Abstract

Objective

To characterise a population-based cohort of patients with Gaucher disease (GD) in Israel relative to the general population and describe sociodemographic and clinical differences by disease severity (ie, enzyme replacement therapy [ERT] use).

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted.

Setting

Data from the Clalit Health Services electronic health record (EHR) database were used.

Participants

The study population included all patients in the Clalit EHR database identified as having GD as of 30 June 2014.

Results

A total of 500 patients with GD were identified and assessed. The majority were ≥18 years of age (90.6%), female (54.0%), Jewish (93.6%) and 34.8% had high socioeconomic status, compared with 19.0% in the general Clalit population. Over half of patients with GD with available data (51.0%) were overweight/obese and 63.5% had a Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥1, compared with 46.6% and 30.4%, respectively, in the general Clalit population. The majority of patients with GD had a history of anaemia (69.6%) or thrombocytopaenia (62.0%), 40.4% had a history of bone events and 22.2% had a history of cancer. Overall, 41.2% had received ERT.

Conclusions

Establishing a population-based cohort of patients with GD is essential to understanding disease progression and management. In this study, we highlight the need for physicians to monitor patients with GD regardless of their ERT status.

Keywords: gaucher disease, enzyme replacement therapy, ert, electronic health records

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The electronic health record (EHR) data enabled the examination of a large, population-based cohort of patients with Gaucher disease (GD).

The availability of data from various sources in the Clalit EHR database, including medical, pharmacy and laboratory records, was instrumental in identifying and characterising this cohort.

Identification of patients with GD using diagnostic tests such as bone marrow biopsy and genetic testing was not available in the Clalit database owing to the privacy limitations of the EHR data; however, patients with GD were likely identified using other sources.

Imaging and clinical notes were not available in the EHR, thus limiting the ability to evaluate treatment needs and track disease management.

Introduction

Gaucher disease (GD) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a mutation in the beta-glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene.1 2 GD has variable phenotypic expression and is categorised based on the absence (type 1) or presence (types 2 and 3) of neurological manifestations.3 4 Type 1 is often diagnosed in adulthood and is the most common, with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 30 000 to 1 in 40 000 of the total population.5 Types 2 and 3 are less frequent than type 1, with type 2 often fatal in infancy, and occur in fewer than 1 in 100 000 of the population.5

The incidence of GD in Ashkenazi Jews, the majority of whom reside in Israel, is linked with a high carrier frequency of the mutation N370S of 1 in 17.5 and a disease prevalence of 1 in 850.3 6–11 Although disease severity for this mutation occurs on a spectrum, up to 90% of N370S homozygotes have mild disease or are asymptomatic.7 8 Thus, while patients can be tested for genetic mutation and GBA activity, many experience delays or misdiagnosis before receiving the appropriate diagnosis and management.3 12

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and substrate reduction therapy are treatment options developed in the past two decades with the ability to reverse some of the clinical features associated with GD.13 Despite these advances, physicians face challenges treating and managing patients with GD due to clinical heterogeneity and variable progression rates of the disease.14

Most GD studies collect data from patients receiving pharmaceutical treatment, with registry-based studies being one of the major resources for descriptive and management data on the GD population.1 6 9 10 15–17 As a result, there is a lack of observational data on non-symptomatic and untreated patients regarding long-term follow-up and health outcomes. Population-based electronic health records (EHRs) can provide detailed sociodemographic and clinical data to characterise real-world populations of patients with GD. The availability of data from various sources within EHR, such as registry data, electronic medical records and claims, may assist in identifying a greater proportion of patients who do not require treatment (ie, mild cases).

Population-based EHR studies of GD are difficult to implement for several reasons. First, International Classification of Diseases ninth revision (ICD-9) codes are not specific for GD. Second, since GD is rare, data from large populations are needed to assess healthcare management and outcomes. Finally, since GD varies symptomatically from mild to severe, many cases may not require treatment or will not even be diagnosed.12

The goal of this study was to characterise a population-based cohort of patients with GD relative to the general population and describe sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by disease severity, as indicated by ERT use.

Methods

Data source

Data were collected from the Clalit Health Services (CHS) health maintenance organization in Israel (herein ‘Clalit’). CHS is the largest of Israel’s four providers of universal healthcare and is characterised by an extremely low annual turnover of <1%.18 CHS has approximately 4 217 000 members, representing >50% and >60% of the Israeli population over the ages of 21 and 65 years, respectively.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using the CHS EHR database. The data include demographic data, clinical diagnoses, laboratory data results, medical treatment, and medications collected and maintained in a central data warehouse since 1998.

Study population

The study population included all patients in the Clalit EHR database identified as having GD as of 30 June 2014, based on at least one of the following criteria (figure 1): (1) a listing in Gaucher Registry19; (2) a diagnosis in the CHS Chronic Disease Registry (CDR)20; (3) a permanent diagnosis in medical records of ICD-9=272.7 with free text of ‘Gaucher’; (4) the purchase of ≥1 ERT medications (imiglucerase, velaglucerase alfa, taliglucerase alfa) or (5) a glucosidase enzymatic test result of ≤3 nmol/hour/mg.21 Owing to the limited availability of hospital laboratory data in the Clalit EHR, enzymatic test data identified only 7.4% of the study population. The overlap of these criteria was further reviewed internally to minimise misclassification. The earliest date of any one of these criteria was considered the index date.

Figure 1.

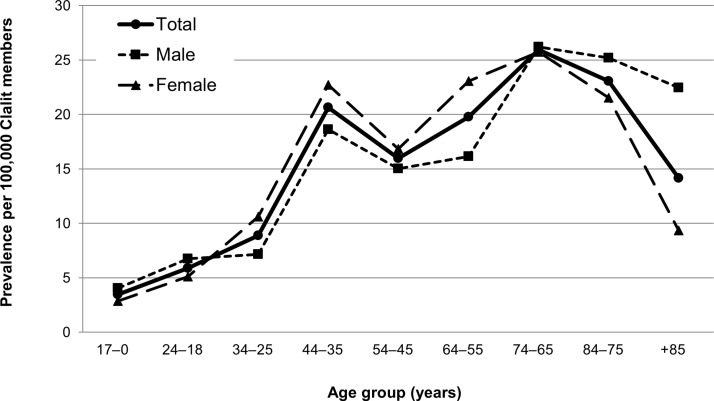

Prevalence of Gaucher disease in the Clalit population by age group and sex, 2014.

Excluded were patients with GD with non-continuous membership in Clalit; with an index date after 30 June 2014; who died during the study and had <6 months membership prior to the index date; and patients who were born within 6 months of the index date and had <6 months membership after the index date. Patients with a text-based diagnosis that included family history, suspected disease status or genetic carrier were also excluded.

The Clalit general population was used as the comparison group and included all Clalit members with continuous membership for 6 months prior to and after 1 January 2014.

Measures

Demographic data were collected at the index date for age, sex and socioeconomic status (SES) (low, medium, high or missing). Individual-level SES data are not collected by any health plan in Israel owing to Israeli law; therefore, SES scores derived by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics and based on small statistical areas were used.22

Clinical characteristics included body mass index (BMI) (continuous and categorical as: underweight [<18.5 kg/m2]), normal weight [18.5 to <25 kg/m2], overweight [25 to <30 kg/m2], obese [≥30 kg/m2]) and smoking habits (current smoker, former smoker or never smoker). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)23 was used to represent a weighted sum of multiple comorbid conditions predictive of mortality, with higher scores indicating a greater comorbid burden on the patient.

Complications and comorbidities, which are prevalent among patients with GD,1 were identified using ICD-9 coding, CHS, CDR and Clalit Research Institute algorithms.20 Disease complications included anaemia (ICD-9: 280.x to 285.9 or any abnormal haemoglobin (Hb) test result during the study period: Hbmales>15 years<13.0 g/dL; Hbfemales>15 years and children 12–15 years<12.0 g/dL; Hbchildren 5–11 years<11.5 g/dL or Hbchildren 0–5 years<11.0 g/dL), thrombocytopaenia (ICD-9: 287.5 or any blood platelet count <150×109/L), hepatomegaly (ICD-9: 789.1), splenomegaly (ICD-9: 789.2), bone complications (osteoarthritis (ICD-9: 715), muscle pain (ICD-9: 729.1/2) and bone disorders (ICD-9: 733.0/1/3/4/9)), calcification of cardiac valves (ICD-9: 424.0) and pulmonary hypertension (ICD-9: 416). Disease comorbidities included patients with a diagnosis of malignant neoplasms (ICD-9: 140–208; including multiple myeloma (ICD-9: 203.0)), diabetes (ICD-9: 250), gallstones (ICD-9: 574), Parkinson’s disease (ICD-9: 332) or peripheral neuropathy (ICD-9: 356.8/9).

ERT use during the study period, which can serve as a proxy for patients with more severe disease, was defined as any documented purchase of imiglucerase, velaglucerase alfa or taliglucerase alfa at any time and dichotomized into users (ERT+) and non-users (ERT–). Substrate reduction therapy is not used in Israel to treat GD.

Analysis

Age-specific prevalence was calculated using the entire Clalit population. Age-standardised rates (95% CIs) of GD were calculated using direct standardisation according to the Israeli population in 201424 as the weighted average of each age group-specific rate adjusted to the proportion of persons in that age group of the reference (Israeli) population. Descriptive analyses were used to characterise the study populations. Bivariate comparisons between groups were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables. Adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing was noted as the reduction in p value threshold from 0.05 by the number of tests conducted. All analyses were conducted using SPSS V.22.0 (IBM) and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology cohort reporting guidelines were used.25

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in the design, conduct or interpretation of the study. Due to anonymity, results cannot be disseminated to study participants.

Results

A total of 500 patients with GD were identified in the Clalit database as of 30 June 2014 using the criteria described. The age-standardised prevalence of GD was 11.6 (95% CI 11.0 to 12.1) per 100 000. Age-specific rates ranged from 5.3 per 100 000 for members ≤34 years of age to 20.2 per 1 00 000 for members ≥35 years of age (figure 1). There was no statistical difference in prevalence between the adult age groups (p>0.05), likely due to the low rates recorded.

In comparison with the general Clalit membership, most patients with GD were ≥18 years of age (GD population: 90.6% vs Clalit: 68.3%, p<0.001), female (GD population: 54.0% vs Clalit: 51.1%, p=0.199), of Jewish ethnicity (GD population: 93.6% vs Clalit: 73.4%, p<0.001) and belonged to a high SES group (GD population: 34.8% vs Clalit: 19.0%, p<0.001) (table 1). The prevalence of overweight/obesity among those with available data was 51.0% for patients with GD and 46.5% for the general Clalit population (p=0.049). Among those with CCI estimates, 64% of patients with GD had a CCI ≥1, compared with 30.4% in the general Clalit population (p<0.001). Among those with smoking documentation, the rate of former or current smokers among the patients with GD was 27.7%, compared with 33.7% among the general Clalit population (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the Gaucher disease population with the Clalit population

| Clalit, n (%) n=4 196 955 |

Gaucher disease, n (%) n=500 |

|

| Age group, years | ||

| 0–17 | 1 329 892 (31.7) | 47 (9.4) |

| 18–24 | 350 485 (8.4) | 22 (4.4) |

| 25–34 | 639 653 (15.2) | 57 (11.4) |

| 35–44 | 516 669 (12.3) | 103 (20.6) |

| 45–54 | 386 840 (9.2) | 62 (12.4) |

| 55–64 | 410 716 (9.8) | 80 (16.0) |

| 65–74 | 290 703 (6.9) | 73 (14.6) |

| 75–84 | 188 913 (4.5) | 44 (8.8) |

| 85+ | 83 084 (2.0) | 12 (2.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 2 051 087 (48.9) | 230 (46.0) |

| Female | 2 145 868 (51.1) | 270 (54.0) |

| Ethnicity* | ||

| Jewish | 3 081 398 (73.4) | 468 (93.6) |

| Non-Jewish | 1 115 553 (26.6) | 32 (6.4) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Low | 1 889 113 (45.0) | 93 (18.6) |

| Medium | 1 498 839 (35.7) | 211 (42.2) |

| High | 798 894 (19.0) | 174 (34.8) |

| Missing | 10 109 (0.2) | 22 (4.4) |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight | 168 091 (4.0) | 16 (3.2) |

| Normal | 1 835 273 (43.7) | 220 (44.0) |

| Overweight | 1 048 702 (25.0) | 178 (35.6) |

| Obese | 697 333 (16.6) | 68 (13.6) |

| Missing | 447 556 (10.7) | 18 (3.6) |

| Smoking habits (adults) | ||

| Never smoker | 1 878 360 (65.5) | 323 (71.3) |

| Former smoker | 403 207 (14.1) | 64 (14.1) |

| Current | 549 941 (19.2) | 60 (13.2) |

| Missing | 35 555 (1.2) | 6 (1.3) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||

| <1 | 2 863 680 (68.2) | 175 (35.0) |

| 1 to <2 | 693 451 (16.5) | 128 (25.6) |

| ≥2 | 554 988 (13.2) | 177 (35.4) |

| Missing | 84 836 (2.0) | 20 (4.0) |

*Data were missing for four adults from the Clalit population.

Of the 500 patients with GD, 41.2% (n=206) had received ERT with no differences in sociodemographic characteristics between ERT+ and ERT– groups (p>0.05) (table 2). Clinical characteristics such as BMI and smoking were also similar between ERT+ and ERT– groups, apart from CCI. The proportion of patients with CCI ≥1 was higher for ERT+ compared with to ERT− patients (79.4% vs 52.3%, respectively, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for the Gaucher disease population by ERT use, 2014

| ERT+, n (%) n=206 |

ERT–, n (%) n=294 |

P values* | |

| Age group, years | 0.242 | ||

| 0–17 | 15 (7.3) | 32 (10.9) | |

| 18–24 | 8 (3.9) | 14 (4.8) | |

| 25–34 | 31 (15.0) | 26 (8.8) | |

| 35–44 | 48 (23.3) | 55 (18.7) | |

| 45–54 | 26 (12.6) | 36 (12.2) | |

| 55–64 | 31 (15.0) | 49 (16.7) | |

| 65–74 | 35 (17.0) | 38 (12.9) | |

| 75–84 | 9 (4.4) | 35 (11.9) | |

| 85+ | 3 (1.5) | 9 (3.1) | |

| Sex | 0.440 | ||

| Male | 99 (48.1) | 131 (44.6) | |

| Female | 107 (51.9) | 163 (55.4) | |

| Ethnicity† | |||

| Jewish | 196 (95.1) | 272 (92.5) | |

| Non-Jewish | 10 (4.9) | 22 (7.5) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.852 | ||

| Low | 41 (19.9) | 52 (17.7) | |

| Medium | 83 (40.3) | 128 (43.5) | |

| High | 72 (35.0) | 102 (34.7) | |

| Missing | 10 (4.9) | 12 (4.1) | |

| Body mass index | 0.189 | ||

| Underweight | 9 (4.4) | 7 (2.4) | |

| Normal | 87 (42.2) | 133 (45.2) | |

| Overweight | 82 (39.8) | 96 (32.7) | |

| Obese | 22 (10.7) | 46 (15.6) | |

| Missing | 6 (2.9) | 12 (4.1) | |

| Smoking habits (adults) | 0.199 | ||

| Never smoker | 146 (76.4) | 177 (67.6) | |

| Former smoker | 24 (12.6) | 40 (15.3) | |

| Current | 19 (9.9) | 41 (15.6) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | <0.001 | ||

| <1 | 41 (19.9) | 134 (45.6) | |

| 1 to <2 | 77 (37.4) | 51 (17.3) | |

| ≥2 | 81 (39.3) | 96 (32.7) | |

| Missing | 7 (3.4) | 13 (4.4) | |

ERT+, users of ERT; ERT–, non-users of ERT.

*χ2, Fisher’s or trend tests were used to assess differences in distribution between ERT+ and ERT− groups.

†Data were missing for four adults from the Clalit population.

ERT. enzyme replacement therapy.

Distribution of disease complications and comorbidities for the GD population and per ERT use showed that most patients with GD had anaemia (69.6%) or thrombocytopaenia (62.0%), 40.4% had a history of bone events and 22.2% had a history of malignancy (table 3). Patients receiving ERT had higher rates of complications compared with those not receiving ERT; however, statistically significant differences, after adjustment for multiple comparisons, were observed only for anaemia (ERT+: 76.7% vs ERT–: 64.6%, p=0.004), hepatomegaly (ERT+: 10.7% vs ERT–: 5.1%, p=0.019) and thrombocytopaenia (73.8% vs 53.7%, respectively, p<0.001). Prevalent comorbidities were similar between ERT use groups.

Table 3.

Distribution of disease complications and comorbid conditions for the Gaucher disease population, overall and by ERT use, 2014

| Total, n (%) n=500 |

ERT+, n (%) n=206 |

ERT–, n (%) n=294 |

P values* | |

| Complications (at any time) | ||||

| Anaemia | 348 (69.6) | 158 (76.7) | 190 (64.6) | 0.004 |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 310 (62.0) | 152 (73.8) | 158 (53.7) | <0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 37 (7.4) | 22 (10.7) | 15 (5.1) | 0.019 |

| Splenomegaly | 78 (15.6) | 35 (17.0) | 43 (14.6) | 0.474 |

| Bone event | 202 (40.4) | 89 (43.2) | 113 (38.4) | 0.285 |

| Calcification of cardiac valves | 19 (3.8) | 8 (3.9) | 11 (3.7) | 0.935 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 20 (4.0) | 12 (5.8) | 8 (2.7) | 0.082 |

| Comorbidities (at any time) | ||||

| Cancer | 111 (22.2) | 42 (20.4) | 69 (23.5) | 0.415 |

| Multiple myeloma | 5 (1.0) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) | † |

| Diabetes | 64 (12.8) | 26 (12.6) | 38 (12.9) | 0.920 |

| Gallstones | 54 (10.8) | 21 (10.2) | 33 (11.2) | 0.715 |

| Parkinsonism | 15 (3.0) | 7 (3.4) | 8 (2.7) | 0.663 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | † |

ERT+, users of ERT; ERT–, non-users of ERT.

*Adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing reduces the p values threshold by the number of tests (n=11; to p=0.005).

†Comparison tests were not calculated for prevalence rates with low numbers and high variance.

ERT, enzyme replacement therapy.

Discussion

This study is the first to use EHR data to provide detailed sociodemographic and clinical data characterising a population-based cohort of patients with GD. We identified 500 patients with GD, consistent with the expected total number of patients in Israel and the coverage size of the Clalit health plan,8 and calculated an age-standardised prevalence of 11.6 cases per 100 000 persons. The slight dip in prevalence observed for the 45–64 years age group may be due to smaller number of Clalit members in that age group. The GD population in Israel differs from the general Clalit population in that it is older, has slightly more females and is primarily Jewish. Within the GD population, approximately two in five patients receive ERT. While there were no substantial differences in sociodemographic characteristics or comorbidities between patients with GD receiving ERT and those not receiving ERT, GD-related complications (which can serve as a trigger to initiating ERT) were more prevalent and CCI was higher in patients receiving ERT.

The prevalence of GD found in this study is 10-fold higher than reported rates worldwide.5 17 Although we cannot directly identify Ashkenazi descent in Israel, owing to data constraints, there are well-documented studies showing that the majority of patients with GD in Israel have type 1 disease and are of Ashkenazi descent.7 8 10 The most frequent N370S mutation among Ashkenazi Jews typically presents as a milder or subclinical form of GD,7 10 which is consistent with the relatively high proportion of adults in our GD cohort. As noted above, the more severe forms of Gaucher, types 2 and 3 are more typical of children and young adults.5 Disease prevalence among Ashkenazi Jews is expected as 1 in 850.11 Assuming a population of 8 million in Israel, of which 80% are of Jewish origin, 50% of those with Jewish origin are of Ashkenazic descent and 50% are members in the CHS, we expect approximately 1900 Clalit patients with GD.3 7 8 10 11 26 Furthermore, most GD cases are concealed by a mild or asymptomatic disease manifestation of the N370S mutation that is present in 90% of cases.7 8 Thus, identification of 500 cases in the CHS likely reflects the 10% of cases who are not mild (ie, receive ERT n=204) and the remaining 90% who have been diagnosed but do not require strict management (ie, do not receive ERT, n=296). By contrast, the 460 patients in the Gaucher Outcome Survey (GOS), the primary treatment centre in Israel, likely reflect non-mild cases. Other differences in demographic characteristics, SES and health behaviours between patients with GD and the general Clalit population are likely a reflection of the variations between the culturally homogeneous cohort (ie, primarily of Ashkenazi origin) and Israel’s diverse population of different descents.26

Among patients with GD, we report an ERT treatment prevalence of 41.2%, similar to that reported in a national examination of the treatment approval policy in Israel, but substantially lower than the reported rate of >70% from the International Collaborative Gaucher Group (ICGG) registry, the French GD registry, the GOS, or from a large cross-sectional survey in Spain.10 13 17 27 This disparity is likely due to differences in cohort design between registry and population-based data as well as distribution of mutation type, as noted above. No differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics were observed between patients receiving ERT, apart from CCI, which is an indicator of treatment need, similar to findings from a hospital-based cross-sectional study of GD treated and untreated patients27

Type 1 GD encompasses phenotypically diverse patients and is associated with a range of complications and comorbidities.13 28 29 Skeletal involvement, resulting in bone resorption, infarction and joint pain, is a major GD-related complication leading to significant morbidity if untreated.30–32 Results of the present study indicate that a bone event occurred in 40.4% of patients with GD, which is lower than the reported rate of 65.0% in other GD populations, such as those from the ICGG registry who had been treated with ERT for 2–5 years.30 This is unsurprising, given that the Clalit cohort is population based, rather than treatment based. In this study, more than 62% of patients with GD had a history of anaemia or thrombocytopaenia, with higher rates for those who received ERT than for those who did not. This was an expected finding, since these haematological abnormalities are primary indicators of disease progression and referral for pharmaceutical treatment.3 Pulmonary hypertension was described in 4.0% of the GD population, with no difference between patients who did and did not receive ERT. In contrast, a previous study showed that among 98 patients with GD, pulmonary hypertension was present in 30.0% of those who did not receive ERT and in 7.4% among those who did.29 We found the rate of calcification of cardiac valves, which is typical of patients with type 3 GD,3 was 3.8%. This latter finding is quite high and may represent the higher prevalence of type 3 GD among non-Jews or other non-GD-related aetiologies. Finally, similar to a recent cross-sectional hospital-based study in Spain,27 rates of GD-related complications were relatively high even among patients who did not receive ERT, suggesting an unmet need in disease management.

Health status and comorbidities associated with GD, including obesity, malignancies, diabetes, gallstones and Parkinson’s disease, were examined in this study.3 16 28 33 34 Data suggest that the role of lysosomes in metabolic pathways, which affect energy balance, glucose and lipid metabolism, cardiovascular risk and liver disease, may result in an increased risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease and hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with lysosomal disorders.34–38 Our findings of higher rates of overweight and obesity among patients with GD compared with the general population, for example, support these lysosome-related mechanisms. We observed high rates of malignancies in the GD population, compared with previously published reports.15 39 Among patients with GD, rates of Parkinson’s disease were similar to those observed from a study of patients with GD in the USA and Israel, and these rates were higher compared with non-carrier controls.40 Over the past two decades, studies have shown that GBA mutations are associated with a 7.6% to 29.7% increased lifetime risk for Parkinson’s disease28 41 and an increased risk of 25.0% for multiple myeloma.39 The observed rates for diabetes and gallstones, although not age or sex adjusted, were similar to published rates for Israel and worldwide.42 43 We found only two patients with reported peripheral neuropathy (0.4%), substantially lower than the observed prevalence rates in type 1 GD of 5%–7%,15 which may be due to improved care over time and study design. It is important to note that no differences were observed between ERT groups for these prevalent comorbidities.

Higher rates of complications and comorbidities associated with GD and among those receiving ERT would suggest an increased healthcare burden associated with this disease. In this GD cohort, higher rates of healthcare resource utilisation (community care visits, specialist visits, ambulatory admissions, hospital admissions and imaging use) were observed compared with the general population and among subgroups with and without bone events or haematological abnormalities and/or organomegaly.44 Further studies should examine the burden associated with ERT use as well as other indicators of effectiveness of therapy and changes in quality of life.45

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is its use of EHR data to examine a large, population-based cohort of patients with GD. The availability of data from various sources in the Clalit EHR database was instrumental in assembling this cohort. As such, we were able to identify a greater proportion of patients who did not require ERT (ie, mild cases) than are specialist-based registries that represent treated patients (ie, severe cases). Cohort and registry studies, in contrast to randomised controlled trials, allow for an extended follow-up period that can inform on long-term treatment patterns, complications and outcomes, which is especially important for rare diseases.

This study has several limitations. First, identification of patients with GD through diagnostic tests such as bone marrow biopsy and genetic testing was not available in the Clalit database owing to the privacy limitations of the EHR data. Second, limited data availability may also have applied to glucosidase enzymatic test data, as we observed a particularly low percentage of patient-tested data. However, patients requiring any physician attention, ranging from a single diagnosis-related encounter to an ERT prescription, were identified, thereby minimising selection bias in the identification of the GD study population. Third, imaging results (eg, ultrasound for spleen or liver volume), which is commonly used among patients with GD to evaluate treatment needs and track management of those receiving ERT, were not available.39 Similarly, clinical notes, which could be used to identify disease severity, treatment history or health history (eg, splenectomies) prior to EHR integration, were not available. Fourth, the relationship between disease complications and ERT findings is unclear and should be considered. Finally, this study reflects patients with GD in Israel and may not represent the wider global GD community in mutation type, severity or treatment patterns.

Conclusions

The present study used EHR data to identify patients with GD and provide a population-based cohort that offers real-world evidence relating to this disease. We confirmed the high prevalence of GD among the Israeli population, with high concomitant rates of malignancy and Parkinson’s disease. Notably, patients with GD receiving ERT tended to have a history with higher rates of anaemia or thrombocytopaenia compared with those not receiving ERT, although differences in sociodemographic or comorbid characteristics between GD ERT groups were not observed. These findings highlight the need for physicians to monitor patients with GD regardless of their ERT status.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Megan J. Shen for assistance with literature review and writing.

Footnotes

Contributors: All of the authors (DHJ, MD, AJ, NF-M, AB, HG, HR, AB and ML-R) contributed to the conception of the study, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Shire.

Competing interests: NF-M, AB, HG, NF-M, AB and ML-R have nothing to declare. DHJ is and MD was employed by Kantar Health, which received fees from Shire for data analysis and reporting of this study. AJ was full-time employee of Shire at the time of the study.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The present study was approved by the Clalit Institutional Review Board, Meir Hospital

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Anonymised data were used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Grabowski GA, Kolodny EH, Weinreb NJ, et al. . Gaucher disease: phenotypic and genetic variation : Scriver C, Beaudet A, Valle D, Slye W. The online metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stirnemann J, Belmatoug N, Camou F, et al. . A Review of Gaucher disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:441 10.3390/ijms18020441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zimran A. How I treat Gaucher disease. Blood 2011;118:1463–71. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-308890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agency EM. Gaucher disease A strategic collaborative approach from EMA and FDA Gaucher disease A Strategic Collaborative Approach from EMA and FDA Table of contents. London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta A. Epidemiology and natural history of Gaucher’s disease. Eur J Intern Med 2006;17:S2–5. 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charrow J, Andersson HC, Kaplan P, et al. . The Gaucher registry. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2835 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horowitz M, Pasmanik-Chor M, Borochowitz Z, et al. . Prevalence of glucocerebrosidase mutations in the Israeli Ashkenazi Jewish population. Hum Mutat 1998;12:240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zuckerman S, Lahad A, Shmueli A, et al. . Carrier screening for Gaucher disease: lessons for low-penetrance, treatable diseases. JAMA 2007;298:1281–90. 10.1001/jama.298.11.1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nalysnyk L, Rotella P, Simeone JC, et al. . Gaucher disease epidemiology and natural history: a comprehensive review of the literature. Hematology 2017;22:65–73. 10.1080/10245332.2016.1240391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deegan P, Fernandez-Sasso D, Giraldo P, et al. . Treatment patterns from 647 patients with Gaucher disease: an analysis from the Gaucher Outcome Survey. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases 2018;68:218–25. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zimran A, Elstein D, et al. . Lipid storage diseases : Lichtman M, Kipps T, Seligsohn U, Kaushansky K, Prchal JT. Hematology2. 8th edition. edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010:1065–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mistry PK, Sadan S, Yang R, et al. . Consequences of diagnostic delays in type 1 Gaucher disease: the need for greater awareness among hematologists-oncologists and an opportunity for early diagnosis and intervention. Am J Hematol 2007;82:697–701. 10.1002/ajh.20908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersson HC, Charrow J, Kaplan P, et al. . Individualization of long-term enzyme replacement therapy for Gaucher disease. Genet Med 2005;7:105–10. 10.1097/01.GIM.0000153660.88672.3C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weinreb NJ, Aggio MC, Andersson HC, et al. . Gaucher disease type 1: revised recommendations on evaluations and monitoring for adult patients. Semin Hematol 2004;41:15–22. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chérin P, Rose C, de Roux-Serratrice C, et al. . The neurological manifestations of Gaucher disease type 1: the French Observatoire on Gaucher disease (FROG). J Inherit Metab Dis 2010;33:331–8. 10.1007/s10545-010-9095-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mistry PK, Taddei T, vom Dahl S, et al. . Gaucher disease and malignancy: a model for cancer pathogenesis in an inborn error of metabolism. Crit Rev Oncog 2013;18:235–46. 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2013006145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stirnemann J, Vigan M, Hamroun D, et al. . The French Gaucher’s disease registry: clinical characteristics, complications and treatment of 562 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:77 10.1186/1750-1172-7-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen R, Rabin H. Membership in health plans 2013. Report of the national health insurance institute [Hebrew]. Jerusalem, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. of HM. National health insurance regulations (cost deduction for critical illnesses). Report number 15/09. Jerusalem, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rennert G, Peterburg Y. Prevalence of selected chronic diseases in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J 2001;3:404–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beutler E, Beta-glucosidase KB, et al. : Williams W, Beutler E, Erslev A, Lichtman M. Hematology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990:1765–1763. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Characterization and classification of geographical units by the socio-economic level of the population, 2008 Census of Population and Housing [Hebrew]. Jerusalem, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Central Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Bulletin. Jerusalem, 20142015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DellaPergola S. Sepharadic and oriental and quot; Jews in Israel and Western countries: Migration, Social Change, and Identification. Jerusalem: Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giraldo P, Pérez-López J, Núñez R, et al. . Patients with type 1 Gaucher disease in Spain: A cross-sectional evaluation of health status. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2016;56:23–30. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brautbar A, Abrahamov A, Hadas-Halpern I, et al. . Gaucher disease in Arab patients at an Israeli referral clinic. Isr Med Assoc J 2008;10:A391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mistry PK, Sirrs S, Chan A, et al. . Pulmonary hypertension in type 1 Gaucher’s disease: genetic and epigenetic determinants of phenotype and response to therapy. Mol Genet Metab 2002;77:91–8. 10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weinreb NJ, Charrow J, Andersson HC, et al. . Effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy in 1028 patients with type 1 Gaucher disease after 2 to 5 years of treatment: a report from the Gaucher Registry. Am J Med 2002;113:112–9. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01150-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosenbloom BE, Weinreb NJ. Gaucher disease: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Oncog 2013;18:163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drelichman G, Fernández Escobar N, Basack N, et al. . Skeletal involvement in Gaucher disease: An observational multicenter study of prognostic factors in the Argentine Gaucher disease patients. Am J Hematol 2016;91:E448–53. 10.1002/ajh.24486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vietri J, Prajapati G, El Khoury AC, et al. . The burden of hepatitis C in Europe from the patients' perspective: a survey in 5 countries. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:16 10.1186/1471-230X-13-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nascimbeni F, Dalla Salda A, Carubbi F. Energy balance, glucose and lipid metabolism, cardiovascular risk and liver disease burden in adult patients with type 1 Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2018;68:74–80. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arends M, van Dussen L, Biegstraaten M, et al. . Malignancies and monoclonal gammopathy in Gaucher disease; a systematic review of the literature. Br J Haematol 2013;161:832–42. 10.1111/bjh.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weinreb NJ, Deegan P, Kacena KA, et al. . Life expectancy in Gaucher disease type 1. Am J Hematol 2008;83:896–900. 10.1002/ajh.21305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hollak CE, Corssmit EP, Aerts JM, et al. . Differential effects of enzyme supplementation therapy on manifestations of type 1 Gaucher disease. Am J Med 1997;103:185–91. 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langeveld M, de Fost M, Aerts JM, et al. . Overweight, insulin resistance and type II diabetes in type I Gaucher disease patients in relation to enzyme replacement therapy. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2008;40:428–32. 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simpson WL, Hermann G, Balwani M. Imaging of Gaucher disease. World J Radiol 2014;6:657 10.4329/wjr.v6.i9.657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alcalay RN, Dinur T, Quinn T, et al. . Comparison of parkinson risk in ashkenazi jewish patients with Gaucher disease and GBA heterozygotes. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:752–7. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosenbaum H, Aharon-Peretz J, Hypercoagulability BB. parkinsonism, and Gaucher disease. Semin Thromb Hemost 2013;39:928–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Attili AF, Carulli N, Roda E, et al. . Epidemiology of gallstone disease in Italy: prevalence data of the Multicenter Italian Study on Cholelithiasis (M.I.COL.). Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karpati T, Cohen-Stavi CJ, Leibowitz M, et al. . Towards a subsiding diabetes epidemic: trends from a large population-based study in Israel. Popul Health Metr 2014;12:32 10.1186/s12963-014-0032-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jaffe DH, Feldman B, Bachrach A, et al. . Healthcare resource utilizaiton in Gaucher disease in Israel. 13th International Congress of Inborn Error of Metabolism (ICIEM). Brazil: Rio De Jeneiro, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pastores GM, Weinreb NJ, Aerts H, et al. . Therapeutic goals in the treatment of gaucher disease. Semin Hematol 2004;41:4–14. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.