Abstract

Background:

An overview of systematic reviews (SRs) and a network meta-analysis (NMA) were conducted to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies used either alone, or as an add-on to other irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) treatments.

Methods:

A total of eight international and Chinese databases were searched for SRs of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The methodological quality of SRs was appraised using the AMSTAR instrument. From the included SRs, data from RCTs were extracted for the random-effect pairwise meta-analyses. An NMA was used to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different treatment options. The risk of bias among included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Results:

From 15 SRs of mediocre quality, 27 eligible RCTs (n = 2141) were included but none performed proper blinding. Results from pairwise meta-analysis showed that both needle acupuncture and electroacupuncture were superior in improving global IBS symptoms when compared with pinaverium bromide. NMA results showed needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula had the highest probability of being the best option for improving global IBS symptoms among 14 included treatment options, but a slight inconsistency exists.

Conclusion:

The risk of bias and NMA inconsistency among included trials limited the trustworthiness of the conclusion. Patients who did not respond well to first-line conventional therapies or antidepressants may consider acupuncture as an alternative. Future trials should investigate the potential of (1) acupuncture as an add-on to antidepressants and (2) the combined effect of Chinese herbs and acupuncture, which is the norm of routine Chinese medicine practice.

Keywords: acupuncture, acupuncture points, acupuncture therapy, irritable bowel syndrome, network meta-analysis, systematic review

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional bowel condition, which is characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of an organic disease.1 Conventional treatment for IBS has been oriented towards the symptomatic management of diarrhea, constipation, pain, cramping and bloating.2 Exercise and dietary manipulation, such as low FODMAP diet, are key first-line treatment options.3–5 The United Kingdom (UK) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)6 and the World Gastroenterology Organization global guideline7 recommend antispasmodics as first-line therapy for relieving global IBS symptoms. However, antispasmodics may lead to adverse events, including dry eyes and mouth, and blurred vision.8 An antidiarrheal, loperamide, is also recommended in relieving diarrhea among IBS patients in NICE guidelines,6 but it may result in potential side effects, such as dizziness and vomiting.9 Antidepressants are suggested to be effective in global symptom relief among IBS patients, yet adverse events, public acceptability and their availability in the primary care setting have restricted their use.10 Other commonly used strategies for managing diarrhea (e.g. probiotics) and constipation (fiber and polyethylene glycol) are ineffective for reducing overall and abdominal symptoms.10,11

In the United States (US), only one-third of IBS patients show satisfaction with their current therapies.12 Lack of effectiveness and associated adverse effects are common reasons for dissatisfaction.12 In view of these treatment gaps, some patients turn to traditional, complementary and integrative medicine (TCIM). In Australia, a population-based survey showed that about 21% of IBS patients had consulted a TCIM practitioner.13 In the UK, the prevalence of TCIM use among IBS patients attending outpatient specialist clinics was as high as 50%.14 In the US, a cohort study among functional bowel disorder patients suggested that the incidence of TCIM use was 35% over a 6-month period.15 In China, the use of Chinese medicine is prevalent among chronic disease patients.16,17 Acupuncture and related therapies, as well as Chinese herbal medicine, have been extensively used for treating functional gastrointestinal disorders, including IBS.18,19

Despite their wide usage, existing clinical evidence on acupuncture is conflicting. In a Cochrane review of two trials, needle and sham acupuncture were found to be of similar effect in improving IBS symptoms.20 However, another meta-analysis showed that needle acupuncture provided stronger effects in IBS symptom relief than pharmacological therapies.21 The three other systematic reviews (SRs) suggested that needle acupuncture plus moxibustion was superior to pharmacological therapies for reducing IBS symptoms.22–24 Inconsistent evidence summarized in different SRs makes it difficult to conclude whether acupuncture and related therapies may be used as a complement to, or an alternative treatment option for IBS.

In order to address the uncertainty described above, we conducted an overview of SRs to synthesize and critically appraise all clinical evidence on the comparative effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies used either alone, or as an add-on to other treatments, compared with other IBS treatments using a network meta-analysis (NMA) approach.25

Methods

Inclusion criteria

The definition of an SR was adopted from the most updated Cochrane Handbook (version 5.1.0), which defines an SR as an ‘attempt to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets prespecified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question.’26 Based on the definition, we judged a publication as an SR if it answered a research question by searching at least two electronic databases.27

To be included in this overview, SRs had to be in either the English or Chinese language and satisfy the criteria for participants, intervention, comparisons and outcomes of interest listed below. Individual randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were then retrieved from eligible SRs, which is a common approach used in NMA.28

Participants

Patients diagnosed with IBS by any defined diagnostic criteria were included. The Manning criteria,29 the Kruis criteria,30 Rome I,31 Rome II,1 and Rome III criteria32 as well as the recent Rome IV criteria33 were considered as eligible, among other commonly used clinical criteria in China. There was no restriction on patients’ other characteristics or comorbidities.

Intervention and comparisons

In this overview of SRs, ‘acupuncture and related therapies’ was defined as single or combined use of needle acupuncture, moxibustion, electroacupuncture, periorbital acupuncture and catgut embedding (Table 1).34–37 Acupuncture and related therapies including the single or combined use of these acupuncture modalities were considered eligible for this overview. SRs with studies providing any type of control treatments were considered, including conventional pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments, as well as Chinese herbal medicine. Regardless of control treatment, to be eligible a trial must allow the estimation of net effect of acupuncture and related therapies.

Table 1.

Definitions of acupuncture and related therapies in this overview of systematic reviews.

| Needle acupuncture | Needle insertion into acupuncture points, followed by manual manipulation such as lifting and thrusting, twirling and rotating, or a combination of the two. The function of needling is believed to promote Qi (the vital energy) in the meridians in order to produce its therapeutic effect. |

| Moxibustion | A method in which a moxa herb is burned above the skin or on the acupuncture points. It can be used a cone, stick, loose herb, or applied at the end of the acupuncture needles. The purpose of moxibustion is to alleviate symptoms by applying heat to the acupuncture points. |

| Electroacupuncture | A modern acupuncture technique used with manual acupuncture, where needle is attached to a trace pulse current after it is inserted to the selected acupoint for producing synthetic effect of electric and needling stimulation. |

| Periorbital acupuncture | A form of needle acupuncture in which the acupoints around the eyes are used. |

| Catgut embedding | An acupuncture technique which involves weekly infixing of surgical chromic catgut sutures into the subcutaneous tissue of acupoints located at the abdomen, extremities and the back with a specialized needle under aseptic precautions. |

Outcome of interest

To be included in an NMA, trials should include at least one of the following outcomes: (1) IBS symptom improvement, measured with either global or individual symptom scores; or (2) proportion of patients reaching satisfactory relief of global or individual symptoms. These outcomes were chosen based on current reviews on the primary endpoints of IBS clinical trials.38 Primary outcomes of symptom improvement were usually reported on short, 3 or 4-point Likert scales. Following recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook, these short ordinal outcome results were dichotomized into ‘improvement’ or ‘no improvement’ in judging clinical effectiveness.26 Similarly, binary assessment of global symptom improvement is also accepted as an approach for outcome evaluation in IBS trials.39

Since results of all 3-point Likert scales were categorized as ‘markedly effective,’ ‘effective’ and ‘no improvement’ while those of all 4-point Likert scale were categorized as ‘clinical remission,’ ‘markedly effective,’ ‘effective’ and ‘no improvement,’ the categories of ‘clinical remission,’ ‘markedly effective’ or ‘effective’ results were combined into a category named ‘improvement,’ while ‘no improvement’ was labelled as a nonbeneficial category in all analyses.

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search for SRs was conducted in eight databases from inception until December 2017. Potential SRs were searched through both international databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect) and Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Databases, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wan Fang Digital Journals and Taiwan Periodical Literature Databases) without language or publication status restrictions. Specialized search filters for reviews were used in MEDLINE40 and EMBASE.41 Detailed search strategies are shown in Appendix 1.

Literature selection, data extraction, methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

Eligible SRs were selected independently by two researchers (CHLW and WKWC). They conducted data extraction, assessment of methodological quality of eligible SRs and risk of bias of included RCTs independently. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus between them. Further unresolved discrepancy was managed by a third reviewer (IXYW).

Citations of SRs generated through database searches were screened and assessed for eligibility. Lists of included RCTs were retrieved from eligible SRs. For duplicate or overlapping RCT publications, the single most updated and comprehensive version was chosen. To be included in the NMA, RCTs had to include a common control intervention that provides a bridge for the indirect comparison of different acupuncture interventions.

The following data were extracted from each included RCT: year of publication, source of patients, number of patients enrolled, diagnostic criteria used, duration of IBS diagnosis, patient characteristics, details of interventions, types of outcome assessment, reporting of adverse events, as well as information for assessing risk of bias.

The methodological quality of included SRs was assessed using the AMSTAR instrument,42 which is a reliable and validated tool for conducting appraisal in overviews of SRs.43 In total, 11 aspects were assessed by using AMSTAR according to the information provided. Each aspect was judged as yes, no, cannot answer or not applicable. The risk of bias of each retrieved RCT was assessed with the Cochrane risk of bias tool.44 Overall, six domains in the risk of bias, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting, were assessed, with each domain being judged as having low, unclear, or high risk of bias based on the information reported in each RCT publication.

Data synthesis

In this overview of SR, we followed established methods of conducting pairwise meta-analyses, followed by an NMA, which are considered as standard methodology in the field.45 Pairwise random-effect model meta-analyses were used to synthesize data separately from individual types of acupuncture and related therapies or add-on of acupuncture and related therapies to control treatment, by comparing with identical control treatments.46 For dichotomous data extracted from RCTs, pooled relative risks (RRs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to quantify the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies on IBS symptoms improvement. Heterogeneity across RCTs was tested with a Chi-square test and a p value < 0.1 was considered as an indicator of significant heterogeneity. The level of heterogeneity was measured with the I2 statistic, with I2 <25% regarded as a low level, 25–50% as a moderate level and >50% as a high level.47

NMA is a preferred approach which offers a set of methods to visualize and interpret the wider picture of existing evidence, as well as to understand the comparative effectiveness of these multiple treatments.48 It provides indirect evidence (comparison between different treatments via common comparators) when direct evidence (head-to-head comparison of different treatments) is unavailable.25 It was conducted to explore, relatively speaking, the ‘most’ effective option for improving IBS symptoms among included interventions. With the common comparator of control interventions, indirect comparisons between different interventions on the effectiveness of IBS symptoms improvement were implemented with the ‘mvmeta’ command in STATA.49,50

Network geometry was presented to describe the types of treatments in the network of comparisons using a network graph.51 Comparative effectiveness ranking results of all included interventions were summarized from NMA. The probability of each intervention being, relatively, the ‘most’ effective treatment option, the second-best treatment and so on was deduced. SUCRA, the surface under the cumulative ranking curve,52 is used to provide an effectiveness hierarchy. The larger the SUCRA, the higher effectiveness ranking the treatment would have. This data analysis was conducted using STATA version 13.0.

Consistency of direct evidence and indirect evidence on the same comparison is a key assumption in NMA.50 In this NMA, loop-specific approach was used to assess consistency of each individual closed loop of the network, by comparing direct and indirect estimates of a specific comparison.49 Presence of inconsistency in each loop was measured by the ratio of odds ratios (RoRs) between direct and indirect evidence results in the loop. A RoR value close to 1 indicates that the two evidence sources were consistent,49 and the result was presented in an inconsistency factor (IF) plot. The consistency assessment is implemented using the ‘ifplot’ command in STATA.49

Sensitivity analysis was carried out by excluding studies of acupuncture plus Chinese herbal medicine and only including studies which explored the effectiveness of needle acupuncture, needle acupuncture plus moxibustion, electroacupuncture, moxibustion and three pharmacological therapies (pinaverium bromide, trimebutine maleate and loperamide) on IBS symptoms improvement.

Results

Results on literature search and selection

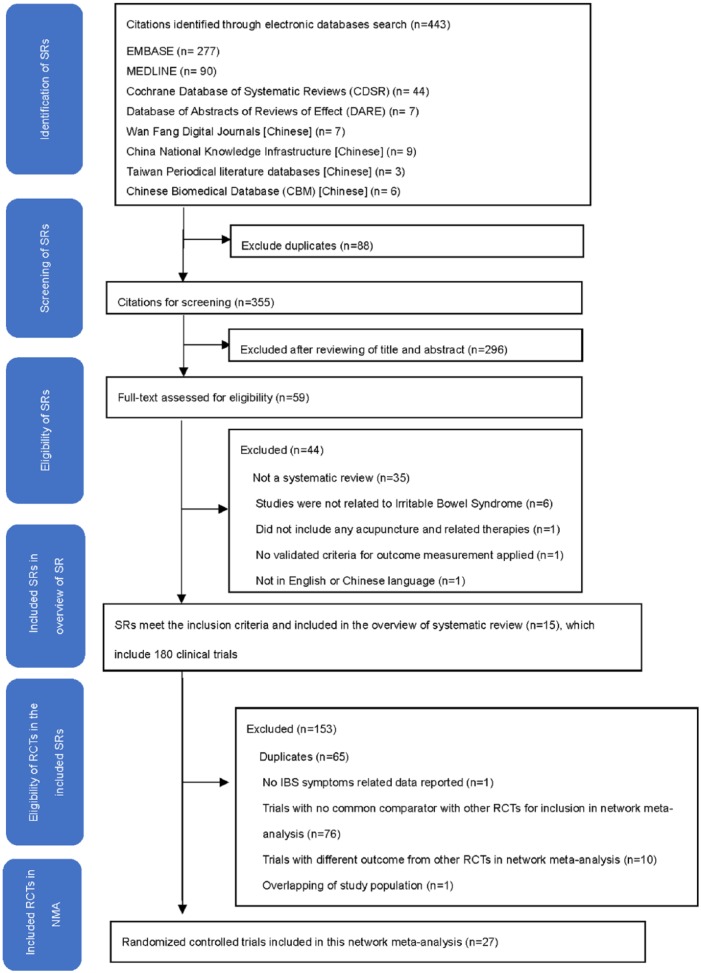

A total of 15 SRs (Appendix 2) were identified through the literature search and were considered eligible for inclusion in the overview of SRs. These 15 SRs included a total of 180 RCTs. Overall, 153 RCTs were excluded from the NMA due to the following reasons: duplicates (n = 65), no IBS symptom-related outcome data reported (n = 1), trials with no common comparator with other RCTs for inclusion in the NMA (n = 76), trials with different outcome from other RCTs in the NMA (n = 10) and overlapping of study population (n = 1). Hence, 27 RCTs (Appendix 3) were included in the NMA. Details of the literature search and selection are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature selection on systematic reviews of acupuncture and related therapies for irritable bowel syndrome.

Characteristics of included RCTs

Participants

The 27 RCTs included a total of 2141 participants, with sample sizes varying from 40 to 300 patients. The age range of participants was 18–77 years. Duration of IBS ranged from 0.25 years to 38 years. All RCTs were conducted in China among Chinese populations. A total of 13 trials included outpatients only, 11 trials included both inpatients and outpatients and 3 trials did not report the study setting.

Diagnostic criteria and subtypes of IBS

A total of 24 RCTs recruited IBS patients using Rome/Rome II/Rome III criteria. Among them, 12 conducted patient eligibility assessments with additional diagnostic criteria, including Chinese IBS guidelines or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) clinical practice guidelines. Overall, 18 recruited patients with IBS-D and 6 did not specify the subtype of IBS. For the remaining three RCTs, two recruited IBS patients using the Chinese IBS guidelines, while one did not specify the diagnostic criteria.

Interventions

A total of 14 interventions were evaluated in these 27 RCTs, including needle acupuncture (n = 12), electroacupuncture (n = 5), needle acupuncture plus moxibustion (n = 4), moxibustion (n = 2), periorbital acupuncture (n = 2), catgut embedding (n = 1), catgut embedding plus pharmacological therapy (trimebutine maleate) (n = 1), needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbal medicine (Geshanxiaoyao formula; n = 1), Geshanxiaoyao formula alone (n = 1), Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang; n = 3), Bifidobacterium (n = 1), and three different pharmacological therapies, including two antispasmodics [pinaverium bromide (n = 15) and trimebutine maleate (n = 5)) and an antidiarrheal (loperamide (n = 3)]. Composition of Geshanxiaoyao formula and Tongxieyaofang is listed in Appendix 4. The duration of interventions ranged from 14 to 56 days. All the RCTs assessed global IBS symptom improvement at the end of treatment. Characteristics of included RCTs can be found in Table 2.35,36,53–77

Table 2.

Main characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| First author, country | Source of patients | IBS diagnostic criteria, IBS subtype | Types of intervention | Details of intervention (Duration of each session (mins/session), no. of sessions/dosage (on prescription); length of intervention) |

No. of patients (A/R) |

Age range/ mean ± SD (years) | Length of time since IBS diagnosis (range/ mean ± SD) |

Types of outcomes assessment | Reporting of adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu and colleagues,75 China | Inpatient and outpatient | Chinese IBS guideline, IBS subtype: NR | Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion | Acupuncture: 40 mins/session; moxibustion: 30 mins/session; 21 sessions; 21 d |

31/31 | 22.0–66.0 | 1.00–12.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 21 d | 30/30 | 25.0–70.0 | 1.00–10.00 years | |||||

| Sun and colleagues,70 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria, IBS-D | Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/session; 20 sessions; 28 d |

30/31 | 18.0–61.0 | 1.00–20.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | No occurrence of adverse events was observed. |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 30/32 | 18.0–59.0 | 1.00–38.00 years | |||||

| Luo and colleagues,66 China | Outpatient | Rome II criteria & Chinese IBS guideline, IBS-D | Moxibustion | 30 mins/session, 60 sessions; 30 d |

48/48 | 26.0–63.0 | 1.00– 16.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 30 d | 47/47 | 24.0–62.0 | ||||||

| Liu,64 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture | Duration of each session: NR; no. of sessions: NR; 28 d | 30/30 | 42.3 ±7.6 | 2.51 years ±1.28 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 30/30 | 41.8 ± 9.0 | 2.48 years ±1.32 |

|||||

| Kong and colleagues,56 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria and TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 28 sessions; 28 d |

29/30 | 38.0 ± 11.0 | 6.21 years ±6.33 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 28/30 | 38.0 ± 11.0 | 5.40 years ± 3.85 |

|||||

| Wei and colleagues,72

China |

Outpatient | Rome II criteria, IBS subtype: NR | Needle acupuncture | 20 mins/ session, 30 sessions; 30 d |

30/30 | 15.0–66.0 | 4.37 years (SD: NR) |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (q.d.); 28 d | 30/30 | 22.0–77.0 | 3.37 years (SD: NR) |

|||||

| Liu and Wang,61

China |

Outpatient | TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS subtype: NR |

Electroacupuncture | 20 mins/ session, 24 sessions; 24 d |

30/30 | 18.0–60.0 | 0.25– 5.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 20 d | 30/30 | |||||||

| Sun and Song,71 China | Inpatient and Outpatient | Rome III criteria and TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS subtype: NR |

Electroacupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 15 sessions; 21 d |

30/30 | 38.0 ± 12.0 | 5.16 years ± 4.67 | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | No occurrence of adverse events was observed. |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 21 d | 30/30 | |||||||

| Li and colleagues,57

China |

Outpatient | Rome III criteria, IBS-D |

Electroacupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 12–14 sessions; 28 d | 35/35 | 39.1 ± 11.8 | 4.33 years ±3.93 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 35/35 | 37.9 ± 11.5 | 5.23 years ±7.35 |

|||||

| Li,59 China | Inpatient and Outpatient | Rome III criteria, TCM clinical practice guideline and Chinese IBS guideline, IBS subtype: NR |

Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 20 sessions; 20 d | 30/32 | 55.5 ± 5.4 | 3.65 years ±1.74 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 21 d | 30/32 | 55.3 ± 5.0 | 3.63 years ±1.80 |

|||||

| Li and colleagues,58 China | Inpatient and Outpatient | Rome III criteria and TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 28 sessions; 56 d | 30/30 | 46.0 ± 16.0 | 13.60 years ±9.80 | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 56 d | 30/30 | 44.0 ± 16.0 | 13.30 years ±10.10 |

|||||

| Wu and Gao,74 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria & Chinese IBS guideline, IBS subtype: NR |

Electroacupuncture | 30 mins/ session, 15 sessions; 30 d | 30/30 | 25.0–62.0 | NR | Global IBS symptoms improvement using binary assessment | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 30 d | 30/30 | 27.0–65.0 | ||||||

| Pei and colleagues,67 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria & TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/session, 20 sessions; 28 d | 30/33 | 39.1 ± 11.8 | 4.93 years ±3.93 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 30/32 | 37.9 ± 11.5 | 5.23 years ±7.35 |

|||||

| Gao,35

China |

Inpatient and outpatient | Rome III criteria & Chinese IBS guideline, IBS-D | Periorbital acupuncture | 15 mins/session, 20 sessions; 20 d | 30/32 | 37.2 ±10.2 | 4.14 years ±1.12 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | Five cases of bruises were observed in periorbital acupuncture group. |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 30/32 | 40.1 ±11.7 | 4.13 years ±1.76 |

|||||

| Liu,36 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria and TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Periorbital acupuncture | 20 mins/ session, 20 sessions; 20 d | 29/30 | 37.0 ± 10.1 | 4.08 years ±1.11 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | Five cases of bruises were observed in periorbital acupuncture group. |

| Pinaverium bromide | 50 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 29/30 | 39.7 ± 10.6 | 4.11 years ±1.58 |

|||||

| Zeng and colleagues,77 China | Inpatient and outpatient | Rome criteria, IBS-D | Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion | 20 mins/session, 30 sessions; 30 d |

29/33 | 35.2 ± 7.2 | 1.27 years ±7.85 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Trimebutine maleate | 100 mg (t.i.d.); 30 d | 31/32 | 34.7 ± 6.5 | 1.24 years ±7.77 |

|||||

| Shi and colleagues,69 China | Inpatient and outpatient | Rome II criteria, IBS subtype: NR | Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/session, 28 sessions; 28 d |

20/20 | 43.5 ± 5.3 | 0.90 year-5.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Trimebutine maleate | Dosage: NR (t.i.d.); 28d | 20/20 | 46.2 ± 4.7 | 1.00–4.50 years | |||||

| Liu,65

China |

NR | Rome III criteria, IBS-D | Needle acupuncture | 20 mins/session, 30 sessions; 35 d |

31/31 | 23.0–64.0 | 3.15 years ± 1.02 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | A few cases of nausea and rash were observed in trimebutine maleate group. |

| Trimebutine maleate | 200 mg (t.i.d.); 35 d | 31/31 | 20.0–65.0 | 3.52 years ± 0.95 |

|||||

| Shi and colleagues,68 China | Inpatient and outpatient | Rome III criteria, IBS-D | Electroacupuncture | 30 mins/session, 56 sessions; 56 d |

60/60 | 40.2 ± 10.8 | 8.60 years ± 3.80 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Trimebutine maleate | 200 mg (t.i.d.); 56 d | 60/60 | 38.5 ± 9.1 | 7.30 years ± 2.10 |

|||||

| Yao,76 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria & TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate | 7 d/session, 2 sessions plus 200 mg (t.i.d.); 14 d | 30/30 | 18.0–65.0 | NR | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | No occurrence of adverse events was observed. |

| Trimebutine maleate | 200 mg (t.i.d.); 14 d | 30/30 | 18.0–65.0 | ||||||

| Guo and colleagues,55 China | NR | Rome II criteria, IBS-D | Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion | 30 mins/session, 30 sessions; 30 d |

52/52 | 18.0–60.0 | 1.00–15.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Loperamide | 2 mg (t.i.d.); 30 d | 48/48 | 20.0–60.0 | 1.00–14.00 years | |||||

| Chu and colleagues,53 China | Inpatient & outpatient | Rome II criteria, IBS-D | Moxibustion | 30 mins/session, 15 sessions; 15 d |

30/30 | 23.0–61.0 | 0.25– 4.00 years |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Loperamide | 2 mg (b.i.d.); 15 d | 30/30 | 24.0–60.0 | 0.25– 5.00 years |

|||||

| Ge and Zeng,54

China |

NR | Rome criteria, IBS subtype: NR |

Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion | 30 mins/session, 24 sessions; 28 d |

60/60 | 38.9 ± 11.2 | 1.00–13.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Loperamide | 2 mg (t.i.d.); 28 d | 60/60 | 39.1 ± 10.3 | 1.00–12.00 years | |||||

| Liu and colleagues,63 China | Inpatient and outpatient | Rome III criteria, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbal medicine (Geshanxiaoyao formula) |

Duration of each session: NR, 28 sessions plus 150 mL (b.i.d.); 28 d | 150/150 | 45.8 ± 7.9 | 2.05 years ±3.10 |

Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | No occurrence of adverse events was observed. |

| Bifidobacterium | Dosage: NR(b.i.d.); 28 d | 50/50 | 46.2 ± 8.1 | 1.98 years ±2.92 |

|||||

| Chinese herbal medicine (Geshanxiaoyao formula) |

150 mL (b.i.d.); 28 d | 50/50 | 45.7 ± 7.9 | 2.03 years ±2.84 |

|||||

| Needle acupuncture | Duration of each session: NR, 28 sessions; 28 d | 50/50 | 46.1 ± 8.1 | 2.09 years ± 2.89 |

|||||

| Liu,62 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria & TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Catgut embedding | 7d/session, 6 sessions; 42 d | 30/30 | 37.0 ± 8.1 | NR | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | Three cases of thickening on the regions where catgut embedding was carried out were observed. |

| Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) |

1 dose/d; 42 d | 29/30 | 35.0 ± 8.7 | NR | |||||

| Wen,73 China | Outpatient | Rome III criteria & TCM clinical practice guideline, IBS-D |

Needle acupuncture | 20 mins/session, 15 sessions; length of intervention: NR |

30/30 | 18.0–65.0 | NR | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 4-point Likert scale | NR |

| Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) |

2 g (t.i.d.); 28 d | 30/30 | 18.0–65.0 | ||||||

| Liao,60 China | Inpatient and outpatient | NR | Needle acupuncture | 30 mins/session, 10 sessions; length of intervention: NR |

97/97 | 16.0–58.0 | 0.50–28.00 years | Global IBS symptoms improvement assessed on a 3-point Likert scale | NR |

| Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) |

1 dose/d; length of intervention: NR | 35/35 | 22.0–50.0 | 0.42–32 years |

A, number of patients analysed; b.i.d., two times a day; d, day; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea type; NR, not reported; q.d., once a day; mins, minutes; R, Number of patients randomized; SD, standard deviation; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; t.i.d., three times a day.

4-point Likert scale ranged from clinically remitted, markedly effective, effective to no improvement; 3-point Likert scale ranged from markedly effective, effective to no improvement; binary assessment included improvement and no improvement.

Methodological quality of included SRs and risk of bias among included RCTs

The methodological quality of the 15 SRs was mediocre. A total of 13 (86.7%) SRs performed comprehensive literature searches and assessed and documented scientific quality of the included studies. Overall, 12 (80.0%) SRs provided characteristics of the primary studies and considered the scientific quality of the study results in drawing conclusions. A total of 11 (73.3%) SRs used appropriate methods to combine the findings. Nevertheless, only one (6.67%) SR used the publication status as an inclusion criterion and provided an ‘a priori’ design. Details of the methodological quality of included SRs are presented in Appendix 5.

Among the 27 included trials, 16 (59.3%) reported details on sequence generation and used appropriate methods, and thus were judged as having a low risk of bias, while the remaining 11 did not report the procedure of sequence generation clearly. A total of 26 (96.3%) RCTs did not state any details on allocation concealment and were judged as having an unclear risk of bias. Only one (3.7%) trial reported using opaque envelopes to ensure allocation concealment. Only nine (33.3%) trials addressed how incomplete outcomes data were handled, and they were judged as having low risk of bias. All included trials had high risk of bias in blinding of participants and personnel to the intervention assignment, as well as blinding of outcome assessment. All included trials had unclear risk of bias in the domain of selective outcome reporting, as their trial protocols were unavailable. Details of risk of bias are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of bias among 28 included randomized controlled trials.

| First author | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu and colleagues75 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘All 61 patients were randomly and voluntarily divided into two groups.’ However, the method of random sequence generation was not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture plus moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 61 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Sun and colleagues70 | Low risk Quote: ‘The 63 patients were assigned by a random number table to two groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study was a single-blinded randomized control study, the blinded party was not mentioned. Blinding was not possible in the study as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk 60 out of 63 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 5.0% |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Luo and colleagues66 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘95 patients were randomly divided into two groups.’ Random sequence generation method was not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 95 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu64 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized based on admission sequence.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Kong and colleagues56 | Low risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized using a random number table into two groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 57 out of 60 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 5.0%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Wei and colleagues72 | Unclear risk Details not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu and Wang61 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized into treatment and control group.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to electroacupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Sun and Song71 | Low risk Quote: ‘60 patients were randomized using a random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to electroacupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Li and colleagues57 | Low risk Quote: ‘Patients recruited were randomized using a random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to electroacupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 70 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Li59 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘64 patients were randomized into treatment and control group.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 60 out of 64 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 6.3%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Li and colleagues58 | Low risk Quote: ‘Patients recruited were randomized using a random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Wu and Gao74 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized based on admission sequence.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to electroacupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Pei and colleagues67 | Low risk Quote: ‘65 eligible patients were randomized using a random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 60 out of 65 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 7.7%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Gao35 | Low risk Quote: ‘A random number table was used to assign included patients into treatment and control group.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to periorbital acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 60 out of 64 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 6.3%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu36 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘60 patients were assigned into treatment and control group with randomized method.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to periorbital acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 58 out of 60 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 3.3%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Zeng and colleagues77 | Low risk Quote: ‘The 65 patients were assigned by a random number table to two groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture plus moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk 61 out of 65 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 6.2% |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Shi and colleagues69 | Low risk Quote: ‘The 40 patients were assigned by simple randomization to two groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study was a single-blinded randomized control study, the blinded party was not mentioned. Blinding was not possible in the study as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 40 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu65 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized into treatment and control group.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 62 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Shi and colleagues68 | Low risk Quote: ‘Blocked randomization and random number table were used to assign 120 patients into treatment and control group.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to electroacupuncture group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 120 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Yao76 | Low risk Quote: ‘Patients were randomized using a random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to catgut embedding plus medication group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Guo and colleagues55 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘The 100 patients were assigned to two groups using a randomized design.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture plus moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 100 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Chu and colleagues53 | Low risk Quote: ‘The 60 patients were assigned by a random number table to two groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 60 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Ge and Zeng54 | Low risk Quote: ‘(Patients were) divided into a warm needling group and a western medicine group by using random digits table method.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture plus moxibustion group or medication group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 120 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu and colleagues63 | Low risk Quote: ‘The 300 patients were assigned by a random number table to four groups.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture plus Chinese herbal medicine (Geshanxiaoyao formula) group or Bifidobacterium group or Chinese herbal medicine (Geshanxiaoyao formula)-alone group or needle acupuncture alone group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 300 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liu62 | Low risk Quote: ‘Randomization was done using a random number table.’ |

Low risk Quote: ‘Random numbers were marked and put into opaque envelopes.’ |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to catgut embedding group or Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: 59 out of 60 patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 1.7%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Wen73 | Low risk Quote: ‘Two groups of patients were divided based on randomization from random number table.’ |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Low risk: All patients completed the study. Drop-out rate: 0%. |

Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

| Liao60 | Unclear risk Quote: ‘132 eligible patients were randomized into treatment and control group.’ Random sequence generation method not stated. |

Unclear risk Details not stated. |

High risk Although the study did not mention blinding of participants and researchers, blinding was not possible as participants were either randomized to needle acupuncture group or Chinese herbal medicine (Tongxieyaofang) group. |

High risk Blinding of assessors was not mentioned and its impact may be high as global IBS symptoms improvement was a subjective outcome measure. |

Unclear risk: 132 patients were randomized while the author did not mention the follow-up rate. | Unclear risk Protocol is not available. |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Results of pairwise meta-analyses

Results from pairwise random-effect meta-analyses showed that needle acupuncture was superior in improving global IBS symptoms, compared with either pinaverium bromide (pooled RR = 1.16; 95% CI: 1.07–1.27, I2 = 0%, 7 RCTs) or trimebutine maleate (pooled RR = 1.25; 95% CI: 1.05–1.49, I2 = 0%, 2 RCTs). Electroacupuncture was found to have significantly stronger effects in alleviating global IBS symptoms when compared with pinaverium bromide alone (pooled RR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.08–1.35, I2 = 0%, 4 RCTs). Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion was significantly more effective than loperamide in improving global IBS symptoms (pooled RR = 1.29; 95% CI: 1.09–1.52, I2 = 12%, 2 RCTs). Significant differences in global IBS symptom improvement was not found in the pooled results of the following comparisons: (1) Periorbital acupuncture versus pinaverium bromide and (2) Needle acupuncture versus Tongxieyaofang. Detailed results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pairwise meta-analyses: Effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for improving global IBS symptoms.

| Comparison | No. of studies | No. of patients in treatment group |

No. of patients in the control group |

Pooled RR** or RR (95% CI) | p values | I2 values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Total | Improved | Total | |||||

| Moxibustion versus pinaverium bromide | 1 | 44 | 48 | 32 | 47 | 1.35 (1.09, 1.67) | 0.006 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion versus pinaverium bromide | 1 | 28 | 31 | 24 | 30 | 1.13 (0.91, 1.40) | 0.260 | NA |

| Periorbital acupuncture versus pinaverium bromide | 2 | 48 | 59 | 36 | 59 | 1.35 (0.79, 2.30)** | 0.270 | 76% |

| Electroacupuncture versus pinaverium bromide | 4 | 114 | 125 | 94 | 125 | 1.21 (1.08, 1.35)** | <0.001 | 0% |

| Needle acupuncture versus pinaverium bromide | 7 | 184 | 209 | 153 | 208 | 1.16 (1.07, 1.27)** | <0.001 | 0% |

| Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion versus trimebutine maleate | 1 | 27 | 29 | 24 | 31 | 1.20 (0.97, 1.49) | 0.090 | NA |

| Electroacupuncture versus trimebutine maleate | 1 | 55 | 60 | 44 | 60 | 1.25 (1.05, 1.48) | 0.010 | NA |

| Catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate versus trimebutine maleate | 1 | 27 | 30 | 16 | 30 | 1.69 (1.18, 2.41) | 0.004 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture versus trimebutine maleate | 2 | 48 | 51 | 38 | 51 | 1.25 (1.05, 1.49)** | 0.010 | 0% |

| Moxibustion versus loperamide | 1 | 27 | 30 | 23 | 30 | 1.17 (0.93, 1.48) | 0.170 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture plus moxibustion versus loperamide | 2 | 97 | 112 | 72 | 108 | 1.29 (1.09, 1.52)** | 0.002 | 12% |

| Needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula versus Geshanxiaoyao formula | 1 | 135 | 150 | 37 | 50 | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45) | 0.030 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula versus Bifidobacterium | 1 | 135 | 150 | 34 | 50 | 1.32 (1.09, 1.61) | 0.005 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture versus Geshanxiaoyao formula | 1 | 33 | 50 | 37 | 50 | 0.89 (0.69, 1.15) | 0.380 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture versus Bifidobacterium | 1 | 33 | 50 | 34 | 50 | 0.97 (0.74, 1.28) | 0.830 | NA |

| Catgut embedding versus Tongxieyaofang | 1 | 25 | 30 | 24 | 29 | 1.01 (0.80, 1.27) | 0.950 | NA |

| Needle acupuncture versus Tongxieyaofang | 2 | 124 | 127 | 58 | 65 | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20)** | 0.140 | 25% |

CI, confidence interval; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio.

Bold values indicate p < 0.050.

Results of network meta-analysis

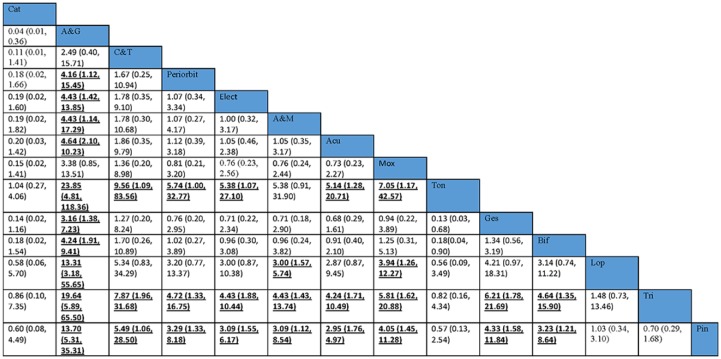

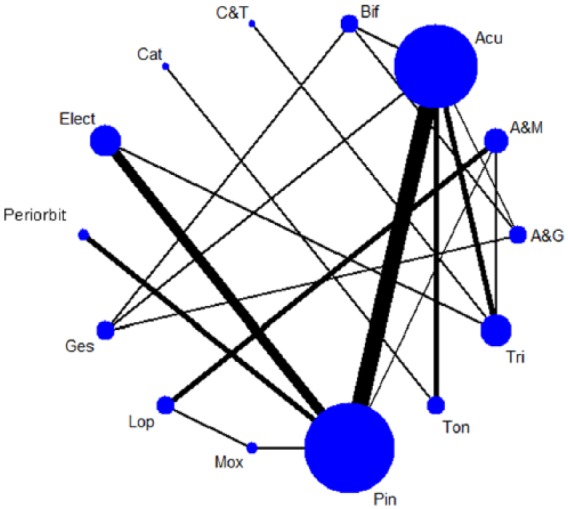

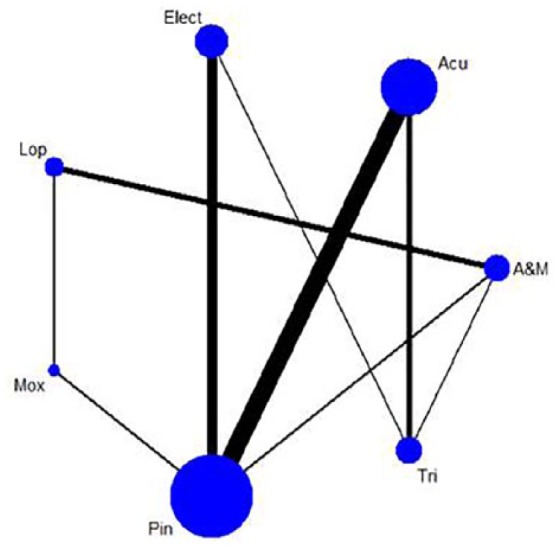

Comparative effectiveness of the 14 interventions for global IBS symptom improvement was assessed using NMA. The network of comparisons included 1 four-arm trials and 26 two-arm trials (Table 2). Both nodes and edges were weighted according to the number of studies involved in each direct comparison. The size of nodes showed that needle acupuncture was the most common comparator across the studies (Figure 2). Indirect comparison results on the dichotomous outcome of global IBS symptom improvement among these 14 treatments is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Network of comparisons in the network meta-analysis.

The width of the lines represents the proportion of the number of trials for each comparison with the total number of trials and the size of the nodes represents the proportion of the number of randomized patients (sample sizes).

Acu, needle acupuncture; A&G, needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula; A&M, needle acupuncture plus moxibustion; Bif, Bifidobacterium; Cat, catgut embedding; C&T, catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate; Elect, electroacupuncture; Ges, Geshanxiaoyao formula; Lop, loperamide; Mox, moxibustion; Periorbit, periorbital acupuncture; Pin, pinaverium bromide; Ton, Tongxieyaofang; Tri, trimebutine maleate.

Figure 3.

Odds ratio and 95% credibility intervals between 14 different interventions: indirect comparisons from network meta-analysis.

Results are the ORs and related 95% CIs in the row-defining treatment compared with the ORs in the column-defining treatment. ORs >1 favor the column-defining treatment, and vice versa. Significant result is in bold and underlined.

Acu, needle acupuncture; A&G, needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula; A&M, needle acupuncture plus moxibustion; Bif, Bifidobacterium; C&T, catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate; Cat, catgut embedding; CI, credibility interval; Elect, electroacupuncture; Ges, Geshanxiaoyao formula; Lop, loperamide; Mox, moxibustion; OR, odds ratio; Periorbit, periorbital acupuncture; Pin, pinaverium bromide; Ton, Tongxieyaofang; Tri, trimebutine maleate.

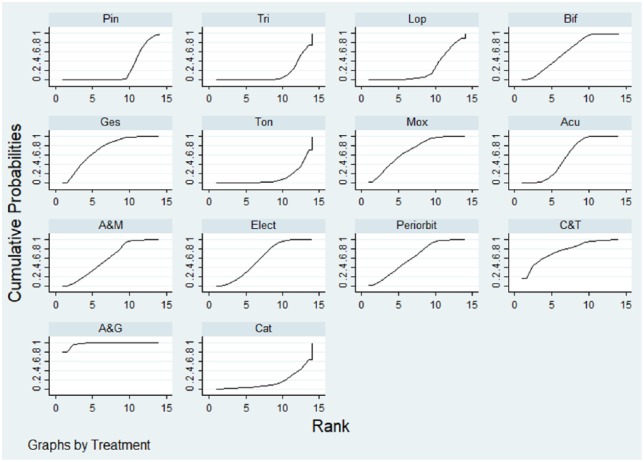

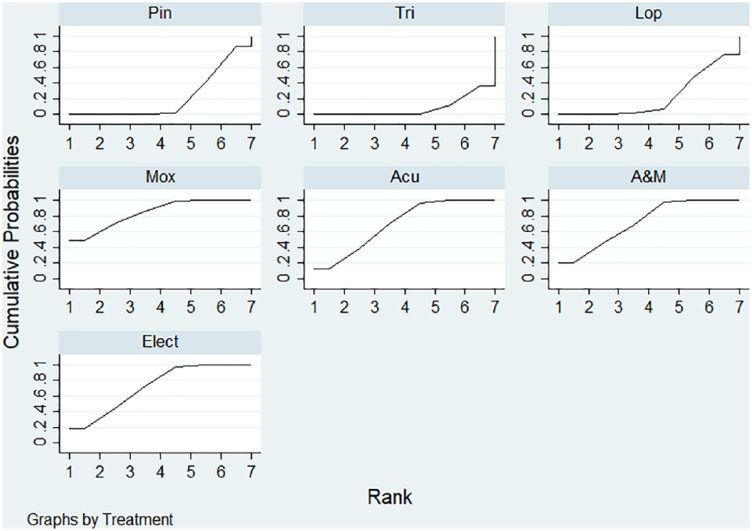

The cumulative probabilities (SUCRA results) of each included intervention being the relatively ‘most’ effective option is presented in Figure 4. The combination of needle acupuncture and Geshanxiaoyao formula had the highest probability of being the best option for improving global IBS symptoms, followed by catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate, Geshanxiaoyao formula alone and moxibustion.

Figure 4.

Comparative effectiveness of the 14 different interventions: surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) for improving overall symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients.

The x-axis represents the possible rank of each treatment (from the first best rank to the worst according to the improvement on overall IBS symptoms.) The y-axis indicates the cumulative probability for each treatment to be the best treatment, the second-best treatment, the third best treatment, and so on.

Acu, needle acupuncture; A&G, needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula; A&M, needle acupuncture plus moxibustion; Bif, Bifidobacterium; Cat, catgut embedding; C&T, catgut embedding plus trimebutine maleate; Elect, Electroacupuncture; Ges, Geshanxiaoyao formula; Lop, loperamide; Mox, moxibustion; Periorbit, periorbital acupuncture; Pin, pinaverium bromide; Ton, Tongxieyaofang; Tri, trimebutine maleate.

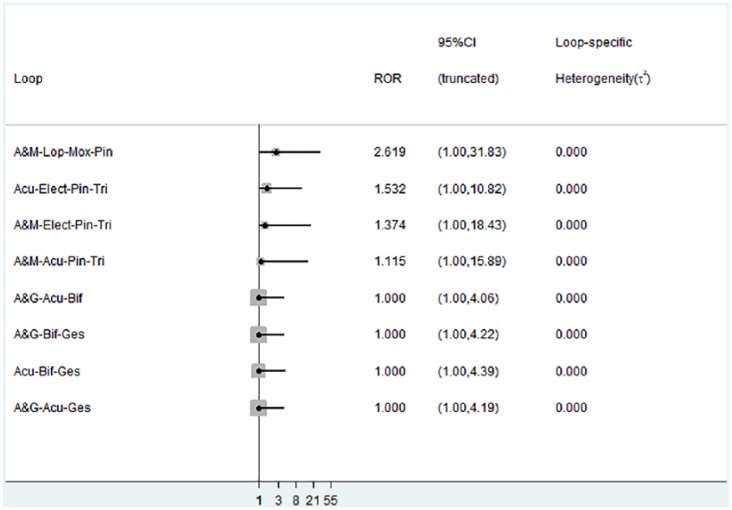

IF plot for assessment of consistency is shown in Appendix 6. The direct and indirect evidence in seven out of these eight loops were consistent, as RoRs of these seven loops were close to 1, ranging from 1.000 to 1.532. The RoRs of the remaining one quadratic loop, which included (1) needle acupuncture plus moxibustion, (2) loperamide, (3) moxibustion and (4) pinaverium bromide, was 2.619. This implied that the direct estimate could be around two times as large as the indirect estimate or vice versa.

Sensitivity analysis of the network meta-analysis

The network of the sensitivity analysis is shown in Appendix 7. The sensitivity analysis indicated that moxibustion had the highest probability for improving global IBS symptoms, followed by needle acupuncture plus moxibustion, electroacupuncture and needle acupuncture, while trimebutine maleate had the lowest probability. Detailed SUCRA results are presented in Appendix 8.

Adverse effects of acupuncture and related therapies

A total of 835,36,62,63,65,70,71,76 out of 27 included RCTs reported adverse effect rates. No serious adverse events associated with acupuncture and related therapies were reported. Bruises were observed in periorbital acupuncture group (n = 5) in two RCTs.35,36 Thickening in the area where catgut embedding was carried out (n = 3) was reported in one RCT.62 All of these events resolved in 3–5 days and participants continued to receive the treatment. A few cases of nausea and rash were reported in trimebutine maleate group in one RCT.65 No occurrence of adverse events was observed in remaining four RCTs.63,70,71,76

Discussion

In this overview, among the 24 RCTs which recruited IBS patients using various version of the Rome diagnostic criteria, of which 17 adopted Rome III. Rome III has been commonly used as one of the IBS diagnostic criteria since it was introduced in 2006. With increasing IBS knowledge in the past decade, it was modified to the latest Rome IV criteria.78 One of the major differences between Rome III and Rome IV criteria is that the frequency of recurrent abdominal pain increased from 3 days per month to 1 day per week on average.79 A recent study conducted by Vork and colleagues suggested that Rome IV IBS patients was likely a subgroup of Rome III IBS patients with more severe symptoms.80 Hence, results from our study may not be directly applicable to IBS patients diagnosed with Rome IV criteria. Future trials might investigate the effect of acupuncture and related therapies for Rome IV IBS patients.

According to the NICE guideline,6 acupuncture is not recommended for treating IBS, due to limited evidence for its effectiveness. Pairwise meta-analyses results from our study indicated that needle acupuncture, electroacupuncture and needle acupuncture plus moxibustion were significantly more effective in alleviating global IBS symptoms when compared with antispasmodics and loperamide, which are pharmacological treatments suggested in the NICE guideline. Even in our NMA sensitivity analysis, the results indicated that moxibustion had the highest probability for improving global IBS symptoms while trimebutine maleate alone had the lowest probability. These results might add to the emerging evidence base on the effectiveness of acupuncture and related therapies for IBS.

In Chinese medicine practice, acupuncture and related therapies are frequently used in conjunction with Chinese herbal medicine, and this combined treatment is generally assumed to provide better treatment effects.81,82 NMA results suggested that the combination of needle acupuncture with Geshanxiaoyao formula had the highest probability being the best treatment option for improving global IBS symptoms. This reconfirmed the multimodal approach adopted in traditional practice. However, since Chinese herbal medicine was not a main focus in this overview, future SRs should comprehensively assess the combined effect of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine.

Concurring with previous overviews on acupuncture safety,83 no serious adverse events associated with acupuncture and related therapies were reported among the included studies. Taking into account potential adverse effects of these pharmacological therapies, including dry eyes and mouth from antispasmodics,8 dizziness and vomiting from antidiarrheals,9 IBS patients who are intolerant of these adverse effects may consider using acupuncture and related therapies as alternatives. Nevertheless, since all included RCTs were conducted in China among Chinese populations, generalizability of our results among different populations and geographical locations should be considered.

Limitations and recommendations for research

Firstly, antidepressants are suggested as the second-line treatment for IBS,6 but in this overview we did not locate any trials evaluating the comparative effectiveness of antidepressants and acupuncture, or the potential of using acupuncture as an add-on to antidepressants. These comparisons should be a priority for future trials.

Secondly, the methodological quality of included SRs was assessed as mediocre. The majority of the included reviews performed a comprehensive literature search and included characteristics of primary studies. Most of them also applied appropriate method to combine findings. However, there was still room for improvement, especially in the domains including grey literature and publishing SR protocols. In future, the reporting standards of SRs should follow the PRISMA requirement.84

Thirdly, due to poor reporting, most of the included RCTs are regarded as having an unclear risk of bias in the domains of allocation concealment and selective outcome reporting. This may possibly reduce the trustworthiness of our conclusions. To improve the usefulness of study results, future trials should adhere to the CONSORT reporting statement.85

Fourthly, the primary outcome of this study was subjective global IBS symptom improvement but blinding of patients and investigators were not performed in all included RCTs. This risk of bias may introduce further uncertainty to our conclusion.86 In addition, a more comprehensive assessment on patient-centered outcomes should be added in future pragmatic trials. Additional outcomes including the Bristol stool form scale,87 individual symptom assessment and IBS quality of life questionnaires,88 should be considered.

Lastly, the follow-up duration of all included RCTs ranged from 2 to 7 weeks. Longer term effects of acupuncture and related therapies should be evaluated in future trials, for instance at 12 and 24 weeks of follow up.89,90 Close monitoring and adequate reporting of all adverse events also needs to be considered by future investigators in this field.

Conclusion

In this overview of SRs and NMA, the combination of needle acupuncture and Geshanxiaoyao formula is suggested to have the highest probability of being the most effective treatment for improving global IBS symptoms. In sensitivity analysis where the combined use of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine was excluded, moxibustion showed the highest probability of being the most effective treatment for improving global IBS symptoms. However, trustworthiness of this conclusion is limited by lack of blinding and allocation concealment, possible selective outcome reporting. In view of such limitation, (1) needle acupuncture plus Geshanxiaoyao formula and (2) moxibustion could be alternative to those who are not responsive to first-line conventional therapies, or intolerant of the adverse effects of pharmacological treatments.

Acknowledgments

The following contributed to this work. Study concept and design: C.W. and V.C. Acquisition of data: C.W. and W.C. Interpretation of data: C.W. and I.W. Figures 1–4 preparation: C.W. Tables 1–4 preparation: C.W. Appendix 1–8 preparation: C.W. Drafting of the manuscript: C.W. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: I.W., H.C., A.F., J.W., S.W. and V.C., Administrative, technical, or material support: R.H. All authors reviewed the manuscript, agreed to all the contents and agreed the submission.

Appendix 1: search strategies and results for systematic review on acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome

(i) EMBASE from inception to 12 December 2017

| 1 | meta-analys:.mp. | 223,628 |

| 2 | search:.tw. | 453,738 |

| 3 | review.pt. | 2,346,395 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 2,774,132 |

| 5 | exp irritable bowel syndrome/ | 22,094 |

| 6 | irritable bowel syndrome$.mp. | 17,919 |

| 7 | irritable colon.mp. | 22,245 |

| 8 | gastrointestinal disease$.mp. | 91,777 |

| 9 | gastrointestinal syndrome$.mp. | 311 |

| 10 | Colonic Disease$.mp. | 2019 |

| 11 | colon disease$.mp. | 10,873 |

| 12 | ((irritable or functional or spastic) and (bowel or colon)).mp. | 45,584 |

| 13 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 | 143,852 |

| 14 | exp Acupuncture/ | 41,273 |

| 15 | acupunctur*.mp. | 40,752 |

| 16 | exp Acupuncture Points/ | 41,273 |

| 17 | exp Acupuncture Therapy/ | 41,273 |

| 18 | exp Acupuncture Analgesia/ | 1522 |

| 19 | exp Electroacupuncture/ | 5565 |

| 20 | electroacupunctur*.mp. | 6387 |

| 21 | electro-acupunctur*.mp. | 1111 |

| 22 | acupoint*.mp. | 5280 |

| 23 | exp Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation/ | 714 |

| 24 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulat*.mp. | 343 |

| 25 | percutaneous electrical nerve stimulat*.mp. | 73 |

| 26 | TENS.mp. | 13,275 |

| 27 | 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | 57,051 |

| 28 | 4 and 13 and 27 | 277 |

(ii) MEDLINE from inception to 12 December 2017

| 1 | meta analysis.mp,pt. | 133,692 |

| 2 | review.pt. | 2,432,940 |

| 3 | search:.tw. | 333,880 |

| 4 | 1 or 2 or 3 | 2,667,117 |

| 5 | exp irritable bowel syndrome/ | 6669 |

| 6 | irritable bowel syndrome$.mp. | 11,697 |

| 7 | gastrointestinal disease$.mp. | 43,831 |

| 8 | gastrointestinal syndrome$.mp. | 232 |

| 9 | Colonic Disease$.mp. | 21,643 |

| 10 | colon disease$.mp. | 700 |

| 11 | ((irritable or functional or spastic) and (bowel or colon)).mp. | 24,753 |

| 12 | irritable colon.mp. | 463 |

| 13 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 | 85,118 |

| 14 | exp Acupuncture/ | 1591 |

| 15 | acupunctur*.mp. | 23,250 |

| 16 | exp Acupuncture Points/ | 5610 |

| 17 | exp Acupuncture Therapy/ | 21,989 |

| 18 | exp Acupuncture Analgesia/ | 1181 |

| 19 | exp Electroacupuncture/ | 3420 |

| 20 | electroacupunctur*.mp. | 4135 |

| 21 | electro-acupunctur*.mp. | 713 |

| 22 | acupoint*.mp. | 3669 |

| 23 | exp Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation/ | 7758 |

| 24 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulat*.mp. | 4459 |

| 25 | percutaneous electrical nerve stimulat*.mp. | 47 |

| 26 | TENS.mp. | 9735 |

| 27 | 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | 37,574 |

| 28 | 4 and 13 and 27 | 90 |

(iii) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) from inception to 12 December 2017

| 1 | irritable bowel syndrome.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 83 |

| 2 | irritable bowel syndrome$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 85 |

| 3 | irritable colon.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 10 |

| 4 | gastrointestinal disease$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 79 |

| 5 | gastrointestinal syndrome$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 5 |

| 6 | colonic disease$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 35 |

| 7 | colon disease$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 9 |

| 8 | ((irritable or functional or spastic) and (bowel or colon)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 360 |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | 436 |

| 10 | Acupuncture.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 482 |

| 11 | acupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 483 |

| 12 | Acupuncture Points.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 88 |

| 13 | Acupuncture Therapy.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 91 |

| 14 | Acupuncture Analgesia.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 23 |

| 15 | Electroacupuncture.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 84 |

| 16 | electroacupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 87 |

| 17 | electro-acupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 58 |

| 18 | acupoint*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 63 |

| 19 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 52 |

| 20 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulat*.mp. | 52 |

| 21 | percutaneous electrical nerve stimulat*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, keywords, caption text] | 6 |

| 22 | TENS.mp. | 162 |

| 23 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 | 563 |

| 24 | 9 and 23 | 44 |

(iv) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) from inception to 12 December 2017

| 1 | irritable bowel syndrome.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 110 |

| 2 | irritable bowel syndrome$.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 110 |

| 3 | irritable colon.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 0 |

| 4 | gastrointestinal disease$.mp. | 85 |

| 5 | gastrointestinal syndrome$.mp. | 0 |

| 6 | colonic disease$.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 51 |

| 7 | colon disease$.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 0 |

| 8 | ((irritable or functional or spastic) and (bowel or colon)).mp. | 152 |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 | 261 |

| 10 | Acupuncture.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 471 |

| 11 | acupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 471 |

| 12 | Acupuncture Points.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 77 |

| 13 | Acupuncture Therapy.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 312 |

| 14 | Acupuncture Analgesia.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 31 |

| 15 | Electroacupuncture.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 56 |

| 16 | electroacupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 56 |

| 17 | electro-acupunctur*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 26 |

| 18 | acupoint*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 47 |

| 19 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 52 |

| 20 | Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulat*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 52 |

| 21 | percutaneous electrical nerve stimulat*.mp. [mp=title, full text, keywords] | 1 |

| 22 | TENS.mp. | 58 |

| 23 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 | 533 |

| 24 | 9 and 23 | 7 |

(v) Wan Fang Digital Journals [Chinese] from inception to 12 December 2017

(‘系统综述’ OR ‘荟萃分析’ OR ‘META’) AND (‘针灸’ OR ‘针刺’ OR ‘电针’ OR ‘耳针’ OR ‘头针’ OR ‘水针’) AND (‘肠易激综合症’ OR ‘IBS’) 7

(vi) China National Knowledge Infrastructure [Chinese] from inception to 12 December 2017

(KY=‘系统综述’ OR KY=‘荟萃分析’ OR KY=‘META’) AND (KY=‘肠易激综合症’ OR KY=‘IBS’) 9

(vii) Taiwan Periodical Literature Databases [Chinese] from inception to 12 December 2017

(TX=系統綜述 OR 薈萃分析 OR META) [AND] (TX=針灸 OR 針刺 OR 電針 OR 耳針 OR 頭針 OR 水針) [AND] (TX=腸易激綜合症 OR IBS) 3

(viii) Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM) [Chinese] from inception to 12 December 2017

(‘系统综述’[全字段] OR ‘荟萃分析’[全字段] OR ‘META’[全字段]) AND (‘针灸

‘[全字段]) AND (‘肠易激综合症’ [全字段] OR ‘IBS’ [全字段]) 6

Appendix 2. List of included systematic reviews

- 1. Manheimer E, Wieland LS, Cheng K, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 835–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Suen NY, Zhong L. Acupuncture therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review. Master’s thesis [Chinese]. Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of TCM, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hussain Z, Quigley E. Systematic review: complementary and alternative medicine in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23: 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park JW, Lee BH, Lee H. Moxibustion in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013; 13: 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schneider A, Streitberger K, Joos S. Acupuncture treatment in gastrointestinal diseases: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 3417–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao C, Mu JP, Cui YH, et al. Meta-analysis on acupuncture and moxibustion for irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Chin Arch Trad Chin Med 2010; 28: 961–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pei LX, Zhang XC, Sun JH, et al. Meta-analysis of acupuncture-moxibusion in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Chin Acu & Mox 2012; 32: 957–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim B, Manheimer E, Lao L, et al. Acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 4: 1–24. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005111.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chao GQ, Zhang S. Effectiveness of acupuncture to treat irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 1871–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA 2015; 313: 949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grundmann O, Yoon SL. Complementary and alternative medicines in irritable bowel syndrome: an integrative view. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 346–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li RG, Wang W, Xu R, et al. Meta-analysis of acupuncture in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Glob Trad Chin Med 2016; 9: 773–776. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu JY, Chen YH. Effects of acupuncture treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trad Med Res 2016; 1: 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng DX, Guo KK, Tan J, et al. Acupuncture for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis [Chinese]. Chin Acu & Mox 2017; 37: 907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu GX, Huang BQ, Xiong J. Systematic review of acupuncture therapies for irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Chin Arch Trad Chin Med 2016; 34: 2171–2174. [Google Scholar]

Appendix 3. List of included randomized controlled trials

- 1. Xu MF, X XH, Zhu HX. Effect of needle acupuncture with moxibustion on irritable bowel syndrome patients [Chinese]. Res Integrated Traditional Chinese Western Med 2009; 1: 212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun JH, Wu XL, Xia C, et al. Clinical evaluation of Soothing Gan (肝) and invigorating Pi (脾) acupuncture treatment on diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Chin J Integr Med 2011; 17: 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luo SJ, Long JH, Huang L. Combination of moxibustion with pinaverium bromide for treating pain and diarrhea of irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. J Jingganshan Med College 2008; 15: 39–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu SY. Effect of needle acupuncture on diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome patients [Chinese]. Guangxi J Traditional Chinese Med 2014; 37: 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kong SP, Wang WQ, Xiao N, et al. Clinical research of acupuncture plus ginger-partitioned moxibustion for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox 2014; 33: 895–898. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wei B, Lu WB, Zhang YM, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. J Jinan University (Medical Edition) 2011; 32: 657–659. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu N, Wang J. Chinese research of acupuncture on Shang Juxu for irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Shandong J Chinese Medicine 2013; 32: 183–184. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun YZ, Song J. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture at Jiaji (EX-B2) in treating irritable bowel syndrome [Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox 2015; 34: 856–857. [Google Scholar]