Abstract

Purpose:

There is presently an ongoing debate on the relative merits of suggested criteria for spirometric airway obstruction. This study tests the null hypothesis that no superiority exists with the use of fixed ratio (FR) of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7 versus less than lower limit predicted (LLN) criteria with or without FEV1 <80% predicted in regards to future mortality.

Methods:

In 1988–1994 the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) measured FEV1 and FVC with mortality follow-up data through December 31, 2011. For this survival analysis 7472 persons aged 40 and over with complete data formed the analytic sample.

Results:

There were a total of 3554 deaths. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression revealed an increased hazard ratio in persons with both fixed ratio and lower limit of normal with a low FEV1 (1.79, p < 0.0001), in those with fixed ratio only with a low FEV1 (1.77, p < 0.0001), in those with abnormal fixed ratio only with a normal FEV1 (1.28, p < 0.0001) compared with persons with no airflow obstruction (reference group). These remained significant after adjusting for demographic variables and other confounding variables.

Conclusions:

The addition of FEV1 < 80% of predicted increased the prognostic power of the fixed ratio <0.7 and/or below the lower limit of predicted criteria for airway obstruction.

Keywords: Spirometry, Pulmonary disease, Chronic obstructive, Mortality, Survival analysis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prominent non-communicable disease globally because of its high prevalence and associated economic costs.1 Since 1980 among persons aged 65 and over, COPD has risen from the fifth to the third leading cause of death in the US. The inhalation of noxious particles and gases, mostly through tobacco smoking, is the main risk factor for COPD, which is characterized by inflammation and abnormal lung aging with airflow obstruction.2 The prevalence of COPD increases with age.3

Current COPD guidelines recommend the use of a low ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) to establish the diagnosis in patients with chronic respiratory symptoms or those at risk. There is presently an ongoing debate on the relative merits of suggested criteria for spirometric airflow obstruction confirmation. Some criteria involve the use of a fixed ratio of the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.7 in addition to a low FEV1, a value set at less than 80% of predicted. The second criterion involves the use of a FEV1/FVC ratio below the lower limit of predicted/normal (LLN). Although there have been many cross-sectional studies comparing the use of these criteria on clinical outcomes, few studies comparing the effect of the criteria on mortality have appeared. Therefore, this study tested the null hypothesis that no difference exists among these criteria in regards to predicting mortality with or without the addition of the FEV1.

METHODS

Participants

The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) was conducted in 1988–1994 on a nationwide, multi-stage, probability sample of about forty thousand persons from the civilian, non-institutionalized population aged 2 months and over of the United States excluding reservation lands of American Indians. Details of the survey plan, sample design, operations and response rates have been published as have procedures used to obtain IRB approval and informed consent and to maintain confidentiality of information obtained.4 Public-use data sets and documentation for NHANES III were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/).

Measures of exposure

Data on the following measures of exposure in NHANESIII were collected as follows: All adults in NHANES III were offered a pulmonary function test, and protocols for these measurements have been detailed previously.5,6 Participants were excluded for the following reasons: self-reported chest or abdominal surgery within the previous 3 weeks and hospitalization for a heart problem within the previous 6 weeks. NHANES III attempted as many as eight maneuvers with the goal of obtaining five acceptable maneuvers. Spirometry was performed in 20,627 survey participants (16,484 adults and 4143 youths). Trained technicians made spirometry measurements of the FEV1, and the FVC using procedures based on the 1987 American Thoracic Society recommendations.7–9 From these were calculated the FEV1/FVC ratio and the lower limit of the predicted ratio (LLP) for race and age as described elsewhere.5 Subjects were classified using the fixed ratio FEV1/FVC < 0.7 criterion(FR)as air way obstruction present(FR+)orabsent (FR-). They were also classified using the lower limit of normal criterion (LLN) as airway obstruction present (LLN-) or absent (LLN). To assess FR or LLN combined with FEV1, FEV1 was classified as <predicted (FEV1+) or ≥predicted (FEV1).

Measures of outcome and follow-up

The NHANES III linked mortality file contains information based upon the results from a probabilistic match between NHANES III and the NCHS National Death Index records. The NHANES III linked-mortality file provides mortality follow-up data from the date of NHANES III survey participation (1988–1994) through December 31, 2011. Of 33,994 persons with baseline interview data, 13,944 were under age 17, and 26 lacked data for matching. After excluding persons of “other races” and those with missing data for spirometry and other variables shown in Table 1, (e.g. cigarette smoking status) 7472 persons aged 40 and over with complete data remained for this analysis.

Table 1.

Weighted baseline characteristics of participants aged 40 years and over: NHANES III mortality follow-up study 1988–2011.

| Total | No airflow limitation |

FR+/LLN− | FR−/LLN+ | FR+/LLN+ | FR+/low FEV1 |

LLN+/low FEV1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 7472 | 5563 | 659 | 49 | 1201 | 154 | 698 |

| US Population (millions) | 75.2 | 57.0 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 12.0 | 1.3 | 7.1 |

| Age (years), mean | 56 | 55 | 69 | 43 | 60 | 68 | 61 |

| Sex (male)% | 48 | 45 | 60 | 7 | 56 | 61 | 50 |

| FEV1% predicted | 94 | 98 | 90 | 90 | 74 | 70 | 62 |

| FVC % predicted | 97 | 98 | 99 | 102 | 94 | 78 | 84 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 26 |

| Tobacco smoking (%) | |||||||

| Never smoke | 40 | 45 | 35 | 35 | 19 | 38 | 15 |

| Former smoke | 36 | 35 | 46 | 19 | 39 | 34 | 37 |

| Current Smoke | 24 | 20 | 19 | 46 | 42 | 28 | 48 |

| Race (%) | |||||||

| Non Hispanic white | 88 | 87 | 95 | 80 | 90 | 93 | 91 |

| Non Hispanic black | 9 | 10 | 4 | 14 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| Mexican American | 4 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Education <12 years (%) | 26 | 24 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 32 | 37 |

| Conditions (%) | |||||||

| Chronic cough | 11 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 21 | 14 | 26 |

| Chronic Phlegm | 9 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 18 | 16 | 20 |

| Wheeze | 17 | 13 | 15 | 27 | 32 | 28 | 39 |

| Dyspnea | 29 | 25 | 32 | 36 | 42 | 43 | 53 |

| Previous diagnosis of chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema |

9 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 23 | 18 | 30 |

| Self reported health status fair-poor |

18 | 17 | 18 | 15 | 24 | 22 | 31 |

| Any hospitalizations for wheeze in the last 12 months |

3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Any hospitalizations | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

Low FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in the first second < 80%;

FR+, Fixed ratio present;

FR−, Fixed ratio absent;

FVC, Forced vital capacity;

LLN+, Lower limit of normal criterion present;

LLN−, Lower limit of normal criterion absent.

Statistical analysis

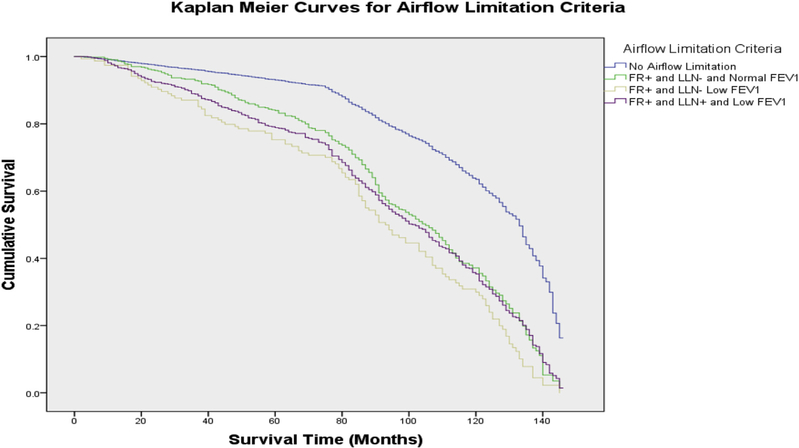

Data from this retrospective follow up study of the NHANES III cohort were analyzed using StataIC Version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) taking into account the sampling weights and complex survey design.4 To assess associations with mortality, survival analyses using log rank test, Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed.10 Survey weights were not adjusted for ineligibility for matching because there were no persons ineligible for matching with mortality data in our analysis sample. Unweighted Kaplan–Meier survival curves shown were computed for six groups based on the presence of obstruction with either the fixed ratio criterion and/ or below the lower limit predicted of normal criterion and a low FEV1 (FEV1 < 80% predicted) or normal FEV1 (weighted Kaplan–Meier analysis not available in Stata). In weighted Cox proportional hazard regression analyses, three models were fit: Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 adjusted for demographic variables (age, sex, race, education years) and Model 3 for demographic variables and other confounders shown in Table 1.

RESULTS

The mean age of all participants was 56 years, 48% were males and the mean percentage predicted FEV1 was 94%. All other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Airway obstruction was defined by 2 criteria: the fixed ratio <0.7 and the lower limit of normal. The prevalence of airflow obstruction was 23% by fixed ratio and 17% by lower limit of normal. Out of the total analytic sample, there were a total of 3554 deaths.

Associations with mortality

Fixed ratio versus lower limit of normal.

As shown in Table 2 weighted Cox proportional hazards regression revealed an increased hazard ratio in persons with FR+/ LLN+ compared with persons with no airflow obstruction (reference group), FR+/LLN- and FR-/LLN+ after adjusting for age (<60 years), sex and ever smoking status (model 1). This remained significant after adjusting for age (<60 years), sex, race, smoking and educational status, and body mass index (BMI) (model 2) and other confounding variables such as self-reported health status, hospitalizations and COPD diagnosis (model 3).

Table 2.

Associations Between Airflow Limitation and mortality: NHANES III 1988–2011.

| Characteristics | Total | No airflow limitation | FR+/LLN− | FR−/LLN + | FR+/LLN + |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 7472 | 5563 | 659 | 49 | 1201 |

| US Population | 75,000,000 | 57,000,000 | 5,500,000 | 530,000 | 12,000,000 |

| Deaths | 3554 | 2251 | 511 | 6 | 786 |

| US Population Death (%) | 37 | 30 | 67 | 57 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.38 (1.20–1.59)* | * | 1.72 (1.55–1.92)* | |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.39 (1.21–1.59) | * | 1.64 (1.49–1.81) | |

| Model 3 | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.74–1.77) | * | 1.22 (0.99–1.50) |

FR+, Fixed ratio criterion present;

FR−, Fixed ratio criterion absent;

LLN+, Lower limit of normal criterion present;

LLN−, Lower limit of normal criterion absent.

not shown due to <10 deaths.

Thus, persons with both abnormal fixed ratio and lower limit of predicted had the poorest prognosis.

Effect of low FEV1.

To assess the effect of FEV1 on mortality, the sample was further categorized into 6 groups by low vs normal FEV1. Unweighted Kaplan–Meier survival estimates showed survival declining most for those with low FEV1 compared to those with no impairment (Figure 1). Survival was intermediate in other groups. An unweighted log-rank test was significant (p = 0.000). Curves for the two groups with few deaths are not shown.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier survival curves in persons aged 40 years and over: NHANES III 1988–2011.

Curves indicate proportion surviving (y axis) at specified months (x axis) after baseline evaluation for 7472 adults. Low FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in the first second < 80%; FR+ = Fixed ratio present; LLN+ = Lower limit of normal criterion present; LLN- = Lower limit of normal criterion absent.

Table 3 shows sample counts for all six groups and regression results for 4 groups with sufficient number of deaths. Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression revealed an increased hazard ratio in persons with low FEV1. Persons with normal FEV1 and airway obstruction by FR, had significantly elevated risk in model 1 which remained significant in models 2 and 3. Persons with low FEV1 also had increased risk.

Table 3.

Associations between airflow limitation criteria alone and further refined by FEV1 and mortality (N=7,472): NHANES III 1998–2011.

| FR− and LLN− and Normal FEV1a |

FR+ and LLN− and Normal FEV1 |

FR−, LLN + and Normal FEV1 |

FR+ and LLNL Low FEV1b |

FR−, LLN+ and Lowb FEV1* |

FR+ and LLN + and Low FEV1b,c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5056 | 505 | 41 | 154 | 8 | 690 |

| Model 1 | 1.000 | 1.279 (1.144, 1.430)* | - | 1.762 (1.468, 2.115)* | - | 1.798 (1.624, 1.989) |

| Model 2 | 1.000 | 1.180 (1.054, 1.321) | - | 1.717 (1.430, 2.062) | - | 1.647 (1.485, 1.827) |

| Model 3d | 1.000 | 1.189 (1.062, 1.331) | - | 1.672 (1.392, 2.009) | - | 1.576 (1.415, 1.755) |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s;

FR+, Fixed ratio present;

FR−, Fixed ratio absent;

LLN+, Lower limit of normal criterion present;

LLN−, Lower limit of normal criterion absent;

MRC, Medical Research Council;

SF-12, Short Form 12-item health survey.

Notes: Proportional hazard regression analysis, except as otherwise noted. All models adjusted for age-group (<60 years), sex, and ever smoking. Data are presented as adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) or parameter estimate (P value) from regression analysis.

not show due to <10 deaths.

Reference group (FR-/LLN-).4

FEV1 <80% of predicted.4

Collectively, these 2 criteria constitute Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 2 or higher disease.11

Ordinal logistic regression used to confirm proportional hazards analysis.4

DISCUSSION

At present Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines include the use of FEV1/ FVC < 0.7 (fixed ratio) together with FEV1 < 80% predicted to establish the diagnosis and stage of COPD.11 Others who feel the fixed ratio is too sensitive with insufficient specificity among older persons suggest the use of the FEV1/FVC ratio below the lower limit of predicted. This is one of the first studies comparing the prognostic power as it relates to mortality of the fixed ratio versus the ratio below the lower limit of predicted in addition to the use of FEV1. We conducted two analyses in this study. The first analysis compared the fixed ratio versus the lower limit of predicted in predicting mortality, and the second examined the effect of adding the FEV1 to the fixed ratio and/or the lower limit of normal to increase the prognostic power.

This study suggests that abnormal fixed ratio or lower limit of normal increases the likelihood of mortality. Both abnormal further increases risk compared to either alone. However, there was a low number of deaths in the group with obstruction defined by lower limit of predicted with normal FR; therefore, we could not compare it directly with those with obstruction defined by fixed ratio alone. Furthermore, the categorization by FEV1 added predictive power to both the fixed ratio and the lower limit of normal and to either of them alone for prognosis. Persons with only an abnormal fixed ratio but normal LLN and FEV1, did not have significantly increased mortality.

Previous studies

Our results complement those of the recently published CanCOLD study12 which was a cross-sectional study examining the clinical relevance of both criteria by comparing their associations with different patient reported outcomes like exacerbations, health status and symptoms. The authors of this study concluded that a diagnosis of COPD established by either criteria or both in addition to a low FEV1 was strongly associated with the above clinical outcomes. They further recommended a longitudinal study to evaluate clinical outcomes such as this present study. Consistent with the CanCOLD study, our study showed a poorer survival in those with low FEV1. Our study differed from the CanCOLD report in various ways including the fact that this was a follow-up study with mortality-linked data in a US-based cohort. Also, this study examined only mortality outcome, whereas the Can COLD study considered various reported patient outcomes like exacerbations, health status and symptoms. Thirdly, our study used the pre-bronchodilator spirometry measurements, whereas the CanCOLD study utilized postbronchodilator spirometry measurements.

The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study was an international effort using standardized methods to examine the prevalence and economic burden of COPD.13 That cross-sectional analysis compared the use of three spirometry criteria for the diagnosis of COPD in over 10,000 non-institutionalized people. Unlike our study and the CanCOLD study, BOLD compared the use of both criteria but in addition they examined the clinical relevance of FEV1/FEV6 ratio. The results confirmed the lack of specificity associated with the use of the fixed ratio criterion alone.

Others studied the clinical relevance of spirometric criteria using data from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) cohort comprising of over 5000 men and women aged 65 years and older.14 Similar to our study CHS lacked post-bronchodilator measurements. Outcomes were death and hospitalization. There were 1621 deaths and 934 subjects had at least one hospitalization during the followup period. Compared to normal, subjects with COPD based on fixed ratio criteria only (but with normal LLN and FEV1) had a significantly increased risk of death with an adjusted hazard ratio = 1.2 (95% CI 1.13e1.40), similar to NHANES result (Table 3), whereas those with FEV1/FVC < 0.7 and LLN, and FEV1 <50% had a significantly greater increased risk of death with an adjusted hazard ratio = 3.0 (95% CI 2.4e3.7). Further cohort studies to replicate their findings were suggested.

Among several previous studies using the NHANES III data, one survival analysis looked at 6261 persons aged 50 years and over.15 Compared with those with no respiratory symptoms and normal spirometry, persons with GOLD (2007) stage 2 had an adjusted hazard ratio = 1.4 and those with GOLD stage 3 or 4 had an adjusted hazard ratio = 2.6. Another NHANES III survival analysis of 6184 persons aged 40 years or over found among those with airway obstruction, those with overt cardiovascular disease were no more likely to die than those without cardiovascular disease compared to “normal” subjects.16 A recent analysis of persons aged 20 years and over in NHANES III found those with FEV1/FVC <0.70 but with no physician diagnosis of COPD had an adjusted hazard ratio = 1.25 (1.10e1.42) compared with those with no obstruction.17

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths including the fact that the NHANES study utilized a complex, multistage sampling method to reduce possible sampling bias and produce estimates for the US population. The analytic sample represents over 75 million of Americans age 40 years and over. All methods were standardized and subject to quality control. Spirometry was obtained according to the ATS guidelines.7 The questionnaires administered were adapted from instruments validated in other studies. NHANES III linked-mortality files have been successfully used in many previous survival analyses. To minimize confounding bias, several variables known to impact outcomes in patients with COPD were adjusted for in multivariate analysis. Sample size was adequate to ensure adequate precision of most of the hazards ratios. Results can be generalized to over 75 million American adults.

Ideally, diagnosis of COPD requires confirmation of an airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible postbronchodilator via spirometry in a patient who has a history of a potentially causative exposure.7 Airflow limitation that is not fully reversible is defined by a low postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio. However, in this study post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC was not available, as bronchodilators were not given in NHANES III. The BOLD study reported a lower prevalence of COPD in post-bronchodilator measurements compared with prebronchodilator measurements. This might cause overdiagnosis of airflow obstruction using the FR, but should have little effect of LLN, since NHANES III norms derive from pre-bronchodilator data. Confounding by variables not controlled for such as air pollution and adherence to medications cannot be excluded. Due to the relatively small number of persons reliable estimates were lacking for two categories. These findings thus need to be replicated in a larger cohort with post-bronchodilator spirometry. Results may not be generalizable to persons who were under 40, unable to perform spirometry, or races other than non-Hispanic whites, blacks and Mexican Americans.

Implications

The addition of FEV1 < 80% of predicted increased the prognostic power for mortality of the fixed FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 and/or FEV1/FVC below the lower limit of predicted criteria for airway obstruction in a US national cohort. Future studies should confirm these findings using postbronchodilator spirometry measurements. The predictive power of FEV1/FEV6 could also be assessed in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Abbreviations:

- BOLD

Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FR+

Fixed-ratio criterion present

- FR-

Fixed-ratio criterion absent

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in the first second

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- GOLD

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease

- LLN+

Lower limit of normal criterion

- LLN-

Lower limit of normal criterion present

- LLN

Lower limit of normal criterion absent

- LLP

Lower limit of the predicted ratio

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES III

Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors (YO, JN, OL, KD, RG and AM) have any financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Yewande E. Odeyemi, Department of Internal Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA; Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

O’Dene Lewis, Department of Internal Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA; Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

Julius Ngwa, Department of Internal Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Kristen Dodd, Division of Geriatrics, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Richard F. Gillum, Department of Internal Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA; Division of Geriatrics, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Alem Mehari, Department of Internal Medicine, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA; Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. (2013. February 15). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 187(4), 347–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faner R, Rojas M, Macnee W, & Agustí A (2012. August 15). Abnormal lung aging in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 186(4), 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, & Liu X (2011. June). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS Data Brief, 63, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHANES - Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/survey_methods.htm.

- 5.Hankinson JL, & Bang KM (1991. March). Acceptability and reproducibility criteria of the American Thoracic Society as observed in a sample of the general population. Am Rev Respir Dis, 143(3), 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannino DM, Ford ES, & Redd SC (2003. December). Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination. J Intern Med, 254(6), 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PFT2.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2016 Sep 19]. Available from: www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/pfet/PFT2.pdf.

- 8.Barnes TA, & Fromer L (2011). Spirometry use: detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Clin Interv Aging, 6, 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, & Fedan KB (1999. January). Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 159(1), 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ststs.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2016 Jan 6]. Available from: www.stata.com/manuals13/ststs.pdf.

- 11.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 3]. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/.

- 12.van Dijk W, Tan W, Li P, et al. (2015. January). Clinical relevance of fixed ratio vs lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC in COPD: patient-reported outcomes from the CanCOLD cohort. Ann Fam Med, 13(1), 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer WM, .Gíslason P.., .Burney P.., et al. (2009. September). Comparison of spirometry criteria for the diagnosis of COPD: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J, 34(3), 588–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mannino DM, Buist AS, & Vollmer WM (2007. March). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the older adult: what defines abnormal lung function? Thorax, 62(3), 237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Kush SJ, Mannino DM, & Strauss DJ (2009). Life expectancy and years of life lost in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: findings from the NHANES III Follow-up Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 4, 137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mannino DM, Davis KJ, & Disantostefano RL (2013. October). Chronic respiratory disease, comorbid cardiovascular disease and mortality in a representative adult US cohort. Respirology, 18(7), 1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez CH, Mannino DM, Jaimes FA, et al. (2015. December). Undiagnosed obstructive lung disease in the United States. Associated factors and long-term mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc, 12(12), 1788–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]