Abstract

Background.

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) adolescents and young adults experience elevated rates of alcohol and drug use; it is therefore important to identify protective factors that decrease risk for substance use in this population. This study examined whether involvement in a romantic relationship, a well-established protective factor against heavy drinking and drug use among heterosexual adults, is also protective for SGM youth.

Methods.

This study used eight waves of data provided by a community sample of 248 racially diverse SGM youth (ages 16 – 20 years at baseline). Multilevel structural equation models were used to assess within-person associations between relationship involvement and use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. Age, gender, and sexual identity were tested as moderators.

Results.

Romantic involvement was associated with less drinking for all participants (Rate Ratio = 0.64) and less illicit drug use for gay and lesbian participants (Odds Ratio =0.56). However, participants reported smoking 26% more cigarettes when romantically involved. Further, among bisexuals, romantic involvement was associated with increased marijuana (Rate Ratio = 2.31) and other illicit drug use (Odds Ratio =2.39).

Conclusions.

Study findings indicate some protective effects of relationship involvement against substance use among SGM youth, particularly with respect to alcohol and illicit drugs other than marijuana. However, dating may promote smoking in all SGM youth and drug use in those who identify as bisexual. The demographic differences observed in the effects of romantic involvement highlight the importance of attending to differences among SGM youth in research, theory, and substance use reduction efforts.

1. Introduction

Substance use and heavy drinking represent a significant public health problem, particularly during adolescence and young adulthood (Bachman et al., 2002; Johnston, 2010). Among young people, sexual and gender minorities (SGM) are at 2–3 times higher risk for cigarette, alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use than heterosexuals (Marshal et al., 2008). It is therefore important to identify factors that may protect young SGM from substance use.

One well-established protective factor against problematic substance use among heterosexual adults is marriage. Longitudinal studies consistently show that entry into marriage is followed by reduced binge drinking and drug use (Duncan et al., 2006; Fleming et al., 2010; Staff et al., 2010). According to social control theories, spouses monitor one another, discouraging risky behaviors such as heavy drinking, smoking, and drug use (Lewis and Butterfield, 2007). The internalization of behavioral norms for the social role of a spouse may also reduce substance use, which is often viewed as more appropriate for single individuals (Umberson, 1987). Further, marriage is associated with tangible legal and financial benefits (Waite and Gallagher, 2000) and fulfills individuals’ needs for social connection, emotional support, and intimacy (House et al., 1988). Therefore, it may also reduce substance use by decreasing financial stress, loneliness, and isolation, which many individuals cope with through substance use.

1.1. Relationship Involvement and Substance Use among Adolescents and Young Adults

It remains unclear whether the “marriage benefit” to substance use generalizes to the dating relationships of young people. Young romantic partners may not exert social control over each other or monitor their romantic partner’s behavior, and the social pressure to refrain from risky behaviors when married is not typically present in young dating relationships. In fact, involvement in dating during adolescence has been linked with increases in other high-risk behaviors, including delinquency (Cui et al., 2012; Joyner and Udry, 2000) and externalizing behaviors (Furman and Collibee, 2014; van Dulman et al., 2008). Further, the non-marital romantic relationships of youth generally do not provide legal or financial benefits that might alleviate stressors associated with substance use. To the contrary, among adolescents, romantic involvement has been associated with depression (Davila et al., 2004), possibly due to the stresses of dating that teens lack the emotional resources to handle (Davila, 2008). Alternatively, being in an intimate relationship may discourage substance use among young people, partly by limiting engagement in the single “hook-up” culture, where heavy drinking and drug use is common (e.g., Owen et al., 2010). Romantic involvement may also provide youth with a sense of accomplishment and social identity (Montgomery, 2005), along with emotional intimacy not offered by other social partners. Both factors may reduce youth’s use of substances to cope with loneliness or negative affect.

Research examining the association between dating relationships and substance use among young people is fairly limited and inconsistent. Cross-sectional studies of young adults have found that, compared to those who are single, those in committed relationships report less alcohol consumption (Braithwaite et al., 2010; Whitton et al., 2013) but do not differ in use of tobacco or illicit drugs (Braithwaite et al., 2010; Simon and Barrett, 2010). Some longitudinal research on young adults has indicated that substance use declines when individuals enter dating (Furman and Collibee, 2014) and nonmarital cohabiting relationships (Duncan et al., 2006; Staff et al., 2010), though effects are not as consistent or strong as for marriage. However, another study found that entry into a relationship between ages 18 and 20 was not associated with reduced heavy drinking or marijuana use and was associated with increases in smoking (Fleming et al., 2010). Further, romantic involvement has been associated with greater alcohol (Davies and Windle, 2000; Miller et al., 2009) and substance use (Furman and Collibee, 2014) in adolescents (< 18 years).

1.2. Relationship Involvement and Substance Use among Sexual and Gender Minorities

It also is unclear whether romantic involvement has effects on substance use among SGM, particularly youth. Among adults, same-sex romantic relationships are exceedingly similar to different-sex relationships in relationship quality (e.g., Kurdek, 2005) and associations between relationship functioning and partners’ mental health (Whitton and Kuryluk, 2014). Sexual minority and heterosexual adults report similar efforts to promote healthy behaviors in their romantic partners, including discouraging heavy substance use (Reczek and Umberson, 2012), suggesting the “marriage benefit” observed in heterosexual adults is likely to generalize to SGM adults. It is also possible that the increased risk of substance use associated with heterosexual romantic involvement during adolescence will generalize to SGM. In fact, this effect might be more pronounced among SGM youth, because dating may increase stress by activating any internal conflicts about sexuality and may raise risk for discrimination and family rejection by revealing their same-sex attractions. Further, involvement with a same-sex partner may promote engagement in SGM communities, which often have tolerant social norms regarding substance use (Cochran et al., 2012; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008). Alternately, SGM youth may benefit more psychologically than heterosexual youth do from having a romantic partner, who may provide social support lacking from their parents and schoolmates (Katz-Wise and Hyde, 2012; Ryan et al., 2009). Similarly, increased affiliation with the LGBT community may buffer the effects of minority stress (Johns et al., 2013), thereby reducing substance use as a coping method. Unfortunately, we were unable to locate any studies investigating associations between relationship involvement and substance use in SGM.

1.3. Potential Moderators of Relationship Involvement Effects on Substance Use

Although often treated as a homogenous group, SGM young people are diverse in age, gender, and sexual identity (i.e., self-identified sexual orientation). As we seek to understand how relationship involvement may affect substance use among young SGM, we must explore potential differences between demographic groups. First, effects of dating on substance use among SGM youth may show developmental differences across adolescence and young adulthood. The normative trajectory model theorizes that romantic involvement undermines social-emotional health during adolescence when it is non-normative, but promotes wellbeing beginning in young adulthood when it is normative (Connolly et al., 2013) and represents a salient developmental task (Furman and Collibee, 2014). Consistent with this theory, romantic involvement was associated with more substance use in middle adolescence but less substance use in young adulthood in a predominantly heterosexual sample (Furman and Collibee, 2014).

Effects of romantic involvement on young SGM substance use may also vary by gender. Findings from heterosexual samples are highly inconsistent: Among young adults, some studies have found no gender differences in the beneficial effects of romantic involvement on substance use (Fleming et al., 2010; Whitton et al., 2013) whereas others found stronger effects for women than men on binge drinking (Duncan et al., 2006) and substance use problems (Simon and Barrett, 2010). Among heterosexual adolescents, some have speculated that dating may promote substance use more in female than male adolescents, because all youth are more likely to be introduced to substance use by a male (Miller et al., 2009). However, most studies find no gender differences in effects of romantic involvement on adolescent substance use (Beckmeyer, 2015; Furman and Collibee, 2014; Joyner and Udry, 2000). Further, this theory assumes adolescents date someone of a different gender, often not the case for SGM youth.

Specific sexual identities may also influence how romantic involvement affects substance use. Although dating is associated with better psychological health among gay and lesbian individuals, among bisexuals it is associated with greater risk for anxiety disorders (Feinstein et al., 2016) and more psychological distress (Whitton et al., 2018). These differences may be attributable to unique stressors bisexuals face when involved in romantic relationships, including invalidation of their bisexual identity by others who assume they are lesbian/gay or heterosexual based on their current partner’s gender (Dyar et al., 2014) and pressure from non-bisexual partners to change their sexual identity (Bostwick and Hequembourg, 2014). The psychological distress resulting from such experiences might raise risk for substance use among bisexuals who enter romantic relationships. Exploring this possibility is important, as bisexual youth use cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs at markedly higher rates than heterosexual, gay, and lesbian youth (Marshal et al., 2008).

1.4. The Current Study

In the current study, we aimed to examine how relationship involvement influences substance use among SGM youth. Using multiwave longitudinal data from a large and diverse sample, we assessed whether, within-persons, relationship involvement is associated with use of cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. That is, do SGM youth tend to use these substances less (or more) often at times when they are in a relationship versus when they are single? Further, we examined whether these effects differ by age, gender, and sexual identity.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

Participants were 248 sexual and gender minority youth from Chicago who participated in Project Q2, an IRB-approved longitudinal study of LGBT youth. Project Q2 employed an accelerated longitudinal design in which participants who varied in age at baseline (from 16–20 years; collected from 2007–2009) provided eight waves of data over 5 years (baseline and 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, 42-, 48-, and 60-month follow-up). Retention at each wave ranged from 80–90%. See Mustanski et al. (2010, 2016) for details about Project Q2. These analyses used data from all waves except 18-month follow-up, when relationship involvement was not assessed. Verifications during follow-ups revealed that 13 participants misreported their age at baseline; data these participants provided when outside the study age range were removed (22 timepoints). Participants were paid $25-$50 per wave. See Table 1 for sample demographics at baseline.

Table 1.

Description of Demographics at Baseline (N=248)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | (18.8, 1.32) |

| Birth Sex | |

| Male | 118 (47.6) |

| Female | 130 (52.4) |

| Gender Identity | |

| Cisgender Men | 107 (43.1) |

| Cisgender Women | 121 (48.8) |

| Transgender | 20 (8.1) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Gay | 85 (34.3) |

| Lesbian | 69 (27.8) |

| Bisexual | 70 (28.2) |

| Questioning/Unsure | 24 (9.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 35 (14.1) |

| Black/African American | 139 (56.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 30 (12.1) |

| Other | 44 (17.7) |

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics.

At baseline, participant age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity were assessed. Age at each wave was calculated using birth date and assessment date.

The following measures were collected at each wave:

2.2.2. Current Relationship Involvement.

Participants were asked about their current and recent relationships (past 6 months). Those who reported a current romantic relationship at a given wave were coded 1, others as 0.

2.2.3. Cigarette use.

Participants were asked, “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” Those who said yes were asked, “How many cigarettes a day do you smoke?” (open-ended). This variable represents the current number of cigarettes smoked per day (non-smokers coded as 0).

2.2.4. Alcohol use.

Participants were asked, “In the last 6 months, how many days did you drink alcohol?” and quantity “Think of all the times you have had a drink during the last 6 months. How many drinks did you usually have each time?” Quantity and frequency were multiplied to create an index of alcohol use (Bartholow and Heinz, 2006; Greenfield, 2000), or the number of alcoholic drinks consumed over the past 6 months.

2.2.5. Marijuana use.

Participants’ open-ended responses to the question, “In the last 6 months, how many times did you use marijuana?” were used as an index of marijuana use. This variable represents number of times the participant used marijuana in the past 6 months.

2.2.6. Other Illicit drug use.

Participants were asked, “In the last 6 months, did you use [illicit drug]?” Illicit drugs included cocaine, methamphetamines, and club drugs (e.g., ecstasy, ketamine, GHB). Because endorsement was low across waves (0.0%−2.0% methamphetamines, 3.8–10.0% cocaine, and 5.8–10.8% club drugs), we created a dichotomous variable indicating any use of illicit drugs other than marijuana in the past 6 months (9.5–15.6% of participants per wave).

2.3. Analyses

Mplus Version 7 with robust maximum likelihood estimation was used to conduct analyses (Muthén and Muthén, 2012). 10.7% of data were missing and were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML), which was appropriate given preliminary analyses indicating data was missing at random (i.e., missingness not predicted by available variables). To test hypotheses, we used multilevel modeling: Repeated measures (Level 1) were nested within individuals (Level 2). To assess within-person associations between relationship involvement and each substance use outcome (i.e., cigarette, alcohol, marijuana, other illicit drug use), the given substance use variable at each time point was predicted by relationship involvement at that time point. This Level 1 association was modeled as random (i.e., free to differ between participants) to allow for tests of moderation by demographic characteristics. Age (grand mean centered) at each time point was included at Level 1, and age, gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity were included as controls at Level 2. We used negative binomial distributions to model cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use because these variables were overdispersed (standard deviation > mean; see Table 2); though we also considered a zero-inflated model of cigarette use, Akaike and Bayesian Information Criterion (AIC and BIC) values were lower for the negative binomial model (ΔAIC = −28.84; ΔBIC = −97.80), suggesting it was more parsimonious and had a better fit to the data than a zero-inflated model (Raftery, 1995). A Bernoulli distribution was used to model other illicit drug use (a dichotomous variable).

Table 2.

Descriptives for Major Study Variables

| Variable | ICC | Mean (SD) | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .26 | 21.07 (2.37) | 20.88 | 16–27 |

| Relationship Involvement | .19 | .53 (.50) | 1.00 | 0–1 |

| Cigarette Use | - | 2.54 (4.13) | .00 | 0–17 |

| Alcohol Use | - | 57.10 (101.16) | 15.00 | 0–540 |

| Marijuana Use | - | 35.23 (59.63) | 2.00 | 0–191 |

| Illicit Drug Use | - | .12 (.32) | .00 | 0–1 |

ICC = intra-class correlation. ICCs are not presented for count or binary variables. Descriptive statistics are based on Winsorized count variables.

Next, for each substance use variable, we ran three additional models to test for moderation of the within-person association between romantic involvement and substance use by: 1) age, 2) sexual identity, and 3) gender. In the age moderated models, a latent variable interaction was added at Level 1 to model the interaction between age and relationship involvement in predicting substance use at each wave (Preacher et al., 2016). In the sexual identity moderated models, sexual identity (lesbian/gay [coded 0]; bisexual [coded 1]) was added to Level 2 as a predictor of the Level 1 association between relationship status and substance use (i.e., cross-level interaction; Aguinis et al, 2013); the 24 participants who identified as unsure or questioning were excluded from these models due to their small number (included in all other models). In the gender moderated models, gender (cisgender men [coded 0]; cisgender women [coded 1]) was added as a Level 2 predictor of the Level 1 association between relationship involvement and substance use; the 20 transgender participants were excluded from these models (but included in all others).

3. Results

Table 2 includes intra-class correlations (ICCs) for binary and continuous variables and means, standard deviations, and medians for all variables. To reduce the impact of extreme outliers in alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use, these variables were Winsorized (Yang et al., 2011): cigarette use at 3 standard deviations above the mean (17.27) and alcohol and marijuana use at the 95th percentile (190 for marijuana; 90 for alcohol) because outliers remained when using 3 standard deviations above the mean.

3.1. Cigarette Use

In the unmoderated model for cigarette use (Table 3), there was a significant average within-person effect of relationship involvement on cigarette use. Participants smoked 1.26 times more cigarettes per day at waves when they were currently in a relationship than at waves when they were single. Despite significant variance in this within-person association across participants, it was not moderated by age, gender, or sexual identity.

Table 3.

Cigarette Use Models

| Model | Effect | B | RR | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmoderated | Slope (relationship inv. → cigarette use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | .23 | 1.26 | .07 | 3.40 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .30 | .04 | 7.75 | < .001 | ||

| Gender Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → cigarette use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.08 | .92 | .09 | −.92 | .36 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .43 | .07 | 6.52 | < .001 | ||

| Gender → Slope | −.23 | .14 | −1.62 | .11 | ||

| Sexual Identity Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → cigarette use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | .22 | 1.25 | .27 | .82 | .41 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .56 | .10 | 5.49 | < .001 | ||

| Sexual Identity → Slope | .05 | .24 | .20 | .84 | ||

| Age Moderated | Relationship Involvement | .04 | 1.04 | .14 | .29 | .77 |

| Age | −.02 | .98 | .04 | −.56 | .58 | |

| Relationship Inv.*Age | −.01 | .99 | .04 | −.35 | .72 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age at the within-level and age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the between-persons level. Dichotomous variable coding: relationship involvement (not in a relationship = 0; in a relationship = 1), gender (cisgender women = 0; cisgender men = 1), sexual identity (lesbian/gay = 0; bisexual = 1). RR = rate ratio; relationship inv. = relationship involvement).

3.2. Alcohol Use

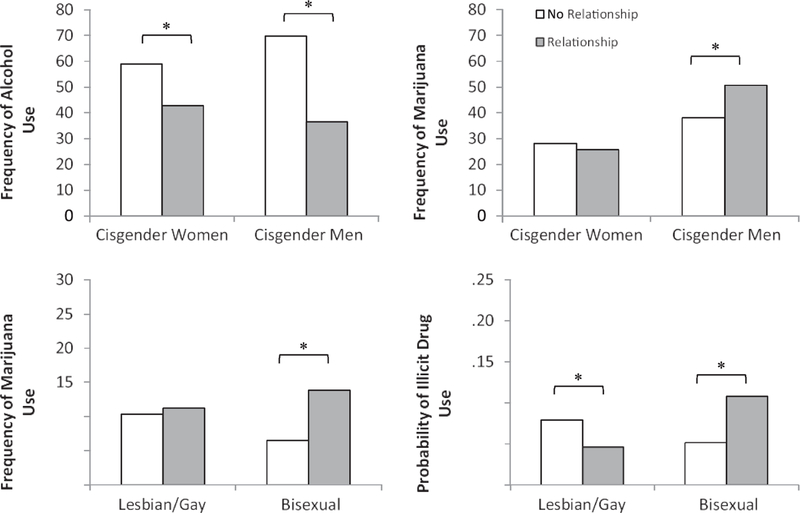

There was a significant average within-person effect of relationship involvement on alcohol use(see unmoderated model, Table 4). At waves when they were romantically involved, youth reported consuming 36% fewer alcoholic drinks in the past 6 months than at waves when they were single. Age and sexual identity did not moderate this association, but gender did (see Figure 1). Simple rate ratios indicated romantic involvement was associated with less alcohol use for both groups, but this effect was stronger for cisgender men (b = −.65, SE = .01, z = −66.43, p < .001; RR = .52) than cisgender women (b = −.32, SE = .01, z = −35.62, p < .001; RR = .73).

Table 4.

Alcohol Use Models

| Model | Effect | b | RR | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmoderated | Slope (relationship inv. → alcohol use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.44 | .64 | .02 | −22.02 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .04 | .01 | 3.09 | .002 | ||

| Gender Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → alcohol use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.32 | .73 | .01 | −35.62 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .004 | .002 | 2.17 | .03 | ||

| Gender → Slope | −.33 | .01 | −28.78 | < .001 | ||

| Sexual Identity Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → alcohol use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.12 | .89 | .02 | −4.87 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .03 | .01 | 6.43 | < .001 | ||

| Sexual Identity → Slope | −.01 | .04 | −.12 | .91 | ||

| Age Moderated | Relationship Involvement | −.07 | .93 | .09 | −.76 | .44 |

| Age | .05 | 1.05 | .02 | 2.25 | .02 | |

| Relationship Inv.*Age | −.04 | .96 | .04 | −.99 | .32 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age at the within-level and age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the between-persons level. Dichotomous variable coding: relationship involvement (not in a relationship = 0; in a relationship = 1), gender (cisgender women = 0; cisgender men = 1), sexual identity (lesbian/gay = 0; bisexual = 1). RR = rate ratio; relationship inv. = relationship involvement).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted frequencies of alcohol and marijuana use and probability of illicit drug use for participants in relationships and not in relationships separately by gender identity and sexual identity. Estimates are adjusted for age at the within-person level and age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the be- tween-person level. *p < .05.

3.3. Marijuana Use

In the unmoderated model(Table 5), the average within-person effect of relationship involvement on marijuana use was not significant. This effect was moderated by gender and sexual identity, but not age (see Figure 1). Simple rate ratios indicated that, within-individuals, relationship involvement was not associated with marijuana use for lesbian/gay individuals (b = .08, SE = .06, z = 1.27, p = .20; RR = 1.08) or cisgender women (b = −.09, SE = .14, z = −.66, p = .51; RR = .91). However, at waves when bisexual individuals (b = .84, SE = .05, z = 18.09, p < .001; RR = 2.31) and cisgender men (b = .29, SE = .15, z = 1.95, p = .05; RR = 1.34) reported current relationship involvement, they reported more frequent past 6 month marijuana use than at waves when they were single.

Table 5.

Marijuana Use Models

| Model | Effect | b | RR | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmoderated | Slope (relationship inv. → marijuana use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | .04 | 1.04 | .12 | .34 | .74 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .41 | .21 | 1.95 | .05 | ||

| Gender Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → marijuana use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.09 | .91 | .14 | −.66 | .51 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .69 | .12 | 5.70 | < .001 | ||

| Gender → Slope | .38 | .19 | 2.03 | .04 | ||

| Sexual Identity Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → marijuana use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | .08 | 1.08 | .06 | 1.27 | .20 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .15 | .03 | 5.60 | < .001 | ||

| Sexual Identity → Slope | .07 | 10.83 | < .001 | |||

| Age Moderated | Relationship Involvement | .12 | 1.13 | .20 | .60 | .55 |

| Age | .001 | 1.00 | .10 | .004 | 1.00 | |

| Relationship Inv.*Age | .04 | 1.04 | .11 | .36 | .72 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age at the within-level and age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the between-persons level. Dichotomous variable coding: relationship involvement (not in a relationship = 0; in a relationship = 1), gender (cisgender women = 0; cisgender men = 1), sexual identity (lesbian/gay = 0; bisexual = 1). RR = rate ratio; relationship inv. = relationship involvement).

3.4. Other Illicit Drug Use

There was a significant negative within-person effect of relationship involvement on use of illicit drugs other than marijuana (see unmoderated model, Table 6). At waves when participants reported relationship involvement, they were 27% less likely to have used other illicit drugs in the preceding 6 months than at waves when they were single (OR = .73). This within-person association was not moderated by age or gender, but was moderated by sexual identity. Simple odds ratios indicated that current relationship involvement was associated with lower likelihood of recent illicit drug use for lesbian/gay individuals (b = −.58, SE = .09, z = −6.29, p < .001; OR = .56) but with a higher likelihood of recent illicit drug use for bisexuals (b = .87, SE = .13, z = 6.82, p < .001; OR = 2.39). Lesbian/gay individuals were 44% less likely to have recently used other illicit drugs during waves when they were in relationships than when they were single, whereas bisexual individuals were 2.39 times more likely to have used these drugs during waves when they were in relationships than when they were single (Figure 1).

Table 6.

Illicit Drug Use Models

| Model | Effect | b | OR | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmoderated | Slope (relationship inv. → drug use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.31 | .73 | .05 | −5.58 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .23 | .07 | 3.52 | < .001 | ||

| Gender Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → drug use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.91 | .40 | .14 | −6.75 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .42 | .06 | 6.65 | < .001 | ||

| Gender → Slope | .19 | .17 | 1.10 | .27 | ||

| Sexual Identity Moderated | Slope (relationship inv. → drug use) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.58 | .56 | .09 | −6.29 | < .001 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .44 | .06 | 7.01 | < .001 | ||

| Sexual Identity → Slope | 1.45 | .15 | 9.67 | < .001 | ||

| Age Moderated | Relationship Involvement | .04 | 1.04 | .25 | .15 | .88 |

| Age | .06 | 1.06 | .05 | 1.20 | .23 | |

| Relationship Inv.*Age | −.05 | .95 | .09 | −.57 | .56 |

Note. All coefficients were estimated controlling for age at the within-level and age, gender, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity at the between-persons level. Dichotomous variable coding: relationship involvement (not in a relationship = 0; in a relationship = 1), gender (cisgender women = 0; cisgender men = 1), sexual identity (lesbian/gay = 0; bisexual = 1). OR = odds ratio; relationship inv. = relationship involvement).

4. Discussion

In the first study to explore how romantic relationship involvement influences the substance use of young SGM, we used multiwave longitudinal data to assess whether young SGM used less (or more) alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit drugs when romantically partnered than when single. In contrast to the normative trajectory model, which suggests that romantic involvement may promote risky behavior in adolescence but inhibit it in young adulthood (Connolly et al., 2013), we found no evidence of developmental differences in the within-person association between romantic involvement and SGM substance use across the ages16–26. Rather, findings suggested that the effects of romantic involvement among SGM youth differ across substances and demographic subgroups.

Relationship involvement demonstrated the most consistent positive effects on alcohol use, with participants reporting 36% less recent alcohol use when in a relationship than when single. Though this effect was stronger for men than women, it was present across gender, age and sexual identity. Echoing evidence that entering a relationship reduces drinking among heterosexual young adults (Duncan et al., 2006; Furman and Collibee, 2014; Staff et al., 2010), this finding suggests that romantic involvement may represent a broad protective factor against alcohol use among SGM youth. Similarly, romantic involvement had a protective effect against use of illicit drugs other than marijuana for participants who identified as gay/lesbian (but not bisexual), reducing their chances of having recently used by 78%. Perhaps by finding a partner, young SGM escape norms of heavy drinking and drug use in the bar/party scene, a common forum for meeting potential romantic or sexual partners (Claxton et al., 2015; Owen et al., 2010).

In contrast to its positive effects on alcohol and other illicit drug use, dating does not appear to protect SGM against marijuana use. In fact, romantic involvement was not associated with marijuana use for gay/lesbian youth or cisgender women and was associated with increased recent use among cisgender men and bisexuals. These findings add to a growing literature, suggesting that the marriage benefit to marijuana use does not extend to non-marital different-sex relationships of young adults (Duncan et al., 2006; Fleming et al., 2010). Further, they suggest dating may be a risk factor for marijuana use among young SGM men. This was surprising because in past research, there have generally been no gender differences (Fleming et al., 2010; Staff et al., 2010), and any evidence of romantic involvement increasing marijuana use has been limited to early and middle adolescence (Beckmeyer, 2015; Furman and Collibee, 2014). The positive association between romantic involvement and marijuana use may persist into young adulthood among male SGM partly because substance use declines less with age among SGMs than in heterosexuals (Green and Feinstein, 2012). Romantic involvement may also affect marijuana use differently for young male SGM than for their heterosexual counterparts due to differences in partner gender (male partners may smoke more marijuana than heterosexual female partners) or because it increases exposure to SGM communities accepting of marijuana use (Cochran et al., 2012).

Romantic involvement was associated with increased drug use for bisexuals. Bisexuals reported 1.34 times more recent marijuana use and were 2.39 times more likely to have recently used other illicit drugs at waves when romantically partnered than when single. These findings add to mounting evidence that the experiences of bisexuals differ markedly from those of other SGM. In addition to being at higher risk for mental health issues (Ross et al., 2017) and substance use (Marshal et al., 2008), bisexuals may not benefit from romantic relationships in the ways that gay, lesbian, and heterosexual young adults do. Together with other findings from this sample indicating that bisexuals report greater psychological distress when romantically involved than when single (Author citation), the current findings suggest that any benefits of dating may be outweighed by the anti-bisexual stigma bisexuals can face from straight and lesbian or gay partners (Bostwick and Hequembourg, 2014; Dyar et al., 2014).

Romantic involvement also increased tobacco use across all demographic groups. On average, SGM youth smoked 26% more daily cigarettes when in a relationship than when single. Although this finding contradicts some earlier evidence that cohabitation, engagement, and marriage all reduce cigarette use among young adults (Staff et al., 2010), it is consistent with other studies documenting increased smoking in young adults who enter a romantic relationship (Fleming et al., 2010) or first marriage (women only; Duncan et al., 2006). It is possible these effects are driven by youth entering relationships with partners who smoke; same- and different-sex partners can promote unhealthy habits in each other (Reczek and Umberson, 2012) and teens who date a smoker are more likely to start smoking (Kennedy et al., 2011). Such socialization effects may be particularly present in LGBT communities, where smoking is more common and often perceived as a way to form connections with other SGM youth (National LGBTQ Young Adult Tobacco Project, 2010). Because we did not assess partner tobacco use, future research is needed to explore this possibility.

Conclusions should be drawn keeping study limitations in mind. First, because we did not have information on length of participants’ current relationships, it is possible that some of the alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use reported occurred prior to the relationship. Second, there were too few transgender individuals to explore potential differences from cisgender individuals, and we did not capture non-binary gender identities. Future research should explore how relationship involvement is associated with substance use across multiple gender and sexual identities, particularly considering the increasing number of LGBT people who identify as non-binary or transgender (Richards et al., 2016) and with sexual identities other than gay/lesbian and bisexual (e.g., pansexual, queer, asexual). Due to small numbers of participants with some racial/ethnic identities (e.g., White n = 35; Latino n = 30), we were unable to test for racial differences in associations; this is an important area for future study. Because we did not collect detailed data on partners or relationships, we could not assess whether findings were influenced by partner gender, gender composition of the relationship (same- vs. different-sex), partner’s substance use, or characteristics of the relationship (e.g., commitment, quality). Future research should also account for relationship commitment, given evidence that serious relationships, but not casual or group dating, increase adolescent substance use (Beckmeyer, 2015).

5. Conclusions

This study provides novel evidence to support some protective effects of relationship involvement against substance use among young SGM. Being in a romantic relationship appears to reduce drinking among all SGM youth, and reduce use of drugs other than marijuana among those who identify as gay or lesbian. Together with evidence that romantic involvement has psychological benefits in this population, reducing distress associated with victimization they experience related to their minority sexual identity (Whitton et al., 2018), these results support initiatives to promote healthy relationships among SGM youth. Efforts to encourage dating among SGM (e.g., through planned LGBT-focused social events), and to teach healthy relationship skills (Mustanski et al., 2015), may ultimately help reduce the mental health and substance use disparities they face. Such efforts must, however, keep in mind that romantic involvement may raise risk for smoking among all young SGM, as well as for drug use among bisexuals and marijuana use among SGM men. These findings speak to the potential value of anti-tobacco campaigns targeting smoking in LGBT communities and of initiatives to reduce the stigmatization of bisexuality.

Contributor Information

Sarah W. Whitton, University of Cincinnati, 4150G Edwards Center I, Cincinnati, OH 5221-0376.

Christina Dyar, University of Cincinnati, 4150G Edwards Center I, Cincinnati, OH 5221-0376, dyar.christina@gmail.com.

Michael E. Newcomb, Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 625 N Michigan Ave Suite 14-061. Chicago, IL 60611, newcomb@northwestern.edu

Brian Mustanski, Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 625 N Michigan Ave Suite 14-061. Chicago, IL 60611, brian@northwestern.edu.

References

- Aguinis H, Gottfredson RK, Culpepper SA, 2013. Best-practice recommendations for estimating cross-level interaction effects using multilevel modeling. J Management, 39, 1490–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman J, O’Malley P, Schulenberg J, Johnston L, Bryant A, Merline A, 2002. Why substance use declines in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BD, Heinz A, 2006. Alcohol and aggression without consumption. Alcohol cues, aggressive thoughts, and hostile perception bias. Psychol. Sci 17, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmeyer JJ, 2015. Comparing the associations between three types of adolescents’ romantic involvement and their engagement in substance use. J. Adolesc 42, 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hequembourg A, 2014. ‘Just a little hint’: bisexual-specific microaggressions and their connection to epistemic injustices. Cult. Health Sex 16, 488–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, Fincham FD, 2010. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Claxton SE, DeLuca HK, van Dulmen MH, 2015. The association between alcohol use and engagement in casual sexual relationships and experiences: A meta-analytic review of non-experimental studies. Arch. Sex. Behav 44, 837–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Grella CE, Mays VM, 2012. Do substance use norms and perceived drug availability mediate sexual orientation differences in patterns of substance use? Results from the California Quality of Life Survey II. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 73, 675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Nguyen HN, Pepler D, Craig W, Jiang D, 2013. Developmental trajectories of romantic stages and associations with problem behaviours during adolescence. J. Adolesc 36, 1013–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M, 2000. Middle adolescents’ dating pathways and psychosocial adjustment. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 90–118.

- Davila J, 2008. Depressive symptoms and adolescent romance: Theory, research, and implications. Child Devel. Perspectives 2, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Steinberg SJ, Kachadourian L, Cobb R, Fincham F, 2004. Romantic involvement and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence: The role of preoccupied relational style. Personal Relationships 11, 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Wilkerson B, England P, 2006. Cleaning up their act: The effects of marriage and cohabitation on licit and illicit drug use. Demography 43, 691–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, London B, 2014. Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Latack JA, Bhatia V, Davila J, Eaton NR, 2016. Romantic relationship involvement as a minority stress buffer in gay/lesbian versus bisexual individuals. J. Gay Lesbian Mental Health 20, 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Oesterle S, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF, 2010. Romantic elationship status changes and substance use among 18-to 20-year-olds. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 71, 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Collibee C, 2014. A matter of timing: Developmental theories of romantic involvement and psychosocial adjustment. Dev. Psychopathol 26, 1149–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KE, Feinstein BA, 2012. Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: an update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav 26, 265–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, 2000. Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: experience with graduated frequencies. J Subst. Abuse 12, 33–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K, 2008. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: Results from a prospective study. Dev. Psychol 44, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR, 1988. Structures and processes of social support. Annu. Rev. Sociol 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Pingel ES, Youatt EJ, Soler JH, McClelland SI, Bauermeister JA, 2013. LGBT community, social network characteristics, and smoking behaviors in young sexual minority women. Am. J. Community Psychol 52, 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, 2010. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2008: Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50 DIANe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Udry JR, 2000. You don’t bring me anything but down: Adolescent romance and depression. J. Health Soc. Behav 41, 369–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Hyde JS, 2012. Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Sex. Res 49, 142–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Tucker JS, Pollard MS, Go M-H, Green HD, 2011. Adolescent romantic relationships and change in smoking status. Addict. Behav 36, 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, 2005. What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 14, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Butterfield RM, 2007. Social Control in Marital Relationships: Effect of One’s Partner on Health Behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol 37, 298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Bukstein OG, Morse JQ, 2008. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 103, 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Lansford JE, Costanzo P, Malone PS, Golonka M, Killeya-Jones LA, 2009. Early adolescent romantic partner status, peer standing, and problem behaviors. J. Early Adolesc 29, 839–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MJ, 2005. Psychosocial intimacy and identity: From early adolescence to emerging adulthood. J. Adolesc. Res 20, 346–374. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, Puckett JA, 2016. The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. Am. J. Public Health 106, 527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Emerson EM, 2010. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am. J. Public Health 100, 2426–2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Greene GJ, Ryan D, Whitton SW, 2015. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of an online sexual health promotion program for LGBT youth: the Queer Sex Ed intervention. J. Sex. Res 52, 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2012. Mplus User’s Guide 7ed. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- National LGBTQ Young Adult Tobacco Project, 2010. Coming out about smoking

- Owen JJ, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Fincham FD, 2010. “Hooking up” among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Arch. Sex. Behav 39, 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, 2016. Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychol. Methods 21, 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C, Umberson D, 2012. Gender, health behavior, and intimate relationships: Lesbian, gay, and straight contexts. Soc. Sci. Med 74, 1783–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards C, Bouman WP, Seal L, Barker MJ, Nieder TO, T’Sjoen G, 2016. Non-binary or genderqueer genders. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 28, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Salway T, Tarasoff LA, MacKay JM, Hawkins BW, Fehr CP, 2017. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Among Bisexual People Compared to Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex. Res, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J, 2009. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 123, 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE, 2010. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? J. Health Soc. Behav 51, 168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Maggs JL, Johnston LD, 2010. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Devel. Psychopathol 22, 917–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M, 2000. The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially Doubleday, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Dyar C, Newcomb M, Mustanski B, 2018. Romantic Involvement: A Protective Factor for Psychological Health in Racially-Diverse Young Sexual Minorities. J. Abnorm. Psychol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whitton SW, Kuryluk AD, 2014. Associations between relationship quality and depressive symptoms in same-sex couples. J. Fam. Psychol 28, 571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Weitbrecht EM, Kuryluk AD, Bruner MR, 2013. Committed dating relationships and mental health among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 61, 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Xie M, Goh TN, 2011. Outlier identification and robust parameter estimation in a zero-inflated Poisson model. J. Applied Statistics 38, 421–430. [Google Scholar]