Abstract

Objective:

Despite high rates of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and alcohol-induced deaths among Native Americans, there has been limited study of the construct validity of the AUD diagnostic criteria. The purpose of the current study was to examine the validity of the DSM-5 AUD criteria in a treatment-seeking group of Native Americans.

Methods:

As part of a larger study, 79 Native Americans concerned about their alcohol or drug use were recruited from a substance use disorder treatment agency located on a reservation in the southwestern United States. Participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; SCID-IV-TR) reworded to assess eleven DSM-5 criteria for AUD. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the validity of the AUD diagnostic criteria, and item response theory (IRT) was used to examine the item characteristics of the AUD diagnosis in this Native American sample.

Results:

CFA indicated that a one-factor model of the eleven items provided a good fit of the data. IRT parameter estimates suggested that “withdrawal,” “social/interpersonal problems,” and “activities given up to use” had the highest discrimination parameters. “Much time spent using” and “activities given up to use” had the highest severity parameters.

Conclusions:

The current study provided support for the validity of AUD DSM-5 criteria and a unidimensional latent construct of AUD in this sample of treatment-seeking Native Americans. IRT analyses replicate findings from previous studies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the validity of the DSM-5 AUD criteria in a treatment-seeking sample of Native Americans. Continued research in other Native American samples is needed.

Keywords: Native American, DSM-5, AUD, CFA, IRT

Native American individuals have a higher 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorder (AUD) relative to non-Hispanic white individuals (AUD; 19.2% vs. 14.0%) and are twice as likely to meet criteria for a severe AUD (Grant et al., 2015). They also have higher alcohol-related consequences and morbidity and mortality rates, including alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents and suicides relative to non-Hispanic whites (Center for Disease Control, 2013; Landen et al., 2014). However, it also is important to note the wide variability of alcohol consumption patterns within any ethnic minority group. While lifetime substance use is often lower among Native American groups relative to other adults (Beals et al., 2003; Spicer et al., 2003), of the Native Americans that do consume alcohol, there tends to be increased frequency and severity of use (Grant et al., 2015).

These variations in alcohol consumption and consequences may be associated in part to drinking cultural norms. In a landmark article, MacAndrew and Edgerton (1969) argued that culture influences how people behave during and after drinking alcohol. For example, within group cultural differences have been found based on factors such as religious beliefs (Koenig et al., 2012) and religious commitment (Menagi, et al., 2008). Individuals who identify with religions that promote abstinence generally report higher rates of abstinence; however, those who drink alcohol have an increased risk of AUD (Luczak et al., 2014). Most Southwestern tribes promote abstinence and prohibit alcohol, such that alcohol is illegal to sell, buy, or consume on their reservation land (Kovas et al., 2008). Given the impact of cultural norms and proscriptions against drinking alcohol, cross-cultural applicability of the AUD criteria is warranted.

Only one previous study has examined the construct validity of the AUD criteria in Native Americans. Gilder and colleagues (2011) examined the validity of 10 AUD lifetime symptoms, except for legal concerns, outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) among a Native American community sample that endorsed drinking more than 4 drinks at least once in their lifetime. They found support for a unidimensional construct in this sample suggesting that the abuse and dependence symptoms represent a single diagnosis. “Social and interpersonal problems related to use,” and “tolerance” were associated with lesser severity, whereas “physical and psychological problems related to use” and “activities given up to use” were associated with greater severity. In terms of ability to detect who meets criteria for an AUD and who does not, “social and interpersonal problems related to use” had the highest discrimination ability and “tolerance” had the lowest discrimination ability. Gilder and colleagues did not include the criterion of craving that was added to DSM-5. Thus, to our knowledge, no previous work has examined the construct validity of the full DSM-5 AUD criteria in a treatment-seeking sample of Native Americans.

Most previous factor analytic studies of DSM criteria for AUD replicate the work by Gilder and colleagues (2011), demonstrating that these criteria represent a single continuous latent factor (see review Hasin et al., 2013). These findings also have been incorporated into the newest version of the DSM, 5th edition (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013), in which the alcohol abuse and dependence disorders were combined to reflect a single disorder. Yet, many of the studies used to justify the transition from two disorders in DSM-IV-TR to one disorder in DSM-5 relied on data from predominantly non-Hispanic white samples that were not treatment-seeking. Thus, we found it important to examine the unidimensional nature of the AUD criteria in DSM-5 in a sample of treatment-seeking Native Americans.

Our study builds on previous research in several important ways. One, we are assessing the unidimensional nature of this construct using the DSM-5 rather than the DSM-IV-TR, as previous studies have done. Specifically, the current study included a measure of craving and was testing the validity of this criterion in a diverse sample. Two, although Gilder and colleagues (2011) found support for a single construct in Native Americans, different clinical assessment measures were used. Gilder and colleagues (2011) used the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz, et al., 1994) to assess AUD, whereas the current student assessed AUD using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (First et al., 2002). Lastly, in contrast to Gilder and colleagues (2011), our sample is treatment seeking, and it is currently unclear whether the DSM items are discriminative within those seeking treatment for and meeting diagnostic criteria for AUD as defined by the DSM-5.

The current study used baseline assessment data from a randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of a culturally adapted evidence-based substance use disorder treatment to evaluate the construct validity of the DSM-5 criteria for AUD in a sample of Native Americans seeking treatment for alcohol and drug concerns. Specifically, we sought to test the latent factor structure of the AUD diagnostic criteria and examine item characteristics of the AUD diagnostic criteria using item response theory (IRT). We hypothesized that a single continuous latent factor representing AUD severity would best fit the data in our sample. IRT analyses were exploratory, and we did not have a priori hypotheses for the IRT models.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 79) were recruited from a community treatment center located on a Native American reservation in the southwestern United States. Inclusion criteria into the study were 1) tribal membership, 2) residence within the reservation or immediately contiguous small settlements, 3) aged 18 or older, 4) seeking treatment for a substance use disorder, 5) meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance abuse or dependence for at least one of the following: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, or inhalants, and 6) willing and able to participate (in English) in assessment and treatment procedure of the study.

The majority of participants enrolled in the study were male (n = 54; 68.4%) and had an average age of 32.91 years (SD = 10.134, range = 18–55). Most participants identified as being a member of the tribe (n = 78, 98.7%) and were currently living on the reservation (n = 78, 98.7%). Approximately 64.6% of the participants (n = 51) endorsed tribal-specific religious preference, and 72.2% of the sample (n = 57) reported actively practicing this religious or spiritual preference. On average, participants had completed 11.48 years of education (SD = 0.89), and the largest percentage of participants endorsed being self-employed (43.0%; n = 34). Most participants had received previous treatment for a substance use disorder (69.6%; n = 55)

Measures

Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1990).

Demographic information was obtained using the ASI, a semi-structured interview designed to assess several domains in individuals presenting for substance use concerns. The ASI has been shown to have good reliability and validity (McLellan et al., 1985).

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID-I for DSM-IV-TR) Alcohol Use Module (First et al., 2002).

Past year alcohol abuse and dependence were assessed using the SCID alcohol use disorder module. The SCID alcohol use disorder module is a semi-structured interview that assesses for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence corresponding to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). This measure has demonstrated good reliability, particularly when assessing alcohol abuse and dependence with Kappa values ranging from 0.65–1.0 (Lobbestael et al., 2011; Zanarini et al., 2000).

There was a change in the AUD criteria from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), namely the removal of the legal consequences criterion and addition of the craving criterion. Although the SCID for DSM-IV-TR was used in this study, a supplemental question addressing craving was also included, “(Did you have/have you had) a strong desire or urge to drink?” To assess the validity of the DSM-5 criteria, the legal consequences item was dropped from the analyses and the supplemental craving question was included for a total of 11 criteria. In alignment with DSM-5, alcohol abuse and dependence disorders were combined into a single disorder. Mild (endorsing ≥ 2 criteria), moderate (endorsing ≥ 4 criteria), and severe (endorsing ≥ 6 criteria) sub-classifications also were used.

Procedures

The study was approved by the local university Institutional Review Board and the Tribal Council. Research assistants explained the nature and condition of the study to all eligible participants, and participants signed a statement of informed consent. A federal Certificate of Confidentiality was also obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to protect participant information. As part of a larger randomized trial, participants completed baseline assessment measures before being randomized to a treatment condition. All participants received compensation for the completion of the baseline assessment measures

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed with Mplus (version 7.3; Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Data were treated as binary indicators, such that each participant was coded as either having a criterion present or absent. The SCID (for DSM-IV-TR) is on a 3-point Likert scale with a score of “one” indicating absent, “two” indicating subthreshold, and “three” indicating threshold. All absent and subthreshold indicators were coded as absent, and all threshold scores were coded as present.

Recommendations for sample size in CFA are varied, but a critical sample size of at minimum five cases per parameter is needed (Kline, 2011). The sample size in the current study size meets this minimum requirement with approximately 7.18 cases per parameter. A single latent factor indicated by all 11 AUD criteria items was tested with the latent factor mean set to 0 and variance set to 1 for model identification. The robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation procedure was used to accommodate binary indicators (Li, 2016), and model fit was examined using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; cutoff ≥ 0.90), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; cutoff ≥ 0.90), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; cutoff ≤ 0.08), and weighted root-mean square residual (WRMR; cut-off ≤ 1.00; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu, 2002).

There were missing data on three criteria, failure to fulfill major role obligations, hazardous use, and interpersonal problems, for 16 participants enrolled in the study. WLSMV utilizes pairwise deletion to handle missing data. We also estimated missing data using multiple imputation, and there were no substantive changes in the pattern of results.

Results

Item Descriptive Statistics

Percent endorsement of each AUD criterion are presented in Table 1. In this sample, the “repeated attempts to quit/control use” and “drinking more/longer than planned” criteria were endorsed by almost all individuals in the sample (98% and 96%, respectively). “Much time spent using” and “activities given up to use” were among the least frequently endorsed items (53% and 56%, respectively). Of the 79 participants, 98.73% (n = 78) endorsed at least two criteria. Of participants meeting the DSM-5 diagnostic threshold, 6.41% (n = 5) qualified for a mild AUD, 14.10% (n = 11) for a moderate AUD, and 79.49% (n = 62) for a severe AUD.

Table 1.

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Two-Parameter Probit Item Response Theory Analyses for DSM-5 AUD criteria

| DSM-5 AUD Criteria | % Endorsed |

Factor Loadings |

Item Difficulties |

Item Discriminants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craving | 58.2% | 0.837 | −0.248 | 1.528 |

| Neglected major roles to use | 71.4% | 0.749 | −0.756 | 1.130 |

| Hazardous Use | 84.1% | 0.611 | −1.635 | 0.773 |

| Social/interpersonal problems related to use | 90.5% | 0.855 | −1.531 | 1.651 |

| Drinking more/longer than planned | 96.2% | 0.593 | −2.993 | 0.736 |

| Repeated attempts to quit/control use | 97.5% | 0.213 | −9.166 | 0.218 |

| Much time spent using | 53.2% | 0.806 | −0.099 | 1.363 |

| Activities given up to use | 55.7% | 0.842 | −0.170 | 1.558 |

| Physical/psychological problems related to use |

72.2% | 0.798 | −0.736 | 1.324 |

| Tolerance | 81.0% | 0.522 | −1.682 | 0.612 |

| Withdrawal | 63.3% | 0.887 | −0.383 | 1.921 |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the eleven AUD criteria as indicators of a single latent construct. The model provided an adequate fit of the data [χ2 (44) = 60.219, p = 0.0524; CFI = 0.954; TLI = 0.940; RMSEA = 0.068 (90% CI = 0.000–0.108) p = 0.236; WRMR = 0.908]. This provides evidence of the construct validity of the AUD diagnosis in this population and further suggests that the DSM-5 AUD criteria reflect a unidimensional construct.

Standardized factor loadings for each AUD criterion are presented in Table 1. Results indicated that ten of the eleven criteria loaded strongly and significantly onto the latent factor ranging from 0.522 “tolerance” to 0.887 “withdrawal.” The loading for “repeated efforts to quit/control use” was not significant (β = 0.213, p = 0.125).

Item Response Theory: Item Discrimination and Difficulty

Given that the results from the CFA suggested that the AUD criteria reflect measurement of a single latent trait in this sample of treatment-seeking Native Americans, a two-parameter IRT model was used to further examine the relationship between each criterion and the latent trait. IRT analyses provide information on two main parameters: item discrimination and item difficulty. Discrimination scores are slope parameters. Steeper slopes indicate that a criterion is better able to distinguish between individuals scoring low and high on the AUD latent trait continuum. Difficulty scores are x-coordinate parameters that correspond to a 50% probability of endorsing a criterion. As the difficulty parameter increases, it suggests that an individual needs a higher severity on the latent trait to endorse that criterion at least half of the time.

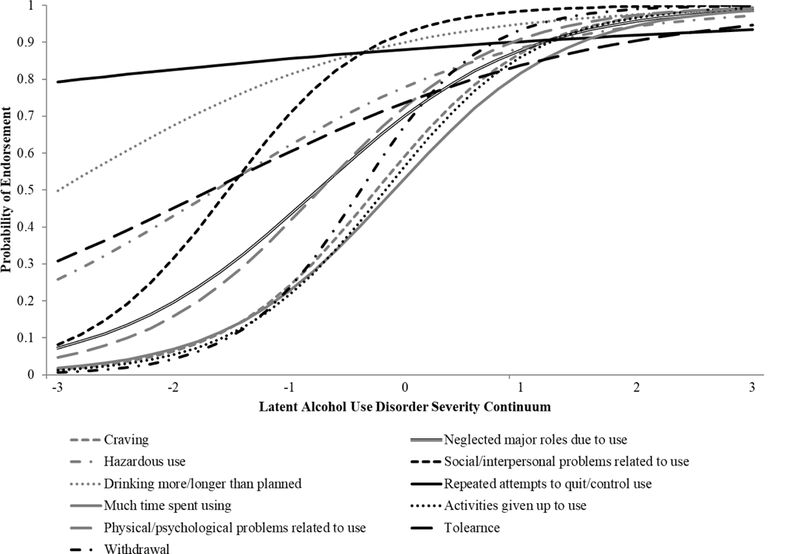

Results from the IRT analyses are presented in Table 1 and item characteristic curves (ICCs) are presented in Figure 1. The largest discrimination scores in the sample were found for “withdrawal,” “social/interpersonal problems related to use,” and “activities given up to use.” The criteria with the lowest discrimination scores were “repeated attempts to quit/control use,” “tolerance,” and “drinking more/longer than planned.” AUD criteria associated with the highest severity scores were “much time spent using” and “activities given up to use.” The lowest severity scores in the sample were “repeated attempts to quit/control use” and “drinking more/longer than planned.”

Figure 1.

Item characteristic curves (ICCs) for DSM-5 alcohol use disorder (AUD) criteria

Discussion

This study is the first to have examined the validity of the DSM-5 AUD criteria in a sample of Native American participants seeking treatment for substance use problems. Confirmatory factor analyses results suggested that an 11-item, one-factor solution was a good fit of these data in this Native American treatment seeking sample. These findings are in line with other research that has identified a one-factor model of the AUD construct across studies (Hasin et al., 2013) and in a Native American community sample (Gilder et al., 2011) albeit with 10 of the current 11 criteria. Furthermore, these findings provide cross-cultural support for the conceptualization of AUD as a single, continuous factor in a treatment seeking sample of Native Americans.

All criteria loaded significantly onto the latent construct except the “repeated attempts to quit/control use” criterion. Other research in treatment seeking samples has also found that this criterion did not load significantly onto a single latent factor (Murphy et al., 2014). Furthermore, this criterion was endorsed by almost all participants in the sample. It could be that this criterion is appropriate for use in discriminating between those with and without AUD but is less informative for treatment seeking individuals. Indeed, Kessler and colleagues (2001) found that endorsing this criterion was associated with increased odds of seeking treatment for an AUD, and Preuss and colleagues (2014) suggested that the “repeated attempts to quit/control use” should be considered to reflect mild AUD in their alternative classification system.

Few studies have examined item difficulty and discrimination scores for DSM-5 AUD criteria in general, and none have examined these parameters in a diverse treatment-seeking sample. The current study suggested that the “withdrawal,” “social/interpersonal problems related to use,” and “activities give up to use,” criteria had the highest discrimination scores, whereas the “repeated attempts to quit/control use,” “tolerance,” and “drinking more/longer than planned” criteria had the lowest discrimination scores. These results are comparable to results from IRT analyses in a non-treatment seeking Native American sample using DSM-IV-TR criteria (Gilder et al., 2011) and in an international sample of individuals who were consuming alcohol using DSM-5 criteria (80.5% of whom met criteria for an AUD; Preuss et al., 2014). In these samples, “social and interpersonal problems related to use” (Gilder et al., 2011; Preuss et al., 2014) and “activities given up to use” (Preuss et al., 2014) had the highest discrimination scores. Similarly, the “tolerance” criterion had the lowest discrimination score (Gilder et al., 2011; Preuss et al., 2014).

In this Native American sample, less severe AUD was represented by “desire to quit/cut down,” “drinking more/longer than planned,” and “tolerance.” These results directly reflect findings from other studies in which these items were also among the easiest to endorse (Gilder et al., 2011; Preuss et al., 2014). More severe AUD, in this Native American sample, was represented by endorsement of the “much time spent using” and the “activities given up to use” criteria, which coincide with results of Preuss and colleagues. In their Native American community sample, Gilder et al. (2011) found that “withdrawal” and “activities given up to use” were associated with greater severity. All the difficulty parameters in the current Native American sample had negative coefficients, which may reflect the fact that all participants in this sample were treatment seeking and most had severe AUD, compared to other studies using non-treatment seeking samples or a survey of individuals who are currently consuming alcohol (Gilder et al., 2011; Hagman, 2017; Preuss et al., 2014).

The results from the IRT analyses suggest potentially useful treatment implications for AUD in this Native American sample. Specifically, many of the items that were most informative with respect to discrimination and severity reflected a narrowing of activities and interpersonal problems related to use. Given these findings, a treatment, such as the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA; Meyers & Smith, 1995) may be a useful intervention. CRA targets relationship happiness and focuses on increasing pleasant reinforcing activities rather than just on stopping alcohol use. Results from an evaluation study and a pilot study suggest the efficacy of the CRA approach in Native American samples (Miller, Meyers, & Hiller-Sturmhöfler, 1999; Venner et al., 2016), and the results from the current study suggest a CRA framework for treatment may also be beneficial and address particularly salient consequences of problematic alcohol use in this sample.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had several limitations. First, the sample size used in this study was small, and included a sample of Native Americans from one tribe in the southwestern United States. Future studies should replicate these findings using larger samples and examine whether these results generalize to other Native American and Indigenous groups. Second, these data relied on self-report recall of alcohol-use and alcohol-related problems over the past year, which may be subject to recall bias. Third, this study used an adapted version of the SCID for DSM-IV-TR to assess for DSM-5 criteria. Future studies should continue to assess the validity of the SCID for DSM-5 in diverse groups. However, in the current study, the wording used in the different versions of the SCID was quite similar, the craving criterion was assessed using almost identical prompts, and a comparable procedure was used in previous studies to help advise and test proposed changes made in the diagnostic criteria for AUD from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 (Borges et al., 2011).

Conclusions

The current study provides preliminary support for the validity of the DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria as a single continuum in a sample of Native Americans seeking treatment for substance use concerns. Additionally, this is the first study to examine the DSM-5 AUD criteria using IRT analyses in a diverse sample of treatment seeking individuals. These findings suggest that “social and interpersonal problems related to use” and “activities give up to use” may be more informative criteria for assessing AUD severity in treatment seeking Native American samples, whereas “repeated attempts to quit/control use” and “drinking more/longer than planned” may be less informative. Future research with other Native American and Indigenous populations will shed light on the cross-cultural applicability of the DSM-5 AUD diagnostic criteria and may highlight important cultural considerations in conceptualization, measurement, and treatment of AUD.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Katie Witkiewitz, Ph.D., for her assistance with data analysis and for her helpful comments on a pre-submission draft of this paper.

This research was supported by a grant (R01 DA021672) awarded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of NIDA.

Footnotes

Dr. Kamilla Venner has a financial conflict of interest due to her consulting activities and has an active FCOI management plan at the UNM.

Contributor Information

Kelsey N. Serier, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico

Kamilla L. Venner, Department of Psychology, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, & Addictions, University of New Mexico

Ruth E. Sarafin, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico

References

- American Psychiatric Association; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Revised 4th Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Manson SM, AI-SUPERPFP Team. Racial disparities in alcohol use: Comparison of 2 American Indian reservation populations with national data. Am J Public Health 2003; 93:1683–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Threshold and optimal cut‐points for alcohol use disorders among patients in the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011; 35-1270–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI Jr., Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol 1994; 55:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 162:1–187. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Gizer IR, Ehlers CL. Item response theory analysis of binge drinking and its relationship to lifetime alcohol use disorder symptom severity in an American Indian community sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011; 35: 984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72, 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman BT. Development and psychometric analysis of the Brief DSM–5 Alcohol Use Disorder Diagnostic Assessment: Towards effective diagnosis in college students. Psychol Addict Behav 2017; 31:797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170: 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999; 6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Berglund PA, et al. (2001). Patterns and predictors of treatment seeking after onset of a substance use disorder. Arch Gen Psychiat 2001; 58:1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: The Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, King D, Carson VB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kovas AE, McFarland BH, Landen MG, Lopez AL, May PA. Survey of American Indian alcohol statutes, 1975–2006: Evolving needs and future opportunities for tribal health. J Study Alcohol Drug 2008; 69:183–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landen M, Roeber J, Naimi T, Nielsen L, Sewell M. Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska natives in the United States, 1999–2009. Am J Public Health 2014; 104:S343–S349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods 2016; 48: 936–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter‐rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) and Axis II disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother 2011; 18:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luczak SE, Prescott CA, Dalais C, Raine A, Venables PH, Mednick SA. Religious factors associated with alcohol involvement: Results from the Mauritian Joint Health Project. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 133:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAndrew C, Edgerton RB. Drunken Comportment: A Social Explanation. Oxford: Aldine, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New Data from the Addiction Severity Index Reliability and Validity in Three Centers. J Nerv Ment Dis 1985; 173:412–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Parikh G, Bragg A, Cacciola J, Fureman B, Incmikoski R. Addiction Severity Index Administration Manual. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Veterans’ Administration Center for Studies of Addiction, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Menagi FS, Harrell ZA, June LN. Religiousness and college student alcohol use: Examining the role of social support. J Religion Health 2008; 47:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Smith JE. Clinical Guide to Alcohol Treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. New York: Guildford Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Meyers RJ, Hiller-Sturmhöfler S.The Community Reinforcement Approach. Alcohol Res Health 1999; 23:116–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Stojek MK, Few LR, Rothbaum AO, MacKillop J. Craving as an alcohol use disorder symptom in DSM-5: an empirical examination in a treatment-seeking sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2014; 22: 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide, 7thLos Angeles, CA:Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Watzke S, Wurst FM. Dimensionality and stages of severity of DSM-5 criteria in an international sample of alcohol-consuming individuals. Psychol Med 2014; 44:3303–3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer P, Beals J, Croy CD, Mitchell CM, Novins DK, Moore L, Manson SM. The prevalence of DSM‐III‐R alcohol dependence in two American Indian populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003; 27:1785–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Greenfield BL, Hagler KJ, et al. Pilot outcome results of culturally adapted evidence-based substance use disorder treatment with a Southwest Tribe. Addict Behav Rep 2016; 3:21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CY. Evaluation Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. J Pers Disord 2000; 14:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]