Abstract

Objective

To assess gender disparity in outcomes among hospitalised patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) or pneumonia.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A tertiary referral centre in Midwest, USA.

Participants

We evaluated 12 265 adult patients hospitalised with ADHF, 15 777 with AMI and 12 929 with pneumonia, from 1 January 1995 through 31 August 2015. Patients were selected using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Prevalence of comorbidities, 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission. Comorbidities were chosen from the 20 chronic conditions, specified by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Logistic regression analysis was conducted adjusting for multiple confounders.

Results

Prevalence of comorbidities was significantly different between men and women in all three conditions. After adjusting for age, length of stay, multicomorbidities and residence, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality between men and women in AMI or ADHF, but men with pneumonia had slightly higher 30-day mortality with an OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.34). There was no significant difference in 30-day readmission between men and women with AMI or pneumonia, but women with ADHF were slightly more likely to be readmitted within 30 days with OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.99).

Conclusion

Gender differences in the distribution of comorbidities exist in patients hospitalised with AMI, ADHF and pneumonia. However, there is minimal clinically meaningful impact of these differences on outcomes. Efforts to address gender difference may need to be diverted towards targeting overall population health, reducing race/ethnicity disparity and improving access to care.

Keywords: internal medicine, cardiology, respiratory infections

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size, multivariable adjustment and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of findings.

A limitation of this study is including all patients that were hospitalised in a single regional tertiary centre; these patients were from several different states and some were from other countries. We might have underestimated the mortality or readmission rates if these patients were readmitted to a different hospital closer to their residency place after discharge.

A limitation of this study is that the majority of the included patients were white; the results may not be generalisable to people from other races.

Introduction

Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and pneumonia are among the most common causes of hospitalisation in the USA, with more than 2.5 million hospitalisations per year, and estimated annual hospital cost of $31.3 billion.1 2 Hospitalised patients with ADHF, AMI or pneumonia are at high risk of death and readmission at 30 days after index hospitalisation.1 2 In the USA, 15.1% of patients with AMI, 11.4% of patients with ADHF and 11.3% of patients with pneumonia die within 30 days after hospitalisation for respective disorders.3 4 Likewise, 21.4%, 16% and 16.5% of patients hospitalised for ADHF, AMI and pneumonia, respectively, are readmitted within 30 days of the first hospitalisation.5 Annually, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services publically reports a comprehensive overview of national performance as part of the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program, using these three conditions.1 2 Risk standardised 30-day mortality and readmission rates are quality performance measures for AMI, ADHF and pneumonia.6 However, these outcomes vary between men and women.7

In the past several decades, gender disparities in clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients with different diseases have been investigated.8 9 Several studies suggested gender differences in clinical outcomes for patients with AMI, ADHF and pneumonia.10–13

Women have worse outcomes for pneumonia than men, with adjusted risk ratio of 1.15 for 28-day mortality.14 Women with acute coronary syndromes were at a higher risk for unadjusted in-hospital death (5.6% vs 4.3%)9 and they are more likely to have adverse outcomes (myocardial infarction, stroke and readmission) compared with men (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.34).15

Although no gender differences were found in outcomes in patients with ADHF, there were significant gender differences in the clinical characteristics at presentation including age and comorbidities.10

Multimorbidity, defined as existence of two or more disorders in an individual patient, has become a public health issue of increasing magnitude. Around one-third of all Americans have multimorbidity (31.5%), and the rate is expected to increase with time.16 Multimorbidity is associated with premature death, propensity for overinvestigation, duplicate tests, medication non-adherence, polypharmacy with increased risk for drug adverse events and a decline in functional status.16 Mutlimorbidity itself may have gender disparities. The US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey when looking at persons 65 years and older found that 83% of women compared with 65% men with coronary artery disease (CAD) had one of the four comorbid conditions (arthritis, chronic lower respiratory tract disease, diabetes mellitus and stroke).17 European data suggest a similar difference in the prevalence of multimorbidity between men and women.18

Although the above data provide sex-related differences in the prevalence of multimorbidity in specific patient population, the disparity in rates of occurrence of comorbid conditions and their impact on early clinical outcome have not been reported by gender for broader hospitalised patients with ADHF, AMI and pneumonia.

To address this gap in knowledge, we evaluated gender-specific differences in the prevalence of individual and multiple comorbid conditions in a large hospital-based patient population with ADHF, AMI and pneumonia. Furthermore, we determined whether the presence of individual or multimorbidity impacts 30-day mortality or readmission by gender independent of demographic and social characteristics.

Methods

Study design and population sample

This is a retrospective study of patients aged ≥18 years hospitalised for ADHF, AMI and pneumonia at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, from 1 January 1995 to 31 August 2015.

We included first hospitalisation in the analysis when a patient had multiple repeat hospitalisations for the same condition, since patients with multiple hospitalisations with the same condition may have higher risk of readmission or mortality within 30 days. The data were extracted by dedicated abstraction personnel using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes (online supplementary tables 1–3). We abstracted data related to age, gender, race, zip code, insurance, principal discharge diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, length of hospital stay, death and readmission by date. The diagnoses of AMI, ADHF and pneumonia were based on physician provider as documented in clinical notes. Patients who refused participation in clinical research were excluded.

bmjopen-2018-022782supp001.pdf (256.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved.

Measure of multicomorbidities

Comorbidities were chosen from 20 chronic conditions (online supplementary tables 4) specified by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health19 using ICD-9-CM codes (online supplementary tables 5). Multicomorbidities were categorised into four groups based on the number of existing chronic conditions: less than two comorbidities, two comorbidities, three comorbidities and four or more comorbidities.

We did not use composite morbidity index such as Charlson, since it needed to be modified for this study. For example, we did not count CAD as one of the comorbidities for patients hospitalised for AMI, the same for congestive heart failure for patients with ADHF.

We excluded four comorbid conditions (autism, schizophrenia, hepatitis and HIV) from the analysis because of very low frequency of occurrence (<1%).

Measures of outcomes

The primary outcomes were prevalence of comorbidities in men and women, 30-day mortality, defined as 30 days from the day of admission with one of the primary diagnosis, and 30-day readmission for any cause since discharge date.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristic data were summarised as mean and SD for continuous variables and as for categorical variables. Prevalence of comorbidities and the number of multimorbidities in men and women were compared using χ2 tests.

Gender differences in 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission were presented as OR. Logistic regression models were developed to estimate the risk of outcomes of interest while controlling for various confounders (age, length of stay, Olmsted county residency and number of comorbidities). Results are reported as ORs and 95% CIs. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant and all analyses were performed using STATA V.14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

A total of 40 971 patients were included during the study period: 12 265 with ADHF, 15 777 with AMI and 12 929 with pneumonia. There were more men in all three conditions, and men were younger (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| AMI=15 777 | ADHF = 12 265 | Pneumonia=12 929 | |||||||

| Men 65% | Women 35% | P value | Men 57 % | Women 43% | P value | Men 55% | Women 45% | P value | |

| Age (SD) | 66.5 (13.3) | 73 (13.3) | <0.001 | 72.3 (13) | 75.4 (13.9) | <0.001 | 69.2 (16.8) | 70.8 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Race % | |||||||||

| Non-white | 12.74% | 14.12% | 0.015 | 14.25 % | 14.25% | 0.997 | 15.65% | 14.70% | 0.14 |

| White | 87.26% | 85.88% | 85.75 % | 85.75% | 84.35% | 85.30% | |||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Arthritis | 3.37% | 5.57% | 0.06 | 4.35% | 6.95% | <0.001 | 4.28% | 7.26% | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 2.42% | 3.89% | <0.001 | 2.81% | 5.25% | <0.001 | 5.09% | 10.31% | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 1.73% | 3.29% | <0.001 | 2.65% | 4.17% | <0.001 | 6.9% | 8.52% | 0.001 |

| Depression | 4.4% | 6.8% | <0.001 | 6.28% | 9.12% | <0.001 | 8.64% | 12.93% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 57.64% | 65.69% | <0.001 | 56.52% | 62.11% | <0.001 | 43.91% | 48.80% | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.4% | 4.73% | <0.001 | 0.97% | 7.16% | <0.001 | 2.09% | 9.00% | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 8.14% | 6.95% | 0.01 | 13.42% | 11.91% | 0.01 | 25.93% | 17.81% | <0.001 |

| Drug abuse | 4.15% | 1.47% | <0.001 | 3.65% | 0.97% | <0.001 | 4.54% | 2.36% | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 44.46% | 40.40% | <0.001 | 1.06% | 27.73% | <0.001 | 20.54% | 17.71% | <0.001 |

| CAD | 56.98% | 41.27% | <0.001 | 27.29% | 17.78% | <0.001 | |||

| CHF | 21.15% | 29.03% | <0.001 | 20.44% | 21.36% | 0.20 | |||

| CKD | 9.49% | 9.24% | 0.60 | 27.93% | 21.62% | <0.001 | 15.28% | 10.71% | <0.001 |

| COPD | 11.02% | 10.84% | 0.73 | 23.50% | 16.67% | <0.001 | 28.19% | 22.8% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 26.18% | 29.62% | <0.001 | 33.75% | 32.31% | 0.09 | 22.78% | 19.31% | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 25.62% | 27.03% | 0.06 | 60.93% | 54.23% | <0.001 | 28.36% | 24.80% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 3.35% | 4.49% | <0.001 | 2.84% | 2.42% | 0.15 | 2.52% | 1.67% | 0.001 |

| Length of stay | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.42 (5.83) | 5.67 (5.76) | 0.01 | 6.02 (10.22) | 5.71 (8.33) | 0.07 | 5.36 (6.01) | 5.13 (6.41) | 0.04 |

ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The prevalence of each comorbidity in men and women was reported in table 1. The majority of deaths due to AMI occurred in the first 10 days, whereas this trend was not evidence for pneumonia or ADHF (online supplementary figure 1–3). The majority of readmissions for all three conditions occurred in the first 15 days (online supplementary figure 4–6).

Summary of outcomes

ADHF

A total of 12 265 patients were hospitalised with ADHF within the study period: 7010 men and 5255 women. Women were older with a mean age of 75.4 years compared with 72.3 years in men. 85.75% of both men and women were Caucasian. 71.94% of men had multicomorbidities compared with 69.99% of women.

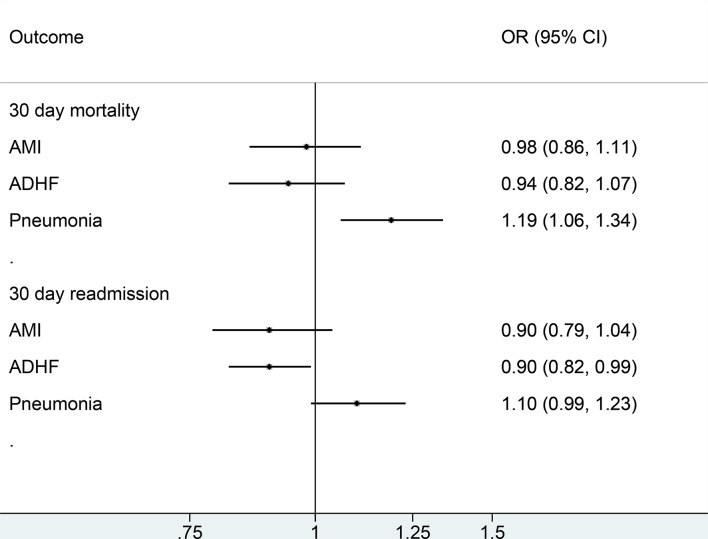

After adjusting for age, length of stay, residence place (Olmsted county vs non-Olmsted) and multicomorbidities, OR for 30-day mortality for men versus women was 0.94 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.07), and OR for 30-day readmission was 0.90 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.99) (table 2 and figure 1).

Table 2.

Adjusted outcomes

| Men versus women | AMI | ADHF | Pneumonia | |||

| Effect size (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| 30-day mortality | OR 0.98 (0.86 to to 1.11) | 0.71 | OR 0.94 (0.82 to 1.07) | 0.39 | OR 1.19 (1.06 to 1.34) | 0.004 |

| 30-day readmission | OR 0.90 (0.79 to 1.04) | 0.16 | OR 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.03 | OR 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 0.08 |

ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

Figure 1.

Adjusted outcomes 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission in men versus women. ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

A subgroup analysis including patients who had CAD was conducted, OR for 30-day mortality was 0.89 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.09), and OR for 30-day readmission was 0.90 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.082).

AMI

Of the 15 777 patients hospitalised with AMI, 10 280 were men and 5497 were women. Women were older, with a mean age of 73 years compared with 66.5 years in men. 86.78% of patients were Caucasian (87% of men and 86% in women) (table 1). 46.73% of men had multicomorbidities compared with 52.17% of women.

After adjusting for age, length of stay, residence place (Olmsted county vs non-Olmsted) and multicomorbidities, OR for 30-day mortality for men versus women was 0.98 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.11), and OR for 30-day readmission was 0.90 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.04) (table 2 and figure 1).

A subgroup analysis including patients who had heart failure was conducted, OR for 30-day mortality was 1.18 (95% CI 1.007 to 1.37) and OR for 30-day readmission was 0.89 (95% CI 0.72 to 1.09).

Pneumonia

Of the 12 929 patients hospitalised with pneumonia within the study period, three were 7073 men and 5856 women. Women were older with a mean age of 70.8 compared with 69.2 years in men. 85% of both men and women were Caucasian. 58.89% of men had multicomorbidities compared with 55.79% of women.

After adjusting for age, length of stay, residence place (Olmsted county vs non-Olmsted) and multicomorbidities, OR for 30-day mortality for men versus women was 1.19 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.34), and OR for 30-day readmission was 1.10 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.23). (table 2) (figure 1)

A subgroup analysis including patients who had CAD was conducted, OR for 30-day mortality was 1.21 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.56) and OR for 30-day readmission was 1.06 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.39).

A subgroup analysis including patients who had heart failure was conducted, OR for 30-day mortality was 1.089 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.33) and OR for 30-day readmission was 1.21 (95% CI 1.007 to 1.46).

Sensitivity analysis

To determine the contemporary status of gender disparities and comorbidities, we conducted a sensitivity analysis focusing on patients who were admitted in the last 5 years. The results were overall consistent with the main analysis, except for 30-day mortality for pneumonia (which became non-significant between men and women whereas mortality was marginally higher in men, in the original analysis) (online supplementary table 6).

We conducted another sensitivity analysis, looking for 15-day mortality and readmission. There were no statistically significant differences in 15-day readmission between men and women in all three conditions. 15-day mortality was marginally higher for pneumonia in men for OR 1.15 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.33) but not statistically significant different in AMI or ADHF (online supplementary table 7).

Discussion

This study suggests that comorbidities are distributed differently between men and women hospitalised for ADHF, AMI and pneumonia. Despite a fairly large sample size, this study showed that gender differences appear to have minimal meaningful impact on outcomes.

In AMI, women are known to less commonly report chest pain or discomfort compared with men; this may lead to gender differences in outcomes of AMI.20 However, in our study, the gender difference in 30-day mortality could be explained by the age difference: women were 6.5 years older on average. After adjusting for residency location and number of comorbidities, age had a significant impact on 30-day mortality, but not gender or multicomorbidities. On the other hand, the only factor that had a significant association with 30-day readmission was multicomorbidities.

In ADHF, men had significantly lower 30-day readmission rate compared with women, while they did not have a significant difference in 30-day mortality. A sensitivity analysis including only patients for the last 5 years showed similar results. Multicomorbidity did not have a significant effect on 30-day mortality or readmission. This might be explained by difference in symptoms presentations or difference in access to medical care between men and women. For example, men used to have higher invasive cardiac procedures than women in a previously published study.21

Men with pneumonia had significantly higher 30-day mortality compared with women, but no significant difference in 30-day readmission. Multicomorbidities had a significant effect on 30-day readmission in men but not in women.

Comparison with existing literature

Our findings in AMI were consistent with previously published studies12 22 that showed a higher 30-day mortality rate in women verses men, but no significant difference after adjustment for other variables. In these studies, they include elderly patients only (>65 years old) while we had no age restriction, but yet, in all of these studies, women were older, and had differences in comorbidities compared with men. In ADHF, our results were consistent with a previously published study that used Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry between 2001 and 200410; in both studies, there was no significant difference in in-hospital mortality between men and women.

In pneumonia, our study showed that men have worse outcomes than women, unlike a previous study14 that found that women have worse outcomes for community-acquired pneumonia with 28-day mortality OR of 1.15 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.30). However, our study included all types of pneumonia, and it was consistent with another study that used the Medicare database and showed worse outcomes in men.23

Limitations and strengths

A limitation of this study is that we used ICD-9 codes for identifying patients. It was not feasible to review charts for such a large number of patients; therefore, we had to depend on administrative and billing codes. New research using the recent ICD-10 coding is needed to study the consistency of prevalence and implication of comorbidities on early outcomes in hospitalised patients. Another limitation is that we included all patients that were hospitalised in a single regional tertiary centre; these patients were from several different states and some were from other countries. We might have underestimated the mortality or readmission rates if these patients were readmitted to a different hospital closer to their residency place after discharge. Making this less concerning is the fact that we found gender to be an independent variable from residency place; in addition, we adjusted for residency place (Olmsted county where the hospital is vs non-Olmsted county). Another limitation is that the majority of our included patients were white; our results may not be generalisable to people from other races. Other limitation in our data is that we have included only the first hospitalisation; some patients have likely had multiple repeat hospitalisations for the same condition. The strengths of this study include the large sample size, multivariable adjustment and sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of findings.

Clinical and policy implication

Although this study showed that women hospitalised for ADHF had higher 30-day readmission rate, the absolute risk was small with a number needed to harm 88 patients (95% CI 48 to 445). For pneumonia, women had lower mortality, with a number needed to harm 61 patients (95% CI 36 to 202). With this minimal clinically meaningful impact of these differences on the early outcomes of these three important conditions, efforts to address gender difference may need to be diverted towards targeting overall population health, where outcomes of these conditions are still suboptimal in both genders, or towards reducing race/ethnicity disparity, or improving access to care differences.

Conclusion

Gender disparities interact with comorbidities and impact mortality and readmission. However, this effect varies according to the conditions, seems to be unpredictable and has a minimal meaningful impact on outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: MA: conception and design of the study, data collection, data analysis, interpreted results, drafted and revised manuscript; ZW: data analysis, manuscript revision and approval of final draft; MHM: contributed to study design, manuscript development and approval of final draft; MY: developed the idea for the study, interpreted results, revised manuscript and approval of final draft.

Funding: This publication was made possible by CTSA grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Disclaimer: Contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Committee (IRB).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Jennifer Schwartz P, Kelly M MPH, Strait M, et al. CMS Medicare Hospital Quality Chartbook, Performance Report on Outcome Measures, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. Costs for hospital stays in the united states, 2010: statistical brief #146. [PubMed]

- 3. Suter LG, Li SX, Grady JN, et al. National patterns of risk-standardized mortality and readmission after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: update on publicly reported outcomes measures based on the 2013 release. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1333–40. 10.1007/s11606-014-2862-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindenauer PK, Bernheim SM, Grady JN, et al. The performance of US hospitals as reflected in risk-standardized 30-day mortality and readmission rates for medicare beneficiaries with pneumonia. J Hosp Med 2010;5:E12–E18. 10.1002/jhm.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khera R, Dharmarajan K, Wang Y, et al. Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program with mortality during and after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e182777 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Outcome Measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/OutcomeMeasures.html.

- 7. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355–63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crabtree TD, Pelletier SJ, Gleason TG, et al. Gender-dependent differences in outcome after the treatment of infection in hospitalized patients. JAMA 1999;282:2143–8. 10.1001/jama.282.22.2143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blomkalns AL, Chen AY, Hochman JS, et al. Gender disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of non-st-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: large-scale observations from the crusade (can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the american college of cardiology/american heart association guidelines) national quality improvement initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:832–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galvao M, Kalman J, DeMarco T, et al. Gender differences in in-hospital management and outcomes in patients with decompensated heart failure: analysis from the acute decompensated heart failure national registry (ADHERE). J Card Fail 2006;12:100–7. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomsen RW, Riis A, Nørgaard M, et al. Rising incidence and persistently high mortality of hospitalized pneumonia: a 10-year population-based study in Denmark. J Intern Med 2006;259:410–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2009;302:874–82. 10.1001/jama.2009.1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, et al. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1999;341:217–25. 10.1056/NEJM199907223410401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arnold FW, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Outcomes in females hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia are worse than in males. Eur Respir J 2013;41:1135–40. 10.1183/09031936.00046212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, et al. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart 2009;95:20–6. 10.1136/hrt.2007.138537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyd CM, Fortin M. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 2010;32:451–74. 10.1007/BF03391611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weiss CO, Boyd CM, Yu Q, et al. Patterns of prevalent major chronic disease among older adults in the United States. JAMA 2007;298:1158–62. 10.1001/jama.298.10.1160-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abad-Díez JM, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Poncel-Falcó A, et al. Age and gender differences in the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in the older population. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:75 10.1186/1471-2318-14-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, et al. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E66 10.5888/pcd10.120239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, et al. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2405–13. 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giles WH, Anda RF, Casper ML, et al. Race and sex differences in rates of invasive cardiac procedures in US hospitals. Data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:318–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, et al. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA 2012;307:813–22. 10.1001/jama.2012.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaplan V, Angus DC, Griffin MF, et al. Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:766–72. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2103038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022782supp001.pdf (256.8KB, pdf)