Abstract

Context:

Family caregivers play critical and demanding roles in the care of persons with dementia through the end of life.

Objectives:

To determine whether caregiving strain increases for dementia caregivers as older adults approach the end of life, and secondarily, whether this association differs for nondementia caregivers.

Methods:

Participants included a nationally representative sample of community-living older adults receiving help with self-care or indoor mobility and their primary caregivers (3,422 dyads). Older adults’ death within 12-months of survey was assessed from linked Medicare enrollment files. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between dementia and end-of-life status and a composite measure of caregiving strain (range: 0–9, using a cut point of 5 to define “high” strain) after comprehensively adjusting for other older adult and caregiver factors.

Results:

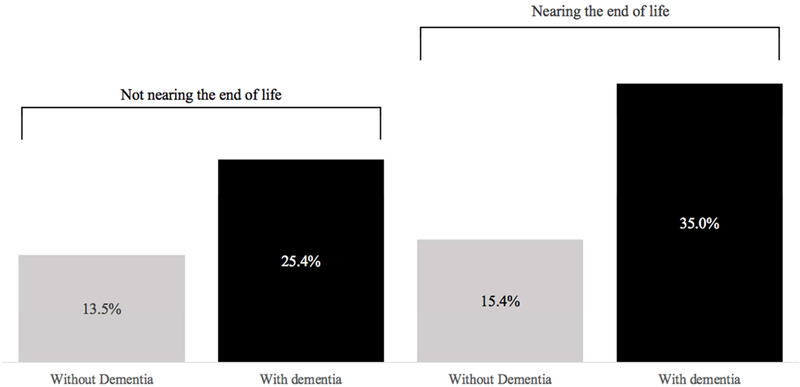

The prevalence of dementia in our sample was 30.1%; 13.2% of the sample died within 12-months. The proportion of caregivers who experienced high strain ranged from a low of 13.5% among non-dementia, non-end-of-life caregivers to a high of 35.0% among dementia caregivers of older adults who died within 12-months. Among dementia caregivers, the odds of high caregiving strain was nearly twice as high (aOR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.10–3.45) for those who were assisting older adults nearing end of life. Among non-dementia caregivers, providing care near the end of life was not associated with high strain.

Conclusion:

Increased strain toward the end of life is particularly notable for dementia caregivers. Interventions are needed to address the needs of this population.

Keywords: Family caregiving, strain, dementia, end-of-life care

INTRODUCTION

By 2050, eight to twelve million adults in the U.S. will be living with dementia (1), and dementia-related deaths are projected to exceed 40% of all deaths among older Americans (2). For persons with dementia, family members are often critical in hands-on care and decisionmaking over the course of disease and through the end of life: an estimated 70% of communitydwelling older adults with dementia receive assistance from a family member or other unpaid caregiver (3). Caring for someone with dementia poses unique difficulties (4–6), as deficits in memory and executive functioning may necessitate assistance with intimate self-care activities, and some older adults with dementia may be reluctant to accept help (4,7–11). When demands exceed capacity, caregiving imposes role-related strain (12,13). Strain may be more pronounced during advanced stages of dementia due to challenges of managing pain, dyspnea (14,15) and neuropsychiatric symptoms (16), inadequate access to palliative care (17–19) and burdensome interventions (14,20) that exact a toll on caregivers (21,22). In addition, decision-making regarding nursing home entry, hospitalizations, and use of life-sustaining and prolonging treatment (e.g., artificial nutrition) may contribute to increased strain among caregivers of all persons approaching end of life, regardless of dementia status.

Despite the plausibility of increased strain for end-of-life caregivers, relatively little is known about whether dementia caregivers experience increased strain as the care recipient approaches the end of life (15,23–28). Most prior research has been qualitative, restricted to persons living in institutionalized settings, or conducted outside of the US. Few studies have drawn on population-based, prospective data to compare caregiving experiences by survival status of the persons they assist (27). A recent national study found significantly greater strain among dementia caregivers of persons in the last year of life (29), but the analysis was descriptive and did not adjust for other contributors to caregiving strain. Therefore, we used nationally representative data and adjusted models in this analysis to determine whether caregiving strain increases for dementia caregivers as older adults approach the end of life, as we hypothesized it would. Secondarily, we sought to determine whether the end-of-life period is associated with increased strain for non-dementia caregivers.

METHODS

Data Sources:

We draw on data from two nationally representative surveys and their linked caregiver surveys: the National Long-Term Care Survey (NLTCS) and the Informal Care Survey (ICS) from 1999 and 2004, and the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and the National Survey of Caregiving (NSOC) from 2011 and 2015. Both surveys relied on the Medicare Enrollment Files as their sampling frame and both involved a complex sampling strategy with oversampling of specific subgroups. Additional details regarding the construction of the study sample and comparability of the NLTCS/ICS and NHATS/NSOC are elaborated in prior work (30).

Participants:

Our sample included community-living adults ages 65 years and older receiving assistance with self-care (eating, dressing, bathing, toileting) or indoor mobility (e.g. transferring) and the family or other unpaid caregiver who was identified as helping the most, i.e. their “primary” caregiver. The ICS was conducted with a “primary” caregiver defined as the caregiver providing the most hours of care (in 1999) or helping the most (in 2004). Because all caregivers in NHATS are eligible for NSOC, we followed a similar process in identifying the primary caregiver as the caregiver who provided the greatest number of hours of care, as described in earlier work (30). In total, our study sample comprised 3,422 older adult-caregiver dyads.

Exposures:

Older adult demographic and health characteristics included age, sex, race, education, Medicaid enrollment, self-reported health, number of activities of daily living for which they were receiving assistance, dementia, and end-of-life status. We used a composite measure of probable dementia based on self-reported diagnosis from a physician, knowledgeable informant’s reports of dementia-related symptoms and behaviors, and cognitive performance measures, as previously described (30,31). End of life refers to death within 12 months of survey from the Medicare Master Beneficiary File, as in prior literature (15,29,32,33). Measures of caregiver characteristics included age, sex, relationship to older adult, distance to older adult residence, self-reported health, employment status, use of respite services, and number of hours per week devoted to caregiving. Finally, we also adjusted for survey year in our models.

Outcome:

Our main outcome was derived from caregiver-reported measures. A composite measure of caregiving strain (range: 0–9) was constructed from six items (30,34). High caregiving strain was defined based on a cut-point of 5 or greater which corresponds to the 85th percentile of caregiving strain in our sample and has previously been found to have clinical relevance (34). The six items of the composite caregiver strain measure included caregiver appraisal of the difficulty of helping in three domains – emotional, physical, and financial – as well as having no time for oneself, being overwhelmed, and being exhausted. Caregivers were asked to report the level of emotional, physical, and financial difficulty related to helping. In the ICS, participants were asked to assess the difficulty of helping on a scale from 1 (“not difficult at all”) to 5 (“very difficult”). In the NSOC, participants were first asked “Is helping difficult?”; those responding “yes” were then asked to rate the difficulty of helping in each domain on a scale from 1 (“a little difficult”) to 5 (“very difficult”). In this study, difficulty helping was categorized as follows: 0 = no difficulty; 1 = some difficulty (ICS 2 or 3; NSOC 1, 2, or 3), and 2 = a lot of difficulty (ICS 4 or 5; NSOC 4 or 5). For questions about having no time for oneself, being overwhelmed, and being exhausted, affirmative responses were coded as 1, and negative responses as 0.

Statistical analysis:

We first described older adult and caregiver characteristics, stratified by the outcome of high caregiving strain. We then fit univariate logistic regression models to examine the associations of each older adult and caregiver characteristic with high caregiving strain. To identify independent factors associated with high caregiving strain, we then developed a full multivariable logistic regression model with conceptually relevant correlates of caregiving strain (13) in addition to survey year. Last, we constructed a model that included all measures from our full model, as well as an interaction term (the product of dementia status and end-of-life status) to assess if the relationship to caregiver-associated strain differed for caregivers of older adults by both dementia and end-of-life status.

Both the NLTCS and NHATS involve a complex, multistage sampling design with stratification, clustering, and oversampling of age and race subgroups, requiring sampling weights and survey design variables to produce nationally representative estimates and account for the complex survey design. This analysis used the NLTCS and NHATS weights and design variables as described in prior work (30). NLTCS and NHATS data is publicly available and deidentified. The JHSPH IRB reviewed the protocol for this study and deemed it to be exempt from human subjects board review. All analyses were conducted in Stata/IC 15.1.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Older Adults

The prevalence of dementia in our sample of community-living older adults receiving help with self-care or mobility was 30.1%. 13.2% of older adults in the sample died within 12months. Of those who died, the median time between interview and death was 170 days (interquartile range 85 to 262). The prevalence of high caregiving strain was greater among family caregivers assisting older adults who were male, with less than high school education, enrolled in Medicaid, and in worse health relative to those assisting older adults who were female, better educated, not-enrolled in Medicaid, and in better health (Table 1). Caregivers of older adults with dementia were approximately twice as likely to have high strain in comparison with those assisting older adults without dementia (27.2% vs. 13.7%; p<0.001). Caregivers of older adults who did not (versus did) survive 12 months were also more likely to have high strain (23.8% vs. 16.8%; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of community-living older adults receiving help with self-care and indoor mobility from a family/unpaid caregiver, stratified by caregiver strain

| Older Adult characteristic | Full sample (N=3422) |

Low or moderate strain (n=2702) |

High strain (n=720) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Column percentages |

Row percentages | |||

| Age [mean (95% CI)] | 78.7 (78.3, 79.0) | 78.5 (78.3, 78.7) | 79.2 (78.8, 79.6) | p=0.18 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 36.6% | 78.8% | 21.2% | p<0.001 |

| Female | 63.4% | 84.2% | 15.8% | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 78.7% | 82.0% | 18.0% | p=0.53 |

| Black or other | 21.3% | 83.2% | 16.8% | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than 12 years | 37.3% | 78.8% | 21.2% | p<0.001 |

| 12 or more years | 62.7% | 84.3% | 15.7% | |

| Medicaid recipient | ||||

| No | 77.9% | 83.0% | 17.0% | p<0.05 |

| Yes | 22.1% | 79.7% | 20.3% | |

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Excellent or good | 43.8% | 86.4% | 13.6% | p<0.001 |

| Fair or poor | 56.2% | 79.0% | 21.0% | |

|

Assistance with Activities of

Daily Living |

||||

| Standby, 1, or 2 ADLs | 65.4% | 87.8% | 12.2% | p<0.001 |

| 3 or 4 ADLs | 19.0% | 77.4% | 22.6% | |

| 5 or 6 ADLs | 15.6% | 64.7% | 35.3% | |

| Dementia Status | ||||

| Without dementia | 70.0% | 86.3% | 13.7% | p<0.001 |

| With dementia | 30.1% | 72.8% | 27.2% | |

| End-of-life status | ||||

| Survived 12 months | 86.8% | 83.2% | 16.8% | p<0.001 |

| Died within 12 months | 13.2% | 76.2% | 23.8% | |

Data drawn from National Long-Term Care Survey / Informal Care Survey data from 1999 (n= 791 dyads) and 2004 (n=1149 dyads), and National Health and Aging Trends Study / National Survey of Caregiving from 2011 (n= 736 dyads) and 2015 (n= 746 dyads). Data was weighted using NLTCS and NHATS weights as described in prior work (30). Statistical significance was assessed using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. High caregiving-associated strain was defined on the basis of a cut-point of 5 or greater on a scale of 0–9 based on six elements: emotional strain (0 = none; 1 = some; 2 = a lot), physical strain (0–2), financial strain (0–2), having no time for oneself (0 = false; 1 = true), being overwhelmed (0 or 1), and being exhausted (0 or 1). Dementia status identified through composite measures as specified in prior work (30,31). Older adults identified as nearing the end of life if they died within a year of survey completion as documented in the Medicare Master Beneficiary File. “Standby” assistance refers to data from the NLTCS only and is grouped with 1–2 self-care/ mobility activities so as to make the NLTCS and NHATS comparable, as previously described (30).

Characteristics of Family Caregivers

The proportion of caregivers who experienced high strain varied from a low of 13.5% among those caring for older adults without dementia not at the end of life to a high of 35.0% among caregivers of older adults with dementia who were approaching end of life (Figure 1). Caregivers who were female were more likely to experience high strain than those who were male (21.8% vs 10.5%; p<0.001), as were adult children relative to spouses or caregivers of “other” relationships (20.6% and 17.4% vs. 11.9%; p<0.001; Table 2). Caregivers who were themselves in fair or poor health were more than twice as likely to experience high strain than those in excellent, very good, or good health (29.2% vs. 13.7%; p<0.001). Those with high caregiving strain contributed an average of 49.9 hours per week, whereas those with low or moderate strain contributed an average of 28.8 hours (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Proportion of High Caregiving Strain among Family Caregivers, by Older Adult Dementia and End-of-Life Status

Table 2.

Characteristics of caregivers assisting community-living older adults receiving help with self-care and indoor mobility from a family/unpaid caregiver, stratified by caregiver-associated strain

| Caregiver characteristic | Full sample (N=3422) |

Low or moderate strain n=2702) |

High strain (n=720) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Column percentages |

Row percentages | |||

| Age [mean (95% CI)] | 62.8 (62.1, 63.5) | 63.0 (62.6, 63.4) | 61.9 (61.2, 62.6) | 0.11 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 35.8% | 89.5% | 10.5% | p<0.001 |

| Female | 64.2% | 78.2% | 21.8% | |

| Relationship to OA | ||||

| Spouse | 44.6% | 82.6% | 17.4% | p<0.001 |

| Child | 39.3% | 79.4% | 20.6% | |

| Other | 16.1% | 88.1% | 11.9% | |

| Distance to Older Adult | ||||

| Coreside | 75.9% | 81.4% | 18.6% | p=0.10 |

| Less than 10 minutes | 14.5% | 84.7% | 15.3% | |

| More than 10 minutes | 9.6% | 85.1% | 14.9% | |

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Excellent or good | 73.7% | 86.3% | 13.7% | p<0.001 |

| Fair or poor | 26.3% | 70.8% | 29.2% | |

| Employed for pay | ||||

| No | 71.1% | 83.0% | 17.0% | p=0.17 |

| Yes | 28.9% | 80.5% | 19.5% | |

| Respite use | ||||

| No | 86.3% | 83.7% | 16.3% | p<0.001 |

| Yes | 13.7% | 73.1% | 26.9% | |

| Hours per week of care provided [mean (95% CI)] |

32.6 (30.8, 34.4) | 28.8 (27.8, 29.8) | 49.9 (47.8, 52.0) | p<0.001 |

Data drawn from National Long-Term Care Survey / Informal Care Survey data from 1999 (n= 791 dyads) and 2004 (n=1149 dyads), and National Health and Aging Trends Study / National Survey of Caregiving from 2011 (n= 736 dyads) and 2015 (n= 746 dyads). Data was weighted using NLTCS and NHATS weights as described in prior work (30). Statistical significance was assessed using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

High caregiving-associated strain was defined on the basis of a cut-point of 5 or greater on a scale of 0–9 based on six elements: caregiver appraisal of the difficulty of helping in three domains – emotional (0 = no difficulty; 1 = some difficulty; 2 = a lot of difficulty), physical (0–2), and financial (0–2) – as well as having no time for oneself (0 = false; 1 = true), being overwhelmed (0 or 1), and being exhausted (0 or 1).

Correlates of High Caregiving Strain

Both dementia and end-of-life status were associated with high caregiving strain in unadjusted logistic regression models (Table 3, middle column). In the full multivariable model that adjusted for older adult and caregiver factors (Table 3, right column) the association of end-of-life status and caregiving strain was attenuated and no longer statistically significant, but the odds of experiencing high strain remained higher among dementia (versus non-dementia) caregivers (aOR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.26–2.22). Aside from dementia, functional status was the only older adult factor that was significantly associated with high caregiving strain in the full multivariable model. Relative to assisting an older adult with 2 or fewer ADLs, assisting an older adult with 3–4 or 5–6 ADLs was associated with a roughly two-fold greater odds of high caregiving strain (aOR=1.77, 95% CI 1.28–2.46 for 3–4 ADLs and 2.55, 95% CI 1.85–3.53 for 56 ADLs).

Table 3.

Simple and Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Examining High Caregiver Strain: Primary Caregivers of Community-Living Older Adults with Self-Care/Mobility Disability

| Unadjusted | Full Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Older Adult Characteristics | ||

| Age | 1.01 [1.00,1.02] | 0.99 [0.97,1.01] |

| Female | 0.69 [0.56,0.86] | 0.93 [0.69,1.27] |

| Black or other race | 0.91 [0.69,1.21] | 0.76 [0.54,1.08] |

| 12+ years of school | 0.69 [0.56,0.85] | 0.92 [0.72,1.18] |

| With Medicaid | 1.24 [1.02,1.51] | 0.98 [0.74,1.31] |

| In fair or poor health | 1.68 [1.34,2.12] | 1.14 [0.88,1.48] |

| Help with ADLs | ||

| Standby, 1, or 2 | REF | REF |

| 3 to 4 | 2.11 [1.60,2.80] | 1.77 [1.28,2.46] |

| 5 to 6 | 3.94 [3.07,5.06] | 2.55 [1.85,3.53] |

| Dementia | 2.36 [1.84,3.03] | 1.67 [1.26,2.22] |

| End of life (EOL) | 1.54 [1.20,1.99] | 1.04 [0.78,1.39] |

| Caregiver Characteristics | ||

| Age | 0.99 [0.99,1.00] | 0.99 [0.98,1.00] |

| Female | 2.37 [1.78,3.16] | 2.15 [1.48,3.14] |

| Relationship to Older Adult | ||

| Spouse | REF | REF |

| Adult child | 1.23 [0.97,1.55] | 0.77 [0.47,1.25] |

| Other | 0.64 [0.48,0.85] | 0.45 [0.27,0.77] |

| Distance to Older Adult | ||

| Co-reside | REF | REF |

| <10 minutes | 0.79 [0.58,1.07] | 0.92 [0.64,1.31] |

| >10 minutes | 0.76 [0.57,1.03] | 0.95 [0.67,1.36] |

| In fair or poor health | 2.61 [2.08,3.28] | 2.65 [2.04,3.45] |

| Employed for pay | 1.18 [0.93,1.50] | 1.50 [1.14,1.97] |

| Greater than 20 hours of caregiving each week | 2.86 [2.19,3.72] | 1.83 [1.37,2.45] |

| Use of respite services | 1.89 [1.40,2.56] | 1.67 [1.17,2.39] |

Data drawn from National Long-Term Care Survey / Informal Care Survey data from 1999 (n= 791 dyads) and 2004 (n=1149 dyads), and National Health and Aging Trends Study / National Survey of Caregiving from 2011 (n= 736 dyads) and 2015 (n= 746 dyads). Data was weighted using NLTCS and NHATS weights as described in prior work (30). The fully adjusted model also accounted for wave of data. High caregiving-associated strain was defined on the basis of a cut-point of 5 or greater on a scale of 0–9 based on six elements: High caregiving-associated strain was defined on the basis of a cut-point of 5 or greater on a scale of 0–9 based on six elements: caregiver appraisal of the difficulty of helping in three domains – emotional (0 = no difficulty; 1 = some difficulty; 2 = a lot of difficulty), physical (0–2), and financial (0–2) – as well as having no time for oneself (0 = false; 1 = true), being overwhelmed (0 or 1), and being exhausted (0 or 1).. Dementia status identified through composite measures as specified in prior work (30, 31). Older adults identified as being at the end of life if they died within a year of survey completion as documented in the Medicare Master Beneficiary File. “Standby” assistance refers to data from the NLTCS only and is grouped with 1–2 self-care/ mobility activities so as to make the NLTCS and NHATS comparable, as previously described (30).

Several caregiver factors were associated with high strain in the fully adjusted multivariable model (Table 3). The likelihood of experiencing high strain was significantly greater among female (versus male) caregivers (aOR=2.15, 95% CI 1.48–3.14), as well as caregivers in poor or fair (versus good or excellent) health (aOR 2.65, 95% CI 2.04–3.45). Caregivers who were employed (aOR=1.50, 95% CI 1.14–1.97) and provided greater than 20 hours of care per week (aOR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.37–2.45) also had a greater odds of high caregiving strain. Caregivers who were not spouses or adult children were less likely to experience high caregiving strain relative to spousal caregivers (aOR=0.45, 95% CI 0.27–0.77).

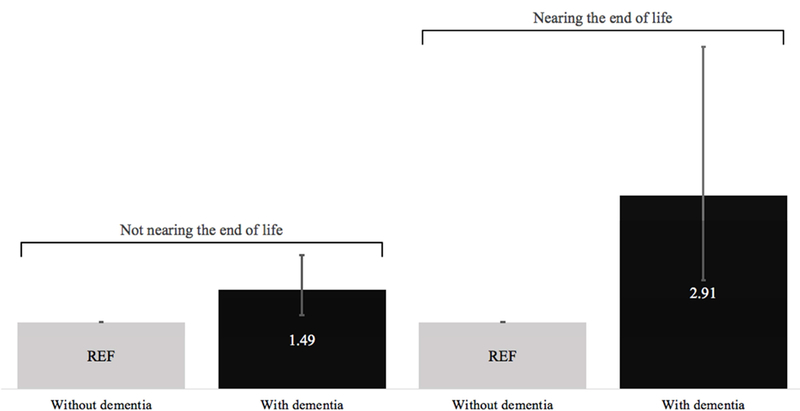

Association of Strain and End-of-Life Status for Dementia Caregivers and for Non-Dementia Caregivers

Dementia remained significantly associated with high caregiving strain in a third model that interacted dementia and end-of-life status and controlled for older adult and caregiver factors (Supplementary Tables 1 & 2). In this model, the association of dementia and caregiving strain was stronger for older adults nearing the end of life (Figure 2). Focusing specifically on dementia caregivers, the odds of high caregiving strain was nearly two-fold higher (aOR=1.94, 95% CI 1.10–3.45) for those assisting an older adult nearing (versus not nearing) end of life (See Supplementary Table 2 for more details on how this ratio was computed). Among non-dementia caregivers, the odds of high caregiving strain was not significantly different by virtue of whether they were approaching end of life.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of High Caregiving Strain within Older Adult End-of-Life Status Strata

DISCUSSION

This study used nationally representative data to determine whether caregiving strain increases among dementia caregivers as older adults approach the end of life, and secondarily, whether there is an association of high strain and end-of-life status among non-dementia caregivers. We found that dementia caregivers were more likely to experience high caregiving strain as older adults near end of life. For those caring for older adults without dementia, the end-of-life period was not associated with increased strain. In addition to dementia status, other factors that were independently associated with increased odds of high caregiving strain included greater functional impairment among older adults, and among caregivers: being female, employed, and providing greater than 20 hours of care.

Our findings are consistent with evidence of the disproportionate impact of dementiarelated caregiving (5,7,35), and expert opinion that has endorsed the notable challenges of caring for persons with dementia and at the end of life (36–38). In prior work, Ornstein et al described the higher prevalence of physical difficulty among caregivers of older adults with dementia at the end of life compared to caregivers of older adults with dementia prior to the end-of-life (29). Our analysis differs from this earlier work in several ways. First, it examines the experiences of primary caregivers (rather than all caregivers) to older adults with mobility or self-care disability, a subset that is at greater risk of caregiving strain. Our study also builds on this prior research by examining correlates of high caregiving strain in multivariable models. These correlates may serve as the basis for intervention research and efforts to alleviate role-related strain through supportive policies and programs.

Despite the apparent challenges of the end-of-life period in dementia, caregiver and care recipient needs, and how to best mitigate them, are not well-described (23,39–41). A recent systematic review determined that 7 of 11 international Clinical Practice Guidelines for dementia care had minimal or no discussion of end-of-life care, with only one specifically recommending a conversation about a person’s preferences on place of death (42). In addition, older adults with dementia and their families are no more likely to receive government or insurance support for paid caregivers at the end of life than prior to this period, in contrast to other medical conditions (29). How and when clinicians engage family members with decision-making around end-of-life care in patients with dementia has been shown to affect what decisions are made, what care is provided, and how family members conceive of their role (43–45), but a robust understanding of the ways in which clinicians interact with patients and families on these matters, and how they could do it better, is lacking. Our study joins the accumulating body of evidence that this is an area of utmost public health importance.

The need for interventions for this caregiver population, however, begs the question of how best to identify them. Prognosticating death in patients with dementia is well-known to be difficult, with a disease trajectory less predictable than for other conditions (14,46,47). In one study of nursing home residents with advanced dementia, for example, only 1% of the 883 residents were predicted to die within six months, but 71% of them actually did (48). In contrast, another study documented that 44% of a sample of 165 community members with dementia who met criteria for hospice (including a prognosis of less than six months) did not die within the sixmonth period (49). Strategies for supporting caregivers of older adults with dementia throughout disease progression – such as caregiver assessment, family engagement, and expanding access to palliative care – bypass this prognostication problem. Caregiver assessment refers to the systematic determination of caregiver ability and willingness to assist a care recipient (36,37,50), and this assessment is part of the process of family engagement through which family members are involved as active members of the healthcare team (51). Both caregiver assessment and engagement dovetail with early and iterative advance care planning with initial diagnosis of cognitive impairment (52), and the approach of palliative care, which prioritizes communication and psychosocial support for patients and families (42). Although challenging, there is an increasing need to expand palliative care for those with dementia for the benefit of both those with the disease and those who care for them (53).

Beyond our findings about the relationship of caregiving strain, and dementia and end-oflife status, other results merit comment as they provide useful insight for targeting high risk caregivers and tailoring interventions for characteristics associated with high strain. Our finding that caregiver strain was associated with severity of older adults’ functional impairment is consistent with prior work (8), and supports the need for more practical interventions to ameliorate burdens of providing hands-on assistance with activities of daily living. Similarly, our finding that strain was higher among female caregivers is consistent with prior literature (8,54) and forthcoming systematic review (55), and is particularly salient in light of the association of financial strain and mortality (56,57) and the continuing predominance of women as dementia caregivers (3). Our finding that caregiver employment is associated with an increased odds of high strain supports the growing policy interest in developing “caregiver-friendly” workplace policies (58–60), as caregiving strain could be reduced by more supportive policies at work.

Strengths of our study include the prospective collection of data and the linked nature of older adult and caregiver surveys. Most studies of caregiving at the end of life rely on followback surveys in which the decedent’s family members are asked to reflect on the time prior to the patient’s death (61). Retrospective data collection of this manner is subject to recall bias, as family members may over- or underestimate the degree of strain they experienced. This study is the first, to our knowledge, that uses nationally representative data to consider how strain varies by both dementia and end of life status in a nationally representative sample of communitydwelling older adults needing assistance with self-care and indoor mobility.

Our study had limitations. The sample population was restricted to older adults greater than 65 years, living in the community, and receiving assistance from a “primary” family or unpaid caregiver helping with self-care and indoor mobility. It is not clear to what extent the results could be generalized to caregivers of older adults without disability, to older adults not living at home, or adults who died prior to the age of 65. Our analysis is also limited by available measures. In particular, we were unable to account for caregiver depression, use of palliative care, personal rewards associated with caregiving, whether the older adult had additional paid inhome help in addition to their “primary caregiver,” and the availability of additional family or unpaid family caregivers other than the “primary caregivers” included in the analysis. Caregiver coping mechanisms were not assessed in either survey, despite evidence that it is caregiver psychological qualities and resilience that most affects the caregiver’s experience of caregiving (62). In addition, our definition of end of life as within the last year of life, though based on prior work (15,33,63–65), may not correspond to what older adults and caregivers subjectively experience as the end-of-life period. For example, a recent mixed methods study reported that family members of recently deceased patients – nearly half of whom had dementia – identified the end-of-life period as starting a median of 3.25 years prior to death (66). Defining the end-of-life period in research is challenging, as definitions may differ according to disease trajectory, study design, and outcomes of interest (27,67).

Our study has important implications for policy and resource allocation. Caregiver experience affects outcomes such as older adult hospitalization (68,69), Medicare spending (69), nursing home placement (70), neuropsychiatric symptoms (71), and emotional distress at the end of life (72), and caregiver personal healthcare costs and acute care utilization (73,74). This context and our findings thus suggest that the continued refinement of interventions for caregivers of persons with dementia throughout the disease trajectory would benefit both caregivers and those for whom they provide care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1. Funding sources: This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (U01AG032947 and R01AG047859) and the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which was funded in-part by Grant Number TL1 TR001078 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The sponsors of this research were not involved in its study concept or design, recruitment of subjects or acquisition of data, data analysis or interpretation, or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

2. Prior presentation: A portion of this work was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Clinical and Translational Science (April 2018).

3. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Judith B. Vick, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Edward D. Miller Research Building, 733 North Broadway, Suite 137, Baltimore, MD 21205-2196.

Katherine A. Ornstein, Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Institute for Translational Epidemiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, One Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1070, 1425 Madison Avenue 3rd Floor, Suite L3-61, New York, NY 10029.

Sarah L. Szanton, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, 525 North Wolfe Street #424, Baltimore, MD 21205-2110.

Sydney M. Dy, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 609, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Jennifer L. Wolff, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 North Broadway, Room 692, Baltimore, MD 21205.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Suchindran C, Reed P, Wang L, Boustani M, et al. The Public Health Impact of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2000–2050: Potential Implication of Treatment Advances. Annu Rev Public Heal 2002;23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weuve J, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Deaths in the United States among persons with Alzheimer’ s disease (2010– 2050). Alzheimer’s Dement [Internet] 2014;10(2):e40–6. Available from: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riffin C, Ness PH Van, Wolff JL, Fried T. Family and Other Unpaid Caregivers and Older Adults without Dementia and Disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;1821–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz R, Martire LM. Family Caregiving of Persons With Dementia: Prevalence, Health Effects, and Support Strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;12(3):240–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y, Schulz R. Family Caregivers’ Strains: Comparative Analysis of Cancer Caregiving with Dementia, Diabetes, and Frail Elderly Caregiving. J Aging Health 2008;1973:483–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dassel KB, Carr DC, Vitaliano P. Does Caring for a Spouse With Dementia Accelerate Cognitive Decline? Findings From the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist 2015;57(2):319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia On Family And Unpaid Caregiving To Older Adults. Health Aff 2015;34(10):1642–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver Burden: A Clinical Review. J Am Med Assoc 2014;311(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harding R, Gao W, Jackson D, Pearson C, Murray J, Higginson IJ. Comparative Analysis of Informal Caregiver Burden in Advanced Cancer, Dementia, and Acquired Brain Injury. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet] 2015;50(4):445–52. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vick JB, Amjad H, Smith KC, Boyd CM, Gitlin LN, Roth DL, et al. “Let him speak:” a descriptive qualitative study of the roles and behaviors of family companions in primary care visits among older adults with cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;33(1):e103–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braungart E, Femia EE, Zarit SH. Resistiveness to care during assistance with activities of daily living in non-institutionalized persons with dementia: associations with informal caregivers’ stress and well-being. Aging Ment Health 2016;20(9):888–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornton M, Travis SS. Analysis of the Reliability of the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol Soc Sci 2003;58(2):127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yates ME, Tennstedt S, Chang B- H. Contributors to and Mediators of Psychological Well-Being for Informal Caregivers. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci [Internet] 1999;54B(1):P12–22. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/articlelookup/doi/10.1093/geronb/54B.1.P12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Jones RN, Prigerson HG, et al. The Clinical Course of Advanced Dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahoney D, Ph D, Allen RS, Ph D, Zhang S, Thompson L, et al. End-of-Life Care and the Effects of Bereavement on Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes TB, Black BS, Albert M, Gitlin LN, Johnson DM, Lyketsos CG, et al. Correlates of objective and subjective measures of caregiver burden among dementia caregivers: Influence of unmet patient and caregiver dementia-related care needs. Int Psychogeriatrics 2014;26(11):1875–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal Care for Persons with Advanced Dementia in the Nursing Home and Home Care Settings. J Palliat Med [Internet] 2004;7(6):808–16. Available from: http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachs GA, Shega JW. Barriers to Excellent End-of-life Care for Patients with Dementia Is Dementia a Terminal Illness? J Gen Intern Med 2004;1919(Mc 6098):1057–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aminoff BZ, Adunsky A. Dying dementia patients: Too much suffering, too little palliation. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2004;19(4):243–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison RS, Sui AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. J Am Med Assoc 2000;284(1):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hebert RS, Arnold RM, Schulz R. Improving Well-Being in Caregivers in Terminally Ill Patients. Making the Case for Patient Suffering as a Focus for Intervention Research. J Pain Symptom Manag 2007;34(5):539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazzan AA, Ploeg J, Shannon H, Raina P, Oremus M. Association between caregiver quality of life and the care provided to persons with Alzheimer’s disease: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 2013;2(17):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies N, Maio L, Rait G, Iliffe S. Quality end-of-life care for dementia: What have family carers told us so far? A narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2014;28(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broady TR, Saich F, Hinton T. Caring for a family member or friend with dementia at the end of life: A scoping review and implications for palliative care practice. Palliat Med 2018;32(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peacock SC. The experience of providing end-of-life care to a relative with advanced dementia: An integrative literature review. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:155–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funk L, Stajduhar K, Toye C, Aoun S, Grande C, Todd C. Part II: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published qualitative. Palliat Med 2010;24(6):594–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stajduhar K, Funk L, Toye C, Grande G, Aoun S, Todd C. Part I: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008). Palliat Med 2010;24(6):573–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Birchley G, Jones K, Huxtable R, Dixon J, Kitzinger J, Clare L. Dying well with reduced agency: a scoping review and thematic synthesis of the decision-making process in dementia, traumatic brain injury and frailty. BMC Med Ethics [Internet] 2016;17(46):1–15. Available from: 10.1186/s12910-016-0129-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornstein KA, Kelley AS, Bollens-lund E, Wolff JL, Ornstein BKA, Kelley AS, et al. A National Profile of End-of-Life Caregiving in the United States. Health Aff 2017;36(7):1184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolff JL, Mulcahy J, Huang J, Roth DL, Covinsky K, Kasper JD. Family Caregivers of Older Adults, 1999 – 2015: Trends in Characteristics, Circumstances, and Role-Related Appraisal. Gerontologist 2017;00(00):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study: Technical Paper #5 Baltimore; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Care E, Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, Kasper JD. End-of-Life Care: Findings from a National Survey of Informal Caregivers. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wachterman MW, Sommers BD. The Impact of Gender and Marital Status Mortality Follow-Back Survey. J Palliat Med 2006;9(2):343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolff JL, Mulcahy J, Roth D, Cenzer I, Kasper JD, Huang J, et al. Long-Term Nursing Home Entry: A Prognostic Model for Older Adults with a Family or Unpaid Caregiver. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;Epub ahead. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ory MG, Iii RRH, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and Impact of Caregiving: A Detailed Comparison Between Dementia and Nondementia Caregivers. Gerontologist 1999;39(2):177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz R, Czaja SJ. Family Caregiving: A Vision for the Future. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry [Internet] 2018;26(3):358–63. Available from: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The National Academies of Science Engineering & Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America, A Report of The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shanley C, Russell C, Middleton H, Simpson-young V. Living through end-stage dementia: The experiences and expressed needs of family carers. Dementia 2011;10(3). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrar KM, Schmidt H, Eisenmann Y, Cremer B, Voltz R. Needs of People with Severe Dementia at the End-of-Life: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2015;43:397–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson GN, Roger K. Understanding the needs of family caregivers of older adults dying with dementia. Palliat Support Care 2014;12(3):223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson EW, White KM. “It Has Changed My Life”: An Exploration of Caregiver Experiences in Serious Illness. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2018;35(2):266–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durepos P, Wickson-griffiths A, Hazzan AA, Kaasalainen S, Vastis V, Battistella L. Assessing Palliative Care Content in Dementia Care Guidelines: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet] 2017;53(4):804–13. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caron CD, Griffith J, Arcand M. End-of-life decision making in dementia: the perspective of family caregivers. Dementia 2005;4(1):113–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicholas HL, Bynum JPW, Iwashyna JT, Weir RD, Langa MK, Nicholas LH, et al. Advance Directives And Nursing Home Stays Associated With Less Aggressive End-Of-Life Care For Patients With Severe Dementia. Health Aff [Internet] 2014;33(4):667– 74. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24711329%5Cnhttp://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=2012544843&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waldrop DP, Kramer BJ, Skretny JA, Milch RA, Finn W. Final Transitions: Family Caregiving at the End of Life. J Palliat Med 2005;8(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Covinsky KE, Yaffe K. Dementia, Prognosis, and the Needs of Patients and Caregivers. Ann Intern Med 2004;140(7):573–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. The Advanced Dementia Prognostic Tool (ADEPT): A Risk Score to Estimate Survival in Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia. J Pain Symptom Manag 2010;40(5):639–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying With Advanced Dementia in the Nursing Home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schonwetter RS, Han B, Small BJ, Martin B, Tope K, Haley WE. Predictors of six-month survival among patients with dementia: An evaluation of hospice Medicare guidelines. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2003;20(2):105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolff JL, Feder J, Schulz R. Supporting Family Caregivers of Older Americans. N Engl J Med 2016;375(26):2513–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, Sofaer S, Adams K, Bechtel C, et al. Patient and Family Engagement. Heal Aff 2013;32(2):223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas J, Sanchez-Reilly S, Bernacki R, Neill LO, Morrison LJ, Kapo J, et al. Advance Care Planning in Cognitively Impaired Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ornstein KA, Schulz R, Meier DE. Families Caring for an Aging America Need Palliative Care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(4):877–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgan T, Williams LA, Trussardi G. Gender and family caregiving at the end-of-life in the context of old age :A systematic review. Palliat Med 2016;30(7):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong C, Biscardi M, Nalder E, Colantonio A. Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open [Internet] 2018;8(8):e022779 Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shippee TP, Wilkinson LR, Ferraro KF. Accumulated Financial Strain and Women’s Health Over Three Decades. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2012;67(September):585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szanton SL, Allen JK, Thorpe RJ, Seeman T, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Effect of Financial Strain on Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Women. Journals Gerontol Soc Sci 2008;63B(6):369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arora K, Wolf DA. Does Paid Family Leave Reduce Nursing Home Use? The California Experience. Jounral Policy Anal Manag 2018;37(1):38–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feinberg LF. Breaking New Ground: Supporting Employed Family Caregivers with Workplace Leave Policies. AARP Public Policy Inst 2018;136(September):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner G California’s Paid Leave Helped My Patient. Health Aff 2018;37(9):1524–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teno JM. Measuring End-of-Life Care Outcomes Retrospectively. J Palliat Med 2005;8:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burton AM, Sautter JM, Tulsky JA, Lindquist JH, Hays JC, Olsen MK, et al. Burden and Well-Being Among a Diverse Sample of Cancer, Congestive Heart Failure, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet] 2012;44(3):410–20. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD, Kasper JD. End-of-Life Care: Findings from a National Survey of Informal Caregivers. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ornstein KA, Kelley AS, Bollens-lund E, Wolff JL, Ornstein BKA, Kelley AS, et al. A National Profile of End-of-Life Caregiving in the United States. Health Aff 2017;7(7):1184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singer AE, Meeker D, Teno JM, Lynn J, Lunney JR, Lorenz KA. Symptom trends in the last year of life from 1998 to 2010: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(3):175–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen-Mansfield J, Cohen R, Skornick-Bouchbinder M, Brill S. What Is the End of Life Period? Trajectories and Characterization Based on Primary Caregiver Reports. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73(5):695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of elderly Medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sadak T, Zdon SF, Ishado E, Zaslavsky O, Borson S. Potentially preventable hospitalizations in dementia: family caregiver experiences. Int Psychogeriatrics 2017;29(7):1201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ankuda CK, Maust DT, Kabeto MU, Mccammon RJ, Langa KM, Levine DA. Association Between Spousal Caregiver Well-Being and Care Recipient Healthcare Expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cepoiu-martin M, Tam-tham H, Patten S, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Predictors of longterm care placement in persons with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:1151–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sink KM, Covinsky ÃKE, Barnes DE, Newcomer RJ, Yaffe K. Caregiver Characteristics Are Associated with Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soto-Rubio A, Pérez-Marín M, Barreto P. Frail elderly with and without cognitive impairment at the end of life: Their emotional state and the wellbeing of their family caregivers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr [Internet] 2017;73(July):113–9. Available from: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilden DM, Kubisiak JM, Kahle-wrobleski K, Ball DE, Bowman L. Using U.S. Medicare records to evaluate the indirect health effects on spouses: a case study in Alzheimer’s disease patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14(291):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Hui S, Hendrie HC. Acute Care Utilization by Dementia Caregivers Within Urban Primary Care Practices. J Gen Intern Med 2008;11:1736–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.