Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the association between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression in patients with acne.

Design

This was a meta-analysis in which the standardised mean difference (SMD) and the relative risk (RR) were used for data synthesis employing the random-effects model.

Setting

Studies were identified via electronic searches of PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library from inception up to 28 December 2017.

Participants

Patients with acne.

Interventions

Studies comparing isotretinoin with other interventions in patients with acne were included.

Results

Twenty studies were selected. The analysis of 17 studies showed a significant association of the use of isotretinoin with improved symptoms compared with the baseline before treatment (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI −0.51 to −0.15, p<0.05; I 2=76.6%, p<0.05)). Four studies were related to the analysis of the risk of depression. The pooled data indicated no association of the use of isotretinoin with the risk of depressive disorders (RR=1.15, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.21, p=0.14). The association of the use of isotretinoin with the risk of depressive disorders was statistically significant on pooling retrospective studies (RR=1.39, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.84, p=0.02), but this association was not evident on pooling prospective studies (RR=0.85, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.21, p=0.86).

Conclusions

This study suggested an association of the use of isotretinoin in patients with acne with significantly improved depression symptoms. Future randomised controlled trials are needed to verify the present findings.

Keywords: acne, depression, isotretinoin, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Most included studies were prospectively designed, and the quality of included studies was largely moderate to high.

The heterogeneity was explored by sensitivity, subgroup and meta-regression analyses.

The small sample sizes of some included studies might have limited the statistical power and increased the chance of missing small effects.

No randomised controlled trial was available so far, which was a major drawback for studies on this topic.

The treatment duration, drug dose and depression scale varied between different studies.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit of the face, neck, chest and back.1 As a pleomorphic skin disease, it may present as non-inflammatory lesions (open and closed comedones) or inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules or nodules).2 It is the most common skin disease around the world, with an estimated prevalence of 70%–87%.3 The economic burden of acne is substantial. The cost is estimated to exceed $1 billion per year in USA for direct acne therapy, with $100 million spent on various acne products.4 Acne vulgaris may cause cosmetic defects and significantly impact the quality of life.5 It may provoke a wide range of mental problems, including depression, anxiety, poor self-esteem, social phobia and even suicidal attempts.6

The optimal treatment approach depends on the morphology and severity of acne. Mild cases are suggested to be treated with topical retinoids. For moderate cases, systemic drugs are always needed, including oral antibiotics, hormonal therapy and oral retinoids. However, for severe or resistant moderate acne, isotretinoin is the treatment of choice.1 2 4 7 Isotretinoin is a vitamin A-derivative 13-cis-retinoic acid, which is the most effective therapy for acne to date. It targets all four processes during acne development, including normalisation of follicular desquamation, reduction of sebaceous gland activity, inhibition of the proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes and anti-inflammatory effects.2 7 8 The meta-analysis suggested that isotretinoin cured around 85% of patients after an average treatment course of 4 months.9

Depressive disorders are highly prevalent in the Western world. The lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorders in USA and Western Europe is around 13%–16%.10 The frequency of depressive disorders during the use of isotretinoin varies from 1% to 11%.11 Theoretically, effective treatment may lead to an improvement in depressive symptoms of patients with acne. However, the use of systemic isotretinoin itself may potentially increase the risk of depression.12 Experimental studies showed that isotretinoin could affect the central nervous system and was involved in the pathogenesis of depression.13 However, some researchers disputed that the risk was extremely small and might be influenced by the background risk or non-drug confounding factors.12 The evidence for this controversy remained incomplete and unclear. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to explore the association between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression among patients with acne. Further, whether this relationship differed in patients with specific characteristics was also explored.

Methods

Literature search

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline was followed to conduct this meta-analysis.14 A literature search for articles published between May 1984 and 28 December 2017, was performed using PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Library. The following groups of keywords were used in the search: (‘depression’ OR ‘depressive’) AND ‘acne’ AND ‘isotretinoin'. The details of searching strategy in PubMed are presented in online supplementary 1. Also, a manual search of references listed in included studies and published reviews were also performed to search for potentially eligible studies. The language was restricted to English.

bmjopen-2018-021549supp001.pdf (19.7KB, pdf)

Selection criteria

Studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) Being a randomised controlled trial (RCT), prospective or retrospective study, nested case–control study or population-based case–control study. (2) Comparing the outcomes before and after the use of isotretinoin in patients with acne, or comparing isotretinoin with other treatment regimens in patients with acne. (3) Presenting the change in depressive symptoms measured using a continuous depression scale,15 or reporting the number of patients with depression before and after the use of isotretinoin, or directly presenting the relative risk (RR), OR or HR between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts for eligibility and extracted data in standardised electronic tables. The following data were extracted from included studies: publication year, author, study design, sample size, participant sex and age, severity of acne, compared groups, dose and duration of isotretinoin, and depression assessment tool. The quality of included studies was assessed using the nine-star Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. This scale evaluated the study quality based on three parameters: selection, comparability, and exposure (case–control study) or outcome (cohort study). A maximum of four points was assigned for the item of selection, two points for comparability and three points for exposure/outcome.16 Studies were deemed as high quality for a score of 8–9, moderate quality for a score of 6–7 and low quality for a score ≤5.

Statistical analysis

The continuous outcome of interest was the alteration in depressive symptoms assessed using a continuous depression scale after the use of isotretinoin. For the continuous parameter of depression score, the means and SDs of the scores were extracted. The standardised mean difference (SMD) was used as the outcome measure. SMD was a unitless effect size estimate, which was the mean difference in the depression score between the compared groups divided by the pooled SD of the distribution of the score used in the study. The conversion of median (range/IQR) to mean±SD was done by a previously proposed method.17 The binary outcome of interest was the number of participants whose conditions were regarded as depression. RR and its corresponding 95% CI were used as the outcome measure. HR was regarded as equivalent to RR in cohort studies. Given the overall low incidence of depression among the general population, OR was assumed to be an accurate estimate of RR. It was preferred to use the effect measures that reflected the greatest degree control for confounding factors. Both adjusted and crude data were analysed. When data on different subgroups were reported by the same cohort, they were first pooled using the fixed-effects model. As the random-effects model was more robust than the fixed-effects model, the DerSimonian–Laird random-effects model was used to calculate the overall effect estimates for the association between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression.18 The heterogeneity was evaluated using the Cochrane Q test and the I 2 statistic. Heterogeneity was considered low, moderate or high for I 2 <25%, 25%–50% and >50%, respectively.19 20 Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the following confounders: region, study design, sample size, female percentage and depression scale. Furthermore, meta-regression analyses were performed for the continuous confounders of sample size and female percentage. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding a single study at a time. Also, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the weighted mean difference (WMD) as the effect estimate for studies employing the same depression symptom scale. The publication bias was visually assessed by constructing a funnel plot and statistically assessed using the Begg’s and Egger’s regression asymmetry tests.21 22 All statistical analyses were conducted using the software Stata V.12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and the public were not involved.

Results

Study selection

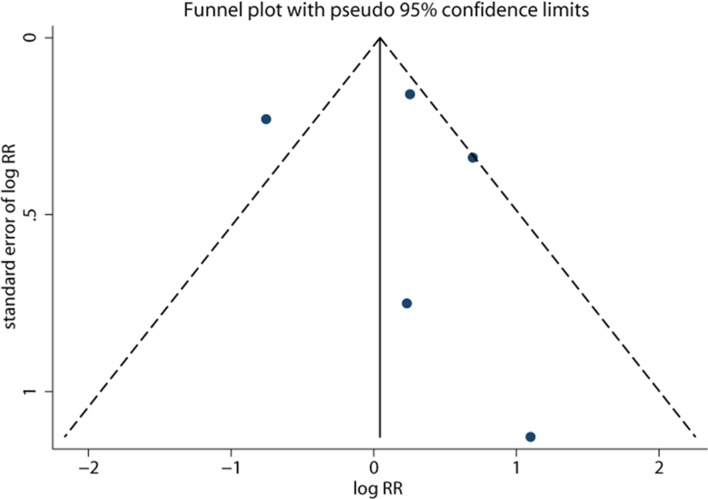

A total of 632 records was retrieved from the electronic search, including 145 studies from PubMed, 469 records from Embase and 18 records from the Cochrane library. After screening by titles and abstracts, 571 studies were excluded for the following reasons: reviews, editorials, case reports or irrelevant studies, leaving 61 studies for full-text review. Nine cross-sectional studies, 19 studies without sufficient data, and 13 reviews, editorials or comments were excluded. Finally, 20 studies were pooled into the meta-analysis.23–43 A flow diagram of the study selection process is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included 20 studies are shown in table 1. Jick et al reported two independent cohorts,24 which were analysed separately. Except for two retrospective studies identifying patients with depression using the International Classification of Diseases code,24 31 other studies were prospectively designed, and depression was assessed using depression symptom scales. The number of participants using isotretinoin ranged from 16 to 7195. The enrolled patients with acne were distributed around the world, including 14 cohorts from Europe, 3 from North America, 3 from Asia and 1 from Africa. The percentage of female patients ranged from 0% to 73%. Most studies compared data before and after the use of isotretinoin, except for two studies. Simic et al compared isotretinoin with vitamin C.35 Azoulay et al compared isotretinoin users with non-users.31 Most studies prescribed isotretinoin for moderate-to-severe acne. The dose of isotretinoin ranged largely from 0.5 mg/(kg⋅d) to 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d). The duration of the use of isotretinoin ranged from around 1 month to about half a year. The quality of included studies is shown in online supplementary 2. Most studies had satisfactorily high quality. The least satisfactory item was the adjustment of the confounding factors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author (year) | Region | Design | Isotretinoin users | Mean/median age (year) | Female (%) | Acne severity | Comparison groups | Dose | Treatment duration | Depression assessment |

| Kellett et al (1999)23 | UK | Prospective | 34 | 24 | 44 | NA | Before versus after | 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 4 months | HADS-D |

| Jick et al 24 (2000) a | Canada | Retrospective | 7195 | <30 (75%) | 47 | NA | Before versus after | 40 mg (86%) | 3–6 months (62%) | ICD code |

| Jick et al 24 (2000) b | UK | Retrospective | 340 | <30 (78%) | 42 | NA | Before versus after | 20 mg (75%) | 1–2 months (81%) | ICD code |

| Ng et al 25 (2002) | Australia | Prospective | 174 | 20 | 41 | Moderate to severe | Before versus after | 0.8–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 6 months | BDI |

| Ferahbas et al 26 (2004) | Turkey | Prospective | 23 | 20 | 43 | Severe | Before versus after | 0.5–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 4 months | MADRS |

| Kellett et al 28 (2005) | UK | Prospective | 33 | 25 | 36 | NA | Before versus after | 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 4 months | BDI |

| Kaymak et al 29 (2006) | Turkey | Prospective | 24 | 100 | 58 | Moderate | Before versus after | 0.75–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 5–7 months | HRS |

| Chia et al 27 (2005) | USA | Prospective | 59 | 12–19 | 25 | Moderate to severe | Before versus after | 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 3–4 months | CES-D |

| Azoulay et al 31 (2008) | Canada | Retrospective | 126 | 28 | 53 | NA | Users versus non-users | NA | 5 months | ICD code |

| Kaymak et al 33 (2009) | Turkey | Prospective | 37 | 21 | 69 | Mild to severe | Before versus after | 0.5–0.8 mg/(kg⋅d) | >5 months | BDI, HADS-D |

| Bozdag et al 32 (2009) | Turkey | Prospective | 50 | 20 | 52 | Moderate to severe | Before versus after | 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 4 months | BDI |

| Rehn et al 34 (2009) | Finland | Prospective | 126 | 20 | 0 | Moderate to severe | Before versus after | 0.5 mg/(kg⋅d) | 3 months | BDI |

| Simic et al 35 (2009) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Prospective | 85 | 19 | 34 | Moderate to severe | Isotretinoin versus vitamin C | 1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 2 months | BDI |

| McGrath et al 36 (2010) | UK | Prospective | 65 | 20 | 31 | Mean AGS score 3.3 | Before versus after | 0.5–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 3 months | CES-D |

| Ergun et al 38 (2012) | Turkey | Prospective | 65 | 22 | 73 | Severe or resistant | Before versus after | 0.5–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | ≈ 5 months | HADS-D |

| Ormerod et al 39 (2012) | UK | Prospective | 16 | 22 | 25 | Severe | Before versus after | 0.5–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 3–6 months | BDI |

| Yesilova et al 40 (2012) | Turkey | Prospective | 43 | 23 | 70 | Mild to severe | Before versus after | 0.5–1.0 mg/(kg⋅d) | 6 months | HADS-D |

| Marron et al 41 (2013) | Spain | Prospective | 346 | 21 | 59 | Moderate | Before versus after | Total: 120 mg/kg | 7 months | HADS-D |

| Fakour et al 37 (2014) | Iran | Prospective | 98 | 22 | 61 | Severe | Before versus after | 0.5 mg/(kg⋅d) | 4 months | BDI |

| Gnanaraj et al 42 (2015) | India | Prospective | 143 | 21 | 34 | Moderate to severe | Before versus after | 0.5 mg/(kg⋅d) | 3 months | HRS |

| Suarez et al 43 (2016) | Venezuela | Prospective | 36 | 21 | 44 | Severe (25%) | Before versus after | 30 mg/d | 3 months | ZDS |

AGS, Acne Grading scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression; HRS, Hamilton Rating Scale; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; NA, not available; ZDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

bmjopen-2018-021549supp002.pdf (148.1KB, pdf)

Change in depression symptom scores after treatment

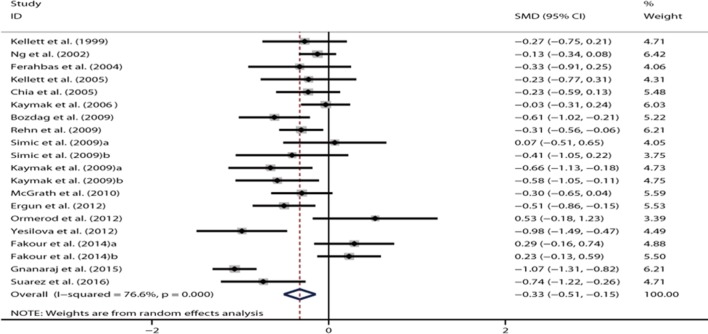

Seventeen studies reported the depression symptom scores before and after the use of isotretinoin. All studies were prospectively designed. Simic et al (2009) presented data for moderate and severe acne.35 Fakour et al showed data for males and females separately.37 Kaymak et al reported depression scores measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Scale and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression (HADS-D) Scale.33 These subgroup data were all pooled into the overall analysis. Compared with the baseline condition before therapy, the use of isotretinoin was associated with a significant improvement in depressive symptoms (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI −0.51 to −0.15, p<0.05) (figure 2). Highly significant heterogeneity was revealed (I 2=76.6%, p<0.05).

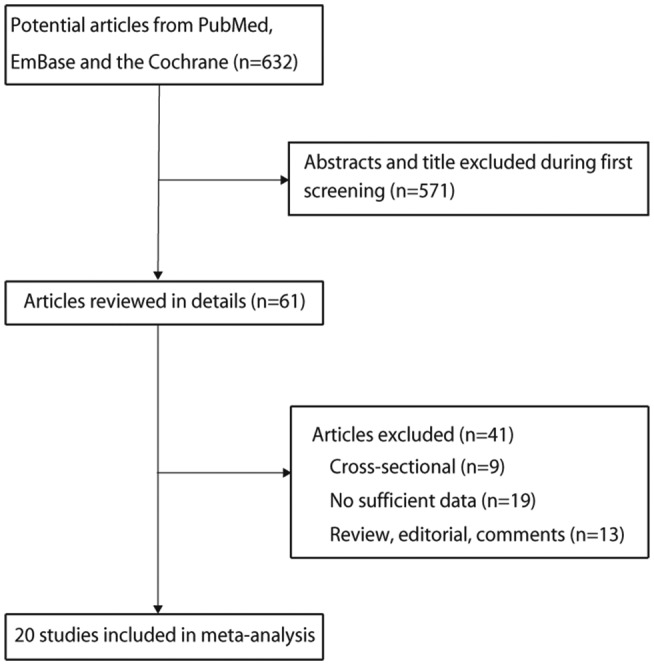

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the standardised mean difference for the comparison of depression symptom scores before and after isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne.

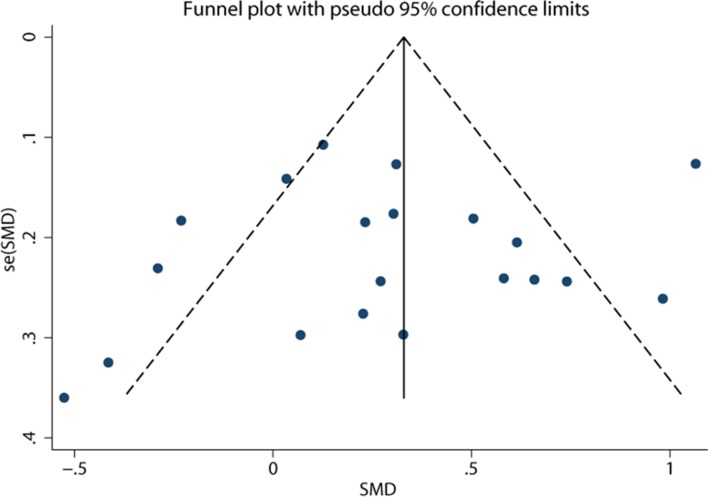

In the sensitivity analysis, the overall effect was not substantially altered when excluding any single study. In the meta-regression analysis, the number of included participants (p=0.995) and the female proportion (p=0.56) did not account for the source of heterogeneity. Data on subgroup analyses are shown in table 2. The pooled effect estimate remained significant for 14 European studies (SMD = −0.35, 95% CI −0.51 to −0.19, p<0.05) with moderate heterogeneity (I 2=46.3%). However, the analysis of three Asian studies did not show significant results (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI−0.81 to 0.45, p=0.57; I 2=94.4%). The use of isotretinoin had no significant effect on depressive symptoms in North America (SMD = –0.23, 95% CI –0.59 to 0.13; p=0.21), while it was associated with improved depressive symptoms in Africa (SMD = –0.74, 95% CI –1.22 to –0.26, p<0.05). The pooled results remained significant for studies using HADS-D (SMD = −0.57, 95% CI −0.83 to −0.31, p<0.25; I 2=27.2%) and those using the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI −0.52 to −0.02, p<0.05; I 2=0%). However, the pooled effect turned to be insignificant for studies using the BDI Scale (SMD = −0.15, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.06, p=0.17; I 2=62.4%) and those using the Hamilton Rating Scale (HRS) (SMD = −0.55, 95% CI −1.56 to 0.46, p=0.29; I 2=96.6%). The pooled effects were significant for both studies with a smaller sample size (SMD = −0.38, 95% CI −0.65 to −0.12, p<0.05) and those with a larger sample size (SMD = −0.29, 95% CI −0.54 to −0.04, p<0.05). The results for different proportions of females did not show a significant difference. The funnel plot appeared to be symmetrical (figure 3). No publication bias was revealed using the Egger’s test (p=0.76) or the Begg’s test (p=0.87).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis for studies presenting depressive symptom scores after isotretinoin compared with the baseline

| Subgroups | Number of cohorts | SMD (95% CI) | P value | I 2 (P value) |

| Region | ||||

| Europe | 14 | −0.35 (−0.51 to −0.19) | <0.05 | 46.3% (<0.05) |

| Asia | 3 | −0.18 (−0.81 to 0.45) | 0.57 | 94.4% (<0.05) |

| North America | 1 | −0.23 (−0.59 to 0.13) | 0.21 | − |

| Africa | 1 | −0.74 (−1.22 to −0.26) | <0.05 | − |

| Depression scale | ||||

| BDI | 10 | 0.10 (−0.12 to 0.32) | 0.38 | 65.2% (<0.05) |

| HADS-D | 4 | 0.57 (0.31 to 0.83) | <0.05 | 27.2% (0.25) |

| CES-D | 2 | 0.27 (0.02 to 0.52) | <0.05 | 0% (0.78) |

| HRS | 2 | 0.55 (−0.46 to 1.56) | 0.29 | 96.6% (<0.05) |

| MADRS | 1 | 0.33 (−0.25 to 0.91) | 0.27 | − |

| ZDS | 1 | 0.74 (0.26 to 1.22) | <0.05 | − |

| Sample size | ||||

| <50 | 9 | −0.38 (−0.65 to −0.12) | <0.05 | 64.0% (<0.05) |

| ≥50 | 11 | −0.29 (−0.54 to −0.04) | <0.05 | 83.1% (<0.05) |

| Percentage of female patients | ||||

| <50 | 12 | −0.32 (−0.55 to −0.09) | <0.05 | 76.8% (<0.05) |

| ≥50 | 8 | −0.34 (−0.04 to −0.64) | <0.05 | 78.4% (<0.05) |

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression; HRS, Hamilton Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; SMD, standardised mean difference; ZDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of studies comparing depression symptom scores before and after isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne. SMD, standardised mean difference.

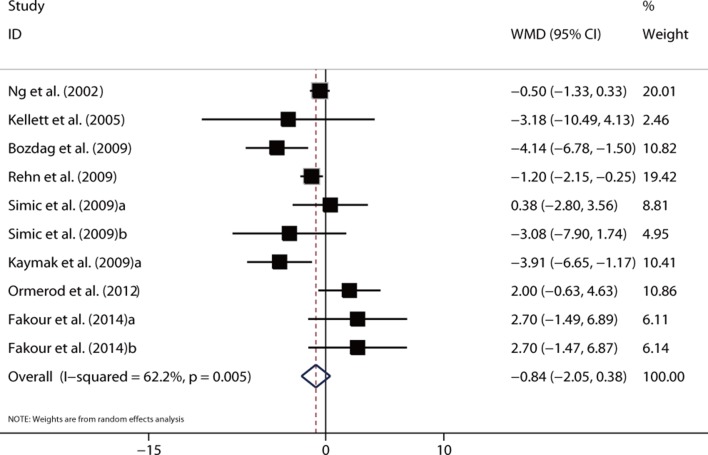

Also, the sensitivity analysis was performed by pooling the WMD for studies using the same scale. The pooled results were insignificant for studies using the BDI Scale (WMD = −0.84, 95% CI −2.05 to 0.38, p=0.18; I 2=62.2%, p<0.05) (figure 4) and those using the HRS (WMD = −1.91, 95% CI −5.44 to 1.63, p=0.29; I 2=97.3%, p<0.05). In contrast, the pooled WMDs were significant for studies using HADS-D (WMD = −2.06, 95% CI −3.42 to −0.70, p<0.05; I 2=66.0%, p<0.05) and those using CES-D (WMD = −1.88, 95% CI −3.64 to −0.11, p<0.05; I 2=0%, p=0.63).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the weighted mean difference (WMD) for the comparison of BDI scores before and after isotretinoin treatment in patients with acne.

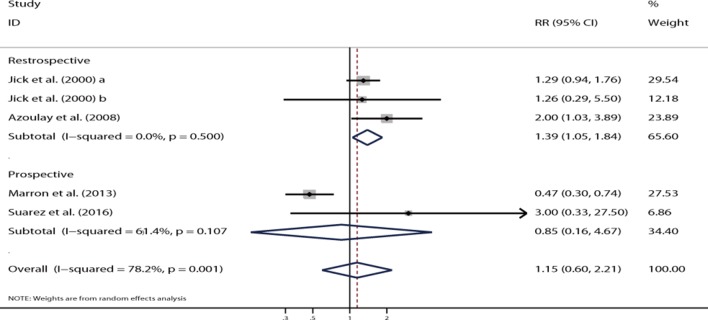

Use of isotretinoin and risk of depression

Two retrospective studies showed the adjusted RR for the association between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression.24 31 Jick et al presented data for two independent cohorts. The overall result of three cohorts showed that the use of isotretinoin was associated with an increased risk of depression (RR=1.39, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.84, p=0.02; figure 5), and no significant heterogeneity was shown (I 2=0.0%, p=0.50). However, no significant difference was noted in the relationship between isotretinoin use and the risk of depression on pooling two prospective studies (RR=0.85, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.21, p=0.86; figure 5), and a substantial heterogeneity was observed (I 2=61.4%, p=0.11). The funnel plot appeared to be symmetrical (figure 6), and Egger’s test (p=0.76) or Begg’s test (p=1.00) suggested no evidence of potential publication bias.

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing the association between isotretinoin treatment and depression in patients with acne.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot showing the association between isotretinoin treatment and depression in patients with acne.

Discussion

The risk of depression associated with the use of isotretinoin in patients with acne has been a major concern for a long time. Previous data showed conflicting and inconsistent results. This meta-analysis assessed the association between the use of isotretinoin and the risk of depression. It had several strengths as follows. A comprehensive database search of worldwide cohorts was conducted, enrolling a large number of participants. The quality of included studies was largely moderate to high. Most included studies were prospectively designed. The association was investigated from several aspects. The heterogeneity was explored by sensitivity, subgroup and meta-regression analyses. The present findings showed that isotretinoin improved in depressive symptoms in patients with acne. The benefit remained marked for studies using HADS-D and CES-D. In risk assessment, the summary RR showed that the use of isotretinoin was associated with an increased risk of depression in patients with acne on pooling retrospective studies, while this significant difference was not observed on pooling prospective studies.

Two previous systematic reviews on this topic were identified.13 44 They showed conflicting results, and hence the association between isotretinoin use and depression remained controversial. Further, although comprehensive scenarios were presented, data synthesis to obtain pooled results could not be conducted. Vallerand conducted a systematic review based on 11 trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral isotretinoin for acne. Oral isotretinoin significantly reduced the counts of acne lesions but increased the frequency of psychiatric adverse events (depressed mood, fatigue, hallucination, insomnia and lethargy; 32 vs 19). However, this study did not provide the result by data synthesis.45 Further, Huang et al conducted a meta-analysis based on 31 studies and suggested that the use of isotretinoin did not affect the incidence of depression. Further, they showed that the treatment of acne could ameliorate depressive symptoms. However, the study summarised the investigated outcomes using the depression assessment tool. Whether these relationships differed according to the region, study design, sample size and the female percentage, was not illustrated.46 Therefore, the present study was conducted to evaluate any potential impact of the use of isotretinoin on depression incidence and change in the depression score.

The concern for negative mood arose from a series of experimental studies. Oral isotretinoin significantly suppressed cell division in the hippocampus and severely disrupted the learning capacity of mice.47 Bremner et al found that the use of isotretinoin, but not antibiotics, was associated with decreased brain metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex, which was known to mediate depression symptoms.48 O’Reilly et al proved that isotretinoin altered intracellular serotonin level and increased 5-HT1A receptor and serotonin reuptake transporter levels in vitro.49 Thus, theoretically, isotretinoin itself might cause depressive disorders. However, the potentially increased risk of depression could be compensated by the beneficial effects of isotretinoin on patients with acne. Most patients with acne were worried about their appearances, which might lead to a series of psychological disorders. It was inferred that the improvement in depression symptoms after the use of isotretinoin might be attributed to the treatment success. Also, isotretinoin had a gradual effect on mood over time, which was not an acute event.50

Of note, the controversy over this topic was complicated by various confounding psychosocial and clinical factors. Aktan et al suggested that adolescent girls were more vulnerable to the negative psychological effects of acne compared with boys.51 Women with acne were significantly more embarrassed about their skin disease compared with males. A large database study showed that female gender and acne could jointly increase the risk of depression.52 However, the role of gender was not revealed in meta-regression and subgroup analyses. Acne itself can exert different impacts on individual patients. The lack of knowledge, especially about prognosis, may be a source of depression.24 53 Approximately a fifth of patients with acne suffered from psychiatric disorders.33 Better health education and care are important components for treating patients with acne. They help eliminate the patients’ misconceptions about the disease and unrealistic treatment expectations.54 The psychological interventions may vary between different clinical settings and lead to a bias in the effect of isotretinoin. Besides, data on the efficacy or side effect of the use of isotretinoin were insufficient in most included studies. Isotretinoin may cause teratogenic toxicity. Contraceptives are recommended for female users of fertile age to prevent pregnancy until the completion of the treatment.41 The levels of blood cholesterol and liver enzymes may be abnormal and should be monitored during the treatment phase.55

This meta-analysis had several shortcomings. The sample sizes of some included studies were still small, which might have limited the statistical power and increased the chance of missing small effects. The current pooled analysis was based on observational studies and no RCT was available, which may overestimate the association between isotretinoin use and depression risk. Moreover, we included in the article the study designed as observational study might have a bias caused by participant selection and confounding factors. Ideally, RCTs comparing isotretinoin with placebo or other agents may provide more robust findings, whereas most included studies compared the before-treatment and after-treatment data. However, leaving patients with moderate-to-severe acne without the use of isotretinoin may be unfair and even not ethical. Additionally, the treatment duration, drug dose and depression scale varied between different studies. The acne severity or the dose of isotretinoin varied and was not reported by several studies. Patients with severe acne or scars or those unresponsive to therapy might have a worse depressive mood. However, the analyses for these confounding factors were insufficient in most studies. Approximately a fifth of patients with acne suffered from psychiatric disorders.33 Also, some studies were sponsored by corporations,24 which might have underestimated the incidence of depressive disorders. Finally, although a greater risk of depression was associated with the use of isotretinoin on pooling retrospective studies, selection and recall biases might have affected the incidence of depression. Further, these conclusions might be unreliable because smaller cohorts were included in such subsets.

This meta-analysis showed that patients might have improved depressive symptoms after the use of isotretinoin. Further, the use of isotretinoin in patients with acne did not contribute to the development of depression. However, the summary results of retrospective studies suggested that the use of isotretinoin in patients with acne might increase the risk of depression. Future prospective controlled trials are warranted to verify the present findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: CQL and LK contributed to conception and design. CQL, JMC, WW, MA, QZ and LK contributed to data acquisition or analysis and interpretation of data. CQL, JMC, WW, MA, QZ and LK were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.ft545hs.

References

- 1. Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet 2012;379:361–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katsambas AD, Stefanaki C, Cunliffe WJ. Guidelines for treating acne. Clin Dermatol 2004;22:439–44. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dreno B, Poli F. Epidemiology of acne. Dermatology 2003;206:7–10. 10.1159/000067817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. James WD. Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1463–72. 10.1056/NEJMcp033487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas DR. Psychosocial effects of acne. J Cutan Med Surg 2004;8(Suppl 4):3–5. 10.1007/s10227-004-0752-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saitta P, Keehan P, Yousif J, et al. . An update on the presence of psychiatric comorbidities in acne patients, Part 2: Depression, anxiety, and suicide. Cutis 2011;88:92–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dawson AL, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris. BMJ 2013;346:f2634 10.1136/bmj.f2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chivot M. Retinoid therapy for acne. A comparative review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:13–19. 10.2165/00128071-200506010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wessels F, Anderson AN, Kropman K. The cost-effectiveness of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne. Part 1. A meta-analysis of effectiveness literature. S Afr Med J 1999;89:780–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurek A, Johanne Peters EM, Sabat R, et al. . Depression is a frequent co-morbidity in patients with acne inversa. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2013;11:743–9. 43-50 10.1111/ddg.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borovaya A, Olisova O, Ruzicka T, et al. . Does isotretinoin therapy of acne cure or cause depression? Int J Dermatol 2013;52:1040–52. 10.1111/ijd.12169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolverton SE, Harper JC. Important controversies associated with isotretinoin therapy for acne. Am J Clin Dermatol 2013;14:71–6. 10.1007/s40257-013-0014-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kontaxakis VP, Skourides D, Ferentinos P, et al. . Isotretinoin and psychopathology: a review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2009;8:2 10.1186/1744-859X-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(Suppl 11):S454–66. 10.1002/acr.20556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. . The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://wwwohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp

- 17. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. . Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:135 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:273–82. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02662.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jick SS, Kremers HM, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C. Isotretinoin use and risk of depression, psychotic symptoms, suicide, and attempted suicide. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:1231–6. 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng CH, Tam MM, Celi E, et al. . Prospective study of depressive symptoms and quality of life in acne vulgaris patients treated with isotretinoin compared to antibiotic and topical therapy. Australas J Dermatol 2002;43:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferahbas A, Turan MT, Esel E, et al. . A pilot study evaluating anxiety and depressive scores in acne patients treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatolog Treat 2004;15:153–7. 10.1080/09546630410027472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chia CY, Lane W, Chibnall J, et al. . Isotretinoin therapy and mood changes in adolescents with moderate to severe acne: a cohort study. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:557–60. 10.1001/archderm.141.5.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ. A prospective study of the responsiveness of depression and suicidal ideation in acne patients to different phases of isotretinoin therapy. Eur J Dermatol 2005;15:484–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaymak Y, Kalay M, Ilter N, et al. . Incidence of depression related to isotretinoin treatment in 100 acne vulgaris patients. Psychol Rep 2006;99:897–906. 10.2466/PR0.99.3.897-906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen J, Adams S, Patten S. No association found between patients receiving isotretinoin for acne and the development of depression in a Canadian prospective cohort. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2007;14:e227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Azoulay L, Blais L, Koren G, et al. . Isotretinoin and the risk of depression in patients with acne vulgaris: a case-crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:526–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bozdağ KE, Gülseren S, Güven F, et al. . Evaluation of depressive symptoms in acne patients treated with isotretinoin. J Dermatolog Treat 2009;20:293–6. 10.1080/09546630903164909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaymak Y, Taner E, Taner Y. Comparison of depression, anxiety and life quality in acne vulgaris patients who were treated with either isotretinoin or topical agents. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:41–6. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rehn LM, Meririnne E, Höök-Nikanne J, et al. . Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation during isotretinoin treatment: a 12-week follow-up study of male Finnish military conscripts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:1294–7. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simić D, Situm M, Letica E, et al. . Psychological impact of isotretinoin treatment in patients with moderate and severe acne. Coll Antropol 2009;33(Suppl 2):15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGrath EJ, Lovell CR, Gillison F, et al. . A prospective trial of the effects of isotretinoin on quality of life and depressive symptoms. Br J Dermatol 2010;163:1323–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fakour Y, Noormohammadpour P, Ameri H, et al. . The effect of isotretinoin (roaccutane) therapy on depression and quality of life of patients with severe acne. Iran J Psychiatry 2014;9:237–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ergun T, Seckin D, Ozaydin N, et al. . Isotretinoin has no negative effect on attention, executive function and mood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:431–9. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ormerod AD, Thind CK, Rice SA, et al. . Influence of isotretinoin on hippocampal-based learning in human subjects. Psychopharmacology 2012;221:667–74. 10.1007/s00213-011-2611-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yesilova Y, Bez Y, Ari M, et al. . Effects of isotretinoin on obsessive compulsive symptoms, depression, and anxiety in patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat 2012;23:268–71. 10.3109/09546634.2011.608782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marron SE, Tomas-Aragones L, Boira S. Anxiety, depression, quality of life and patient satisfaction in acne patients treated with oral isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol 2013;93:701–6. 10.2340/00015555-1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gnanaraj P, Karthikeyan S, Narasimhan M, et al. . Decrease in "hamilton rating scale for depression" following isotretinoin therapy in acne: an open-label prospective study. Indian J Dermatol 2015;60:461–4. 10.4103/0019-5154.164358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Suarez B, Serrano A, Cova Y, et al. . Isotretinoin was not associated with depression or anxiety: a twelve-week study. World J Psychiatry 2016;6:136–42. 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marqueling AL, Zane LT. Depression and suicidal behavior in acne patients treated with isotretinoin: a systematic review. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2007;26:210–20. 10.1016/j.sder.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Farris MS, et al. . Efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:76–85. 10.1111/bjd.15668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang YC, Cheng YC. Isotretinoin treatment for acne and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:1068–76. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Crandall J, Sakai Y, Zhang J, et al. . 13-cis-retinoic acid suppresses hippocampal cell division and hippocampal-dependent learning in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:5111–6. 10.1073/pnas.0306336101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bremner JD, Fani N, Ashraf A, et al. . Functional brain imaging alterations in acne patients treated with isotretinoin. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:983–91. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O’Reilly KC, Trent S, Bailey SJ, et al. . 13-cis-Retinoic acid alters intracellular serotonin, increases 5-HT1A receptor, and serotonin reuptake transporter levels in vitro. Exp Biol Med 2007;232:1195–203. 10.3181/0703-RM-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Misery L. Consequences of psychological distress in adolescents with acne. J Invest Dermatol 2011;131:290–2. 10.1038/jid.2010.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B. Anxiety, depression, and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:354–7. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang YC, Tu HP, Hong CH, et al. . Female gender and acne disease are jointly and independently associated with the risk of major depression and suicide: a national population-based study. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/504279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smithard A, Glazebrook C, Williams HC. Acne prevalence, knowledge about acne and psychological morbidity in mid-adolescence: a community-based study. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:274–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Thiboutot D, Dréno B, Layton A. Acne counseling to improve adherence. Cutis 2008;81:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hansen TJ, Lucking S, Miller JJ, et al. . Standardized laboratory monitoring with use of isotretinoin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;75:323–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021549supp001.pdf (19.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-021549supp002.pdf (148.1KB, pdf)