Abstract

Introduction

Emergency department (ED)-initiated palliative care has been shown to improve patient-centred outcomes in older adults with serious, life-limiting illnesses. However, the optimal modality for providing such interventions is unknown. This study aims to compare nurse-led telephonic case management to specialty outpatient palliative care for older adults with serious, life-limiting illness on: (1) quality of life in patients; (2) healthcare utilisation; (3) loneliness and symptom burden and (4) caregiver strain, caregiver quality of life and bereavement.

Methods and analysis

This is a protocol for a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel, two-arm randomised controlled trial in ED patients comparing two established models of palliative care: nurse-led telephonic case management and specialty, outpatient palliative care. We will enrol 1350 patients aged 50+ years and 675 of their caregivers across nine EDs. Eligible patients: (1) have advanced cancer (metastatic solid tumour) or end-stage organ failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, end-stage renal disease with glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/m2, or global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease stage III, IV or oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease); (2) speak English; (3) are scheduled for ED discharge or observation status; (4) reside locally; (5) have a working telephone and (6) are insured. Patients will be excluded if they: (1) have dementia; (2) have received hospice care or two or more palliative care visits in the last 6 months or (3) reside in a long-term care facility. We will use patient-level block randomisation, stratified by ED site and disease. Effectiveness will be compared by measuring the impact of each intervention on the specified outcomes. The primary outcome will measure change in patient quality of life.

Ethics and dissemination

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all study sites. Trial results will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

NCT03325985; Pre-results.

Keywords: palliative care, randomised controlled trial, older adults, advanced illness, comparative effectiveness, emergency department

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be a large, randomised controlled trial comparing the efficacy of two palliative care models; it will provide evidence on which to base emergency department-initiated palliative care interventions.

Subjects are recruited from geographically and contextually diverse settings across public hospitals, academic medical centres and community hospital affiliates nationwide.

To ensure a pragmatic, patient-oriented intervention, we incorporated feedback from patient and organisational stakeholders, as well as our clinical and research collaborators.

The lack of blinding of patients and clinicians delivering the interventions is an inherent limitation of the study design.

Introduction

Rationale

According to the World Health Organization, palliative care is ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.’ Palliative care can include hospice care, but is distinct from hospice in that it may be delivered throughout the time course of serious, life-limiting illness alongside life-prolonging, disease-model treatment.1

Multiple studies have shown that palliative care services improve patients’ symptoms and the quality of end-of-life care across a broad range of illnesses. Patients receiving palliative care services are often able to remain cared for and supported at home, leading to greater patient and family satisfaction and less prolonged grief and post-traumatic stress disorder among bereaved family members.2–7 Palliative care also lowers costs by reducing unnecessary hospitalisations, diagnostic and treatment interventions, and avoidable intensive and emergency department (ED) care.8–12 Randomised trials with palliative care interventions have demonstrated: (1) better quality of life and mood in patients with poor-prognosis cancer who received palliative care in addition to standard care and (2) improved symptom management and patient satisfaction.9 13 Patients with late-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and heart failure who were randomly assigned to in-home palliative care, as compared with usual care, reported greater satisfaction with care and were more likely to die at home.14

The ED serves as the healthcare safety net for the most vulnerable, including older adults, non-Hispanic blacks, the poor and those with Medicaid coverage.15 Notably, half of older Americans visit the ED in the last month of life, and patients with serious illness frequently visit the ED, making the ED a key decision point where providers establish the subsequent care trajectory.16–18 Palliative care interventions in the ED can both capture high-risk patients at a time of crisis and dramatically improve patient-centred outcomes.19 20

Case management palliative care programmes have been used in older adults with multiple chronic conditions and have demonstrated reductions in end of life healthcare utilisation and increased hospice utilisation.21–23 Many of these programmes have used nurse-led telephonic contact, which is less expensive and more accessible to seriously ill patients than outpatient palliative care encounters. However, there is little to no research comparing the effectiveness of the telephonic case management model to the more costly model of specialty, outpatient palliative care.

Therefore, this is a protocol for a large, multicentre, parallel, two-arm randomised controlled trial in ED patients comparing two established models of palliative care: nurse-led telephonic case management and specialty, outpatient palliative care. The current evidence base has critical gaps, notably failing to achieve statistical power in order to ‘report conclusive results’, ‘account for clustering’, ‘quantify the effects’ of palliative care and ‘address the generalisability of insights across settings’.24 25 We address these evidence gaps in our trial by evaluating palliative care in a variety of ED settings, using validated tools to quantify changes in our outcomes of interest, and performing rigorous power calculations based on our prior randomised controlled trial of palliative care in the ED.

Objectives

The aims of this study are to compare nurse-led telephonic case management to facilitated, outpatient specialty palliative care for older adults with serious, life-limiting illness on: (1) quality of life in patients, as measured by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G)26 from enrolment to 6 months; (2) healthcare utilisation (eg, ED revisits, hospital admissions, hospice use)27–30 at 12 months; (3) loneliness, as measured by the Three-Item Loneliness Scale31 32 and symptom burden, as measured by Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale Revised (ESAS-r)33 from enrolment to 6 months and (4) caregiver strain, as measured by the 12-item Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12),34 caregiver quality of life, as measured by the 10-item Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS-10)35 and bereavement, as measured by the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG)36 3 months after patient death.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

This is a pragmatic, two-arm, multisite randomised controlled trial of 1350 older adults (50+ years) with either poor-prognosis cancer or end-stage organ failure who will be recruited during an ED visit, along with 675 of their informal caregivers, to compare nurse-led telephonic case management to facilitated, outpatient specialty palliative care. Recruitment began in April 2018 and will continue through July 2021. All follow-up data collection is expected to be completed by August 2022. Randomisation will be at the patient level and will be stratified by ED site and disease (advanced cancer vs end-stage organ failure) to ensure a balance of patients randomised to each intervention at each site. We will use block randomisation with random block sizes of two, four and six at a ratio of 1:1 assignment to each group. A biostatistician will randomly preassign the expected number of study subjects to either intervention group at each site (150 patients at each of nine sites for a total of 1350 patients).

Setting

This trial will be conducted in the EDs of nine diverse sites, including large public hospitals, academic medical centres and smaller community hospitals in different regions across the country (see table 1).

Table 1.

ED characteristics and eligible adult patients with serious illness, by year

| Site | Location | Inpatient beds | Admissions | ED visits | Eligible*, no (% of ED visits) |

Discharged or Observed†, no (% of eligible) |

| New York University (NYU) School of Medicine | ||||||

| Perelman ED/Tisch Hospital | New York City, New York, USA | 718 | 38 045 | 60 096 | 9014 (15) | 2704 (30) |

| Bellevue Hospital Center ED | New York City, New York, USA | 827 | 29 793 | 122 389 | 11 015 (9) | 2203 (20) |

| NYU Hospital Brooklyn ED | Brooklyn, New York, USA | 450 | 24 748 | 68 060 | 8167 (12) | 2041 (25) |

| Brigham and Women’s/Dana Farber Cancer Institute | ||||||

| Brigham and Women’s ED | Boston, Massachusetts, USA | 757 | 19 091 | 62 000 | 9300 (15) | 2511 (27) |

| Beaumont | ||||||

| Royal Oak | Royal Oak, Michigan, USA | 1070 | 58 539 | 120 000 | 25 666 (21) | 3853 (15) |

| Troy | Troy, Michigan, USA | 520 | 33 759 | 79 000 | 17 434 (22) | 2151 (12) |

| Ohio State University | ||||||

| Wexner Medical Center | Columbus, Ohio, USA | 962 | 45 927 | 120 156 | 17 801 (15) | 8393 (47) |

| University of Florida (UF) | ||||||

| UF Shands | Gainesville, Florida, USA | 973 | 41 669 | 75 537 | 15 561 (21) | 5176 (33) |

| Yale University | ||||||

| Yale New Haven | New Haven, Connecticut, USA | 1576 | 54 412 | 141 422 | 11 828 (8) | 4408 (37) |

*ED-admissions by patients with ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes consistent with advanced cancer or end-stage organ failure.

†Patients who met criteria based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes who were discharged home from the ED or the observation unit.

ED, emergency department.

Prior to the start of patient recruitment, the principal investigator (PI) at each site notified all primary care providers and haematologists/oncologists in the health system via email of the study parameters in order to allow physicians to opt-out of routine participation by their patients. The site PI assumed that any primary care providers or haematologists/oncologists who did not opt out of participation were willing to have their eligible patients enrol.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Patients eligible for participation are English-speaking adults aged 50+ years with a serious, life-limiting condition. Qualifying conditions include advanced cancer (defined as a solid metastatic tumour meeting advanced cancer criteria; see online supplementary 1) and poor prognosis, end-stage organ failure (defined as New York Heart Association class III and IV heart failure,37 38 end-stage renal disease defined as glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/m2 or global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease stage III and IV or oxygen-dependent COPD defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 s <50% predicted or the modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale).39 Patients must be scheduled for ED discharge or observation status. Patients who are placed in observation overnight will still be eligible to participate the following morning. For sites with no observation unit, patients with an expected admission of two nights or less will be eligible. Patients must have health insurance, reside within the geographical area and have a working telephone. These inclusion criteria are designed to ensure that patient participants are able to engage in the intervention and follow-up procedures.

bmjopen-2018-025692supp001.pdf (756.5KB, pdf)

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude those patients with dementia identified in the electronic health records (EHRs), received hospice services or two or more palliative care visits in the last 6 months, or reside in a skilled nursing or assisted living facility or chronic care hospital. These exclusion criteria are in place to ensure effective engagement with the intervention and follow-up protocols. No specific genders or racial or ethnic origins will be excluded from this study. Children, pregnant patients and prisoners will not be recruited.

Caregiver criteria

English-speaking primary caregivers aged 18+ years who accompany eligible, enrolled patients will be eligible to participate. The caregiver must fulfil one of the following categories: (1) immediate or extended family member or (2) close friend who lives with the eligible patient full time. Caregivers must possess a working telephone and cannot be currently compensated for providing care to a patient if not a family member. The caregiver sample will exclude individuals <18 years old because the unique stresses a child caregiver experiences are outside of the scope of this study. No specific genders and racial and ethnic origins will be excluded from this study.

Recruitment

Research assistants (RAs) will check the ED and observation unit electronic track boards at each site at least two to three times a day to identify patients with previously defined qualifying conditions. The RAs will review patients’ EHRs to confirm inclusion criteria are met. This recruitment method will ensure the RAs only approach patients who are potentially eligible for the study.

RAs will then approach patients and conduct face-to-face interviews to confirm that patients meet all eligibility criteria. Once eligibility is established, RAs will discuss with patients the purpose, requirements and timeline of the study. For patients interested in enrolling for the study, RAs will then review the consent form with participants and obtain signed, informed consent (see online supplementaries 2 and 3).

After informed consent is signed, a baseline face-to-face survey will be conducted at bedside to document participants’ demographics and quality of life, loneliness and symptom burden.

After patient enrolment, RAs will assess accompanying caregivers and discuss their participation in the study. With each caregiver agreeing to participate, RAs will review the caregiver consent form, obtain signed, informed consent and conduct a baseline face-to-face survey.

Each patient and caregiver will be offered a US$40 gift card to participate with a repeated compensation of a US$20 gift card for completing each subsequent follow-up survey over the phone. Patients randomised to the outpatient arm will receive a US$25 gift card for each appointment attended during study enrolment.

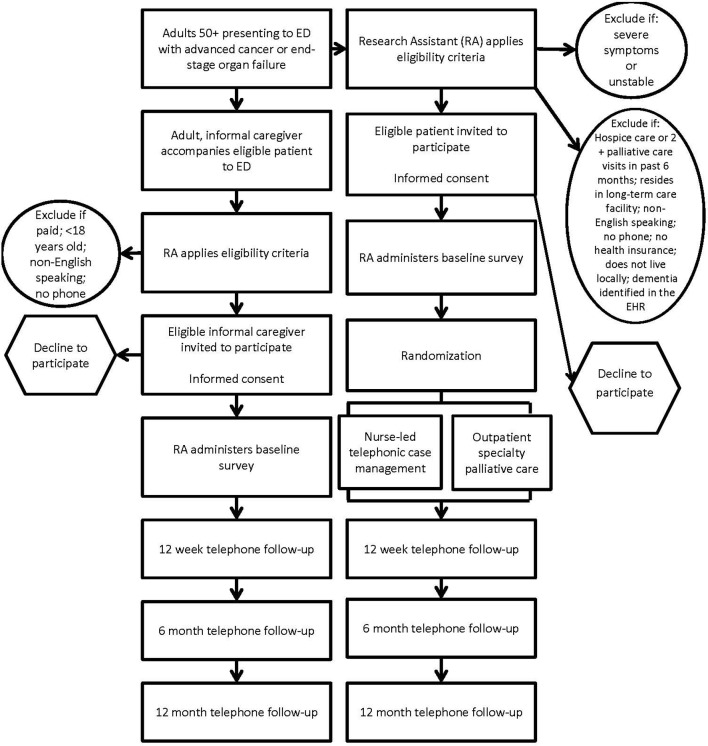

Randomisation and blinding

After a patient has enrolled in the study and completed the baseline interview, an automated notification will be sent to the project manager, who will initiate patient randomisation based on the previously generated allocation sequence. Depending on patient assignment, the project manager will relay the patient’s contact information to the telephonic nurses or outpatient palliative care clinic so that they can initiate the appropriate intervention. A list linking the patient name and group assignment will only be accessible to the project manager and data analyst; RAs and other staff involved in recruitment, follow-up and analysis will remain blinded to patient assignment. It is not feasible to blind study subjects or care providers to patient assignment. The unit of analysis will be the patient, and a blinded outcome assessment will occur for all patient and caregiver participants at 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. Please refer to figure 1 for the study overview diagram.

Figure 1.

Study overview diagram. ED, emergency department.

Treatment arms

Both treatment arms will include standardised assessments and referral for patients randomised to either group, as well as criteria for the timing and frequency of follow-up visits and phone calls. All care will address ongoing concerns within the eight domains of palliative care1: (1) structure and processes of care (eg, goals of care); (2) physical aspects of care (eg, pain); (3) psychological aspects of care (eg, depression); (4) social aspects of care (eg, caregiver burden); (5) spiritual aspects of care (eg, hopes and fears); (6) cultural aspects of care (eg, ritual); (7) care of the imminently dying (eg, prognosis) and (8) ethical and legal aspects of care (eg, advance directives).

Nurse-led telephonic case management arm

Nurse-led telephonic case management will be conducted at a central site located at the primary site, New York University School of Medicine (NYUSoM). A registered nurse with a Certified Hospice and Palliative Nurse certification will interact with patients via telephone and deliver quality care according to the eight domains of palliative care as described above. The nurse will contact the patient once a week, or more frequently according to patient needs, for a duration of 6 months.

Facilitated, outpatient care arm

Facilitated, outpatient specialty palliative care visits will take place face to face in the outpatient facilities at each participating clinical site. A physician or nurse practitioner board eligible or board certified in hospice and palliative medicine will also deliver care according to the eight domains of palliative care as outlined above. The patient will be scheduled to meet with the outpatient team once a month for a duration of 6 months.

Follow-up assessments

While receiving either intervention, all enrolled patients and caregivers will participate in follow-up assessments using the same questionnaires that were completed at baseline (FACT-G, Three-Item Loneliness Scale, ESAS-r, ZBI-12, PROMIS-10). RAs will complete follow-up assessments over the phone. For both caregivers and patients, follow-ups will take place 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after enrolment.

If patient death occurs during the course of the study, the caregiver will be asked additional questions about bereavement using the TRIG survey. This bereavement instrument is completed 3 months after patient death.

Outcome measures

Outcomes were specified ahead of time. Dependent and independent variables are collected by blinded RAs via face-to-face bedside interview or EHR at baseline prior to randomisation and over the phone at 12 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. Healthcare utilisation data, including ED revisits, inpatient days and hospice use, will be abstracted from the EHR and administrative data at 12 months. Independent and dependent variables are listed in online supplementaries 4 and 5, respectively.

The primary outcome is change in patient quality of life from enrolment to 6 months, as measured by the FACT-G. The FACT-G is a 27-item questionnaire assessing quality of life domains in physical, social, emotional and functional well-being.26 While it has been used extensively in oncology, it is validated and used as an assessment of chronic illness therapy in many other serious illnesses.40

Secondary outcomes in patients include healthcare utilisation (ED visits, hospital admissions and hospice use) from enrolment to 12 months; loneliness, as measured by change in the Three-Item Loneliness Scale from enrolment to 6 months; symptom burden, as measured by change in the ESAS-r from enrolment to 6 months and quality of life, as measured by the FACT-G, at 12 weeks and 12 months. Secondary outcomes in caregivers include caregiver physical and psychosocial distress, as measured by change in the ZBI-12 from enrolment to 6 months; caregiver quality of life, as measured by change in the PROMIS-10 from enrolment to 6 months and bereavement as measured by the TRIG at 3 months after patient death.

Adverse events

Numerous important medical events, such as hospitalisation and death, are expected due to the stage of patients’ illnesses and will be unrelated to the study. We do not expect any study-related serious adverse events.

Data collection and management

Data collection is performed by trained RAs at each study site, and data entry into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database is completed in a standardised fashion on tablets and computers. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.41

Statistical analysis

The primary effect of interest is the change in quality of life of patients with serious, life-limiting illness from baseline to 6 months as measured by the FACT-G. The effect size parameter will be estimated by comparing patients who receive telephonic palliative care with those who receive outpatient palliative care. Randomisation will be done at the site level and stratified by primary diagnosis. This ensures that each of the nine sites will have patients in both intervention arms, and patients with cancer will be randomised separately from those who have an organ failure diagnosis. To account for nesting in the data structure (patients nested in hospitals), we will use mixed effect multilevel linear model to estimate effect sizes. We anticipate two sources of variation. First, there will be regional (site) variation in the outcomes independent of the intervention; although the telephonic arm is centrally delivered, there may still be clustering at the site level. Second, there will be variation in how specialty, palliative care outpatient clinics deliver the clinic intervention arm, which will add an additional source of variation for this arm alone. We will adjust for cancer status to account for differences in outcomes for the patients with cancer and non-cancer in the study. If we conclude there is enough evidence that suggests there is an intervention effect (based on a t-test using α=0.05), we will use a second model to assess whether the treatment effect differs for patients with cancer and organ failure.

We will analyse the secondary outcomes using similar multilevel models. In one set of analyses, we will be investigating whether the intervention affects healthcare utilisation following the initial ED visit. These outcomes—subsequent ED visits (counts), inpatient days (counts) and hospice use (binary)—will require generalised linear mixed effect models; for the count models we will consider Poisson or negative binomial distributions, and for the binary outcome we will use logistic regression. In a second set of analyses, we will be measuring the intervention effects on additional quality of life measures—loneliness, symptom burden, caregiver strain, caregiver quality of life and bereavement—which are all continuous measures. For these analyses, we will use linear mixed effect models.

Sample size calculation

Simulation methods were used to estimate power based on the primary outcome, a change in quality of life from enrolment to 6 months as measured by the FACT-G. In the simulations, we incorporated the two sources of variability at the site level, as described in the statistical plan. We further assumed a drop-out rate of 15% due to death or drop-out, as we will recruit patients earlier in the course of their advanced illness when they are still well enough to be discharged home. With an effective sample size of 287 subjects in each comparison arm, we will achieve 100% power to detect an effect of nurse-led telephonic care given an overall effect of 4 points on the FACT-G, a clinically meaningful difference in quality of life. Moreover, this sample size will provide about 80% power to detect a difference in effect sizes between the groups given that the true difference is only 2 points.

Patient and public involvement

A study advisory committee was assembled of (1) patients with serious, life-limiting illness and their caregivers; (2) the chief medical executive of a large Medicare Advantage Plan; (3) community faculty from Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Division of Community Engagement; (4) patient advocates from stakeholder organisations (eg, American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, Equity Healthcare, Cambia Health); (5) representatives from Emergency Medicine and Palliative Care organisations (eg, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, Emergency Nurses Association) and (6) other content experts. These key stakeholders, who have a history of cofunding, copublication and collaboration, are involved in all stages of the research, including the development of appropriate comparators and outcomes of interest, the conduct and oversight of the study, and analysis and dissemination of the results.

Monitoring

The PI, in cooperation with the coinvestigators and the NYUSoM Institutional Review Board (IRB), will monitor the safety of the proposed project. We have created a data safety and monitoring plan and established formal monitoring procedures at each site to closely monitor participant safety, data quality and study progress. A data monitoring committee is not needed since the study is minimal risk.

Monitoring for protocol adherence will be performed monthly to ensure early identification of poor performance at individual sites and in the trial overall. Specific parameters to be monitored will include randomisation of ineligible subjects and treatment allocation errors. Our study protocol will continue to be informed by our patient and organisational stakeholders throughout its initiation.

Ethics and dissemination

Safety considerations

IRB approval was first obtained at NYUSoM, followed by approval from the other study sites (see online supplementary 6). To minimise research-associated risk and protect the confidentiality of participant data, all investigators and staff involved in this project have completed extensive courses and passed certifying examinations on the protection of human subjects in research through Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative training and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act certification.

Dissemination plan

Patient and organisational stakeholders will significantly contribute to the translation of the research findings into lay language. Additionally, our group has long-standing relationships with large, disease-based not-for-profit organisations and will work closely with these stakeholders to develop and activate their communications infrastructure to disseminate our results through social media, community-based outreach and local academic partners. Furthermore, the results of this study will be submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov, and peer-review publications will be coauthored by the research team.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the EMPallA Study Advisory Committee for their contributions to the development of our protocol.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: CRG: conception and design of study, drafting and critically revising the manuscript. DJS: acquisition of study data, drafting and critically revising the manuscript. AMS: acquisition of study data, drafting and critically revising the manuscript. JC: acquisition of study data, drafting and critically revising the manuscript. KSG: conception and design of study, drafting the manuscript. ‘The EMPallA Investigators’ development of the protocol and manuscript review. All authors approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was (partially) supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PLC-1609-36306) and a Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) grant (1T35AG050998-01) from the National Institute on Aging (Abigail Schmucker).

Disclaimer: All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: New York University School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Collaborators: The EMPallA Investigators: Ada L Rubin, Caroline Blaum, Lauren Southerland, Jeffrey M Caterino, Kei Ouchi, Marie-Carmelle Elie, Robert Swor, Karen Jubanyik, Susan E Cohen, Arum Kim, Joseph Lowy, Jennifer S Scherer, Nancy E Bael, Ellin Gafford, Joshua Lakin, Paige Barker, Angela Chmielewski, Jennifer Kapo, Audrey Tan, Abraham Brody, Rebecca Yamarik, Susan Salz, Stephen Ryan, Anne Kim, Mara Flannery, Isabel Castro, Nicole Tang, Michael Hill, Amelia Hargrove, Richard Tamirian, Rebecca Murray, Laura Stuecher, Nora Daut, Pamela Marsack, Jennifer Bonito, Marie Bakitas, Romilla Batra, Juanita Booker-Vaughns, Donna C Sadasivan, Garrett K Chan, J Nicholas Dionne-Odom, Patrick Dunn, Robert Galvin, Ernest A Hopkins III, Eric David Isaacs, Constance L Kizzie-Gillett, Margaret M Maguire, Neha Reddy Pidatala, Dawn Rosini, William K Vaughan, Sally Welsh, Pluscedia G Williams, Angela Young-Brinn

Contributor Information

The EMPallA Investigators:

Ada L Rubin, Caroline Blaum, Lauren Southerland, Jeffrey M Caterino, Kei Ouchi, Marie-Carmelle Elie, Robert Swor, Karen Jubanyik, Susan E Cohen, Arum Kim, Joseph Lowy, Jennifer S Scherer, Nancy E Bael, Ellin Gafford, Joshua Lakin, Paige Barker, Angela Chmielewski, Jennifer Kapo, Audrey Tan, Abraham Brody, Rebecca Yamarik, Susan Salz, Stephen Ryan, Anne Kim, Mara Flannery, Isabel Castro, Nicole Tang, Michael Hill, Amelia Hargrove, Richard Tamirian, Rebecca Murray, Laura Stuecher, Nora Daut, Pamela Marsack, Jennifer Bonito, Marie Bakitas, Romilla Batra, Juanita Booker-Vaughns, Donna C Sadasivan, Garrett K Chan, J Nicholas Dionne-Odom, Patrick Dunn, Robert Galvin, Ernest A Hopkins III, Eric David Isaacs, Constance L Kizzie-Gillett, Margaret M Maguire, Neha Reddy Pidatala, Dawn Rosini, William K Vaughan, Sally Welsh, Pluscedia G Williams, and Angela Young-Brinn

References

- 1. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Center to Advance Palliative Care Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association Last Acts Partnership National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med 2004;7:611–27. 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elsayem A, Swint K, Fisch MJ, et al. . Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2008–14. 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith TJ, Coyne P, Cassel B, et al. . A high-volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in-hospital end-of-life care costs. J Palliat Med 2003;6:699–705. 10.1089/109662103322515202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Higginson IJ, Finlay I, Goodwin DM, et al. . Do hospital-based palliative teams improve care for patients or families at the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:96–106. 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00406-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, et al. . Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:150–68. 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00599-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manfredi PL, Morrison RS, Morris J, et al. . Palliative care consultations: how do they impact the care of hospitalized patients? J Pain Symptom Manage 2000;20:166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casarett D, Johnson M, Smith D, et al. . The optimal delivery of palliative care: a national comparison of the outcomes of consultation teams vs inpatient units. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:649–55. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. . Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1783–90. 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. . Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–9. 10.1001/jama.2009.1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. . Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457–64. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. . Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–73. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. . Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2745–52. 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. . The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83–91. 10.1001/archinte.164.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. . Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993–1000. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gindi RM, Black LI, Cohen RA. Reasons for emergency room use among U.S. Adults aged 18-64: National Health Interview Survey, 2013 and 2014. National health statistics reports 2016;90:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. . Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff 2012;31:1277–85. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mayer DK, Travers D, Wyss A, et al. . Why do patients with cancer visit emergency departments? Results of a 2008 population study in North Carolina. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2683–8. 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barbera L, Taylor C, Dudgeon D. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life? CMAJ 2010;182:563–8. 10.1503/cmaj.091187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu FM, Newman JM, Lasher A, et al. . Effects of initiating palliative care consultation in the emergency department on inpatient length of stay. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1362–7. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. . Emergency Department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2016. (Published 16 Jan 2016). 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spettell CM, Rawlins WS, Krakauer R, et al. . A comprehensive case management program to improve palliative care. J Palliat Med 2009;12:827–32. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meier DE, Thar W, Jordan A, et al. . Integrating case management and palliative care. J Palliat Med 2004;7:119–34. 10.1089/109662104322737395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamarik R, Batra R, Matthews L. A health plan’s innovative telephonic case management model to provide palliative care (TH303). J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:329 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. . Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698–709. 10.1001/jama.299.14.1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. . Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:147–59. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. . The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leggett LE, Khadaroo RG, Holroyd-Leduc J, et al. . Measuring resource utilization: a systematic review of validated self-reported questionnaires. Medicine 2016;95:e2759 10.1097/MD.0000000000002759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Baker L, et al. . Evaluating the efficiency of california providers in caring for patients with chronic illnesses. Health Aff 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-526–43. 10.1377/hlthaff.W5.526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, et al. . Use of Medicare claims data to monitor provider-specific performance among patients with severe chronic illness. Health Aff 2004;:Var5–18. 10.1377/hlthaff.var.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, et al. . Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. BMJ 2004;328:607 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, et al. . A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 2004;26:655–72. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess 1978;42:290–4. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton symptom assessment scale. Cancer 2000;88:2164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. . The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. . Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009;18:873–80. 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faschingbauer T, Zisook S, DeVaul R. The Texas Revised Inventory of Grief : Zisook S, edn Biopsychosocial aspects of bereavement. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1987:111–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holland R, Rechel B, Stepien K, et al. . Patients' self-assessed functional status in heart failure by New York Heart Association class: a prognostic predictor of hospitalizations, quality of life and death. J Card Fail 2010;16:150–6. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Committee NYHAC. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart and great vessels. 8th edn Boston: Little, Brown, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol 1984;2:187–93. 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:79 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025692supp001.pdf (756.5KB, pdf)