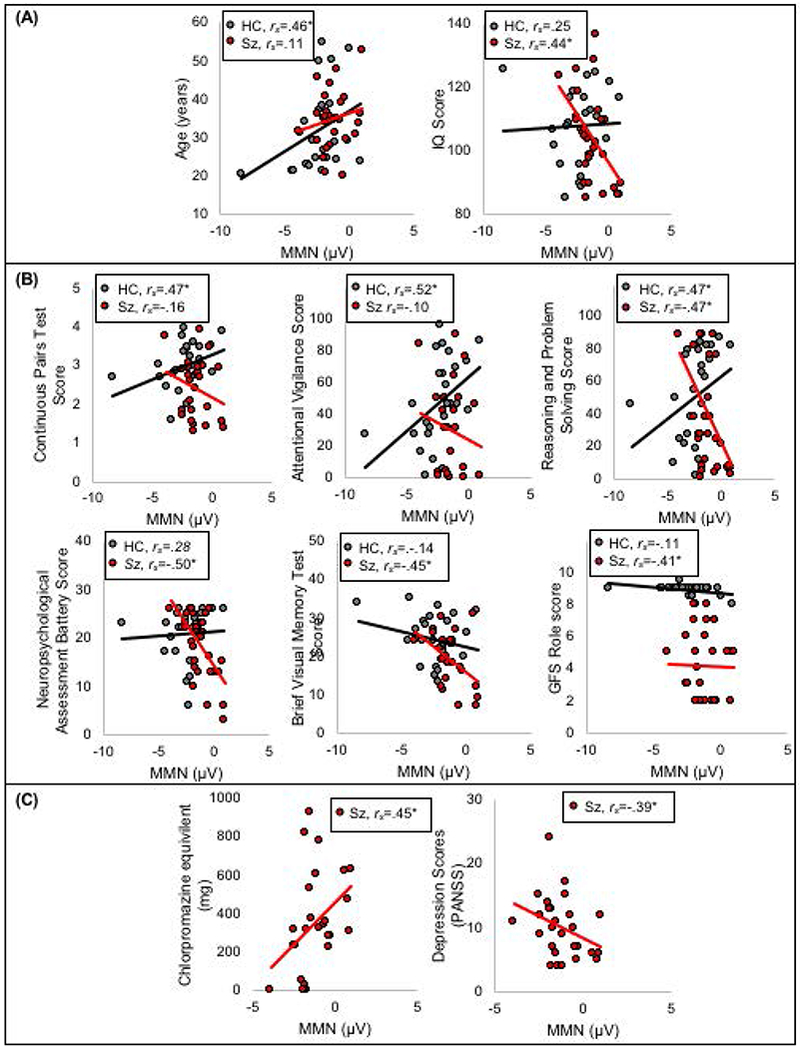

The repeat deviant produced two MMNs in HC compared to the response to the last tone in the standard trial (Figure 3A). Only the early MMN was present in Sz (Figure 3B). There was no significant difference between groups in the amplitude of the early MMN (HC mean −0.57; std ±2.03; Sz mean 0.15; std ±1.96; F(1,51)=1.78, p=.188). However, HC produced a larger late negativity (mean −0.77; std ±1.62) than Sz (mean 0.22; std ±1.62; F(1,51)=4.88, p=.032; Figure 3C). The CSD map of the source of the late MMN HC suggests that the late MMN originated bilaterally from temporal lobe with the right-hand source looking slightly more anterior.

Figure 3.

(A) Standard groups of eight tones with ascending pitch of two-up, one-down steps, and deviant groups with seven tones ascending in pitch with the eighth tone repeating. (B) ERP waveforms in HC in response to the repeat deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode site. Arrows indicate where the extra negativity to the repeat tone appeared. (C) ERP waveforms in Sz in response to the repeat deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode. (D) The MMN response (standard waveform subtracted from the deviant waveform) to the repeat deviant in HC and Sz from the onset of the deviant to show maximal MMN amplitude. (From Left to Right) Scalp topography and current source density (CSD) maps of the MMN to the repeat deviant in HC; MMN waveform to the repeat deviant in HC (black) and Sz (red) as indicated by the arrow for FCz electrode; Scalp topography and CSD maps to the repeat deviant in Sz. Scales of topography and CSD maps were adjusted to accurately reflect distribution in each group unconfounded by the main effect.

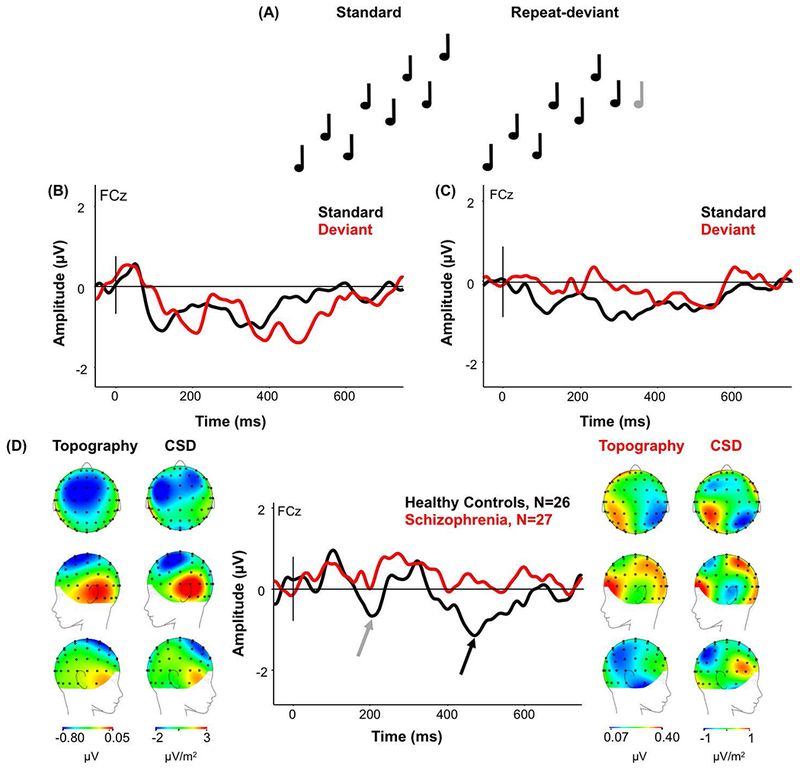

The jump deviant only produced a late negativity in HC compared to the response to the last tone in the standard trial (Figure 4A), which was absent in Sz (Figure 4B). HC produced significantly larger late negativity (mean −0.92; std ±1.78) than Sz (mean 0.14; std ±1.78; F(1,51)=4.72, p=.035) (Figure 4C). The CSD map of the source of the late MMN in HC suggests a more anterior origin than typical MMN responses.

Figure 4.

(A) Standard groups of eight tones with ascending pitch of two-up, one-down steps, and deviant groups with seven tones ascending in pitch with the eighth tone increasing in pitch by three steps (jump deviant). (B) ERP waveforms in HC in response to the jump deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode site. Arrow indicates where the extra negativity to the jump deviant appeared. (C) ERP waveforms in Sz in response to the jump deviant (red) and the standard tone (black) for FCz electrode. (D) The MMN response (standard waveform subtracted from the deviant waveform) to the jump deviant in HC and Sz from the onset of the deviant to show maximal MMN amplitude. (From Left to Right) Scalp topography and current source density (CSD) maps of the MMN to the jump deviant in HC; simple MMN waveform to the jump deviant in HC (black) and Sz (red) as indicated by the arrow for FCz electrode; scalp topography and CSD maps to the jump deviant in Sz. Scales of topography and CSD maps were adjusted to accurately reflect distribution in each group unconfounded by the main effect.

The ASP to the standard groups of tones was significantly larger in HC (mean −.88; std ±0.98) compared to Sz (mean −.40; std ±.65; F(1,46)=4.30, p=.044; Figure 5). However, there was no significant correlation between the amplitude of the ASP and the late MMN to either the repeat deviant (HC: rs(24)=.10, p=.647; Sz: rs(23)=.02, p=.916) or the jump deviant (HC: rs(24)=−.26, p=.239; Sz: rs(23)=.02, p=.936).

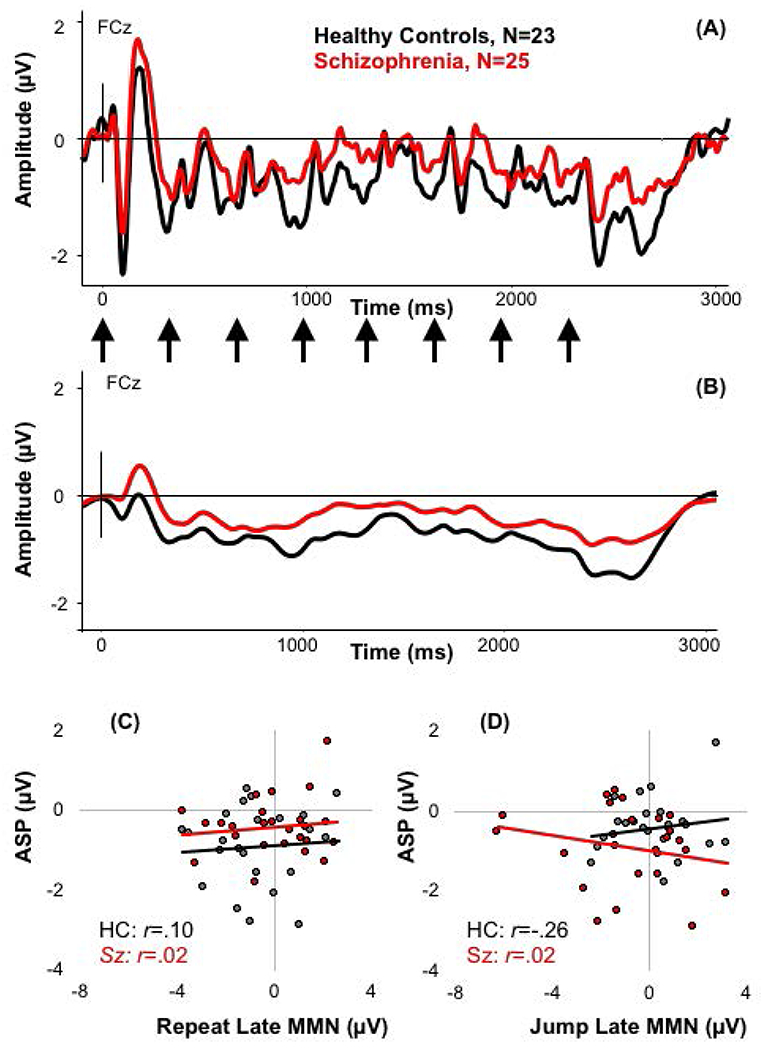

Figure 5.

(A) The waveform to the standard group of tones with the onset of the tones indicated with arrows; (B) the same waveform with the 1.5Hz filter to show the ASP; (C) the relationship between ASP and the late repeat MMN for HC and Sz; (D) the relationship between ASP and the late jump MMN for HC and Sz.

For both HC and Sz, those who produced a larger late repeat MMN also produced a larger late jump MMN (HC: rs(24)=.48, p=.012; Sz: rs(25)=.39, p=.045; Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

(A) Relationship between MMN to the repeat and jump deviants in HC and Sz; (B) correlations between late complex MMN and IQ score, SAPS global symptoms, UPSA financial scores, shown separately for repeat and jump deviants; (C) correlations between late complex MMN and MATRICS measures, including social cognition scores, attentional vigilance scores, scores on the continuous pairs test, the Mayer-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, and the brief visual memory test, shown separately for repeat and jump deviant.

Correlations with Symptoms and Neuropsychological Measures

For Sz, those with higher IQ produced larger late MMNs to the repeat (rs(25)=−.43, p=.024) and the jump deviant (rs(25)=−.53, p=.004). Smaller late repeat MMN was associated with worse global measures of positive symptoms (measured using the SAPS scale) (rs(25)=.39, p=.044), and smaller late jump MMN was associated with worse financial scores on the UPSA scale (rs(25)=−.52, p=.006; Figure 6B). Sz who produced larger late jump MMN scored higher on the MATRICS battery overall (rs(24)=−.45, p=.025), specifically on social cognition measures (rs(24)=−.45, p=.022), measures of attentional vigilance (rs(25)=−.62, p=.001), the continuous pairs task (rs(24)=−.63, p=.001), the Mayer-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (rs(24)=−.42, p=.031), the Brief Visual Memory Test (rs(25)=−.40, p=.041), and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (rs(24)=−.39, p=.047). The only correlation that was significant with the late repeat MMN was with measures of social cognition (rs(25)=−.42, p=.032). The other correlations were in the same direction, but were not significant (Figure 6C). None of the correlations were significant in HC.

There were no significant correlations between the amplitude of the ASP and any symptom or neuropsychological scores.

Experiment 2 Discussion

The late complex MMN to both the repeat and the jump deviant tone, and the ASP to the standard groups of tones were all significantly reduced in Sz. In addition, the jump deviant did not produce an early MMN, suggesting that detecting the jump deviant did not involve auditory cortex/early sensory processing. This may have been due to the complexity of the deviant: the jump deviant technically followed the rule, but the pitch was higher than expected, and so the deviation was more subtle. Together this supports previous findings that pure novelty detection/later auditory processing is abnormal in Sz (Haigh et al., 2016; Haigh et al., 2017). The amplitude of the MMN to the repeat deviant was related to the amplitude of the MMN to the jump deviant in both HC and in Sz, demonstrating that those who cannot generate a late MMN do so regardless of the type of deviant, and highlights that the late MMN is a reliable and replicable ERP.

However, the ASP did not significantly correlate with either of the late MMNs, suggesting that the two signals are independently impacted in Sz. The ASP also did not significantly correlate with measures of neuropsychological functioning. On the other hand, Sz who showed larger late complex MMN were higher functioning, which is again is consistent with the literature showing a relationship with simple MMN (Light et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2017). The relationship was weaker with the late complex MMN to the repeat deviant than the jump deviant, but Figure 5C shows that the correlations were similar, but slightly weaker, in response to the repeat deviant. The late complex MMN also correlated with IQ, emphasizing the need to match groups on full-scale IQ – if groups are matched then any additional difference in late complex MMN is due to the disease and is not confounded by differences in intelligence.

General Discussion

In response to a complex zig-zag pitch-based pattern deviant, HC produced a late complex MMN in response to the repeat and the jump-deviant, whereas the late complex MMN was significantly smaller in Sz. Individuals who produced a large MMN to the repeat-deviant also produced a large MMN to the jump-deviant, and this was the case for HC and for Sz, demonstrating a reliable late MMN signal regardless of deviant-type. The ASP was also significantly reduced in Sz, consistent with previous reports (Coffman et al., 2016), but size of the late MMN was not related to the ASP, demonstrating that these two signals are not dependent on each other. The MMN to the jump deviant did not evoke an early MMN suggesting that early (sensory) auditory processing is not necessary for generating a late complex MMN. The presence of an early MMN to the repeat deviant may have been due to the fact that an identical tone was presented, but was unexpected, hence some recruitment of early auditory processing to produce an early MMN. Together this demonstrates deficits in pure novelty detection in Sz, independent of any low-level auditory abnormalities.

The findings of reduced complex late MMN in Sz replicate those reported by Haigh et al. (2017), who also showed reduced late complex MMN to pitch-based deviants (although the complexity of the pattern was simpler than in the current study). A late complex MMN was also observed in HC to violations in a group-based rule (Haigh et al., 2016), suggesting that (1) the late complex MMN can be elicited in HC by a variety of different pattern deviants, and (2) that Sz are unable to produce a late MMN. These results indicate a specific deficit in later parts of the hierarchical auditory deviant detection system in Sz (Escera & Malmierca, 2014; Grimm & Escera, 2012; MacLean & Ward, 2014).

In the current study, the late MMN appears to be localized to more anterior regions compared to either the early complex MMN to the repeat-deviant or the simple pitch MMN. From the CSD maps, it is difficult to tell whether the late complex MMN originates solely from auditory cortex with more widespread auditory cortex activation (similar to the results reported by Korzyukov et al., 2003), or whether there is a more distributed system coming online. It is less likely that it is the former, as the jump deviant did not evoke an early complex (potentially more sensory-based) MMN, and so primary auditory cortex is unlikely to have helped with generating a deviance detection signal. There is some evidence that a more distributed system is engaged in complex deviance detection: simple deviants evoked a large early MMN that localized to primary auditory cortex, whereas complex deviants evoked a late MMN that located to numerous brain areas (Alho, 1995; Recasens et al., 2014) including bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Bekinschtein et al., 2009). The complexity of the pattern deviant may require other parts of the brain to come online to help detect the pattern deviant. It could be this distributed system that is under-active in Sz, causing the deficit in pure novelty detection.

There is also a discrepancy in the size of the complex MMNs compared to the simple MMN, with the simple MMN being much larger in amplitude than the complex (early or late) MMNs. Again, this could be due to the complexity of the pattern. The complex pattern could evoke MMNs from multiple parts of the auditory hierarchy, which each produce a small error-detection signal. However, the simplicity of the simple pitch-deviant could mean that most of the deviance processing is completed very quickly by the auditory system, resulting in the multiple MMNs combining to form a single large MMN. Systematically manipulating the complexity of the pattern deviant could ascertain how the size, number, and location of the MMN changes.

The late complex MMN was related to general neuropsychological functioning in Sz: the healthier/larger the late MMN, the higher functioning they were (as measured in the MATRICS battery). For the simple pitch MMN, the higher functioning Sz also produced a larger simple MMN; however, for HC, those with healthier simple MMN had worse performance on several MATRICS measures, and none of the correlations were significant with late complex MMN, suggesting that this relationship in HC is less stable across measures of MMN. These correlations were not adjusted for multiple corrections and so need to be verified with future studies. There was no significant correlation between ASP and measures of neuropsychological functioning, which contradicts the previous findings of reduced working memory, verbal and visual learning etc. correlating with poorer ASP amplitude. It is possible that the ASP signals were too small in Sz due to the complexity of this paradigm, and so were too noisy to produce reliable correlations.

Deficits in later auditory processing (including deviance detection) in Sz could have a direct impact on daily functioning. If an individual has difficulties in identifying changes in their environment, for example, missing changes in pitch in speech that indicate emotion (Jahshan et al., 2015), then this could lead to abnormal social behaviors (Leitman et al., 2005). The correlations between late complex MMN and scores in neuropsychological tests, suggest that deficits in novelty detection could have an impact on general functioning. Therefore, medications or treatments that improve daily functioning in Sz may also improve novelty detection abilities.

Interestingly, the late MMN was not related to the ASP. If the ASP signals the ability to segment the acoustic environment, and segmentation is necessary to detect pattern deviants, then the two signals would be expected to correlate. It is possible that the ASP is related to segmentation, but novelty processing does not rely on this signal to help detect deviance. Alternatively, the two signals could originate from different sources, and it is the connections between auditory cortex and other areas in the auditory hierarchy that are deficient in Sz. Studies focusing on source localization of the ASP and late complex MMN may be able to further disentangle if the two signals are related.

In conclusion, the late complex MMN and ASP are blunted in Sz. This is the third of such studies that have shown late MMN deficits to deviants in abstract rule-based patterns (Haigh et al., 2016; Haigh et al., 2017), demonstrating deficits in novelty detection mechanisms that are not dependent on the type of complex pattern deviant. In addition, the late complex MMN was related to measures of general functioning, suggesting that deviance detection may be related to the underlying pathology in Sz.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH R01 grant (MH094328) to DFS.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Accessibility Statement

Data will be available through the National Institute of Mental Health after publication of the results.

References

- Alho K (1995) Cerebral Generators of Mismatch Negativity (MMN) and Its Magnetic Counterpart (MMNm) Elicited by Sound Changes. Ear Hear., 16, 38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein TA, Dehaene S, Rohaut B, Tadel F, Cohen L, & Naccache L (2009) Neural signature of the conscious processing of auditory regularities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci , 106, 1672–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman BA, Haigh SM, Murphy TK, & Salisbury DF (2016) Event-related potentials demonstrate deficits in acoustic segmentation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res, 173, 109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MA, Ruffle A, & Gold JM (2016) A Meta-Analysis of Mismatch Negativity in Schizophrenia: From Clinical Risk to Disease Specificity and Progression. Biol. Psychiatry, 79, 980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escera C & Malmierca MS (2014) The auditory novelty system: an attempt to integrate human and animal research. Psychophysiology, 51, 111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm S & Escera C (2012) Auditory deviance detection revisited: Evidence for a hierarchical novelty system. Int. J. Psychophysiol, 85, 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumenyuk V, Korzyukov O, Alho K, Winkler I, Paavilainen P, & Näätänen R (2003) Electric brain responses indicate preattentive processing of abstract acoustic regularities in children. Neuroreport, 14, 1411–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh SM, DeMatties M, Coffman BA, Murphy TM, Butera CD, Ward KL, Leiter-McBeth JR, & Salisbury DF (2017). Mismatch negativity to pitch pattern deviants in schizophrenia. European Journal of Neuroscience, 46(6), 2229–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh SM, Coffman BA, Murphy TK, Butera CD, & Salisbury DF (2016) Abnormal auditory pattern perception in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res, 176, 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahshan C, Wynn JK, & Green MF (2015) Relationship between auditory processing and affective prosody in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res, 143, 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpilahti P, Krause CM, Holopainen I, & Lang AH (2001) Early and Late Mismatch Negativity Elicited by Words and Speech-Like Stimuli in Children. Brain Lang, 76, 332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzyukov OA, Winkler I, Gumenyuk VI, & Alho K (2003) Processing abstract auditory features in the human auditory cortex. Neuroimage, 20, 2245–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitman DI, Foxe JJ, Butler PD, Saperstein A, Revheim N, & Javitt DC (2005) Sensory Contributions to Impaired Prosodic Processing in Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry, 58, 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light GA, Swerdlow NR, & Braff DL (2007) Preattentive Sensory Processing as Indexed by the MMN and P3a Brain Responses is Associated with Cognitive and Psychosocial Functioning in Healthy Adults. J. Cogn. Neurosci, 19, 1624–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean SE & Ward LM (2014) Temporo-frontal phase synchronization supports hierarchical network for mismatch negativity. Clin. Neurophysiol, 125, 1604–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ & Tiitinen H (2004) Auditory scene analysis and sensory memory: the role of the auditory N100m. Neurol. Clin. Neurophysiol, 2004, 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJC & Tiitinen H (2010) Mismatch negativity (MMN), the deviance-elicited auditory deflection, explained. Psychophysiology, 47, 66–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen R (1990) The role of attention in auditory information processing as revealed by event-related potentials and other brain measures of cognitive function. Behav. Brain Sci, 13, 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Paavilainen P, Jaramillo M, & Näätänen R (1998) Binaural information can converge in abstract memory traces. Psychophysiology, 35, 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavilainen P, Jaramillo M, Näätänen R, & Winkler I (1999) Neuronal populations in the human brain extracting invariant relationships from acoustic variance. Neurosci. Lett, 265, 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recasens M, Grimm S, Wollbrink A, Pantev C, & Escera C (2014) Encoding of nested levels of acoustic regularity in hierarchically organized areas of the human auditory cortex. Hum. Brain Mapp, 35, 5701–5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph ED, Ells EML, Campbell DJ, Abriel SC, Tibbo PG, Salisbury DF, & Fisher DJ (2015) Finding the missing-stimulus mismatch negativity (MMN) in early psychosis: Altered MMN to violations of an auditory gestalt. Schizophr. Res, 166, 158–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury DF (2012) Finding the missing stimulus mismatch negativity (MMN): Emitted MMN to violations of an auditory gestalt. Psychophysiology, 49, 544–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury DF & McCathern AG (2016) Abnormal Complex Auditory Pattern Analysis in Schizophrenia Reflected in an Absent Missing Stimulus Mismatch Negativity. Brain Topogr, 29, 867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury DF, McCathern AG, Coffman BA, Murphy TK, & Haigh SM (2018) Complex mismatch negativity to tone pair deviants in long-term schizophrenia and in the first-episode schizophrenia spectrum. Schizophr. Res, 191, 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury DF, Polizzotto NR, Nestor PG, Haigh SM, Koehler J, & McCarley RW (2017) Pitch and Duration Mismatch Negativity and Premorbid Intellect in the First Hospitalized Schizophrenia Spectrum. Schizophr. Bull, 43, 407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervaniemi M, Radil T, Radilova J, Kujala T, & Näätänen R (1999) Pre-Attentive Discriminability of Sound Order as a Function of Tone Duration and Interstimulus Interval: A Mismatch Negativity Study. Audiol. Neurotol, 4, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Green M, Hellemann G, & et al. (2017) Modeling deficits from early auditory information processing to psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 74, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D & Krljes S (2005) Mismatch negativity in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res, 76, 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zuijen TL, Simoens VL, Paavilainen P, Näätänen R, & Tervaniemi M (2006) Implicit, Intuitive, and Explicit Knowledge of Abstract Regularities in a Sound Sequence: An Event-related Brain Potential Study. J. Cogn. Neurosci., 18, 1292–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1999) Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler I (2007) Interpreting the mismatch negativity. J. Psychophysiol, 21, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler I, Denham SL, & Nelken I (2009) Modeling the auditory scene: predictive regularity representations and perceptual objects. Trends Cogn. Sci, 13, 532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachau S, Rinker T, Körner B, Kohls G, Maas V, Hennighausen K, & Schecker M (2005) Extracting rules: early and late mismatch negativity to tone patterns. Neuroreport, 16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]