Abstract

BACKGROUND

A variety of immune-modulating drugs are becoming increasingly used for various cancers. Despite increasing indications and improved efficacy, they are often associated with a wide variety of immune mediated adverse events including colitis that may be refractory to conventional therapy. Although these drugs are being more commonly used by Hematologists and Oncologists, there are still many gastroenterologists who are not familiar with the incidence and natural history of gastrointestinal immune-mediated side effects, as well as the role of infliximab in the management of this condition.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a case of a 63-year-old male with a history of metastatic renal cell carcinoma who presented to our hospital with severe diarrhea. The patient had received his third combination infusion of the anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody Ipilimumab and the immune checkpoint inhibitor Nivolumab and developed severe watery non-bloody diarrhea the same day. He presented to the hospital where he was found to be severely dehydrated and in acute renal failure. An extensive workup was negative for infectious etiologies and he was initiated on high dose intravenous steroids. However, he continued to worsen. A colonoscopy was performed and revealed no endoscopic evidence of inflammation. Random biopsies for histology were obtained which showed mild colitis, and were negative for Cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus. He was diagnosed with severe steroid-refractory colitis induced by Ipilimumab and Nivolumab and was initiated on Infliximab. He responded promptly to it and his diarrhea resolved the next day with progressive resolution of his renal impairment. On follow up his gastrointestinal side symptoms did not recur.

CONCLUSION

Given the increasing use of immune therapy in a variety of cancers, it is important for gastroenterologists to be familiar with their gastrointestinal side effects and comfortable with their management, including prescribing infliximab.

Keywords: Colitis, Infliximab, Biologics, Immune mediated adverse events, Ipilimumab, Nivolumab, Case report

Core tip: A variety of immune-modulating drugs are becoming increasingly used for various cancers. Despite increasing indications and improved efficacy, they are often associated with a wide variety of immune mediated adverse events. We report the first case of metastatic renal cell cancer treated with the anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody Ipilimumab and the immune checkpoint inhibitor Nivolumab to develop severe steroid-refractory colitis, and describe its resolution after treatment with Infliximab.

INTRODUCTION

A variety of immune-modulating drugs are becoming increasingly used for various cancers. Despite increasing indications and improved efficacy, they are often associated with a wide variety of immune mediated adverse events (IMAE), including gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. We report a case of severe steroid-refractory colitis induced by the anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody Ipilimumab and the immune checkpoint inhibitor Nivolumab in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and its resolution after treatment with Infliximab.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63 year male diagnosed with metastatic renal cell carcinoma presents to the hospital with a several day history of diarrhea and fatigue.

History of present illness

The patient had received his third combination infusion of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab and developed severe watery non-bloody diarrhea the same day. He continued to have upwards of 10 watery bowel movements over the next week and ultimately presented to the hospital.

History of past illness

Past medical history included metastatic renal cell carcinoma, deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity and hypertension.

Personal and family history

He had no significant family history of cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and did not have a personal history of alcohol, tobacco, drug use or foreign travel.

Examinations

Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing man, with mild generalized abdominal tenderness and tachycardia. He was found to be severely dehydrated, in acute renal failure (Creatinine 5.5 mg/dL) with a significant leukocytosis (WBC 20.4 103/μL) (Table 1). An extensive infectious workup for diarrhea was performed which was ultimately negative (Table 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen/pelvis was performed which revealed a moderate amount of liquid stool throughout the colon, greatest within the rectosigmoid colon.

Table 1.

Labs at admission

| Items | Data |

| WBC | 20.39 × 109/L |

| Neutrophil | 61% |

| Lymphocytes | 6% |

| Monocytes | 6% |

| Eosinophil | 0% |

| Hemoglobin | 9.9 mmol/L |

| Platelets | 335 × 109/L |

| RDW | 20% |

| Sodium | 132 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 2.8 mmol/L |

| Chloride | 92 mmol/L |

| CO2 | 7 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 486.2 µmol/L |

| Calcium | 2.3 mmol/L |

| Anion gap | 33 mmol/L |

| Albumin | 0.57 mmol/L |

| Phosphorous | 3 mmol/L |

| AST | 15 IU/L |

| ALT | 26 IU/L |

| Total bilirubin | 6.8 µmol/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 110 IU/L |

| Magnesium | 1.1 mmol/L |

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; CO2: Serum carbon dioxide; RDW: Red blood cell distribution width; WBC: White blood cell count.

Table 2.

Infectious workup

| Infectious workup |

| Clostridium difficile toxin B gene DNA PCR |

| Salmonella, shigella/enteroinvasive E coli, campylobacter, shiga toxin 1/2 NAAT |

| Cryptosporidium stool antigen, giardia stool antigen |

| Ova and parasite |

| Yersinia enterocolitica culture |

| Vibrio stool culture |

| Stool cultures |

| Influenza/respiratory synctial virus /rhinovirus/adenovirus/metapneumovirus |

| Blood and urine cultures |

| Cytomegalovirus colon biopsy DNA PCR |

| Herpes simplex virus 1/2 colon biopsy DNA PCR |

NAAT: Nucleic acid amplification test; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

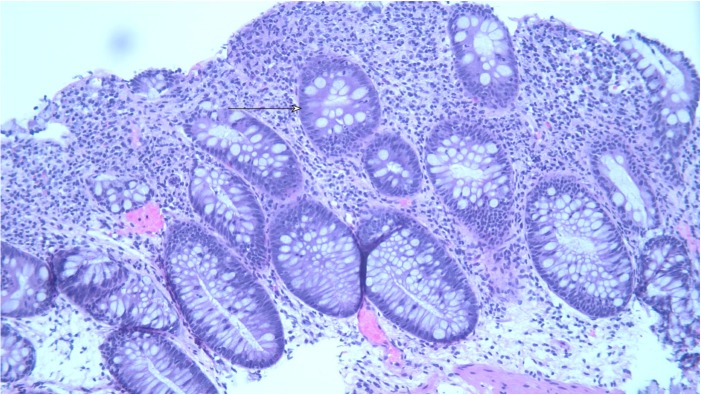

A colonoscopy was obtained and revealed copious amounts of fluid and liquid stool, with over 2 liters of fluid suctioned out, but no endoscopic evidence of inflammation (Figure 1). Random biopsies for histology were obtained, as well as biopsies for cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. His biopsies came back for mild colitis (Figure 2). His cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus PCR were also negative, as was testing for C. difficile, tuberculosis and hepatitis B.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopy revealing copious amounts of fluids and liquid stools in colon without endoscopic evidence of disease after removal.

Figure 2.

Mild active colitis with increased apoptotic bodies in crypts (arrowhead) and increased plasma cells in lamina propria (HE stain, × 100).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was diagnosed with immune-mediated colitis secondary to Ipilimumab and Nivolumab.

TREATMENT

On admission, the patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics, intravenous (IV) fluids and electrolyte replenishment for his metabolic derangements. However given the temporal relationship between the onset of his symptoms and his immune treatment and the negative infectious workup, an immune-mediated colitis was suspected. His antibiotics were discontinued and the patient was started on high dose IV steroids. His renal function and leukocytosis improved but the diarrhea persisted. Ten days after receiving his treatment the gastroenterology service was consulted.

The patient had already been on high-dose steroids, diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil®), and loperamide without relief or resolution. He continued to have 5-10 large volume watery bowel movements a day, and was on continuous IV fluids, a bicarbonate drip as well as aggressive electrolyte replenishment. The patient was also initiated on a trial of mesalamine and subcutaneous octreotide injections with no improvement. After the colonoscopy was performed the patient was initiated on Infliximab 5 mg/kg.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After initiation of Infliximab, the patient noted improvement later the same day. The following day the patient had complete resolution of his diarrhea without any bowel movements. Over the next few days his renal function normalized and all medications were gradually discontinued. He was discharged with a steroid taper and instructed to follow up as an outpatient. On follow up in clinic his colitis had resolved, and he remained symptom free at 3 mo follow up.

DISCUSSION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as Ipilimumab, the CTLA-4 antibody, and Nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 antibody, have been increasingly used in cancers such as metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma but have been associated with several IMAE, including a high incidence of diarrhea and colitis[1]. Although more common in Ipilimumab than Nivolumab, the incidence of colitis is highest when these two drugs are used in combination[2] . These side effects can be severe, and some patients may require the initiation of high dose intravenous steroids such as Methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg per day[3]. However, up to 40% may not respond[4], and many have used Infliximab for treatment of immune-mediated colitis in patients unresponsive to steroid therapy[1-3,5-7]. Infliximab is thought to work in these cases by several mechanisms including opposing the activation of T cells by CTLA-4 antibodies by suppressing the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1 and IL-6[8] , enhancing FOXp3+ regulatory T cells[9], as well as preventing tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha from binding to its receptor, thereby preventing it from recruiting neutrophils to the site of inflammation in the colon[10]. Abdominal CT imaging usually shows mesenteric vessel engorgement, bowel wall thickening, and fluid-filled colonic distention[11]. In one study, endoscopy of patients who ultimately required Infliximab revealed ulceration in 59%, inflammation in 36% and no endoscopic evidence in 5%. Histological findings included chronic inflammation in 68% and acute inflammation in 27%[4]. The grade of diarrhea has not been found to be associated with endoscopic or histologic findings[4,6], and on follow up over a third of patients develop recurrent diarrhea[4]. The median time of response to Infliximab is 2 d, and some patients may need more than one treatment[6]. Caucasians and patients with melanoma seem to have a higher incidence of diarrhea and colitis[5] . Studies have suggested better overall outcomes and survival in patients who develop IMAE[5,12], and in the case of colitis this is thought to be in part secondary to distinct baseline gut microbiota[13]. Although the use of Infliximab has become part of the treatment algorithm for immune-mediated colitis, the influence of a TNF-alpha on the progression of metastatic cancer is unclear, and further studies evaluating long-term effects are needed. To our knowledge this is the first case of renal cell carcinoma treated with both Ipilimumab and Nivolumab with resultant steroid refractory colitis that resolved with Infliximab. Given the increasing use of immune therapy in a variety of cancers, it is important for gastroenterologists to be familiar with their gastrointestinal side effects and management.

CONCLUSION

The incidence of immune-mediated colitis is higher when Nivolumab is used with Ipilimumab, and many patients may require high dose intravenous steroids for therapy. However, up to 40% of patients will not respond and will need to be initiated on infliximab. Gastroenterologists should be able to recognize adverse events related to novel immune therapy agents and be comfortable managing them, including prescribing anti-TNF-alpha inhibitors for immune-mediated colitis. Future studies are needed to evaluate the response to alternate biological agents, long term management of recurrent immune mediated colitis, and the role of TNF-alpha administration on the progression of metastatic cancer.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): D

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed consent statement: Written consent from the patient was obtained.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors disclose no relevant financial conflicts of interest. This paper did not receive any funding. A version of this was submitted to the ACG Scientific Conference 2018.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Peer-review started: October 19, 2018

First decision: November 15, 2018

Article in press: January 9, 2019

P- Reviewer: Osawa S, Poullis A S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Bian YN

Contributor Information

Ammar B Nassri, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32207, United States. anassri@gmail.com.

Valery Muenyi, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32207, United States.

Ahmad AlKhasawneh, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32209, United States.

Bruno De Souza Ribeiro, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32207, United States.

James S Scolapio, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32207, United States.

Miguel Malespin, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Florida at Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL 32207, United States.

Silvio W de Melo Jr, Division of Gastroenterology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR 97239, United States.

References

- 1.Klair JS, Girotra M, Hutchins LF, Caradine KD, Aduli F, Garcia-Saenz-de-Sicilia M. Ipilimumab-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicities: A Management Algorithm. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2132–2139. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spain L, Diem S, Larkin J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng R, Cooper A, Kench J, Watson G, Bye W, McNeil C, Shackel N. Ipilimumab-induced toxicities and the gastroenterologist. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:657–666. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Mao E, Ali N, Qiao W, Trinh VA, Zobniw C, Johnson DH, Samdani R, Lum P, Shuttlesworth G, Blechacz B, Bresalier R, Miller E, Thirumurthi S, Richards D, Raju G, Stroehlein J, Diab A. Endoscopic and Histologic Features of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Mao E, Ali N, Ali FS, Qiao W, Lum P, Raju G, Shuttlesworth G, Stroehlein J, Diab A. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea and colitis in patients with advanced malignancies: retrospective review at MD Anderson. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:37. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geukes Foppen MH, Rozeman EA, van Wilpe S, Postma C, Snaebjornsson P, van Thienen JV, van Leerdam ME, van den Heuvel M, Blank CU, van Dieren J, Haanen JBAG. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open. 2018;3:e000278. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verschuren EC, van den Eertwegh AJ, Wonders J, Slangen RM, van Delft F, van Bodegraven A, Neefjes-Borst A, de Boer NK. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Characteristics of Ipilimumab-Associated Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston RL, Lutzky J, Chodhry A, Barkin JS. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody-induced colitis and its management with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2538–2540. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0641-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quirk SK, Shure AK, Agrawal DK. Immune-mediated adverse events of anticytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma. Transl Res. 2015;166:412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minor DR, Chin K, Kashani-Sabet M. Infliximab in the treatment of anti-CTLA4 antibody (ipilimumab) induced immune-related colitis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:321–325. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim KW, Ramaiya NH, Krajewski KM, Shinagare AB, Howard SA, Jagannathan JP, Ibrahim N. Ipilimumab-associated colitis: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W468–W474. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downey SG, Klapper JA, Smith FO, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Allen TE, Levy CL, Yellin M, Nichol G, White DE, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg SA. Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6681–6688. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaput N, Lepage P, Coutzac C, Soularue E, Le Roux K, Monot C, Boselli L, Routier E, Cassard L, Collins M, Vaysse T, Marthey L, Eggermont A, Asvatourian V, Lanoy E, Mateus C, Robert C, Carbonnel F. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]