Abstract

Annette Prüss-Ustün and colleagues consider the role of air pollution and other environmental risks in non-communicable diseases and actions to reduce them

Environmental risk factors are recognised as an important cause of disease burden, but the impact on non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is now being established.1 2 3 Household and outdoor air pollution, alongside unhealthy diets, lifestyles, and work environments, were recently included in the global strategy to prevent NCDs.4 5

In this context, environmental risks to health are defined as all the external physical, chemical, biological, and work related factors that affect a person’s health, excluding factors in natural environments that cannot reasonably be modified. Environmental risks to health include pollution, radiation, noise, land use patterns, work environment, and climate change.

These risks are driven by policies in sectors outside the health sector, such as energy, industry, agriculture, transport, and land planning. More cooperation is needed if the health sector is to effectively tackle NCDs and reduce health costs resulting from policies in other sectors. Here, we summarise the evidence for the links between environmental risks and NCDs, review existing solutions and interventions, and outline opportunities for reducing environmental risks as part of an intersectoral NCD agenda.

Contribution of environmental risks to non-communicable diseases

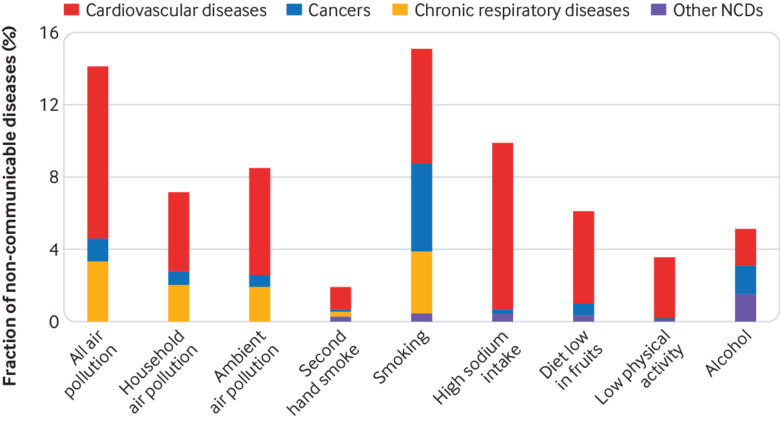

In 2016 air pollution was the second largest risk factor causing NCDs globally, just after tobacco smoking (fig 1). In many countries—for example, in southeast Asia—air pollution is by far the largest cause of NCDs.

Fig 1.

Attributable fraction of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) for selected risk factors by disease group, 2016.6 7 *Ambient and household air pollution as characterised by indicator of particulate matter. For air pollution, alternative sources provide similar results: 13%6 and 10%8 instead of 14% of NCDs

Air pollution alone caused 5.6 million deaths from NCDs in 2016.7 Ninety one per cent of people worldwide are exposed to harmful pollution levels in ambient air,9 and almost all countries are affected. More than 40% of people, mainly in low and middle income countries, are cooking with inefficient technology and fuel combinations, generating harmful smoke in their homes. Together, 24% of cases of stroke, 25% of ischaemic heart disease, 28% of lung cancer, and 43% of chronic obstructive respiratory disease are attributable to ambient and household air pollution, and evidence on additional NCDs is emerging.1

Risks related to selected chemicals and chemical mixtures, in the home, community, or workplace, have caused 1.3 million deaths from NCDs in 2016, mainly from cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancers. Neurological and mental disorders are also associated with chemicals.10 Exposure to lead in paints, consumer products, air, and water caused 540 000 deaths from cardiovascular and kidney disease in 2016,6 Occupational carcinogens and airborne exposures caused 882 000 NCD deaths in 2016,11 while exposure to residential radon caused 58 000 lung cancer deaths.6 The health effects of many environmental risks have probably not yet been assessed.12

Much of the global change in NCDs has been driven by population growth and ageing in the past decade,13 increasing the population vulnerable to NCD determinants. The risks causing the most rapidly rising NCD deaths globally between 2010 and 2016 are ambient air pollution with a 9% increase and low physical activity with an 11% increase.6 Low physical activity has an environmental component, through transport modes, city design, and access to green spaces.14 15 16 NCD deaths from household air pollution, on the other hand, have reduced, but progress needs to be accelerated to reach the sustainable development goal.13 17

NCDs are further exacerbated by climate change, which has already started to amplify cardiovascular and respiratory mortality during more frequent heat episodes. Without more action, people will increasingly be affected by environmental risks to health.

Existing solutions and interventions

Many practical solutions and tools are readily available to curb pollution and create healthier environments. Efficient strategies often require action in sectors beyond the health sector, in areas such as reduction of air pollution, the safe use of chemicals, protection from radiation, occupational safety and health measures, and workplace wellness (see web appendix on bmj.com).

Creating healthier environments for reducing NCDs also results in many health and non-health co-benefits. Many policies combatting air pollution also mitigate climate change.18 Replacement of polluting cooking stoves with cleaner energy solutions and better energy efficiency of homes and buildings leads to cleaner air and limits climate change. For transport, less polluting vehicles, combined rapid transit with walking and cycling, and replacement of short urban motorised journeys by walking and cycling would increase physical activity and improve access to jobs. In agriculture, banning open burning both reduces air pollution and mitigates climate change; lower red meat consumption reduces NCDs directly and mitigates climate change through reduced gas emissions from livestock.18 Reducing air pollution from coal fired power plants may not only diminish health risks due to combustion particles but also prevent mercury from entering the food chain. Such co-benefits need to be accounted for in economic evaluations of environmental health action.

Acting on environmental risks can reduce health inequity, as women and the poor are disproportionally affected. Women and children are more exposed to harmful smoke caused by cooking, heating, and lighting with unclean fuels and inefficient technologies. Environmental risks to health can to some extent be influenced through personal choices (vegan diet, transport choice) but are likely to be more affected by policy measures (incentivising clean technologies, carbon and fuel taxation) necessary to deliver on the Paris Agreement on climate change. Implementing wide ranging policy changes may be more equitable than acting on individual behaviour.

Intersectoral opportunities to reduce environmental risks

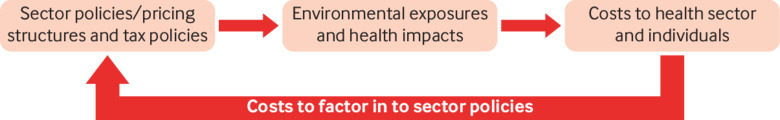

Despite certain successes, the overall burden of disease caused by the environment has not decreased. In addition to the practical solutions, more organisational and structural measures are needed. Given that decisions leading to healthier environments often lie outside the health sector, the health argument needs to be integrated at the level of these “upstream” decisions (choices made at the level of policy setting).19 Failing to do so, by selecting options that may be economically sound for the particular sector but may not be healthy, will merely result in transferring costs to the health sector and society at large (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Cost transfer from various sector policies to the health sector and individuals

About 10% of the global gross domestic product is spent on healthcare, but little is allocated to primary prevention.20 Conventional healthcare systems alone can no longer sustainably tackle the burden of NCDs. Fiscal policies reflecting the true costs of sectoral policies, designed without compromising social and equity aspects, could avoid such transfers and free funds for prevention. A recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund shows that fuel prices around the world de facto “subsidise” polluting fuels with more than $5tn (£3.9tn; €4.4tn) annually, as damage to health and climate has not been taken into account.21

The human and financial costs of the environment and NCDs mean that the NCD agenda needs to strategically influence the drivers of pollution and further environmental risks in other sectors. The involvement of the health sector is also important in tracking health determinants and outcomes, proposing effective, evidence based solutions, and predicting health impacts of policies and projects through appropriate tools. A transformation on how health shapes sectoral and societal choices is needed to achieve a major change. Ingredients for such a transformation include the actions in box 1, which are part of WHO’s global strategy on health, environment, and climate change.22 25

Box 1. Actions needed to transform how health shapes sectoral and societal choices.

Scale up prevention through healthier environments

A shift of resources is needed to reduce the main environmental risks of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and fully integrate pollution control, healthy urban design, and sustainable transport into national NCD strategies. Taxes and pricing structures in all relevant sectors need to be strategically influenced to reflect the full prices of strategies and resources allocated commensurate to the damages caused

Drive policies in other sectors through the health argument

Large transitions—for example, in energy and transport—are progressing in many countries. Labour policies and economic development are determining workers’ health and safety, and land use planning is shaping cities, their walkability, their green spaces, and their zoning as they expand. Health needs to play a determining role in decision making and promote inclusive public participation in other sectors with policies influencing health to control NCDs effectively. Frameworks for action, such as “health in all policies” or “whole of government” approaches are useful in such processes23 24

Engage the health sector in a leadership and coordinating role in all health related matters

To assume its new or scaled up functions, the health sector may need to acquire additional competencies and capacities and be supported by new governance mechanisms allowing it to assume this role. This may require decisions and mechanisms at the highest level—that is, above those of sectors, setting overall policy directions, and assigning roles across sectors

Enhance evidence based communication and advocacy

Evidence based guidance and information about risks and benefits of environmental conditions to the public and policy makers are essential to spur rational decision making, to create a demand for healthier environments, and to foster community engagement. The health sector, including health professionals, healthcare organisations, medical societies, and non-governmental organisations, can play an important role by engaging in such communication

With the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, the world is calling for a new approach to health, environment, and equity, generating high level political support for tackling health determinants in a preventive and sustainable way. Together with the increasing NCD epidemic and its high costs to society, a unique opportunity exists for changing the way the global health community, policy makers, and society at large engage and shift focus towards prevention of disease through healthier environments.

Conclusion

The past few decades have seen a global epidemiological transition from communicable diseases to NCDs, with major causes being pollution and other environmental risks. NCDs cannot be sustainably controlled without the global health community being actively engaged in the shaping of environmental drivers of health, taking up new leadership and coordination activities across all relevant sectors. Interventions to reduce environmental risks to health may have multiple co-benefits, such as increasing social equity, mitigation of climate change, and increasing energy efficiency.

Key messages.

Air pollution is the second leading cause of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) globally, and other environmental risks are important contributors

The health sector needs to actively engage and participate in the development of policies in other sectors where many environmental risks to health are shaped, such as energy or transport policies

Creating healthier environments should be mainstreamed into policies for reducing NCDs

This will yield multiple co-benefits for health, social welfare, social equity, and the environment

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Table giving examples of interventions to reduce environmental risks

For other articles in the series see www.bmj.com/NCD-solutions

Contributors and sources: Information sources include a review of the effects on NCDs of environmental risk factors and the draft WHO strategy on health, environment, and climate change. APU conceived the outline of the paper and drafted the first version. MN is the director of the department and provided overall guidance. All authors contributed intellectual content, provided specific inputs on their area of expertise, edited the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series proposed by the WHO Global Coordination Mechanism on NCDs and commissioned by The BMJ, which peer reviewed, edited, and made the decisions to publish. Open access fees are funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA), UNOPS Defeat-NCD Partnership, Government of the Russian Federation, and WHO.

This article has been updated to provide full details on open access funding.

.

References

- 1. Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018;391:462-512. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32345-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neira M, Prüss-Ustün A, Mudu P. Reduce air pollution to beat NCDs: from recognition to action. Lancet 2018;392:1178-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32391-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Preventing noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) by reducing environmental risk factors. WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations. Political declaration of the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Time to deliver: accelerating our response to address non-communicable diseases for the health and well-being of present and future generations. 2018. https://ncdalliance.org/sites/default/files/Political_Declaration_final_text_0.pdf

- 5. World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange. 2018 [accessed 1 Oct 2018] http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

- 7.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory - Data repository. 2018. http://www.who.int/gho/database/en/.

- 8.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange Seattle: IHME. 2019 https://gbd2016.healthdata.org/gbd-search/.

- 9. World Health Organization Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health. Fact sheet. WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prüss-Ustün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Bos R, Neira M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolf J, Prüss-Ustün A, Ivanov I, et al. Preventing disease through a healthier and safer workplace. WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broadfoot M. Pollution is a global but solvable threat to health, say scientists: National Institute of environmental health science. 2019. https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2019/1/science-highlights/pollution/index.htm

- 13. GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1923-94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolch JR, Byrne J, Newell JP. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc Urban Plan 2014;125:234-44 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization Urban green spaces and health - a review of the evidence. WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kondo MC, Fluehr JM, McKeon T, Branas CC. Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:E445. 10.3390/ijerph15030445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. United Nations Policy brief #2: Achieving universal access to clean and modern cooking fules, technologies and services; Policy brief #10: Health and environment linkages - maximizing health benefits from the sustainable energy transition. Accelerating SDG7 achievement Policy briefs in support of the first SDG7 review at the UN high-level political forum 2018. United Nations, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell-Lendrum D, Prüss-Ustün A. Climate change, air pollution and noncommunicable diseases. 2018. https://www.who.int/bulletin/online_first/18-224295.pdf?ua=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19. Haaland C, van den Bosch CK. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban for Urban Green 2015;14:760-71 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Public spending on health and long-term care: a new set of projections. OECD, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coady D, Parry I, Sears L, Shang BP. How large are global fossil fuel subsidies? World Dev 2017;91:11-27 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization Health, environment and climate change. Report by the Director-General. EB142/12. WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization Health in all policies: training manual. WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Public Service Commission. The whole of government challenge. 2018. https://www.apsc.gov.au/1-whole-government-challenge.

- 25.World Health Organization. Draft WHO global strategy on health, environment and climate change. 2018. https://www.who.int/phe/publications/global-strategy/en/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Table giving examples of interventions to reduce environmental risks