Abstract

For a three dimensional structure to spontaneously self-assemble from many identical components it must be kinetically accessible. Many icosahedral virus capsids can spontaneously assemble from hundreds of identical proteins, but how they navigate the assembly process is poorly understood. Capsid assembly is thought to involve stepwise addition of subunits to a growing capsid fragment. Course-grained models suggest that the reaction occurs on a downhill energy landscape, so intermediates are expected to be fleeting. In this work, charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS) has been used to track assembly of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) capsid in real time. The icosahedral T=4 capsid of HBV is assembled from 120 capsid protein dimers. The results indicate that there are multiple pathways for assembly. A facile pathway occurs on a mainly downhill energy landscape with no large intermediates. This pathway dominates under the lower salt conditions examined here. Under higher salt conditions, where subunit interactions are strengthened, around half of the products of the initial assembly reaction have masses close to the T=4 capsid, and the other half are stalled intermediates which emerge abruptly at around 90 dimers. When incubated at room temperature, they gradually shift to higher mass and merge with the capsid peak. The stalled intermediates are not kinetically trapped by the lack of the subunits needed to proceed???. Thus they represent local minima on the energy landscape. They probably result from hole closure, where the growing capsid distorts to close the hole due to the missing capsid proteins. The threshold at around 90 dimers presumably reflects the size where hole closure becomes feasible (i.e., where the energy gained by hole closure overcomes the strain induced by distorting the capsid).

Introduction

The design of molecular components that self-assemble into a specific three dimensional structure such as a cage is a challenging task because the geometry must be encoded into the intermolecular interactions of the components. With recent developments in synthetic biology it is now possible to design proteins that assemble into small cages.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 However, the most exquisite examples of protein cages still come from nature. A virus capsid, the protein shell that surrounds the viral genome, is assembled from many, often hundreds, of identical proteins. For self-assembly to occur, the desired endpoint must be thermodynamically favored and kinetically accessible. In other words, there must be a facile, low energy pathway that leads to the desired structure. While a lot is known about the structures of natural protein cages. Much less is known about how they assemble and avoid undesirable outcomes.

A spherical cage structure can, in theory, be generated with any number of components.9,10 However, spherical virus capsids are invariably icosahedral and exist in only a few discrete sizes. The sizes are described by a triangulation number (T), where 60T is the number of proteins in the capsid.11 Symmetry dictates that only certain T numbers are allowed; the smallest ones are 1, 3, 4, and 7, and they contain 60, 180, 240, and 420 capsid proteins, respectively.

Capsid assembly is thought to involve three steps: formation of a nucleus (a small capsid fragment), the sequential addition of capsid building blocks to the growing capsid; and finally closure, where the final building block is inserted to complete the icosahedron.12,13,14,15,16 The building block can be a capsid protein, a dimer, or a larger capsid fragment. Course grained models suggest that the energy landscape for subunit addition to the nucleus is uniformly downhill,16 except perhaps for the completion step.14 Thus during the assembly reaction, capsid building blocks and fully formed capsids are expected to be dominant over low abundance intermediates.17

In the work reported here we have used charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS)18,19 to track the assembly of the icosahedral T=4 capsid of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in real time. Infectious HBV virus capsids are formed through the assembly of the wild type 183-residue capsid protein (Cp183). A truncated form of the capsid protein which lacks the C-terminal nucleic acid binding domain (Cp149) also assembles into icosahedral capsids.20 The dimer is thought to be the building block, and the capsid is believed to assemble by sequential addition of Cp149 dimers to a nucleus.21 In vitro assembly can be triggered by raising the ionic strength, which strengthens dimer-dimer interactions. However, at high ionic strengths intermediates may become kinetically trapped. This occurs when a large number of nuclei are formed early in the assembly reaction, and there is insufficient dimer present to complete them.

High resolution mass spectrometry (MS) and ion mobility mass spectrometry have been used to investigate early intermediates in HBV capsid assembly as well as intact capsids.22,23,24 Using charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS), we previously identified kinetically trapped, high-mass intermediates in HBV assembly.25 CDMS is a single-particle technique where the mass of each ion is directly determined from simultaneous measurements of its m/z and charge (z). It is particularly well-suited to monitoring the heterogeneous mixture of high-mass intermediates that may result from capsid assembly. In a previous study, the assembly reactions were performed in sodium chloride, and then the products and intermediates were dialyzed into ammonium acetate for analysis (because native electrospray requires a volatile salt). In this work, we perform the assembly reactions in ammonium acetate so that we can avoid the dialysis step and monitor assembly on a much shorter timescale. Some of the CDMS results are corroborated by time resolved small angle x-ray scattering (TR-SAXS). TR-SAXS is an ensemble technique that can provide size and temporal information about assembly intermediates directly in solution.26,27,28

Experimental Methods

Preparation of Capsid Protein Cp149

The truncated form of the capsid protein containing only the assembly domain (Cp149) was expressed in E. coli and purified as previously described.29 A re-assembly and dissociation step was included in the purification procedure to remove inactive protein. Assembly competent protein was dialyzed into 20 mM ammonium acetate at pH 7.5. Assembly was initiated by raising the ammonium acetate concentration to increase the ionic strength.

Time Resolved Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry

In ion trap CDMS, single ions are trapped in a linear ion trap where they oscillate back and forth through a conducting cylinder. As an ion enters the cylinder it induces a charge which is detected by a charge sensitive preamplifier. The resulting signal is analyzed to provide the m/z and charge, which are combined to provide the mass of each ion.

A detailed description of the home-built charge detection mass spectrometer used in this work can be found elsewhere.30,31,32,33,34 Ions are generated by a chip-based nanoelectrospray source. They enter the instrument through a heated capillary and pass through three differentially pumped regions where they are separated from the ambient gas that flows through the capillary. The ions are then accelerated through a 100 V potential difference and focused into an ion beam. A narrow band of ion energies centered on 100 eV/z is selected by a dual hemispherical deflection energy analyzer (HDA) and focused into a modified cone trap that contains the charge detection cylinder. Potentials are applied to the endcap electrodes to trap ions. In this work we used random trapping (where the trap is closed without knowing whether an ion is present) with a trapping period of 100 ms.

As the trapped ion oscillates back and forth through the detection cylinder it induces a periodic signal which is amplified, digitized, and then analyzed in real time by a Fortran program using fast Fourier transforms. The m/z is obtained from the fundamental frequency and the charge is obtained from the magnitudes of the fundamental and first harmonic. The calibration of the charge and m/z measurements has been discussed elsewhere.34 Ions passing through the trap have a narrow distribution of kinetic energy per charge defined by the HDA and therefore each ion’s velocity is related to its m/z, i.e., v ∝ (m/z)−1/2. With random trapping the probability an ion is trapped is proportional to the time it spends in the trap. Consequently, slow (high m/z) ions are trapped more easily than fast (low m/z) ions. To correct for this difference each ion is weighted by its m/z−1/2.

For the time resolved CDMS measurements, a solution of 10, 20, or 40 μM Cp149 dimer in 20 mM ammonium acetate was mixed with an equal volume of 400 or 1,000 mM ammonium acetate solution to initiate assembly. After mixing the reaction mixture was immediately loaded into the reservoir of the nanoelectrospray source, where the assembly reaction continues while the solution is electrosprayed. The ions detected by CDMS are time-stamped, and so knowing when the assembly reaction was initiated it is possible to relate each ion to a particular reaction time. The frequency of single ion trapping events is relatively low, 3–4 ions per second at best, with random trapping and the 100 ms trapping period used here. Too few ions are detected in a single reaction to generate time resolved spectra. To increase the number of ions, the results of many identical reactions were combined and sorted into time windows.

Time Resolved Small Angle X-Ray Scattering

TR-SAXS experiments were performed using a BioLogic SFM-400 stopped-flow device connected to a 1.6 mm quartz capillary. This apparatus was installed at the ID02 Beamline at the ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble, France. In each reaction, 75 μL of ammonium acetate solution were mixed with 150 μL Cp149 solution for a final concentration of 27 μM Cp149 in 163 mM ammonium acetate. Relatively large volumes were used to ensure that each reaction was completely separated from the previous one and that no reaction product remained in the capillary. Mixing took around 35 ms with a flow rate of 6.43 mL/s. The measurements were performed at 25°C. The exposure time of each measurement was 20 ms. To avoid sample damage, no more than 20 exposures were recorded for each reaction. Both capsid solutions and their corresponding buffers were measured through the same spot in the quartz capillary. The scattering intensity curve of the buffer was subtracted from the scattering intensity curve of the corresponding capsid solution.

Results

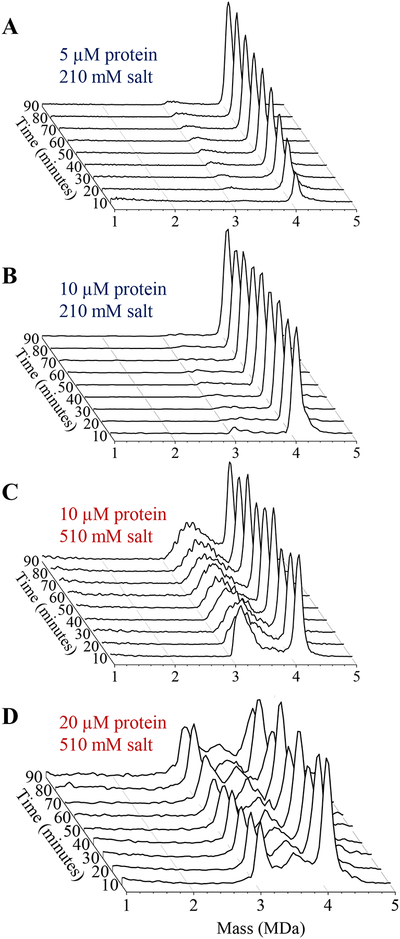

Time resolved CDMS measurements were performed with a variety of ammonium acetate and Cp149 dimer concentrations. Some typical results are shown in Figure 1. The measurements shown in the figure were performed with Cp149 dimer concentrations (after mixing) of 5, 10, and 20 μM and ammonium acetate concentrations of 210 mM and 510 mM.

Figure 1.

Time-resolved CDMS spectra showing the progression of capsid assembly over the first 90 minutes for a reaction mixture containing an initial dimer concentration of (A) 5 μM in 210 mM ammonium acetate (B) 10 μM in 210 mM ammonium acetate (C) 10 μM in 510 mM ammonium acetate and (D) 20 μM in 510 mM ammonium acetate. The earliest time interval (0–10 minutes) is at the front. The spectra were generated using 20 kDa bins.

The results in each panel of Figure 1 are a compilation of the ions measured for a number (8 to 28) of identical experiments. For all the experiments, ions were recorded continuously for at least 90 minutes after the assembly reaction was initiated. Some of the reaction mixtures were also sampled periodically over the course of several days. The x-axis in Figure 1 shows the mass with 20 kDa bins, the y-axis is the intensity normalized by total peak area (including the low mass ions that are not shown in the plot for clarity), and the z-axis represents the reaction time binned into 10 minute intervals. The earliest time interval (0–10 minutes) is at the front of each plot.

Figure 1A shows time-resolved CDMS spectra measured over the first 90 minutes of an assembly reaction with a dimer concentration of 5 μM and an ammonium acetate concentration of 210 mM. The most prominent assembly product in the CDMS spectra is the peak at around 4.1 MDa which is attributed to an overgrown T=4 capsid (i.e., a capsid with slightly more than the expected 120 dimers).35

HBV can form both T=3 and T=4 capsids in vivo and in vitro.36,37 The T=3 capsid contains 90 dimers. In vivo, with wild type Cp183, around 10% of the capsids are T=3. For in vitro assembly with Cp149 the relative abundances are affected by the identity and ionic strength of the assembly buffer.38,39

In ammonium acetate, little if any T=3 capsid is formed under low salt conditions.35

If the assembly reaction is treated as an equilibrium, the capsid concentration is given by:

The large stoichiometry coefficient leads to a pseudo critical concentration for capsid formation. Below the pseudo critical concentration the capsid concentration is very small; free dimer is the main species present. Above the pseudo critical concentration the capsid concentration increases approximately linearly as any dimer above the pseudo critical concentration is mainly converted into capsid. Under the conditions used here the pseudo critical concentration is 3.55 μM. Thus the dimer concentration used to obtain the results in Figure 1A (5 μM) is only slightly above the pseudo critical concentration.

The low dimer concentration coupled with the low salt concentration used to obtain the results in Figure 1A leads to a relatively slow assembly. The peak at 4.1 MDa can be seen to grow in during the 90 minute time window shown. We found that different dimer preparations often led to different rates of assembly. The results shown in Figure 1A are on the slow end for these conditions. A few other species are observed in the 1 to 5 MDa mass range shown in the figure. There is a broad low intensity feature at early times at around 1 MDa and a small feature at around 3.2 MDa. We consider the species observed below 1 MDa below.

Figure 1B shows the result of increasing the dimer concentration to 10 μM under the same low salt conditions used for Figure 1A. With the higher dimer concentration, the initial assembly reaction is much faster and appears to be complete well within the first 10 minute time interval. A small feature at around 3.1 MDa is present in the first time point and shifts to higher mass as the reaction proceeds.

Figure 1C shows the effect of increasing the salt concentration while maintaining the dimer concentration (10 μM) used in Figure 1B. Raising the salt concentration leads to a large increase in the abundances of species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa. According to light scattering measurements, the initial assembly reaction is complete in under a minute for the conditions used here.35 A little over half of the of the products have masses between 3 and 4 MDa while a little under half are in the overgrown capsid peak at around 4.1 MDa. At the first time point in Figure 1C there is a broad feature at around 3.2 MDa with a high mass tail, and a sharper capsid peak at around 4.1 MDa. As the reaction proceeds, the broad peak at around 3.2 MDa becomes broader and moves to higher masses, progressing towards the capsid peak. After 90 minutes, most of the large species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa are still present and there has not been a significant increase in the intensity of the capsid peak.

We have previously used CDMS to detect kinetically trapped intermediates from the assembly of Cp149 in 1 M sodium chloride.25 In that work, the assembly products were dialyzed into 300 mM ammonium acetate for analysis. We observed a broad distribution of species with masses between 3.2 MDa and 4.0 MDa with prominent features at 3.5 and 3.7 MDa. We do not observe the same prominent features here. However, we do observe a similar broad distribution of intermediates with masses between 3 and 4 MDa. Another difference is that the intermediates observed in this work progress over time.

Figure 1D shows time-resolved CDMS spectra measured over the first 90 minutes of an assembly reaction initiated with a Cp149 dimer concentration of 20 μM and an ammonium acetate concentration of 510 mM. Doubling the dimer concentration under high salt conditions has not lead to a significant change in the relative abundance of the capsid peak and species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa. However, the distribution of species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa is different, and unlike the situation with the lower dimer concentration, they are do not appear to progress much with time. There is a peak at around 3.1 MDa accompanied by a broad distribution of species with masses between 3.1 and 4.0 MDa. The peak of this distribution is at around 3.7 MDa.

Another notable feature of the results shown in Figure 1D is the substantial high mass tail that extends from the peak at around 4.1 MDa. A closer inspection of all the results in Figure 1 shows that there are high mass tails on the 4.1 MDa peak under all conditions. The tail in Figure 1D is the most prominent, extending to almost 5 MDa. As noted above, the peak at around 4.1 MDa is at a mass slightly larger than expected for a perfect T=4 capsid, indicating that it is overgrown.

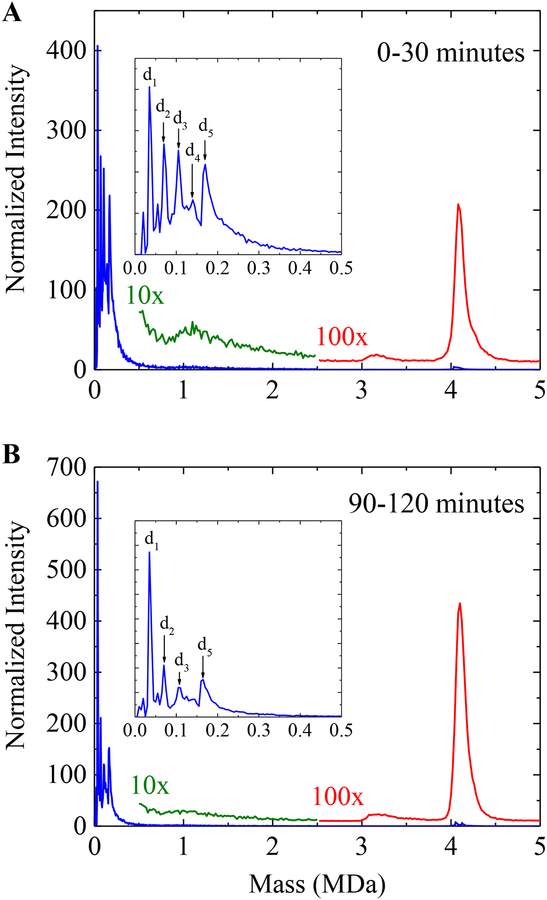

Figure 2A shows a higher resolution CDMS spectrum for the first 30 minutes of the assembly reaction shown in Figure 1A (5 μM dimer in 210 mM ammonium acetate). The spectrum was generated by binning all ions measured in the first 30 minutes into 5 kDa bins. The inset shows an expanded view of the low mass region where peaks due to the dimer and oligomers of up to five dimers are resolved. The oligomers are denoted by dn where n represents the number of dimers present. Beyond (dimer)5 the signal tails off. The green line shows ions with masses between 0.5 and 2.5 MDa binned into 20 kDa bins, enlarged by a factor of 10, and vertically offset. A broad low intensity peak is evident at around 1.1 MDa. The red line shows ions above 2.5 MDa binned into 20 kDa bins, enlarged by a factor of 100, and vertically offset. A small peak at around 3.2 MDa is evident.

Figure 2.

(A) CDMS spectrum for the first 30 minutes and (B) for 90–120 minutes after initiation of the assembly reaction with a dimer concentration of 5 μM in 210 mM ammonium acetate. The blue spectrum was generated with 5 kDa bins. The insets in (A) and (B) show an expanded view of the low mass region up to 0.5 MDa where dimer (d1) and oligomers up to five dimers (d5) are resolved. The overlaid green and red spectra have been scaled up by factors of 10x and 100x, respectively. They were generated with 20 kDa bins.

Figure 2B shows the corresponding spectrum for the 90–120 minute time interval. Peaks are resolved for dimer to (dimer)5 (see inset in Figure 2B). At the later time interval the peaks corresponding to (dimer)2 through (dimer)5 have decreased significantly relative to the free dimer peak. The broad low intensity feature observed at around ~1.1 MDa in the 0–30 minute spectrum has almost disappeared. The fact that this feature diminishes as the reaction proceeds, and the capsid peak grows, suggests that it may be due to intermediates. The prominent peak at around 4.1 MDa has a high mass tail which extends further in spectrum for 0–30 minutes.

The mass of the T=3 capsid is around 3.0 MDa. The small peak at around 3.1 MDa in the 0–30 minute spectrum (Figure 2A), however, does not appear to be due to the T=3 capsid. This peak has broadened slightly and shifted to slightly higher mass in the 90–120 minute spectrum (Figure 2B) and over time it continues to shift to higher mass.

The spectra in Figure 2 are dominated by the peaks due to the dimer and dimer oligomers. The relative abundance of the capsid peak is very low. The low relative abundance results because the initial dimer concentration (5 μM) is only slightly larger than the pseudo critical value (3.55 μM). After 24 hours, the ratio of the number of dimers in the low mass species (<2.5 MDa) in the CDMS spectrum to the number of dimers in the high mass species (>2.5 MDa) is in reasonable agreement with ratio of dimer to capsid determined at the same time point with size exclusion chromatography.35

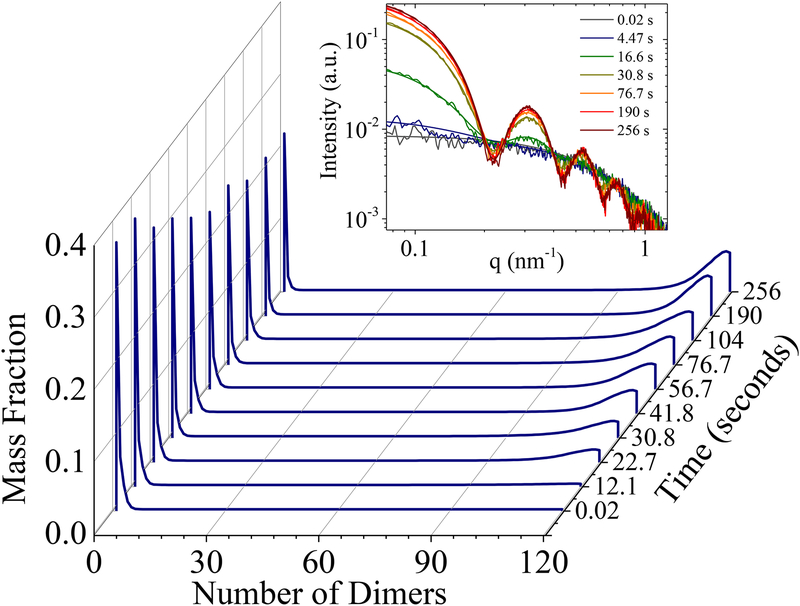

TR-SAXS measurements of Cp149 assembly were performed to compare with the CDMS measurements and to determine if additional intermediates were present on a timescale shorter than several minutes. The assembly conditions in these experiments are similar to those used in the CDMS measurements: a slightly lower ammonium acetate concentration (163 mM versus 210 mM) was employed to partly compensate for the higher dimer concentration needed to optimize the signals in the TR-SAXS experiments (27 μM). The TR-SAXS data were fit to a linear combination of computed SAXS curves of 120 T=4 and 90 T=3 HBV capsid intermediates containing a single hole at the capsid surface. Atomic models were computed based on the Cp149 dimer atomic model taken from the protein data bank (PDB) file 2G33 and docked into the relevant symmetry.40 The raw TR-SAXS data and modeled curves for representative time points from 0.02 s to 256 s are displayed in the inset in Figure 3. The resulting mass fractions of the intermediates that fit the data within the noise level were determined by using the maximum entropy optimization method introduced by Jaynes.41 A detailed description of the method will be provided in a future publication. Figure 3 shows the mass fraction of each of the 120 intermediates modeled to be on pathway to a T=4 capsid. At the earliest time point of 0.02s, only small intermediates up to 5 dimers are present in any significant amount. After 22 seconds, there is an increased abundance of high molecular weight intermediates containing more than 90 dimers. After 256 seconds, only small intermediates (<5 dimers), high molecular weight intermediates (>90 dimers), and T=4 capsids are observed. The estimated mass fraction of the T=3 capsids is less than 1.×10−3 which is negligible. Thus the TR-SAXS results are in general agreement with the longer timescale time-resolved CDMS measurements. Notably, the TR-SAXS measurements do not reveal any intermediates that were not found in the time-resolved CDMS measurements.

Figure 3.

Mass fractions of intermediates with one to 120 dimers detected in the first 256 seconds of capsid assembly by TR-SAXS. The mass fractions are obtained from calculated SAXS curves that model the lowest energy intermediates on pathway to T=4 capsids. The assembly reaction was initiated with a dimer concentration of 27 μM in 163 mM ammonium acetate. The inset shows the raw TR-SAXS data and overlaid modeled curves for representative time points from 0.02 s to 256 s.

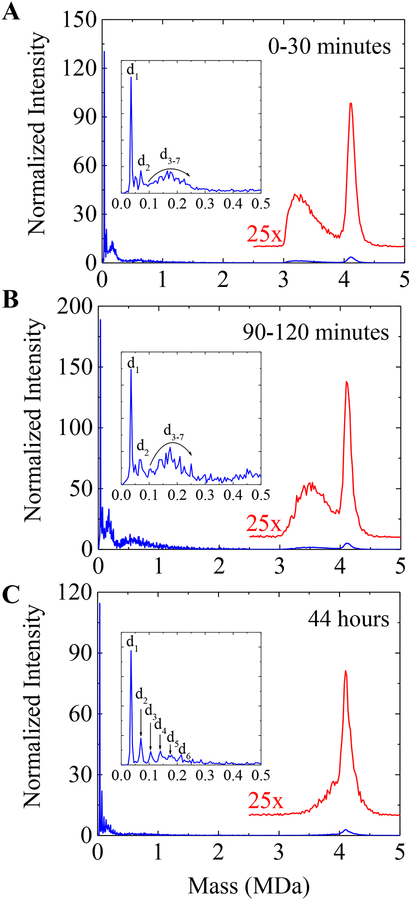

Returning to the CDMS measurements, assembly in 510 mM ammonium acetate generates a much higher abundance of species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa. Figure 4 shows a more detailed view of the species generated with an initial dimer concentration of 10 μM. The mass spectrum represented by the blue trace in Figure 4A was generated by binning all ions from the first 30 minutes of the assembly reaction shown in Figure 1C into 5 kDa bins. The inset shows an expanded view of the low mass region up to 0.5 MDa where peaks due to the dimer and dimer oligomers are resolved. The red trace shows ions with masses between 2.5 and 5 MDa binned into 20 kDa bins, enlarged by a factor of 25, and vertically offset. The inset in Figure 4A shows the most abundant peak in the spectrum corresponds to dimer with a small amount of (dimer)2. A broad distribution of masses out to 0.25 MDa corresponds to dimer oligomers from (dimer)3 to (dimer)7, however the larger oligomers are poorly resolved, partly due to their low abundances. Few species are observed between 1 and 3 MDa. A broad distribution exists between 3 and 4 MDa, with the apex of the distribution centered at around 3.2 MDa. The prominent peak at around 4.1 MDa is close to the mass expected for the T=4 capsid. Figure 4B shows the spectrum for a time interval of 90 to 120 minutes. Above 3 MDa, the broad distribution has shifted to a higher mass, with the apex at around 3.5 MDa now. After 44 hours (Figure 4C) the broad peak between 3 and 4 MDa appears to have merged with the capsid peak at around 4.1 MDa. The capsid peak still has a low-mass tail, suggesting that some capsids are still struggling to complete. The inset in Figure 4C shows that the dimer and dimer oligomers up to (dimer)6 are resolved at this time.

Figure 4.

(A) CDMS spectrum measured for the first 30 minutes, (B) 90–120 minutes, and (C) 44 hours after initiation of an assembly reaction with a dimer concentration of 10 μM in 510 mM ammonium acetate. The blue spectra were generated with 5 kDa bins. The insets in (A), (B) and (C) show an expanded view of the low mass region up to 0.5 MDa where dimer (d1) and dimer oligomers are resolved. The overlaid red spectra were generated with 20 kDa binds and have been scaled up by a factor of 25x.

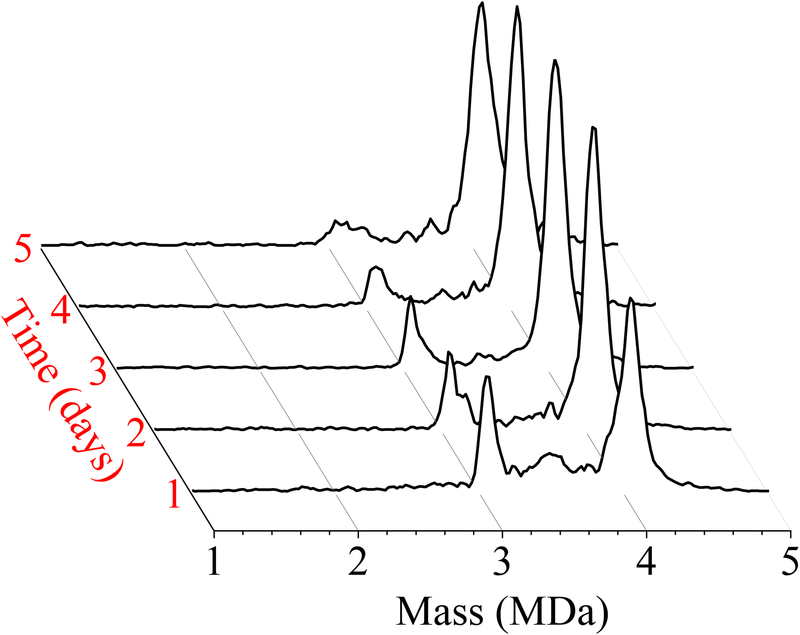

Figure 5 shows CDMS spectra measured over five days for the assembly of 20 μM dimer in 510 mM ammonium acetate; the conditions of this reaction are identical to those used for Figure 1D. The x-axis shows the mass binned into 20 kDa bins, the y-axis is the intensity normalized by peak area, and the z-axis represents the reaction time binned into 1 day intervals. After 1 day there is still a relatively sharp peak at 3.1 MDa (around 90 dimers) along with a broad, lower intensity distribution between 3.2 and 4 MDa. Over the next few days the sharp peak at 3.1 MDa decreases in abundance and appears to shift in mass towards the T=4 capsid. This trend is consistent with the behavior observed for assembly under lower dimer and salt conditions. After five days, there is no longer a discernible peak at 3.1 MDa and the intensity between 3 and 4 MDa has become much lower. These results indicate that the peak at 3.1 MDa is not due to the T=3 capsid. The T=3 capsid is stable in ammonium acetate. T=3 capsids assembled in sodium chloride and dialyzed into ammonium acetate persist in solution for months. Thus the species in Figure 5 with a mass around 3 MDa is not the T=3 capsid.

Figure 5.

Time-resolved CDMS spectra showing the progression of capsid assembly over five days for a reaction mixture containing a total protein (dimer) concentration of 20 μM in 510 mM ammonium acetate. The earliest time interval (1 day) is at the front. The spectra were generated using 20 kDa bins.

Discussion

With the lower salt concentration there is a facile pathway from dimer to capsid, and few intermediates are observed.

The main features in the CDMS spectrum measured for assembly with the lower salt concentration (210 mM) are the dimer, small oligomers, and a relatively narrow peak at around 4.1 MDa attributed to the overgrown capsid.35 For the lower dimer concentration (5 μM) there is also a broad peak centered on around 1.1 MDa (around 32 dimers) (see Figure 2A). This feature is most abundant in the spectrum for the earliest time point (see Figure 1A). It is probably a roughly circular fragment of the T=4 capsid. The small oligomers and the feature at around 1.1 MDa behave like intermediates. They are observed early in the reaction and depleted as the reaction proceeds. The low abundances of species with masses between 2 and 4 MDa indicates that there must be a facile pathway from the dimer and small oligomers to the overgrown capsid with no significant pause points along the way (i.e., the assembly landscape is close to uniformly downhill). The facile pathway probably involves intermediates that are fragments of the complete capsid. The small oligomers are prominent during assembly and so capsid growth could occur through the addition of both dimers and small oligomers.

With the higher salt concentration around half of the assembly products are diverted into low free energy intermediates with masses between 3 and 4 MDa.

When the salt concentration is increased to 510 mM, the initial assembly reaction is complete in less than a minute. However, only around half of the products of the initial assembly reaction are in the peak at around 4.1 MDa due to the overgrown capsid. The balance is intermediates with masses between 3 and 4 MDa. With a dimer concentration of 10 μM, the 3–4 MDa intermediates gradually shift to higher mass during the 90 minutes timescale shown in Figure 1C. Inspection of Figure 4 shows that a significant amount of the dimer remains after the initial assembly reaction is complete. Thus species with masses between 3 and 4 MDa are not trapped by the absence of dimer needed to proceed to capsid, there is plenty of dimer available, so they are not kinetically trapped. Instead, these species must resist proceeding to the complete capsid because they are local free energy minima.

With an initial dimer concentration of 20 μM, the 3–4 MDa intermediates are kinetically trapped.

With a dimer concentration of 20 μM, the 3–4 MDa intermediates do not progress during the 90 minutes shown in Figure 1D. However, the dimer concentration after the initial assembly reaction is much lower than with the 10 μM initial dimer concentration, and difficult to measure. Thus, at the higher dimer concentration the intermediates do not progress during the first 90 minutes because they are kinetically trapped. As shown in Figure 5, they do progress over a much longer timescale.

The stable intermediates that suddenly emerge at around 90 dimers are not T=3 capsids.

A striking feature of the results presented here is the abrupt emergence of intermediates at around 90 dimers (see Figure 1), close to the mass of a T=3 capsid. However, the trapped intermediates slowly progress towards the T=4 capsid, so their emergence at 90 dimers is not related to the T=3 capsid. Assuming that facile pathway for capsid assembly involves intermediates that are fragments of the complete capsid there are two explanations for the emergence of the intermediates at 90 dimers: either there is a subset of the capsid fragments that are more stable and progress more slowly under high salt conditions, or another geometry that can only be accessed with 90 dimers is involved.

The stable intermediates that emerge at around 90 dimers are probably not capsid fragments.

A plausible low energy geometry for an incomplete T=4 capsid missing up to around 30 dimers is a T=4 capsid with a single, roughly-circular hole. There is an energetic cost associated with the hole (the line tension) which results from missing dimer-dimer contacts. The line tension acts to minimize the length of the perimeter of the hole, making a single circular hole favorable to multiple holes and non-circular holes. A high symmetry intermediate with a single hole can be formed by removing a circular 30 dimer fragment from a T=4 capsid. Due to its symmetry, addition of another dimer to this species would be less favorable because it would be bound by only two dimer-dimer contacts. This could provide an explanation for why the 90 dimer species is a prominent intermediate. However, it does not provide an explanation for why progression of all species between 3 and 4 MDa is slow, it does not provide an explanation for why progression is fast below 3 MDa where similar species could be devised, and it does not provide an explanation for why the intermediates become stalled when the ionic strength is increased.

Hole collapse may account for the emergence of stable intermediates at around 90 dimers.

It is known that a hole in a shell can collapse before the optimum number of subunits is present.42 In this case, the energetic cost of distorting the shell to fill the hole is compensated by the loss of line tension. A plausible explanation for the sudden emergence of the trapped intermediates at 90 dimers is that this is the minimum size where it is energetically favorable for the hole to collapse. For a T=4 capsid with a hole of around 30 dimers, distortion from a spherical geometry could allow the hole to heal. This geometry would be lower in energy that the undistorted T=4 fragment, but higher in energy than the complete T=4, so it is still energetically favorable to complete the capsid. However, in order for the capsid to grow, it is now necessary to open-up at least part of the sealed edge of the hole. There is an energetic cost associated with opening-up the hole, leading to an activation energy for capsid growth. This would explain why the intermediates take so long to complete. Also, the reason the intermediates are only observed under high salt conditions is that the high ionic strength strengthens the dimer-dimer interactions so that the energy gained by sealing the hole is larger than the energetic penalty of distorting the capsid.

Conclusions

The results presented here indicate that assembly of the HBV capsid can follow multiple pathways with disparate timescales. There is a facile pathway from dimer to the overgrown capsid. This pathway occurs on an energy landscape that must be almost uniformly downhill. Under the lower salt conditions studied here almost all of the assembly reaction follows this route. The most prominent intermediates are small oligomers and a broad, low-abundance distribution with around 32 dimers. Few intermediates are observed between 2 and 4 MDa.

Under the higher salt conditions studied here the initial assembly reaction is fast, occurring in less than a minute. However, around half of the assembly is stalled at around 90 dimers and then progresses much more slowly towards the capsid. A plausible explanation for the stalled intermediates is that they result from hole closure where the capsid has distorted to close the hole due to the missing dimers. Increasing the salt concentration strengthens dimer-dimer interactions which favors hole closure. The abrupt appearance of the intermediates at around 90 dimers can be attributed to the presence of a minimum size for hole closure.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the NIH through Award Number 1R01AI118933. We thank Narayanan Theyencheri and his team at the ID02 Beamline at the ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble, France.

References

- 1.Yeates TO; Padilla JE Designing Supramolecular Protein Assemblies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2002, 12, 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padilla JE; Colovos C; Yeates TO; Nanohedra: Using Symmetry to Design Self Assembling Protein Cages, Layers, Crystals, and Filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2217–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai YT; Cascio D; Yeates TO Structure of a 16-nm Cage Designed by Using Protein Oligomers. Science 2012, 336, 1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King NP; Sheffler W; Sawaya MR; Vollmar BS; Sumida JP; André I; Gonen T; Yeates TO; Baker D Computational Design of Self-Assembling Protein Nanomaterials with Atomic Level Accuracy. Science 2012, 336, 1171–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai YT; King NP; Yeates TO Principles for Designing Ordered Protein Assemblies. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King N; Bale JB; Sheffler W; McNamara DE; Gonen S; Gonen T; Yeates TO; Baker D Accurate Design of Co-Assembling Multicomponent Protein Nanomaterials. Nature 2014, 510, 103–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai Y-T; Reading E; Hura GL; Tsai K-L; Laganowsky A; Asturias FJ; Tainer JA; Robinson CV; Yeates TO Structure of a Designed Protein Cage that Self-Assembles into a Highly Porous Cube. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 1065–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsia Y; Bale JB; Gonen S; Shi D; Sheffler W; Fong KK; Nattermann U; Xu C; Huang PS; Ravichandran R; Yi S; Davis TN; Gonen T; King NP; Baker D Design of a Hyperstable 60-subunit Protein Icosahedron. Nature 2016, 535, 136–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zandi R; Reguera D; Bruinsma RF; Gelbart WM; Rudnick J Origin of Icosahedral Symmetry in Viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15556–15560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fejer SN; Chakrabarti D; Wales DJ Emergent Complexity from Simple Anisotropic Building Blocks: Shells, Tubes, and Spirals. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspar DLD; Klug A Physical Principles in the Construction of Regular Viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 1962, 27, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endres D; Zlotnick A Model-Based Analysis of Assembly Kinetics for Virus Capsids or Other Spherical Polymers. Biophys. J 2002, 83, 1217–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zandi R; van der Schoot P; Reguera D; Kegel W; Reiss H Classical Nucleation Theory of Virus Capsids. Biophys. J 2006, 90, 1939–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen HD; Reddy VS; Brooks CL Deciphering the Kinetic Mechanism of Spontaneous Self-Assembly of Icosahedral Capsids. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagan MF; Elrad OM Understanding the Concentration Dependence of Viral Capsid Assembly Kinetics - The Origin of the Lag Time and Identifying the Critical Nucleus Size. Biophys. J 2010, 98, 1065–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagan MF Modeling Viral Capsid Assembly. Adv. Chem. Phys 2014, 155, 1–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zlotnick A To Build a Virus Capsid. J. Mol. Biol 1994, 241, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuerstenau SD; Benner WH Molecular Weight Determination of Megadalton DNA Electrospray Ions Using Charge Detection Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 1995, 9, 1528–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keifer DZ; Pierson EE; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry: Weighing Heavier Things, Analyst 2017, 142, 1654–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceres P; Zlotnick A Weak Protein-Protein Interactions are Sufficient to Drive Assembly of Hepatitis B Virus Capsids. Biochem. 2002, 41, 11525–11531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zlotnick A; Johnson JM; Wingfield PW; Stahl SJ; Endres D A Theoretical Model Successfully Identifies Features of Hepatitis B Virus Capsid Assembly. Biochem. 1999, 38, 14644–14652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uetrecht C; Versluis C; Watts NR; Roos WH; Wuite GJL; Wingfield PT; Steven AC; Heck AJR High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry of Viral Assemblies: Molecular Composition and Stability of Dimorphic Hepatitis B Virus Capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2008, 105, 9216–9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uetrecht C; Barbu IM; Shoemaker GK; van Duijn E; Heck AJR Interrogating Viral Capsid Assembly With Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry . Nat. Chem 2011, 3, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes K; Shepherd DA; Ashcroft AE; Whelan M; Rowlands DJ; Stonehouse NJ Assembly Pathway of Hepatitis B Core Virus-like Particles from Genetically Fused Dimers. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 16238–16245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierson EE; Keifer DZ; Selzer L; Lee LS; Contino NC; Wang JCY; Zlotnick A; Jarrold MF Detection of Late Intermediates in Virus Capsid Assembly by Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 3536–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kler S; Asor R; Li C; Ginsburg A; Harries D; Oppenheim A; Zlotnick A; Raviv U RNA Encapsidation by SV40-Derived Nanoparticles Follows a Rapid Two-State Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8823–8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tresset G; Cle Coeur C; Bryche JF; Tatou M; Zeghal M; Charpilienne A; Poncet D; Constantin D; Bressanelli S Norovirus Capsid Proteins Self-Assemble through Biphasic Kinetics via Long-Lived Stave-like Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 15373–15381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tresset G; Decouche V; Bryche JF; Charpilienne A; Le Coeur C; Barbier C; Squires G; Zeghal M; Poncet D; Bressanelli S Unusual Self-Assembly Properties of Norovirus Newbury2 Virus-Like Particles. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2013, 537, 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zlotnick A; Ceres P; Singh S; Johnson JM A Small Molecule Inhibits and Misdirects Assembly of Hepatitis B Virus Capsids. J. Virol 2002, 76, 4848–4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Contino NC; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry for Single Ions With a Limit of Detection of 30 Charges. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2013, 345-347, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Contino NC; Pierson EE; Keifer DZ; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry with Resolved Charge States. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2013, 24, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierson EE; Keifer DZ; Contino NC; Jarrold MF Probing Higher Order Multimers of Pyruvate Kinase With Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2013, 337, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierson EE; Contino NC; Keifer DZ; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry for Single Ions With an Uncertainty in the Charge Measurement of 0.65 e. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 2015, 26, 1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keifer DZ; Shinholt DL; Jarrold MF Charge Detection Mass Spectrometry With Almost Perfect Charge Accuracy, Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 10330–10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutomski CA; Lyktey NA; Zhao Z; Pierson EE; Zlotnick A; Jarrold MF HBV Capsid Assembly Occurs Through Overgrowth and Relaxation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (submitted). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crowther RA; Kiselev NA; Bottcher B; Berriman JA; Borisova GP; Ose V; Pumpens P Three-Dimensional Structure of Hepatitis B Virus Core Particles Determined by Electron Cryomicroscopy. Cell 1994, 77, 943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wingfield PT; Stahl SJ; Williams RW; Steven AC Hepatitis Core Antigen Produced in Escherichia coli: Subunit Composition, Conformational Analysis, and In Vitro Capsid Assembly. Biochem. 1995, 34, 4919–4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selzer L; Katen SP; Zlotnick A The Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein Intradimer Interface Modulates Capsid Assembly and Stability. Biochem. 2014, 53, 5496–5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zlotnick A; Cheng N; Conway JF; Booy FP; Steven AC; Stahl SJ; Wingfield PT Dimorphism of Hepatitis B Virus Capsids Is Strongly Influenced by the C-Terminus of the Capsid Protein. Biochem. 1996, 35, 7412–7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginsburg A; Ben-Nun T; Asor R; Shemesh A; Ringel I; Raviv U Reciprocal Grids: A Hierarchical Algorithm for Computing Solution X-ray Scattering Curves from Supramolecular Complexes at High Resolution. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2016, 56, 1518–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaynes ET Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Phys. Rev 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luque A; Reguera D; Morozov A; Rudnick J; Bruinsma R Physics of Shell Assembly: Line Tension, Hole implosion, and Closure Catastrophe, J. Chem. Phys 2012, 136, 184507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]