Abstract

Background:

Economic conditions affect surgical volumes, particularly for elective procedures. In this study, we aimed to identify the effects of the 2008 US economic downturn on hand surgery volumes to guide surgeons and managers when facing future economic crises.

Methods:

We used the California State Ambulatory Surgery and Services Databases from January 2005 to December 2011, which includes the entire period of the Great Recession (December 2007 to June 2009). We abstracted the monthly volume of five common hand procedures using ICD-9 and CPT codes. Pearson’s statistics were used to identify the correlation between unemployment rate and surgical volume for each procedure.

Results:

The total number of operative cases was 345,583 during the study period of seven years. Most common elective hand procedures, such as carpal tunnel release and trigger finger release had a negative correlation with the unemployment rate, but the volume of distal radius fracture surgery did not show any correlation. Compared with carpal tunnel release (r = −0.88) or trigger finger release volumes (r = −0.85), thumb arthroplasty/arthrodesis volumes (r = −0.45) showed only a moderate correlation.

Conclusions:

The economic downturn decreased elective hand procedure surgical volumes. This may be detrimental to small surgical practices that rely on revenue from elective procedures. Taking advantage of the principle that increased volume reduces unit cost may mitigate the lost revenue from these elective procedures. In addition, consolidating hand surgery services at larger, regional centers may reduce the effect of the economic environment on individual hand surgeons.

The Great Recession was a time of economic instability in the US taking place between December 2007 and June 2009.1 The Recession affected spending patterns in the medical field in addition to general patterns of consumer spending, resulting in reduced diagnostic rates, frequency of physician visits, and amounts of medication used.2–6 These trends have been studied with a focus on surgical volume in a number of different specialties, including cosmetic surgery and adult joint reconstructive surgery.7–11 Most studies have shown that surgical volumes decreased with economic downturn, particularly for elective rather than emergency procedures.

Putter et al. reported that hand and wrist injuries were the third most expensive and frequent type of injury, after lower limb and hip injuries.12 Additionally, Silverstein et al. reported that average claims per patient for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) in Washington state totaled $18,458 and resulted in 102 lost workdays.13 Also, Foley et al. reported that the estimated annual total loss of earnings for patients with CTS in Washington state totaled $197M to $382M in 2007.14 Despite the substantial economic burden, the effects of an economic downturn have not been adequately described in the field of hand surgery. Using data from a single institution, Gordon et al. reported that the number of carpal tunnel releases (CTRs) performed by orthopedic surgeons decreased during times of economic downturn.15 However, to our knowledge, a study using a large database or analyzing a variety of hand conditions has not been conducted. In this study, we identify the effects of the 2008 Recession on the surgical treatment volumes of five common hand conditions, and hypothesize that volumes for elective hand surgery procedures, such as CTRs, will correlate with the economy because people may postpone their surgical treatment when economic conditions are uncertain.

Methods

Database

We obtained data from the California State Ambulatory Surgery Database (SASD) of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) from January 2005 to December 2011, which includes the entire period of the Great Recession (December 2007 - June 2009), and abstracted the monthly volumes of five common hand procedures. The database is created and maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the data includes information on all payments, costs, and practice patterns for encounter-level data for all outpatient services. 16

Study Samples and Variables

We selected the five most frequently performed hand surgery procedures in the California State Ambulatory Surgery and Services database. In order of descending frequency, they were: carpal tunnel release (CTS), trigger finger release (TF), cubital tunnel release (CuTS), distal radius fracture (DRF), and surgery for arthritis of the basilar joint of the thumb (CMC-OA). All of these conditions, except for DRF, are chronic hand conditions. In general, surgical treatment for chronic conditions, including CTS, TF, CuTS and CMC-OA is elective. However, because DRF is an acute traumatic condition, thereby requiring treatment, we expect its surgical volume not to be affected by the economic environment.

We extracted claims from the databases using ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) diagnosis codes indicating the five common hand conditions listed above (CTS: 354.0; TF:727.03, 727.05, and 727.00; CuTS: 354.2; DRF: 813.40 to 42, and 813.44 to 45; CMC-OA: 715.00 to 719.99; See Appendix 1). We excluded open distal radius fractures because they always require surgical treatment. Then, we filtered for claims with CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) operative codes for procedures used to treat the identified conditions (CTS: 29848 and 64721; TF: 26055, 26145, 25110 and 26160; CuTS: 24301, 24350, 24358, 24359 and 64718; DRF: 20690, 20692, 25606–25609, 25611 and 25620; CMC-OA: 25210, 25445, 25447, 26841, and 26842; See Appendix 1).17–20 We also abstracted yearly data on payment type for each procedure (Medicare, Medicaid, standard insurance, self-pay, and Worker’s Compensation and others (including CHAMPUS, CHAMPVA, Title V, and other government programs). These are the five hand conditions are most often covered by Worker’s Compensation.12,21 We used the unemployment rate as an indicator for national economic health based on methods used by other similar papers found in our literature review.5,22,23 The unemployment rate is also used as an indicator for macro-economic health in economic research. The monthly unemployment rate was obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.1

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine monthly and annual procedural volumes between 2005 and 2011. We estimated the association between unemployment rate and the volume of the five procedures by using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Moreover, we wanted to know if the association would be different after the Great Recession, so we estimated the association between unemployment rate and the procedural volume before and after 2007. Additionally, because payment types may be another factor that influences volume, we examined the annual percentage of procedures using each payment type. All statistical tests were 2-sided and performed at a 5% level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

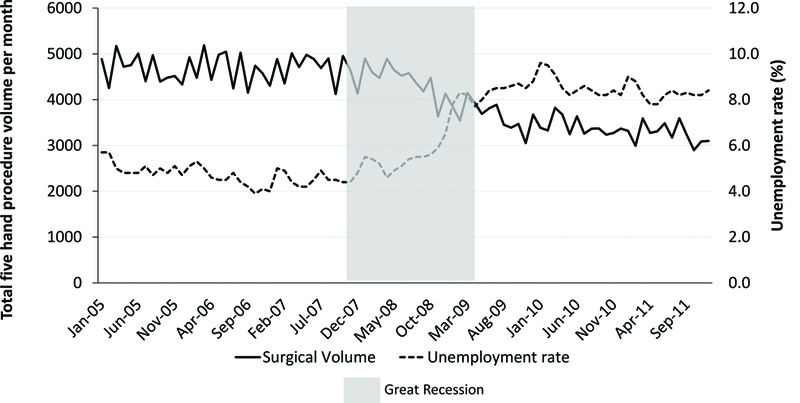

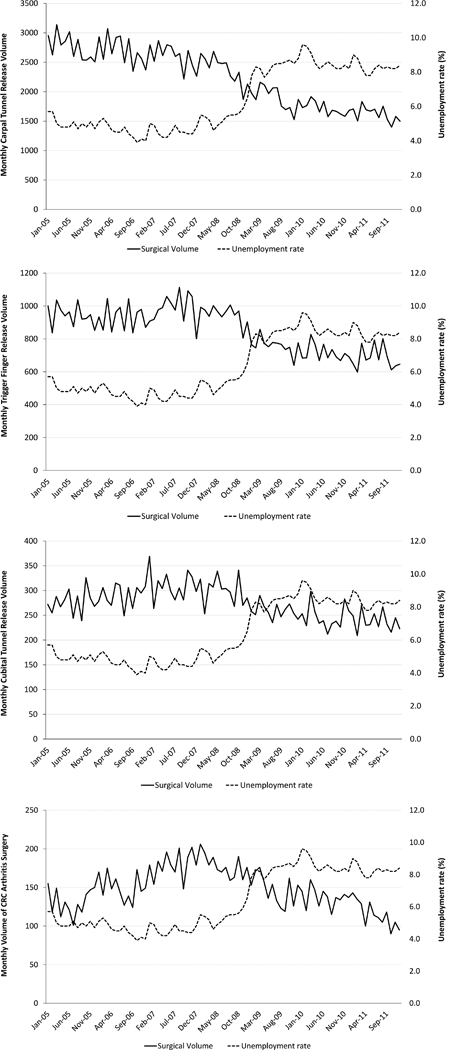

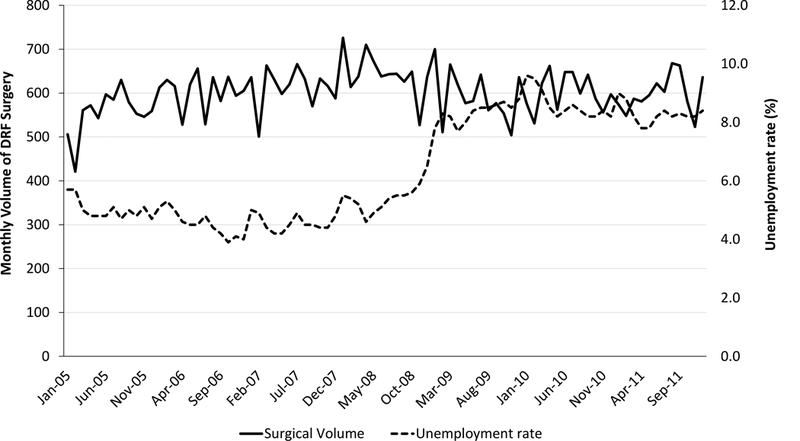

The total number of the operative cases was 345,583 (CTS: n = 187,971; TF: n =71,605; DRF: n = 50,515; CuTS: n = 23,050; CM-OA: n = 12,439) during the study period of 2005 to 2011. The economic downturn had a substantial effect on hand surgical volumes in California (Figure 1). The number of carpal tunnel releases declined from 2,953 per month in Jan 2005 to 1,499 per month in Dec 2011 with its lowest monthly volume being 1,399 in September 2011 (Table 1, Figure 2a). The other monthly procedural volumes ranged from 1,113 (Aug, 2007) to 598 (Feb, 2011) for trigger finger release (Figure 2b), 369 (Jan, 2007) to 209 (Feb, 2011) for cubital tunnel release (Figure 2c), 206 (Jan, 2008) to 90 (Oct, 2011) for arthrodesis or arthroplasty for CMC osteoarthritis (Figure 2d), and 421 (Feb, 2005) to 726 (Jan, 2007) for surgical treatment of closed distal radius fracture.

Figure 1. The relationship between the cumulative total of all five hand procedural volumes and the unemployment rate.

The U.S. unemployment rate shows an inverse correlation with the procedural volumes of five common hand procedures in California.

Table 1. The relationships between unemployment rate and hand procedure volumes.

Blue background showing the relationships between the unemployment rate and procedural volumes (correlation coefficient 0.2~1.0).

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Release | Trigger Finger Release | Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Release | Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Carpometacarpal Joint of the Thumb | Distal Radius Fracture Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total procedures | 187,971 | 71,605 | 23,050 | 12,439 | 50,515 |

| Mean volume during study period | 2237.8 | 852.4 | 148.1 | 274.4 | 601.4 |

| Median volume during study period | 2297 | 852 | 147 | 270 | 604 |

| Minimum volume during study period | 1399 (Sep, 2011) |

598 (Feb, 2011) |

90 (Oct, 2011) |

209 (Feb, 2011) |

421 (Feb, 2005) |

| Maximum volume during study period | 3137 (Mar, 2005) |

1113 (Aug, 2007) |

206 (Jan, 2008) |

369 (Jan, 2007) |

726 (Jan, 2008) |

|

Correlation with unemployment (P Value) |

−0.88178†† (<.0001) |

−0.8547†† (<.0001) |

−0.68287† (<.0001) |

−0.45236† (<.0001) |

−0.09365 (0.3968) |

Negative relationships (<−0.7~0.9),

Fairly negative relationships (−0.7~−0.4)

Figure 2. Monthly chronic hand surgery volumes during the study period.

All chronic hand condition volumes showed an inverse correlation with the U.S. unemployment rate.

Figure 2a. Monthly carpal tunnel release volume.

Figure 2b. Monthly trigger finger release volume.

Figure 2c. Montly cubital tunnel release volume.

Figure 2d. Monthly volume for surgery for osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb.

The monthly procedural volumes were compared to the monthly US unemployment rate (Table 1). CTS, TF, CuTS, and CMC-OA procedural volumes showed an inverse correlation with the unemployment rate. Chronic conditions, such as CTS and CuTS, showed relatively strong relationships with the economic indicators (r = −0.88 and −0.68), whereas CMC-OA procedural volume showed a weaker relationship (r = −0.45). However, DRF, which was the only acute condition among the study samples, did not show any statistical relationships with the indicator. Compared with the other procedures (Figure 2), the DRF treatment volume was quite stable throughout the study period (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Monthly surgical volume for distal radius fractures during the study period.

DRF volume was quite stable. It showed no statistical relationship with the U.S. unemployment rate.

Among the chronic conditions that showed the strongest relationships with the economic indicator (CTS and CuTS), we conducted subgroup analyses. These volumes were considered in relation to the US unemployment rate before and after the Great Recession occurred, and found that the economic indicator showed much stronger relationships with procedural volumes after the recession occurred (Table 2). This means the chronic, elective hand surgery volumes become more sensitive to the US economy during periods of economic recession.

Table 2. The relationships between chronic hand procedure volumes and unemployment rate before and after start of the Great Recession.

Blue background showing the relationships between the economic indicator and procedural volumes (correlation coefficient 0.2~1.0).

| Before Dec 2007 | After Dec 2007 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | P Value | Correlation | P Value | |

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | 0.18277 | 0.3087 | −0.82764†† | <.0001 |

| Trigger Finger | −0.33751 | 0.0547 | −0.8194†† | <.0001 |

| Cubital Tunnel Syndrome | −0.39905 | 0.0214 | −0.70606†† | <.0001 |

| Osteoarthritis of the Carpometacarpal Joint of the Thumb | −0.37266 | 0.0327 | −0.67326† | <.0001 |

Negative relationships (<−0.7),

Fairly negative relationships (−0.7~−0.4)

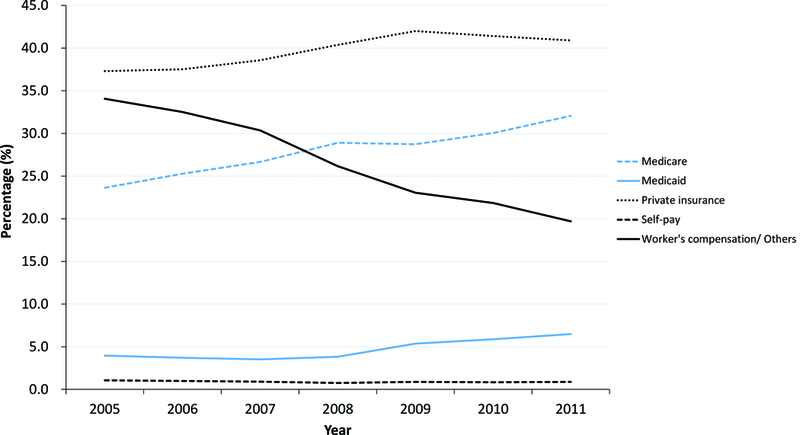

The annual rate of payment types for all study samples are shown in Appendix 2. The overall trends in transactions were quite similar among the conditions, represented by carpal tunnel release payment transition (Figure 4). During the study period of 2005 to 2011, Medicare (23.6% to 32.1%, 8.5% increase for CTS) and Medicaid (4.0% to 6.5%, 2.5% increase for CTS) payments gradually increased, whereas worker’s compensation/others (34.1% to 19.7%, 14.4% decrease for CTS) payments decreased for CTS.

Figure 4. The types of payment used to pay for carpal tunnel release.

Medicare and Medicade payment gradually increased, while Worker’s compensation/ Others payment types decreased during the study period.

Discussion

Macro-economic events have a far larger impact on the field of hand surgery than previously thought.12–14,24 In this study we found that, in California, most common hand procedural volumes correlated significantly with the unemployment rate, which can be used to estimate the macro-economic environment. Although the average surgical cost of these procedures is relatively low, a major change in volume can affect surgical revenue. DRF surgery was an exception. Despite the possibility that, in some cases, patients could have opted for cheaper conservative treatment over open reduction volume, DRF surgical procedures did not show a significant statistical relationship with the economic conditions. This indicates that surgical volumes for acute traumatic conditions may have some degree of economic resistance.

The degree to which the Recession affected elective hand procedures was not consistent across conditions. CMC-OA procedural volume was less affected by economic decline compared with the other chronic conditions, despite its higher than average surgical cost. We hypothesize that this may be because surgery for CMC-OA had the highest proportion of patients on Medicare. Because patients must be over the age of 65 to qualify for Medicare coverage, this procedure would have also most likely had the highest proportion of retirees who are largely unaffected by unemployment rates. In contrast, conditions such as CTS or CuTS often develop in relatively younger individuals. At times of economic downturn, young people especially those who are working in manual labor may have insurance with higher out-of-pocket costs or that is not as widely-accepted. This may contribute to the strong correlation demonstrated with those procedures.

This is consistent with findings for other procedures. For example, Klein et al. reported in his research that out-of-pocket cost was the main reason for cancellation of total joint replacement surgery during the Great Recession.9 In addition, Ennis et al. reported that critical care such as cancer treatment may delayed or ignored for financial reasons.5

Delays in treatment can have deleterious impacts on productivity and individual workers’ health.5,25 For example, postponing the surgical treatment of a nerve compression disorder may lead to the inability to perform of manual labor and irreversible nerve damage. Foley et al.26 reported in his research that CTS patients had decreased productivity and musculoskeletal functions for at least 6 years, and several studies have shown that early diagnosis and treatment intervention without financial concerns can reduce the return to work period.27–29 Ensuring the availability of affordable, widely-accepted health insurance can reduce treatment delays in all areas of medicine. Potentially also contributing to treatment delays, we found that the use of worker’s compensation gradually declined during the study period. This may indicate that employees are less likely to pursue treatment for a work-related condition for fear of lost productivity and potential income. This may be in part because of the difficulty of attributing chronic hand conditions to work duties. Chronic hand condition, such as CTS, appear over time rather than immediately after a single traumatic incident in acute cases such as DRF. Additionally, daily activities can also exacerbate chronic work-related conditions, causing further difficulty in proving they are work-related and therefore eligible for worker’s compensation. Recognizing this, local, state, and federal agencies should enforce existing policies, and encourage early treatment intervention using worker’s compensation for these chronic work-related hand conditions, particularly during times of economic instability.

From a health system perspective, reduced revenue can be mitigated by taking advantage of the principle that increased volume reduces unit cost. Concentrating procedures at high-volume centers or even high-volume surgeons can substantially reduce per procedure costs. Individual hand surgeons may find it prudent to coordinate with other nearby surgeons in order to bring the field a degree of economic resistance and reduce possible losses from economic instability or downturn. This principle has been demonstrated in a variety of plastic and orthopaedic surgery procedures. Regionalization further benefits patients by taking advantage of the widely-reported association between surgical volume and surgical quality.30 This teamwork and regionalization will not only mitigate the effect of economic downturns, but also works towards the triple aim of improving patient experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care put forth by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.31

There were several limitations in this study. First, chronic hand conditions, represented by CTS, are largely caused by work-related activities; it is possible that the decrease in surgical volume was because of unemployment itself. In other words, fewer individuals are experiencing work-related CTS because fewer individuals are employed. Second, we have not established the exact relationships between economic downturn and hand surgery procedures, and, instead, have used Pearson’s correlation statistics to evaluate associations between the monthly volume of surgical procedure and economic indicators. Other factors, such as the Affordable Care Act, passed very shortly after the Recession, or related health care legislation, may have affected procedural volume as well. Third, trends in surgical treatment may have changed during the study period, such as the increasing use of volar locking plate for DRF treatment since it was introduced in 2000.32,33 The change might affect the surgical indication itself, leading surgical volume to changes. Third, the SASD database only includes outpatient claims. This means that some inpatient data, such as information on patients with severe comorbidities or multiple injuries were not included in this study.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides a sound analysis of the effect of economic downturn on common hand surgery procedural volumes using the unemployment rate as a macro-economic indicator. We found a significant relationship between hand surgery volumes and the unemployment rate, especially among elective treatment for chronic hand conditions. Policy-makers and health system managers should recognize these trends and plan accordingly for times of economic decline. However, there is still room to examine the relationship between the economy and hand surgery volumes. Therefore, further research is required to evaluate exactly how much financial loss is occurring so as to reconsider future resource distribution.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure Statement: This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 2 K24-AR053120–06. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, it was funded by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (project CORPG3G0111 and CORPG3G0161).

Appendix 1. Diagnosis and Procedure Codes for Case Selection and Identification

| Diagnosis and Procedure Codes | |

|---|---|

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | |

| Diagnosis Code | 354.0 |

| Procedure Code | 29848, 64721 |

| Trigger Finger | |

| Diagnosis Code | 727.03, 727.05, 727.00 |

| Procedure Code | 26055, 26145, 25110, 26160 |

| Cubital Tunnel Syndrome | |

| Diagnosis Code | 354.2 |

| Procedure Code | 24301, 24350, 24358, 24359, 64718 |

| Osteoarthritis of the Carpometacarpal Joint of the Thumb | |

| Diagnosis Code | 715.00, 715.04,715.09, 715.10, 715.14, 715.80, 715.89, 715.90, 715.94, 716.60, 716.64, 716.90, 716.94, 716.99, 718.00, 718.04, 718.09, 718.80, 718.84, 718.89, 718.90, 718.94, 718.99, 719.40, 719.44, 719.49, 719.50, 719.54, 718.59, 719.60, 719.64, 719.69, 719.90, 719.94, 719.99 |

| Procedure Code | 25210, 25445, 25447, 26841, 26842 |

| Distal Radius Fracture | |

| Diagnosis Code | 813.40, 813.41, 813.42, 813.44, 813.45 |

| Procedure Code | 20690, 20692, 25606, 25607, 25608, 25609, 25611, 25620 |

Appendix 2. The Rate of Payment Types for All Study Samples

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Medicare | 23.63 | 25.28 | 26.66 | 28.90 | 28.73 | 30.04 | 32.05 |

| Medicaid | 3.96 | 3.71 | 3.51 | 3.82 | 5.36 | 5.87 | 6.48 |

| Private insurance | 37.30 | 37.52 | 38.57 | 40.37 | 41.99 | 41.41 | 40.90 |

| Self-pay | 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| Worker’s compensation/ Others | 34.05 | 32.51 | 30.35 | 26.16 | 23.04 | 21.84 | 19.69 |

| Trigger Finger | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Medicare | 26.11 | 27.34 | 27.61 | 30.19 | 29.28 | 30.50 | 31.19 |

| Medicaid | 3.07 | 2.84 | 3.15 | 2.76 | 4.38 | 4.68 | 5.03 |

| Private insurance | 48.39 | 47.97 | 48.71 | 48.69 | 50.10 | 49.72 | 49.78 |

| Self-pay | 1.10 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 1.05 | 0.75 |

| Worker’s compensation/ Others | 21.33 | 21.10 | 19.86 | 17.71 | 15.40 | 14.05 | 13.24 |

| Cubital Tunnel Syndrome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Medicare | 17.09 | 17.37 | 18.67 | 20.70 | 20.72 | 21.58 | 22.72 |

| Medicaid | 2.86 | 2.95 | 2.34 | 3.39 | 4.12 | 4.53 | 5.86 |

| Private insurance | 37.73 | 41.23 | 39.98 | 42.12 | 46.24 | 47.01 | 47.02 |

| Self-pay | 1.02 | 1.26 | 1.18 | 1.11 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.81 |

| Worker’s compensation/ Others | 41.29 | 37.18 | 37.83 | 32.69 | 28.06 | 25.73 | 23.60 |

| Osteoarthritis of the Carpometacarpal Joint of the Thumb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Medicare | 29.09 | 30.97 | 31.88 | 30.15 | 33.11 | 34.41 | 34.08 |

| Medicaid | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 1.13 | 1.58 | 2.33 |

| Private insurance | 46.15 | 47.91 | 48.14 | 50.75 | 48.36 | 49.06 | 48.47 |

| Self-pay | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.73 |

| Worker’s compensation/ Others | 22.98 | 19.61 | 18.68 | 17.56 | 16.61 | 14.41 | 14.39 |

| Distal Radius Fracture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

| Medicare | 22.78 | 22.90 | 22.60 | 24.84 | 24.31 | 25.78 | 26.05 |

| Medicaid | 5.82 | 6.02 | 5.81 | 6.54 | 8.00 | 8.13 | 8.31 |

| Private insurance | 53.67 | 53.70 | 54.51 | 53.52 | 52.51 | 50.98 | 48.93 |

| Self-pay | 5.68 | 5.34 | 6.16 | 5.32 | 5.91 | 5.63 | 6.73 |

| Worker’s compensation/ Others | 12.06 | 12.05 | 10.92 | 9.77 | 9.27 | 9.47 | 9.97 |

References

- 1.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: https://www.bls.gov AA, 2017.

- 2.Suhrcke M, Stuckler D, Suk JE, et al. The impact of economic crises on communicable disease transmission and control: a systematic review of the evidence. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2011;6(6):e20724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin-Moreno JM, Anttila A, von Karsa L, Alfonso-Sanchez JL, Gorgojo L. Cancer screening and health system resilience: keys to protecting and bolstering preventive services during a financial crisis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2212–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modrek SP, Hamad RMD, Cullen MRMD. Psychological Well-Being During the Great Recession: Changes in Mental Health Care Utilization in an Occupational Cohort. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(2):304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ennis KY, Chen MH, Smith GC, et al. The Impact of Economic Recession on the Incidence and Treatment of Cancer. J. 2015;6(8):727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Thomas SB. Using quantile regression to examine health care expenditures during the Great Recession. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):705–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson SCBA, Soares MAMD, Reavey PLMDMS, Saadeh PBMD. Trends and Drivers of the Aesthetic Market during a Turbulent Economy. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2014;133(6):783e–789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iorio R, Davis CM 3rd, Healy WL, Fehring TK, O’Connor MI, York S. Impact of the economic downturn on adult reconstruction surgery: a survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein GR, Parcells BW, Levine HB, Dabaghian L, Hartzband MA. The economic recession and its effect on utilization of elective total joint arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(11):499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo IC. Trends in refractive surgery at an academic center: 2007–2009. BMC ophthalmol. 2011;11:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon CR, Pryor L, Afifi AM, et al. Cosmetic surgery volume and its correlation with the major US stock market indices. Aesthet. 2010;30(3):470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Putter CE, Selles RW, Polinder S, Panneman MJ, Hovius SE, van Beeck EF. Economic impact of hand and wrist injuries: health-care costs and productivity costs in a population-based study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(9):e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverstein B AD. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, back and upper extremity in Washington State, 1997–2005 Safety and Health Assessment and Research for Prevention (SHARP) Washington State Department of Labor and Industries; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foley M, Silverstein B, Polissar N. The economic burden of carpal tunnel syndrome: long-term earnings of CTS claimants in Washington State. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(3):155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon CR, Pryor L, Afifi AM, et al. Hand surgery volume and the US economy: is there a statistical correlation? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65(5):471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HCUP User Support (HCUP-US). SASD Over view. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sasdoverview. April 14.

- 17.Sears ED, Swiatek PR, Chung KC. National Utilization Patterns of Steroid Injection and Operative Intervention for Treatment of Common Hand Conditions. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(3):367–373 e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adkinson JM, Zhong L, Aliu O, Chung KC. Surgical Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: Trends and the Influence of Patient and Surgeon Characteristics. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(9):1824–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aliu O, Davis MM, DeMonner S, Chung KC. The influence of evidence in the surgical treatment of thumb basilar joint arthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(4):816–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giladi AM, Shauver MJ, Ho A, Zhong L, Kim HM, Chung KC. Variation in the incidence of distal radius fractures in the U.S. elderly as related to slippery weather conditions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Occupational and work-related diseases Available at: http://www.who.int April 14.

- 22.Sharma V, Zargaroff S, Sheth KR, et al. Relating Economic Conditions to Vasectomy and Vasectomy Reversal Frequencies: a Multi-Institutional Study. Journal of Urology. 2014;191(6):1835–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourdon E, Schüller K, Stühlinger W. The impact of economic recession on the use of treatment technology for peripheral arterial disease. Health Policy and Technology. 2015;4(1):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alderman AK, Storey AF, Chung KC. Financial impact of emergency hand trauma on the health care system. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(2):233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurfinkel EP, Bozovich GE, Dabbous O, Mautner B, Anderson F. Socio economic crisis and mortality. Epidemiological testimony of the financial collapse of Argentina. Thromb J. 2005;3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foley M, Silverstein B. The long-term burden of work-related carpal tunnel syndrome relative to upper-extremity fractures and dermatitis in Washington State. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(12):1255–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniell WE, Fulton-Kehoe D, Franklin GM. Work-related carpal tunnel syndrome in Washington State workers’ compensation: utilization of surgery and the duration of lost work. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(12):931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz JN, Keller RB, Fossel AH, et al. Predictors of return to work following carpal tunnel release. Am J Ind Med. 1997;31(1):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kho JY, Gaspar MP, Kane PM, Jacoby SM, Shin EK. Prognostic Variables for Patient Return-to-Work Interval Following Carpal Tunnel Release in a Workers’ Compensation Population. Hand (New York, NY). 2017;12(3):246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(15):1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barry JY, McCrary HC, Kent S, Saleh AA, Chang EH, Chiu AG. The Triple Aim and its implications on the management of chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016;30(5):344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nellans KW, Kowalski E, Chung KC. The epidemiology of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2012;28(2):113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waljee JF, Zhong L, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. The influence of surgeon age on distal radius fracture treatment in the United States: a population-based study. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(5):844–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]