Abstract

We present a rare cause for cutaneous furuncular myiasis in a 55-year-old British traveller returning from Uganda. Initially presenting with what appeared to be a cellulitic furuncle on her forehead, she returned to the emergency department 3 days later with extensive preseptal periorbital swelling and pain. Occlusive treatment with petroleum jelly was applied and one larva manually extracted and sent to London School of Tropical Medicine for examination. It was identified as Lund’s Fly (Cordylobia rodhaini), a rare species from the rainforests of Africa with only one other case reported in the UK since 2015. Ultrasound imaging identified another larva, necessitating surgical exploration and cleaning. The lesion subsequently healed completely and the patient remains well.

Keywords: tropical medicine (infectious disease), oral and maxillofacial surgery, global health, travel medicine

Background

Myiasis is an infestation caused by larvae of two-winged flies, commonly referred to as maggots.1 It is widely observed in tropical countries. Though less well known to the UK, myiasis is the fourth most common travel-associated skin disease; the cutaneous form being the most frequently encountered.2 Increasing international travel raises the need for clinicians to be aware of such conditions. The diagnosis is clinical but relies on a good travel history. Although self-limiting, active removal of larvae may be necessary to alleviate patients’ symptoms and prevent unnecessary antibiotic treatment. Management involves occlusive methods and manual extraction, as well as surgical intervention. Knowledge of the life cycles of larvae is important for safe extraction.2

This case is unusual because of the rare presentation on the scalp and the species of Cordylobia identified that is an infrequently described cause of human myiasis.2

Case presentation

A 55-year-old woman presented to the emergency department in the UK. The patient had recently returned from a trek in the tropical rainforest of Kibale National Park, Uganda. She had developed a furuncular lesion on the forehead with associated swelling. She was seen 9 days after onset of symptoms in the department by a maxillofacial core trainee, and it was felt to be a cellulitis related to a possible insect bite. As she was systemically well, she was discharged with oral flucloxacillin, 500 mg four times per day, for 5 days. She returned 3 days later as the swelling had extended periorbitally, but preseptally, and was now associated with sharp, shooting pains (figure 1). The furuncular lesion in the midline of the forehead measured 1 cm in diameter with a serous discharge. There was no pus or collection to drain. She was admitted under the Maxillofacial Surgery team, discussed with Microbiology and commenced on intravenous flucloxacillin, 2 g four times daily, which continued throughout her 4 day inpatient stay.

Figure 1.

Swelling and erythema of the patient’s forehead and close-up of the punctum with petroleum jelly over it.

Investigations

Full blood count, CRP, liver function tests, blood cultures, blood films for malaria, arbovirus testing and Rickettsia serology all proved unremarkable, except for a raised C-Reactive Protein (CRP) of 22.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential was facial cellulitis, possibly secondary to an insect bite.

Treatment

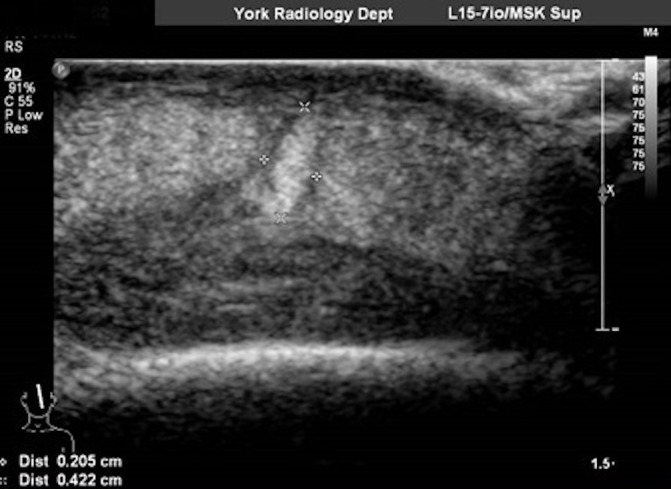

Following occlusive treatment with petroleum jelly (figure 1), one live larva was manually extracted and sent to London School of Tropical Medicine for examination (figure 2). The larva was identified as Lund’s fly (Cordylobia rodhaini), a rarely seen species from the rainforests of Africa.3 Ultrasound imaging identified a possible other larva (figure 3), and the patient elected to undergo surgical exploration and cleaning of the wound.

Figure 2.

Cordylobia rodhaini larva, early third instar, extracted from patient’s forehead.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound image showing larva.

Outcome and follow-up

On follow-up, the patient remains well and her wound has fully healed.

Discussion

The most common causes of human myiasis are Cordylobia anthropophaga (the Tumbu fly), from Africa, and Dermatobia hominis (the human botfly) from the Americas.2 C. rodhaini (the Lund’s fly) is rarely reported, with only 14 cases published worldwide since 1970.4 According to the London School of Tropical Medicine they have seen only one other case since 2015 (compared with 27 Tumbu fly larvae).5 Similar to C. anthropophaga, C. rodhaini is found in sub-Saharan Africa but in rainforest climates. It accidentally infests humans, preferring thin-skinned mammals such as rodents. The larva is activated by body heat, hatches and invades the skin. Larvae mature under the skin, forming a furuncular lesion, and exit after 8–12 days.6 After falling to the ground the fly emerges and the life cycle continues.

Similarly to the Tumbu fly, the Lund’s fly may lay eggs on damp clothing, rather than the skin.1 Consequently it is very unusual for patients to present with lesions affecting the face. Commonly, they present with lesions on the trunk and thighs, often with multiple furuncles. It has been noted that Lund’s fly causes more severe and painful infestations than those of the Tumbu fly, although they also tend to be smaller. Inflammatory change around the furuncle is common, mimicking soft tissue bacterial infections such as cellulitis. Regional lymphadenopathy or malaise may be seen in the presence of multiple lesions; however, the disease is usually uncomplicated and self-limiting. The most commonly reported complication of furuncular lesions is secondary bacterial infection though most lesions fully heal, occasionally leaving scars. Ivermectin use (both topical and oral) has been reported, particularly in cases of cavitatory myiasis but systemic therapy is rarely necessary; its use also brings with it the risk of the larvae dying in situ leading to further inflammation.1

The treatment for myiasis varies slightly depending on the species involved and stage of the life cycle. Management largely involves occlusive methods (often with petroleum jelly/dressings) and manual extraction. This method should not be restrictive because this may asphyxiate the larva before it is able to migrate out of the skin. If occlusion fails, local anaesthetic can be administered and an incision made to widen the punctum and remove the maggot, followed by primary wound closure.7 The larva should not be forcibly removed through the central punctum because its tapered shape with rows of spines and hooks anchor it to the subcutaneous tissue. It is important to remove all parts of the larva to prevent a foreign body reaction and secondary infection. Equally, the larva should not be burst as this can cause a local inflammatory reaction. A travel history may help the clinician to recognise the fly, which can be important for extraction—the shape of the botfly larva changes at different stages, making the risk of breaking the larva higher.

In our patient’s case, diagnosis was initially delayed by the site of the lesion. Although considered, myiasis of the forehead was considered very unlikely. A careful history revealed that our patient wrapped her hair in a damp towel that had been left outside for a time. There is only one other reported case of myiasis of the face in the UK. A British traveller returning from Angola, Southern Africa presented with a furuncular lesion associated with the left eye. This was initially misdiagnosed as dacryocystitis.8 Delays in diagnosis can lead to more discomfort for the patient, inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing and potentially complications if the larva doesn’t self-evacuate. As such, a key learning point from our case is not to question the plausibility of the diagnosis of myiasis in the returning traveller without thoroughly checking the history.

Patient’s perspective.

I returned to hospital after phoning up to say my symptoms had got worse/my face more swollen and I was in great pain 3 days later. I was seen quickly and admitted to the Maxillofacial Ward 1 where they were just great—extremely helpful. I have previously been used to having lots of things running through my mind, ideas particularly would often pop out (but) maggots were a first!

Also, a friend of my son who joined us in Uganda had the same infestation on his back when he left to come home to UK, but the walk-in centre in London where he lives did not believe the lump on his back was anything more than an infected bite. He also had a maggot which came out when he took the Elastoplast off!

Learning points.

A good travel history is essential to help formulate an appropriate differential diagnosis in the returned traveller.

Myiasis should be considered in any traveller returning with a furuncular skin lesion, even when at an unusual site (eg, the forehead).

Primary treatment involves occluding the punctum to encourage the larva to migrate out of the skin.

Surgical exploration and antibiotics are only necessary when there is true superadded infection requiring debridement/antimicrobial therapy. Where the larva does not self-extricate, surgery may also be required.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patient for her help and support in preparing this case report.

Footnotes

Contributors: NW, first author, edits and reviews. FS edits, reviews and corresponding author. DM edits and reviews. NB edits and reviews.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1. Francesconi F, Myiasis LO, Review L. American Society for Microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2012;25(no. 1):79–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robbins K, Khachemoune A. Cutaneous myiasis: a review of the common types of myiasis. Int J Dermatol 2010;49:1092–8. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pezzi M, Cultrera R, Chicca M, et al. . FUruncular myiasis caused by cordylobia rodhaini (diptera: Calliphoridae): A case report and a literature review. J Med Entomol 2015;52:151–5. 10.1093/jme/tju027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grassi V, Butterworth JW, Latiffi L. Cordylobia rodhaini infestation of the breast: Report of a case mimicking a breast abscess. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;27:122–4. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Personal Communication. Telephone Conversation March 2018 between F Shahi and Laboratory Staff, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- 6. Tamir J, Haik J, Schwartz E. Myiasis with lund’s fly (cordylobia rodhaini) in travelers. J Travel Med 2006;10:293–5. 10.2310/7060.2003.2732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blaizot R, Vanhecke C, Le Gall P, et al. . Furuncular myiasis for the Western dermatologist: treatment in outpatient consultation. Int J Dermatol 2018;57:227–30. 10.1111/ijd.13815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee EJ, Robinson F. Furuncular myiasis of the face caused by larva of the Tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga). Eye 2007;21:268–9. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]