Significance

Ratings of the meaningfulness of life have been adopted in UK national surveys and are advocated internationally. This study demonstrates the value of a simple rating of the extent to which people feel that the things they do in life are worthwhile, by documenting positive associations with social relationships and broader social engagement, economic prosperity, mental and physical health, biomarkers, health-related behaviors, and time use. These associations were observed both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, suggesting that feeling life is worthwhile contributes to subsequent well-being and human flourishing at older ages. Given the widely recognized policy importance of promoting subjective well-being at older ages, a wider adoption of worthwhile ratings in large-scale surveys would provide valuable policy-relevant evidence internationally.

Keywords: flourishing, subjective well-being, social relationships, chronic disease, lifestyle

Abstract

The sense that one is living a worthwhile and meaningful life is fundamental to human flourishing and subjective well-being. Here, we investigate the wider implications of feeling that the things one does in life are worthwhile with a sample of 7,304 men and women aged 50 and older (mean 67.2 y). We show that independently of age, sex, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status, higher worthwhile ratings are associated with stronger personal relationships (marriage/partnership, contact with friends), broader social engagement (involvement in civic society, cultural activity, volunteering), less loneliness, greater prosperity (wealth, income), better mental and physical health (self-rated health, depressive symptoms, chronic disease), less chronic pain, less disability, greater upper body strength, faster walking, less obesity and central adiposity, more favorable biomarker profiles (C-reactive protein, plasma fibrinogen, white blood cell count, vitamin D, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol), healthier lifestyles (physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, not smoking), more time spent in social activities and exercising, and less time spent alone or watching television. Longitudinally over a 4-y period, worthwhile ratings predict positive changes in social, economic, health, and behavioral outcomes independently of baseline levels. Sensitivity analyses indicate that these associations are not driven by factors such as prosperity or depressive symptoms, or by outcome levels before the measurement of worthwhile ratings. The feeling that life is filled with worthwhile activities may promote healthy aging and help sustain meaningful social relationships and optimal use of time at older ages.

The sense that one is living a meaningful and worthwhile life is a key component of subjective well-being and human flourishing (1) and is related to a range of social, economic, and health factors (2). The importance of the concept to public policy has been endorsed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the United Kingdom, which has included ratings of how worthwhile people think the things they do in their lives are within the national program of personal well-being since 2011 (3).

Having a strong sense of purpose and meaning in life may be a protective factor in relation to health, with longitudinal studies documenting associations with reduced premature mortality, slower development of age-related disability, reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease, healthier lifestyles, and more preventive behaviors (4–6). Much of this research has focused on the health domain, while studies on social, economic, and emotional outcomes have largely been cross-sectional (2). Maintaining a sense that life is worthwhile may be particularly important at older ages when social and emotional ties often fragment, social engagement is reduced, and health problems may limit personal options.

Accordingly, we tested the association between the ONS rating of life being worthwhile and a range of social, economic, health, biomarker, and health-related behaviors in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), a representative population sample of men and women aged 50 and over living in England (7). Cross-sectional associations and longitudinal relationships between life being worthwhile and outcomes over a 4-y period were analyzed. We also explored the relationship between time use and having a meaningful life (8), so as to identify patterns of social, solitary, and productive activities over the day.

Results

We analyzed data from 7,304 participants (3,250 men and 4,054 women) in wave 6 (2012) of ELSA. Ages ranged from 50 to over 90 y (mean 67.21, SD 9.11). Worthwhile ratings averaged 7.41 (SD 2.24, range 0–10) and showed a curvilinear association with age (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Ratings of life being worthwhile were slightly higher in women than men (means 7.46 vs. 7.35) and were positively associated with educational attainment and socioeconomic status (SES) (P < 0.001; see SI Appendix, Table S1 for details).

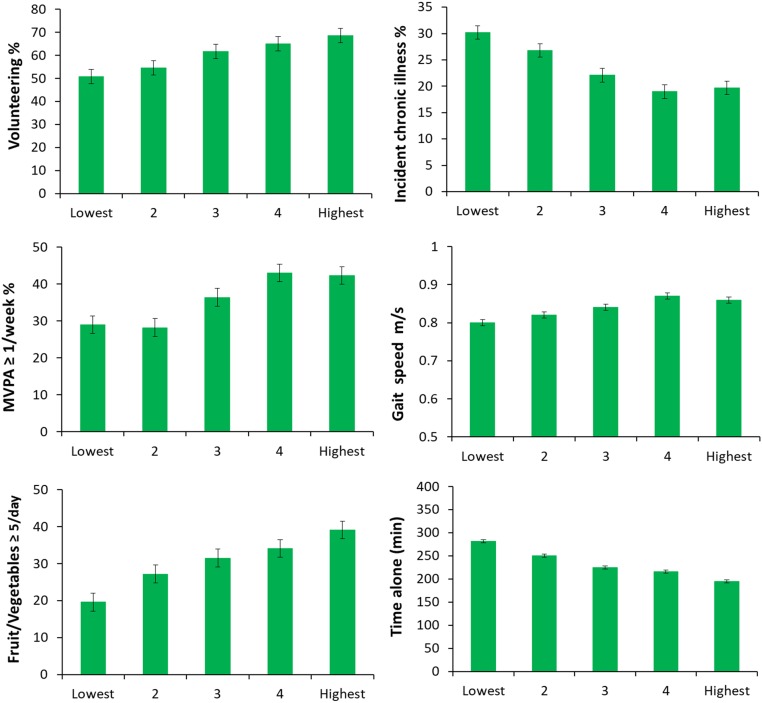

Results from cross-sectional linear and logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment, and SES are detailed in Table 1, and results from longitudinal regression analyses are given in Table 2. Key longitudinal findings are illustrated in Fig. 1 by dividing worthwhile ratings into five categories (0–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, 9–10) and computing covariate-adjusted percentages or means. Complete figures for all variables are presented in SI Appendix. Sample sizes differed across outcomes because of missing data and method of data collection (e.g., blood draws), as detailed in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Table 1.

Living a worthwhile life: Cross-sectional associations with social, economic, health, and time use measures

| Factor | OR | β | 95% CI | SE | P | E (CI) |

| Social variables | ||||||

| Married (%) | 1.16 | 1.14–1.19 | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.54) | ||

| Living alone (%) | 0.87 | 0.85–0.89 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.5) | ||

| Close relationships (n) | 0.242 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 2.47 (2.34) | ||

| Contact with friends ≥ 1/wk (%) | 1.13 | 1.10–1.15 | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.28) | ||

| Organizations (n) | 0.140 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.79) | ||

| Volunteer ≥ monthly (%) | 1.15 | 1.12–1.18 | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.31) | ||

| Loneliness | −0.427 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 3.77 (3.59) | ||

| Cultural activity ≥ every few months (%) | 1.11 | 1.09–1.14 | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.4) | ||

| Economic variables | ||||||

| Wealth highest tertile (%) | 1.11 | 1.08–1.14 | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.24) | ||

| Income highest tertile (%) | 1.10 | 1.07–1.13 | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.22) | ||

| Paid employment (%) | 1.12 | 1.08–1.15 | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.24) | ||

| Health variables | ||||||

| Poor/fair self-rated health (%) | 0.79 | 0.77–0.81 | <0.001 | 1.85 (1.77) | ||

| Limiting longstanding illness (%) | 0.83 | 0.81–0.85 | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.39) | ||

| Chronic disease (%) | 0.93 | 0.91–0.95 | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.19) | ||

| Depressive symptoms (%) | 0.65 | 0.63–0.67 | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.74) | ||

| Impaired ADL (%) | 0.83 | 0.81–0.85 | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.39) | ||

| Impaired IADL (%) | 0.80 | 0.78–0.82 | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.44) | ||

| Chronic pain (%) | 0.87 | 0.85–0.89 | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.31) | ||

| Biomarkers and physical capability | ||||||

| Hand-grip: men | 0.072 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.37) | ||

| Hand-grip : women | 0.078 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.40) | ||

| Obesity (%) | 0.95 | 0.93–0.97 | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.14) | ||

| Central obesity (%) | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.003 | 1.14 (1.08) | ||

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.121 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.67) | ||

| Vitamin D (nmol/L) | 0.093 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.51) | ||

| C-reactive protein ≥3 mg/L | 0.95 | 0.92–0.98 | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.16) | ||

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | −0.042 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 1.36 (1.21) | ||

| HDL-cholesterol below threshold (%) | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.004 | 1.32 (1.16) | ||

| White cell count (109/L) | −0.086 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.46) | ||

| Health behavior | ||||||

| MVPA ≥1/wk (%) | 1.16 | 1.14–1.19 | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.34) | ||

| Sedentary behavior (%) | 0.79 | 0.75–0.82 | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.44) | ||

| Fruit and vegetables ≥ 5/d (%) | 1.14 | 1.11–1.16 | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.29) | ||

| Alcohol (units/week) | −0.004 | 0.011 | 0.70 | 1.11 (1.00) | ||

| Sleep rating good/very good (%) | 1.20 | 1.17–1.23 | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.38) | ||

| Smoking (%) | 0.92 | 0.89–0.95 | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.28) | ||

| Time use yesterday | ||||||

| Time with friends (min) | 0.089 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.49) | ||

| Time alone (min) | −0.181 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 2.12 (2.00) | ||

| Time TV (min) | −0.093 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.56) | ||

| Time walk/exercise (min) | 0.115 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.64) | ||

| Time work/volunteer (min) | 0.035 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.16) | ||

Adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment, and social class. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental ADL; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; MVPA = moderate/vigorous physical activity; TV = television.

Table 2.

Living a worthwhile life: Longitudinal associations with social, economic, health, and time use over 4 y

| Factor | OR | β | 95% CI | SE | P | E (CI) |

| Social variables | ||||||

| Divorcea (%) | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.39) | ||

| Living aloneb (%) | 0.92 | 0.87–0.97 | 0.002 | 1.39 (1.21) | ||

| Close relationshipsc (n) | 0.082 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.46) | ||

| Contact with friends ≥ 1/wkd (%) | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | 0.017 | 1.2 (1.08) | ||

| Organizationse (n) | 0.033 | 0.010 | 0.002 | 1.31 (1.16) | ||

| Volunteer ≥ monthlyf (%) | 1.10 | 1.04–1.16 | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.24) | ||

| Loneliness ratingg | −0.097 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.67 (1.53) | ||

| Cultural activity ≥ every few monthsh (%) | 1.07 | 1.02–1.12 | 0.007 | 1.34 (1.16) | ||

| Economic variables | ||||||

| Wealth highest tertilei (%) | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.015 | 1.25 (1.14) | ||

| Income highest tertilej (%) | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.070 | 1.14 (1.0) | ||

| Paid employmentk (%) | 1.03 | 0.98–1.09 | 0.25 | 1.14 (1.0) | ||

| Health variables | ||||||

| Poor/fair self-rated healthl (%) | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.21) | ||

| Limiting longstanding illnessm (%) | 0.92 | 0.90–0.95 | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.19) | ||

| Chronic diseasen (%) | 0.94 | 0.91–0.97 | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.14) | ||

| Depressive symptomso (%) | 0.81 | 0.77–0.85 | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.39) | ||

| Impaired ADLp (%) | 0.86 | 0.83–0.90 | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.29) | ||

| Impaired IADLq (%) | 0.86 | 0.82–0.89 | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.31) | ||

| Chronic painr (%) | 0.94 | 0.90–0.98 | 0.002 | 1.21 (1.11) | ||

| Obesitys (%) | 0.94 | 0.90–0.98 | 0.007 | 1.21 (1.11) | ||

| Gait speedt (m/s) | 0.044 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.24) | ||

| Health behavior | ||||||

| MVPA ≥1/wku (%) | 1.11 | 1.06–1.15 | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.2) | ||

| Sedentary behaviorv (%) | 0.84 | 0.80–0.88 | <0.001 | 1.67 (1.53) | ||

| Fruit and vegetables ≥ 5/dw (%) | 1.09 | 1.04–1.13 | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.16) | ||

| Alcoholx (units/week) | 0.036 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 1.34 (1.21) | ||

| Sleep rating good/very goody (%) | 1.13 | 1.09–1.16 | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.26) | ||

| Smokingz (%) | 1.02 | 0.95–1.10 | 0.54 | 1.16 (1.0) | ||

| Time use yesterdayaa | ||||||

| Time with friends (min) | 0.034 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 1.31 (1.16) | ||

| Time alone (min) | −0.054 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.32) | ||

| Time TV (min) | −0.046 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.25) | ||

| Time walk/exercise (min) | 0.043 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.21) | ||

| Time work/volunteer (min) | 0.028 | 0.012 | 0.019 | 1.28 (1.11) | ||

Adjusted for age, sex, educational attainment and social class. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; MVPA = moderate/vigorous physical activity; TV = television.

Divorce among those married in 2012.

Living alone among those who were not living alone in 2012.

Adjusting for close relationships in 2012.

Among people without weekly contact in 2012.

Adjusting for organizational membership in 2012.

Continuing volunteering among people who volunteered in 2012.

Adjusting for loneliness in 2012.

Among people who were not culturally active in 2012.

Adjusting for wealth in 2012.

Adjusting for income in 2012.

Among people employed in 2012.

Adjusting for self-rated health in 2012.

Adjusting for limiting illness in 2012.

Incidence of chronic disease since 2012.

Adjusting for depression in 2012.

Incidence of impaired ADLs.

Incidence of impaired IADLs.

Incidence of chronic pain among people with no chronic pain in 2012.

Adjusting for obesity in 2012.

Adjusting for gait speed in 2012.

Among people inactive in 2012.

Among people not sedentary in 2012.

Among people not eating ≥5 fruit/vegetables per day on 2012.

Adjusting for alcohol in 2012.

Adjusting for sleep quality in 2012.

Adjusting for smoking in 2012.

aaTime use reassessed in 2014, analyses adjusted for time use in 2012.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative associations between worthwhile ratings [divided into five categories from lowest (0–2) to highest (9, 10)] and outcomes 4 y, adjusted for age, sex, education, and SES and for baseline values as detailed in Table 2. Error bars are SEs.

Social Variables.

Higher worthwhile ratings were associated with an increased likelihood of being married/having a partner, reduced likelihood of living alone, having a greater number of close relationships, and more frequent contact with friends (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). For example, 73.1% of participants with ratings of 9 or 10 had contact with friends at least on a weekly basis, declining to 47.1% of those with ratings of 0–2. Higher worthwhile ratings were also associated with belonging to a greater number of organizations such as social clubs, gyms, and churches, an increased probability of volunteering on a regular basis, and greatly reduced loneliness. Cultural activity, assessed in terms of going to museums, art galleries, concerts, and theaters at least every few months, was also more common among respondents with higher ratings of life being worthwhile.

Worthwhile ratings at baseline also predicted social outcomes 4 y later, in wave 8 of ELSA (2016), independently of baseline social measures (Table 2). Although few couples divorced over this time period, the risk of divorce was lower among those with higher worthwhile ratings at baseline (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Similarly, the risk of living alone in 2016 among those who were not living alone at baseline was inversely associated with worthwhile ratings. Number of close relationships in 2016 was positively associated with worthwhile ratings independently of relationships at baseline, while people without weekly contact with friends were more likely to start this by 2016 if their baseline worthwhile ratings were higher. The number of organizations to which a person belonged continued to be higher on follow-up, adjusting for baseline levels, and loneliness in 2016 remained lower in those with higher baseline worthwhile ratings. Interestingly, continuing to volunteer was predicted by baseline worthwhile ratings, and there was a 7% increase in the odds of initiating cultural activity for every point increase in worthwhile rating among individuals who were not culturally active at baseline.

Economic Variables.

We analyzed three indicators of prosperity and economic activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Leading a worthwhile life was associated with an 11% increased odds of having wealth in the top tertile (highest third of the wealth distribution) and 10% increased odds of income in the top tertile, adjusting for age, sex, education, and SES. Similar results emerged when wealth and income were modeled as continuous variables. People with higher worthwhile ratings were also more likely to be in paid employment; when these analyses were repeated on people aged 65 or younger, the same pattern emerged, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.13 [95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.09–1.17, P < 0.001]. Longitudinally, worthwhile ratings at baseline predicted wealth 4 y later, after taking baseline wealth into account (Table 2).

Health Variables, Biomarkers, and Physical Capability.

Worthwhile ratings were consistently related to better self-rated health, less limiting longstanding illness, less chronic disease (coronary disease, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, cancer, and chronic lung disease), and a lower likelihood of impaired activities of daily living (ADLs, such as difficulty bathing or showering), instrumental ADLs (e.g., difficulty managing money), and less chronic pain (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). For instance, 56.6% of respondents with ratings of 0–2 were in fair or poor health compared with 17.9% of those with ratings of 9 or 10. The associations with depressive symptoms were particularly pronounced, with a 35% reduced odds of having depressive symptoms above threshold per unit increase in worthwhile rating. These differences were supported by associations with biomarkers and objective indices of physical capability. Higher worthwhile ratings were significantly related to stronger hand grip, less objectively measured obesity and central adiposity, faster gait speed, lower plasma C-reactive protein and fibrinogen concentrations, lower white blood cell counts, higher vitamin D concentration, and better lipid profiles (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8). Baseline worthwhile ratings were also inversely associated with self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness 4 y later, adjusting for baseline levels as well as other covariates (Table 2). The incidence of new chronic disease was reduced among people with higher worthwhile ratings, as was the incidence of impaired ADLs among respondents who did not report impairment at baseline. New cases of depressive symptoms and new cases of moderate or severe chronic pain were significantly less common (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Blood was obtained from only a subset of participants, and grip strength was not measured in 2016, so these variables have not been analyzed longitudinally. However, objectively measured obesity on follow-up was inversely associated with worthwhile ratings at baseline, while gait speed was faster in those with higher worthwhile ratings after adjustment for baseline gait speed.

Health-Related Behaviors.

We tested associations between worthwhile ratings and several health-related behaviors (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Respondents with higher worthwhile ratings were more likely to report moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) at least weekly and were less likely to be sedentary. They were also more likely to eat at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day (as recommended in UK health guidelines). People with higher worthwhile ratings were more likely to rate their sleep as good or very good and were less likely to smoke. At 4 y follow-up, the associations with health behaviors persisted, and worthwhile ratings predicted new healthy changes (Table 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). There was an 11% increase in the odds of taking up MVPA among those who were not active at baseline and a lower risk of becoming sedentary. People with higher worthwhile ratings who were not eating at least five portions of fruit and vegetables at baseline were more likely to do so on follow-up, and worthwhile ratings predicted sustained good sleep. A positive association between worthwhile ratings and alcohol consumption emerged at follow-up, but there was no relationship with smoking after baseline smoking status had been taken into account.

Time Use.

Worthwhile ratings were positively associated with time spent with friends or family on the previous day, time spent walking or exercising, and time spent working or volunteering, after adjustment for covariates (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Conversely, worthwhile ratings were negatively related to time spent alone and time watching television (TV). For instance, people with low worthwhile ratings spent twice as much time alone on average than those with high worthwhile ratings. Time use was not reassessed in 2016, but it was measured in wave 7 (2014) of ELSA. Consequently, longitudinal analyses were conducted over a 2 y period. Higher worthwhile ratings were positively related to time spent with friends, walking/exercising, and working/volunteering and negatively related to time spent alone and watching TV (Table 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S13). These associations adjusted for baseline time use, so indicate that worthwhile ratings predict time spent in different activities in the future.

Sensitivity Analyses.

Differences in prosperity or in depressive mood might underlie the apparent associations between life being worthwhile and other measures. We reasoned that if this was the explanation, associations between worthwhile ratings and other measures would be eliminated or greatly reduced if these factors were included as covariates. Results (summarized in SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6) indicate that the large majority of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations remained significant, with only the strength of some associations slightly reduced. A second set of sensitivity analyses controlled for levels of outcomes before the assessment of worthwhile ratings, involving a uniform set of covariates across outcomes as advised by VanderWeele et al. (9). We therefore included as covariates measures of marital status, wealth, self-rated health, depressive symptoms, and smoking obtained in 2010, 2 y before worthwhile ratings were assessed. The results (shown in SI Appendix, Tables S7 and S8) indicate that 33 of the 38 cross-sectional associations remained robust, as did 16 of 32 longitudinal findings under these stringent conditions. The sample size was reduced because 663 individuals joined the study in 2012, and this may partly account for these results.

Discussion

Meaning of life is a complex concept involving notions of life being comprehensible and coherent, having purpose and direction, as well as having significance and being worth living (10). The sense of life being worthwhile is a component of eudemonia (10). It is also correlated with hedonic well-being (feelings of joy or sadness) and with evaluative well-being (life satisfaction), and these facets together contribute to overall subjective well-being (11). Our analyses indicate that ratings of doing worthwhile things among older people show associations with a wide spectrum of social, economic, health, biological, and behavioral factors both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Analyses controlled for a number of time-invariant factors that potentially impinge on these outcomes, including age, sex, educational background and SES. Sensitivity analyses showed that the associations were not driven by economic resources or negative emotional states (operationalized as depressive symptoms). The E value is an indicator of the minimum strength of association that an unmeasured confounder would need to fully explain away an association. E-values were relatively modest, which could suggest that further inclusion of confounders would lead to the attenuation of results (12). Additionally, we followed recent recommendations for outcome-wide studies in including a range of preexposure variables in sensitivity analyses (9).

Cross-sectionally, worthwhile ratings were associated with stronger personal relationships (marriage, number of close relationships, regular contact with friends) and broader social engagement (involvement in organizations, cultural activity, volunteering), while living alone and loneliness were related to lower worthwhile ratings. Longitudinally, it has been shown that social, cultural, and volunteer engagement predict purpose in life (13, 14). In these analyses, we found the reverse: worthwhile ratings predict greater contact with friends, a lower likelihood of living alone, greater cultural engagement, and a greater likelihood of persistent volunteering over 4 y. The feeling that one is doing worthwhile things in life therefore appears not only to be the product of social relationships and activities but also to contribute to future personal relationships and prosocial outcomes.

We found a positive association between worthwhile ratings and wealth and income, and a longitudinal relationship with future wealth over 4 y that was independent of current wealth. Since these associations were independent of occupational prestige and education, they do not merely reflect SES effects but distinct processes related to economic prosperity. An analysis of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study showed that sense of purpose predicts greater income and net wealth independently of covariates (15). The present results extend these observations into older ages.

The analyses of health variables indicate that the sense of doing worthwhile things in life is related to healthier profiles in terms of better self-rated health, less limiting illness and chronic disease, fewer depressive symptoms, less disability, and less chronic pain. Worthwhile ratings also predicted less incidence of chronic disease, depressive symptoms, and the development of disability and chronic pain over 4 y. We were able to corroborate these associations with analyses of objective measures of physical function, finding negative cross-sectional associations with obesity and waist circumference as well as longitudinal associations with obesity (waist circumference was only measured cross-sectionally). We also identified cross-sectional associations with upper body strength and longitudinal relationships with gait speed. These effects mesh with our results concerning the development of disability and physical activity and sedentary behavior, implicating a meaningful life in the maintenance of physical capability and activities at older ages. Not only are these important facets of sustained healthy life, they are also relevant to reduced risk of premature mortality (16).

The biomarker panel included three indicators of inflammation: C-reactive protein, plasma fibrinogen, and white blood cell count, all of which showed marked inverse associations with worthwhile ratings. Purpose in life has previously been associated with lower levels of single inflammatory markers (17), a finding extended in our study to include further measures known to predict future cardiovascular disease, less healthy aging, poorer mental health, and premature mortality (18, 19). Additionally, we found associations with higher vitamin D concentration, which has been linked with a range of health outcomes, while the inverse relationship with HDL-cholesterol is relevant to reduced cardiovascular disease risk. In combination, the objective biomarker data document a generally favorable profile of biological risk among people who feel their activities are worthwhile.

The health of older people with higher worthwhile ratings is also likely sustained by health-related behaviors such as fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, good sleep and not smoking. Worthwhile ratings predicted future increases in fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, and sustained sleep quality over the follow-up period independently of baseline levels, extending previous findings linking health behaviors with broader dimensions of subjective well-being (11). The alcohol results are harder to interpret, since worthwhile ratings were associated with an increase in alcohol consumption over time but not with baseline levels. However, the relationship between alcohol consumption and well-being may be curvilinear, with both abstinence and high levels associated with poorer mental health (20). The increases in consumption seen here may also reflect changes from very low to moderate levels of intake.

The associations we observed between worthwhile ratings and time use support our findings with broader social and behavioral measures. Worthwhile ratings were inversely associated not only with loneliness and living alone, but also with time spent alone on the previous day; a similar pattern has been described in the Health and Retirement Study (21). The observation that people with higher worthwhile ratings spent more time walking or exercising is consistent with the physical activity results. In other studies of time use, work and volunteering emerge as among the most rewarding activities in population samples (8), and this is endorsed by the associations between time spent in these activities and worthwhile ratings.

There was considerable variation in the strength of associations between worthwhile ratings and other variables. Both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, the strongest effects related to emotional well-being (depressive symptoms, loneliness), disability (ADLs), health behaviors (physical activity, sleep), and social function (close relationships, marriage). Notably, these associations cut across several different domains, with no single area appearing to predominate. This attests to the broad significance of the feelings that the things we do in life are worthwhile.

This is an observational study, so causal conclusions cannot be drawn, and unmeasured confounders may be relevant. Relationships are likely to be bidirectional, but the fact that worthwhile ratings predict future levels of such a wide range of outcomes independently of baseline values suggests that living a meaningful life may contribute to future health and optimal aging. In the context of this broad population study, we were only able to address rather general factors relevant to the sense that the things we do in life are worthwhile, and idiosyncratic factors will be relevant to each individual. Worthwhile activities in later life may center around maintaining harmonious family relationships, working toward goals in hobbies, the achievements of a favorite sports team, communing with nature, religious or spiritual faith, making money, intellectual accomplishment, satisfaction with work, stimulating travel, or other experiences. However, whatever the source, our findings suggest that engaging in activities perceived to be worthwhile has wide ramifications across many domains of human experience at older ages. This simple measure of life being worthwhile has been implemented in a number of national surveys in the United Kingdom, including the Annual Population Survey, the Wealth and Assets Survey, and the National Crime Survey. Wider adoption in other national and international surveys would provide important policy-relevant evidence.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Measures.

Data were analyzed from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), a nationally representative longitudinal panel study of English adults aged 50 and older (7). See SI Appendix for details. The study was approved through the National Research Ethics Service, and all participants provided informed consent. Life being worthwhile was assessed through answers to the question “to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?” with responses from 0 = not at all to 10 = very. Covariates, social, economic, health, biomarkers and health behaviors are detailed in SI Appendix. We measured time use with an adaptation of the Day Reconstruction Method devised for the Health and Retirement Study (22), asking about the amount of time spent on selected activities over the previous day.

Statistical Analysis.

Associations with social, economic, health, and biological factors were analyzed using logistic regression for binary outcomes and ordinary least squares regression for continuous outcomes, with worthwhile ratings being modeled as a continuous variable. We included age, sex, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status (SES) defined by occupational standing as covariates. We also computed E-values: indicators of how robust findings are to potential unmeasured confounding (12).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing is administered by a team of researchers based at the University College London, NatCen Social Research, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and the University of Manchester. Funding is provided by National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG017644 and by a consortium of UK government departments coordinated by Wellcome Trust Award 205407/Z/16/Z.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data in this paper have been deposited with the UK Data Service, www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/ (accession no. GN33368).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1814723116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.VanderWeele TJ. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:8148–8156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702996114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinquart M. Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: A meta-analysis. Ageing Int. 2002;27:90–114. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office for National Statistics 2018 Well-being. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing. Accessed August 13, 2018.

- 4.Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16331–16336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1093–1102. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2016;78:122–133. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steptoe A, Breeze E, Banks J, Nazroo J. Cohort profile: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–1648. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White MP, Dolan P. Accounting for the richness of daily activities. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:1000–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanderWeele TJ, Mathur MB, Chen Y. 2018 Outcome-wide longitudinal designs for causal inference: A new template for empirical studies. Available at https://arXiv.org/abs/1810.10164. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- 10.Heintzelman SJ, King LA. Life is pretty meaningful. Am Psychol. 2014;69:561–574. doi: 10.1037/a0035049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steptoe A. Happiness and health. Annu Rev Public Health, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: Introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:268–274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams KB, Leibbrandt S, Moon H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011;31:683–712. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:S258–S264. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill PL, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Burrow AL. The value of a purposeful life: Sense of purpose predicts greater income and net worth. J Res Pers. 2016;65:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper R, Strand BH, Hardy R, Patel KV, Kuh D. Physical capability in mid-life and survival over 13 years of follow-up: British birth cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g2219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman EM, Hayney M, Love GD, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Plasma interleukin-6 and soluble IL-6 receptors are associated with psychological well-being in aging women. Health Psychol. 2007;26:305–313. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lassale C, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. February 15, 2018. Association of 10-year C-reactive protein trajectories with markers of healthy aging: Findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beydoun MA, et al. White blood cell inflammatory markers are associated with depressive symptoms in a longitudinal study of urban adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e895. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caldwell TM, et al. Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97:583–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Queen TL, Stawski RS, Ryan LH, Smith J. Loneliness in a day: Activity engagement, time alone, and experienced emotions. Psychol Aging. 2014;29:297–305. doi: 10.1037/a0036889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J, Ryan L, Fisher GG, Sonnega A, Weir D. Health and Retirement Study 2017. Psychosocial and lifestyle questionnaire 2006-2016: Documentation report Core section LB (Inst for Soc Res, Univ of Mich, Ann Arbor, MI)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.