Abstract

Treadmill running and tibial loading are two common modalities used to assess the role of mechanical stimulation on the skeleton preclinically. The primary advantage of treadmill running is its physiological relevance. However, the applied load is complex and multiaxial, with observed results influenced by cardiovascular and musculoskeletal effects. In contrast, with tibial loading, a direct uniaxial load is applied to a single bone, providing the advantage of greater control but with less physiological relevance. Despite the importance and wide-spread use of both modalities, direct comparisons are lacking. In this study, we compared effects of targeted tibial loading, treadmill running, and their combination on cancellous and cortical architecture in a murine model. We show that tibial loading and treadmill running differentially improve bone mass, with tibial loading resulting in thicker trabeculae and increased cortical mass, and exercise resulting in greater number of trabeculae and no cortical mass-based effects. Combination of the modalities resulted in an additive response. These data suggest that tibial loading and exercise may improve mass differentially.

Keywords: Exercise, Tibia, Mechanical, CT, Trabecular, Cortical

Highlights

-

•

Tibial loading increased trabecular thickness while exercise increased number.

-

•

Combined effects of loading and exercise were additive in cancellous bone.

-

•

In cortical bone, loading increased cross-sectional area.

-

•

No mass-based effects were noted due to exercise.

1. Introduction

Bone is a dynamic structure that can alter its mass and architecture to accommodate a changing environment. Increases in load result in increased bone mass, and conversely, decreases in load result in decreased bone mass. This theory of bone adaption, referred to as mechanostat, has been well-established in both clinical (Wolman et al., 1991; Warden et al., 2014) and preclinical (Turner, 1998) studies. Within the preclinical realm, studies can often be broadly separated into two groups: 1) exercise-based and 2) external mechanical stimulation.

For exercise studies, animals undergo some form of physical activity, such as running (Iwamoto et al., 1999; Wallace et al., 2007; Wallace et al., 2009), jumping (Umemura et al., 1997; Ju et al., 2008), or swimming (Swissa-Sivan et al., 1990; Hart et al., 2001), causing stimulation of the bone and thereby inducing a bone formation response. The primary advantage of these models is their physiological relevance and translatability. However, this is also the primary disadvantage in that systemic effects are difficult, if not impossible, to fully account for. Loads are multiaxial, and the observed results are influenced by cardiovascular and muscular effects, in addition to the applied mechanical strains engendered on bone. In general, most running studies have shown positive influence on cancellous bone mass and cortical mechanical integrity, though these results are heavily influenced by sex (Wallace et al., 2007), age (Gardinier et al., 2018), and analysis location (Iwamoto et al., 1999). While these studies are important, the lack of control over the loading profile has made it difficult to assess the effect of specific alterations to loading stimulus or to target specific mechanotransduction pathways.

More recently, external mechanical stimulation protocols have been developed, providing researchers with the advantage of greater control but with less physiological relevance. These protocols apply a direct, predominately uniaxial, load to a single bone or limb, enabling control over the precise stimulus delivered to the bone (Turner et al., 1991; Lee et al., 2002; De Souza et al., 2005). Although a variety of external mechanical stimulation protocols have been utilized, one increasingly popular method is tibial loading, in which the tibia of an anesthetized rodent is placed within a mechanical test device and non-invasively loaded with a cyclic waveform (De Souza et al., 2005). The increased control in these models has enabled researchers to explore types of loads that are anabolic. For example, bone formation is both strain (Sugiyama et al., 2012) and strain rate (Turner et al., 1995, Mosley and Lanyon, 1998) dependent. Mechanistic studies have also been conducted, with targeted loading used to tease out the role of various molecules in mechanotrasduction pathways (Saxon et al., 2011; Morse et al., 2014). Despite these advantages, the physiological relevance of this model is less clearly defined.

While both types of models engender strain stimulus on bone and induce a bone formation response, previous data in our lab has suggested that exercise and tibial loading may differentially improve bone mass; however, few studies have assessed this question. Results drawn from one type are often used to interpret findings from a different type of loading. The primary goal of this study was to explicitly show some of these differences. Moreover, if mechanisms of bone formation are different, it would imply that the combined effects of exercise and tibial loading should increase bone's response in an additive manner. To test this hypothesis, we compared effects of targeted tibial loading, treadmill running, and their combination on cancellous and cortical architecture in a murine model.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental overview

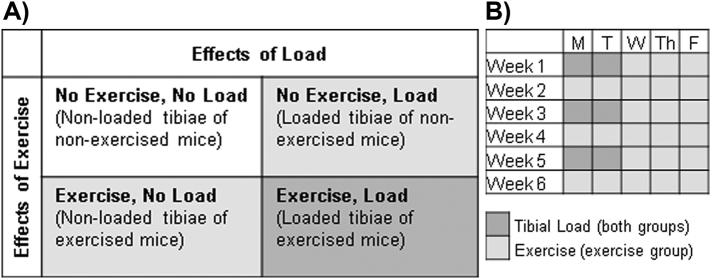

All procedures were performed with prior approval from the Indiana University School of Science Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Male C57Bl/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and separated into two groups: exercise (EX; n = 12) and sedentary control (SED; n = 12). All mice were housed individually to prevent cage fighting which may mask effects of loading (Meakin et al., 2013), but we did not measure the background loading between groups. Beginning at 8 weeks of age, both exercise and sedentary mice underwent compressive loading of the right tibia (details below) for two consecutive days every other week (i.e. Mon/Tues of weeks 1, 3, and 5). The contralateral limb was used as an internal non-loaded control (Sugiyama et al., 2010). On the remaining days of each week and on the alternating weeks, the exercise mice ran on a treadmill (details below). At 14 weeks of age, mice were euthanized and their tibiae stored wrapped in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-soaked gauze at −20 °C. This study design resulted in four groups (n = 12/group): 1) no exercise and non-loaded, 2) no exercise and loaded, 3) exercise and non-loaded, and 4) exercise and loaded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental overview showing A) groups and B) loading and exercise schedule.

2.2. In vivo tibial loading

Mice were anesthetized (2% Isoflurane) and their right limb cyclically loaded in compression. Each loading profile consisted of 2 cycles at 4 Hz to 11.9 N, followed by a 1-second rest at 2 N, repeated 110 times for a total of 220 compressive cycles per day. This profile differs from that previously reported from our group (Berman et al., 2015) due to the observation of limping in later cohorts of mice (data unpublished). We found that increasing the frequency to 4 Hz and holding the load at 2 N during the rest period reduced limping. In the current study, limping was not observed. Moreover, the load level is within the range of loads shown to induce a bone formation response (De Souza et al., 2005; Sugiyama et al., 2012; Berman et al., 2015). Note that although we did not perform histology, we did not observe any signs of woven bone from micro-computed tomography (micro-CT).

2.3. Treadmill running

On exercise days, the exercise group ran on a treadmill (Animal Treadmill: Exer 3/6; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA) at a 5° incline for 30 min. Over the first few days of exercise, mice were acclimated to the treadmill, beginning at a rate of 6 m/min and slowly building up to 12 m/min. By the second week, all mice maintained a 12 m/min rate for the duration of the running bout.

2.4. Computed tomography (CT)

Harvested tibiae were scanned by high resolution micro-CT (Skyscan 1172; Bruker, Kontich, Belgium) using the following parameters: 10 μm resolution, 60 kV tube voltage, 167 μA current, 0.7-degree increment angle, and 2-frame averaging. To convert gray-scale images to mineral content, hydroxyapatite calibration phantoms (0.25 and 0.75 g/cm3 CaHA) were also scanned. After reconstruction and rotation using Bruker software (nRecon and DataViewer), regions of interest were selected in the proximal metaphysis, proximal-mid diaphysis, and mid-diaphysis for analysis.

The proximal metaphysis was selected as a 2-mm region of interest, beginning at the distal end of the proximal growth plate and extending distally. Cancellous bone was then automatically segmented from its surrounding cortical shell in CTAn (Bruker) and manually checked for accuracy of segmentation. The region of interest was then analyzed in CTAn to determine bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), number (Tb.N), separation (Tb.Sp), bone mineral density (BMD), and tissue mineral density (TMD).

For the proximal-mid and mid-diaphysis locations, a 1-mm region of interest was selected at 37% and 50% of the bone length, respectively, measured from the top of the bone. The cortical shaft was analyzed (Matlab, MathWorks, Inc. Natick, MA) to determine areas (total cross sectional area [Tt.Ar], cortical area [Ct.Ar], and marrow area [Ma.Ar]), cortical thickness (Ct.Th), cortical area fraction (Ct.Ar/Tt.Ar), perimeters (periosteal [Ps.Pm] and endocortical [Ec.Pm]), principal moments of inertia (Imax and Imin), and tissue mineral density (TMD).

2.5. Statistics

Main effects of exercise and tibial loading were assessed in Prism (v7.03, Graphpad) by repeated measures two-way ANOVA to assess the main effects of loading (within-subject effect), exercise (between-subject effect), and their interaction (p < 0.05). No significant interaction terms were noted for these data and, therefore, no post hoc analyses were performed. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Body weight and tibial length

At the beginning of the study, mice were weight-matched into sedentary (23.15 ± 1.56 g) and exercise (23.17 ± 1.56 g) groups. At the end of the study, body weights remained statistically indistinguishable (SED: 26.6 ± 1.4 g, EX: 26.0 ± 1.0 g; p = ns). In contrast, tibial length, as measured with calipers at the end of the study, was significantly increased due to loading (p = 0.02) but not exercise. Despite its significance, differences in tibial length were modest (SED Non-Loaded: 18.2 ± 0.6 mm, SED Loaded: 18.3 ± 0.5 mm, EX Non-Loaded: 17.9 ± 0.3, EX Loaded: 18.2 ± 0.4 mm).

3.2. Tibial loading and exercise differentially improve cancellous bone mass

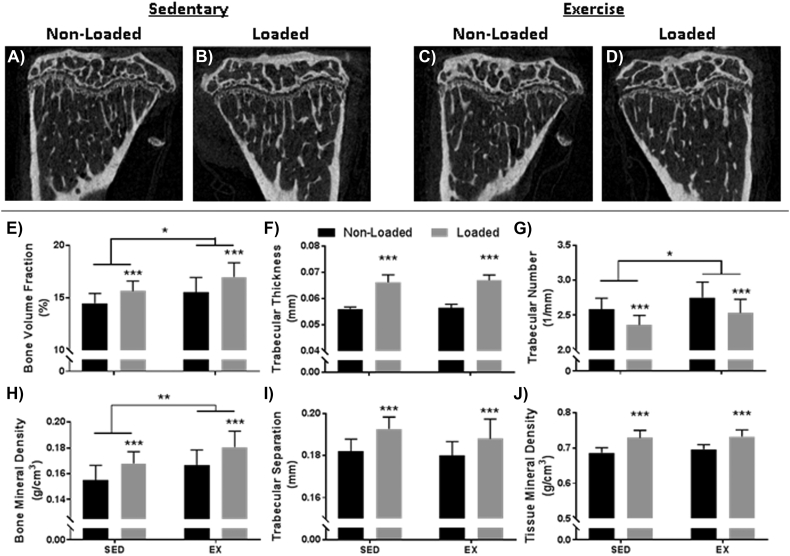

A 2-mm metaphyseal region of interest was analyzed to assess cancellous bone properties (Fig. 2). Results indicated that tibial loading (+7.9%; p = 0.01) and exercise (+7.2%; p < 0.001) similarly improved bone volume fraction (BV/TV) compared to the non-loaded sedentary bones. Combined effects of the two modalities were additive, showing a 17.2% improvement in bone volume fraction. Similar results were also observed for bone mineral density (BMD), with tibial loading resulting in an 8.3% improvement (p < 0.001), exercise resulting in a 7.3% improvement (p < 0.01), and their combined effect additive (+16.5%).

Fig. 2.

Cancellous properties within the tibial metaphysis are shown qualitatively (A–D) and quantitatively (E–J). Results indicate improved bone volume fraction (E) and bone mineral density (H) due to both tibial loading and exercise. Combined effects were additive. Tibial loading predominately improved trabecular thickness (F) with detrimental impacts to trabecular separation (I), while exercise predominately improved trabecular number (G). Only tibial loading improved tissue mineral density (J). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Despite similar increases in bone volume fraction and bone mineral density for tibial loading and exercise, the mechanism by which mass was increased varied for the two modalities. Tibial loading primarily improved trabecular thickness (+18.3%; p < 0.001) with detrimental impacts to trabecular number (−8.7%; p < 0.001) and separation (+5.8%; p < 0.001). In contrast, exercise predominately improved bone mass through greater trabecular number (+6.4%; p < 0.05) with modest non-significant changes in trabecular separation and thickness. In combination, additive effects were noted for all three properties (+19.6% for thickness, +3.2% for separation, and −2.0% for number).

Interestingly, although both modalities improved bone mass, only tibial loading significantly impacted tissue mineral density (+6.2%; p < 0.001). Exercise modestly improved the value (+1.5%), but results were non-significant.

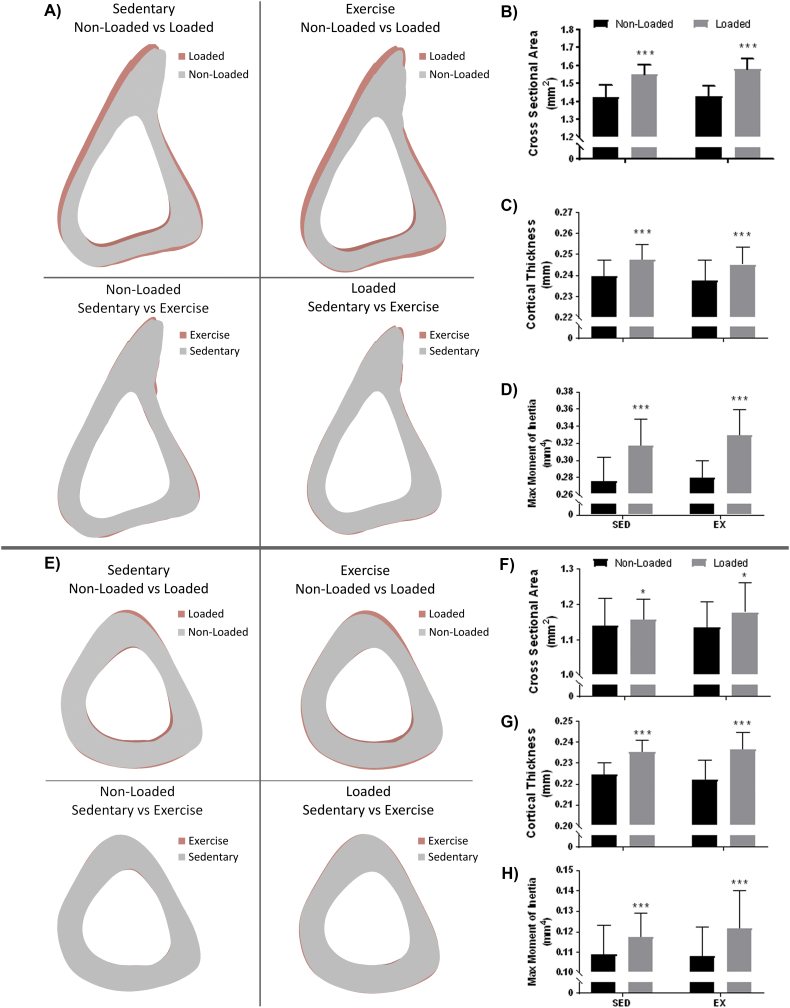

3.3. Tibial loading, but not exercise, improves cortical bone mass

In contrast to the cancellous region, only tibial loading improved bone mass in the cortical proximal-mid and mid-diaphysis locations. At the proximal-mid location, loading resulted in both periosteal and endocortical expansion, with the loaded bones having a thicker cortex than their non-loaded controls. Similarly, at the mid-diaphysis, loading also resulted in periosteal expansion, as noted by a significantly greater cross-sectional area. Marrow area and endosteal bone surface were reduced, suggesting endocortical contraction at this location. With the exception of periosteal bone surface at the mid-diaphysis location, all structural parameters measured at both the proximal-mid and mid-diaphysis were significantly altered due to loading whereas no properties were significantly changed due to exercise (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Similar to the cancellous region, the proximal-mid location showed increased tissue mineral density with loading. Interestingly, unlike the cancellous and mid-proximal regions, tissue mineral density at the mid-diaphysis was not significantly improved due to loading.

Fig. 3.

Cortical analysis at the proximal-mid (A–D) and mid (E–H) locations indicated a strong bone formation response due to loading (A and E, top panels) but not exercise (A and E, bottom panels). These effects can be observed quantitatively through significantly improved cross sectional area (B, F), cortical thickness (C, G), and maximum moment of inertia (D, H) in the loaded limb. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Quantified cortical parameters from proximal-mid and mid locations indicate improved bone mass due to loading but not exercise. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

| Sedentary |

Exercise |

Two-way ANOVA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-loaded | Loaded | Non-loaded | Loaded | Exercise | Load | Interaction | |

| Proximal-mid location (37%) | |||||||

| Cross sectional area (mm2) | 1.421 (0.072) | 1.551 (0.052) | 1.428 (0.059) | 1.581 (0.058) | ns | *** | ns |

| Cortical area (mm2) | 0.839 (0.031) | 0.917 (0.029) | 0.836 (0.033) | 0.921 (0.031) | ns | *** | ns |

| Marrow area (mm2) | 0.582 (0.050) | 0.635 (0.039) | 0.592 (0.043) | 0.660 (0.045) | ns | *** | ns |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.240 (0.008) | 0.247 (0.007) | 0.237 (0.010) | 0.245 (0.009) | ns | *** | ns |

| Periosteal bone surface (mm) | 6.067 (0.171) | 6.164 (0.150) | 6.132 (0.173) | 6.221 (0.184) | ns | * | ns |

| Endosteal bone surface (mm) | 3.679 (0.149) | 3.816 (0.125) | 3.700 (0.132) | 3.892 (0.150) | ns | *** | ns |

| Max moment of inertia (mm4) | 0.275 (0.028) | 0.317 (0.031) | 0.279 (0.020) | 0.329 (0.031) | ns | *** | ns |

| Min moment of inertia (mm4) | 0.092 (0.012) | 0.109 (0.010) | 0.093 (0.012) | 0.112 (0.010) | ns | *** | ns |

| Tissue mineral density (g/cm3) | 0.780 (0.015) | 0.788 (0.012) | 0.777 (0.020) | 0.783 (0.019) | ns | ** | ns |

| Mid location (50%) | |||||||

| Cross sectional area (mm2) | 1.139 (0.077) | 1.155 (0.061) | 1.134 (0.074) | 1.176 (0.085) | ns | * | ns |

| Cortical area (mm2) | 0.693 (0.038) | 0.727 (0.030) | 0.686 (0.038) | 0.738 (0.038) | ns | *** | ns |

| Marrow area (mm2) | 0.445 (0.043) | 0.428 (0.035) | 0.448 (0.049) | 0.439 (0.056) | ns | * | ns |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.224 (0.006) | 0.235 (0.006) | 0.222 (0.009) | 0.236 (0.008) | ns | *** | ns |

| Periosteal bone surface (mm) | 4.608 (0.144) | 4.639 (0.129) | 4.593 (0.144) | 4.664 (0.171) | ns | ns | ns |

| Endosteal bone surface (mm) | 3.007 (0.159) | 2.937 (0.124) | 3.001 (0.174) | 2.956 (0.195) | ns | * | ns |

| Max moment of inertia (mm4) | 0.109 (0.014) | 0.117 (0.012) | 0.108 (0.014) | 0.122 (0.019) | ns | *** | ns |

| Min moment of inertia (mm4) | 0.075 (0.010) | 0.077 (0.008) | 0.074 (0.008) | 0.080 (0.009) | ns | ** | ns |

| Tissue mineral density (g/cm3) | 0.891 (0.017) | 0.886 (0.013) | 0.883 (0.017) | 0.885 (0.021) | ns | ns | ns |

4. Discussion

Tibial loading and exercise are two common modalities used to assess the effects of mechanical stimulation on the skeleton. However, direct comparisons of the two modalities are lacking. In this study, we show that tibial loading and treadmill running differentially improve bone mass, with tibial loading resulting in thicker trabeculae and increased cortical mass, and treadmill running resulting in greater number of trabeculae and no cortical mass-based effects.

To the authors' knowledge, only one paper to date has utilized both exercise and tibial loading; however, their exercise protocol was mild (3 days/week for 2 weeks) with the aim of supplementing the tibial loading rather than comparing it with tibial loading (Meakin et al., 2015). In addition, they used female mice at 16 weeks of age, compared to our 8 week old male mice. As a result, although the mass-based effects of their tibial loading were similar to our study (e.g. increased bone volume fraction and cortical cross-sectional area), the exercise portion of their results showed no effects, making it difficult to compare the structural changes driven by treadmill running and tibial loading. In contrast, we exercised mice 3–5 times per week for 6 weeks in order to induce an osteogenic response, enabling us to directly compare bone formation due to both exercise and tibial loading.

The tibial loading profile used in this study was similar to profiles reported previously (cyclic, rest-inserted loading) (De Souza et al., 2005; Lynch et al., 2010; Willie et al., 2013), though the presence of rest between cycles has recently been suggested to be unnecessary (Yang et al., 2017). The load, 11.9 N, is within the range of common load levels that have been shown to increase bone volume fraction (De Souza et al., 2005; Lynch et al., 2011; Sugiyama et al., 2012; Berman et al., 2015). Interestingly, despite the plethora of papers utilizing tibial loading, a rarely discussed point is the observation that the increase in cancellous bone mass due to tibial loading is often predominately driven by increases in trabecular thickness rather than trabecular number and spacing (Lynch et al., 2011; Holguin et al., 2013; Weatherholt et al., 2013; Willie et al., 2013; Berman et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017), though this is not always the case (Lynch et al., 2010; Sugiyama et al., 2010). The current study showed similar results, with a 7.9% increase in bone volume fraction due to an 18.3% increase in trabecular thickness, while the number of trabeculae was significantly decreased. In contrast to tibial loading, the exercise increased bone volume fraction and BMD primarily by increasing trabecular number, suggesting a different mechanism. Based on these results, although tibial loading still can and does provide a wealth of information regarding mechanotransduction, care must be taken in translating observed results due to tibial loading to expected results due to treadmill running.

One potential reason for these observed effects may be differences in strain (both magnitude and direction) between tibial loading and exercise. Previous studies have shown that low load levels during tibial loading are insufficient to induce a bone formation response (De Souza et al., 2005; Sugiyama et al., 2012; Berman et al., 2015). For that reason, we chose a higher load value that was within the range of loads shown to induce a formation response. However, by doing so, we also presumably selected a strain level that was much higher than is typically observed during treadmill running. For example, in 12 week old mice, walking was found to engender approximately 200 μɛ of tension, but in the same study, the authors found that approximately 1500 μɛ (i.e. 10 N) was required to engender a bone formation response during tibial loading (De Souza et al., 2005). Thus, the 11.9 N load that we used in the current study likely engenders much higher strain than treadmill running.

Another important difference to note is that, during tibial loading, the loading direction is more uniform. Although the natural curvature of the tibia causes eccentric loading (i.e. bending) that leads to regions of compression and tension (Yang et al., 2014), the load is still applied in a more uniform, predominately uniaxial, direction without the influence of off-axis muscle and ground reaction forces. This may enable increased alignment of bone formation, causing greater trabecular thickness. Given these differences, it is unlikely that there would be a perfect profile that would mimic the response observed due to exercise.

Within the cortex, differences in bone formation were also noted, with tibial loading causing improved cortical area and exercise having no mass-based effect. Both results are similar to those observed previously (Kohn et al., 2009; Berman et al., 2015; Hammond et al., 2016). However, it should be noted that this study only explored microstructural mass-based changes, and did not assess histology or quality-based changes to the tissue. Thus, the lack of bone mass response observed in the exercised mice does not imply that the matrix is unaffected. Previous work has demonstrated that treadmill running (both with and without changes in mass) can improve aspects of bone quality, predominately the collagen components (Wallace et al., 2007, Kohn et al., 2009, Wallace et al., 2009, Hammond and Wallace, 2015). Recent work has corroborated that these changes in tissue quality can have positive effects on mechanical properties associated with bone ductility (Gardinier et al., 2018) and toughness (Hammond et al., 2016). Similarly, tissue-level changes have been observed due to tibial loading, with short-term loading altering the mineralization of the matrix in both an age-dependent (Aido et al., 2015) and bone site-specific manner (Bergstrom et al., 2017), leading to improvements in tissue-level mechanics (Berman et al., 2015).

In summary, we have shown that, in the cancellous region, tibial loading led to greater trabecular thickness while exercise led to greater number. Both improved bone volume fraction, with their combined effects resulting in an additive bone mass response. In the cortical region, only tibial loading resulted in increased bone mass, though that does not preclude the presence of non-mass based effects. These data suggest that tibial loading and exercise may improve mass differentially.

Transparency document

Transparency document

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Michael Frye and Alexis Lewandowski for their help with the in vivo exercise and loading portion. This work was supported by the NIH (AR067221 to J.M.W.) and the NSF (DGE-1333468 to A.G.B.).

Declarations of interest

None.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

References

- Aido M. Effect of in vivo loading on bone composition varies with animal age. Exp. Gerontol. 2015;63:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom I. Compressive loading of the murine tibia reveals site-specific micro-scale differences in adaptation and maturation rates of bone. Osteoporos. Int. 2017;28(3):1121–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3846-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A.G. Structural and mechanical improvements to bone are strain dependent with axial compression of the tibia in female C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza R.L. Non-invasive axial loading of mouse tibiae increases cortical bone formation and modifies trabecular organization: a new model to study cortical and cancellous compartments in a single loaded element. Bone. 2005;37(6):810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardinier J.D. Bone adaptation in response to treadmill exercise in young and adult mice. Bone Rep. 2018;8:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond M.A., Wallace J.M. Exercise prevents [beta]-aminopropionitrile-induced morphological changes to type I collagen in murine bone. BoneKEy Rep. 2015;4 doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond M.A. Treadmill exercise improves fracture toughness and indentation modulus without altering the nanoscale morphology of collagen in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart K.J. Swim-trained rats have greater bone mass, density, strength, and dynamics. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91(4):1663–1668. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holguin N. Adaptation of tibial structure and strength to axial compression depends on loading-history in both C57BL/6 and BALB/C mice. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013;93(3):211–221. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto J. Differential effect of treadmill exercise on three cancellous bone sites in the young growing rat. Bone. 1999;24(3):163–169. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Y.-I. Jump exercise during remobilization restores integrity of the trabecular architecture after tail suspension in young rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104(6):1594–1600. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01004.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn D.H. Exercise alters mineral and matrix composition in the absence of adding new bone. Cells Tissues Organs. 2009;189(1–4):33–37. doi: 10.1159/000151452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.C. Validation of a technique for studying functional adaptation of the mouse ulna in response to mechanical loading. Bone. 2002;31(3):407–412. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00842-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M.E. Cancellous bone adaptation to tibial compression is not sex dependent in growing mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;109(3):685–691. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00210.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M.E. Tibial compression is anabolic in the adult mouse skeleton despite reduced responsiveness with aging. Bone. 2011;49(3):439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meakin L.B. Male mice housed in groups engage in frequent fighting and show a lower response to additional bone loading than females or individually housed males that do not fight. Bone. 2013;54(1):113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meakin L.B. Exercise does not enhance aged bone's impaired response to artificial loading in C57Bl/6 mice. Bone. 2015;81:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse A. Mechanical load increases in bone formation via a sclerostin-independent pathway. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29(11):2456–2467. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley J.R., Lanyon L.E. Strain rate as a controlling influence on adaptive modeling in response to dynamic loading of the ulna in growing male rats. Bone. 1998;23(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon L.K. Analysis of multiple bone responses to graded strains above functional levels, and to disuse, in mice in vivo show that the human Lrp5 G171V high bone mass mutation increases the osteogenic response to loading but that lack of Lrp5 activity reduces it. Bone. 2011;49(2):184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.03.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T. Functional adaptation to mechanical loading in both cortical and cancellous bone is controlled locally and is confined to the loaded bones. Bone. 2010;46(2):314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T. Bones' adaptive response to mechanical loading is essentially linear between the low strains associated with disuse and the high strains associated with the lamellar/woven bone transition. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27(8):1784–1793. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swissa-Sivan A. The effect of swimming on bone modeling and composition in young adult rats. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1990;47(3):173–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02555984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Bone. 1998;23(5):399–407. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C.H. A noninvasive, in vivo model for studying strain adaptive bone modeling. Bone. 1991;12(2):73–79. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(91)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C.H. Mechanotransduction in bone: role of strain rate. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;269(3):E438–E442. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.3.E438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura Y. Five jumps per day increase bone mass and breaking force in rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997;12(9):1480–1485. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J.M. Exercise-induced changes in the cortical bone of growing mice are bone- and gender-specific. Bone. 2007;40(4):1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J.M. Short-term exercise in mice increases tibial post-yield mechanical properties while two weeks of latency following exercise increases tissue-level strength. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2009;84(4):297–304. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden S.J. Physical activity when young provides lifelong benefits to cortical bone size and strength in men. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111(14):5337–5342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321605111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherholt A.M. Cortical and trabecular bone adaptation to incremental load magnitudes using the mouse tibial axial compression loading model. Bone. 2013;52(1):372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie B.M. Diminished response to in vivo mechanical loading in trabecular and not cortical bone in adulthood of female C57Bl/6 mice coincides with a reduction in deformation to load. Bone. 2013;55(2):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolman R.L. Different training patterns and bone mineral density of the femoral shaft in elite, female athletes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1991;50(7):487–489. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.7.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Characterization of cancellous and cortical bone strain in the in vivo mouse tibial loading model using microCT-based finite element analysis. Bone. 2014;66:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Effects of loading duration and short rest insertion on cancellous and cortical bone adaptation in the mouse tibia. PLoS One. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document