Abstract

Background:

Regorafenib is considered a standard of care as third-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancers (mCRCs).

Materials and Methods:

The study was based on a computerized clinical data form sent to oncologists across the country for entry of anonymized patient data. The data entry form was conceived and generated by the coordinating center's (Tata Memorial Hospital) gastrointestinal medical oncologists and disseminated through personal contacts at academic conferences as well as through E-mail to various oncologists across India.

Results:

A total of 19 physicians contributed data resulting in 80 patients receiving regorafenib who were available for the evaluation of practice patterns. The median age was 55 years (range: 24–75). Majority had received oxaliplatin-based (97.5%), irinotecan-based (87.5%), and targeted therapy (65%), previously. Patients were primarily started on reduced doses of regorafenib upfront (160 mg – 28.8%, 120 mg – 58.8%, and 80 mg – 12.5%). The median duration of treatment (treatment duration) with regorafenib was 3.1 months (range: 0.5–18), while the median progression free survival was 3.48 months (range: 2.6–4.3). Forty-five percent of patients required dose modifications due to toxicities, and the most common were (all grades) hand-foot syndrome (68.8%), fatigue (46.3%), mucositis (37.6%), and diarrhea (31.3%).

Conclusions:

Majority of physicians in this collaborative study from India used a lower dose of regorafenib at the outset in patients with mCRC. Despite a lower dose, there was a significant requirement for dose reduction. Duration of treatment with regorafenib as an efficacy end point in this study is similar to available data from other regions as it is the side effect profile.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, India, REgorafenib in metastatic colorectal cancer - An Indian eXploratory analysis study, regorafenib

Introduction

Regorafenib is considered as standard of care in patients with metastatic colorectal cancers (mCRC) posttreatment with oxaliplatin-based and irinotecan-based regimens. This is based on two seminal trials, Patients with metastatic COloRectal cancer treated with REgorafenib or plaCebo after failure of standard therapy (CORRECT) and Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR), which compared regorafenib with placebo and showed a statistically significant benefit in overall survival (OS).[1,2]

Postpublication of these studies, there have been multiple series from various countries which have shown outcomes which largely matched those seen with the initial studies. A meta-analysis published recently comprising 702 patients and 12 studies confirmed the magnitude of benefits with regorafenib as well as side effect profile as being similar to the phase III data.[3] A majority of these studies have also shown that a major limiting factor with the use of regorafenib has been its toxicity and side effect profile, specifically the degree of hand-foot syndrome (HFS), fatigue, and diarrhea. Small, single-arm studies have suggested that starting regorafenib at lower doses may improve the toxicity profile, while maintaining symptomatic and survival benefit.[4] There is also emerging evidence which shows that the presence of skin rash and hypothyroidism may statistically correlate with improved OS.[5] The conundrum of juggling modest clinical benefits with a troublesome side effect profile with regorafenib in routine clinical practice remains unanswered.

Keeping the above factors in mind, we planned a study with the primary objective of evaluating how clinicians in India used regorafenib in their setting and whether their methods of usage corresponded to available data. Secondary objectives included an assessment of side effect and toxicity patterns with regorafenib, the need for dose modifications, and an assessment of outcomes with regorafenib as reported by clinicians.

Materials and Methods

Clinical record form

A clinical record form for anonymized patient data entry was created by the gastrointestinal (GI) medical oncologists of the coordinating center (Tata Memorial Hospital) based on their estimation of data required for the evaluation of regorafenib in clinical practice. The entry form was divided into five domains:

Demographic details

Information on disease

Prior treatment history

Treatment details with regorafenib

Adverse event profile with regorafenib.

The details of each domain are detailed in the supplementary index 1.

Distribution of clinical record form

The CRF was distributed online for anonymized patient data entry. The form was designed on Google forms (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). Clinicians were identified from a database maintained in the GI medical oncology information system as well as through personal contacts. Individual and group E-mails with a link to the online CRF were sent to these physicians, and they were requested to reply from April 12, 2017, onward to December 31, 2017.

All responses were recorded electronically and translated into a Google spreadsheet, which was used for analysis. In case of missing data, clinicians were requested to supply the same where available by E-mail responses.

Ethics

The data collection and handling was conducted as per the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.[6] It was a retrospective analysis of prospective database, and hence, consent was not taken.

Sample size

Convenience sampling was used for this study as we did not know what the response rates to the study would be. Formal sample size calculations were not performed.

Statistical analysis

Data were converted for entry in SPSS software (IBM) version 21 and used for analysis. Descriptive statistics including median, frequency, and percentage for categorical variables are used. Duration of treatment on regorafenib was calculated from the date of starting treatment with regorafenib to the date of permanent cessation of regorafenib and was labeled as treatment duration (TD), and this was considered as a surrogate for event-free survival. Median progression-free survival was defined as survival from the start of regorafenib to clinicoradiological progression and was calculated using Kaplan–Meier estimates.

Results

Baseline demographic and preclinical characteristics [Table 1]

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and preclinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Number (percentage where feasible) |

|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 55 years (range: 24-75) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (63.8) |

| Female | 29 (36.2) |

| Baseline comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 20 (25) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (17.5) |

| Cardiac dysfunction | 1 (1.3) |

| Pathological details | |

| Degree of differentiation | |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 13 (16.3) |

| Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma | 7 (8.8) |

| Moderately differentiated carcinoma | 35 (43.8) |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 25 (31.3) |

| Signet-ring histology | |

| Yes | 10 (12.5) |

| No | 55 (68.8) |

| Not available | 15 (18.8) |

| Mucinous histology | |

| Yes | 16 (20) |

| No | 52 (65) |

| Not available | 12 (15) |

| Molecular markers | |

| All RAS status | |

| Wild type | 27 (33.8) |

| Mutant | 18 (22.5) |

| Not available | 35 (43.8) |

| BRAF status | |

| Wild type | 0 |

| Mutant | 9 (11.3) |

| Not available | 71 (88.8) |

| MMR protein status | |

| MMR deficient | 4 (5) |

| MMR proficient | 5 (6.3) |

| Not available | 71 (88.8) |

MMR=Mismatch repair, NOS=Not otherwise specified, RAS=RAt Sarcoma virus

A total of 80 patient data were uploaded by clinicians and available for analysis. Median age was 55 years (range: 24–75), and majority were male patients (63.8%).

Pathologically, most patients have moderately differentiated cancers (43.8%), with signet-ring histology being 12.5% and mucinous histology being 20%. RAS (RAt Sarcoma virus) status was reported in 56.3% of patients with more patients having RAS wild-type (33.8%; n = 80) tumors. BRAF status and mismatch repair (MMR) status were determined only in a minority of patients (11.3% for both).

Baseline tumor-related and prior treatment-related details

Common sites of the primary tumor were left sided (nonrectal) (35%) and rectal tumors (35%), with most patients having metastatic disease at initial diagnosis (56.3%). Median lines of previous therapy were two, with 97.5% of patients and 87.5% of patients being previously treated with oxaliplatin-based and irinotecan-based chemotherapeutic regimens. Targeted therapy was offered before regorafenib in 65% of patients [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline tumor-related and prior treatment-related details

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary site of disease | |

| Left sided (nonrectal) | 28 (35) |

| Right sided | 22 (27.5) |

| Rectum | 28 (35) |

| NR | 2 (2.5) |

| Baseline presentation (at initial diagnosis) | |

| Metastatic | 45 (56.3) |

| Nonmetastatic | 35 (43.7) |

| Prior curative intent treatment offered | |

| Yes | 56 (70) |

| No | 24 (30) |

| Prior systemic therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Oxaliplatin-based therapy | 78 (97.5) |

| Irinotecan-based therapy | 70 (87.5) |

| Metronomic therapy | 5 (6.3) |

| Others | 3 (3.8) |

| Targeted therapy | |

| Bevacizumab | 27 (33.8) |

| Anti-EGFR directed therapy | 25 (31.3) |

| Any use of targeted therapy | 52 (65) |

| Prior lines of therapy | |

| Median | 2 |

| Range | 1-4 |

EGFR=Epidermal growth factor receptor, NR=Not reported

Use of regorafenib and response rates

Most clinicians reported starting regorafenib at lower doses than the recommended 160 mg per day dosing (80 mg – 12.5% and 120 mg – 58.8%). While on treatment, 45% of patients required further dose reductions of regorafenib. The most common causes of patients requiring dose modifications were reported as HFS (36.3%), diarrhea (13.8%), skin rash (12.5%), and fatigue (10%). Best responses were reported in 63 patients, with partial responses seen in 10% and stable disease in 27.5% of patients, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Regorafenib use, dosing, and response rates

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Dose of regorafenib started (mg) | |

| 80 | 10 (12.5) |

| 120 | 47 (58.8) |

| 160 | 23 (28.8) |

| Regorafenib dosing during treatment | 3.1 (0.5-18) |

| Requirement of dose reductions | |

| Yes | 36 (45) |

| No | 43 (53.8) |

| NR | 1 (1.3) |

| Cause of dose reduction | |

| HFS | 29 (36.3) |

| Skin rash | 10 (12.5) |

| Mucositis | 6 (7.5) |

| Diarrhea | 11 (13.8) |

| Fatigue | 8 (10) |

| Hypertension | 3 (3.8) |

| Liver dysfunction | 2 (2.5) |

| Myelosuppression | 2 (2.5) |

| Others | 2 (2.5) |

| Response rates | |

| Partial response | 8 (10) |

| Stable disease | 22 (27.5) |

| Progressive disease | 33 (41.3) |

| NR | 17 (21.3) |

| Reasons for cessation of regorafenib (n=72) | |

| Progressive disease | 54 (75) |

| Toxicities | 9 (12.5) |

| Lost to follow-up | 9 (12.5) |

| Offered cancer-directed therapy postregorafenib (n=72) | |

| Yes | 18 (25) |

| No | 54 (75) |

HFS=Hand-foot syndrome, NR=Not reported

Toxicity profile and outcomes with regorafenib

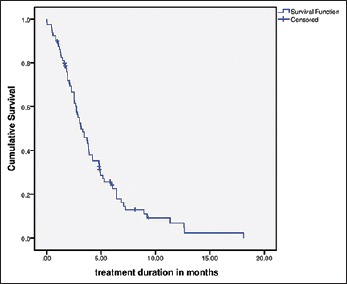

Details of all toxicities reported by clinicians are reported in Table 3 with a comparison of data between the current study and the landmark trials in Table 4.[1,2] At the closure of study, 72 patients (90%) had permanently stopped regorafenib, while the remaining patients were still continuing treatment. The most common cause of cessation of regorafenib was progressive disease (75%). Twenty-five percent of patients were offered further therapy postcessation of regorafenib. The median TD and progression free survival (PFS) with regorafenib were 3.1 months (range: 0.5–18) and 3.48 (2.6–4.3) [Figure 1].

Table 4.

Comparison of toxicity profile across CONCUR, CORRECT, and REMIX

| Toxicities of any grade | CONCUR[2] | CORRECT[1] | REMIX |

|---|---|---|---|

| HFS (%) | 73 | 47 | 69 |

| Skin rash (%) | 8 | 26 | 17.6 |

| Diarrhea (%) | 18 | 34 | 31.3 |

| Mucositis (%) | NR | 27 | 37.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33 | 28 | 27.5 |

| Vomiting (%) | NR | 8 | 5.3 |

| Fatigue (%) | 17 | 47 | 46.3 |

| Liver dysfunction (%) | 24 | 9 | 17.5 |

HFS=Hand-foot syndrome, NR=Not reported, LFT=Liver function test, REMIX: REgorafenib in Metastatic colorectal cancer - an Indian eXploratory analysis, CORRECT=Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with regorafenib or placebo after failure of standard therapy

Figure 1.

Treatment duration in months

Patients were evaluated based on initial dose of regorafenib received (80, 120, or 160 mg). Duration of treatment, requirements for dose reductions, and median PFS in each cohort are detailed in Table 5. There was no statistical difference between the three groups in terms of PFS (P = 0.123).

Table 5.

Performance of different regorafenib doses

| Dose | Requiring dose reduction (%) | Median TD (months) | Median PFS | PFS range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 mg OD (n=10) | 20 | 2.91 | 4.8 | 0.0-11.74 |

| 120 mg OD (n=47) | 61 | 2.53 | 2.56 | 1.94-3.182 |

| 160 mg OD (n=23) | 70 | 3.90 | 4.90 | 3.403-6.387 |

TD=Treatment duration, PFS=Progression free survival

Discussion

Results seen with interventions/drugs in seminal trials form the backbone on which clinical practice is conducted. This comes with the caveats of a well-selected cohort of patients in trials with controlled/negligible comorbidities, intensive monitoring, and funding as opposed to a real-world patient's cohort. Occasionally, clinical practice and small studies may add nuances not seen with and addressed in clinical trials. This appears to be the case with regorafenib.

The current study was an attempt to evaluate the experience with regorafenib in nontrial clinical practice in India, besides obtaining an idea as to its position in the sequencing of treatment when used in mCRC. The study was conceived based on an online platform to facilitate easy entry of data for community- and institution-based oncologists. Despite the limited sample size of the current study, certain generalizations regarding the use of regorafenib by Indian physicians can be made.

The striking feature at baseline is the high incidence of signet-ring histology (12.5%), which is a known poor prognostic factor in CRC. The higher prevalence of signet-ring histology in Indian patients has been previously noted and is consistent with the current study.[7,8,9] A higher incidence of baseline metastatic disease was also seen as compared to previously published data from India (28% vs. 56.3%).[10]

A majority of patients were treated with oxaliplatin-based (97.5%) and irinotecan-based (87.5%) prior chemotherapy as it is considered standard before introducing regorafenib as a treatment modality. A high percentage of patients had previously received targeted therapy, either bevacizumab or cetuximab (65%). Such high rates of receipt of targeted therapy are in discordance with known rates of targeted therapy use in India for other cancers.[11] This is most likely due to a selection bias in that only patients who can afford targeted therapy received regorafenib (monthly cost of regorafenib 160 mg/day in India: US$1160–1600) and also would opt for third-line therapy in colorectal cancers.

The biological rationale of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy postprogression on prior anti-VEGF therapy in mCRC is a largely unexplored arena. A close look at the CORRECT study reveals that 100% of patients had previously received bevacizumab, while only 60% received bevacizumab in the CONCUR study. In the current REgorafenib in Metastatic colorectal cancer - an Indian eXploratory analysis (REMIX) study, only 33.8% of patients received bevacizumab. Whether such lower use of prior bevacizumab resulted in slightly improved PFS in the CONCUR and REMIX studies with regorafenib is a point of debate (3.2 vs. 3.48 vs. 1.9 months). Such hypothesis brings to focus the possibility of using regorafenib earlier in the treatment sequencing of mCRC as it has also been postulated in the REVERCE study with cetuximab.[12]

The median duration (TD) on regorafenib and median PFS were considered by the investigators as the most appropriate measurements of efficacy for a study of this nature. The median PFS on regorafenib in this study was 3.48 months. The efficacy seen with regorafenib in this study corresponds to that seen worldwide (2.71–3.97 months). It is also similar to the efficacy seen in a smaller Indian study previously.[13]

A major focus of the current study was an assessment of the side effect profile reported by clinicians. The most common causes reported as reasons for dose modification were HFS, diarrhea, and rash. Besides HFS, most toxicities in this study appeared similar to the CORRECT study. The CONCUR study in an Asian population [Table 4] also noted a high incidence of HFS (73% vs. 68.8%), suggesting a geographical difference in toxicity profile potentially relating to specific gene polymorphisms. An important practice point we could identify from this survey was that a majority of Indian physicians used a lower dose of regorafenib when initiating treatment. Despite such a significant proportion of clinicians starting at the lower dose of regorafenib, 45% of patients required further dose reduction. Recently published data from the ReDOS study suggest starting patients with an 80 mg daily dose and further escalation based on tolerance.[14] Such an approach actually improved outcomes with maintained quality of life with a lesser incidence of side effects. Whether a similar strategy for dose escalation can be used in Indian patients needs further evaluation considering the early onset and higher incidences of debilitating HFS, which may preclude or prevent dose –escalation on a weekly basis. Dose modifications leading to prolonged exposure of regorafenib may help to improvise outcomes.

The current collaborative study comprises a small cohort of patients with mCRC who have been treated by 19 clinicians with regorafenib across India. It is a true representation of practice patterns employed by clinicians and it is heartening to note that the outcomes are concordant with those seen across the world. The usage of a lower starting dose appears to be common in clinical practice, and there appears to be some evidence to suggest that there is biological plausibility for the same. The small number of patients accrued in the study is also indicative of the small numbers of patients who are feasible for this drug, based on availability and financial constraints. However, multiple caveats exist with respect to the data generated from this study. The data are based on online responses where reporting bias may exist. Follow-up postregorafenib has not been estimated in this study, which means OS data is not available.

Conclusions

Majority of physicians in this collaborative study from India used a lower dose of regorafenib at the outset in patients with mCRC. Despite a lower dose, there was a significant requirement for dose reduction. Duration of treatment with regorafenib as an efficacy end point in this study is similar to available data from other regions as it is the side effect profile. The strategies used in our study and ReDOS may help to improvise outcome by prolonging the exposure to regorafenib.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the patients, whose data were used for the manuscript.

References

- 1.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Qin S, Xu R, Yau TC, Ma B, Pan H, et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:619–29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercier J, Voutsadakis IA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective series of regorafenib for treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:5925–34. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osawa H. Response to regorafenib at an initial dose of 120 mg as salvage therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:365–72. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giampieri R, Prete MD, Prochilo T, Puzzoni M, Pusceddu V, Pani F, et al. Off-target effects and clinical outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving regorafenib: The TRIBUTE analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45703. doi: 10.1038/srep45703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WMA – The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wmadeclaration- of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involvinghuman- subjects/

- 7.Chew MH, Yeo SA, Ng ZP, Lim KH, Koh PK, Ng KH, et al. Critical analysis of mucin and signet ring cell as prognostic factors in an Asian population of 2,764 sporadic colorectal cancers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1221–9. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inamura K, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, Kim SA, Mima K, Sukawa Y, et al. Prognostic significance and molecular features of signet-ring cell and mucinous components in colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1226–35. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamhankar AS, Ingle P, Saklani A. PWE-284 signet ring colorectal carcinoma (SRCC): Do we need to improve the treatment algorithm? Gut. 2015;64(Suppl 1):A336–7. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i12.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil PS, Saklani A, Gambhire P, Mehta S, Engineer R, De’Souza A, et al. Colorectal cancer in India: An audit from a tertiary center in a low prevalence area. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2017;8:484–90. doi: 10.1007/s13193-017-0655-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh J, Gupta S, Desai S, Shet T, Radhakrishnan S, Suryavanshi P, et al. Estrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptor expression in breast tumors of patients, and their usage of HER2-targeted therapy, in a tertiary care centre in India. Indian J Cancer. 2011;48:391–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.92245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shitara K, Yamanaka T, Denda T, Tsuji Y, Shinozaki K, Komatsu Y, et al. Reverce: Randomized phase II study of regorafenib followed by cetuximab versus the reverse sequence for metastatic colorectal cancer patients previously treated with fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4 Suppl):557. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanwar S, Ostwal V, Gupta S, Sirohi B, Toshniwal A, Shetty N, et al. Toxicity and early outcomes of regorafenib in multiply pre-treated metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma-experience from a tertiary cancer centre in India. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:74. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.02.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeting Library | Regorafenib dose Optimization Study (ReDOS): Randomized Phase II trial to Evaluate dosing Strategies for Regorafenib in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC) – An ACCRU Network Study. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/155600/abstract .