Abstract

Objectives and design

This field experiment aimed to compare bowel cancer screening participation rates prior to, during and after a mass media campaign promoting screening, and the extent to which a higher intensity campaign in one state led to higher screening rates compared with another state that received lower intensity campaign exposure.

Intervention

An 8-week television-led mass media campaign was launched in selected regions of Australia in mid-2014 to promote Australia’s National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) that posts out immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) kits to the homes of age-eligible people. The campaign used paid 30-second television advertising in the entire state of Queensland but not at all in Western Australia. Other supportive campaign elements had national exposure, including print, 4-minute television advertorials, digital and online advertising.

Outcome measures

Monthly kit return and invite data from NBCSP (January 2012 to December 2014). Return rates were determined as completed kits returned for analysis out of the number of people invited to do the iFOBT test in the current and past 3 months in each state.

Results

Analyses adjusted for seasonality and the influence of other national campaigns. The number of kits returned for analysis increased in Queensland (adjusted rate ratio 20%, 95% CI 1.06% to 1.35%, p<0.01) during the months of the campaign and up to 2 months after broadcast, but only showed a tendency to increase in Western Australia (adjusted rate ratio 11%, 95% CI 0.99% to 1.24%, p=0.087).

Conclusions

The higher intensity 8-week television-led campaign in Queensland increased the rate of kits returned for analysis in Queensland, whereas there were marginal effects for the low intensity campaign elements in Western Australia. The low levels of participation in Australia’s NBCSP could be increased by national mass media campaigns, especially those led by higher intensity paid television advertising.

Keywords: bowel cancer, screening, mass media, public education, faecal occult blood test, Australia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Objective behavioural outcome data were used from monthly immunochemical faecal occult blood test (iFOBT) invites and returns over the previous 2½ years, compared with those during and after the campaign period.

Adjustment for seasonality and the potential influence of other campaigns, as well examination of the duration of effects.

Lack of a completely unexposed comparison state, however able to compare effects of higher versus lower campaign intensity across entire state populations.

Examined overall campaign effects, rather than for demographic subgroups.

Campaign effects reported are likely to be conservative, as we examined effects only among those invited in the current or past 3 months, not those invited earlier, and not among those who may have accessed screening ‘outside’ of the programme (eg, purchasing iFOBT from pharmacy or obtaining a script from general practitioner for non-National Bowel Cancer Screening Program iFOBT or colonoscopy).

Introduction

Bowel cancer (also known as colorectal cancer) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in high-income nations. For example, it is the third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women, and is also the second most common cause of cancer death in Australia.1 Despite this, 90% of bowel cancer cases can be treated successfully if detected early.2 Screening for bowel cancer via faecal occult blood tests (FOBT) has been shown to reduce bowel cancer mortality by 15%–33%.3 4 An Australian model suggests that with a 40% biennial participation rate, 59 000 deaths are expected to be prevented over the 2015–2040 period, and if a participation rate of 60% could be achieved, an additional 24 800 bowel cancer deaths could be prevented.5

The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council-approved clinical guidelines recommend all asymptomatic people aged of 50–74 years who are average risk should be screened for bowel cancer every 2 years with an FOBT. To facilitate this, the Australian Government commenced the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP) in 2006 where immunochemical FOBT (iFOBT) kits are sent directly to people aged 50–74 at home. A study of people diagnosed with bowel cancer between 2006 and 2008 indicated that compared with non-invitees, those invited to participate in the NBCSP (and particularly those who participated) had less advanced bowel cancers when diagnosed and a lower risk of dying from their bowel cancer.6

Unfortunately participation in the NBCSP among the Australian population has been disappointing, with only 40.9% of those invited taking up the opportunity to be screened by the programme.7 Lack of awareness of bowel cancer and the benefits of screening have been found to contribute to poorer screening rates, including among those invited to participate in the NBCSP.7 8 Of those strategies trialled in Australia and elsewhere to improve screening rates, there is strong evidence for the important role of primary care practitioners’ recommendations to undergo screening in determining whether a patient is screened.9 Using media education (postcards, letters) within primary care and enhancing primary care practice electronic medical records to include reminder systems can also improve screening rates.10 Outside primary care, culturally adapted group education sessions and multicomponent interventions (such as education sessions, videos and special events) have been found to increase screening rates,11 while telephone outreach modestly increases screening.12 Financial support and one-on-one education have been found to be less effective than group education.11 As the delivery of each of these interventions relies on practitioner, community or cultural group initiatives, they are likely to have limited population reach and so are limited in their capacity to drive increases in the overall population screening rate.

Increasing the population screening rate will likely require interventions delivered to the broad population through mass dissemination techniques. There is some evidence that tailoring of mail-based interventions with FOBT invitation modestly improves screening above standard FOBT mail-out,12 while one study has shown celebrity endorsements can increase screening rates.13 The few studies that have examined the effectiveness of mass media bowel cancer screening campaigns have shown that they can increase population screening rates,11 but describe the effects as moderate and short lived. This is consistent with the pattern of effects found for mass media campaigns for other health behaviours,14 such as for smoking cessation.15

Research into the effectiveness of mass media in changing other health behaviours has shown that success is closely tied to the extent and timing of exposure, with time-limited effects for ‘one-off’ campaigns and less impact if there is low message repetition and narrow population exposure.16 Nonetheless, these studies have shown that small effects can lead to substantial impact on population behavioural change due to exposing many individuals within a population. Consistent with this, a recent study found that specialist referrals increased following a one-off 7-week television-led bowel cancer detection campaign in the UK, and that the increase lasted for 3 months postcampaign.17 18 Illustrating the importance of the extent of population exposure, another study found that as past year exposure to screening information increased from news media and the television-led ‘Screen for Life’ campaign, levels of screening participation rose.19 One non-televised medical practice based campaign in the UK (leaflets, DVDs, posters, bookmarks along with practice reminder letters and health professional education materials) was found to increase health professional visits and referrals to FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, but not more so than the comparison group that implemented only the practice reminder letters and health professional education.20 Another non-televised campaign in the USA relying on billboards, posters and articles sent to local newspapers, and brochures and posters in clinics produced no differences in bowel cancer screening rates among those in counties exposed to it compared with those in control counties.21 The limited effect of these campaigns is likely due to the low population reach of these types of non-televised campaign elements.

As there had been very few widespread Australian television-led mass media campaigns to promote the NBCSP and use of FOBT kits mailed to eligible people’s homes, Cancer Council Australia (CCA) launched a mass media campaign in mid-2014. The campaign included a 30 second television commercial (TVC) which aired in three Australian states: all of Queensland, metropolitan Adelaide in South Australia and regional Victoria. Other supportive elements of the campaign had national exposure, including a print, digital and online strategy (full-page print advertisement in Prevention magazine; internet search optimisation; native digital content advertising; digital video advertising; website sponsorship) and 4 minute televised editorial segments on morning show programmes. The primary campaign objective was to increase the number of people aged 50–74 who completed an NBCSP FOBT.

This study aims to identify if NBCSP FOBT completion and return rates increased during and after the CCA bowel cancer screening mass media campaign and the extent to which the higher intensity paid television advertisements led to higher screening rates. This will be achieved by comparing the rate of FOBT completion over the 2½-year period prior to the campaign with rates during and after the campaign. The impact of campaign intensity will be examined by comparing return rates over time in the state with complete exposure to all of the campaign elements including paid 30-second television advertising (Queensland) with a comparison state (Western Australia, WA) that was only exposed to the lower intensity supportive elements (see following link for interactive map of the states and territories of Australia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/States_and_territories_of_Australia).

Method

NBCSP register data

The NBCSP has had a gradual introduction (table 1), with full implementation as a 2 yearly programme to be complete by 2020. The test used by the NBCSP is an immunochemical test requiring the collection of two samples, which is a non-invasive test that can detect microscopic amounts of blood in a bowel motion, which might indicate a bowel abnormality, such as a polyp, an adenoma or cancer. Once fully implemented, eligible Australians will be sent an iFOBT screening kit and invited to screen every 2 years between their 50th and 74th birthdays. More information about eligibility is available at: http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/bowel-campaign-home.

Table 1.

Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program implementation

| Start date | Ages invited |

| August 2006 | 55, 65 |

| July 2008 | 50, 55, 65 |

| July 2013 | 50, 55, 60, 65 |

| January 2015 | 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 74 |

| January 2016 | 50, 55, 60, 64, 65, 70, 72, 74 |

| January 2017 | 50, 54, 55, 58, 60, 64, 68, 70, 72, 74 |

| January 2018 | 50, 54, 58, 60, 62, 64, 66, 68, 70, 72, 74 |

| January 2019 | 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60, 62, 64, 66, 68, 70, 72, 74 |

To participate, those invited by the NBCSP need to complete the screening test and post it in the provided postpaid envelope to the NBCSP pathology laboratory for analysis within 14 days of completing the test. Results are then sent to the participant, their nominated primary healthcare practitioner and to the NBCSP Register. Those with a positive screening result, indicated by blood in the stool sample, are advised to consult their primary healthcare practitioner to discuss further diagnostic assessment which in most cases will be a colonoscopy.6

De-identified NBCSP monthly data from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2014 from Queensland and WA were obtained. The data included the number of NBCSP invitations sent out and the number of NBCSP kits returned for analysis within each month and state.

Participant involvement

At the campaign development and refinement stage (October 2013), potential NBCSP eligible members of the public were consulted through a series of focus groups (four groups of people aged 50–54 years and four groups of people aged 55–65 years across metropolitan and regional areas). These groups were shown the campaign materials and responded to these through a guided discussion. They discussed perceived salience and relevance of the message, message understanding and perceived credibility and likely impact on behavioural change. A number of additions and refinements were made to the campaign materials in response to this feedback.

Patients were not involved in the design or conduct of the study as this research involved secondary analysis of real-world data collected by the NBCSP. We completed a standard data request for the invite and kit return data for this study from the Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare (https://www.aihw.gov.au/our-services/data-on-request). In the NBCSP information booklet that is sent to participants with the FOBT kit, it stated, ‘Your personal details will be used to: monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the program and its impact on the incidence of bowel cancer.’ This information booklet also detailed how participants can opt out of the NBCSP if they would like to. The data quality statement for the NBCSP can be found at http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/668817.

CCA mass media campaign

The mass media campaign, run by CCA with Australian government funding, aimed to increase awareness of the preventability of bowel cancer when detected early and to encourage adults aged 50–74 years to participate in the NBCSP when invited. The proposed creative concepts went through extensive qualitative developmental testing to ensure that they were relevant and likely to be effective with the target audience.22 A 30-second TVC featured real people who prematurely lost loved ones to bowel cancer reflecting on how much they missed them and how preventable bowel cancer is if detected early. The TVC informed people that ‘Bowel cancer kills 75 Australians every week’, that ‘If detected early, 90% of bowel cancers are cured’ and asked ‘Are you 50 or over? Do the test. It could save your life’. The TVC closed by encouraging people to visit a campaign microsite (bowelcancer.org.au) and Cancer Council Helpline11 13 20 to find out more.

The TVC aired from 1 June to 26 July 2014 and was estimated by media buyers to reach around three-quarters of the target audience approximately 10–11 times.23 It was broadcast on Channel Seven, the most popular free-to-air Australian network channel, across the entire state of Queensland. It was also released nationally as a Community Service Announcement and achieved approximately $AU40 000 in bonus airtime nationally from the Seven Network. A 4-minute televised advertorial (ie, an interview segment within a morning show TV programme) was also broadcast nationally, being shown 21 times (in The Morning Show and The Daily Edition, which had high potential audience reach among 50+ years old). A full-page advertisement and editorial coverage were included in the July edition of Prevention magazine, which also had good potential audience reach among 50+ year olds. General practitioners (GPs) were also targeted with advertisements in the Medical Journal of Australia and Australian Family Physician. Finally, the campaign included online promotion using Google Adwords search, YouTube, TrueView video, Digital native advertising, multichannel network partnership and Yahoo!7 Display/Video.

Statistical analyses

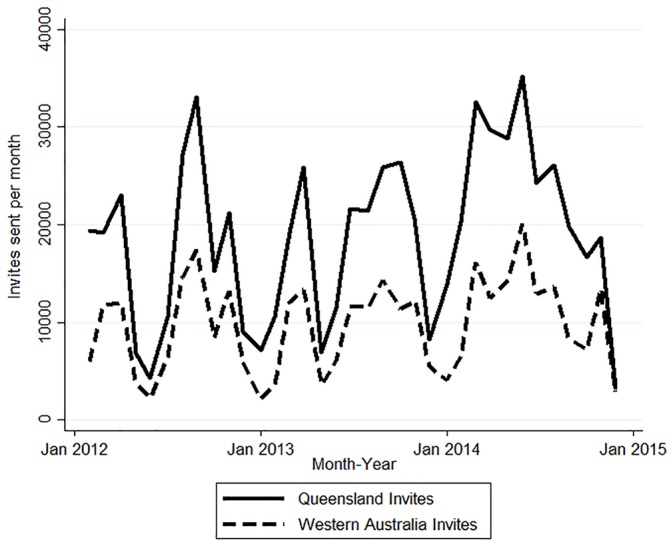

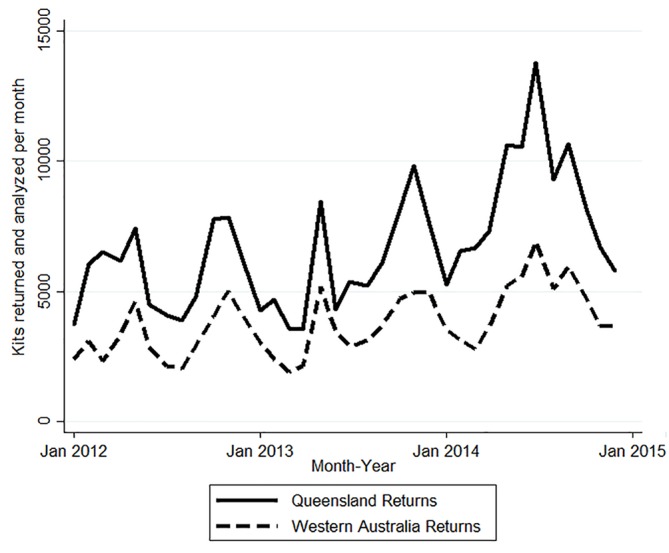

Our outcome measure was the number of FOBT kits returned to the NBCSP for analysis per month. This outcome showed no evidence of autocorrelation, however, it was overdispersed (mean=5234; variance=5 769 399) and so negative binomial regression was used in preference to Poisson regression. The pattern of the data was examined in preliminary analyses to examine if there was any seasonality. This examination revealed a lower number of kits were returned for analysis during each January to February, due to the lower number of invitations that were sent out during the summer high temperature months (ie, from December to February). In addition, higher numbers of kits were returned for analysis around May, October, November and December each year, due to greater numbers of invitations sent out in March, April, September, October and November each year to compensate for lower numbers in the high temperature months (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Monthly number of invitations sent, January 2012 to December 2014, by state.

Figure 2.

Monthly number of kits returned and analysed, January 2012 to December 2014, by state.

The Jodi Lee Foundation also funded a separate television-led bowel cancer screening campaign with additional online and news supportive media in September 2014 in metropolitan and rural Queensland and metropolitan WA. An indicator variable was constructed to denote when that campaign was on air and for 2 months after it aired (September to November 2014), so it could be included in analyses as a covariate.

We constructed a bivariate variable to denote when the CCA campaign was on air plus 2 months after the end of the broadcast period (ie, ‘0’ for non-campaign months (used as the reference) and ‘1’ for June, July, August, September 2014). Previous research has indicated the effects of behavioural change campaigns may last for up to 2–3 months after broadcast ends.24–26 We limited the potential effect of the CCA campaign to only 2 months postbroadcast to avoid substantial overlap with the Jodi Lee campaign that began in mid-September 2014.

Similar to prior research examining the effects of mass media campaigns on screening rates,27 negative binomial regression analyses were conducted to compare rates of kits returned for analysis over time and in both states each year. To enable detection of the effects prompted by the campaign on return rates among those recently sent an invitation, we used the average monthly number of people invited to do the FOBT test in the current and past 3 months as the offset term.28 29

Seasonally adjusted models were run, with additional adjustment for the month associated with the Jodi Lee campaign and the 2 months after that campaign went off air (September to November 2014). The first set of negative binomial models examined the overall effect of the CCA campaign in Queensland and WA together (including a state indicator as a covariate). The second set of models examined whether there was an interaction between state and campaign, with subsequent models categorising the state and campaign period separately (1=WA, non-campaign months; 2=WA, campaign months; 3=QLD, non-campaign months; 4=QLD, campaign months), to examine state-specific return rates and rate ratios. Sensitivity analyses examined effects of specifying the duration of CCA campaign effect as lasting up to 1 month after broadcast, instead of up to 2 months after broadcast. Examination of the duration of effects beyond 2 months was not possible due to overlap with the Jodi Lee campaign.

Results

Over both Queensland and WA, the CCA campaign was associated with an increase in the number of returned kits among those invited in the current and past 3 months (Rate Ratio (RR) 1.15, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.27, p<0.01). The seasonally adjusted average number of monthly kits returned and analysed during non-CCA campaign months were 6631 in QLD and 3805 in WA and during CCA campaign months were 7945 in QLD and 4213 in WA. As table 2 shows, the rate of kits returned for analysis increased by 20% in Queensland during the months of the national CCA campaign and up to 2 months after broadcast, but only showed a tendency to increase in WA (11%, p=0.087). Given the similar direction of movement (although non-significant in WA), there was no indication of an interaction between state and the CCA campaign (X2=1.07, p=0.300) and there was no significant difference between the Queensland and WA increase in rate of change (RR-difference 1.08, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.26, p=0.300). The sensitivity analyses examining the length of campaign effects indicated that the overall campaign effect was non-significant when configured to last for only 1 month after broadcast (IRR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.22, p=0.062), however, the effect for Queensland was significant by then (IRR 1.15, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.33, p=0.046).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted NBCSP return rates, average monthly FOBT kits returned for analysis, and rate ratios associated with the Cancer Council Australia bowel cancer screening campaign, in Queensland and Western Australia from January 2012 to December 2014

| Unadjusted monthly return rate % Unadjusted average monthly kit returns† (invitations‡) |

aAdjusted§ return rate % (95% CI) Adjusted§ kit returns (95% CI) Adjusted§ rate ratio associated with the CCA campaign (95% CI) |

|||

| QLD | WA | QLD | WA | |

| Non-campaign months | 34.8% 6243 (17 919) |

39.1% 3595 (9203) |

34.3% (31.3% to 37.7%) 6631 (6372 to 6890) 1 |

38.6% (35.3% to 42.2%) 3805 (3638 to 3973) 1 |

| CCA campaign months¶ | 38.1% 11 057 (29 000) |

39.5% 5883 (14 894) |

41.2% (35.5% to 47.7%) 7945 (7035 to 8855) 1.20 (1.06 to 1.35)** |

42.7% (37.2% to 49.2%) 4213 (3773 to 4652) 1.11 (0.99 to 1.24)* |

*P<0.10, **P<0.01.

†Average monthly FOBT kits returned and analysed.

‡Average monthly number of people invited to screen over the current and past 3 months.

§Adjusted for seasonality and Jodi Lee Campaign (September to November 2014).

¶Campaigns months=June, July, August, September 2014 (months the CCA campaign was on air plus 2 additional months after campaign end).

FOBT, faecal occult blood test; QLD, Queensland; WA, Western Australia.

Discussion

Compared with non-campaign months, the television-led CCA campaign was found to increase the numbers of age-eligible people returning their NBCSP kits for analysis by 15% across these two Australian states, and by 20% in Queensland where the paid television advertisements were broadcast. This increase occurred during the months of the campaign and for 2 months following the end of the campaign. The findings of this study build on previous research that has indicated bowel cancer screening campaigns can increase bowel cancer screening rates.11 The higher intensity campaign that included the paid television advertisement in Queensland that reached around 75% of the target audience approximately 10–11 times, plus the supportive media (ie, 21 4-minute advertorials, plus digital media) generated a substantial increase in the rate of kits returned for analysis. However, within WA where only the supportive media was used, there was a smaller and non-significant increase. The interaction analysis indicated that the increased rate of return in Queensland was not significantly different from that in WA, suggesting that this lower intensity media mix in WA led to an increase in return rates, but this increase was less reliable and smaller in magnitude.

Among the 7.0% who tested positive on the FOBT in 2014 and who had a follow-up diagnostic assessment,30 0.7% were ultimately confirmed cancers, 2.4% were suspected cancers, 6.9% were advanced adenomas and 7.1% were non-advanced adenomas and 23.2% were polyps awaiting histopathology. Our results suggest that the Queensland CCA campaign mix that included the paid television advertising component was associated with an extra 1314 (95% CI 663 to 1965) kits being returned per month, meaning that 5256 (95% CI 2652 to 7860) extra kits were returned in Queensland over the 2 campaign months and 2 months postcampaign. Extrapolating these figures, the CCA campaign is estimated to have led directly to an extra 368 (range 186–550) people who tested positive on the FOBT. With around 73.4% of these having follow-up diagnostic assessment (n=270, range 137–404),30 the CCA campaign in Queensland may therefore have led directly to the detection of around an extra 2 (range 1–3) people with confirmed cancer, an extra 6 (range 3–10) with suspected cancer, an extra 19 (range 9–28) people with advanced adenomas, an extra 19 (range 10–29) people with non-advanced adenomas and an extra 63 (32–94) people with polyps awaiting histopathology, in that state alone.

It is important to note that this clinically significant result is due to a single 2-month campaign burst in one state and would be magnified if the campaign was rolled out nationally and repeated several times each year. Similar campaigns could lead to fivefold increases in these population effects, given Queensland only accounts for 20% of the Australian population. There is also a cumulative benefit given monitoring records show that 76.9% of these people will do the test again when next invited.31 These findings highlight the importance of widespread population exposure, which is mostly reliably facilitated through paid television advertisement broadcasts combined with other supportive media channels, especially for this older demographic which still consumes many hours of television content.32 It is possible those studies which found little impact of non-televised campaigns21 may have suffered from inadequate population penetration.

Study limitations and strengths

There are several study limitations. First, we did not have an unexposed comparison state, given the presence of other public relations and lower level campaign activity in other Australian states. In addition, our analyses were limited to examining overall effects of campaign presence and were unable to examine the impact of the campaign by age, gender, location or socioeconomic status (SES) as some previous work on the effects of mass media cancer screening campaigns has done.27 33 Future research should aim to examine effects by SES and location, gender and age group, given the evidence that lower SES and remote people, males and younger age groups (50–59 years) are less likely to participate in the NBCSP.30

In addition, this study only examined the effect this campaign had on the NBCSP kit return rates from those who were invited in the current or past 3 months (our offset term). A minority retain the uncompleted test at home for longer than this time period, so kit returns due to the campaign could have been higher. Our offset term was therefore cautious. In Australia, there is a significant proportion of people aged 50–74 who access screening ‘outside’ of the NBCSP, either by purchasing an FOBT from a pharmacy, obtaining a script from their GP for a non-NBCSP FOBT or by colonoscopy.23 Thus, while this campaign may have had a broader effect on bowel cancer screening, the present results are limited to effects only on those recently invited to complete an FOBT through the NBCSP. Finally, the estimated proportions that tested positive and undertook follow-up assessment are based on information reported back by pathology providers to the NBCSP Register. As reporting back to the NBCSP Register is not mandatory, the data are incomplete and may be an under-representation.30 The level of under-reporting is unknown. Therefore, it is possible the number of people who tested positive on the FOBT and who completed follow-up assessment may be higher than the extrapolated numbers described above, meaning the outcomes for those assessed (ie, proportion of confirmed cancers, suspected cancers, adenomas) likely represent an underestimate.

The strengths of this research include the use of an objective behavioural outcome to examine the impact of the campaign and statistical adjustment for the number of people who were invited to complete the FOBT kit within the current and past 3 months. Confidence in these findings is also strengthened by adjusting for seasonality and the potential influence of the presence of the other campaigns, as well as testing for the length of effects in the sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

Overall this study suggests that the low levels of participation in the NBCSP may be increased by future national mass media campaigns, especially those led by paid television advertising. Regularly repeated broadcasting of wide-reaching mass media bowel cancer screening campaigns could educate new cohorts about the NBCSP as they age into eligibility, and remind those already eligible about the risks of bowel cancer and the benefits of screening, helping to maximise participation and ultimately prevent many thousands of bowel cancer deaths.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Programme for providing access to FOBT data by state to enable the analysis in this paper and for reviewing the results of this analyses.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: None declared.

Contributors: SJD and MAW contributed to the conception and design of the study. KB contributed to the acquisition of data and interpretation of the work. SJD, MJS and MAW contributed to data analysis and interpretation. SJD drafted and revised the paper, while MAW, KB and MJS revised the paper. All authors provided approval for the final version of the paper to be published.

Funding: This study was funded by Cancer Council Victoria.

Competing interests: SJD, KB and MAW are employed as researchers by Cancer Council Victoria, a state-based organisation affiliated with Cancer Council Australia which developed and ran the mass media campaign. MJS and all other authors have no other competing interests.

Ethics approval: The AIHW follows Australian research ethics guidelines with data and considers whether the data request requires ethical approval, and they deemed that our data request did not require ethics approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The iFOBT invite and kit return data used in this study were secondary and originally obtained via a standard data request from the Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (https://www.aihw.gov.au/our-services/data-on-request). The data can be obtained directly from the Australian Government Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) on request (https://www.aihw.gov.au/our-services/data-on-request).

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2017. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017. Cancer Series no. 101 Cat. No. CAN 100. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health. About bowel screening Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health. 2014. http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/about-bowel-screening (cited 3 November 207).

- 3. Department of Health and Ageing. The Australian bowel cancer screening pilot program and beyond: final evaluation report. Canberra: DoHA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lieberman D. Progress and challenges in colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2115–26. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lew JB, St John DJB, Xu XM, et al. . Long-term evaluation of benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of the national bowel cancer screening program in Australia: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e331–40. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30105-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Analysis of bowel cancer outcomes for the National bowel cancer screening program. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014. Cat. no. CAN 87. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National bowel cancer screening program: monitoring report 2018. Canberra, Australia: Australian institute of health and welfare: Cancer Series, 2018. Cat. no CAN 112 Contract No.: ISBN: 978-1-76054-333-4. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duncan A, Wilson C, Cole SR, et al. . Demographic associations with stage of readiness to screen for colorectal cancer. Health Promot J Austr 2009;20:7–12. 10.1071/HE09007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zajac IT, Whibley AH, Cole SR, et al. . Endorsement by the primary care practitioner consistently improves participation in screening for colorectal cancer: a longitudinal analysis. J Med Screen 2010;17:19–24. 10.1258/jms.2010.009101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alberti LR, Garcia DP, Coelho DL, et al. . How to improve colon cancer screening rates. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2015;7:484–91. 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i12.484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martini A, Morris JN, Preen D. Impact of non-clinical community-based promotional campaigns on bowel cancer screening engagement: an integrative literature review. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1549–57. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Courtney RJ, Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher RW, et al. . Community approaches to increasing colorectal screening uptake: a review of the methodological quality and strength of current evidence. Cancer Forum 2012;36:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cram P, Fendrick AM, Inadomi J, et al. . The impact of a celebrity promotional campaign on the use of colon cancer screening: the Katie Couric effect. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1601–5. 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010;376:1261–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control 2012;21:127–38. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Durkin S, Wakefield M. Commentary on Sims et al. (2014) and Langley et al. (2014): mass media campaigns require adequate and sustained funding to change population health behaviours. Addiction 2014;109:1003–4. 10.1111/add.12564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bethune R, Marshall MJ, Mitchell SJ, et al. . Did the ‘Be Clear on Bowel Cancer’ public awareness campaign pilot result in a higher rate of cancer detection? Postgrad Med J 2013;89:390–3. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peacock O, Clayton S, Atkinson F, et al. . ‘Be Clear on Cancer’: the impact of the UK National Bowel Cancer Awareness Campaign. Colorectal Dis 2013;15:963–7. 10.1111/codi.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooper CP, Gelb CA, Hawkins NA. How many “Get Screened” messages does it take? Evidence from colorectal cancer screening promotion in the United States, 2012. Prev Med 2014;60:27–32. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tiffany C, Perry C, Thurston M, et al. . Improving awareness and uptake rates in bowel cancer screening across cheshire and merseyside. Evaluation of a bowel cancer screening awareness campaign for cheshire and merseyside public health network. ChaMPs: University of Chester, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krok-Schoen JL, Katz ML, Oliveri JM, et al. . A media and clinic intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening in ohio appalachia. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–9. 10.1155/2015/943152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michael Murphy Research. Bowel cancer screening recruitment strategy. Report of qualitative testing of bowel screening television commercials. Melbourne, Australia: Cancer Council Victoria, 2013. 8 November. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scalzo K, Mullins R. Evaluation of the 2014 national bowel cancer screening program communication campaign. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, Prepared for: Cancer Council Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, Yong HH, et al. . Effects of mass media campaign exposure intensity and durability on quit attempts in a population-based cohort study. Health Educ Res 2011;26:988–97. 10.1093/her/cyr054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dunlop S, Cotter T, Perez D, et al. . Televised antismoking advertising: effects of level and duration of exposure. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e66–73. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dunlop SM, Dobbins T, Young JM, et al. . Impact of Australia’s introduction of tobacco plain packs on adult smokers’ pack-related perceptions and responses: results from a continuous tracking survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005836 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anderson JO, Mullins RM, Siahpush M, et al. . Mass media campaign improves cervical screening across all socio-economic groups. Health Educ Res 2009;24:867–75. 10.1093/her/cyp023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0 Australian demographic statistics. TABLE 55. Estimated resident population by single year of age, Western Australia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0 Australian demographic statistics. TABLE 53. Estimated resident population by single year of age, Queensland. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. National bowel cancer screening program monitoring report 2017. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017. Cancer series no.104. Cat. no. CAN 103. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. Cancer screening in Australia by small geographic areas 2015-2016. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roy Morgan Research. 1 in 7 Australians now watch no commercial television, nearly half of all broadcasting reaches people 50+, and those with SVOD watch 30 minutes less a day. Melbourne, Australia: Roy Morgan Research, 2016. Press release, 1st February. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun J, March S, Ireland MJ, et al. . Socio-demographic factors drive regional differences in participation in the national bowel cancer screening program - An ecological analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018;42:92–7. 10.1111/1753-6405.12722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.