Abstract

Objective:

To investigate differences in facility characteristics, patient characteristics, and outcomes between skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) that participated in Medicare’s voluntary Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative and non-participants, prior to BPCI.

Design:

Retrospective, cross-sectional comparison of BPCI participants and non-participants.

Setting:

SNFs

Participants:

All Medicare-certified SNFs (n = 15,172) and their 2011–2012 episodes of care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, femur and hip/pelvis fracture, hip and femur procedures, lower extremity joint replacement, and pneumonia (n = 873,739).

Interventions:

Participation in a bundled payment program that included taking financial responsibility for care within a 90 day episode.

Main Outcome Measures:

This study investigates the characteristics of bundled payment participants and their patient characteristics and outcomes relative to non-participants prior to BPCI, to understand the implications of a broader implementation of bundled payments.

Results:

SNFs participating in BPCI were more likely to be in urban areas (80.8–98.4% versus 69.5%) and belong to a chain or system (73.8–85.5% versus 55%), and were less likely to be located in the south (13.1–20.2% versus 35.4%). Quality performance was similar or higher in most cases for SNFs participating in BPCI relative to non-participants. In addition, BPCI participants admitted higher socioeconomic status patients with similar clinical characteristics. Initial SNF length of stay was shorter and hospital readmission rates were lower for BPCI patients compared to non-participant patients.

Conclusions:

We found that SNFs participating in the second financial risk-bearing phase of BPCI represented a diversity of SNF types, regions, and levels of quality and the results may provide insight into a broader adoption of bundled payment for post-acute providers.

Keywords: Medicare, Health Care Reform, Quality of Health Care

Medicare is testing new health care payment and delivery models to improve efficiency and quality. Many of these programs, including the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, are voluntary. BPCI consisted of four payment models aimed at reducing Medicare spending and improving quality of care. Models 2 and 3 made up the majority of participants (1). Under Model 3, primarily SNFs and a smaller number of other post-acute care provider participants initiated episodes of bundled payment following hospitalization for an episode lasting up to 90 days after post-acute care initiation (2). Providers could participate as either Awardees or Episode Initiators. Awardees took on financial risk for their episodes while Episode Initiators did not necessarily bear risk.

Proponents of voluntary demonstrations argue that they facilitate real-time refinement and face less attrition (3, 4). Others argue that mandatory randomized participation would provide more robust evidence (3, 5). Medicare has chosen to primarily rely on voluntary participation in its bundled payment programs including the BPCI initiative, which is the subject of this study and will conclude in September 2018, and BPCI Advanced, which is similar to Model 2 and will begin in October 2018 (6). Voluntary participants may differ from non-participants based on observable and unobservable attributes that may limit generalizability. For example, BPCI participants may be those with the care coordination tools and infrastructure to take on risk. Year 3 results of BPCI found that lower extremity joint replacement Medicare payments declined for Model 3 SNF participants and overall quality of care impact was mixed, but it is not clear whether these findings are generalizable (7).

This study investigates differences in provider characteristics, patient characteristics, and patient outcomes between SNFs participating in BPCI Model 3 and non-participant SNFs prior to the initiation of the program, in order to better understand whether the results of the pilot are likely to occur with a broader adoption of bundled payment.

Methods

BPCI Program

Medicare announced the first set of organizations selected to participate in the voluntary BPCI initiative on January 31, 2013 and participation began on October 1, 2013. Additional cohorts began participating throughout 2014 and 2015 (2). Participants chose from up to 48 clinical conditions, defined by the Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) from the episode initiating hospitalization. The BPCI initiative included two phases, Phase 1 and Phase 2. Under Phase 1, the preparation period, BPCI participants did not bear financial risk. BPCI participants transitioned at least one clinical episode to Phase 2 by July 2015. Phase 1 concluded in September 2015, at which point all participants transitioned to the risk-bearing Phase 2 (1). Under Phase 2, payments during the episode were retrospectively compared to a participant specific, MS-DRG target price, which was set using a 2% discount on historical payments. Entities bearing financial risk kept net gains above the target and paid Medicare back for net losses. Thus, there was an incentive to deliver more efficient care.

Participants

We identified Model 3 SNF participants using the most recent list of BPCI participants published by Medicare on January 1, 2018. We investigated two levels of Model 3 SNF participation: Awardees or Episode Initiators. In Phase 2, Awardees received savings or were penalized relative to the target price for episodes that they initiated or that were triggered by affiliated Episode Initiators. Episode Initiators triggered episodes for their affiliated Awardee, but did not necessarily take on risk (1). BPCI allowed Awardees to apply for “gainsharing” waivers through which they shared savings with Episode Initiators or other providers if spending fell below target prices. However, BPCI year 3 results found that only 6.5% of Model 3 Awardees implemented these gainsharing agreements (7). As of January 2018, there were 663 participants in Model 3, including 85 Awardees and 578 Episode Initiators (2). We identified 61 SNF Awardees and 489 SNF Episode Initiators, which represent 83% of Model 3 participants. The remaining 17% of participants were home health agencies, inpatient rehabilitation facilities and physician group practices that we excluded from the analysis (2). All other SNFs that were not categorized as Awardees or Episode Initiators were considered non-participants (n 14,622). The study includes all 15,172 Medicare certified SNFs as of 2013.

Episode Definition

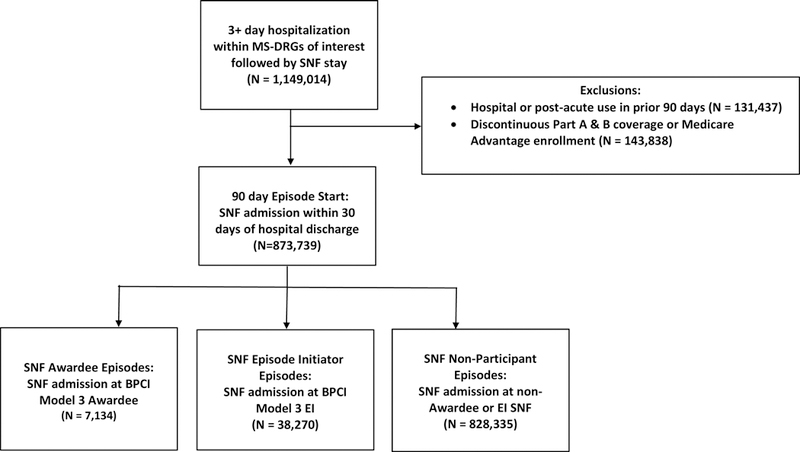

We identified 2011–2012 pre-BPCI SNF episodes in the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file. We constructed 90-day episodes of care that were initiated by a SNF admission. Although, not included in the bundled payment episode, each SNF admission must be preceded by a hospital stay within one of the 48 clinical conditions, which determines the payment amount. We excluded episodes with hospital discharges or post-acute care use in the 90-days prior to SNF admission. We also excluded episodes where a patient exhibited either discontinuous Part A or B coverage or Medicare Advantage enrollment during the year(s) spanning a 90-day pre-episode period and the 90-days following SNF admission. We limited episodes to high volume MS-DRGs, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, femur and hip/pelvis fractures, hip and femur procedures, lower extremity joint replacement, and pneumonia (7, 8). Our analysis included 7,134 Awardee episodes, 38,270 Episode Initiator episodes, and 828,335 non-participant episodes. Further description of the study sample selection process can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Sample Selection Flow Chart

Study Measures

Provider Characteristics

We obtained pre-BPCI SNF facility information from the 2013 Medicare Provider of Services file (9). This included indicators for urban or rural location, profit status (for-profit, non-profit, or other), and health system affiliation, as well as number of Medicare certified beds. We identified SNF region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West) using information from the U.S. Census Bureau (10). We obtained Medicare and Medicaid patient share information from the LTC focus dataset (11). We used pre-BPCI quality information from the 2012 Nursing Home Compare file. We created indicator variables for whether SNFs received 5 or 4/5 out of five stars on monthly ratings and then calculated the percent of months that met these criteria for the following Nursing Home Compare composite quality measures: overall rating, survey rating (based on deficiencies identified during annual inspections), quality rating (based on 11 physical and clinical measures), level of overall nurse staffing, and level of registered nurse staffing (12). The Nursing Home Compare Five Star Quality Rating System is a validated and commonly used assessment of nursing home quality and distinguishing facilities with 5 star or 4/5 star ratings identifies those facilities with the highest levels of quality (13, 14). We compared the facility characteristics and quality ratings of Model 3 Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs to non-participants prior to BPCI.

Patient Characteristics

We identified pre-BPCI patient demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics from the initial hospitalization, and SNF admission assessment clinical characteristics from the Master Beneficiary Summary Files, the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review Files, and the Minimum Data Set respectively. Patient demographic characteristics included age, gender, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Medicaid coverage, eligibility for the Part D low-income subsidy). Clinical characteristics from the preceding hospitalization included the length of the hospital stay, the comorbidities listed on the hospital claim (15), whether the MS-DRG for the hospital stay included complications or comorbidities, and whether the hospitalization included time in the intensive care unit. Patient characteristics from the SNF admission assessment included the late loss activities of daily living (ADL) scale, which is a 16-point scale based on bed mobility, transfer, toilet use and eating (16), and the long form ADL scale, which is a 28-point scale including measures for bed mobility, transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toilet use and personal hygiene (17). For both the late loss ADL scale and the long form ADL scale, a higher score indicates greater impairment. We also identified presence of the following conditions on admission using the Minimum Data Set: comatose, Alzheimer’s disease,stroke, heart failure, cancer, diabetes, and depression.

SNF Episode Outcomes

We constructed patient-level outcomes for 90-day episodes of care that began with a SNF admission prior to BPCI participation. Outcomes included initial SNF length of stay and whether a patient was readmitted to a hospital within the 90-day episode.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses to assess differences in provider characteristics, patient characteristics, and outcomes between Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants, prior to BPCI. We calculated unadjusted provider characteristics and Nursing Home Compare quality ratings means and standard deviation (for continuous variables only) separately for Awardee, Episode Initiator, and non-participant SNFs. We also calculated 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile values for continuous provider characteristics, to account for potential non-normal distributions. To compare both Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs to non-participant SNFs, we estimated differences in provider characteristics and Nursing Home Compare quality measures for Awardee SNFs versus non-participant SNFs and Episode Initiator SNFs versus non-participant SNFs. To achieve this, we ran regressions with separate indicator variables for Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs with non-participants as the omitted category. Standard errors were clustered at the hospital referral region level (18). We then interpreted differences in means and p-values on the Awardee and Episode Initiator indicator variable coefficients to identify whether Awardee characteristics and Episode Initiator characteristics respectively were significantly different from non-participants.

We calculated unadjusted means and standard deviations (continuous variables only) for patient demographic characteristics, characteristics of the preceding hospital stay, and SNF admission assessment clinical characteristics separately for Awardees and Episode Initiators compared to non-participants prior to BPCI initiation. We also identified the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile for continuous patient characteristic variables to better display their underlying distribution. To assess differences across provider groups, we ran regressions on each demographic or clinical characteristic with separate indicator variables for Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs with non-participants as the omitted category. We included fixed effects for the MS-DRG from the preceding hospital stay in the demographic and clinical characteristic regressions to assess within MS-DRG differences between provider groups. Standard errors were clustered at the SNF provider level. We used mean differences and the p-values on the Awardee and Episode Initiator indicator variables to determine whether there were statistically significant within MS-DRG differences in patient characteristics between Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants respectively. When assessing differences in the presence of comorbidity or complication in the initiating hospitalization, we assessed within condition differences rather than within MS-DRG differences since presence of comorbidity or complication does not vary at the MS-DRG level. For example, lower extremity joint replacement includes two MS-DRGs one without major complication or comorbidity (470) and the other with major complication or comorbidity (469). For the comorbidity or complication analysis, we aggregated these episodes into one lower extremity joint replacement condition group and flagged episodes with complication or comorbidity. We applied the same approach for each clinical condition.

In our final analysis, we assessed differences in patient outcomes (SNF length of stay and hospital readmission) between Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants prior to BPCI initiation. To account for observable differences in the patients admitted to BPCI participant SNFs, we estimated adjusted differences between Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants using multivariate regressions that adjusted for patient demographic and clinical characteristics. We adjusted for the previously mentioned patient demographic and clinical characteristics as well as flags for individual Elixhauser comorbidities and MS-DRG (15). For each outcome, we estimated multivariate linear regressions that included separate indicator variables for Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs with non-participants as the omitted category. We calculated standard errors clustering at the SNF provider level. Adjusted means for the three provider groups and adjusted differences (including 95% confidence intervals) between Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants were determined using regression estimates. We interpreted magnitude of adjusted differences and p-values on the Awardee and Episode Initiator indicator variable coefficients to determine whether Awardee outcomes and Episode Initiator outcomes were significantly different from non-participants.

Results

Table 1 compares provider characteristics and quality ratings of Awardees (n=61), Episode Initiators (n=489), and non-participating SNFs (n=14,622) prior to BPCI initiation. Awardee SNFs were more likely to be located in an urban area (98.4% versus 69.5%), were more likely to be non-profit (42.6% vs 24.6%), and were larger (141.8 vs 107.2 beds) relative to non-participants. Awardees were more often located in the Northeast (27.9% versus 17.1%) or West (26.2% versus 15.1%) and less often located in the South (13.1% versus 35.4%) compared to non-participant SNFs. Awardees were substantially more likely to exhibit 4 or 5 stars on Nursing Home Compare quality (65.2% versus 48.5%) and registered nurse staffing ratings (67.2% versus 41.3%) compared to non-participants prior to BPCI participation. Differences in overall, survey, and staffing ratings were not large or significantly different between Awardees and non-participants before BPCI. Episode Initiators were more likely to be located in an urban area (80.8% versus 69.5%), be for-profit (85.1% versus 69.9%), and belong to a SNF chain or system (85.5% versus 55.0%) relative to non-participants. The regional location of Episode Initiators was similar to Awardees. Quality ratings were similar between Episode Initiators and non-participants prior to BPCI. When comparing means to 25th percentiles, medians, and 75th percentiles, we found that provider characteristics were symmetrically distributed while the distribution for quality ratings was typically left skewed across the three provider groups.

Table 1.

Skilled nursing provider characteristics and quality by BPCI Participation

| Awardees (N=61) |

Episode Initiators (N=489) |

Non-Participants (N=14,622) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | P-value | Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | P-value | Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | ||

| Provider Characteristics | |||||||||

| Rural-Urban | |||||||||

| Urban (%) | 98.4* | N/A | 0.001 | 80.8* | N/A | 0.001 | 69.5 | N/A | |

| Rural (%) | 1.6* | N/A | 0.001 | 19.2* | N/A | 0.001 | 30.5 | N/A | |

| Ownership | N/A | ||||||||

| For-Profit (%) | 57.4 | N/A | 0.136 | 85.1* | N/A | <0.001 | 69.9 | N/A | |

| Non-Profit (%) | 42.6* | N/A | 0.026 | 14.3* | N/A | 0.001 | 24.8 | N/A | |

| Other (%) | 0.0* | N/A | 0.002 | 0.6* | N/A | <0.001 | 5.3 | N/A | |

| Region | |||||||||

| Northeast (%) | 27.9 | N/A | 0.173 | 25.2 | N/A | 0.060 | 17.1 | N/A | |

| Midwest (%) | 32.8 | N/A | 0.963 | 33.5 | N/A | 0.802 | 32.3 | N/A | |

| South (%) | 13.1* | N/A | 0.002 | 20.2* | N/A | <0.001 | 35.4 | N/A | |

| West (%) | 26.2 | N/A | 0.151 | 21.1 | N/A | 0.103 | 15.1 | N/A | |

| Other | |||||||||

| In a Health System (%) | 73.8 | N/A | 0.078 | 85.5* | N/A | <0.001 | 55.0 | N/A | |

| Medicare certified beds count | 141.8*(73.5) | (101,125,160) | <0.001 | 107.2(46.0) | (73,100,130) | 0.986 | 107.2(61.6) | (64,100,128) | |

| Percent Medicare patients (%) | 19.8(16.0) | (6.6,15.0,30.9) | 0.125 | 19.0*(16.0) | (9.8,15.0,22.3) | 0.001 | 16.0(15.4) | (7.1,12.0,19.2) | |

| Percent Medicaid patients (%) | 55.6(15.7) | (49.0,59.6,66.0) | 0.117 | 55.9*(20.9) | (47.2,60.7,68.9) | 0.005 | 59.5(23.1) | (49.6,64.1,75.6) | |

| NHC Quality Ratings | |||||||||

| Overall Rating | |||||||||

| 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 18.2(32.0) | (0.0,0.0,33.3) | 0.701 | 15.0(29.8) | (0.0,0.0,8.3) | 0.280 | 16.6(31.7) | (0.0,0.0,16.7) | |

| 4 or 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 44.6(46.7) | (0.0,20.8,100.0) | 0.843 | 43.1(42.8) | (0.0,37.5,100) | 0.784 | 43.6(43.7) | (0.0,33.3,100.0) | |

| Survey Rating | |||||||||

| 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 6.8(23.3) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.212 | 8.6(25.6) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.115 | 10.5(28.1) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | |

| 4 or 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 26.8(41.6) | (0.0,0.0,66.7) | 0.243 | 34.6(43.4) | (0.0,0.0,91.7) | 0.934 | 34.2(43.8) | (0.0,0.0,100.0) | |

| Quality Rating | |||||||||

| 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 24.0(32.7) | (0.0,0.0,50.0) | 0.175 | 16.5(27.6) | (0.0,0.0,25.0) | 0.931 | 16.6(28.4) | (0.0,0.0,25.0) | |

| 4 or 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 65.2*(37.4) | (41.7,75.0,100.0) | 0.014 | 49.8(37.8) | (0.0,50.0,100.0) | 0.610 | 48.5(38.6) | (0.0,50.0,100.0) | |

| Staffing Rating | |||||||||

| 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 13.3(28.9) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.472 | 5.0*(18.6) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | <0.001 | 9.3(26.3) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | |

| 4 or 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 61.8(43.7) | (8.3,91.7,100.0) | 0.078 | 43.6(44.5) | (0.0,25.0,100.0) | 0.088 | 49.4(44.8) | (0.0,41.7,100.0) | |

| Registered Nurse Staffing Rating | |||||||||

| 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 23.5(38.0) | (0.0,0.0,36.4) | 0.388 | 15.3(32.2) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | 0.264 | 17.4(34.8) | (0.0,0.0,0.0) | |

| 4 or 5 star (% of SNF/months) | 67.2*(45.1) | (0.0,100.0,100.0) | <0.001 | 40.6(44.4) | (0.0,25.0,100.0) | 0.802 | 41.3(45.2) | (0.0,16.7,100.0) | |

Notes: Table displays mean, standard deviation, 25th percentile, 50th percentile, and 75th percentile of provider characteristics. P-values represents statistical significance of differences between Awardees and Episode Initiators compared to non-participant SNFs. Standard errors clustered at hospital referral region level.

indicates p<0.05.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare Provider of Services File, U.S. Census Bureau, LTC focus, and Nursing Home Compare data.

Table 2 compares patient demographic and clinical characteristics of Awardee, Episode Initiator, and non-participant SNF episodes prior to BPCI initiation. Adjusting for the MS-DRG of the preceding hospital stay, Awardee SNF patients were less likely to be dual eligible for Medicaid or qualify for the Part D low income subsidy compared to non-participant SNF patients (23.2% versus 30.0%) before BPCI. Awardee SNF patients also scored higher on the late loss ADL scale (9.1 versus 8.3) compared to non-participants, which indicates that Awardee patients were more impaired. However, Awardee SNF patients were similar to non-participant SNF patients based on other demographic and clinical variables, both from the preceding hospital stay and SNF admission assessment. Episode Initiator patients were less likely to be dual eligible for Medicaid or qualify for the Part D low income subsidy (23.2% versus 30.0%) and be non-white (7.7% versus 10.8%) relative to non-participants prior to BPCI. No large differences were observed between Episode Initiator patients and non-participant SNF patients in other demographic, preceding hospitalization, or SNF admission assessment characteristics before BPCI. The distribution of continuous patient characteristics was symmetric and means were similar to medians across all three provider groups.

Table 2.

Skilled nursing patient characteristics by BPCI Participation

| Awardees (Episodes=7,134) |

Episode Initiators (Episodes=38,270) | Non-participants (Episodes= 828,335) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | P-Value | Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | P-Value | Mean(SD) | PCTL(25th,50th,75th) | ||

|

Demographics | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 81.3(9.3) | (75,82,88) | 0.102 | 81.1(9.6) | (75,82,88) | 0.058 | 81.1(9.7) | (75,82,88) | |

| Female (%) | 71.8 | N/A | 0.106 | 69.3 | N/A | 0.179 | 69.5 | N/A | |

| Non-white (%) | 12.9 | N/A | 0.363 | 7.7* | N/A | <0.001 | 10.8 | N/A | |

| Medicaid or low income subsidy (%) | 23.2* | N/A | 0.019 | 26.0* | N/A | <0.001 | 30.0 | N/A | |

| Initiating Hospitalization Characteristics | |||||||||

| Length of initiating hospital stay (days) |

5.6(3.6) | (3,4,7) | 0.387 | 5.3*(3.5) | (3,4,6) | <0.001 | 5.5(3.7) | (3,4,6) | |

| Comorbidities (number)1 | 3.2(1.8) | (2,3,4) | 0.636 | 3.2*(1.8) | (2,3,4) | 0.002 | 3.3(1.8) | (2,3,4) | |

| Initiating hospitalization with comorbidity or complication (%) |

52.6 | N/A | 0.122 | 53.3 | N/A | 0.475 | 55.7 | N/A | |

| Initiating hospitalization in intensive care unit (%) |

20.7 | N/A | 0.380 | 20.1 | N/A | 0.246 | 19.9 | N/A | |

| SNF Admission MDS Assessment | |||||||||

| Late loss ADL scale | |||||||||

| (0–16, 16 is most dependent) | 9.1*(4.0) | (6,10,12) | 0.033 | 8.5(4.2) | (6,8,12) | 0.137 | 8.3(4.3) | (5,8,12) | |

| Long form ADL scale | |||||||||

| (0–28, 28 is most dependent) | 17.7(4.0) | (16,19,20) | 0.059 | 17.1(4.2) | (15,18,19) | 0.327 | 17.0(4.5) | (15,18,20) | |

| Comatose (%) | 0.0 | N/A | N/A | 0.0 | N/A | 0.128 | 0.0 | N/A | |

| Alzheimer’s disease (%) | 4.2 | N/A | 0.502 | 4.0* | N/A | 0.006 | 4.6 | N/A | |

| Stroke (%) | 13.9 | N/A | 0.116 | 13.4 | N/A | 0.691 | 13.9 | N/A | |

| Heart failure (%) | 23.2 | N/A | 0.088 | 22.3 | N/A | 0.470 | 23.3 | N/A | |

| Cancer (%) | 6.3 | N/A | 0.615 | 6.1 | N/A | 0.504 | 6.0 | N/A | |

| Diabetes (%) | 27.5 | N/A | 0.668 | 26.0* | N/A | 0.002 | 27.5 | N/A | |

| Depression (%) | 26.0 | N/A | 0.540 | 25.6* | N/A | 0.008 | 27.0 | N/A | |

Notes: Table displays mean, standard deviation, 25th percentile, 50th percentile, and 75th percentile of patient characteristics. P-values represent statistical significance of within-MS-DRG or condition differences between Awardees and Episode Initiators compared to non-participant SNFs. Standard errors clustered at the SNF provider level.

indicates p<0.05.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare claims data, Master Beneficiary Summary File, and Minimum Data Set assessments.

Comorbidities are based on the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, which identifies the number of comorbidities on an inpatient hospital claim

Table 3 compares patient outcomes adjusted for patient demographic and clinical characteristics between Awardee, Episode Initiator, and non-participant SNF episodes prior to BPCI initiation. Adjusted initial SNF length stay and hospital readmission within 90 days were lower for both Awardees and Episode Initiators compared to non-participant SNFs. Initial SNF length of stay was approximately two days lower at Awardee (34.6 days) and Episode Initiator (34.9 days) SNFs relative to non-participants (36.8 days). However, only the Episode Initiator difference was statistically significant. Hospital readmission within 90 days was 0.8% lower for both Awardee and Episode Initiator episodes (24.6% versus 25.4%) but, as with the SNF length of stay analysis, significant differences were only observed for Episode Initiators.

Table 3.

Skilled nursing facility outcomes by BPCI participation

| Awardees (Episodes=7,134) |

Episode Initiators (Episodes=38,270) |

Non-Participants (Episodes=828,335) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | Adjusted difference (relative to non-participants) |

Adjusted | Adjusted difference (relative to non-participants) |

Adjusted | |||||

| Mean | Difference | 95% CI | Mean | Difference | 95% CI | Mean | |||

| Outcomes | |||||||||

| Initial SNF length of stay (days) |

34.6 | −2.2 | (−5.2,0.6) | 34.9 | −1.9* | (−2.8,−1.0) | 36.8 | ||

| Hospital readmission within 90 days (%) |

24.6 | −0.8 | (−2.3,0.7) | 24.6 | −0.8* | (−1.4,−0.1) | 25.4 | ||

Notes: Table displays adjusted mean patient outcomes of 90-day post-discharge episodes and adjusted differences, including 95% confidence interval, for patients admitted to Awardees and Episode Initiators compared to non-participant SNFs controlling for patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Standard errors clustered at SNF provider level.

indicates p<0.05.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare claims data, MDS assessments, and Master Beneficiary Summary File.

Discussion

BPCI Model 3 was a voluntary initiative under which SNFs applied and selected to participate. Randomized evaluations are more likely to produce estimated effects that are both unbiased and generalizable to a broader provider or patient population. Critics of voluntary demonstrations argue that differences in episode costs and outcomes between participants and non-participants may indicate differences in unobservable provider characteristics that would not extend under broader provider participation (19). More specifically, under BPCI Model 3, participating SNFs may have been those that were more likely benefit from participation. Thus, the estimated effects of BPCI Model 3 may not be generalizable to a broader set of facilities.

We found that Awardee SNFs and Episode Initiator SNFs differed from non-participants on a range of structural characteristics, including location, size, profit status, and chain membership. Urban, for-profit SNFs belonging to a health system disproportionately participated in BPCI Model 3 and these types of facilities may be the best equipped to implement bundled payments. Despite these differences, there was still broad, if not proportional, participation of SNFs based on chain membership, for-profit status, size, patient composition, and to a lesser extent urban status. Pre-BPCI Nursing Home Compare quality ratings were fairly similar for Awardees versus non-participants and Episode Initiators versus non-participants.

With respect to pre-BPCI patient characteristics, both Awardees and Episode Initiators admitted higher socioeconomic status patients compared to non-participants. The late loss ADL score indicates that Awardee patients exhibited greater functional dependencies relative to non-participant patients. However, Awardee and Episode Initiator patients were similar to non-participant patients across other demographic and clinical characteristics derived from both the preceding hospital stay and the SNF admission assessment. These findings suggest that BPCI participant SNF patients and non-participant are comparable on observable characteristics.

Both Awardees and Episode Initiators demonstrated shorter initial SNF length of stay and lower rates of hospital readmission within 90 days compared to non-participants prior to BPCI. However, significant differences were only observed for Episode Initiator episodes. To the extent that BPCI encourages improvements in quality and outcomes, this may signal that BPCI widened differences in quality and resource use between some participants and non-participants.

Study Limitations

Voluntary participation in BPCI Model 3 created inherent differences between participants, including both Awardees and Episode Initiators, and non-participants. In addition to observable differences, such as provider characteristics, quality ratings, patient characteristics, and outcomes, there are unobservable differences between participants and non-participants. These unobservable differences make it difficult to predict the impact of broader adoption of bundled payments. Furthermore, this analysis focused on SNF provider characteristics, quality, patient characteristics, and outcomes prior to BPCI initiation. However, if patient characteristics changed after bundled payment program initiation, improved quality and outcomes may not extend to the full patient population.

Conclusion

Awardee and Episode Initiator SNFs participating in Model 3 differed from non-participants, in terms of structural characteristics, patient socioeconomic status, and outcomes prior to BPCI. However, SNF participants in Model 3 represented a diversity of SNF types, regions, and levels of quality and the results may provide insight into a broader adoption of bundled payment for post-acute providers.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Research grant from National Institute on Aging (R01AG046838)

Abbreviations:

- BPCI

(Bundled Payments for Care Improvement)

- MS-DRG

(Medicare severity diagnosis-related group)

- SNF

(skilled nursing facility)

- ADL

(activities of daily living)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Bundl ed Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information,” https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Model 3: Retrospective Post Acute Care Only [Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/BPCI-Model-3/index.html Last Accessed: 2/12/18.

- 3.Kolata G Method of Study Is Criticized in Group’s Health Policy Tests New York Times; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsburg PB, Wilensky GR. Revamping Provider Payment in Medicare. Forum for Health Economics and Policy 2015;18(2):137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Press MJ, Rajkumar R, Conway PH. Medicare’s New Bundled Payments: Design, Strategy, and Evoluation. JAMA 2016;315(2):131–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced [Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced.

- 7.The Lewin Group. CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2–4: Year 3 Evaluation & Monitoring Annual Report 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiative: Most Hospitals Are Focused On A Few High-Volume Conditions. Health Affairs 2015;34(3):371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Provider of Services Current Files [Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Provider-of-Services/index.html

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States [Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

- 11.Brown University Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research. LTCfocus Facility Data 2013. [Available from: http://ltcfocus.org/

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Compare 2016. [Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare.

- 13.Werner RM, Konetzka RT, Kim MM. Quality Inprovement Under Nursing Home Compare: the Association Between Changes in Process and Outcome Measures. Medical Care 2013;51(7):582–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabowski DC, Town RJ. Does Information Matter? Competition, Quality, and the Impact of Nursing Home Report Cards. Health Services Research 2011;46(6):1698–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. RCS-I Model Calculation Worksheet for SNFs [Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/SNFPPS/Downloads/RCS_I_Logic-508_Final.pdf

- 17.Wysocki A, Thomas KS, Mor V. Functional Improvement Among Short-Stay Nursing Home Residents in the MDS 3.0. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2015; 16(6): 470–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare. Data by Region [Available from: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/region/.

- 19.Gronniger T, Fiedler M, Patel K, Adler K, Ginsburg PB. How Should The Trump Administration Handle Medicare’s New Bundled Payment Programs? In Health Affairs Blog 2017.