Introduction

In economic theory, market competition is expected to enhance efficiency, improve quality, stimulate innovation and eventually control costs.1 Promoting competition with the aim of increasing efficiency and improving quality of healthcare systems has been the ‘mantra’ of the last three decades in developed countries, especially in Europe.2 Supporters claim that competition in healthcare, despite health market imperfections, can have beneficial effects, while its lack prevents managers from making their organisations efficient. Notably, public managers who are not accountable to owners/shareholders and have no bankruptcy constraint can keep on performing inefficiently with no risk of going out of business.3

Since decision-makers cannot rely on market prices to match demand and supply, political pressures are likely eventually to become the major ‘driver’ of their strategies. This is used to justify attempts to inject a ‘quasi market’ situation in a public sector.4 With tight regulation, this would reap the supposed efficiency gains of free markets without losing the equity benefits of traditional public systems.

The ‘forerunner’ reform in Europe consistent with this theory was the introduction in the early 1990s of the so-called ‘internal market’ in the British National Health Service5 – the most widely acknowledged public healthcare system in the world – by splitting health authorities into ‘purchasers’ and ‘providers’ to foster competition among the latter. This move towards a market-oriented system potentially including private providers has often been mentioned as an ‘Americanisation’ of the National Health Service,6 since the prevalence of private ‘players’ in the US makes this health system peculiar among most developed countries. The strategy has evolved into a process of privatisation by stealth – subcontracting out an increasing number of services in health. As highlighted by the collapse of Carillion,7 this has left the public core of the National Health Service increasingly isolated.

Subsequent experience in other western European countries has mainly focused on provider competition for hospital services,8 which account for the largest share of total healthcare expenditure in most countries9 and are based on the widespread adoption of fixed tariffs for funding admissions; as elsewhere in the world, these mainly came from the American experience of diagnosis-related groups.10

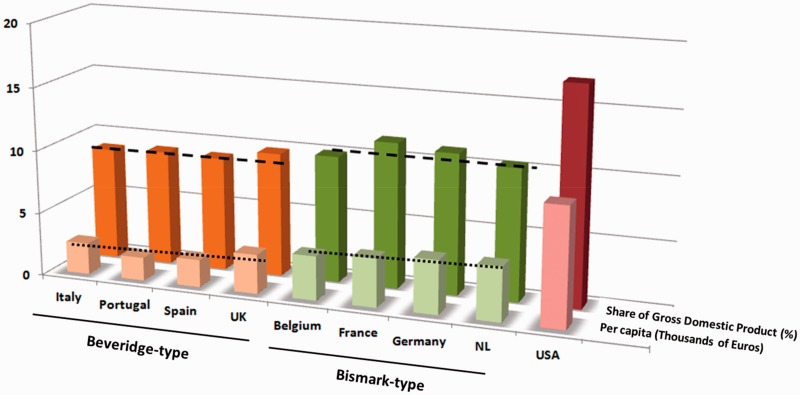

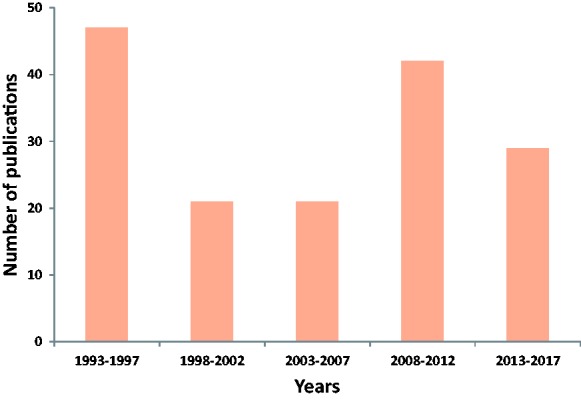

In the last decade, persisting economic austerity together with increases in the aging and multi-morbid population have put the health systems of even the wealthiest European countries under financial pressure,11 revamping the debate on the trade-off between competition and efficiency (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of studies conducted in European health care settings referring to competition in the title (1993-2017)*. *We searched the PubMed international database to select all articles including the key-words `competition' OR `market' AND `health' OR `healthcare' in their title. From the 272 studies conducted in European settings initially identified, 112 were not relevant to our scope, so we finally selected 160 articles.

Here, first we summarise the limits of competition theory in healthcare and then the major features of western European health systems. Finally, we look at the main critical issues of competition in healthcare and conclude with policy implications for the future in Europe.

Theoretical background

Healthcare can be considered a typical example of ‘market failure’ in economic theory from both the demand and supply sides. From the demand side, patients cannot be considered common consumers shopping around for their best deal,12 since they cannot be fully informed on health services, and illness makes them vulnerable, hence hardly rational and often open to ‘financial blackmail’ (especially for severe pathologies). The ‘information asymmetry’ gap of patients in medicine is filled by physicians, who establish a ‘principal-agent’ relationship with them on the micro level and respond to third-party payers for most healthcare prescribed on the macro level,13 making patients unaccountable for the costs of their illnesses. This lack of accountability for prescription expenses generates a potential ‘moral hazard’ for both physicians and patients.14

From the supply side, competition should require a reasonable number of providers offering the same service, operating in similar conditions, without any incentive to collude, and easy entry to and exit from markets.1 Limiting our remarks to hospital services, these conditions are rarely fulfilled, especially where hospitals are few, like in sparsely populated areas, or many hospitals are ‘neighbours’, like in urban areas.15 Especially in the latter, private hospitals are likely to concentrate on profitable services, while public hospitals are required to provide all the essential services, so they do not usually operate under similar conditions. This can induce opportunistic behaviour from private providers, such as specialising in the most profitable (‘cream-skimming’) or least costly (‘cherry-picking’) treatments to increase their revenue, declining treatments for costlier patients (‘dumping’) or discharging them earlier (‘skimping’) to minimise resource consumption.9,16

With these intrinsic limits, free prices in health markets can hardly reflect opportunity or marginal costs in the short or long run,5 by definition, and setting them through regulation is necessarily an arbitrary exercise,17 eventually resulting in distortion of relative prices and thus irrational allocation of financial resources.18

The European framework

Despite numerous sophisticated attempts to classify health systems in various groups according to several variables,19 a wise classification that is easy to adopt is still the historical one based on the extent of coverage, source of funding and ownership of provision,20 which leads to three ‘ideal’ types.

The National Health Service model (Beveridge-type), with universal coverage, mainly funding from general taxation, and mostly public provision.

The social health insurance model (Bismarck-type), with (almost) universal coverage, funding from mandatory social contributions, and public–private mix of provision.

The private health insurance model (American-type), mainly based on voluntary coverage, with main funding from private insurances, and mostly private provision.

According to the theoretical issues summarised above, the second and third types also need some public intervention to guarantee full healthcare services, especially to the poorest people. As a consequence, all modern health systems are subject to some degree of public regulation for funding and providing services,21 including the third type which, however, is applicable only in the US among developed countries.

The European National Health Services traditionally perform well in containing overall health expenditures (Figure 2), but with waiting times to access as their main weakness. Gate-keeping in primary care by general practitioners is considered crucial for cost containment in this type of system, mitigating specialists’ supply-induced demand for costly and often redundant procedures in secondary care,22 and when necessary privileging patients’ needs for rationed access to healthcare services.23 Although mostly remunerated publically, general practitioners are contractually the main ‘private’ component of most European National Health Services,4 being formally ‘small businessmen’.

Figure 2.

. Health Care Expenditure (2016). Source: https://stats.oecd.org/. Health expenditure and financing, 2016. Exchange rate (December 2016): 1GBP=1,1734EUR; 1USD=0,9487EUR.

Conversely, the ‘Achilles heel’ of social health insurances is containment of total health expenditure, offering more choice discretion to patients and shorter waiting lists, partially rationing healthcare through patients’ willingness and ability to (co)pay.23 Statutory sickness funds, though formally non-profit private bodies, are the main ‘hybrid’ component of European social health insurances,4 being regulated under public legislation.

Although recent reforms in these two types of healthcare services have aimed at limiting their weaknesses while keeping their strengths as well,11 somehow blurring their main features, European healthcare systems are still heterogeneous, more or less like in any other part of the world, and no single European model has yet emerged,19 even in the European Union directives. In general, the two types of systems do not appear to perform differently as regards the main health outcomes22 and all the Western European health systems are faced with similar problems, especially expenditure growth in this never-ending period of financial crisis,11 raising concern about the efficiency of resource use.

Critical issues

Market competition in healthcare is not supported by economic theory and required ideological support from the very first British attempt in Europe,5 which very likely stemmed from a reform driven for political purposes against purely public systems, generating − perhaps inevitably − muddle in the long run.24

The latest European review21 on public–private provider competition confirmed the evidence of all previous studies, i.e. that private hospitals (especially for-profit ones) have been involved in all the potential distortions of a ‘quasi market’ situation. Despite expectations raised by theoretical studies suggesting that private hospitals should outperform public ones in terms of efficiency, empirical results were different. Overall, public hospitals performed better than non-profit private ones, which in turn performed better than for-profit ones. In general, public hospitals tended to treat older and poorer patients with higher levels of co-morbidity and complications, whereas for-profit hospitals opted to focus on lower severity patients. Not by chance, in most European countries public hospitals are still the major providers of emergency services,25 mainly delivered through costly departments where health professionals have to be available full-time.

These performances confirm the intrinsic limits of funding through arbitrarily fixed prices per patient.16 Tariffs can hardly take account of all the cost differences related to the conditions of each specific patient, and private hospitals tend to ‘harvest the low-hanging fruits’, (obviously) privileging profits. Activity-based funding can eventually undermine coordination and synergies among hospitals, thus missing opportunities to improve quality and curtail costs.2

The potential distortions of a fee-for-service system adopted in mixed public–private provision require tight regulation and systematic audits of hospital work,26 generating high ‘transaction costs’ both ex ante and ex post the introduction of tariffs. The former include search costs (for acquiring information on providers and their services) and negotiation costs (for bargaining and agreeing contracts), the latter include monitoring costs (mainly to counter opportunistic behaviours) and enforcement costs (in case of legal disputes).27 Unsurprisingly, the US spends far more than other wealthy nations on healthcare administration,28 one of the main reasons for their skyrocketing healthcare expenditure.

In general, public investments in transaction costs are much more effective when contracting out ‘technical’ services such as garbage collection or ground maintenance than ‘social’ ones such as health. Service quality is much easier to measure in the former,15 while routinely comparing outcome quality (i.e. benefits to patients) across healthcare services is methodologically difficult. As a consequence, most negotiations ultimately revolve around prices,2 the only measure on which health providers really compete in practice, without including the quality of care.

Policy implications

The European experience of health competition in the last few decades − mainly focused on providers − has failed overall, as expected. Competition is just a means, not an end in itself,5 so proceeding in this direction would be a really questionable strategy mainly driven by ideology, in permanent contradiction with health economics theory − and common sense too.

In general, competition is not the best instrument for addressing equity concerns in healthcare,1 so health needs should be the ‘driver’ for patients to access care,22 not their socioeconomic status or ability to pay. Health is basic in the hierarchy of human needs and illness threatens people’s dignity,12 so healthcare should not be subjected to market rules in an advanced society. However, from theory to practice, it would be utopian to imagine a fully equitable health system, where wealthy patients do not have any advantage over poor ones, like in any other domain, and private systems exist precisely so that rich people can ‘opt out’ and look after themselves.24 We contend, however, that private and public healthcare services can co-exist, but separately, and all citizens should contribute to the costs of a public system for social solidarity in advanced countries, no matter whether they use it or not. Thus, too, any form of physicians’ dual practice (public and private) should be forbidden,12 to prevent conflicts of interest in the medical profession at the micro level. Medicine is a mission aimed at serving patients, so professional ethics and success in curing or caring should be the leading motivations of health professionals.23

Once agreed on these basic principles, it is hard to deny that ideally a public health system should be privileged and supported in a European perspective. For funding, it is pretty obvious to claim that the public sector is potentially the best ‘insurer’ to grant universal coverage, reducing transaction costs to ‘in-house’ administrative costs15 and keeping total healthcare expenditure more easily under control.27

The choice for public provision is less obvious. Despite evidence of opportunistic behaviours by private providers (especially for-profit),21 it is fair to recognise that public provision is open to both central and local political influence.11 For instance, most efforts to make public hospital networks more rational by closing inefficient services and/or reducing their employees have often failed, mainly because of trade unions and political resistance, eventually leading to arguable reorganisations. The big challenge in the future is to limit these ‘bad influences’ and efficiently manage the provision of public services for both primary and secondary care, improving internal organisational skills for planning and control, like in a big company. Rather than pricing and competing, planning and budgeting could be the right ‘culture’ to borrow from the private sector for managing public healthcare services. All physicians should be employees (general practitioners included) so their practice can be supervised more effectively,29,30 and outputs could be periodically audited by independent bodies.31 The adoption of electronic medical records and other modern computerised reporting systems should technically facilitate the systematic monitoring of health service performances.11

Once the essential levels of care to be guaranteed by health systems are clearly set, we are still convinced that most patients would rather use services provided close to where they live,24 easier to obtain through collaborative rather than adversarial relationships inside health systems.5 While private providers − with the partial exception of non-profit ones − tend to choose their markets and services, by definition, public providers are used to supplying the required services to all citizens in a given area.15 So we would opt for the latter for provision too, accepting the big challenge to develop the best incentives for limiting traditional public sector bureaucracy and improving the quality of care.4 Governance should be inspired by collaboration and integration among services,8 where financial incentives are not needed to make health professionals work harder for patients.17

To conclude, although it is hard to prevent myths developing, we must identify them to limit their ultimate harm. Here we contend that the time has come to stop promoting market competition in healthcare, and focus future research on how to boost the quality of public health services in Europe.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

LG.

Contributorship

Authors contributed equally to the article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our friend Paris Tsebras for his useful comments on the draft of the manuscript.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Nick Freemantle.

References

- 1.Barros PP, Brouwer WB, Thomson S, Varkevisser M. Competition among health care providers: helpful or harmful? Eur J Health Econ 2016; 17: 229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siciliani L, Chalkley M, Gravelle H. Policies towards hospital and GP competition in five European countries. Health Policy 2017; 121: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso JM, Clifton J, Díaz-Fuentes D. Did new public management matter? An empirical analysis of the outsourcing and decentralization effects on public sector size. Public Manag Rev 2015; 175: 643–660. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltman RB. Melting public-private boundaries in European health systems. Eur J Pub Health 2003; 13: 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard A, Bloor K. Universal coverage and cost control: the United Kingdom National Health Service. J Health Hum Serv Adm 1998; 20: 423–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell M, Béland D, Waddan A. The Americanization of the British National Health Service: a typological approach. Health Policy 2018; 122: 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See https://www.hsj.co.uk/finance-and-efficiency/revealed-14-trusts-start-contingency-plans-after-carillion-collapse/7021461.article (last checked 30 October 2018).

- 8.Burau V, Dahl HM, Jensen LG, Lou S. Beyond activity based funding: an experiment in Denmark. Health Policy 2018; 122: 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper Z, Gibbons S and Skellern M. Does Competition From Private Surgical Centres Improve Public Hospitals' Performance? Evidence from the English National Health Service. Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper 1434, 2016. See http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67662 (last checked 14 November 2018).

- 10.Baxter PE, Hewko SJ, Pfaff KA, Cleghorn L, Cunningham BJ, Elston D, et al. Leaders experiences and perceptions implementing activity-based funding and pay-for-performance hospital funding models: a systematic review. Health Policy 2015; 119: 1096–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saltman RB. The impact of slow economic growth on health sector reform: a cross-national perspective. Health Econ Policy Law 2018; 13: 382–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garattini L, Padula A. Dual practice of hospital staff doctors: hippocratic or hypocritic? J R Soc Med 2018; 111: 265–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garattini L, Padula A. Patient empowerment in Europe: is no further research needed? Eur J Health Econ 2018; 19: 637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garattini L, van de Vooren K. Could co-payments on drugs help to make EU health care systems less open to political influence? Eur J Health Econ 2013; 14: 709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen OH, Hjelmar U and Vrangbæk KI. Contracting out of public services still the great panacea? A systematic review of studies on economic and quality effects from 2000 to 2014. Soc Policy Admin 2017. See 10.1111/spol.12297 (last checked 14 November 2018). [DOI]

- 16.Street A, Sivey P, Mason A, Miraldo M, Siciliani L. Are English treatment centres treating less complex patients? Health Policy 2010; 94: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock AM. Morality and values in support of universal healthcare must be enshrined in law. Comment on “Morality and Markets in the NHS”. Int J Health Policy Manag 2015; 4: 399–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garattini L, Padula A. Pharmaceutical pricing conundrum: time to get rid of it? Eur J Health Econ 2018; 19: 1035–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendt C. Changing healthcare system types. Soc Policy Admin 2014; 48: 864–888. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohm K, Schmid A, Gotze R, Landwehr C, Rothgang H. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Policy 2013; 113: 258–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tynkkynen LK, Vrangbæk K. Comparing public and private providers: a scoping review of hospital services in Europe. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 141–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Or Z, Cases C, Lisac M, Vrangbaek K, Winblad U, Bevan G. Are health problems systemic? Politics of access and choice under Beveridge and Bismarck systems. Health Econ Policy Law 2010; 5: 269–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maynard A. Health care rationing: doing it better in public and private health care systems. J Health Polit Policy Law 2013; 38: 1103–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams A. Priority setting in public and private health care: a guide through the ideological jungle. J Health Econ 1988; 7: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorvatn A. Private or public hospital ownership: does it really matter? Soc Sci Med 2018; 196: 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenna E. Quasi-market and cost-containment in Beveridge systems: the Lombardy model of Italy. Health Policy 2011; 103: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marini G, Street A. A transaction costs analysis of changing contractual relations in the English NHS. Health Policy 2007; 83: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 2018; 319: 1024–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard A. Put all GPs on a salaried contract. BMJ 2015; 350: h2254–h2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garattini L, Curto A, Freemantle N. Access to primary care in Italy: time for a shake-up? Eur J Health Econ 2016; 17: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith PC. Measuring health system performance. Eur J Health Econ 2002; 3: 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]