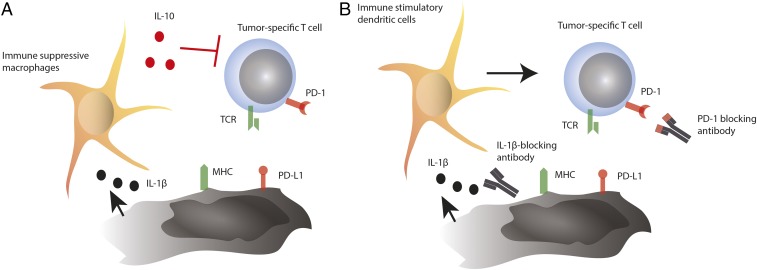

In PNAS, Kaplanov et al. (1) report on how IL-1β orchestrates recruitment of immunosuppressive monocytes and their polarization in IL-10–producing macrophages during tumor development. This mechanism consequently inhibits and limits CD8+ T cell-driven immune responses and enables tumor outgrowth. Therapeutic blockade of IL-1β and inhibition of monocyte recruitment synergized and enabled full T cell activity in combination with the blockade of the T cell inhibitory molecule, programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) (Fig. 1). As a result, this combination treatment mediated strong therapeutic benefit in a murine model of breast cancer.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the mechanism proposed in the study by Kaplanov et al. (1). (A) As a mechanism of cancer progression, tumor cells induce IL-1β production in the tumor milieu, which recruits and polarizes immunosuppressive macrophages. These macrophages suppress T cell activity via IL-10. (B) Blockade of IL-1β suppresses polarization and recruitment of suppressive myeloid cells, allowing the recruitment of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. PD-1 blockade then reinvigorates T cell responses and tumor reactivity for optimal antitumor activity. TCR, T cell receptor.

A significant body of evidence indicates that IL-1β is an important factor driving cancer progression and immune suppression through a plethora of mechanisms both on the tumor cell and on stromal and immune cells (2). However, until recently, clinical use of IL-1β–neutralizing agents has not been widely tested and the clinical utility reported was limited (3, 4). Potential caveats included either the short half-life of its commercial soluble antagonist (anakinra) or difficulties in identifying both a suitable indication and an adequate setting. In 2017, the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) trial, whose primary end point was to evaluate the use of IL-1β–neutralizing antibody for prevention of cardiovascular events in a high-risk population, reported the impact on cancer incidence (5). This was the largest study ever conducted in any indication with an IL-1β antagonist. Surprisingly, the trial reported a reduced incidence of lung cancer in patients treated with IL-1β–neutralizing antibody. While it is tempting to speculate that blocking IL-1β would prevent tumor development, the comparably short observation period as opposed to a lifelong exposure to carcinogens required for lung cancer development largely rules out this hypothesis (6). We and others have speculated on diverse known and unknown mechanisms related to downstream functions of IL-1β and cancer progression, including a direct impact on the cancer cell as well as the induction of cancer drivers, including IL-22 (7–10).

Intriguingly, the patient population of the CANTOS trial encompasses a large collective of current and past smokers who happen to be at particular risk for lung cancers, most of which are typically squamous cell lung cancer and, to some degree, adenocarcinomas. Smoke-induced lung cancer is known to be highly immunogenic and a disease that can be controlled by T cells (11). Along these lines, T cell reinvigoration through PD-1 or PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade is an approved treatment for lung cancer, thus indicating that proper T cell function will mediate therapeutic benefit (12).

The data from Kaplanov et al. (1), though from murine models only, prompts us to revisit such considerations. Adequate blockade of IL-1β could thus have prevented recruitment and polarization of immunosuppressive myeloid cells and thereby enabled T cell activity in a highly immunogenic disease at an early stage. Either cancer-specific T cells could have been generated or those already present could have exerted their activity in the absence of suppression by macrophages. Eventually, this could have eradicated the nascent lung cancer or pushed it back below any limit of detection currently available.

One could also further speculate that combination with approved compounds such as PD-1– or PD-L1–neutralizing agents could recapitulate what has been seen in murine models and synergize for therapeutic benefit to a level not previously conceivable. Especially in an early-stage setting, this might be particularly promising in light of neoadjuvant anti–PD-1 antibody data reported in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (13). It is tempting to envision what the responses would have been had the patients additionally been treated with IL-1β blockade. Owing to the high need of this patient population who are at high risk of relapsing despite surgery and other treatments, inducing a strong and potentially lasting immune response seems to bear high promise.

In any case, it is also important to keep in mind that the present study by Kaplanov et al. (1), although very sound and relevant to the field, demonstrated its finding in only one murine breast cancer model. Importantly, the present model has a peculiar immunology with a huge myeloid component that is heavily immunosuppressive and progresses with the disease (14). Accordingly, it is unclear how the proposed strategy would perform in an environment that is either not dependent or less dependent on myeloid cells. Similarly, the inhibition of inflammation through IL-1β blockade and the activation of T cells through PD-1 blockade require both preexisting T cell immunity and inflammation in the first place. Given that a significant proportion of cancer, be it from lung or mammary or other origin, is regarded as immunologically cold (with little or no immunological infiltrate), it is unclear how the strategy would perform here. Owing to the plethora of potential IL-1β–driven mechanisms, this combination treatment could also surprise with yet-unexpected mechanisms. It will be important to see how well these results can be recapitulated across models and entities to prompt more thorough clinical investigations. However, with the different agents required for clinical testing and implementation, namely anti–IL-1β antibody and anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies, such an endeavor seems within reach. It needs to be considered that each agent comes with a side-effect profile of its own and there is a risk that toxicities might exacerbate each other. Future work will need to thoroughly investigate this aspect.

Acknowledgments

S.K. is supported by grants from the international doctoral program i-Target funded by Elite Network Bavaria; the Melanoma Research Alliance (Grants N269626 and 409510); the Marie-Sklodowska-Curie Training Network for the Immunotherapy of Cancer funded by the H2020 program of the European Union; the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung; the German Cancer Aid; the Ernst-Jung-Stiftung; the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung VIP+ Grant ONKATTRACT; and the European Research Council (Starting Grant 756017).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: S.K. is the inventor of several patent applications in the field of immunooncology unrelated to the work commented on and receives research funding from TCR2 Inc.

See companion article on page 1361.

References

- 1.Kaplanov I, et al. Blocking IL-1β reverses the immunosuppression in mouse breast cancer and synergizes with anti–PD-1 for tumor abrogation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:1361–1369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812266115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinarello CA. Why not treat human cancer with interleukin-1 blockade? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:317–329. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lust JA, et al. Induction of a chronic disease state in patients with smoldering or indolent multiple myeloma by targeting interleukin 1beta-induced interleukin 6 production and the myeloma proliferative component. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:114–122. doi: 10.4065/84.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JW. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:633–652. doi: 10.1038/nrd3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridker PM, et al. CANTOS Trial Group Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: Exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller YE. Pathogenesis of lung cancer: 100 year report. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:216–223. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0158OE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottschlich A, Endres S, Kobold S. Can we use interleukin-1β blockade for lung cancer treatment? Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7:S160–S164. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.03.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voigt C, et al. Cancer cells induce interleukin-22 production from memory CD4+ T cells via interleukin-1 to promote tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:12994–12999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705165114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crossman D, Rothman AMK. Interleukin-1 beta inhibition with canakinumab and reducing lung cancer-subset analysis of the canakinumab anti-inflammatory thrombosis outcome study trial (CANTOS) J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:S3084–S3087. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.07.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markota A, Endres S, Kobold S. Targeting interleukin-22 for cancer therapy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:2012–2015. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1461300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carbone DP, Gandara DR, Antonia SJ, Zielinski C, Paz-Ares L. Non-small-cell lung cancer: Role of the immune system and potential for immunotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:974–984. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobold S, Krackhardt A, Schlösser H, Wolf D. [Immuno-Oncology: A brief overview] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2018;143:1006–1013. German. doi: 10.1055/a-0623-9147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forde PM, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1976–1986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DuPré SA, Redelman D, Hunter KW., Jr The mouse mammary carcinoma 4T1: Characterization of the cellular landscape of primary tumours and metastatic tumour foci. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88:351–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]