Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to use a theoretical approach to understand the determinants of behaviour in patients not home self-administering intravenous antibiotics.

Setting

Outpatient care: included patients were attending an outpatient clinic for intravenous antibiotic administration in the northeast of Scotland.

Participants

Patients were included if they had received more than 7 days of intravenous antibiotics and were aged 16 years and over. Twenty potential participants were approached, and all agreed to be interviewed. 13 were male with a mean age of 54 years (SD +17.6).

Outcomes

Key behavioural determinants that influenced patients’ behaviours relating to self-administration of intravenous antibiotics.

Design

Qualitative, semistructured in-depth interviews were undertaken with a purposive sample of patients. An interview schedule, underpinned by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), was developed, reviewed for credibility and piloted. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed thematically using the TDF as the coding framework.

Results

The key behavioural determinants emerging as encouraging patients to self-administer intravenous antibiotics were the perceptions of being sufficiently knowledgeable, skilful and competent and that self-administration afforded the potential to work while administering treatment. The key determinants that impacted their decision not to self-administer were lack of knowledge of available options, a perception that hospital staff are better trained and anxieties of potential complications.

Conclusion

Though patients are appreciative of the skills and knowledge of hospital staff, there is also a willingness among patients to home self-administer antibiotics. However, the main barrier emerges to be a perceived lack of knowledge of ways of doing this at home. To overcome this, a number of interventions are suggested based on evidence-based behavioural change techniques.

Keywords: qualitative research, opat, behaviours

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A theoretical framework was used to underpin the research design and analysis.

It was apparent that data saturation was achieved.

The research was conducted within one only hospital in the northeast of Scotland; findings are not necessarily transferable to all outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics in the UK or beyond.

The study focused solely on patient perspectives, and no members of the healthcare team were interviewed.

Introduction

Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) is a treatment option in patients who require parenteral antibiotic administration and are clinically well enough not to require an overnight hospital stay.1 OPAT was first described in the USA in the early 1970s for treatment of infectious exacerbations of cystic fibrosis2 and is now an option for management of diverse infections and patient populations. A model of care involves administration of intravenous antibiotics within the home setting (by a trained patient, carer or health professional).2

The expansion of OPAT worldwide has been driven by factors including: a drive for more cost-effective use of resources; reduced risks of healthcare acquired infection; alignment with the philosophy of patient driven care; an aim to achieve high levels of patient acceptability and satisfaction; and improved quality of life. Evidence of these outcomes has been derived from a systematic review of the cost effectiveness of OPAT highlighting that OPAT is cost-effective without increasing patient complications.3 A narrative review of studies concluded that patients prefer home administration allowing continuation of daily activities.2 Other cohort studies showed no increased risk of developing healthcare acquired infections, particularly Clostridium difficile. 4–6 Further evidence concluded there are no additional risks of patient home self-administration of antibiotics compared with hospital administration.2 7–9

Several organisations have disseminated guidance and consensus practice statements for OPAT, promoting safe and effective care.2 10 The British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy launched a number of related initiatives including the National Outcomes Registry System (NORS).11 Audit data from NORS for 2015 are available for 10 OPAT centres in England. No OPAT centres in Scotland are registered with NORS.12

Within the northeast of Scotland, an OPAT clinic was established in a major teaching hospital in 1999 to deliver and coordinate OPAT administration to patients. This includes OPAT self-administration within the home setting or, for those who opt for health professional administration, treatment is given at the teaching hospital clinic or at a local healthcare setting. While other centres in Scotland are reporting increased uptake of home self-administration,5 uptake in this centre has decreased from 53% in 2006 to 15% in 2013 and 24% in 2015 (personal communication). There is a need to investigate the low uptake here with a potential to develop and implement a behaviour change intervention to increase home self-administration.

Such behaviour change interventions are likely to be deemed ‘complex’ since there are ‘several interacting components’. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on ‘Developing, Implementing and Evaluating Complex Interventions’ suggests a four stage process; the first is intervention development.13 Consideration of role of cognitive, behavioural and organisational theories in this phase is emphasised; this will generate an intervention with a ‘coherent theoretical basis’, which is more likely to be effective and bring about sustained change.13

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is a framework of theories of behaviour change. To overcome the challenge of selecting the most appropriate theory from the vast number available, TDF was developed, aiming to ‘… simplify and integrate a plethora of behaviour change theories and make theory more accessible to, and usable by, other disciplines’.14 It is organised into 14 overarching domains and has been used increasingly to explore behaviours in various clinical settings.15

This study aimed to use a theoretical approach to understand the determinants of behaviour in patients who are not home self-administering antibiotics.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative study comprising face-to-face semistructured interviews.

Setting

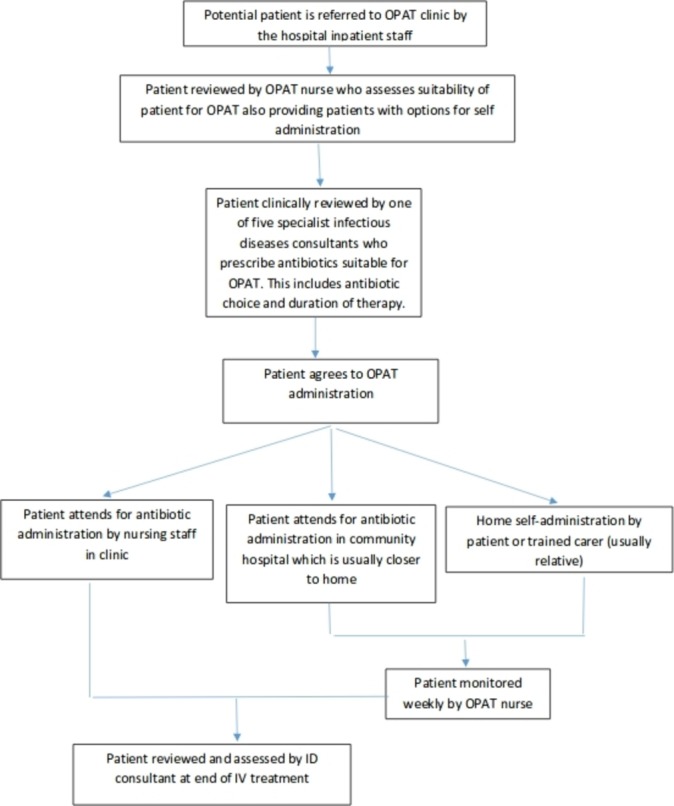

The study was conducted in an OPAT clinic in a 900 bedded hospital in the northeast of Scotland. Patient flow within this clinic is at figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of patient flow within OPAT clinic. OPAT, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Around 150 patients per year attend the clinic (table 1). Duration of antimicrobial therapy varies from a few days to 4–6 weeks depending on the condition.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients referred for OPAT in 2015 (personal communication)

| Number of patients | 147 |

| Number of OPAT episodes | 3790 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | 45 |

| Spinal abscess/discitis | 35 |

| Joint infection | 24 |

| Osteomyelitis | 19 |

| Bronchiectasis | 16 |

| Lyme disease | 7 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 |

| Administration | |

| Administered in clinic | 76 |

| Administered in community hospital | 36 |

| Administered by self | 35 |

| Duration of treatment (days) | |

| 0–7 | 39 |

| 8–14 | 26 |

| 15–21 | 15 |

| 22–28 | 17 |

| ≥28 | 50 |

OPAT, outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design of this research.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they were: found to be suitable for OPAT by clinic OPAT nurse and specialist infectious diseases consultants; requiring intravenous antibiotics for a period exceeding 7 days; and were not home self-administering intravenous antibiotics.

Patients were excluded if they: were 16 years or under; deemed by the OPAT nurse as having no capacity to provide informed consent; had limited understanding of English; or had special communication needs as deemed by clinic team.

The sampling was purposive, and all patients meeting the inclusion criteria who attended the clinic over the study period were included (February–July 2015). An initial sample size of 10 was aimed for with sampling then continued until a point of saturation was reached at which no new themes emerged from three consecutive interviews.16

Recruitment

The OPAT nurse discussed the study with patients face-to-face and provided patients who were interested and meeting the inclusion criteria with a study information pack. Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients who agreed to participate. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any point during the interview and up to 7 days after.

Development of interview schedule

The semistructured interview schedule was based on the 14 domains of TDF, with core questions and probes to allow an in-depth understanding of the determinants relating to their decision to not self-administer.14 The schedule was reviewed for credibility by members of the research team providing breadth of expertise in medicine, pharmacy, behavioural psychology and research.17

Core questions and links to TDF domains are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Interview schedule: the questions are underpinned by TDF, and all 14 domains were covered in the development of the interview schedule; some questions cover multiple domains14

| TDF domain | Relevant question/s |

| Knowledge: an awareness of the existence of something | Can you briefly describe to me why you are on antibiotics? Can you tell me the name of the antibiotic and for how long you have been prescribed this? Can you describe to me the different alternatives that may be used to inject the antibiotics? For example, coming to the clinic daily. |

| Skills: an ability or proficiency acquired through practice | Do you feel you have the necessary:

|

| Social/professional role and identity: a coherent set of behaviours and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting | Is injecting of antibiotics only a nurse or a doctors’ role? Why? Is there a role for others such as patients, relatives, carers to inject at home? Why? |

| Beliefs about capabilities: acceptance of the truth, reality or validity about an ability, talent or facility that a person can put to constructive use | Do you feel you have the necessary:

|

| Optimism: the confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained | Did you consider the impact on yourself and others (hospital staff, family and so on) when making the decision? |

| Beliefs about consequences: acceptance of the truth, reality or validity about outcomes of a behaviour in a given situation | Do you think you are likely to be cured better if your antibiotics are administered at hospital? Why? What do you think might have happened if you had chosen to inject at home? For example, consequences to yourself (including curing your infection), family and so on. Is there anything that could help you overcome the problems and difficulties you have mentioned? For example, relative, more time training and overseeing injecting. |

| Reinforcement: increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus | What might be done differently to encourage more people to inject at home? Based on all issues, what is the most important thing that healthcare professionals could have done to encourage you to inject at home? |

| Intentions: a conscious decision to perform a behaviour or a resolve to act in a certain way | Did you consider the impact on yourself and others (hospital staff, family and so on) when making the decision? |

| Goals: mental representations of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve | How does coming to hospital fit in with your daily routine? Are there situations where other things you have to do have interfered with coming to hospital? |

| Memory, attention and decision processes: the ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment and choose between two or more alternatives | Describe to me how you made the decision to come to hospital for your antibiotic treatment rather than injecting at home. Was it an easy decision to make? Do you feel you were in charge of making that decision and why? What situations may cause you to forget/decide not to inject the antibiotic if you were injecting at home (eg, time constraints, the presence of others, cleanliness, supplies, small children, risk of infection and so on)? |

| Environmental context and resources: any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence and adaptive behaviour | How does hospital administration help meet your personal needs (eg, interaction with other patients, support from clinic staff, reassurance that you are seeing medical staff regularly)? How would injecting at home fit in with your daily routine? |

| Social influences: those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours | Did others influence your decision to come to hospital? How? (prompts family, friends, work colleagues, other patients, hospital staff [name staff], others who have injected at home?) Did they think it was a good or a bad idea? Did they agree with your decision and why? Who had the final say in making the decision about injecting at home? |

| Emotion: a complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event | How do you feel about self-injecting at home? What are the main things you would like/dislike about self-injecting at home? Does injecting at home cause you to worry? What specific concerns does it raise? How do you feel about receiving your antibiotics in hospital? What are the main things you like/dislike about coming to hospital? Do you worry about coming to hospital? What specific concerns does it raise? |

| Behavioural regulation: anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions | What would encourage you to inject at home in the future if antibiotics were needed again (eg, more training/support, meeting other patients who have self-injected successfully, having a relative/carer self-inject)? |

TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Two pilot interviews were conducted to establish patient understanding of interview questions and duration; no changes were made.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted within the OPAT clinic by GA, a researcher with considerable experience and expertise in conducting interviews, and recorded digitally, with ongoing verbatim transcription of audio-recordings to allow for identification of data saturation. All transcripts were checked for accuracy by an independent member of the research team (AT).

Data analysis

Transcripts were analysed independently by two researchers (GA and AT) using the Framework Approach following the steps of: data familiarisation; identifying constructs; indexing; charting; mapping; and interpreting.18 TDF was used as the coding framework to allow elucidation of the behavioural determinants. The coding of the first two interviews was reviewed by a third member of the research team (KF-M). Any disagreements were resolved by discussing with a third member of the team (KF-M).

Results

Demographics

Twenty patients were approached; all agreed to be interviewed. Interviews were between 30 min and 45 min long. The mean age was 54 years (SD±17.6 years); 13 were male and most (n=19) were at least in their second or third week of intravenous antibiotic treatment. Just under half (n=9) were being treated for a bone and joint infection (table 3).

Table 3.

Demographics in patients included in study

| Gender | Age range* | Any comorbidities | Indication for intravenous antibiotic therapy | Week of treatment | |

| P1 | F | 51–60 | No | Spinal infection – bone and joint | Third week |

| P2 | M | 41–50 | No | Osteomyelitis in finger | End of first week |

| P3 | F | 31–40 | Type 1 diabetic | Discitis | Second week |

| P4 | M | 21–30 | No | Knee septic arthritis | Third week |

| P5 | F | 61–70 | No | Hip prosthetic joint infection | Third week |

| P6 | M | 61–70 | No | Cellulitis in leg | Second week |

| P7 | M | 71–80 | No | Osteomyelitis in toe | Third week |

| P8 | M | 61–70 | No | Knee infection following total replacement | Third week |

| P9 | M | 71–80 | No | Osteomyelitis in toe | Second week |

| P10 | F | 61–70 | No | Osteomyelitis in tibia | Second week |

| P11 | M | 71–80 | Type 1 diabetic | Cellulitis in leg | Second week |

| P12 | M | 41–50 | No | Cellulitis and bursitis in elbow | Second week |

| P13 | M | 61–70 | Liver cirrhosis (non-alcoholic) | Lung disease—Mycobacterium infection | Sixth week |

| P14 | F | 61–70 | No | Osteomyelitis in toe | Fifth week |

| P15 | M | 31–40 | No | Infective endocarditis | Second week |

| P16 | M | 61–70 | Type 2 diabetic | Infected cannula site – cellulitis | Second week |

| P17 | M | 41–50 | No | Discitis | Third week |

| P18 | M | 17–18 | No | Infective endocarditis | Third week |

| P19 | F | 41–50 | No | Cellulitis in leg | Second week |

| P20 | F | 51–60 | No | Cellulitis in leg | Third week |

*The participant age have been reported in age ranges to ensure patient is not identifiable.

F, female; M, male.

Key themes are described in relation to TDF domains.

Domain 1: knowledge

Lack of knowledge of options available for self-administration

For all patients, there appeared to be a lack of knowledge of options available, including the possibility to self-administer intravenous antibiotics at home.

… they could have asked me as I told them I was a nurse … they could teach me what I needed to know to do these at home. P20

In fact, when aware of this option, some patients indicated that they would have been keen to learn how to self-administer.

Please you must show me and I can learn. Please can you teach me as it will be better and (do) no(t) have come in here everyday and for the money as well … help me get back to work … P15

Domain 2: skills

Patient perceptions of own skills to self-administer

Some perceived themselves as having necessary skills to self-administer, gained in various ways including observation of staff at OPAT clinic, past or present experiences with self-administration of injections and past training. This made the patients more willing to self-administer antibiotics at home in the future should the option be available.

Well you see it [self-administration] should be fairly simple … just remove the cap here and flush it and connect it push it in here to this and let it drip in slowly and then the alarm goes off and press stop and take the tube that connects to the machine and flush again …. It’s easy, just like plumbing! P13

A few identified specific skills they required to gain to pursue home self-administration of antibiotics.

.… more practice and how to flush the cannula and make sure it is not blocked. P2

Domain 3: social/professional role and identity

Some patients believed that it was not appropriate for them to self-administer and that this was the role of healthcare professionals. This influenced their decision to attend hospital rather than self-administer.

… Folk are nae [not] trained like hospital staff … so I would say leave this for the experts. P11

Many expressed confidence in the OPAT nurse.

Even if they [family members] did I would not trust them. She [OPAT nurse] is very good and does it quick and I know it’s safe. P1

Domain 4: beliefs about capabilities

Belief/lack of in own abilities

Many patients perceived themselves as being competent.

… So I don’t think giving the right dosage; I don’t think this would be an issue at all. I could cope with that. P5

These patients felt confident in their own capabilities should they be given the opportunity to be shown, taught and practice prior to self-administering at home.

However, some were lacking in self-confidence and did not believe they were capable of self-administration, citing reasons including complex and difficult home circumstances and physical inability to self-administer.

… The trouble is … I have the jitters and my doctors know about that as well.… I don’t know why I have this I have this jittering in my legs and some jittering in my arms. P8

Domain 5: belief about consequences

Belief that it is safer to have antibiotics administered in hospital

Administration of antibiotics in hospital provided some patients with reassurance that a knowledgeable healthcare professional was administering their therapy and perceived this as being a safer option to self-administration. Others felt secure that hospital was a cleaner environment than home. This encouraged patients to choose hospital administration over self-administration.

I thought it would be a lot safer to do them here in the hospital … I think hospitals are cleaned every day with antibacterials and the nurses wear gloves and use the gel so in that respect hospitals are much more cleaner and a much safer environment. P18

Some patients cited potential negative consequences if they self-administered.

The thing that really worries me about doing it at home is getting an infection. P17

Others remarked that it was likely to make no difference in terms of consequences whether the antibiotic was self-administered at home or in hospital by a healthcare professional.

They [antibiotics] would work exactly the same as it’s the same stuff and given the same way. P13

Belief that self-administration could potentially improve quality of life

Some patients thought that self-administration would facilitate their return to work since it would no longer be necessary to attend hospital on a daily basis.

See like if I could do it myself like then it could work around better and it would help a lot with getting back to work.… . as they say no work no pay. P3

Home self-administration was also considered to potentially have a positive impact on patient quality of life, including social life and having less impact on the rest of the family.

Coming in to hospital is a pain sometimes as I get job interviews and have turned down some of these as I’m coming here and I often cancel friends’ invites so I can come to the hospital. P2

Spending less time travelling was an incentive for patients to self-administer.

Well I don’t know other than it would save the journey in you see I live away out in XXX so it would save a long trip here and back. P7

In some cases, driving into hospital was also impacting other family members negatively.

Oh yeah because you would not need to rely on other people to take you in here. Normally my dad, who is a taxi driver takes me but he is losing the chance of making a fare every time he comes in with me. P19

Domain 6: environment context and resources

Lack of parking availability in hospital premises

A lack of parking availability within the hospital grounds and the distance required to reach the clinic were also cited as encouraging self-administration.

I had to walk from the rotunda [side entrance of the hospital], up the passage way to the lifts and I was a bit shaky by the time I got to the lift. P16

Complex home circumstances

Issues relating to patients’ dependents were also factors that would encourage self-administration.

Aye tell me about … it’s a bit of nightmare [coming into hospital daily]. We also have a two year old so my partner she works as well. P3

Just as home circumstances were a potential facilitator to home self-administration, patients also cited dependents and other home circumstances as being the reason behind the decision to opt out of self-administration.

… You see it’s complicated; my husband, he has dementia and takes up all my time. P1

One patient was required to attend hospital to have investigations as well as antibiotic administration making it more convenient to opt for hospital administration.

I think it’s more convenient to get everything done at the same time antibiotics, blood tests … P13

Another patient discussed his self-employment allowed flexibility in his daily schedule, which discouraged him from self-administering.

It does not bother me [coming in] cause it’s my own business so I’m the boss … I can be totally flexible and can come in any time of the day. P12

Domain 7: emotions

Anxiety and stress associated with self-administration

A number of patients felt that self-administration would be a complex task that would be too stressful leading to considerable anxiety including a fear of using and handling needles.

I would consider it but I would never have the confidence to do it … if I had to use a needle I would not do it. I’m petrified of needles. P6

Concern about potential complications and consequences of self-administration also acted as a barrier to learning to self-administer antibiotics.

It’s not the learning so much it’s the doing and what to do if it goes wrong. What about if it (the antibiotic) goes in the wrong place? … I feel sick … P1

Importance of staff reassurances and encouragement

Some patients stressed the importance of hospital staff potentially exerting a positive effect calming patients’ stresses and anxieties by providing reassurance during the training process.

The most important thing though is to have the staff like you to do it [training] right and support and instil confidence in their patients. P20

Domain 8: memory, attention and decision process

Patient involvement in decision making

This domain involved the decision making and factors involved in patients choice between ways of administration. Many patients indicated that they were not involved and consulted in deciding whether to attend hospital or self-administer with decision to come to hospital made by hospital staff.

Well I didn’t get to make that choice. I was just told that I was going to get this treatment and that I would need to come into hospital three times a week to get these infusions and that was it. P18

Despite lack of involvement in the decision-making process, most expressed confidence in the healthcare professionals’ abilities and judgements.

I would say the doctor did whatever was best for my situation. P4

Domain 9: social influences

A number of patients indicated that hospital healthcare professionals suggested that it would be the better option for them if they attended hospital for administration of antibiotics. They did not question this suggestion in the belief that the healthcare professionals were right.

… I’m an 80 year old so I just do whatever they [doctors] say. P11

A patient indicated that his wife was the main influence encouraging him to attend the hospital for administration,

My wife … she prefers me to come in here as she always worries about me. P13

Another patient preferred the social aspect of attending a site outwith his home for administration.

No I’m happy to come in here, it gets me out gets me walking a little bit further. P4

A patient described attending hospital as more rewarding from a social aspect and this encouraged him to choose hospital administration as opposed to developing the skills to self-administer.

Well its fine it’s a trip in and I meet some nice people and I’m coming anyway for my radiotherapy.… I come in the patient transport. P7

Domain 10: behavioural regulation

Experiences gained through attending OPAT clinic

All patients had been attending the OPAT clinic for antibiotic administration for a number of days. Some indicated that following experiences of attending on a daily basis, they would still opt to attend the clinic given the choice in the future.

If you have got someone in my situation it may not be feasible for them to do it at home. P14

Others indicated that based on this experience, they would consider learning and training self-administration of antibiotics choosing this option in the future.

… they could teach me what I needed to know to do these at home and this would have reduced my stress levels I mean stress with childcare for my autistic son… P20

Information about these domains did not emerge from the available dataset: optimism, reinforcement, intentions and goals.

Barriers and facilitators to home self-administration emerging from this research have been summarised in table 4.

Table 4.

Barriers and facilitators to home self-administration

| TDF domain | Subtheme/s | Facilitators | Barriers |

| Knowledge | Lack of knowledge of potential options available for self-administration | √ | |

| Beliefs of capabilities | Belief and confidence in own abilities | √ | |

| Lack of confidence in own abilities | √ | ||

| Skills | A perception that have necessary skills to self-administer | √ | |

| Social/professional role and identity | Belief that not role of patient to self-administer | √ | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Belief that safer to administer in hospital | √ | |

| Belief that self-administration could potentially improve quality of life | √ | ||

| Environmental context/resources | Lack of parking on hospital grounds | √ | |

| Complex home circumstances | √ (dependents) |

√ (dependents) |

|

| Emotions | Anxiety and stress associated with self-administration | √ | |

| Staff reassurances, encouragement, support and training | √ | ||

| Social influences | Influences of family/friends | √ | |

| Memory, attention and decision process | Lack of patient involvement in decision making | √ | |

| Behavioural regulation | Experiences gained through attending OPAT clinic | √ | √ |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study adopting a qualitative methodology to explore the understanding, beliefs and attitudes of patients who are not self-administering intravenous antibiotics. Key findings are that from the patients’ perspectives, the main determinants that appeared to impact their decision not to self-administer were lack of knowledge of available options, a perception that hospital staff are better trained, and anxieties of potential complications of self-administration. The main determinants that emerged as potentially encouraging patients to self-administer included the perceptions of being sufficiently knowledgeable, skilful and competent, and that self-administration afforded the potential to work while receiving treatment. Patient experiences and awareness of options of OPAT administration were likely to impact future choices of self-administration. The novelty of the approach used in this research makes it difficult to compare with conclusions from other research, whether from the UK or outwith. To this effect, the discussion will focus on suggesting a number of interventions to overcome the barriers identified through this research and which are based on evidence-based behavioural change techniques. Overall, the interventions are aimed at promoting improvement in OPAT service delivery.

There are several strengths including use of a theoretical framework to underpin research design and analysis, and the measures taken to promote research trustworthiness, particularly the elements of credibility and dependability, enhancing research rigour.13 14 19 Furthermore, data saturation was apparent. There are, however, limitations to the study. The research was conducted within one hospital in the northeast of Scotland; findings are not necessarily transferable to all OPAT clinics in the UK or beyond. While there were attempts to promote credibility of findings such as having an interviewer who was not a member of the healthcare team, it is possible that some patients may not have been truthful. The study also focused solely on patient perspectives, and no members of the healthcare team were interviewed. Patients were interviewed if they were deemed suitable for self-administration by the team rather than based on whether they were provided the option of self-administration. Despite these limitations, this qualitative research has added to the very limited evidence base around behavioural determinants influencing a patient’s decision to self-administer intravenous antibiotics.

This study has elucidated the behavioural determinants acting as facilitators or barriers to self-administration that can act as targets for any intervention, promoting self-administration. The interventions suggested here will focus on the barriers rather than facilitators since these are the interventions most likely to increase uptake of self-administration. Patient-centred, tailored interventions may incorporate one or more behaviour change techniques (BCTs), described as processes that are likely to change behaviour. Michie et al mapped a number of evidence-based BCTs to specific TDF domains, highlighting the importance of considering theory as part of intervention development as articulated in the UK MRC guidance.13 20

Lack of belief in capabilities was a barrier to self-administration and resulted in lack of confidence in patient’s own abilities to self-administer. The mapped BCT ‘graded tasks’ may be implemented, where patients are initially set easy-to-perform tasks, followed by more complex tasks, aiming at building up the difficulty until the patient achieves the target behaviour. This approach may also alleviate the TDF emotional barriers relating to anxiety, providing reassurance over potential negative consequences of self-administration and the belief that hospital administration is safer.

While observing patients, the BCT of ‘verbal persuasion about capability’, could be considered whereby reassurance is provided of success, overcoming self-doubt and increasing self-belief. There is evidence that self-administration will also empower patients, increase autonomy leading to enhanced satisfaction.8

Stress was also a major negative emotion acting as a barrier to self-administration. In addition to skills-based training, BCTs should centre on emotional well-being in the form of ‘monitoring of emotional consequences’. Patients are encouraged to self-monitor their feelings while attempting self-administration. ‘Emotional social support’ could also be provided via a named healthcare professional, website or smartphone technology, which has had success in patients receiving home dialysis.21

There is a drive within healthcare services to involve patients in decision making taking on a person-centred approach. However, in this group of patients, though patients were praising of hospital staff, there appears to be a lack of involvement of patients in the decision-making process. Involvement of patients in decision making and the need for individualised discussions with patients on what is the better option for them should be encouraged and maybe an intervention targeted at healthcare professionals rather than patients.

While the interventions based on BCTs being suggested are taking into account most barriers to self-administration emerging in this research, in a few cases, it may be in the patient’s interest to attend the OPAT clinic, for example, patients with complex home circumstances.

A large number of patients in this research showed a lack of knowledge of self-administration as a potential option for administering intravenous antimicrobials. This is despite the fact that it is routine practice to provide home self-administration as an option to suitable patients. Aspects such as recall bias and social desirability bias linked to the patients’ responses need to be considered. Keeping in mind that this is from a patient perspective, a number of factors associated with the system, mainly the lack of resource available, may be a major contributor to this. There is one nurse caring for approximately 150 patients annually; however, current experience indicates that one nurse should care for 100 patients annually and having a larger ratio can have an impact on the ability of staff to assess patients for suitability of OPAT in a timely manner (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, personal communication 2016). The lack of resource makes it impossible for the nurse to provide the sufficient one-to-one training that is initially relatively intense but that has been described in the literature as providing success in allowing patients to safely self-administer at home.9 The investment in the resource may then be offset by the patient being discharged home and efficiently planned in a way that training is commenced when the patient is still a hospital inpatient. Additional resource such as equipment (eg, infusion pumps) that patients may be provided with at home also need to be considered to enable an increase in self-administration uptake rate.

Overall, this study shows that patients are very appreciative of the skills and expertise of healthcare professionals within the OPAT clinic. However, the study indicates that this expertise needs to shift so that skills and confidence are transferrable to patients through interventions based on BCTs. Though an initial investment in resource is required (including increased manpower and equipment), this will be offset in a number of ways particularly if training is commenced during the patient’s planned inpatient stay.9 More emphasis needs to be placed on informing the patients of the option of self-administration. To enhance the success of development of this complex intervention, further work is required to explore the views and perceptions of healthcare professionals to ensure that the development and implementation of any intervention is successful. Such research will also enable exploration of healthcare professionals being potential barriers or facilitators to self-administration. The hesitancy of healthcare professionals to initiate self-care has been shown as a major barrier in a small-scale US study as opposed to a patient reluctance to take on self-care.22

It is likely that in the near future, a more integrated approach towards patient care is adopted combining primary care expertise at home treatment and secondary care specialist knowledge.1 An OPAT service is an ideal way of embracing this.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the patients who took the time to be interviewed and without whose input this research would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. AT: principal investigator, involved in all aspects. GA: research fellow, involved in all aspects but mainly interviewing of patients, transcribing, data analysis and draft of work. IT, RL and AM: consultant infectious diseases physicians on site where study conducted. They lead mainly on conception of work and identifying the need for this research. VP and KF-M: involved mainly in design of work, particularly in development of theoretical basis for development of topic guide and analysis of data based on theoretical framework. SF: lead nurse at OPAT clinic and lead mainly on conception of work and recruitment of patients. GM: antimicrobial pharmacist and lead mainly on conception of work and analysis of data. DS: involved in all aspects overseeing the quality of the work and closely involved in conception and analysis and revising the final version for intellectual content.

Funding: This work was supported by an NHS Grampian Endowment Fund (Project number 14/14).

Disclaimer: The funding body had no involvement with study design.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Approval was obtained from the NHS Ethics Committee East Midlands–Nottingham 1 (14/EM/1197) and NHS Grampian Research and Development Office (2014RG007).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Due to confidentiality and need to protect the patient identity, there is no further data to share.

References

- 1. Chapman AL, Seaton RA, Cooper MA, et al. . Good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults in the UK: a consensus statement. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:1053–62. 10.1093/jac/dks003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacKenzie M, Rae N, Nathwani D. Outcomes from global adult outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy programmes: a review of the last decade. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014;43:7–16. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Psaltikidis EM, Silva E, Bustorff-Silva JM, et al. . Economic analysis of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (opat): a systematic review. Value Health 2015;18:A582–A583. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chapman AL. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. BMJ 2013;346:f1585 10.1136/bmj.f1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barr DA, Semple L, Seaton RA. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in a teaching hospital-based practice: a retrospective cohort study describing experience and evolution over 10 years. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012;39:407–13. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wong KK, Fraser TG, Shrestha NK, et al. . Low incidence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in patients treated with outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:110–2. 10.1017/ice.2014.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barr DA, Semple L, Seaton RA. Self-administration of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy and risk of catheter-related adverse events: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:2611–9. 10.1007/s10096-012-1604-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matthews PC, Conlon CP, Berendt AR, et al. . Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT): is it safe for selected patients to self-administer at home? A retrospective analysis of a large cohort over 13 years. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60:356–62. 10.1093/jac/dkm210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subedi S, Looke DF, McDougall DA, et al. . Supervised self-administration of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: a report from a large tertiary hospital in Australia. Int J Infect Dis 2015;30:161–5. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. . IDSA. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1651–71. 10.1086/420939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy initiative. http://www.bsac.org.uk/opat-landing-page/

- 12. British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. The national OPAT outcomes registry. http://opatregistry.com/index.php/auth/login

- 13. MRC, Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance

- 14. Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:37 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, et al. . Experiences of using the theoretical domains framework across diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8 10.2147/JMDH.S78458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. . What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory based studies. Psychology and Health 2009;10:1229–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis: HSR: Health Services Research; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1089059/pdf/hsresearch00022-0112.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ritchie J, Lewis J, McNuaghton Nicholls C, et al. . Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information 2004;22:63–75. 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, et al. . Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol Assess 2015;19:99–188. 10.3310/hta19990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Combes G, Allen K, Sein K, et al. . Taking hospital treatments home: a mixed methods case study looking at the barriers and success factors for home dialysis treatment and the influence of a target on uptake rates. Implement Sci 2015;10:148 10.1186/s13012-015-0344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agrawal D, Ganguly A, Bhavan PB. Capturing the patient voice. patients welcome iv self-care; physicians hesitate. http://catalyst.nejm.org/patients-welcome-iv-antibiotics-self-care/;2017 (Accessed 23 May 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.