Abstract

The photocatalytic conversion of the greenhouse gas CO2 to chemical fuels such as hydrocarbons and alcohols continues to be a promising technology for renewable generation of energy. Major advancements have been made in improving the efficiencies and product selectiveness of currently known CO2 reduction electrocatalysts, nonetheless, materials discovery is needed to enable economically viable, industrial-scale CO2 reduction. We report here the largest CO2 photocathode search to date, starting with 68860 candidate materials, using a rational first-principles computation-based screening strategy to evaluate synthesizability, corrosion resistance, visible-light absorption, and compatibility of the electronic structure with fuel synthesis. The results confirm the observation of the literature that few materials meet the stringent CO2 photocathode requirements, with only 52 materials meeting all requirements. The results are well validated with respect to the literature, with 9 of these materials having been studied for CO2 reduction, and the remaining 43 materials are discoveries from our pipeline that merit further investigation.

While the conversion of greenhouse CO2 to chemical fuels offers a promising renewable energy technology, there is a dire need for new materials. Here, authors report the largest CO2 photocathode search using a first-principles approach to identify both known and unreported candidate photocatalysts.

Introduction

The photocatalytic conversion of CO2 to chemical fuels has attracted considerable interest in recent years as it promises a future path to clean, low-cost renewable energy. Among the unresolved challenges impeding economical, industrial-scale, solar-driven reduction of CO2, the most daunting is the dearth of photocatalysts which simultaneously provide high product selectivity, high efficiencies as well as long term durability in the highly reducing conditions needed for CO2 reduction1. While numerous approaches have been used to improve the performance of known photocatalysts, including the use of co-catalysts, sacrificial agents, morphology optimization, and novel architectures such as composite semiconductors, the attempts for finding new photocathode materials have been few and based largely on trial and error1.

Through this work, we aim to accelerate materials innovation by performing the largest photocatalyst search to date2–4, starting with 68,860 materials, and screening for the electronic state as well as electrochemical stability of the candidate materials, to identify 43 new photocathode materials for CO2 reduction. Recent advances in available computing power have facilitated large-scale and predictive first-principles simulations of materials properties through open-source computational databases5–8. Such databases have already aided in an exploratory search of new materials for a variety of applications, such as metallic glasses9, electrolytes for batteries10, and transparent conductors11. Leveraging the Materials Project (MP) database5,6, we use a rational computational search strategy to identify photocathodes based on the intrinsic properties of materials. This screening strategy allows us to identify semiconductors which not only fulfill metrics for synthesizability, corrosion-resistance—under the highly reducing conditions (< −0.5 V vs RHE) needed for CO2 reduction—but also exhibit bandgaps and band-edge energies suited for efficient solar-energy conversion. This computational strategy minimizes the number of computationally expensive electronic structure simulations through a judicious screening of the information which can be queried from existing information in the MP database.

The photocathode materials identified by the tiered computational screening include 9 materials previously reported as CO2 photocathodes, as well as discovery of a set of 43 new candidate photocathodes comprised of 34 previously synthesized materials, and 8, as yet, hypothetical structures, providing new chemical classes, inspiration and future prospect for materials design by optimizing photocathode performance through strategies such as thickness variation, nanostructuring, alloying, defect engineering, and use of co-catalysts. We also apply the screening strategy to forty-five photocathodes reported in the literature in order to highlight its scope and demonstrate its viability in identifying suitable, durable photocathodes. Based on the validation against previously reported photocathodes, we find that this screening strategy is aptly designed to identify promising photocathodes, however, some promising photocathodes may have been excluded due to factors such as current limitations in computing power, short-comings of certain computational methods for particular classes of materials, or the specific choice of the screening criteria.

Results

Computational strategy for discovery of new photocathodes

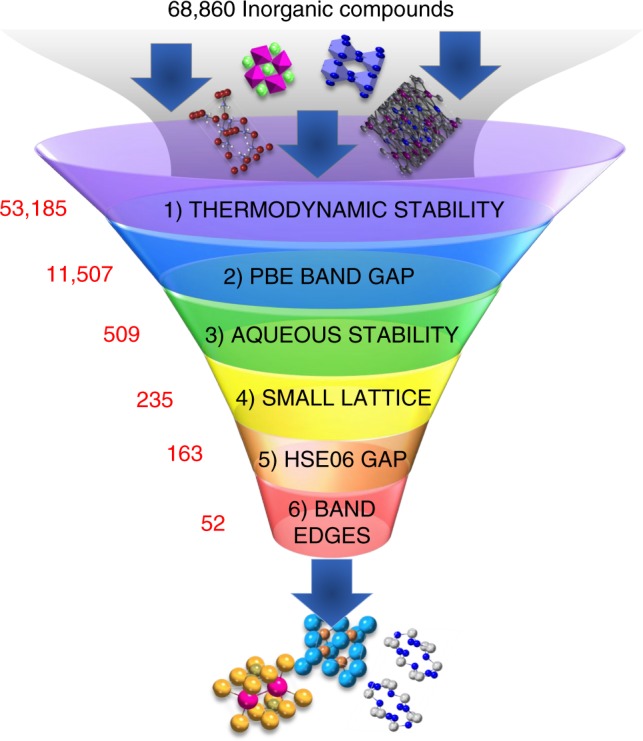

Suitable photocatalyst surfaces supply photo-excited electrons to facilitate the reaction of CO2 with protons in solution. Electrons are excited into the conduction band by the absorption of visible light with a photon energy greater than the bandgap of the photocatalyst material. Electrons of different energies have different thermodynamic propensity for reducing CO2 to different fuels, as shown in Fig. 1. The similarity in the reduction potentials for a broad range of fuels poses a challenge for attaining selective photoreduction of CO2 and an opportunity for computational screening since a moderate range of target conduction band energies can be used to identify photocathodes for practically any fuel. The resulting photocathode screening pipeline, which is specific to CO2 reduction but not to any particular fuel, is shown in Fig. 2 and is composed of six intrinsic property-based screening criteria. The use of progressive tiers, instead of simultaneous evaluation of all target properties, reduces the computational cost associated with the search. The first four tiers are based on computational results already accessible through the MP database, however, the last two tiers are enabled by accurate, more expensive, electronic structure simulations performed specifically for this study. Specifically, the MP database is used to obtain the properties screened in tier 1–4 as well as for accessing the crystal structures which are used for the simulations of tier 5 and 6.

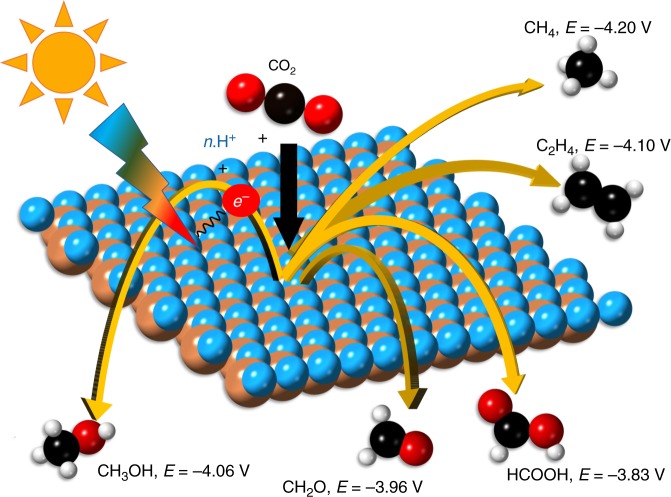

Fig. 1.

A schematic of photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to chemical fuels. Light of sufficient energy can excite electrons across the bandgap of a photocatalyst which can be used to drive the reaction of CO2 with hydrogen ions to several closely competing products. At a neutral pH the potential required for converting to each product is noted. The potential for H+/H2 at this pH is −4.03 eV63 with respect to the vacuum level

Fig. 2.

The selection criteria, as well as the number of materials which satisfy the criterion, are shown for each tier. Note that less than 5% of the semiconductors from tier 2 make it through tier 3, highlighting that very few semiconductors are water-stable at the reducing conditions needed for CO2 reduction

The 68,860 materials available in MP are evaluated using this screening strategy. These materials consist of 34,913 materials reported in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD)12 (the world’s largest database of experimentally synthesized and completely characterized inorganic materials) and 33,947 originating from non-ICSD sources, including hypothetical materials predicted by a variety of procedures such as machine learning models of experimental structures13, ion substitutions in existing structures, and crowd-sourced user submissions using the MP’s crystal toolkit.

The first tier estimates the thermodynamic stability, through a metric based on the computed energy above the convex hull in the composition space, ΔEhull, and provides a proxy for the synthesizability of the candidate materials. ΔEhull is the energy of decomposition of a material into the set of most stable materials at this chemical composition. We select materials which are predicted thermodynamic ground states, ΔEhull = 0 eV.atom−1, as well as materials which are meta-stable up to ΔEhull < 80 meV.atom−114. The cutoff of 80 meV.atom−1 is chosen as approximately 80% of known verified sulfides and oxides are within this limit. Of the original 68,860 materials, 53,185 pass the first tier.

The second tier is designed to select materials which have the potential to utilize the visible-light spectrum (1.7 eV–3.0 eV) which accounts for 44% of the solar radiation. The chosen screening range takes into account that the calculated electronic structure available through the MP database are computed using PBE and PBE + U functionals, which can underestimate bandgaps with respect to experiment by ~40%15,16.

One of the pre-eminent challenges in identifying suitable photocathodes is finding materials which exhibit long-term aqueous stability under reducing conditions. At the reducing potentials necessary for CO2 reduction, which typically fall between 0 and −1.0 V vs RHE1,17,18, most materials reduce to their metallic forms or hydrolyze. Generally, materials with larger cation and anion sizes and/or small size differences remain stable in aqueous media19. Also, multivalent materials tend to have strong lattice energies in comparison to monovalent materials which renders them more likely to be stable in water in comparison to their monovalent counterparts19. However, as lattice and hydration enthalpy, and entropy of dissolution and hydration contribute to the Gibbs free energy of dissolution of compounds, generalizations with respect to the stability of specific materials is non-trivial, motivating our evaluation of the electrochemical stability of each candidate photocathode19.

In tier 3, we use our recently developed formalism20,21 to screen for electrochemically stable materials from the 11,507 materials which pass tier 2. This formalism uses first-principles simulations to generate phase maps in Eh-pH space, or so-called Pourbaix diagrams. Furthermore, it allows us to estimate the electrochemical stability ΔGpbx, defined as the Gibbs free energy of decomposition of a material to Pourbaix-stable phases at a given pH and potential. We have previously shown that ΔGpbx, together with an analysis of the predicted decomposition products, provides a quantitative measure for the propensity of materials to be stable in water, either by inherent stability or through the development of a passivating film. Materials with ΔGpbx = 0 eV.atom−1 are considered to be stable, whereas, for ΔGpbx > 0, the candidate materials decompose to Pourbaix-stable phases in thermodynamic equilibrium. We additionally demonstrated that materials with ΔGpbx up to 0.5 eV.atom−1 can be metastable due to lack of sufficient driving force for decomposition into Pourbaix-stable phases (referred as decomposed species hereon). An inclusive criteria of ΔGpbx < 0.2 eV.atom−1 for aqueous stability in tier 3 is chosen, also accounting for local temperature and ionic concentration fluctuations of ~10−2 M. We screen for materials which decompose to at least one solid phase such that a passivation layer might form on the surface to prevent further corrosion. Only 509 materials, fewer than 5% of those from the previous tier pass the aqueous stability screening. The significant reduction of candidates underscores the importance of determining aqueous stability of potential photocathodes and highlights that electrochemical stability is a much more discriminating requirement than e.g., absorption of visible light.

More generous criteria for aqueous stability for e.g. ΔGpbx < 1.5 eV.atom−1 results in 3054 candidate materials. While this expands the list of candidate materials, the materials with large ΔGpbx exhibit a high probability of either corrosion or formation of passivating surface films. Passivating films may protect the catalyst surface from corrosion and may even aid in charge migration or separation. However, if the passivation layers exhibit unfavorable electronic properties, for instance if they are electronically insulating they can be detrimental to the photocatalytic reaction. While it is difficult to undertake high-accuracy simulations of tier 5 and 6 for such large number of materials, future advancements in computing power may allow us to relax the aqueous stability criteria to study more materials as well as optimize the catalyst-passivation layer interface for high-efficiency CO2 reduction.

We emphasize that the computational screening presented here addresses the challenge of identifying water-stable photocatalysts. In the future, developments in computational methods can facilitate a search for materials which are suited for vapor-phase CO2 reduction or CO2 reduction in non-aqueous solvents, both of which have shown promising improvements in kinetics and corrosion control22,23.

The last two tiers require computationally expensive density-functional theory (DFT) simulations using the HSE06 functional for accurate estimates of the electronic structure, and hence we pre-screen candidates at this stage which are computationally tractable. More specifically, we include materials with 20 or fewer atoms per unit cell, which retains 235 of the 509 materials from tier 3. In tier 5 we filter materials using a hybrid exchange-correlation functional, HSE06, which typically exhibits improved treatment of semiconductor bandgaps, . We retain materials with absorbance in the visible-light range and, allowing for a possible decrease in absorbance due to surface states24, up to 0.5 eV beyond the visible-light energy. In total, 163 materials met the criteria of tier 5.

In order to reduce CO2, the conduction band minimum (CBM) of a candidate photocatalyst surface should exceed the equilibrium CO2 energy, which is approximately −4.2 eV with respect to the vacuum level1,17 for most of the reduced products shown in Fig. 1. The single electron reduction of CO2 to the anion radical exhibits a higher potential of −2.5 eV1. In tier 6, we filter materials surfaces whose CBM are larger than the free energy of reduction or formation of the radical, i.e., −4.3 eV < < −2.4 eV. Explicit effects of adsorbates, surface reconstructions or solvation is beyond the scope of our study, nonetheless, we note that the large 2 eV window for band-edge criteria abates omission of promising materials. The exploration of reaction mechanisms via calculations of reaction energy barriers, adsorption energy calculations and experimental measurements can shine further light on the efficiency of the individual materials’ surfaces and their selectivity towards specific products.

It is noteworthy that the computational screening performed in this work relies on DFT simulations which has well-known limitations in e.g., the accuracy of the reported bandgap. The use of a consistent DFT simulation parameter sets for computations within a tier and also between the computations of different tiers suggests that any errors are likely systematic, and thus qualitative trends between investigated materials are more likely to be preserved. In addition, our final screening tiers use high-accuracy electronic structure simulations which are specifically helpful in overcoming the limitations associated with bandgap predictions.

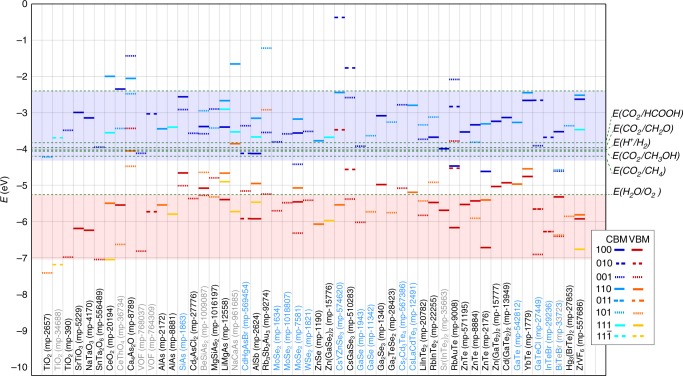

Figure 3 shows the CBM and the valence band maxima (VBM) for the 52 materials, 43 new and 9 previously tested for CO2 reduction, which satisfy the criteria for all tiers. The , , ICSD-id, materials-id, number of sites in the cell, ΔEhull, band-edge alignments and ΔGpbx for the 235 materials which pass tier 4 are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Surfaces of materials with CBM in the blue shaded region are deemed excellent photocathode candidates for CO2 reduction and hydrogen production and those with VBM in the red shaded region may also oxidize water. Before we discuss these newly identified photocathodes and their chemistries, we turn to assess the strengths and short-comings of this screening strategy by applying it to known photocathodes.

Fig. 3.

Band-edge energies of materials which pass tier 6 are shown on the y-axis and the x-axis labels show the corresponding materials formula and the Materials Project material-id in parenthesis. The conduction band minima (CBM) of different planes are marked with lines in shades of blue and the valence band maxima (VBM) in the shades of red as shown in the figure legend. The energy levels E(CO2/HCOOH), E(CO2/HCHO), E(H+/H2), E(CO2/CH3OH), E(CO2/CH4), and E(H2O/O2), in decreasing order of energy, are shown as green dashed lines. Note that all potentials are with respect to the vacuum level that is set to 0 eV. The blues shaded region shows the CBM which satisfy the criteria of tier 6. Materials which are reported in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are labeled in black, layered-materials are labeled in blue, and those which do not have a corresponding ICSD structure are labeled in gray. BiTeBr is labeled in blue and gray since it is a hypothetical layered material. The phonon spectra of the hypothetical materials are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1

Scope of screening: validation against known photocathodes

The following 45 materials have been reported in the literature as experimentally demonstrating some evidence of photocatalytic CO2 reduction:1,25,26

bulk materials—BiVO4, CuInGaSe2, CuInS2, CuInSe2, GaP, InP, and WO3

nanoparticles—BaTiO3, Bi2S3, Bi2WO6, CdS, CeO2, CuFeO2, CuGaO2, CuO, Cu2O, Cu2SnZnS4, In2Ge2O7, InNbO4, InTaO4, KNbO3, K2Ti6O13, LiNbO3, MnS, MgO, MoSe2, NaNbO3, NaTaO3, Si, SiC, SrTiO3, TaNO, Ta2O5, TiO2, W18O49, WSe2, ZnO, ZnS, ZnSe, Zn2SnO4, ZnTe, and ZrO2

mesoporous materials—Ga2O3, Zn(GaO2)2, and Zn2GeO4

We note that the crystal structure is not always reported along with the chemical composition, which necessitates the consideration of several polymorphs per reported material. Only CuInGaSe2 is not represented by a corresponding phase in the MP database and we note that no crystal structure of CuInGaSe2 is reported in the ICSD. The remaining 44 materials comprise a total of 352 phases, whereof 267 phases satisfy the thermodynamic stability criteria of tier 1.

Somewhat surprisingly, tier 2, which removes phases with low probability for visible light absorption, retains 202 phases, corresponding to only 27 materials. Eliminated materials include: CuFeO2, CuGaO2, CuInS2, CuInSe2, CuO, Cu2O, Cu2SnZnS4, InP, MnS, ZnO, Zn2SO4 and W18O49 with < 1 eV, and InNbO4, InTaO4, K2Ti6O13, MgO, and ZrO2 which exhibit large gaps with > 2.5 eV. These results are overall consistent with experimental measurements. For example, CuO is not a visible-gap material (experimentally measured band gap of 1.2 eV27) thus correctly does not pass tier 2. While most materials exhibit PBE bandgaps that are underestimated by ~40% with respect to their experimental gaps, there are pathological exceptions. For example, Cu2O is a known strongly correlated-electron material which exhibits a measured bandgap of 2.2 eV28,29, however this material is eliminated in tier 2 due to the severe underprediction of its PBE gap, beyond even the generous limits imposed here (1.0 eV < < 2.5 eV). The MP database uses the PBE+U method30 to compute the bandgaps of several of the transition metal oxides (see https://materialsproject.org/docs/calculations) to minimize the electron-correlation error from the PBE method. However, such corrections are not employed for the Cu-O chemical family, as a single U value for all Cu oxides has not been found to be universally beneficial31.

The most stringent screening is the aqueous stability tier 3, where only 12 materials corresponding to 30 possible phases, satisfy the criteria. These materials are TiO2, CeO2, Ga2O3, MoSe2, NaTaO3, Si, SrTiO3, Ta2O5, Zn(GaO2)2, ZnTe, ZnSe and WSe2. All the other phases exhibit much larger ΔGpbx, up to 2.6 eV.atom−1, and are expected to completely corrode or—in the best case scenario—passivate. The latter scenario depends critically on the ionic conductivity of the surface film and its ability to protect the underlying material from corrosion. For instance, WO3 is expected to leach oxygen, to form W metal.

In the subsequent tier 4, where the computational cost is considered, 26 of the 30 phases remain for which HSE06 simulations were performed. After applying the remaining two tiers, the previously tested rutile- and anatase-phases of TiO2, cubic-phases of SrTiO3, CeO2, and NaTaO3, the 2H-phase of MoSe2 and WSe2 and the zinc-blende phases of ZnTe and ZnSe are all ascertained as suitable photocathodes. Some new, untested polymorphs of these materials, listed in Supplementary Table 2, were also identified.

It is noteworthy that the aqueous stability screening eliminated the largest proportion of literature-reported photocathodes, demonstrating that our screening procedure is highly selective of materials which are robust under the necessary CO2 electroreduction conditions. All materials which emerge from the screening and have been tested for CO2 reduction show appreciable photocurrent. It can be concluded from this analysis that the materials predicted as photocathodes in our work have the potential to be excellent photocatalysts and remain robust during operation.

The identified photocathodes

Among the 52 photocathodes which emerge from the screening, all but eight materials have a corresponding ICSD-id (as shown in Table 1). Among the 44 ICSD materials, barring wurtzite-AlAs, all the materials have been previously synthesized, see Supplementary Table 3. Furthermore, 15 of the screened materials are layered materials as indicated in Fig. 3, a promising class of photocatalyst materials32. Among the 52 photocathodes predicted in this work, 43—to our knowledge—have not been tested for CO2 reduction as reported in the open literature.

Table 1.

The spacegroup (SG), the lattice constants (a, b, c in Å, α, β, γ in °), bandgaps computed with HSE06 functional ( in eV), the MP material-id (mp-id) and the ICSD-id for all 52 materials which emerge as suitable photocathodes from the screening are listed in the table

| Formula | SG | a | b | c | α | β | γ | mp-id | ICSD-id | Exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | P42/mnm | 2.97 | 4.65 | 4.65 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 3.2 (D) | mp-2657 | 202240 | Y [33] |

| TiO2 | C2/c | 3.82 | 3.82 | 5.43 | 109.7 | 109.7 | 90.1 | 3.5 (I) | mp-34688 | None | N |

| TiO2 | I41/amd | 3.81 | 3.81 | 5.56 | 110.0 | 110.0 | 90.0 | 3.5 (I) | mp-390 | 202242 | Y63 |

| SrTiO3 | Pm3̄m | 3.95 | 3.95 | 3.95 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 3.2 (I) | mp-5229 | 80872 | Y35 |

| NaTaO3 | Pm3̄m | 3.98 | 3.98 | 3.98 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 3.1 (I) | mp-4170 | 88378 | Y64 |

| Ta2SnO6 | Cc | 4.92 | 5.62 | 9.06 | 91.4 | 105.8 | 90.0 | 3.1 (I) | mp-556489 | 54078 | N |

| CeO2 | Fm3̄m | 3.87 | 3.87 | 3.87 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.5 (I) | mp-20194 | 164225 | Y65 |

| CeThO4 | P4/mmm | 3.92 | 7.84 | 6.79 | 30.0 | 54.7 | 60.0 | 3.2 (I) | mp-36734 | None | N |

| Ca4As2O | I4/mmm | 4.57 | 4.57 | 8.39 | 105.8 | 105.8 | 90.0 | 2.0 (I) | mp-8789 | 68203 | N |

| VOF | P21/c | 5.19 | 5.00 | 5.10 | 90.0 | 101.8 | 90.0 | 2.7 (D) | mp-768037 | None | N |

| VOF | Pmmn | 3.87 | 3.17 | 6.28 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 2.7 (I) | mp-764309 | None | N |

| AlAs | F3̄m | 4.05 | 4.05 | 4.05 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.1 (I) | mp-2172 | 606009 | N |

| AlAs | P63mc | 4.05 | 4.05 | 6.65 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 2.4 (I) | mp-8881 | 67771 | N |

| SiAs | C2/m | 3.70 | 9.06 | 10.23 | 111.8 | 90.0 | 101.8 | 2.1 (I) | mp-1863 | 43227 | N |

| Cd2AsCl2 | P21/c | 8.00 | 8.22 | 9.37 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 116.9 | 1.8 (I) | mp-27776 | 26013 | N |

| BeSiAs2 | I4̄2d | 5.38 | 5.38 | 6.57 | 114.2 | 114.2 | 90.0 | 1.7 (D) | mp-1009087 | None | N |

| MgSiAs2 | I4̄2d | 5.95 | 5.95 | 6.88 | 115.6 | 115.6 | 90.0 | 1.9 (D) | mp-1016197 | 182367 | N |

| LiMgAs | F4̄3m | 4.39 | 4.39 | 4.39 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.0 (I) | mp-12558 | 107954 | N |

| NaCaAs | F4̄3m | 4.93 | 4.93 | 4.93 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.2 (I) | mp-961685 | None | N |

| CdHgAsBr | Pmma | 4.80 | 11.06 | 10.21 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 1.8 (I) | mp-569454 | 240354 | N |

| AlSb | F4̄3m | 4.41 | 4.41 | 4.41 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 1.8 (I) | mp-2624 | 609288 | N |

| Rb3Sb2Au3 | R3̄m | 8.29 | 8.29 | 8.29 | 47.4 | 47.4 | 47.4 | 1.7 (D) | mp-9274 | 78978 | N |

| MoSe2 | P63/mmc | 3.33 | 3.33 | 15.45 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 1.9 (D) | mp-1634 | 49800 | Y25 |

| MoSe2 | P63/mmc | 3.33 | 3.33 | 14.27 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 1.9 (I) | mp-1018807 | 644346 | N |

| MoSe2 | R3m | 7.61 | 7.61 | 7.61 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 25.3 | 1.9 (I) | mp-7581 | 16948 | N |

| WSe2 | P63/mmc | 3.33 | 3.33 | 15.07 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 1.9 (I) | mp-1821 | 40752 | Y25 |

| ZnSe | F4̄3m | 4.06 | 4.06 | 4.06 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.3 (D) | mp-1190 | 652224 | Y26 |

| Zn(GaSe2)2 | I4̄ | 5.64 | 5.64 | 6.81 | 114.5 | 114.5 | 90.0 | 2.3 (D) | mp-15776 | 168594 | N |

| CsYZnSe3 | Cmcm | 4.18 | 8.37 | 11.03 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 104.5 | 3.1 (D) | mp-574620 | 280847 | N |

| CsGaSe3 | P21/c | 6.91 | 7.97 | 13.30 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 106.5 | 2.8 (I) | mp-510283 | 98670 | N |

| GaSe | P63/mmc | 3.82 | 3.82 | 17.75 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 2.1 (I) | mp-1943 | 63122 | N |

| GaSe | R3m | 9.13 | 9.13 | 9.13 | 24.1 | 24.1 | 24.1 | 2.1 (I) | mp-11342 | 73388 | N |

| Ga2Se3 | Cc | 6.81 | 6.77 | 6.90 | 81.0 | 60.4 | 71.4 | 1.9 (D) | mp-1340 | 37168 | N |

| Ga2TeSe2 | I41md | 7.44 | 7.44 | 7.61 | 119.3 | 119.3 | 90.0 | 2.5 (D) | mp-28423 | 64617 | N |

| Cs2Cd3Te4 | Ibam | 6.89 | 10.92 | 10.92 | 75.9 | 71.6 | 71.6 | 2.3 (D) | mp-567386 | 90369 | N |

| CsLaCdTe3 | Cmcm | 4.72 | 8.98 | 12.31 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 105.2 | 2.4 (D) | mp-12491 | 173316 | N |

| LiInTe2 | I4̄r2d | 6.54 | 6.54 | 7.88 | 114.5 | 114.5 | 90.0 | 2.1 (D) | mp-20782 | 639906 | N |

| RbInTe2 | I4/mcm | 7.42 | 7.42 | 7.42 | 104.9 | 104.9 | 119.1 | 1.8 (I) | mp-22255 | 75346 | N |

| Sr(InTe2)2 | I4/m | 7.21 | 7.21 | 7.21 | 104.5 | 104.5 | 119.8 | 1.7 (I) | mp-35663 | None | N |

| RbAuTe | Pmma | 5.25 | 6.01 | 7.40 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 1.7 (D) | mp-9008 | 71652 | N |

| ZnTe | P31 | 4.37 | 4.37 | 10.70 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 2.0 (D) | mp-571195 | 80076 | N |

| ZnTe | P63mc | 4.37 | 4.37 | 7.18 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 2.1 (D) | mp-8884 | 67779 | N |

| ZnTe | F4̄3m | 4.37 | 4.37 | 4.37 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.1 (D) | mp-2176 | 41984 | Y41 |

| Zn(GaTe2)2 | I4̄ | 6.07 | 6.07 | 7.39 | 114.3 | 114.3 | 90.0 | 1.8 (I) | mp-15777 | 44888 | N |

| Cd(GaTe2)2 | I4̄ | 6.27 | 6.27 | 7.47 | 114.8 | 114.8 | 90.0 | 1.8 (D) | mp-13949 | 25646 | N |

| GaTe | C2/m | 4.15 | 9.35 | 10.82 | 106.1 | 90.0 | 102.8 | 1.7 (D) | mp-542812 | 153456 | N |

| YbTe | Fm3̄m | 4.50 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 2.1 (I) | mp-1779 | 653185 | N |

| GaTeCl | Pnnm | 4.16 | 5.98 | 15.91 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 3.0 (D) | mp-27449 | 15582 | N |

| InTeBr | P21/c | 7.84 | 7.74 | 8.54 | 90.0 | 117.2 | 90.0 | 2.6 (D) | mp-29236 | 100705 | N |

| BiTeBr | P3m1 | 4.36 | 4.36 | 6.91 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 120.0 | 1.8 (I) | mp-33723 | None | N |

| Hg3(TeBr)2 | I213 | 8.59 | 8.59 | 8.59 | 109.5 | 109.5 | 109.5 | 2.5 (D) | mp-27853 | 27402 | N |

| ZrVF6 | Fm3̄m | 5.87 | 5.87 | 5.87 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 3.3 (I) | mp-557686 | 73354 | N |

Materials with reported activity for CO2 reduction are denoted in the Exp column as Y along with the corresponding reference and N otherwise. Direct and indirect bandgaps are denoted (D) and (I), respectively, in the column

Among the 43 newly identified photocathodes listed in Table 1, 35 have been previously synthesized (see Supplementary Table 3 for the references of synthesis procedures) and 8 are as-yet hypothetical materials. The phonon spectra of the 8 hypothetical materials, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1, show that BeSiAs2, BiTeBr, CeThO4, and NaCaAs are dynamically stable. However, the monoclinic TiO2, SrIn2Te4 and the two phases of VOF are dynamically unstable and are removed from the list of high-ranking candidates. The crystal structure of all the 52 identified photocathodes are shown in Supplementary Figs 3–54.

We also note that most prior experimental data on photocatalytic CO2 reduction focuses on oxides. Our work identifies promising photocathodes from a wider range of chemistries which may have been overlooked, including 11 oxides, 9 arsenides, 2 antimonides, 12 selenides, 17 tellurides, and one transition-metal fluoride. Among the 9 previously known photocathodes, 5 are oxides and 3 are selenides. Only one of the 17 predicted tellurides has been tested, i.e., ZnTe. To the best of our knowledge, none of the arsenide or antimonide photocathodes identified in this work have been tested before.

The rutile- and anatase-phases of TiO2 are undoubtedly the most studied photocathodes thus far33,34. By using different morphologies and various co-catalysts, a range of reduced products including ethane, methanol, formic acid, and CO have been obtained from TiO2 catalysts33,34. Other previously studied oxides include SrTiO3, NaTaO3, and CeO2, each of which can form nanoparticles35 with reported CO2 reduction activity.

Among the oxide photocathodes identified in this work, CeThO4 is an as yet hypothetical structure, whereas SnTa2O6 and Ca4As2O have been synthesized36,37. Heating of KTaO3 and SnCl2 at a high-temperature of 673 K for 24 h produces SnTa2O636 and the reaction of Ca3P2 and Ca3As2 yields Ca4As2O37. SnTa2O6 was recognized as a promising photocathode by another study38 but it is yet to be experimentally tested. Extraordinarily, none of the identified arsenides have been tested for CO2 reduction, even the commercially well-used, high-electron mobility, zinc blende-AlAs. Barring wurtzite-AlAs, BeSiAs2, and NaCaAs, all candidate arsenides have been previously synthesized. Typically, they are produced from prolonged high-temperature reactions of constituent elements or compound-phases mixed in a stoichiometric ratio.

Cationic substitutions in the MgSiAs2 and the LiCaAs phase yields the hypothetical materials BeSiAs2 and NaCaAs, presenting an operative technique to modulate the band-edge energies as shown in Fig. 3. Likewise, the bandgap, band-edge positions and the band-transitions of layered materials, such as the SiAs and CdHgAsBr, can be altered by varying the number of layers, intercalation or application of strain, thus, providing added avenues to tune product selectivity32.

Two antimonides are identified as promising photocathodes, the high-temperature cubic-phase of AlSb and the trigonal Rb3Sb2Au3. Both the materials have been synthesized before but neither has been tested for CO2 reduction.

Compared to oxides, selenides have lower bandgaps in the visible-region and can utilize a large fraction of the solar spectrum. Among the twelve identified selenide photocathodes only three have been tested before, the transition-metal dichalcogenides, 2H-MoSe2 (mp-1634) and 2H-WSe2 (mp-1821)25 and the cubic-ZnSe (mp-1190) nanosheets with a Ni co-catalyst26. All three reduce CO2 to CO.

All other identified selenide photocathodes, a 2-layered MoSe2 polymorph, a 4-layered MoSe2 polymorph, Zn(GaSe2)2, CsYZnSe3, CsGaSe3, hexagonal-GaSe, trigonal-GaSe, Ga2Se3, and Ga2TeSe3 have been experimentally synthesized but are yet to be tested for CO2 reduction. High-quality crystals of these materials can be grown via high-temperature synthesis methods such as the Bridgman technique and chemical vapor transport (CVT).

The hexagonal-GaSe (mp-1943) is particularly promising since both n- and p-type crystals can be synthesized for this phase39. The defected zinc-blende structures of Ga2TeSe2 and Ga2Se3 also promise defect-mediated faster mobility of photogenerated electrons and holes. Furthermore, these two materials have direct gaps which can allow direct photon-induced electron transfer without phonon-assistance. In total, half of the predicted twelve selenides are layered materials.

A large number of telluride photocathodes have been identified through this work, largely because these materials exhibit excellent aqueous stability under reducing conditions, which is intuitive given the significantly larger aqueous stability region of elemental Te, as compared to Se and S40. Among the 17 telluride photocathodes only the zinc-blende phase of ZnTe (mp-2176), grown on Zn/ZnO nanowires, has been tested before and reduces CO2 to CO41.

Two new phases of ZnTe, a trigonal-42, and a hexagonal43-phase have been identified as photocathodes. As a high-pressure phase, the trigonal structure is not as suitable as the hexagonal phase for CO2 reduction. In addition to the ZnTe phases, two other binary telluride photocathodes are identified through this work, YbTe and the layered GaTe.

All candidate tellurides except BiTeBr have been synthesized before. Akin to the selenides, the tellurides have been synthesized using the Bridgman technique, CVT and also the reactive halide synthesis method. Most of the ternary tellurides have reported facile synthesis procedures and are stable in air. However, previous work shows that obtaining phase pure Zn(GaTe2)244, is challenging, LiInTe2 oxidizes in air45, and GaTeCl and InTeBr are hygroscopic46. Notably, the layered ternary Cs2Cd3Te447 and CsLaCdTe348 exhibit bandgaps 2.3 eV and 2.4 eV, which are much larger than that of the 1.5 V of the well-known CdTe49.

The compounds that have been successfully synthesized with p-type conductivity are perhaps the most amenable to experimental investigation as CO2 photocathodes, and those with no reported conductivity or doping studies may require development of doping strategies before photoelectrochemical performance can be assessed. The presence of steps, edges, defects, grain-boundaries, and surface adsorbates have been known to have significant effects on catalyst rates and selectivities for CO2 reduction specifically50, which is not addressed in this study but is likely to further differentiate the screened materials. While the experimental path connecting this computational screening to an operational device may be quite tortuous, our screening pipeline is designed to identify the materials and chemistry classes that, upon successful traversal of that path, have the requisite operational stability to create a deployable technology.

Discussion

To summarize, we have performed the largest exploratory search, covering 68,860 materials, for CO2 reduction photocathodes with targeted intrinsic properties, including corrosion resistance, and identified 39 new materials which have never been reported for this functionality before. We design and employ a computational screening strategy which makes the monolithic task of computing accurate electronic structure properties manageable by pre-screening materials based on computed properties available through first-principles simulations-based databases. After applying the screening strategy to photocathodes reported in the literature, we find that the strategy is highly selective of materials which are extremely robust in the reducing conditions needed for CO2 reduction. The predicted materials include diverse chemistries, such as arsenides, tellurides, selenides, and oxides and include several layered materials. This diversity presents ample opportunity for further materials design via alloying, application of strain, use of co-catalyst or use of tandem designs. Even though special emphasis is placed on materials with surfaces which can reduce CO2, several materials obtained from the screening strategy are also suitable for solar-driven water oxidation and hydrogen production or as solar energy absorbers. We hope that this work will open up new avenues and inspiration for materials optimization towards viable solar fuel production.

Methods

All the simulations are based on density functional theory using the projector-augmented wave method as implemented in the plane-wave code VASP51–54. The ground state structures, energies as well as the bandgap computation, in tier 1 and 2, use the PAW method for modeling core electrons and the Generalized Gradient Approximation with the PBE parameterization is used for the exchange and correlation55–58. An energy cutoff of 520 eV and a k-point mesh of 1000/number of atoms in the cell is used for all simulations. The energy difference for ionic convergence is set to 0.0005 eV × number of atoms in the cell. These parameters yield well-converged structures in most instances59. Some elements have been modeled using PBE+U and an energy correction is used to make them comparable with the PBE calculations60. Oxides containing Co, Cr, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, V, or W are modeled using PBE+U with U values of 3.32 eV, 3.7 eV, 5.3 eV, 3.9 eV, 4.38 eV, 6.2 eV, 3.25 eV, and 6.2 eV, respectively.

An ionic concentration of 10−5 M, activity of solids as 1, temperature of 298 K, and a pressure of 1 atm is assumed for the ΔGpbx computations of tier 3.

To account for the well-known bandgap underestimation problem in PBE and PBE+U methods we adopt the HSE06 functional for tier 5 and 6. HSE06 is a hybrid functional featuring local fractional exact exchange, 25 % for this work, which is predictive for bandgaps for a range of materials61. HSE06 simulations were performed with starting structures as the MP optimized bulk structures, and systems failing to converge are discussed in the Supplementary Note 2. The relation between the and gaps of the materials with pass tier 4 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and discussed in Supplementary Note 2.

Band-edge simulations for tier six were performed in the slab geometry with minimum slab-thickness of 15 Å and a minimum vacuum spacing of 12 Å. Three slabs, the ones with lowest number of atoms for (hkl) where h, k, l = 0, 1, −1, were considered for each of the 163 materials which emerge from tier 5 resulting in a total of 489 surfaces. Slabs were generated by the pymatgen package62. A dipole correction as implemented in VASP was added in the direction perpendicular to the vacuum spacing of the slabs. The slab geometry for surfaces of materials which pass tier 5 consisted of 6–160 atoms for the various surfaces. Due to the large number of atoms as well as the polarity of certain surface terminations, the HSE06 band-edge simulations were converged for 126 surfaces corresponding to 76 materials. Surfaces with more than 72 atoms did not converge in the 96 hrs run time limit. See supplementary methods for the simulation method and parameters used to compute the phonon dispersion of the eight hypothetical materials.

An energy cutoff of 520 eV is employed for all calculations except the more expensive band-edge slab-simulations where the energy cutoff was reduced to 400 eV. A k-point mesh of 1000/(number of atoms in the cell) was used for all but slab calculations where a k-point mesh of 30/a × 30/b × 1 is used (a and b are the cell dimensions in direction perpendicular to the vacuum spacing). All computations are performed with spin polarization and with magnetic ions in a high-spin ferromagnetic initialization.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily funded by the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Energy Innovation Hub, supported through the Office of Science of the DOE under Award Number DE-SC0004993. Computational work was additionally supported by the Materials Project Program (Grant No. KC23MP) through the DOE Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences, and Engineering Division, under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. Computational resources were provided by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562. This work used XSEDE’s Stampede2 at the Texas Advanced Computing Center through allocation #TG-DMR150006.

Author contributions

A.K.S. and K.A.P. conceptualized the project. A.K.S. developed the methodology, performed the simulations, conducted the data analysis reported in this paper and wrote the original draft. J.H.M. helped automate electronic structure simulations. All authors participated in design of the tiered screening pipeline and manuscript editing. K.A.P. and J.M.G. acquired funding for the work and supervised the research reported in the paper.

Data availability

The data that support the results within this paper and other findings of this study are available at https://materialsproject.org/#search/materials, the supplementary information and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information:Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08356-1.

References

- 1.Habisreutinger SN, Schmidt-Mende L, Stolarczyk JK. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and other semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:7372–7408. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Z, Zhou J, Zhu L, Sun Z. MXene: a promising photocatalyst for water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:11446–11452. doi: 10.1039/C6TA04414J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinde A, et al. Discovery of manganese-based solar fuel photoanodes via integration of electronic structure calculations, pourbaix stability modeling, and high-throughput experiments. ACS Energ. Lett. 2017;2:2307–2312. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan Q, et al. Solar fuels photoanode materials discovery by integrating high-throughput theory and experiment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:3040–3043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619940114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong SP, et al. The materials application programming interface (API): a simple, flexible and efficient API for materials data based on REpresentational state transfer (REST) principles. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2015;97:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.10.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain A, et al. The Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013;1:011002. doi: 10.1063/1.4812323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtarolo S, et al. AFLOWLIB.ORG: a distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2012;58:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The NoMaD (Novel Materials Discovery) repository contains full input and output files of calculations in materials science. http://nomad repository.eu (Accessed 13 December 2018).

- 9.Perim E, et al. Spectral descriptors for bulk metallic glasses based on the thermodynamics of competing crystalline phases. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12315. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qu X, et al. The electrolyte genome project: a big data approach in battery materials discovery. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2015;103:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2015.02.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautier R, et al. Prediction and accelerated laboratory discovery of previously unknown 18-electron ABX compounds. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:308. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belsky A, Hellenbrandt M, Karen VL, Luksch P. New developments in the inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design. Acta Crystallogr. B. 2002;58:364–369. doi: 10.1107/S0108768102006948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hautier G, Fischer C, Ehrlacher V, Jain A, Ceder G. Data mined ionic substitutions for the discovery of new compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2010;50:656–663. doi: 10.1021/ic102031h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aykol M, Dwaraknath SS, Sun W, Persson KA. Thermodynamic limit for synthesis of metastable inorganic materials. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaaq0148. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaq0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran F, Blaha P. Accurate band gaps of semiconductors and insulators with a semilocal exchange-correlation potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:226401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.226401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales-García Aacute, Valero R, Illas F. An empirical, yet practical way to predict the band gap in solids by using density functional band structure calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;12:18862–18866. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b07421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott, K., Shukla, A., White, R., Vayenas, C. & Gamboa-Aldeco, M. Mod. Aspect. Electroc. (Springer, 2007).

- 18.Hori, Y. I. Electrochemical CO2 reduction on metal electrodes. In Mod. Aspect. Electroc., 89–189 (Springer 2008).

- 19.Barrett, J. Inorganic Chemistry in Aqueous Solution, vol. 21 (Royal Society of Chemistry 2003).

- 20.Singh AK, et al. Electrochemical stability of metastable materials. Chem. Mater. 2017;29:10159–10167. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b03980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson KA, Waldwick B, Lazic P, Ceder G. Prediction of solid-aqueous equilibria: scheme to combine first-principles calculations of solids with experimental aqueous states. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:235438. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.235438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou, M. et al. Amino-assisted anchoring of CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots on porous g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.130, 13758–13762 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Xu, Y.-F. et al. Enhanced solar-driven gaseous CO2 conversion by CsPbBr3 nanocrystal/pd nanosheet schottky-junction photocatalyst. ACS App. Energy Mater. 1, 5083–5089 (2018).

- 24.Ping Y, Galli G. Optimizing the band edges of tungsten trioxide for water oxidation: a first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:6019–6028. doi: 10.1021/jp410497f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asadi M, et al. Nanostructured transition metal dichalcogenide electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction in ionic liquid. Science. 2016;353:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuehnel MF, et al. ZnSe quantum dots modified with a Ni (cyclam) catalyst for efficient visible-light driven CO2 reduction in water. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:2501–2509. doi: 10.1039/C7SC04429A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musa A, Akomolafe T, Carter M. Production of cuprous oxide, a solar cell material, by thermal oxidation and a study of its physical and electrical properties. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C. 1998;51:305–316. doi: 10.1016/S0927-0248(97)00233-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, et al. Electronic structures of Cu2O, Cu4O3, and CuO: a joint experimental and theoretical study. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;94:245418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.245418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin M, et al. Copper oxide nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9506–9511. doi: 10.1021/ja050006u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anisimov VI, Zaanen J, Andersen OK. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B. 1991;44:943. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.44.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Maxisch T, Ceder G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA + U framework. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:195107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.195107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh AK, Mathew K, Zhuang HL, Hennig RG. Computational screening of 2d materials for photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:1087–1098. doi: 10.1021/jz502646d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Zhao H, Andino JM, Li Y. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction with H2O on TiO2 nanocrystals: Comparison of anatase, rutile, and brookite polymorphs and exploration of surface chemistry. ACS Catal. 2012;2:1817–1828. doi: 10.1021/cs300273q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Low J, Xiao W, Zhou P, Jaroniec M. Enhanced photocatalytic CO2-reduction activity of anatase TiO2 by coexposed {001} and {101} facets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8839–8842. doi: 10.1021/ja5044787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng S, Kar P, Thakur UK, Shankar K. A review on photocatalytic CO2 reduction using perovskite oxide nanomaterials. Nanotechnology. 2018;29:052001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aa9fb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizoguchi H, Sleight AW, Subramanian MA. Low temperature synthesis and characterization of SnTa2O6. Mater. Res. Bull. 2009;44:1022–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2008.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadenfeldt C, Vollert H. Darstellung und kristallstruktur der calciumpnictidoxide Ca4P2O und Ca4As2O. J. Less-Common Met. 1988;144:143–151. doi: 10.1016/0022-5088(88)90126-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velikokhatnyi OI, Kumta PN. Exploring tin tantalates and niobates as prospective catalyst supports for water electrolysis. Phys. B. 2009;404:1737–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2009.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arancia G, Grandolfo M, Manfredotti C, Rizzo A. Electron diffraction study of melt-and vapour-grown GaSe1−xSx single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi A. 1976;33:563–571. doi: 10.1002/pssa.2210330215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brookins, D. G. Eh-pH diagrams for geochemistry (Springer Science & Business Media 2012).

- 41.Jang JW, et al. Aqueous-solution route to zinc telluride films for application to CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. 2014;53:5852–5857. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kusaba K, Weidner DJ. Structure of high pressure phase I in ZnTe. AIP Conf. Proc. 1994;309:553–556. doi: 10.1063/1.46096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar V, Kumar V, Dwivedi D. Growth and characterization of zinc telluride thin films for photovoltaic applications. Phys. Scr. 2012;86:015604. doi: 10.1088/0031-8949/86/01/015604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woolley J, Ray B. Effects of solid solution of Ga2Te3 with AIIBVI tellurides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 1960;16:102–106. doi: 10.1016/0022-3697(60)90079-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kühn G, Schumann B, Oppermann D, Neumann H, Sobotta H. Preparation, structure, and infrared lattice vibrations of LiInTe2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1985;531:61–66. doi: 10.1002/zaac.19855311209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kniep R, Wilms A, Beister HJ. Phase relations in Ga2X3-GaY3 systems (X = Se, Te; Y = Cl, Br, I)—Crystal growth, structural relations and optical absorption of intermediate compounds GaXY. Mater. Res. Bull. 1983;18:615–620. doi: 10.1016/0025-5408(83)90220-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Narducci AA, Ibers JA. Syntheses, crystal structures, and band gaps of Cs2Cd3Te4 and Rb2Cd3Te4. J. Alloy. Compd. 2000;306:170–174. doi: 10.1016/S0925-8388(00)00795-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Chen L, Wu LM, Chan GH, Van Duyne RP. Syntheses, crystal and band structures, and magnetic and optical properties of new CsLnCdTe3 (Ln = La, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd- Tm, and Lu) Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:855–862. doi: 10.1021/ic7016402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gutowski, J. Cdte: band gap. In New data and updates for IV-IV, III-V, II-VI and I-VII compounds, their mixed crystals and diluted magnetic semiconductors, 329 (Springer 2011).

- 50.Mariano RG, McKelvey K, White HS, Kanan MW. Selective increase in CO2 electroreduction activity at grain-boundary surface terminations. Science. 2017;358:1187–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kresse G, Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kresse G, Hafner J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;49:14251. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 1996;6:15–50. doi: 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kresse G, Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple [phys. rev. lett. 77, 3865 (1996)] Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:1396–1396. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jain A, et al. A high-throughput infrastructure for density functional theory calculations. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2011;50:2295–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2011.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jain A, et al. Formation enthalpies by mixing GGA and GGA + U calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:045115. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.045115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krukau AV, Vydrov OA, Izmaylov AF, Scuseria GE. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:224106. doi: 10.1063/1.2404663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ong SP, et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comp. Mater. Sci. 2013;68:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ni M, Leung MK, Leung DY, Sumathy K. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2007;11:401–425. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2005.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li M, et al. Highly efficient and stable photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CH4 over Ru loaded NaTaO3. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:7645–7648. doi: 10.1039/C5CC01124H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh P, Hegde MS. Ce1−xRuxO2−δ (x = 0.05, 0.10): a new high oxygen storage material and pt, pd-free three-way catalyst. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:3337–3345. doi: 10.1021/cm900875s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the results within this paper and other findings of this study are available at https://materialsproject.org/#search/materials, the supplementary information and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.