Abstract

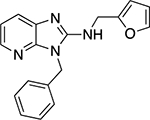

The transient receptor potential cation channel 5 (TRPC5) has been previously shown to affect podocyte survival in the kidney. As such, inhibitors of TRPC5 are interesting candidates for the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Herein, we report the synthesis and biological characterization of a series of N-heterocyclic-1-benzyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-amines as selective TRPC5 inhibitors. Work reported here evaluates the benzimidazole scaffold and substituents resulting in the discovery of AC1903, a TRPC5 inhibitor that is active in multiple animal models of CKD.

Keywords: transient receptor potential cation channel 5, TRPC5, inhibitor, chronic kidney disease, AC1903

Graphical Abstract

To create your abstract, type over the instructions in the template box below. Fonts or abstract dimensions should not be changed or altered.

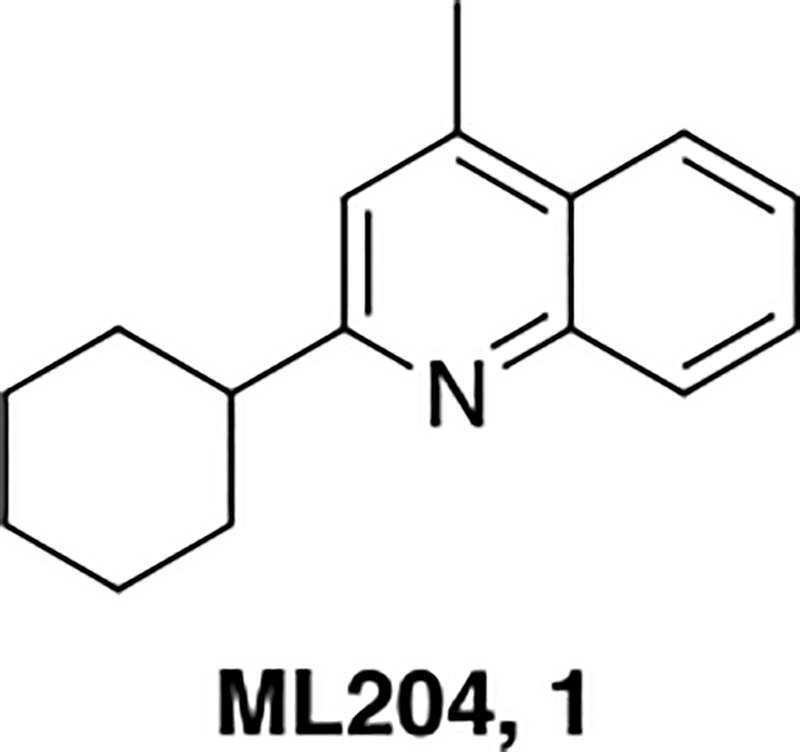

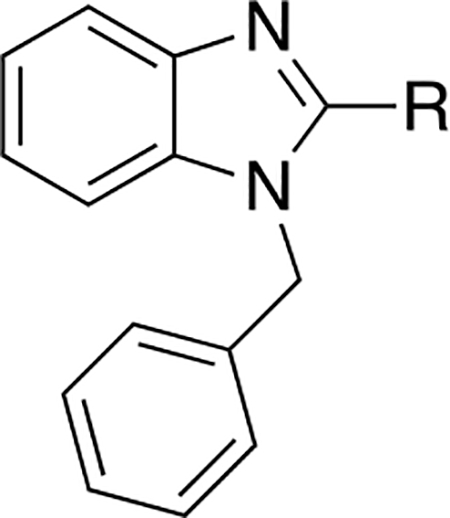

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a type of kidney disease associated with gradual loss of kidney function which affects >300 million people worldwide.1,2 Although many factors contribute to CKD, the leading diagnosis of CKD is focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) – characterized by proteinuria and scarring of the glomerulus.3 Although the patient burden of CKD is large, there has been a dearth of new treatment options developed over the past several decades. Recently, the TRPC5 ion channel has emerged as a potential new target for the development of novel treatments for CKD.4 The mammalian superfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channels is comprised of six subfamilies of receptors: TRPV (vanilloid), TRPC (canonical), TRPM (melastatin), TRPA (ankyrin), TRPP (polycystin) and TRPML (mucolipin). The TRPC subfamily is further subdivided into seven members (TRPC1–7) based on sequence similarities: TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3/6/7, and TRPC4/5.5 Due to their localization, the TRPC4/5 subfamily has been implicated in a variety of disease areas, including: drug dependence, anxiety and kidney filtration.6 In fact, an initial TRPC4/5 inhibitor (ML204,1) was shown to protect the kidney filter in an in vivo animal model.7 Although ML204 (Figure 1) was an important initial tool compound, the selectivity profile around this molecule was less than ideal, (inhibitor of both TRPC4 and 5) and thus, our laboratories set out to identify a selective TRPC5 inhibitor. As part of this endeavor, we have recently published on the novel TRPC5 inhibitor, AC1903, and herein, we report the synthesis and structure activity-relationship (SAR) studies around the discovery of AC1903.8

Figure 1.

The structure of the quinoline TRPC5 inhibitor, ML204, 1.

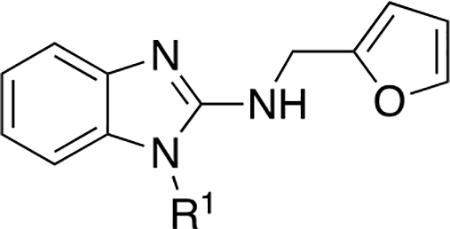

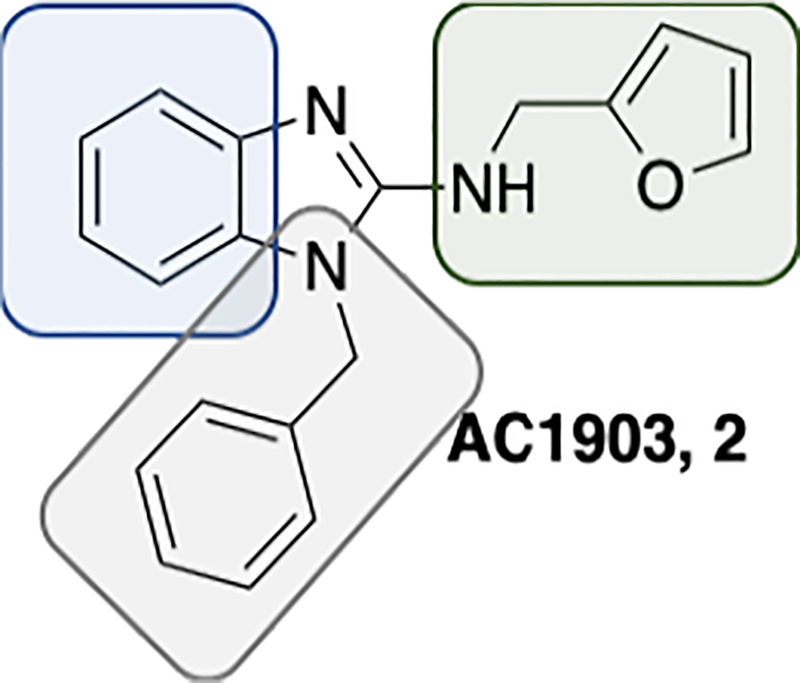

From a high-throughput screen performed at the Johns Hopkins Ion Channel Center (JHICC) utilizing the >300,000 NIH Molecular Library Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) compound collection, we identified a number of benzimidazole containing compounds as TRPC4/5 inhibitors for transition into a lead optimization campaign.9 These molecules afforded an excellent starting point for a medicinal chemistry effort as they were low MW (<300), offered multiple points of diversification, and satisfied many parameters for tool compound development (e.g., cLogP <3). As exemplified in the optimized compound 2, the areas for chemical modification were the left-hand phenyl of the benzimidazole, the 2-position of the benzimidazole, and the southern benzyl moiety.

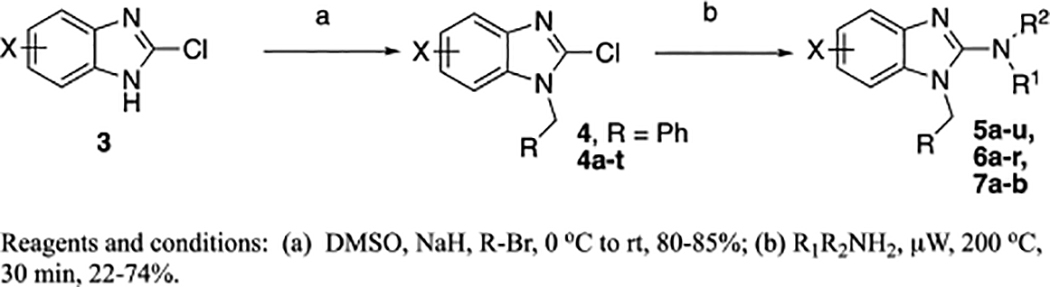

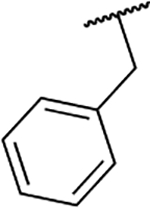

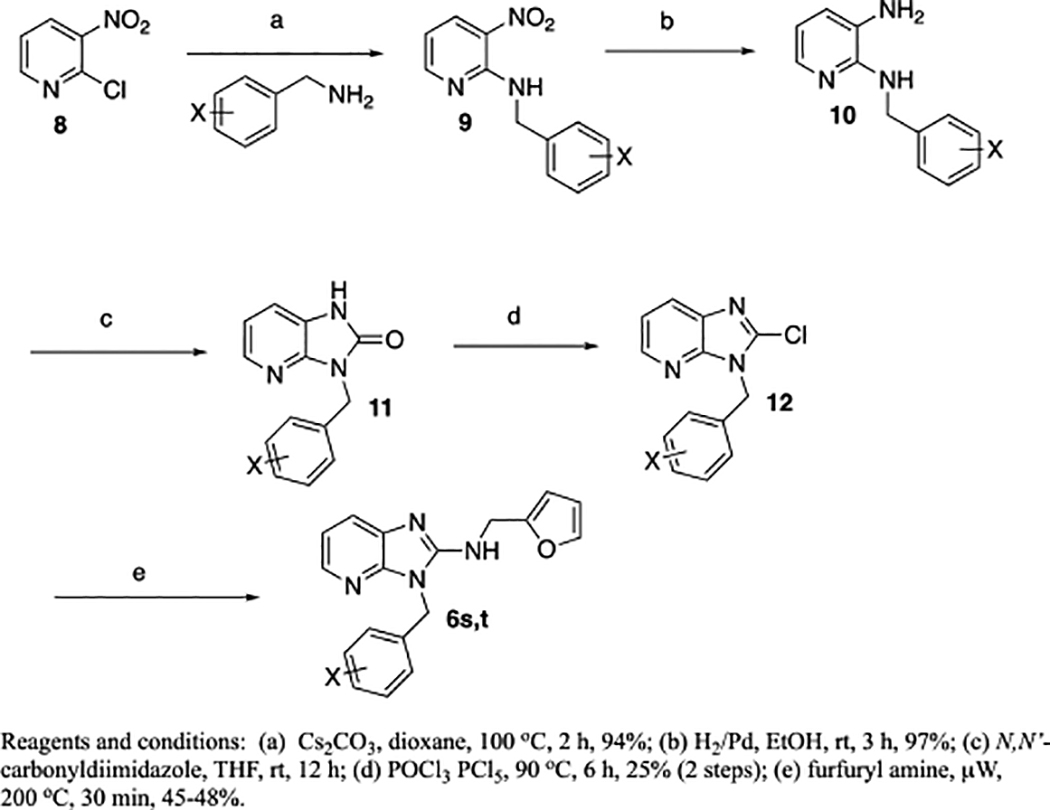

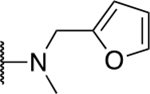

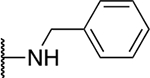

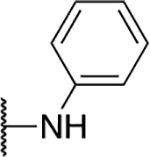

The synthesis of the desired benzimidazole compounds is shown in Scheme 1. The initial library centered around keeping the southern benzyl groups constant while modifying the right-hand 2-benzimidazole moiety. This was done by reacting the 2-chlorobenzimidazole (or substituted benzimidazole), 3, with benzyl bromide under basic conditions (NaH, DMSO, 0 °C to rt). Next, the resulting compounds, 4 (4, R = Ph, 4a-t, as detailed in Table 2), were reacted with the appropriate amine (neat) under microwave heating (μW, 200 °C, 30 min) to yield the desired compounds 2, 5a-u and 7a-b. The next set of compounds, 6a-t, were synthesized in a similar manner, except the starting material, 3, was modified with the appropriate alkyl or benzyl bromide to give 4, followed by reaction with furfuryl amine under microwave conditions to yield 6a-r.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the target benzimidazoles.

Table 2.

Evaluation of southern portion.

| Cmpd | R1 | % Inhibition Syncropatch (@ 3 μM, ± SEM)a |

|---|---|---|

| 2 |  |

100 |

| 6a |  |

81.2 ± 6.4 |

| 6b |  |

34.4 ± 4.0 |

| 6c |  |

65.2 ± 8.1 |

| 6d |  |

117 ± 5.5 |

| 6e |  |

61.6 ± 4.5 |

| 6f |  |

91.1 ± 4.7 |

| 6g |  |

61.9 ± 4.6 |

| 6h |  |

54.4 ± 4.5 |

| 6i |  |

2.6 ± 10.4 |

| 6j |  |

50.5 ± 5.8 |

| 6k |  |

87.0 ± 6.4 |

| 6l |  |

70.9 ± 6.6 |

| 6m |  |

94.6 ± 3.4 |

| 6n |  |

70.2 ± 3.9 |

| 6o |  |

167 ± 3.1 |

| 6p |  |

88.4 ± 4.5 |

| 6q |  |

128 ± 4.7 |

| 6r |  |

23.6 ± 3.5 |

| 6s |  |

31.2 ± 5.3 |

| 6t |  |

21.7 ± 6.4 |

| 7a |  |

28.2 ± 4.5 |

| 7b |  |

123 ± 3.7 |

The % inhibition values were recorded in cells (n > 10) using the Syncropatch (Nanion). Experiments were recorded (minimum) on one session over two different assay plates. AC1903 and DMSO were added as control compounds on every assay plate.

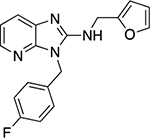

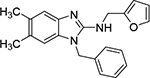

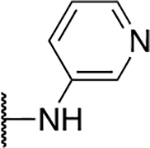

In addition to the benzimidazoles, we also evaluated 3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridines (6s,t) and the synthesis of these analogs are shown in Scheme 2. The 2-chloro-3-nitropyridine, 8 starting material was reacted with an appropriate benzyl amine (Cs2CO3, 100 °C, 2 h) to yield 9.10 The resulting nitropyridine, 9, was reduced (H2, Pd/C) to yield the dianiline, 10, which was converted to the imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine-2-one, 11, with N,N’-carbonyldiimidazole. Compound 11 was converted to the 2-chloro compound (POCl3, PCl5, 90 °C) which was then reacted with furfurylamine under microwave heating (μW, 200 °C, 30 min) yielding the final targets, 6s,t.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridines, 6s,t.

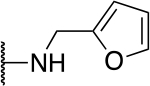

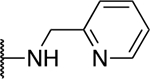

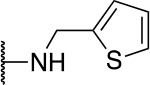

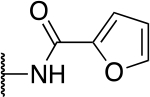

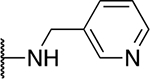

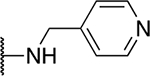

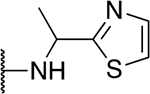

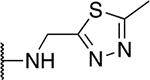

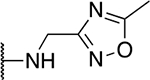

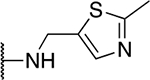

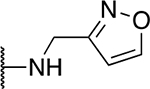

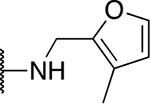

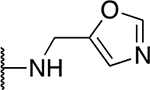

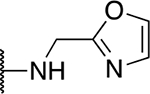

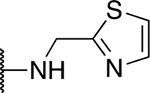

The SAR of the 2-benzimidazole position is outlined in Table 1. The furfuryl amine substituent, 2, was used as the standard control and the % inhibition at 3 μM was normalized to 100%. We utilized a first triage of % inhibition of the TRPC5 channel using the Syncropatch instrument in order to have a higher throughput capacity for SAR, which is then followed up with IC50 determinations of active compounds. Knowing the furan moiety is prone to oxidation and thus metabolic instability, we set out to investigate furan replacements. Replacing the furan with 2-pyridyl compound (5a, −1.8% inhibition) was not a productive change, neither were any of the other pyridine regioisomers (5h, 5i). Moving from the furan to the 2-thiophene led to a compound that was active (5b, 150% inhibition). Replacing the 2-thiophene with a phenyl bioisostere led to a reduction in activity (5e, 33% inhibition). In addition, replacing the methylene linker with a carbonyl (amide) or capping the free NH with a methyl also led to less active compounds (5c, 5d). In addition, removing the methylene linker (5f, 5g) or removing the amino substituent (Me, 5j) were not productive. A variety of 5-memebered aryl heterocyclic replacements were investigated as furan alternative (5k-u). Unfortunately, all of the thiazole, thiadiazole and oxazole isomers led to reduced potency compounds. The only two changes that produced active compounds were the 3-methyl-2-furyl derivative (5q, 82% inhibition) and the methine branched furan (5u, 91% inhibition).

Table 1.

SAR evaluation of the 2-benzimidazole moiety.

| Cmpd | R | % Inhibition Syncropatch (@ 3 μM,± SEM)a |

|---|---|---|

| 2 |  |

100 |

| 5a |  |

−1.8 ± 7.9 |

| 5b |  |

150 ± 4.0 |

| 5c |  |

38.5 ± 3.8 |

| 5d |  |

41.7 ± 4.9 |

| 5e |  |

32.8 ± 5.4 |

| 5f |  |

18.9 ± 6.1 |

| 5g |  |

19.9 ± 2.6 |

| 5h |  |

12.0 ± 4.4 |

| 5i |  |

17.4 ± 3.6 |

| 5j | −CH3 | 19.0 ± 3.7 |

| 5k |  |

45.0 ± 4.4 |

| 5l |  |

18.0 ± 7.0 |

| 5m |  |

30.0 ± 4.7 |

| 5n |  |

19.8 ± 4.6 |

| 5o |  |

35.7 ± 7.4 |

| 5p |  |

47.0 ± 3.4 |

| 5q |  |

82.3 ± 4.9 |

| 5r |  |

33.3 ± 4.7 |

| 5s |  |

19.1 ± 3.5 |

| 5t |  |

42.5 ± 3.5 |

| 5u |  |

91.4 ± 6.6 |

The % inhibition values were recorded in cells (n > 10) using the Syncropatch (Nanion). Experiments were recorded (minimum) on one session over two different assay plates. AC1903 and DMSO were added as control compounds on every assay plate.

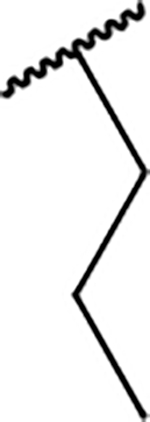

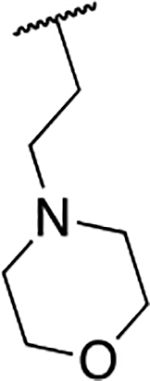

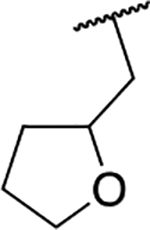

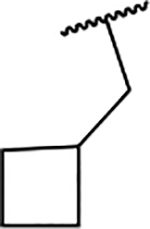

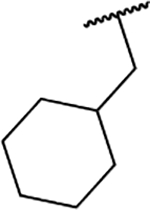

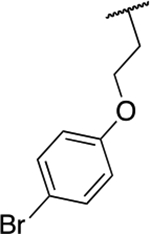

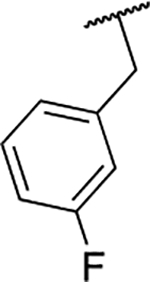

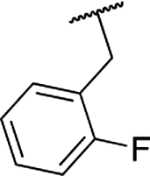

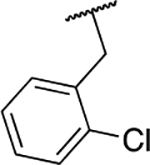

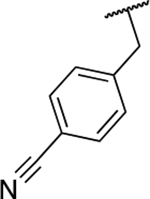

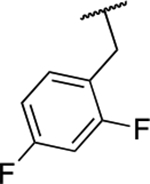

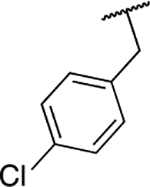

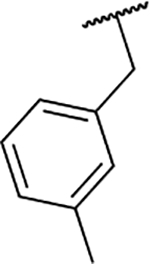

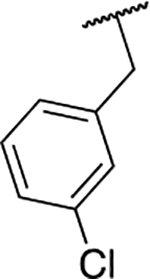

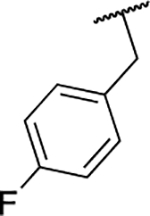

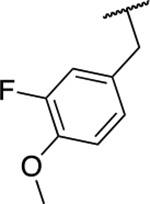

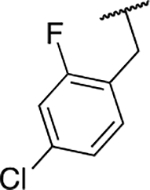

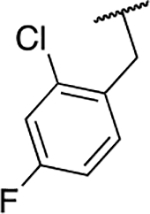

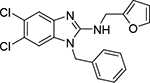

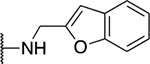

Next, we evaluated the southern benzimidazole substituents by keeping the furan-2-ylmethyl amine group constant (Table 2). Moving from the benzyl group to a propyl led to a slight decrease in activity (6a) and further modification with an ethyl morpholine provided an inactive compound (6b, 34% inhibition). Additional moieties that contained basic amines (piperdine) were also not tolerated (data not shown). Further modification of the alkyl substituents with cyclic moieties yielded moderately active compounds, with the exception of the cyclobutene derivative (6d, 117% inhibition). Adding a phenyl ring to the 3-atom spacer brought back the activity (6f, 91% inhibition). We also evaluated a number of phenyl substituted analogs (6g-r). Most of these analogs were of moderate activity (~50–70% inhibition), with a few highlighted exceptions. The 2-chlorophenyl (6i, 2.6%) and the 2-chloro-4-fluorophenyl (6r, 24% inhibition) were much less active than other groups – even less active than the 2-fluoro substituted analogs (e.g., 6h, 6q). The best compounds from this evaluation were 4-fluorophenyl (6o, 167% inhibition) and the 4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl (6q, 128% inhibition). Interestingly, changing the core scaffold from the benzimidazole to the azabenzimidazole (6s and 6t) led to compounds with reduced activity. Lastly, addition of substituents on the phenyl ring of the benzimidazole (positions 5- and 6-) showed a noticeable trend. The 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole (7a, 28% inhibition) was significantly less active than the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole (7b, 123% inhibition) suggesting an electronic effect of the substituent groups.

Having identified a number of compounds with activity as TRPC5 inhibitors at 3 μM, we next followed up these compounds with IC50 determinations. Compound 2 (AC1903) had an IC50 = 4.06 μM, as determined using the Syncropatch. This value is comparable to the manual patch clamp historical value for this compound.8 Most of the compounds tested had comparable IC50 values to 2. However, there are a few notable exceptions. Compounds 6a (IC50 = 15.5 μM), 6p (IC50 = 11.6 μM), 6q (IC50 = 18.1 μM) and 7b (IC50 = 12.3 μM) were less potent than 2. Thus, the % inhibition values were mostly equivalent to 2 (with a couple exceptions) and this translated to similar IC50 values. Some of the minor assay discrepancies may be due to the fact that the % inhibition assay is run as one concentration in one well versus multiple concentrations in multiple wells for the IC50 determinations. None of the synthesized analogs were significantly improved over 2.

Again, to progress 2 into in vivo studies we performed an in vivo pharmacokinetic study (IP dosing, 25 mg/kg, 0 – 24 h). The results of this study are shown in Table 4. Compound 2 was shown to have PK values similar to ML204 and based on these values we progressed this compound into a variety of animal studies of kidney disease (previously reported).8 In addition, 2 was shown to be selective for TRPC5 over TRPC4 and TRPC6.8

Table 4.

In vivo PK for 2.

| IP, 25 mg/kg, vehicle: 5% DMSO, 10% Tween80, 85% PBS | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 687 |

| Tmax (hr) | 0.11 |

| AUC (hr-ng/mL) | 1130 |

We herein described the synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of 2-aminobenzimidazole compounds as TRPC5 inhibitors. The SAR revelaed that modifications or replacement of the furan moiety were not tolerated. In addition, the southern moiety SAR revealed that there is tolerance of many phenyl analogs as well as non-phenyl ring systems (cyclobutane). Further evaluation using the Syncropatch for IC50 determination revealed that 2 (AC1903) was the best compounds that was identified. Thus, we have revealed the synthesis and biological characterization of the novel TRPC5 inhibitor 2 (AC1903) which we’ve previously shown to be active in a number of animal models of kidney disease. Further modifications of new TRPC5 inhibitors will be reported in due course.

Figure 2.

Structure and modification points of AC1903, 2.

Table 3.

IC50 determinations of select compounds.

| Cmpd | % inhibition at 3 μM | TRPC5 IC50 (μM ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 100 | 4.06 ± 0.91 |

| 5b | 150 | 6.26 ± 1.59 |

| 5q | 82.3 | 6.93 ± 1.53 |

| 5u | 91.4 | 4.44 ± 1.12 |

| 6a | 81.2 | 15.5 ± 5.4 |

| 6k | 87.0 | 8.42 ± 3.07 |

| 6m | 94.6 | 4.80 ± 1.14 |

| 6o | 167 | 1.82 ± 0.32 |

| 6p | 88.4 | 11.6 ± 3.9 |

| 6q | 128 | 18.1 ± 9.7 |

| 7b | 123 | 12.3 ± 7.0 |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Anna L. Blobaum (Vanderbilt University) for the in vivo PK study of AC1903. The study was supported by a grant from the NIH (NIDDK: R01DK103658) to C. R. H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data (synthetic procedures) to this article can be found online at.

References and notes

- 1.Webster AC; Nagler EV; Morton RL; Masson P Lancet 2017, 389, 1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romagnani P; Remuzzi G; Glasscock R; Levin A; Jager KJ; Tonelli M; Massy Z; Wanner C; Anders H-J Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Agati VD; Kaskel FJ; Falk RJ N. Engl. J. Med 2011, 365, 2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bezzerides VJ; Ramsey IS; Kotecha S; Greka A; Clapham DE Nat. Cell. Biol 2004, 6, 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez G; Wedel BJ; Aziz O; Trebak M; Putney JW Jr. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1742, 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wescott SA; Rauthan M; Xu XZ S. Life Sci 2013, 92, 410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaldecker T; Kim S; Tarabanis C; Tian D; Hakroush S; Castonguay P; Ahn W; Wallentin H; Heid H; Hopkins CR; Lindsley CW; Riccio A; Buvall L; Weins A; Greka AJ Clin. Invest 2013, 123, 5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y; Castonguay P; Sidhom E-H; Clark AR; Dvela-Levitt M; Kim S; Sieber J; Wieder N; Jung JY; Andreeva S; Reichardt J; Dubois F; Hoffman SC; Basgen JM; Montesinos MS; Weins A; Johnson AC; Lander ES; Garrett MR; Hopkins CR; Greka A Science 2017, 358, 1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M; Shi J; Zhu Y; Kustov M; Tian JB; Stevens A; Wu M; Xu J; Long S; Yang P; Zholos AV; Salovich JM; Weaver CD; Hopkins CR; Lindsley CW; McManus O; Li M; Zhu MX J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh S; Kim S; Kong S; Yang G; Lee N; Han D; Goo J; Siqueira-Neto JL; Freitas-Junior LH; Song R Eur. J. Med. Chem 2014, 84, 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]