Abstract

Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4) is the only enzyme capable of reducing toxic lipid hydroperoxides in biological membranes to the corresponding alcohols using GSH as the electron donor. GPx4 is the major inhibitor of ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic and iron-dependent programmed cell death pathway, which has been shown to occur in various neurological disorders with severe oxidative stress. In this study, we investigate whether GPx4 expression is altered in multiple sclerosis (MS) and its animal model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). The results clearly show that mRNA expression for all three GPx4 isoforms (cytoplasmic, mitochondrial and nuclear) decline in MS gray matter and in the spinal cord of MOG35–55 peptide-induced EAE. The amount of GPx4 protein is also reduced in EAE, albeit not in all cells. Neuronal GPx4 immunostaining, mostly cytoplasmic, is lower in EAE spinal cords than in control spinal cords, while oligodendrocyte GPx4 immunostaining, mainly nuclear, is unaltered. Neither control nor EAE astrocytes and microglia cells show GPx4 labeling. In addition to GPx4, two other negative modulators of ferroptosis (γ-glutamylcysteine ligase and cysteine/glutamate antiporter), which are critical to maintain physiological levels of glutathione, are diminished in EAE. The decrease in the ability to eliminate hydroperoxides was also evidenced by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and the reduction in the proportion of the docosahexaenoic acid in non-myelin lipids. These findings, along with presence of abnormal neuronal mitochondria morphology, which includes an irregular matrix, disrupted outer membrane and reduced/absent cristae, are consistent with the occurrence of ferroptotic damage in inflammatory demyelinating disorders.

Keywords: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, ferroptosis, glutathione peroxidase 4, lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial damage, multiple sclerosis.

Graphical Abstract

The anti-ferroptosis enzyme GPx4 is critical for the elimination of toxic lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) that arise from iron-catalyzed oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Here, we show that GPx4 mRNA and protein expression are reduced in spinal cord neurons of EAE mice. The accumulation of LOOH in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) spinal cord, demonstrated by the rise in lipid peroxidation products and the decrease in PUFA levels, correlates with the appearance of additional ferroptosis markers such as characteristic damage to mitochondria. These findings provide the basis for the potential use of ferroptosis inhibitors or GPx4 inducer/activators to treat inflammatory demyelinating disorders like MS.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the human CNS, which is characterized by perivascular inflammation, demyelination, oligodendrocyte death and neuronal degeneration (Lucchinetti et al. 1996; Kornek and Lassmann 1999). Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) shares a number of clinical and pathological features with MS and is routinely employed to study the mechanistic bases of disease and to test therapeutic approaches (Gold et al. 2000). In recent years, it has become clear that oxidative stress is a major feature of both disorders (Smith 1999; Gilgun-Sherki et al. 2004; Bizzozero 2009). Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated by activated microglia/macrophages and dysfunctional mitochondria have been shown to oxidize nucleic acids (Vladimirova et al. 1998), proteins (Qi et al. 2006; Smerjac and Bizzozero 2008; Bizzozero 2009; Dasgupta et al. 2013) and lipids (Smerjac and Bizzozero 2008; Dasgupta et al. 2013), and these trigger a number of pathological processes that are ultimately responsible for causing cell death and tissue damage.

Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPx4) is an intracellular, selenium-containing antioxidant enzyme that reduces peroxidized phospholipids in biological membranes to the corresponding alcohols using glutathione (GSH) as substrate (Thomas et al. 1990). The enzymatic reduction of phospholipid hydroperoxides is unique to GPx4 and cannot be carried out by the other glutathione peroxidases, thus making this enzyme critical for downregulating the levels of toxic lipid hydroperoxides (Imai and Nakagawa 2003). There are 3 different GPx4 isoforms that derive from a single gene (Kelner and Montoya 1998; Boschan et al. 2002) – namely, the cytoplasmic isoform (c-GPx4, 170 aa / 19.5 kDa), the mitochondrial isoform (m-GPx4, 197 aa / 22.2 kDa) and the nuclear isoform (n-GPx4, 253 aa / 29.2kDa). GPx4 has been shown to prevent apoptosis by inhibiting peroxidation of the mitochondrial phospholipid cardiolipin, which binds to and keeps cytochrome c within mitochondria (Nomura et al. 2000). In addition, GPx4 decreases the activation of 12/15-lipoxygenase, inhibiting the translocation of the apoptosis-inducing factor from the mitochondria to the nucleus and preventing DNA damage (Seiler et al. 2008). Recently, GPx4 has been identified as a critical regulatory factor in ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic and iron-dependent programmed cell death pathway (Dixon et al. 2012; Cardoso et al. 2017). The recent findings that neuronal GPx4 null mice are not viable (Seiler et al. 2008) and that conditional ablation of GPx4 gene in adult mice causes extensive neurodegeneration (Yo et al. 2012) demonstrate the critical role of this enzyme in neuronal homeostasis.

Ferroptosis is different from apoptosis, necroptosis and autophagic cell death – both at the morphological and biochemical level (Xie et al. 2016). Morphologically, ferroptosis is characterized by the presence of smaller than normal mitochondria with condensed membrane densities, reduced or vanished cristae, and ruptured outer membrane. Biochemically, ferroptosis is distinguished by accumulation of lipid peroxidation products that arise from iron-catalyzed oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and can be pharmacologically inhibited by iron chelators and lipid peroxidation inhibitors. Interestingly, many of these features are present in MS and EAE, suggesting that ferroptotic cell death may be taking place in these disorders. The goal of this study was to determine if levels of the ferroptosis inhibitor GPx4 are reduced in demyelinating disorders and, second, to identify additional ferroptosis markers in EAE. The results clearly show that mRNA expression for all three GPx4 isoforms decline in MS brain and EAE spinal cord. Furthermore, the amount of GPx4 protein (predominantly in neurons) and of other two negative modulators of ferroptosis (γ-glutamylcysteine ligase and cystine/glutamate antiporter), which are critical to maintain physiological levels of GSH, are diminished in EAE. The decrease in the ability to eliminate hydroperoxides was also evidenced by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products and the reduction in the proportion of docosahexaenoic acid. These findings, along with the presence of abnormal mitochondrial morphology, are consistent with the occurrence of ferroptotic damage – possibly caused by GPx4 deficiency – in inflammatory demyelinating disorders.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

Frozen brain specimens were obtained from the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center (Los Angeles, CA) and from the Rocky Mountain MS Center (Englewood, CO) and were stored at −80°C until use. A detailed description of the diagnosis, cause of death and brain pathology of control and MS cases is shown in Table S.1 and Table S.2, respectively. Handling of human tissues was performed using universal precautions and protocol was approved by the Institutional Human Research Review Committee (study # 13–526). Frozen tissues were brought to −20 ˚C and punches in the normal-appearing GM of the parietal lobe (Brodmann area 7) were made with a Harris Uni-core tissue puncher (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA). Immediately after dissection, tissues were processed for RNA isolation or protein analysis as described below.

Induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

Housing and handling of the animals as well as the euthanasia procedure were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol # 16–200424-HSC). Twenty-four eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Bioproducts (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in the UNM-animal resource facility (ARF). Three to four arriving mice were arbitrarily selected and placed in each cage by an ARF staff member. Animals were acclimated for 1 week before cages were arbitrarily assigned to the control group (12 mice) or the EAE group (12 mice). Mice were immunized by cage group because the weaker (EAE) mice could have trouble competing against healthy (control) mice for access to food and water. One control mouse was lost due to unknown causes before the endpoint of experiment. To induce EAE, animals received a subcutaneous injection into the lower back area of 200µl of MOG35–55 peptide (200µg) (21st Century Biochemicals; Marlborough, MA) in saline mixed with complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) supplemented with 4 mg/ml of heat killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Chondrex Inc; Redmond, WA). Control animals were given CFA without MOG peptide. Two-hours and 48h after EAE induction, all animals received an intraperitoneal injection of 0.3 µg of pertussis toxin (PTX, List Biological Laboratories; Campbell, CA) in 100 µl of saline. Seven days after disease induction mice received a second immunization with MOG35–55 peptide in CFA. No measures were taken to minimize possible pain after disease induction because pain-killers and anti-inflammatory drug may affect the disease course; however, water and food were placed on the cage floor. Animals were weighed and examined daily for the presence of neurological signs. A schematic timeline of the study design is depicted in Fig. 1. At the peak of the disease (i.e. 21–30 days after immunization), EAE mice (n= 12) and CFA-injected controls (n= 11) were euthanized by decapitation. The spinal cords were removed, and the cervical and thoracic sections were processed for RNA extraction or homogenized in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5 containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 2 mM 4,5 dihydroxy-1,3 benzene disulfonic acid, 1 mM dithiothreitol, protease inhibitor cocktail 1 (RPI, Mount Prospect, IL) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (RPI). Protein homogenates were stored at −80°C until use. Protein concentration was assessed with the Bio-Rad DC™ protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard. Lumbar spinal cord sections were used for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and immunohistochemical analysis. It is important to note that blinding was not done from the beginning of the study due to the fact that EAE mice exhibit neurological symptoms and thus can be easily identified. However, tissue samples (RNA, protein lysates and histological sections) were assigned with new serial numbers during all experimental procedures. Sample IDs were only revealed to the investigator after data acquisition. This study was not pre-registered.

Fig. 1-.

Schematic diagram showing the timeline of the EAE study design/procedures.

Reverse transcription and qPCR

RNA was isolated from human brain GM and mouse spinal cord specimens via standard Trizol® (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) extraction followed by isopropanol precipitation. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen). Briefly, RNA was incubated with DNase I (M0303, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) at 37˚C for 15 min. DNase I was then inactivated by addition of 2.4 mM EDTA and heating at 75˚C for 10 min. Reverse transcription of RNA was carried out by incubation with oligo(dT)12–18 primer and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (18064022, Invitrogen) at 42˚C for 50 min, followed by heating the samples at 70˚C for 15 min to terminate the reaction. Gene expression levels were quantified using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (4367659, Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA) with primers against selected targets made by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) (Table 1). cDNAs (20ng) were mixed with 1 µM of each primer and amplified with the Power SYBR Green PCR MasterMix according to the manufacturer’s instruction at 50˚C for 10 min, 95˚C for 10 min and then 40 thermal cycles of 95˚C/15 sec and 60˚C/1 min. Relative expression was determined using the comparative 2-ΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Gpx4 mRNA levels in mouse spinal cord samples were normalized to the geometric mean of 4 reference genes (Gapdh, Hprt1, Rplp0 and Rn18s) (Vandesompele et al. 2002). GPx4 mRNA levels in the human samples normalized to h-GAPDH.

Table 1-.

List of PCR primers used in the study

| Gene name | ||

|---|---|---|

| Human Total GPx4 | Forward | 5’-GCTGTGGAAGTGGATGAAGA −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CAGCCGTTCTTGTCGATGA −3’ | |

| Human Mitochondrial GPx4 | Forward | 5’-CCCGGTACTTGTCCAGGTTA −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CTGCTCTGTGGGGCTCT −3’ | |

| Human Nuclear GPx4 | Forward | 5’-TGACGATGCACACGAAGC −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CGAATGTCCCAAGTCCCA −3’ | |

| Human GAPDH | Forward | 5’-GCGCCCAATACGACCAA −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CTCTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTC −3’ | |

| Mouse Total Gpx4 | Forward | 5’-CGCAGCCGTTCTTATCAATG −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CACTGTGGAAATGGATGAAAGTC −3’ | |

| Mouse Mitochondrial Gpx4 | Forward | 5’-TCCTTGGCTGAGAATTCGTG −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CTTACTTAAGCCAGCACTGC −3’ | |

| Mouse Nuclear Gpx4 | Forward | 5’-GCACACGAAACCCCTGTA −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-GTACTGCAACAGCTCCGA −3’ | |

| Mouse Gapdh | Forward | 5’-TGTGATGGGTGTGAACCACGAGAA-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-GAGCCCTTCCACAATGCCAAAGTT-3’ | |

| Mouse Hprt1 | Forward | 5’-TGGGCTTACCTCACTGCTTT-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CTAATCACGACGCTGGGACT-3’ | |

| Mouse Rplp0 | Forward | 5’-TCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCA −3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-CTTTATCAGCTGCACATCACTCAGA −3’ | |

| Mouse Rn18s | Forward | 5’-GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG-3’ |

| Reverse | 5’-GGCCTCACTAAACCATCCAA-3’ | |

Western blot analysis

Proteins (5 μg) from tissue homogenates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 4–20% Mini-Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA) and were blotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blots were blocked with 3% (w/v) non-fat milk in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.05% (v/v/) Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against GPx4 (1:2000, RRID:AB_2232542, MAB5457, R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN), cystine/glutamate antiporter (xCT) (1:500, RRID:AB_778944, ab37185, Abcam; Cambridge, MA), γ-glutamylcysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLc) (1:1000, RRID:AB_880163, ab53179, Abcam) or GAPDH (1:10000, RRID:AB_627679, sc-32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA). Membranes were rinsed three times in PBS-T and were incubated for 2 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5000, RRID:AB_10015289, 115–035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch; West Grove, PA) or anti-rabbit antibody (1:5000, RRID:AB_2307391, 111–035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the Western Lightning ECL™ kit from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, MA). Films were scanned in a Hewlett Packard Scanjet 4050 and the images were quantified using the NIH ImageJ 1.51 imaging analysis program. Band intensities were normalized by the amount of GAPDH in the respective lanes. All the antibodies used in this study were validated by the suppliers and yielded single bands at the predicted molecular weights on western blots.

Immunohistochemical localization of GPx4.

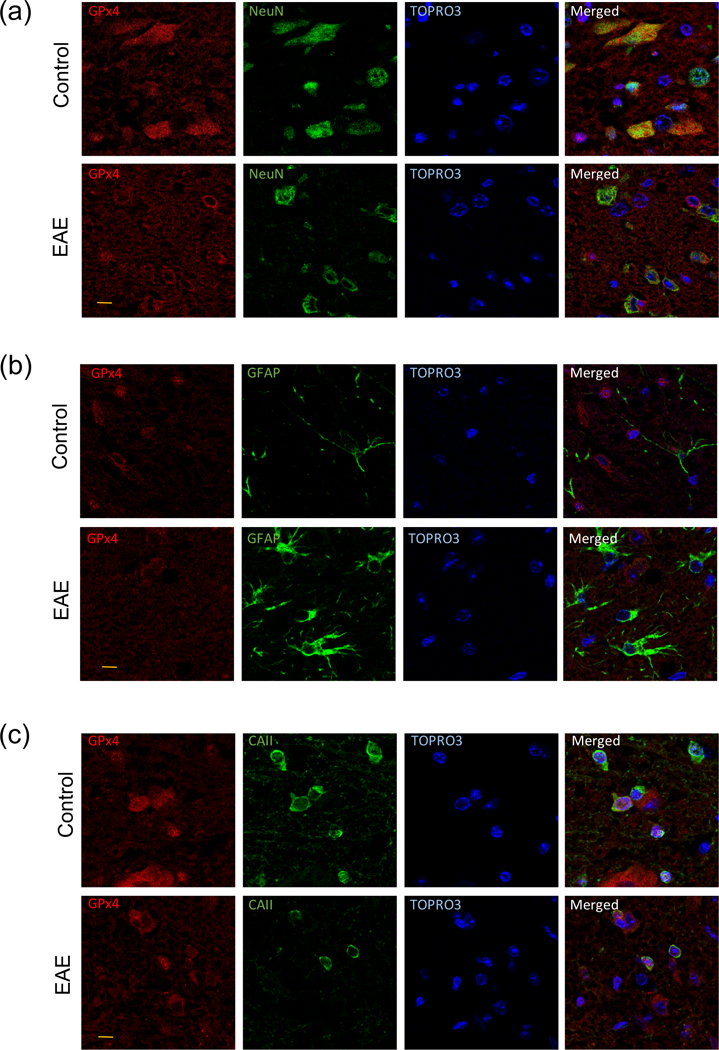

To assess cellular distribution of GPx4 in the lumbar spinal cord of control and EAE mice, paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections (5µm-thick) mounted to slides were deparaffinized and hydrated in down-grade alcohol series. Antigen retrieval were performed in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) with 0.05% Tween-20 using heat-induced retrieval method. Spinal cord sections were blocked in 4% normal goat serum and then incubated with a rabbit monoclonal anti-GPx4 antibody (1:100, RRID:AB_10973901, ab125066, Abcam) at 4 ˚C overnight. The various cell types were detected using mouse monoclonal antibodies against GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) (1:200, RRID:AB_477010, G3893, Sigma) for astrocytes, CA-II (carbonic anhydrase-II) (1:100, RRID:AB_2070328, sc-166547, Santa Cruz) for oligodendrocytes, NeuN (neuronal nuclear antigen) (1:200, RRID:AB_2298772, MAB377, Millipore Corp.; Billerica, MA) for neurons and Iba1 (1:100, RRID:AB_2224402, ab5076, Abcam) for microglia. GPx4 was visualized with a donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to Cy™3 fluorophore (1:500, RRID:AB_2307443, 711–165-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and neural cells were visualized with a goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor® 488 (1:500, RRID:AB_2534084, A11017, Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA). Cellular nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 iodide (500 nM, T3605, Thermo-Fisher). Stained sections were then mounted in polyvinyl alcohol using 1,4-diazabicyclo-[2.2.2]octane as anti-fading agent. Images were captured with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope system. Relative fluorescence of GPx4 immunoreactivity was quantified with the Leica Application Suite X using the histogram tool. Individual regions of interest were delineated in the green, neural-cell marker-labeled cells (NeuN and CAII) and returning the mean grey values in the red (GPx4) channel. For each animal, a total of 6 CAII-stained images (5–20 labeled cells/field) and 12 NeuN-stained images (5–50 labeled cells/field) selected at random were analyzed. Data for oligodendrocytes, microglia and astrocytes come from both white matter and gray matter. Data for neurons derive for the gray matter and also comprise motor neurons.

Determination of GSH and lipid-peroxidation products

GSH levels were determined using the enzymatic recycling method (Shaik and Mehvar 2006). Briefly, proteins from spinal cord homogenates made in the absence of dithiothreitol were precipitated with 1% sulfosalicylic acid and removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15min. Aliquots of the supernatant were then incubated with 0.4 units/ml glutathione reductase, 0.2 mM NADPH, and 0.2 mM 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in 1 ml of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5 containing 5 mM EDTA. The rate of appearance of the thionitrobenzoate anion was measured spectrophotometrically at 412 nm. [GSH] was calculated by interpolation on a curve made with increasing concentrations of GSSG.

The concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) plus 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) was measured with N-methyl-2-phenylindole (Gérard-Monnier et al. 1989). Briefly, aliquots from the spinal cord homogenates (200 µl) were mixed with 800 µl of 4 mM N-methyl-2-phenylindole and 2.2 M methanesulfonic acid in acetonitrile:methanol (3:1 v/v), and were incubated for 40 min at 45°C. Aggregated material was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 586 nm. The amount of MDA plus 4-HNE was calculated using a standard curve prepared with increasing amounts of MDA.

Fatty acid analysis by gas-liquid chromatography

Non-myelin fractions were prepared by ultracentrifugation (82,000 g for 1 h) of spinal cord homogenates, made in 0.25 M sucrose, through a 0.9 M sucrose layer. The pellets were extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1, v/v) containing 1mg/ml of butylated hydroxytoluene. Extracts were rinsed with water, dried under a stream of nitrogen gas, and fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were prepared by alkaline methanolysis. Briefly, lipids were incubated overnight at room temperature in sealed tubes with 1.5 ml of chloroform: 0.2 N NaOH in methanol (2:1, v/v). The solution was then neutralized with 0.2 vol. of 0.35 M acetic acid and rinsed twice with methanol:water (1:1, v/v). The resultant FAMEs were dried under nitrogen, dissolved in hexane and analyzed by gas-liquid chromatography using a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II Gas Chromatograph (Kennett Square, PA) equipped with a fused silica Megabore DB-225 column (15 m x 0.53 mm; J&W, Folsom, CA), a flame ionization detector and an integrator. Peaks were identified by the use of standard FAMEs. The area under each peak was considered proportional to the mass of each FAME within the sample. Membrane peroxidizability index (PI) was calculated according to the following formula: PI = (% monoenoic acids x 0.025) + (% dienoic acids x 1) + (% trienoic acids x 2) + (% tetraenoic acids x 4) + (pentaenoic acids x 6) + (hexaenoic acid x 8) (Pamplona et al. 1998).

Mitochondria structure by TEM

Lumbar spinal cord sections were fixed overnight in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 3% formaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde. Sections were then treated with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h, dehydrated through ethanol and acetone, and embedded in Epon-Araldite resin. Tissue was thin-sectioned and slices on the grids were stained with saturated, aqueous uranyl acetate followed by Reynold’s lead citrate. Finally, mounted sections were examined in a Hitachi HT7700 transmission electron microscope equipped with an AMT XR16M 16-megapixel digital camera.

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed for statistical significance with the unpaired Student’s t-test utilizing GraphPad Prism® program (GraphPad Software Inc.; San Diego, CA) after assessing the normality of the data with the Shapiro-Wilk test. No outliers were identified in any of the data sets using the GraphPad Prism® ROUT test and assigning a Q value of 0.5%.

Results

GPx4 mRNA levels are decreased in the brain of MS patients

The age of the control and MS patients at the time of death, gender, post-mortem interval (PMI) and the pathological diagnosis are shown in Table S.1 and S.2. Ages of control and MS patients range from 53 to 92 years and from 38 to 82 years, respectively. The control group (n= 24) has 16 males/8 females and the MS group (n= 21) has 9 males/12 females. This number of patients (24 control and 21 MS) was above the minimum of 20 patients per group predetermined by power analysis using the G*Power program and considering the following parameters: two-tail analysis, effective size= 0.93, α = 0.05 and a power (1-β) = 0.8. The effective size was calculated assuming a difference between means of 25% and a SD= 27%, which was taken from comparable RNA studies on human samples. PMIs are variable, 4h-20h (14.5 ± 0.9, mean ± SEM) for controls and 6h-29h (14.9 ± 1.3) for MS patients. Within each group (i.e. controls and MS) there is no discernible correlation between the GPx4 mRNA levels and either age (Fig. S.1), gender (Fig. S.2) or PMI (Fig. S.3). Thus, the average values in the control and MS specimens are directly compared without segregation in subcategories.

GM specimens taken from the parietal region (Brodmann area 7) of MS and control brains were used to determine the relative mRNA levels of the three GPx4 isoforms by qPCR. We took special care to ensure that the selected MS specimens were devoid of visible plaques. However, the presence of microscopic lesions in these samples cannot be excluded. Parietal GM was selected for this study because we have previously shown that there is considerable oxidative stress in this area of the MS brains (Bizzozero et al. 2005). Total, mitochondrial and nuclear GPx4 mRNA levels relative to those of GAPDH were measured using the primers shown in Table 1. Relative c-GPx4 mRNA levels were calculated by subtracting 2-ΔCt values of the mitochondrial and nuclear isoforms from those in the total. As shown in Fig. 2, mRNA expression of all three GPx4 isoforms is reduced in MS, although the values corresponding to the cytoplasmic isoform are borderline significant. Relative mRNA levels corresponding to cytoplasmic, mitochondrial and nuclear GPx4 decline in MS by 19.4 ± 3.3 % (p= 0.0568), 30.2 ± 6.1 % (p= 0.0095) and 34.6 ± 7.2 % (p= 0.0483), respectively. However, measurement of GPx4 proteins levels by western blot analysis produced inconclusive results, likely because of the high biological variability of the samples and the semi-quantitative nature of the assay. Due to these issues and because it can be argued that reduced GPx4 mRNA levels in MS may be related to diet/life style, genetics and/or pharmacological treatment rather than to the disease itself, we decided to investigate whether GPx4 mRNA and protein expression is diminished in the CNS of EAE mice.

Fig. 2-.

Diminished GPx4 mRNA expression in MS. c-GPx4 (a), m-GPx4 (b) and n-GPx4 (c) mRNA levels in the gray matter of control (n= 24) and MS patients (n= 21) were determined by qPCR using the primers shown in Table 1 and are expressed relative to those of GAPDH as described in “Materials and Methods”. Each point represents one patient and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test.

Levels of GPx4 mRNA and protein are reduced in EAE

EAE in female C57BL/6 mice was induced by active immunization with MOG35–55 peptide as described under “Materials and Methods” and shown in Fig. 1. Symptoms were graded according to the following scale: 0, no symptoms; 1, tail weakness; 1.5, clumsy gait; 2, hind limb paresis; 2.5, partial hind limb dragging; 3, hind limb paralysis; 3.5, hind limb paralysis with fore limb paresis; 4, complete paralysis; and 5, moribund. In this EAE model, neurological symptoms as well as spinal cord pathology begin at 14 dpi (7 days after the boost with MOG peptide), reaching a maximum between 21 dpi and 30 dpi (Fig. S.4). CFA-injected animals (i.e. controls) do not exhibit any neurological sign or spinal cord damage. In this study, we used a total of 11 control mice (one animal lost) and 12 EAE mice with an average neurological score of 2.70 ± 0.11 (mean ± SEM). This number of mice was very close to the minimum of 12 animals per group predetermined by power analysis using the following parameters: two-tail analysis, effective size= 1.25, α = 0.05 and a power (1-β) = 0.8. The effective size was calculated assuming a difference between means of 25% and a SD= 0.20, which was taken from similar RNA studies on mouse samples.

As shown in Fig. 3, mRNA expression of all three GPx4 isoforms is reduced in EAE, albeit by different extents. Relative mRNA levels corresponding to cytoplasmic, mitochondrial and nuclear GPx4 in EAE decrease by 26.4 ± 4.6 % (p= 0.0022), 43.0 ± 6.5 % (p = 0.0004) and 52.0 ± 6.6 % (p = 0.0016), respectively. It is noteworthy that, like in the human brain, c-GPx4 mRNA in the mouse spinal cord is the most abundant followed by m-GPx4 and n-GPx4 mRNA. We next investigated by western blot analysis if the amount of GPx4 protein is also diminished in EAE. Because the mitochondrial leader peptide is cleaved off after import into mitochondria, c-GPx4 and m-GPx4 cannot be differentiated on SDS gels. Hence, western blots of total homogenates show a single form that corresponds to both species. n-GPx4, whose molecular mass is 29.2 kDa, was not detected on western blot of total spinal cord proteins due to its very low abundance. As shown in Fig. 4, the relative amount of the 20 kDa band corresponding to c-GPx4 and m-GPx4 declines in EAE by 34.7 ± 5.5 % (p = 0.0045), which is similar to the decrease in mRNA expression of the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial forms (see above).

Fig. 3-.

Gpx4 mRNA levels are also decreased in EAE. c-Gpx4 (a), m-Gpx4 (b) and n-Gpx4 (c) mRNA levels in the spinal cord of control (n= 11) and EAE mice (n= 12) were determined by qPCR using the primers shown in Table 1 and are expressed relative to the geometric mean of 4 reference genes as described in “Materials and Methods”. Each point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test.

Fig. 4-.

Reduced GPx4 protein levels in EAE. GPx4 levels in the spinal cord of control (n= 14) and EAE mice (n= 15) were measured by western blot analysis as described in “Materials and Methods”. (a) GPx4 band intensities on the western blots were divided by those of GAPDH, and values expressed as relative to controls. Each point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. (b) Representative immunoblot from 2 control and 2 EAE spinal cords homogenates showing low amounts of GPx4 in the diseased animals.

GPx4 immunostaining of spinal cord neurons is diminished in EAE

To ascertain whether the decrease in GPx4 levels in EAE takes place in all spinal cord cells or whether it is limited to a particular cell type, we conducted a double-label immunofluorescence confocal microscopy analysis. As shown in Fig. 5, images from control and EAE spinal cords reveal GPx4 staining in the cytoplasm/mitochondria of neurons and in the nuclei of oligodendrocytes, while astrocytes are unlabeled. GPx4 labeling is also absent in microglial cells (Fig. S.5). Quantification of the images shows that neuronal GPx4 labeling in EAE decreases by 34.8 ± 10.0 % (p = 0.0303) (Fig. 6a), which coincides with the reduction in the amount of the c-GPx4 and m-GPx4 observed on western blots (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 6b, the number of NeuN-positive neurons was unaltered in EAE. Interestingly, analysis of the same spinal cord sections revealed the presence of cleaved caspase 3-positive cells in EAE (53.0 ± 4.2 cells/section, mostly oligodendrocytes, inflammatory cells and neurons) as compared to controls (1.0 ± 0.6 cells/section) (data not shown), suggesting that there is neuronal degeneration in this disorder. This agrees with previous reports showing an increased number of TUNEL-positive neurons (Dasgupta et al. 2013) and Fluoro Jade-positive cells (Mannara et al. 2012) in EAE spinal cord. However, it should be noted that cells dying by ferroptosis may not exhibit the classical apoptosis markers, so that the number of dying neurons may be larger than previously thought. In contrast to neurons, GPx4 staining in oligodendrocytes, which is mostly nuclear, does not change in EAE (Fig. 6c). There are, however, significantly fewer oligodendrocytes in EAE than in control spinal cord (Fig. 6d), which explains the reduction in n-GPx4 mRNA (Fig. 3). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that GPx4 deficiency in EAE is restricted to neurons. It is interesting that while n-GPx4 is not detected on western blots, GPx4 staining of oligodendrocyte nuclei is quite intense. This might be due to differential antibody affinity toward n-GPx4 when the protein is attached to PVDF membranes or present in paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue section. Alternatively, GPx4 forms, other than n-GPx4, may be present in the nucleus as well. Indeed, upregulation of total GPx4 in vascular smooth muscle cells by butyrate causes a time-dependent increase in the nuclear localization of this protein and almost complete disappearance from the cytoplasm (Mathew et al., 2014). Moreover, overexpression of c-GPx4 in Gpx4-null mice leads to an accumulation of this protein in mitochondria despite the absence of the mitochondrial signal peptide (Liang et al. 2009). Thus, it appears that the subcellular localization of organelle-specific GPx4 isoforms may change under certain experimental conditions. Unfortunately, specific antibodies against n-GPx4 to determine the levels of this isoform in nuclei are not commercially available at the present time.

Fig. 5-.

Representative double-label immunofluorescence images of lumbar spinal cord sections of control and EAE mice depicting the presence of GPx4 in the cytoplasm/mitochondria of neurons and in the nucleus of oligodendrocytes. Spinal cord sections (5µm thick) from control and EAE mice were co-stained with anti-GPx4 antibody and either anti-NeuN (a), anti-GFAP (b) and anti-CAII antibody (c), and images were visualized by confocal microscopy as described in “Materials and Methods”. Red channel is for GPx4 while green channel is for various cell markers. Nuclei were labeled with TO-PRO-3. Bars at lower left of GPx4-stained images represent 10 µm in length.

Fig. 6-.

The amount of GPx4 within neurons, but not oligodendrocytes, is significantly reduced in EAE spinal cord. Double immunofluorescence confocal analysis to estimate the average GPx4 fluorescence intensity in neurons (a) and oligodendrocytes (c) was performed as described in “Methods and Materials”. Values are expressed relative to controls. Average number of neurons (b) and oligodendrocytes (d) per section in the lumbar spinal cord region of control and EAE mice. Cells were identified using the same markers as indicated above in Fig. 4 and TO-PRO-3 staining. Values are expressed relative to controls. In all panels, each data point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM of the 5 control and 7 EAE mice analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test.

Evidence of GSH dysregulation in EAE

GSH levels in the spinal cord of 9 control and 12 EAE mice were determined by the enzymatic recycling method, which measures free GSH and GSSG. As shown in Fig. 7a, the amount of total GSH in EAE relative to control is reduced by 21.1 ± 3.1% (p = 0.0001), indicating that the CNS of the affected animals is subjected to considerable oxidative stress. As we previously reported (Morales Pantoja et al. 2016), reduced [GSH] is likely caused by an impaired synthesis. Indeed, levels of xCT (the transport system responsible for providing cysteine for GSH synthesis), as measured by western blot analysis and expressed relative to that of the housekeeping enzyme GAPDH, diminish by 34.8 ± 8.9% (p = 0.0178) in the EAE animals (Fig. 7b, d). In addition, the amount of GCLc, the rate-limiting enzyme in GSH biosynthesis, decreases by 27.9 ± 5.6% (p = 0.0114) in EAE (Fig. 7c, d). Together, these data point to a significant dysregulation of GSH metabolism, which likely affects several antioxidant pathways in this disease.

Fig. 7-.

Levels of GSH, xCT and GCLc decline in EAE. (a) GSH levels in control and EAE spinal cords were determined using the enzymatic recycling method described in “Materials and Methods”. Values were divided by the amount of protein and expressed as relative to controls. (b, c) xCT and GCLc band intensities on the western blots were divided by those of GAPDH, and values expressed as relative to controls. In all three panels, each data point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM of the 9 control and 10 EAE mice analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. (d) Representative immunoblot from 2 control and 2 EAE spinal cords homogenates showing low amounts of xCT and GCLc in the diseased animals.

Evidence of lipid peroxidation in EAE

The combined amount of the lipid peroxidation products MDA and 4-HNE in the spinal cord of 4 control and 7 EAE mice was measured using N-methyl-2-phenylindole. As shown in Fig. 8a, the levels of MDA + 4-HNE in EAE relative to controls augments by 60.0 ± 9.0% (p = 0.0014), indicating that fatty acid hydroperoxides (the precursors of both MDA and 4-HNE) are formed at a higher rate than they are reduced to hydroxy fatty acids by GPx4. We then investigated if the amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids, the precursor of fatty acid hydroperoxides, is reduced in EAE spinal cords. A non-myelin fraction was used for these experiments to avoid the interference of variable amounts of myelin lipids in the spinal cord homogenates. Fatty acid analysis by gas-liquid chromatography of non-myelin phospholipids in EAE reveals a significant fall in the level of docosahexaenoic acid (22:6 n-3) relative to control (Table S.3 and S.4), which significantly reduces (p = 0.0050) the PI from 219.3 ± 2.5 in control to 209.0 ± 1.5 in EAE (Fig. 8b). Overall, these data demonstrate the occurrence of significant lipid peroxidation in the diseased spinal cord.

Fig. 8-.

Increased lipid peroxidation and reduced membrane peroxidizability index in EAE. (a) Levels of MDA + 4-HNE in control and EAE spinal cord were determined spectrophotometrically as described in “Materials and Methods”. Values were divided by the amount of protein and expressed as relative to controls. (b) Membrane peroxidizability index was calculated from the fatty acid composition of phospholipids in the non-myelin fraction determined by GLC and shown in Tables S.4 and S.5. In both panels, each data point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM of the 4 control and 7 EAE mice analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test.

EAE mitochondria show damages consistent with ferroptosis

Finally, we investigated whether mitochondria in EAE spinal cords show signs of ferroptosis (irregular matrix, disrupted outer membrane and reduced/absent cristae). To this end, lumbar spinal cord sections from 3 control and 4 EAE mice (21 dpi, clinical score: 2.75 ± 0.14) were analyzed by TEM. As shown in Fig. 9a, the percentage of damaged mitochondria, defined as those having at least one of the three above mentioned morphological abnormalities, in EAE augments by 83.3 ± 10.4 % (p = 0.0065) relative to controls. The proportion of mitochondria with an irregular matrix, including the presence of a central or peripheral void, in EAE increases by 270 ± 6 % (p<0.0001) of control values (panel b). The mean proportion of mitochondria with disrupted outer membranes in EAE is 60% higher than that in controls, although this change was borderline significant (p = 0.0577) (panel c). We also observed a significant increase of 98.5 ± 4.9 % (p = 0.0486) in the proportion of mitochondria showing degenerated cristae in EAE compared to controls (panel d). Altogether, these findings suggest that EAE neuronal mitochondria have the characteristic morphological features of ferroptosis.

Fig. 9-.

Mitochondrial damage in EAE is characteristic of ferroptosis. Mitochondria morphology was measured in control and EAE lumbar spinal cord by TEM as described in “Materials and Methods”. Between 94 and 173 intra-axonal mitochondria, derived from 27 images of the lateral columns, were analyzed for signs of (a) overall damage, (b) irregular matrix, (c) disrupted outer membrane and (d) degenerated cristae. In all panels, each data point represents one animal and horizontal bars show the mean ± SEM of the 3 control and 4 EAE mice analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test. (e) Electron micrograph of a normal mitochondrion showing organized cristae and membrane integrity. (f, g) Electron micrographs of damaged mitochondria depicting loss of cristae, irregular matrix with large voids (closed arrows), and membrane rupture (open arrow).

Discussion

Ferroptosis is a newly discovered form of cell death in which the iron-dependent build-up of lipid hydroperoxides (particularly in mitochondria) reaches lethal levels. GPx4, the only enzyme capable of converting toxic lipid hydroperoxides to non-toxic lipid alcohols, is central to the prevention of ferroptotic damage. In this study, we show that mRNA levels corresponding to the three GPx4 forms are reduced both in MS brain and in EAE spinal cord. While data on GPx4 protein levels in MS are inconclusive, we have already shown both reduced GSH levels and increased lipid peroxidation in MS GM (Bizzozero et al. 2005) and others have discovered structural changes in neuronal MS mitochondria such as disappearance of cristae and outer membrane damage (Mahad et al. 2009). Thus, several biochemical/morphological markers of ferroptosis are present in MS. In EAE, western blot analysis of spinal cord proteins clearly reveals that the amount of this enzyme is less than normal. Because the decline in GPx4 protein and mRNA in EAE are similar, it is fair to conclude that reduced enzyme levels are the result of impaired mRNA expression. The reason(s) for the reduction in GPx4 mRNA levels in EAE is unknown but a number of transcriptional activators have been recently described, including Nrf2 (Hirotsu et al. 2012), stimulating protein 1, nuclear factor Y and members of the SMAD family (Ufer et al. 2003), and their expression might be low in this disorder. While there is no data regarding the levels of the last three factors in EAE, Nrf2 expression seems to be reduced in spinal cords of the diseased animals (Morales Pantoja et al. 2016; Souza et al. 2017). This perhaps explains why the Nrf2 targets and negative modulators of ferroptosis, xCT and GCL, are also diminished in EAE (this study; Morales Pantoja et al. 2016). These two enzymes are critical for maintaining normal levels of GSH which, along with GPx4, effectively reduce toxic hydroperoxides. However, the 35% decrease in GPx4 levels in EAE is likely to be more biologically significant than the 20% reduction in GSH levels. This is because under physiological conditions, where the concentration of GSH (2–10mM) is much higher than that of peroxides (nM-µM range), the enzyme is mostly in its ground state waiting for a hydroperoxide to be reduced (Toppo et al. 2009). In this situation, the ability of the enzyme to reduce hydroperoxides will not be affected until [GSH] drops to less than 0.1mM (Toppo et al. 2009). Supporting this idea is the observation that lipid peroxidation products do not accumulate in the spinal cord of mice with a deletion of the modulatory subunit of GCL, despite the fact that the GSH concentration declines by 50% (Zheng and Bizzozero, unpublished results).

Herein, we also show that there is an accumulation of the lipid peroxidation products MDA and 4-HNE in EAE spinal cord that is accompanied by a decrease in the membrane peroxidizability index. Results from a recent lipidomic study in cultured fibroblasts suggest that phosphatidylethanolamines containing arachidonic acid (C20:4, n-6) and adrenic acid (22:4, n-6) are the major phospholipids that undergo oxidation and drive cells to ferroptosis (Kagan et al. 2017). In our study, however, the decrease in the PI of the non-myelin fraction, which contains synaptosomes, mitochondria and microsomal membranes, is due exclusively to a reduction of docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6, n-3). This difference may be explained by the fact that the proportion of docosahexaenoic acid in fibroblast membrane lipids (~0.7%) (Mahadik et al. 1996) is much lower than that in non-myelin lipids (~20%) (Table S.4). We have recently shown that induction of ferroptosis in rat brain slices by acute and complete GSH depletion leads to a decrease in the proportion of all three arachidonic, adrenic and docosahexaenoic acids in mitochondrial phospholipids, suggesting that lipid peroxidation is not limited to a particular type of PUFA during ferroptotic damage of nerve cells (Zheng et al. 2018). Moreover, we have found that in the more severe myelin basic protein-induced EAE model in Lewis rats, the concentration of these three unsaturated fatty acids plus that of the less abundant docosapentaenoic acid (C22:5, n-3) are decreased in the spinal cord at the peak of the clinical disease (Smerjac and Bizzozero, unpublished results).

In this study, we found that not all the spinal cord cells express GPx4. Indeed, GPx4 immunostaining is restricted to the cytoplasm/mitochondria of neurons and the nuclei of CAII-positive oligodendrocytes, while astrocytes and microglial cells are not labeled. The presence of GPx4 in neurons but not astrocytes has been previously reported in adult rat brain (Savaskan et al. 2007). However, that study also showed that Gpx4 is highly expressed in reactive astrocytes following brain injury, which we have not seen in EAE despite significant astrocyte activation. We also found that neurons are the only cells in the spinal cord where GPx4 expression is reduced in EAE. In agreement with this observation, we present evidence that neuronal mitochondria in EAE mice have all the morphological features that are characteristic of ferroptotic damage. Abnormal mitochondrial morphology in EAE and MS has been reported previously and has been linked to pathological permeability transition pore opening mediated by reactive oxygen species and calcium dysregulation (Su et al. 2013). In this regard, it would be interesting to determine whether those reactive oxygen species are lipid hydroperoxides or whether mitochondria are damaged by lipid hydroperoxide accumulation by a different mechanism.

A major difference between ferroptosis and other types of cell death, like apoptosis and necroptosis, is that it can be prevented with iron chelators, lipid peroxidation inhibitors or by increasing GPx4 levels/activity. With regard to the former, MS and EAE are characterized by dysregulation of transition metals like iron (Zarruk et al. 2015) and copper (Melo et al. 2003), which promote oxidative damage via the Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions (Lewen et al. 2000). Moreover, chelation of the pro-oxidant iron with deferoxamine (Pedchenko and LeVine 1998), apoferritin (LeVine et al. 2002) and deferiprone (Mitchell et al. 2007), and copper with N-acetylcysteine amide (Offen et al. 2004) are known to reduce tissue damage and improve the clinical course of EAE. With respect to inhibition of lipid peroxidation, a number of lipophilic antioxidants, including caffeic acid phenetyl ester (Ilhan et al. 2004), butylated hydroxyanisole (Hansen et al. 1995) and tirilazad (Karlik et al. 1996), have been found effective at preventing EAE. In addition, therapeutic success in the treatment of EAE has been reported with α-lipoic acid (Marracci et al. 2002) and mitochondria-targeted ubiquinol (Mao et al. 2013), which are critical for maintaining high levels of reduced vitamin E (α-tocopherol / tocotrienols), a natural scavenger of lipid peroxyl radicals. Finally, while agents that increase GPx4 activity have not been developed, the administration of the GPx-mimetic diphenyl diselenide greatly reduces the development of EAE (Chanaday et al. 2011). All of these studies provide additional support to the notion that ferroptosis takes place in EAE, although it is important to recognize that some of these treatments might be ameliorating this condition by also reducing inflammation.

Ferroptosis has been shown to occur in a number of CNS disorders including Parkinson’s disease (Guiney et al. 2017), Alzheimer’s disease (Hambright et al. 2017) and hemorrhagic stroke (Zille et al. 2017). Our present data showing that expression of GPx4 is reduced in EAE, along with characteristic changes in mitochondrial morphology, decreased [GSH] and proteins involved in GSH synthesis and increased peroxidation of phospholipids, is consistent with the occurrence of ferroptotic damage in inflammatory demyelinating disorders as well. Despite being primarily demyelinating disorders, both MS and MOG35–55 peptide-induced EAE CNS tissues exhibit substantial neurodegeneration. The observation that the ferroptosis inhibitor GPx4 is deficient specifically in neurons may be the cause for neuronal damage in these disorders. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that while oligodendrocytes are injured by a number of inflammatory mediators, neurons are also being damaged by ferroptosis. If this turns out to be the case, the present work could form the basis for the development of a new treatment modality for MS using ferroptosis inhibitors or Gpx4 inducers/activators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Post-mortem brain samples from control and MS patients were kindly provided by the Rocky Mountain MS Center Tissue Bank (Englewood, CO), which is partially supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), and by the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Center (Los Angeles, CA), which is sponsored by NINDS/NIMH, the NMSS and the Department of Veteran Affairs. This work was supported in part by PHHS grants NS084042 and IMSD GM060201 from the National Institutes of Health, and by a research grant (4994-A4) from the NMSS.

Abbreviations:

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GCLc

γ-glutamylcysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- GM

cerebral gray matter

- GPx4

glutathione peroxidase-4

- GSH

glutathione

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PI

peroxidizability index

- PMI

post-mortem interval

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RRID

research resource identifier

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- xCT

cystine-glutamate antiporter

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bizzozero OA (2009) Protein carbonylation in neurodegenerative and demyelinating CNS diseases. In “Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology“ (Lajtha A, Banik N and Ray S, Eds) Springer, New York, NY: pp. 543–562. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzozero OA, DeJesus G, Callahan K and Pastuszyn A (2005) Elevated protein carbonylation in the brain white matter and gray matter of patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Res 81, 687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschan C, Borchert A, Ufer C, Thiele BJ and Kuhn H (2002) Discovery of a functional retrotransposon of the murine phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase: chromosomal localization and tissue-specific expression pattern. Genomics 79, 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso BR, Hare DJ, Bush AI and Roberts BR (2017) Glutathione peroxidase 4: a new player in neurodegeneration? Mol. Psychiatry 22, 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanaday NL, deBem AF and Roth GA (2011) Effect of diphenyl diselenide on the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neurochem. Int 59, 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta A, Zheng J, Perrone-Bizzozero N and Bizzozero OA (2013) Increased carbonylation, protein aggregation and apoptosis in the spinal cord of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. ASN Neuro 5(2): 10.1042/AN20120088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht M, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B and Stockwell BR (2012) Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard-Monnier D, Erdelmeier I, Régnard K and Chaudiére J (1989) Reactions of 1-methyl-2-phenylindole with malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxyalkenals. Chem. Res. Toxicol 11, 1176–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilgun-Sherki Y, Melamed E and Offen D (2004) The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: the need for effective antioxidant therapy. J. Neurol 251, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold R, Hartung HP and Toyka KV (2000) Animal models for autoimmune demyelinating disorders of the nervous system. Mol. Med. Today 6, 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiney SJ, Adlard PA, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI and Ayton S (2017) Ferroptosis and cell death mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Int 104, 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambright WS, Fonseca RS, Chen L, Na R and Ran Q (2017) Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol 12, 8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LA, Willenborg DO and Cowden WB (1995) Suppression of hyperacute and passively transferred experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by the anti-oxidant, butylated hydroxyanisole. J. Neuroimmunol 62, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu Y, Katsouka F, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Nishida Y, Nakayama K, Engel JD and Yamamoto M (2012) Nrf2-MafG heterodimers contribute globally to antioxidant and metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res 40, 10228–10239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilhan A, Akylol O, Gurel A, Armutcu F, Iraz M and Oztas E (2004) Protective effects of caffeic acid phenetyl ester against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis-induced oxidative stress in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med 37, 386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H and Nakagawa Y (2003) Biological significance of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx, GPx4) in mammalian cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med 34, 145–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Friedman Angeli J.P., Doll S, StCroix C, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyruin VA, Ritov VB, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, et al. (2017) Oxidized arachidonic/adrenic phosphatidylethanolamines navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol 13, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlik SJ, Stavraky RT and Hall ED (1996) Comparison of tirilazad mesylate (U-74006F) and methylprednisolone sodium succinate treatments in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in the guinea pig. Mult. Scler 1, 228–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelner MJ and Montoya MA (1998) Structural organization of the human selenium-dependent phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase gene (GPx4): chromosomal localization to 19p13.3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 249, 53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornek B and Lassmann H (1999) Axonal pathology in multiple sclerosis: a historical note. Brain Pathol 9, 651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine SM, Maiti S, Emerson MR and Pedchenko TV (2002) Apoferritin attenuates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL mice. Dev. Neurosci 24, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewen A, Matz P and Chan PH (2000) Free radical pathways in CNS injury. J. Neurotrauma 17, 871–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Yoo S-E, Na R, Walter CA, Richardson A and Ran Q (2009) Short form glutathione peroxidase 4 is the essential isoform required for survival and somatic mitochondrial functions. J. Biol. Chem 284, 30836–30844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti CF, Bruck W, Rodriguez M and Lassmann H (1996) Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicate heterogeneity in pathogenesis. Brain Pathol 6, 259–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad DJ, Ziabreva I, Campbell G, Lax N, White K, Hanson PS, Lassmann H and Turnbull DM (2009) Mitochondrial changes within axons in multiple sclerosis. Brain 132, 1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadik SP, Nukherjee S, Horrobin DF, Jenkins K, Correnti EE and Scheffer RE (1996) Plasma membrane phospholipid fatty acid composition of cultured skin fibroblasts from schizophrenic patients: comparison with bipolar patients and normal subjects. Psychiatric Res 63, 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannara F, Valente T, Saura J, Graus F, Saiz A and Moreno B (2012) Passive experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inV57BL/6 with MOG: Evidence of involvement of B cells. PLoS ONE 7(12): e52361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao P, Mabczak M, Shirendeb UP and Reddy PH (2013) MitoQ, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, delays disease progression and alleviates pathogenesis in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832, 2322–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marracci GH, Jones RE, McKeon GP and Bourdette DN (2002) Alpha-lipoic acid inhibits T cell migration into the spinal cord and suppresses and treats experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol 131, 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew OP, Ranganna K and Milton SG (2014) Involvement of the antioxidant effect and anti-inflammatory response by butyrate-inhibited vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Pharmaceuticals 7, 1008–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo TM, Larsen C, White LR, Aasly J, Sjobakk TE, Flaten TP, Sonnewald U and Syversen T (2003) Manganese, copper, and zinc in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with multiple sclerosis. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res 93, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KM, Dotson AL, Cool KM, Chakrabarty A, Benedict SH and LeVine SM (2007) Deferiprone, an orally deliverable iron chelator, ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mult. Scler 13, 1118–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales Pantoja I.E., Hu CL, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Zheng J and Bizzozero OA (2016) Nrf2-dysregulation correlates with reduced synthesis and low glutathione levels in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem 139, 640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K, Imai H, Koumura T, Kobayashi T and Nakagawa Y (2000) Mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase inhibits the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria by suppressing the peroxidation of cardiolipin in hypoglycaemia-induced apoptosis. Biochem. J 351, 183–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offen D, Gilgun-Sherki Y, Barhum Y, Benhar M, Grinberg L, Reich R, Melamed E and Atlas D (2004) A low molecular weight copper chelator crosses the blood-brain barrier and attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem 89, 1241–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamplona R, Portero-Otin M, Riba D, Ruiz C, Prat J, Bellmunt MJ and Barja G (1998) Mitochondrial membrane peroxidizability index is inversely related to maximum life span in mammals. J. Lipid Res 39, 1989–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedchenko TV and LeVine SM (1998) Desferrioxamine suppresses experimental allergic encephalomyelitis induced by MBP in SJL mice. J. Neuroimmunol 84, 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Lewin AS, Sun L, Hauswirth WW and Guy J (2006) Mitochondrial protein nitration primes neurodegeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Biol. Chem 281, 31950–31962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan N, Borchert A, Bräuer AU and Kuhn H (2007) Role for glutathione peroxidase-4 in brain development and neuronal apoptosis: specific induction of enzyme expression in reactive astrocytes following brain injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med 43, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler A, Schneider M, Forster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Rådmark O, Wurst W, Bornkamm GW, Schweizer U and Conrad M (2008) Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab 8, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik IH and Mehvar R (2006) Rapid determination of reduced and oxidized glutathione levels using a new thiol-masking reagent and the enzymatic recycling method: application to the rat liver and bile samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 385, 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerjac S and Bizzozero OA (2008) Cytoskeletal protein carbonylation and degradation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurochem 105, 763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K (1999) Demyelination: the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Brain Pathol 9, 69–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza PS, Goncalves ED, Pedroso GS, Farias HR, Junqueira SC, Marcon R, Tuon T, Cola M, Silveira PCL, Santos AR, Calixto JB, Souza CT, dePinho RA and Dutra RC (2017) Physical exercise attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting peripheral immune response and blood-brain barrier disruption. Mol. Neurobiol 54, 4723–4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su K, Bourdette D and Forte M (2013) Mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Front. Physiol 4: 169 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JP, Maiorino M, Ursini F and Girotti AW (1990) Protective action of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase against membrane-damaging lipid peroxidation. In situ reduction of phospholipid and cholesterol hydroperoxides. J. Biol. Chem 265, 454–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppo S, Flohé L, Ursini F, Vanin S and Maiorino M (2009) Catalytic mechanisms of specificities of glutathione peroxidases: variations of a basic scheme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790, 1486–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ufer C, Borchert A and Kuhn A (2003) Functional characterization of cis- and trans-regulatory elements involved in the expression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 4293–4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, DePreter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, DePaepe A and Speleman F (2002) Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biology 3, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirova O, O’Connor J, Cahill A, Alder H, Butunoi C and Kalman B (1998) Oxidative damage to DNA in plaques of MS brains. Mult. Scler 4, 413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, Kang R and Tang D (2016) Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ 23, 369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SE, Chen L, Na R, Liu Y, Rios C, Van Remmen H, Richardson A and Ran Q (2012) Gpx4 ablation in adult mice results in a lethal phenotype accompanied by neuronal loss in brain. Free Radic. Biol. Med 52, 1820–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarruk JG, Berard JL, DosSantos RP, Kroner A, Lee J, Arosio P and David S (2015) Expression of iron homeostasis proteins in the spinal cord in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and their implication for iron accumulation. Neurobiol. Dis 81, 93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Hu CL, Shanley KL and Bizzozero OA (2018) Mechanism of protein carbonylation in glutathione-depleted rat brain slices. Neurochem. Res 43, 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zille M, Karuppagounder SS, Chen Y, Gough PJ, Bertin J, Finger J, Milner TA, Jonas EA and Ratan RR (2017) Neuronal death after hemorrhagic stroke in vitro and in vivo shares features of ferroptosis and necroptosis. Stroke 48, 1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.