Abstract

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), pain, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) commonly co-occur in Veteran populations, particularly among Veterans returning from the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Extant research indicates that both TBI and PTSD can negatively impact pain broadly; however, less is known about how these variables impact one another. The current study examines the impact of self-reported post-concussive symptoms on both pain severity and pain interference among Veterans with PTSD who screened positive for a possible TBI, and subsequently, evaluates the potential mediating role of PTSD in these relationships.

Materials and Methods

Participants were 126 combat Veterans that served in Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, or Operation New Dawn who were being evaluated for participation in a multisite treatment outcomes study. As part of an initial evaluation for inclusion in the study, participants completed several self-report measures and interviews, including the Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen, Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory, Brief Pain Inventory, and the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, which were utilized in these analyses.

Results

For pain severity, greater post-concussive symptoms significantly predicted increased pain severity with a significant indirect effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain severity through PTSD (indirect effect = 0.03; 95% confidence interval = 0.0094–0.0526). Similar results were found for pain interference (indirect effect = 0.03; 95% confidence interval = 0.0075–0.0471).

Conclusions

These findings replicate and extend previous findings regarding the relationship between TBI, pain, and PTSD. Self-reported post-concussive symptoms negatively impact both pain severity and pain interference among Veterans with probable TBI, and PTSD serves as a mediator in these relationships. Clinically, these results highlight the importance of fully assessing for PTSD symptoms in Veterans with a history of TBI presenting with pain. Further, it is possible that providing effective PTSD treatment to reduce PTSD severity may provide some benefit in reducing post-concussive and pain symptoms.

Keywords: PTSD, TBI, pain, OEF/OIF/OND, veterans

INTRODUCTION

Extant research indicates that pain is the most common physical complaint among Veterans who served in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF),1 or Operation New Dawn (OND) and pain symptomology commonly co-occurs with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2,3 The co-occurrence between PTSD and pain in this Veteran population is well documented, with estimates ranging between 10% and 50%.4,5 Not surprisingly, this comorbidity has a greater negative impact on symptoms, quality of life, and overall functioning compared with either disorder alone. For example, individuals diagnosed with PTSD reported more severe pain and poorer quality of life than those who reported only chronic pain with no diagnosis of PTSD.6 In addition, Veterans with chronic pain report higher rates of PTSD than the general population2 and Veterans with both pain and PTSD report increased severity of pain, greater disability related to pain, and greater disruption in normal functioning.2,7,8

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is another common concern among the OEF/OIF/OND population and has been referred to as the “signature injury” of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. One common cause of TBI is blast exposure, which accounts for approximately 65% of all injuries from these conflicts.9 Pain is frequently reported among Veterans with TBI and can also be a consequence of TBI.9 In the OEF/OIF/OND population, almost half of combat troops receiving care for headaches have a history of TBI.10

Characteristics of the current conflicts, such as number of deployments and length of conflicts, may contribute to the high rates of injury and pain. For instance, most service members report multiple deployments and wear and tear on the body is common in these intense deployed environments. This combination of factors places service members at an increased risk for exposure to injuries and situations that could result in the development of pain or TBI. Sherman and colleagues postulated that injury-related events as well as changes to the brain’s cognitive and perceptual functions play a role in the association between TBI and pain, but that it is likely that there are also other factors which impact this relationship.11 One factor which complicates treatment and assessment of comorbid pain and TBI is the presence of psychiatric disorders as altered emotional states can impact both subjective experience of pain and cognitive functioning.12

OEF/OIF/OND Veterans who have experienced a TBI frequently meet criteria for one or more psychiatric disorders, with PTSD being one of the most common psychiatric conditions seen in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans with TBI.13 Similar to findings for comorbid pain and PTSD, Veterans with comorbid PTSD and TBI experience greater symptomology, including re-experiencing symptoms, emotional reactivity, hyperarousal, avoidance, and sleep disturbances, compared with those with PTSD alone.14 Moreover, there is some evidence that individuals with both PTSD and TBI perform more poorly on neuropsychological measures than those with either diagnosis separately.15 Similarly, a recent study found that the co-occurrence of PTSD and TBI had a more detrimental impact on functional outcome than either diagnosis alone.16

Research in recent years has found that pain, PTSD, and TBI frequently co-occur together as a group among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans5,17 This combination has been referred to as the “polytrauma clinical triad.”17,18 While the exact reasons for this co-occurring triad are unknown, Otis and colleagues contend that a variety of factors specific to the OEF/OIF/OND conflicts contribute to the polytrauma triad, including increased length of tours and multiple deployments, increased exposure to physical and psychological stressors, increased exposure to physical trauma (e.g., blasts, explosions), and a greater ability to survive injuries due to advances in gear (e.g., body armor) and medical care.19 They suggest that this combination of factors places individuals at an increased risk for stress-related mental health issues (e.g., PTSD), as well as physical injuries and complaints (e.g., TBI, post-concussive symptoms, pain).

These issues interact with increasing negative effects of each on the other, thus it is critical to better understand the interplay between them. Both TBI and PTSD negatively impact pain,2,6,7,11,12 but less is known about the relationship between TBI, PTSD, and pain. With the co-occurrence of TBI and PTSD, it seems likely that factors involved in the development and maintenance of one may influence the other. Some research examining the impact of TBI and PTSD on pain suggests that Veterans with comorbid TBI and PTSD report higher levels of subjective pain compared to those with only one of these disorders.17 Further, Stojanovic and colleagues17 found a significant association between perceived pain and functional impairment. While existing research has identified that both TBI and PTSD can negatively impact pain broadly, less is known about the impact of post-concussive symptoms following a probable TBI on pain severity and interference (i.e., difficulties with movement or work) above and beyond the effects of PTSD. Additionally, given the negative impact emotional distress can have on both cognitive functioning and perceived pain, it is important to understand the role of PTSD in the relationship between post-concussive symptoms and pain severity and interference. Thus, the aims of the current study were to replicate and extend prior research findings by (1) examining the impact of post-concussive symptoms on both pain severity and pain interference among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans with PTSD and probable TBI, and if a significant relationship exists, to (2) evaluate the potential mediating role of PTSD in this relationship.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were comprised of 126 combat OEF/OIF/OND Veterans, evaluated between 2011 and 2016 as part of a larger multisite randomized control trial funded by the Department of Defense (PROlonGed ExpoSure Sertraline: Randomized Controlled Trial of Sertraline, Prolonged Exposure Therapy and Their Combination of OEF/OIF with PTSD; PROGrESS). Details regarding the larger study are published elsewhere.20 Data for the current study were obtained during the initial baseline evaluation for inclusion into the larger study and represents all participants who applied, including combat controls and those who were ineligible for inclusion in the treatment portion of the study. However, only participants who were positive on the TBI screener21 (The Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen [BTBIS]) were included in the analyses for this study. During the evaluation, participants completed self-report measures and structured diagnostic interviews that assessed for a range of symptoms and conditions including PTSD, self-reported post-concussive symptoms, and pain, which were used in these analyses.

The resulting sample was 97.6% male, primarily Caucasian (73.8%), and was an average age of 35.02 (SD = 10.92). Participants reported an average of 2.79 deployments, served predominately in Iraq (81%), and were primarily from the regular armed services (i.e., Air Force, Army, Marines, Navy; 84.1%). See Table I for full descriptive characteristics of this sample.

TABLE I.

Descriptive Statistics and Sample Characteristics (N = 126)

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.02 (10.92) |

| Gender (male) | 123 (97.6%) |

| Race | |

| White | 93 (73.8%) |

| Black | 22 (17.5%) |

| Other | 11 (8.8%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 17 (13.5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or remarried | 60 (47.6%) |

| Separated or divorced | 30 (23.8%) |

| Never married | 36 (28.6%) |

| Education (years) | 13.84 (1.92) |

| Military history | |

| Regular armed services | 106 (84.1%) |

| National Guard | 18 (14.3%) |

| Reserve | 1 (0.8%) |

| Number of deploymentsa | 2.79 (3.1) |

| Deployed to Iraq | 102 (81%) |

| Deployed to Afghanistan | 56 (44.4%) |

| CAPS | 70.16 (27.34) |

| NSI | 34.16 (17.20) |

| BPI severity | 4 (2.63) |

| BPI interference | 3.56 (2.85) |

Note. All percentages are valid percents, these may not equal 100% due to rounding. CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; NSI = Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory; BPI = Brief Pain Inventory.

aTotal deployments over military career.

Measures

Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form

The Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI) is a self-report measure of pain that evaluates both pain severity (0: no pain through 10: pain as bad as you can imagine) and impairment related to pain (0: does not interfere through 10: interferes completely).22 A separate score for pain severity and impairment from pain was calculated. Data on the psychometric properties of the measure have shown that it has good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and validity.23,24 The participants’ average pain severity (range: 0–40) and overall interference score (range 0–70) were utilized in the current analyses.

The Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen

The Brief Traumatic Brain Injury Screen (BTBIS), which is also known as The 3 Question DVBIC TBI Screening Tool, is a three-item questionnaire used to screen Veterans and Service Members for potential mild traumatic brain injuries that they may have endured during their service.21 The questions assess for the presence of an event that could have caused a TBI and resulted in injury (e.g., blast exposure), the experience of TBI symptoms around the time of the event (e.g., loss of consciousness), and current symptoms that may be related (e.g., headache, memory problems). While an official TBI diagnosis cannot be made from this screener, if the person endorses the first two aspects, it is considered a positive TBI screen. In the current study, participants were included in the sample if they screened positive on this measure and deemed as having a “probable TBI.”

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview for PTSD, which assesses the frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms.25 Scores range from 0 to 136, with greater scores indicating greater frequency and/or intensity of symptoms. It has been shown to be a psychometrically strong instrument with test–retest reliabilities between 0.90 and 0.98 and internal consistency of 0.94 for total score.26 Based on the timeframe of this study, the original CAPS based on criteria from DSM-IV-TR were used. The current study used the total score for the past month in the analyses.

Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory

The Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory (NSI) is a self-report questionnaire that is commonly used within the VA to assess for neurobehavioral symptoms that are purported to represent post-concussive, mild TBI symptoms.27 The measure consists of 22 items that assesses symptoms from the past 2 weeks on a 0 (none) to 4 (very severe) scale, where higher scores indicate greater severity of symptoms (range: 0–88). Previous findings have demonstrated that the measure has good internal consistency (0.95 for total score) and is a valid measure, although data also demonstrated that results are strongly influenced by aspects of psychological distress.28

Analytic Plan

Bivariate correlations were computed to assess the relationships between the primary dependent variables (i.e., BPI pain severity, BPI interference from pain), independent variable (NSI), and proposed mediator (CAPS total score). The mediation analyses for this study were conducted using PROCESS in SPSS in order to obtain the total, direct, and indirect effects of post-concussive symptoms on pain severity and interference through PTSD severity.29–31 Separate mediation analyses were conducted for each of the dependent variables. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions using 10,000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples were conducted to estimate all models and effects.

RESULTS

Descriptive Data and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistics and sample characteristics are presented in Table I. The associations among the independent variable, dependent variable, and the proposed mediator are presented in Table II. All study variables were significantly positively associated with one another.

TABLE II.

Intercorrelations Among Proposed Mediator, Independent, and Dependent Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CAPS Total | – | 0.62** | 0.48** | 0.49** |

| 2. NSI Total | – | – | 0.47** | 0.54** |

| 3. BPI Severity | – | – | – | 0.79** |

| 4. BPI Interference | – | – | – | – |

Note. A double asterisk indicates correlation is significant at 0.01 level.

Mediation Analyses

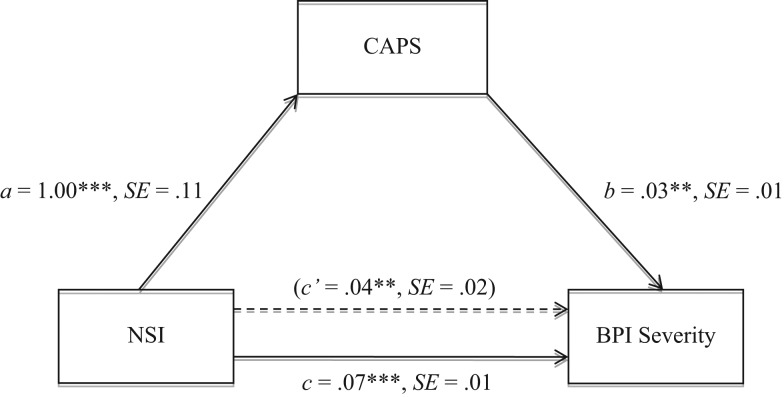

The following models were estimated using PROCESS in SPSS. In terms of pain severity, Model 1 represents the total effect of self-reported post-concussive symptoms (NSI total score) on pain severity (BPI pain severity score). Results indicated that increased post-concussive symptoms significantly predicted greater perceived pain severity (Table III, Model 1 and Fig. 1 path c). Model 2 represents the effect of post-concussive symptoms on PTSD symptom severity (CAPS total score) and results indicated that having greater post-concussive symptoms significantly predicted higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Table III, Model 2 and Fig. 1 path a). The direct effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain severity after accounting for the influence of PTSD symptom severity is represented in Model 3. PTSD symptoms were positively associated with pain severity (Table III, Model 3 and Fig. 1 path b), and the direct effect of post-concussive symptoms was positively associated with pain severity after accounting for the effect of PTSD symptoms (Table III, Model 3 and Fig. 1 path c’). PROCESS directly calculates the indirect effect (by multiplying the path a coefficient by the path b coefficient obtained from the OLS regression analyses) as well as the corresponding confidence interval. For the current analyses, the indirect effect was calculated as ab = 1.00 × 0.03 = 0.03 and the resulting confidence interval (95% CI = 0.0094–0.0526) did not include zero, suggesting a significant indirect effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain severity through PTSD symptom severity. That is, PTSD symptom severity serves as a partial mediator of the association between perceived post-concussive symptoms and pain severity.

TABLE III.

OLS Regression Model Coefficients for BPI Severity

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | BPI Severity | CAPS | BPI Severity |

| Constant | 1.56** | 35.94*** | 0.48 |

| NSI | 0.07*** | 1.00*** | 0.04** |

| CAPS | 0.03** | ||

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.28 |

Note. All Models contain unstandardized OLS regression coefficients with OLS R2.

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

FIGURE 1.

Path coefficients for simple mediation analysis on BPI pain severity. Dotted line denotes the effect of self-reported post-concussive symptoms on pain severity when PTSD symptom severity is included as a mediator. a, b, c, and c’ are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

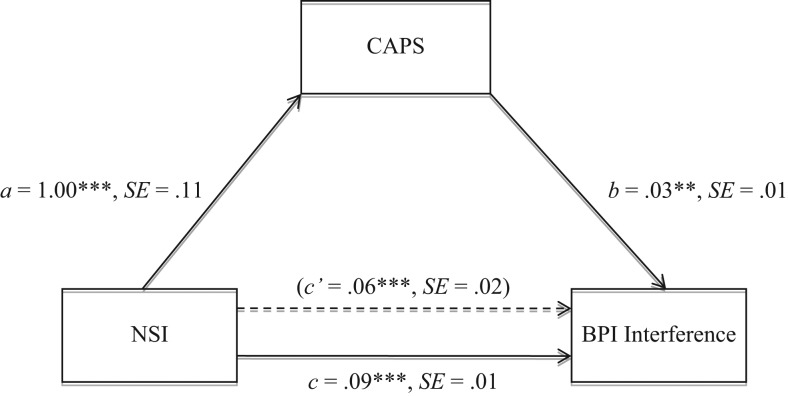

With regard to reported interference from pain, Model 4 represents the total effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain interference (BPI pain interference score). Results indicated that increased post-concussive symptoms significantly predicted greater perceived interference from pain (Table IV, Model 4 and Fig. 2 path c). Model 5 represents the effect of post-concussive symptoms on PTSD symptom severity and results indicated that having greater post-concussive symptoms significantly predicted higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Table IV, Model 5 and Fig. 2 path a). The direct effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain interference after accounting for the influence of PTSD symptom severity is represented in Model 6. PTSD symptoms were positively associated with pain interference (Table IV, Model 6 and Fig. 2 path b), and the direct effect of post-concussive symptoms was positively associated with pain interference after accounting for the effect of PTSD symptoms (Table IV, Model 6 and Fig. 2 path c’). The indirect effect was calculated as ab = 1.00 × 0.03 = 0.03 and the resulting confidence interval (95% CI = 0.0075–0.0471) did not include zero, suggesting a significant indirect effect of post-concussive symptoms on reported interference from pain through PTSD symptom severity. That is, PTSD symptom severity serves as a partial mediator of the association between perceived post-concussive symptoms and interference from pain.

TABLE IV.

OLS Regression Model Coefficients for BPI Interference

| Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | BPI Interference | CAPS | BPI Interference |

| Constant | 0.57 | 35.92*** | −0.37 |

| NSI | 0.09*** | 1.00*** | 0.06*** |

| CAPS | 0.03** | ||

| R2 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.33 |

Note. All Models contain unstandardized OLS regression coefficients with OLS R2.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

FIGURE 2.

Path coefficients for simple mediation analysis on BPI pain interference. Dotted line denotes the effect of self-reported post-concussive symptoms on pain interference when PTSD symptom severity is included as a mediator. a, b, c, and c’ are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Extant research clearly documents the co-occurrence of TBI and related post-concussive symptoms, PTSD, and pain among Veterans from the OEF, OIF, and OND conflicts as well as the negative consequences of TBI-related post-concussive symptoms and PTSD on pain generally; however less is known about the impact of these symptoms on specific components related to pain (e.g., pain severity). Further, emotional distress negatively impacts both cognitive functioning and pain, but to date, no research has examined the potential mediating role of PTSD on the relationship between post-concussive symptoms and pain. The purpose of the current study was to examine the impact of self-reported post-concussive symptoms on both pain severity and pain interference among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans with PTSD and probable TBI and to evaluate the potential mediating role of PTSD in this relationship. Results from the current study suggest that greater post-concussive symptoms predict greater intensity of the experience of pain, as well as perceived impairment from pain, which replicates and extends previous research in this area.17

Additionally, there was a significant indirect effect of post-concussive symptoms on pain severity and interference through PTSD. In other words, the association between post-concussive symptoms and pain (both severity and interference from pain) appears to be influenced, in part, by PTSD symptoms. Post-concussive symptoms were a significant predictor of PTSD symptoms, which, in turn, significantly predicted greater pain severity or pain interference.

While preliminary, the results of this study provide some insight into the interconnection between these conditions and may have important clinical implications. Previously, Otis et al posited that the high rates of co-occurring TBI, PTSD, and pain in service members from the current conflicts are potentially related to features of the wars that increased exposure to physical and psychological stressors.19 Although the current study cannot speak to the full range of physical stressors endured, findings lend support for the idea that heightened psychological distress may play a key role in continued pain following exposure to head injuries and blasts in a combat zone.

Clinically, these results highlight the importance of fully assessing for PTSD symptoms in Veterans with a history of TBI presenting with pain. In some cases, patients may initially present with a focus on physical complaints related to both pain and experience of TBI. However, given the high rates of comorbidity and the strength of the correlation between symptoms, it is essential to explore symptoms of psychological distress. Further, based on the finding that PTSD symptoms partially mediate the relationship between post-concussive symptoms and pain, it is possible that providing effective PTSD treatment to reduce PTSD severity may provide some benefit in reducing post-concussive and pain symptoms. Additional research is needed to more closely examine this potential relationship. However, previous randomized control trials have supported that perceived pain is reduced in Prolonged Exposure.32

While these results are promising, limitations must be considered. Specifically, post-concussive symptoms were assessed via self-report. While participants reported experiencing an event that may have resulted in a TBI, a full neuropsychological evaluation was not conducted and a confirmation of TBI diagnosis (e.g., via medical record review) or severity (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) was not obtained as part of this study. Additionally, there is some overlap in symptoms included on the NSI and psychological distress.33 Future research incorporating a full neuropsychological evaluation or confirmation of TBI diagnosis and severity would allow for a better understanding of the role of PTSD in the association between TBI and pain. Further, various factor structures of the NSI have been proposed in previous research with the most favorable being a four-factor model (e.g., affective, cognitive, somatosensory, vestibular).34,35 Using different factor solutions of the NSI, as well as incorporating a non-TBI comparison group into future studies would help to minimize the potential impact due to overlap of symptoms. It would also be beneficial for future studies to utilize a larger sample size and additional measures of pain, as the current study utilized only one self-report measure of pain. Another limitation of the present study is that it was cross-sectional and, as a result, no conclusions regarding temporal pattern can be made. For example, it cannot be determined if the pain described was a result of traumatic events or TBIs experienced within the combat deployment or possibly due to some prior injury. Future research should examine the timeline of symptoms which would provide additional information about how these symptoms and experiences may impact the development or maintenance of others.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest a significant indirect effect of TBI symptoms on both pain severity and pain interference through PTSD. PTSD may serve as a link in the relationship between TBI symptoms and experience of pain.

Previous presentation

This work was previously presented as a poster at the Annual Conference of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies in November 2017 in Chicago, IL, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (MRMC; Grant #W81XWH-11-1-0073); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Grant #UL1TR000433). This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ralph H. Johnson VA Medical Center, and VA San Diego Healthcare System.

References

- 1. Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD: An examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40(5): 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Porter KE, Pope EB, Mayer R, Rauch SAM: PTSD and pain: exploring the impact of posttraumatic cognitions in veterans seeking treatment for PTSD. Pain Med 2013; 14(11): 1797–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shipherd JC, Keyes M, Jovanovic T, et al. : Veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: what about comorbid chronic pain? J Rehabil Res Dev 2007; 44(2): 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brennstuhl M, Tarquinio C, Montel S: Chronic pain and PTSD: evolving views on their comorbidity. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2014; 51(4): 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, et al. : Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain diagnoses in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev 2013; 50(9): 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morasco BJ, Lovejoy TI, Lu M, et al. : The relationship between PTSD and chronic pain: mediating role of coping strategies and depression. Pain 2013; 154(4): 609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Defrin R, Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, et al. : Quantitative testing of pain perception in subjects with PTSD – implications for the mechanism of the coexistence between PTSD and chronic pain. Pain 2008; 138(2): 450–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Outcalt SD, Ang DC, Wu JW, et al. : Pain experience of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress. J Rehabil Res Dev 2014; 51(4): 559–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Veterans Health Administration : VHA Handbook 1172.1. Part 2(A), 1 Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Theeler BJ, Erickson JC: Mild head trauma and chronic headaches in returning US soldiers. Headache 2009; 49(4): 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherman KB, Goldberg M, Bell KR: Traumatic brain injury and pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2006; 17(2): 473–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND: Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev 2000; 10: 131–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iverson KM, Hendricks AM, Kimerling R, et al. : Psychiatric diagnoses and neurobehavioral symptom severity among OEF/OIF VA patients with deployment-related traumatic brain injury: A gender comparison. Womens Health Issues 2011; 21(4): S210–S217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanev KS, Pentel KZ, Kredlow MA, Charney ME: PTSD and TBI co-morbidity: scope, clinical presentation and treatment options. Brain Inj 2014; 28(3): 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dolan S, Martindale S, Robinson J, et al. : Neuropsychological sequelae of PTSD and TBI following war deployment among OEF/OIF Veterans. Neuropsychol Rev 2012; 22: 21–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. : Deployment related psychological and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. J Trauma Stress 2015; 28(1): 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stojanovic MP, Fonda J, Fortier CB, et al. : Influence of mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on pain intensity levels in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. Pain Med 2016; 17: 2017–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lew HL, Otis JD, Tun C, et al. : Prevalence of chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and persistent postconcussive symptoms in OIF/OEF veterans: polytrauma clinical triad. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009; 46(6): 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Otis JD, McGlinchey R, Vasterling JJ, Kerns RD: Complicating factors associated with mild traumatic brain injury: Impact on pain and posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2011; 18: 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rauch SAM., Simon NM, Kim HM, et al. : Integrating biological treatment mechanisms into randomized clinical trials: design of PROGrESS (PROlonGed ExpoSure and Sertraline Trial). Contemp Clin Trials 2018; 64: 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwab KA, Ivins B, Cramer G, et al. : Screening for traumatic brain injury in troops returning from deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq: Initial investigation of the usefulness of a short screening tool for traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2007; 22(6): 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cleeland CS. The Brief Pain Inventory. User Guide. Houston, Texas, 2009.

- 23. Cleeland CS, Ryan KM: Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994; 23: 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mendoza T, Mayne T, Rublee D, Cleeland C: Reliability and validity of a modified Brief Pain Inventory short form in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur J Pain 2006; 10: 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blake DD, Weathers F, Nagy LM, et al. : A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behav Ther 1990; 13: 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blake DD, Weathers F, Nagy LM, et al. : The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8: 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cicerone KD, Kalmar K: Persistent postconcussion syndrome: the structure of subjective complaints after mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 1995; 10(3): 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28. King PR, Donnelly KT, Donnelly JP, et al. : Psychometric study of the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012; 49(6): 879–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayes AF: Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 2009; 76: 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 30. MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J: Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar Behav Res 2004; 39: 99–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF: SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004; 36: 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rauch SAM, Favorite T, Giardino N, et al. : Relationship between anxiety, depression, and health satisfaction among Veterans with PTSD. J Affect Dis 2010; 121: 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stein MB, McAllister TW: Exploring the convergence of posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166(7): 768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meterko M, Baker E, Stolzmann KL, et al. : Psychometric assessment of the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory-22: the structure of persistent postconcussive symptoms following deployment-related mild traumatic brain injury among veterans. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2012; 27(1): 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vanderploeg RD, Silva MA, Soble JR, et al. : The structure of postconcussion symptoms on the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory: a comparison of alternative models. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2015; 30(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]