Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS:

To evaluate the refractive status, axial length, and prevalence of amblyopia among Saudi children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (UCNLDO) compared to the unaffected fellow eye.

METHODS:

A retrospective chart review was performed for children with UCNLDO at two eye institutes in Eastern Saudi Arabia from 2009 to 2015. The outcomes of syringing determined UNCLDO. The risk factors for amblyopia were defined as anisometropia of (spherical equivalent) >1.5 D, hyperopia >3.5 D, myopia >3.0 D, astigmatism >1.5 D at 90° or 180°, >1.0 D, any manifest strabismus, any media opacity >1 mm, or ptosis 1 mm or less margin reflex distance 1 along with blunting of vision in that eye. Matched-pair analysis was performed to correlate variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS:

We included 39 children with UNCLDO. The mean axial length was 21.4 ± 1.3 mm for the eyes with UCNLDO and 21.6 ± 1.0 mm for the fellow eye (P = 0.4). Hyperopia >+2 D was present in 17 (44%) eyes with UCNLDO and none of the fellow eyes. None of the participants had strabismus.

CONCLUSION:

Axial length and risk factors of amblyopia such as anisometropia, hyperopia, and strabismus were not associated with UCNLDO. UCNLDO is likely an isolated defect.

Keywords: Amblyopia, anisometropia, childhood blindness, congenital anomalies, congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, refractive error

Introduction

The incidence of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction is 5% among newborns. Up to 90% of these cases resolve spontaneously within the 1st year of life. Unilateral nasolacrimal duct obstruction is less common compared to bilateral cases.[1] Researchers have noted that unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (UCNDLO) is associated with anisometropic amblyopia.[2,3,4,5] The association of these factors to UCNLDO is also affected by age and the number of probing procedures required for treating the obstruction.[6]

Although the mechanism remains controversial, some have postulated that persistent epiphora and discharge causes distortion of the perceived image, which may interfere with emmetropization.[3] Rapid growth of the eye that results in an increase in axial length is the major factor associated with emmetropization. Substantial emmetropization occurs between 3 and 9 months of age, the age associated with peak symptoms of CNLDO. Failure of emmetropization leaves about 2%–8% of children with potentially clinically significant hyperopia after infancy.[4,5]

To the best of our knowledge, this association and the outcomes of intervention for unilateral CNLDO have not been published for Saudi children. Saudi children in the Eastern province have the highest rate of birth defects and metabolic disorders with hereditary etiologies.[7] Consanguinity, an underlying cause of birth defects is reported to be as high as 57.7% in Saudi Arabia.[8] Hence, it would be interesting to review unilateral CNLDO and other ocular parameters linked to developmental defects of one side of the face.

We investigated an association of the axial length of the eye and refractive status to the presence of UCNLDO. We also investigated the association of the amblyopia causing risk factors to outcomes of the management of UCNLDO at two eye institutes in Eastern Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of children with UCNLDO. A retrospective chart review was performed of CNLDO cases registered and managed by probing between January 2009 and April 2015. Exclusion criteria were a history of bilateral nasolacrimal duct obstruction and a history of any intraocular surgery. The Institutional Research Board at King Fahad Hospital of the University and Dhahran Specialist Eye Hospital approved this study. The study was conducted from June 2015 to December 2015. This study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all children in this study. Three ophthalmologists were the field investigators for this study.

We assumed that 22% of children with unilateral CNLDO had risk factors for amblyopia in the affected eye compared to 2% in the fellow eye without CNLDO.[5] To achieve 95% confidence interval (CI) and 80% power for this study with a 1:1 ratio of eyes with and without CNLDO, 41 children were recruited.

The data were collected on patient demographics, including age at presentation, gender, date of birth, date of probing, nationality, and hospital where the patient was managed. A family history of similar problems, history of previous treatment, and presenting symptoms were also noted.

Visual acuity was tested using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study distance vision chart at 6-M. If a child was unable to read at 6 M, the test was repeated at 3 M and acuity notations were adjusted accordingly.

Patients were considered at risk for amblyopia based on the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) criteria.[9] These criteria include anisometropia of (spherical equivalent) >1.5 D, hyperopia >3.5 D, myopia >3.0 D, astigmatism >1.5 D at 90° or 180°, or >1.0 D in oblique axis (<10° eccentric to 90° or 180°), any manifest strabismus, any media opacity in the visual axis >1 mm (causing blurred image or not able to perform refraction), or ptosis 1 mm or less margin reflex distance 1 along with blunting of vision in that eye. The axial length was measured using Echoscan US-800 (NIDEK Co., Ltd., Gamagori, Japan). The difference of 0.9 mm or more in two eyes was considered as significant in our study.[10]

The outcome variables were (1) difference in the axial length between the eye with CNLDO and the unaffected fellow eye; (2) difference in the magnitude of hyperopia in the fellow eye and the affected eye; (3) anisometropia between eyes; and (4) difference in the visual acuity in the fellow eye compared to affected eye. The independent variables were age, gender, a family history of CNLDO, presenting symptoms, and previous probing.

The data were collected on a pretested data collection form and then transferred to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-16; IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) spreadsheet for statistical analysis. If the distribution curve was normal for quantitative variables, the mean and standard deviations were calculated. For variables that were not normally distributed, the median and 25% quartiles were calculated. For qualitative variables, the frequencies and percentage proportions were calculated. Matched-pair analysis was used to compare the outcomes in eyes with CNLDO and the fellow eye. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

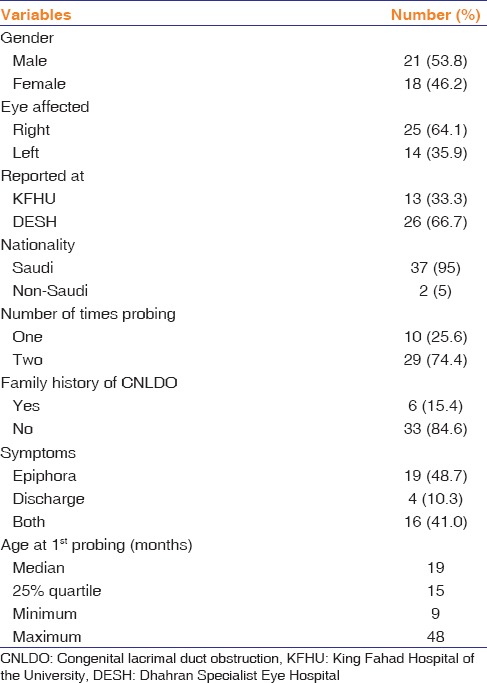

The study sample comprised 39 patients with UCNLDO. The epidemiologic profile, history, and symptoms at the first visit are presented in Table 1. The median age at the last follow-up was 20 months (25% quartile, 16 months; range, 9–102 months).

Table 1.

Demographics and ocular characteristics of patients with unilateral congenital lacrimal duct obstruction

Axial length could be measured in 29 patients only. The mean age was 24 ± 10.2 months (range, 11–102 months). The mean axial length was 21.4 ± 1.4 mm for the eyes with CNLDO and 21.6 ± 1.0 mm for the unaffected fellow eyes (P = 0.4). The axial length of the unaffected fellow eyes was 0.17 mm longer than the CNLDO eyes. This difference was not statistically significant (95% CI, −0.2–0.5; P = 0.4).

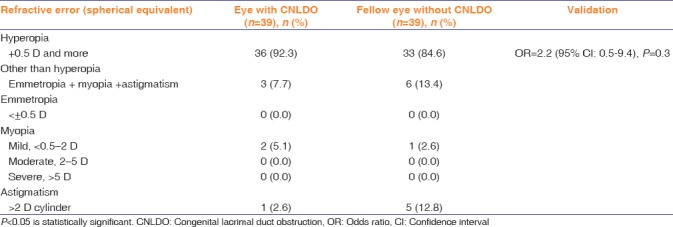

Three (7.7%) participants had a spherical equivalent difference <1.5 D between eyes. However, none of the participant had anisometropia of >1.5 D spherical equivalent difference between eyes. The distribution of refractive error in each eye for the study sample is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Refractive status of eyes with and without congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

The proportion of different types of refractive errors in eyes with CNLDO was not significantly (P > 0.05) different from those in eyes without CNLDO.

In 17 (44%) eyes with UCNLDO, hyperopia was >+2 D. None of the unaffected fellow eyes had hyperopia >2 D. There were no cases of strabismus.

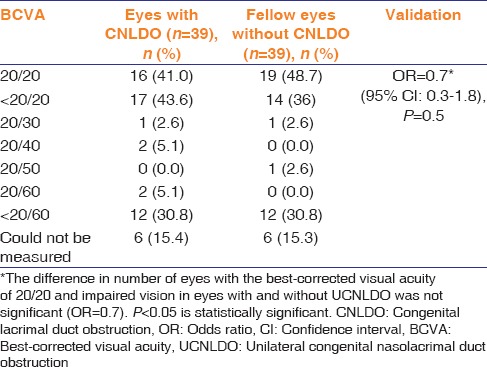

The best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in both eyes is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Best-corrected visual acuity in eyes with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and the fellow unaffected eye

The proportion of eyes with 20/20 BCVA was similar in both groups (P = 0.5).

The correlation of axial length of eyeball to the presence of CNLDO was not statistically significant (P = 1.0). The mean axial length of two eyes with myopic refractive error and UCNLDO was 23.2 ± 0.03 mm. The mean axial length of 37 eyes with UCNLDO without myopia was 21.3 ± 1.6 mm. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Discussion

In the current study, we evaluated risk factors for amblyopia in patients with UCNLDO with persistent symptoms that required a probing procedure. There were no differences in eyes with CNLDO and the unaffected fellow eyes.

CNLDO is one of the most common ophthalmic conditions, occurring in up to 20% of all normal infants.[8] The current guidelines considered probing as a first-line interventional therapy for children with persistent obstruction beyond 1 year of age; however, the optimal timing remains controversial, especially after recent reports that link CNLDO with risk factors for amblyopia.[3,11]

This is perhaps the first study reporting a lack of association between CNLDO and amblyogenic risk factors in children.

In our study, we found that the prevalence of amblyopia risk factors based on the AAPOS criteria was 25.6%. Matta and Silbert[5] reported that 22% of 402 children with CNLDO had risk factors for amblyopia (using AAPOS criteria) and concluded that children who present with CNLDO seem to be more likely to have risk factors for amblyopia. However, a meta-analysis performed in 2013 estimated the prevalence of risk factors for amblyopia (using AAPOS criteria) among normal children to be around 21% ±2%.[12] Perhaps these factors are not developmentally linked. Studies suggesting the causal association of unilateral CNLDO to amblyopia should be critically reviewed. Ellis et al.[2] had suggested that CNLDO does not interfere with visual development in a child. Our study seems to confirm this observation.

A proposed association between dacryostenosis and hyperopic anisometropia was attributed to anatomical orbital factors such as a smaller orbit or tight nasolacrimal passage in conjunction with a short hyperopic eye.[13] However, during embryologic development, fusion of the frontonasal process and lateral nasal fold occurs at different stages of intrauterine life compared to mesodermal tissues around the neuroectodermal tissue developing into the eyeball.[14] Hence, congenital anomalies of the lacrimal drainage system and developmental defects of the globe related to the risk factors for amblyopia are less likely to be due to common factors.

In the current study, we did not find any significant difference of axial length in eye with CNLDO and fellow eye without CNLDO. In eyes with longer axial length in congenital myopia, posterior staphyloma is more common than an overall increase in the size of the globe.[15] Notably, in the current study, myopic eyes with UCNLDO had significantly greater axial length compared to eyes with refractive error other than myopia and unilateral CNLDO. Only low myopia (<2 D) was present in both eyes in the current study. Posterior staphyloma is more likely in high myopes.[16] In the current study, the two myopic eyes with unilateral CNLDO had significantly longer axial lengths compared to other eyes. This observation may suggest a risk of posterior staphyloma in these myopic eyes later in life. Therefore, these patients should be regularly monitored. As there were only two eyes with myopia and unilateral CNLDO in our study sample, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

After calculating spherical equivalent of refraction in each eye, we noted that none of the patients had anisometropia. Two of patients in the current study had hyperopic anisometropia (<1.5 D) with more hyperopia in the eye without CNLDO. The axial length, however, was longer in the eyes with CNLDO compared with unaffected fellow eyes. Some authors speculate that the effect of persistent epiphora on refractive status is similar to the effect of postnatal corneal opacification that induces deprivation myopia by inducing elongation of the globe.[17,18] However, in our study, the difference in the axial length between eyes with CNLDO and the fellow eyes was not significant. This difference was ≤0.3 mm in 86% of children, which is the accepted difference between eyes during axial length measurement.[19]

Kipp et al.[3] evaluated 887 cases of UCNLDO and reported a 7.6% prevalence of anisometropia. Eshraghi et al.[6] noted a significant association with hyperopia and UCNLDO. Bagheri et al.[4] defined anisometropia as more than a 0.5 D difference between eyes and reported that 25% of children with UCNLDO were anisometropic. We used a more stringent definition of anisometropia based on the AAPOS criteria.[9] These different definitions of anisometropia likely explain the variation between our study and study by Kipp et al.[3] There was no significant association between anisometropia and UCNLDO in Saudi children in the current study. Schnall[15] noted that anisometropia was associated with UCNLDO.

Strabismus is a risk factor for amblyopia, and the presence of amblyopia could lead to strabismus.[20] Matta and Silbert[5] reported that 1.6% of children with NLDO required strabismus surgery. The hospital-based prevalence in the same region of Saudi Arabia was as high as 38% among children <15 years old.[21] We evaluated a much younger study sample with a mean age of 7.6 ± 3.6 years. This observation suggests that strabismus may develop later in childhood.

It is recommended that intervention for CNLDO should be performed after 1 year of age.[22] Further delay in intervention, especially in the presence of amblyogenic risk factors, could be detrimental to the child.[5,11] In the current study, one child underwent surgical intervention at 9 months and the remaining children underwent intervention after 12 months of age.

In our study, amblyopia was found in 2 (5%) patients, occurring in the eye with CNLDO. Simon et al.[23] reported five cases of CNLDO with amblyopia in the same eye, all with hyperopic anisometropia in the affected eye. However, in our study, both patients with amblyopia did not have any amblyopic risk factors, but both had persistent tearing and blurry vision for a prolonged period. One patient due to a late procedure (at 2 years) and the other patient underwent probing three times before resolution of the symptoms of CNLDO.

As this is a retrospective study, there are some inherent limitations. It is difficult to establish whether CNLDO was present first, or risk factors for amblyopia were present first and hence a causal relationship of these two variables cannot be established.

In conclusion, UCNLDO is likely an isolated defect and there seems to be no relationship with developmental defects of the globe or the amblyopia risk factors. However, patients with delayed or failed procedures to treat unilateral CNLDO who have persistent blurry vision might be at risk for amblyopia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Department of Ophthalmology staff and the Medical Records Department at King Fahad Hospital of the University and Dhahran Eye Specialist Hospital for their assistance to the investigators.

References

- 1.Lee KA. Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction, Congenital in EyeWiKi. American Academy of Ophthalmology. [Last accessed on 2016 Apr 06]. Available from: http://www.eyewiki.aao.org/Nasolacrimal_Duct_Obstruction_Congenital .

- 2.Ellis JD, MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Can congenital nasolacrimal-duct obstruction interfere with visual development? A cohort case control study. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;35:81–5. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19980301-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kipp MA, Kipp MA, Jr, Struthers W. Anisometropia and amblyopia in nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2013;17:235–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagheri A, Safapoor S, Yazdani S, Yaseri M. Refractive state in children with unilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2012;7:310–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matta NS, Silbert DI. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2011;15:350–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eshraghi B, Akbari MR, Fard MA, Shahsanaei A, Assari R, Mirmohammadsadeghi A, et al. The prevalence of amblyogenic factors in children with persistent congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:1847–52. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2643-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Bu Ali WH, Balaha MH, Al Moghannum MS, Hashim I. Risk factors and birth prevalence of birth defects and inborn errors of metabolism in Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;8:14. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Hazmi MA. Haemoglobinopathies thalassemias and enzymopathies in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 1992;13:488–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Refractive Error and Refractive Surgery PPP – 2013. [Last accessed on 2016 May 18]. Available from: http://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/refractive-errors-surgery-ppp-2013 .

- 10.Oliveira C, Harizman N, Girkin CA, Xie A, Tello C, Liebmann JM, et al. Axial length and optic disc size in normal eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:37–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.102061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi Y, Kang H, Kakizaki H. Axial globe length in congenital ptosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015;52:177–82. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20150326-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold RW. Amblyopia risk factor prevalence. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2013;50:213–7. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20130326-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyi Son MK, Hodge DO, Mohney BG. Timing of congenital dacryostenosis resolution and the development of anisometropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1112–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barishak YR. Embryology of the eye and its adnexa. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. Barishak, YR (Ramat Gan) 2001 doi: 10.1159/isbn.978-3-318-00662-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaoka N, Ohno-Matsui K, Saka N, Tokoro T, Mochizuki M. Clinical characteristics of patients with congenital high myopia. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s10384-010-0896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang L, Pan CW, Ohno-Matsui K, Lin X, Cheung GC, Gazzard G, et al. Myopia-related fundus changes in Singapore adults with high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:991–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mataftsi A, Vlavianos A, Tsaousis KT, Tzamalis A, Dimitrakos SA. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2012;16:213–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raviola E, Wiesel TN. An animal model of myopia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1609–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnall BM. Pediatric nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24:421–4. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283642e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orssaud C. Amblyopia. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2014;37:486–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tamimi ER, Shakeel A, Yassin SA, Ali SI, Khan UA. A clinic-based study of refractive errors, strabismus, and amblyopia in pediatric age-group. J Family Community Med. 2015;22:158–62. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.163031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dotan G, Nelson LB. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: Common management policies among pediatric ophthalmologists. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015;52:14–9. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20141028-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon JW, Ngo Y, Ahn E, Khachikian S. Anisometropic amblyopia and nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46:182–3. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090505-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]