Abstract

Clinical guidelines discourage prescribing opioids for chronic pain but give minimal advice about how to discuss opioid tapering with patients. We conducted focus groups and interviews involving 21 adults with chronic back or neck pain in different stages of opioid tapering. Transcripts were qualitatively analyzed to characterize patients’ tapering experiences, build a conceptual model of these experiences, and identify strategies for promoting productive discussions of opioid tapering. Analyses revealed 3 major themes. First, due to dynamic changes in patients’ social relationships, emotional state, and health status, patients’ pain and perceived need for opioids fluctuate daily; this may conflict with recommendations to taper by a certain amount each month. Second, tapering requires substantial patient effort across multiple domains of patients’ everyday lives; patients discuss this effort superficially, if at all, with clinicians. Third, patients use a variety of strategies to manage the tapering process (e.g., keeping an opioid “stash,” timing opioid consumption based on planned activities). Recommendations for promoting productive tapering discussions include understanding the social and emotional dynamics likely to impact patients’ tapering, addressing patient fears, focusing on patients’ best interests, providing anticipatory guidance about tapering, and developing an individualized tapering plan that can be adjusted based on patient response.

Keywords: chronic pain, opioid analgesics, patient-physician relations, opioid tapering, theoretical models, qualitative research, primary care

PERSPECTIVE

This study used interview and focus group data to characterize patients’ experiences with opioid tapering and identify communication strategies that are likely to foster productive, patient-centered discussions of opioid tapering. Findings will inform further research on tapering and help primary care clinicians to address this important, often challenging topic.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain is among the most common complaints in primary care,15 yet patients and clinicians consistently report that negotiating treatment plans for chronic pain is often mutually frustrating and unproductive, especially when treatment involves opioid analgesics.11, 24, 30 Substantial increases in the use of opioids to treat chronic pain during the late 1990s and early 2000s16 and the subsequent rise in rates of opioid-related overdose27, 28 have prompted dramatic shifts in clinical practice away from opioid use. New clinical guidelines, such as those published by the CDC and Department of Veterans Affairs, discourage use of long-term opioids for chronic pain and recommend tapering patients either off opioids or to daily doses below 90 mg morphine equivalents.9, 10 This shift in clinical practice and attendant system-level efforts to reduce opioid prescribing14 may make discussions about opioid tapering even more common.

Clinical guidelines provide general recommendations about opioid tapering rates (e.g., 10–20% dose reduction every 2–4 weeks2) but offer few concrete suggestions for how to discuss tapering with patients; CDC guidelines merely advise clinicians to “work with patients to taper opioids.” There is thus a need to identify specific strategies for negotiating opioid tapering plans that facilitate patient-centered care and reduce mutual frustration. Such strategies are more likely to be patient-centered if they are grounded in an understanding of how patients experience opioid tapering. Frank et al. have examined patient-reported barriers and facilitators to opioid tapering,12 but to date no study has investigated patients’ tapering experiences.

This study sought to gain insight into patient experiences with opioid tapering by conducting focus groups and individual interviews with patients suffering from chronic neck and/or back pain. We focused on axial musculoskeletal pain because it is the most common homogeneous pain condition for which long-term opioids are typically prescribed3 and is a leading cause of work-related disability.4 Data were inductively analyzed to develop a conceptual model of patients’ tapering experiences. Based on this model, we recommend strategies clinicians can use when discussing opioid tapering with patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and recruitment

Participants were adult patients at 13 different primary care clinics within the University of California, Davis Health System located in the greater Sacramento area. Eligible patients were 35 – 85 years old with chronic neck or back pain and were either taking long-term opioids (defined as ≥1 dose per day for ≥3 months) or had taken long-term opioids (≥1 dose per day for ≥3 months) and had tapered down or off within the past year. We recruited patients ≥35 years old because our prior research found very few patients younger than 35 taking long-term opioids for chronic back or neck pain.18 Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, active cancer treatment, hospice or palliative care, and patients prescribed opioids by specialists rather than primary care clinicians. This study is part of a larger project approved by the University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board to collect and share patient stories about opioid tapering. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

An electronic health record screening algorithm was used to identify potentially eligible patients. Study personnel gave primary care clinicians lists of their patients identified by the algorithm and asked clinicians to identify patients who were good candidates for opioid tapering, were in the process of tapering, or had recently finished tapering. We included patients for whom tapering had been recommended but not started because discussions about starting tapering are often fraught and highly salient for patients and clinicians.20 Study personnel independently contacted these patients, assessed eligibility, and invited interested patients to participate.

Data collection

Before focus groups, patients completed questionnaires that asked about demographic information (see Table 1), pain severity (measured by the 3-item PEG21), pain duration, patients’ report of their tapering status (primary care clinician has recommended tapering, patient is in the process of tapering, patient has completed tapering within the past year), and selected items about opioid-related behaviors and attitudes from the Current Opioid Misuse Measure5 and the Prescribed Opioids Difficulty Scale1 (See online Table). The study focus was patients’ experiences and understanding of tapering; therefore, we did not impose dose-specific thresholds or definitions of tapering when recruiting patients. Nor did we abstract data from patients’ medical records (e.g., co-morbid diagnoses or prescribed opioid dose). During focus groups, patients told their personal stories about pain management, medication management, and opioid tapering. An open-ended focus group guide was used to organize the discussion, with topics derived from the Health Belief Model.17 Major topics included perceived barriers and benefits to tapering, strategies for communicating with clinicians, strategies for managing pain and opioids, and sources of support. Focus group discussions allowed patients to react to and interact with other patients, producing richer data than individual interviews. One investigator conducted all focus groups, while another investigator took notes. Patients were recruited based on opioid use during the previous year; however, the interviewer did not restrict discussion to experiences during the previous year, because patients routinely described their tapering experience in the context of their overall pain experience.

Table 1.

Characteristics of focus group participants (n = 21)

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 58.2 (8.3) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 10 (48%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African-American | 2 (10%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (5%) |

| Caucasian | 16 (76%) |

| Native American | 1 (5%) |

| American/Mexican/Indian | 1 (5%) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 2 (10%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 3 (14%) |

| Some college | 12 (57%) |

| Bachelor degree | 4 (19%) |

| Master’s degree | 2 (10%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Full time | 4 (19%) |

| Out of work | 1 (5%) |

| Not able to work | 12 (57%) |

| Retired | 4 (19%) |

| Annual household income, n (%) | |

| < $40,000 | 5 (24%) |

| $40,000 - $80,000 | 10 (48%) |

| > $80,000 | 6 (29%) |

| Average pain1, mean (SD) | 5.7 (2.4) |

| Pain intensity, mean (SD) | 6.0 (1.9) |

| Pain has interfered with enjoyment of life, mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.0) |

| Pain has interfered with general activity, mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.9) |

| Pain location, n (%) | |

| Back pain only | 3 (14%) |

| Neck pain only | 3 (14%) |

| Both back and neck pain | 15 (71%) |

| Status of opioid tapering, n (%) | |

| Already tapered | 14 (67%) |

| Currently tapering | 4 (19%) |

| Recommended to taper | 3 (14%) |

| Which one choice best describes how long you have been suffering from chronic pain?, n (%) | |

| 2 years < 5 years | 3 (14%) |

| 5 years < 10 years | 6 (29%) |

| 10 years or more | 12 (57%) |

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Range 0 to 10, with higher numbers reflecting more severe pain during the past week. Pain was measured using the 3-item PEG scale.20

The most compelling storytellers (i.e., patients who investigators judged were best at engaging and opening other patients to the possibility of tapering) were identified based on group dynamics, audio recordings, and transcripts. These patients were invited to return for individual 30-minute interviews. Individualized interview guides were used to prompt interviewees to recount and elaborate on the stories they told during their focus group.19 Interviewees were contacted the day before their interview and reminded of the study purpose and aspects of their stories shared during the focus group. Interviewees were not coached on what to say or how to answer questions. Both focus groups and interviews were audio recorded and transcribed.

Data analysis and model development

Four investigators iteratively reviewed all interview transcripts to identify the kinds of stories patients told about tapering and themes in patient accounts of their tapering experiences. Investigators met every 2 weeks for 6 months to discuss and compare their interpretations of findings and to resolve differences among investigators.25

Investigators summarized key themes and concepts that emerged from the data and used them to develop a conceptual model of patients’ tapering experiences. During model construction, investigators paid attention to both supporting and potentially contradictory evidence in the data. Based on this analysis, we developed recommendations for improving patient-clinician communication about opioid tapering, with the goal of providing guidance for clinicians seeking to encourage patients to attempt opioid tapering while also maintaining therapeutic patient-clinician relationships.

RESULTS

Participants

Of the 89 patients contacted and screened, 70 (79%) were eligible, and 62 (89% of eligible patients) agreed to participate, though most of these patients did not participate due to scheduling difficulties. Twenty-one patients participated in 4 focus groups between November 2016 and March 2017. Table 1 shows enrolled patients’ characteristics. Patients had a mean age of 58, were 48% male, and 76% white. Median household income was $60,001 – $80,000; 57% reported being disabled or unable to work. Sixty-seven percent of patients (n=14) had recently completed an opioid taper (with 4 of these patients no longer taking any opioids), 19% were in the process of tapering, and 14% had discussed tapering but had not made any changes. Patients reported a mean pain severity of 5.7; all had pain for >2 years. Most patients (71%) endorsed both back and neck pain. Patients reported a range of attitudes about opioid effectiveness and potential harms; the online Table shows complete results for these items. Based on group dynamics and data review, 10 patients were invited for individual interviews. Two declined and one was unable to participate due to scheduling conflicts, leaving interviews with 7 patients. Of these 7, 4 had completed tapering, 2 were currently tapering, and 1 had been recommended to taper.

Conceptual model

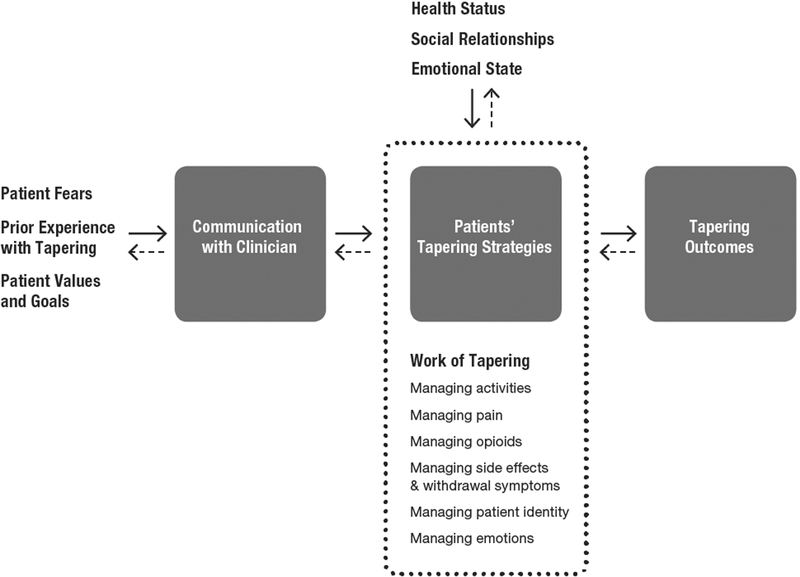

Figure 1 shows our final conceptual model. The model reflects three crosscutting themes. First, patients’ social relationships, emotional state, and health status all affect patients’ tapering strategies, and can either facilitate or impede tapering. Due to the dynamic nature of these factors, patients’ pain and perceived need for opioids fluctuate daily, a reality that may be at odds with recommendations to taper opioids by a fixed percentage every 2–4 weeks. Second, tapering requires substantial effort, or work, across multiple domains of patients’ everyday lives; however, patients discuss the work of tapering superficially, if at all, with clinicians. Third, patients use a variety of strategies to manage the tapering process. These strategies can be patient-initiated, clinician-recommended, or formulated jointly by patient and clinician. The two-way arrows indicate that tapering is a dynamic process, and that patients adjust their tapering strategies based on changes in their health status, social relationships, and emotional state. Individual model components are discussed in detail below.

Figure 1. Model of patients’ experience with opioid tapering.

Patients’ fears, prior experience with tapering, and values and goals influence patient communication with clinicians about tapering, which in turn influences the tapering strategies patients employ. Dynamic changes in patients’ social relationships, emotional state, and health status affect their tapering experience, and can either impede or facilitate tapering. The dotted line indicates that the work or effort patients must expend to taper successfully involves managing a wide range of domains that impact and are impacted by patient’s social relationships, emotional state, and health status. Patients’ tapering strategies influence tapering outcomes, which include attitudes about tapering and opioid consumption. The two-way arrows indicate that tapering is a dynamic, non-linear process for patients.

Prior experience with tapering

Patients rarely approached opioid tapering as a blank slate. Many recounted prior experiences with tapering, and most had ideas about what tapering meant or might entail. Several patients had tapered down or off opioids more than once. Patients had varying ideas about what tapering meant; these ideas influenced attitudes about tapering and discussions with clinicians. Common synonyms for tapering were “cutting back,” “reducing my medications,” “weaning off,” “going cold turkey,” “detoxing,” and “adjust[ing] down to nothing.” Patients who understood tapering to mean a gradual or partial reduction in opioid medications were generally more receptive to tapering than those who understood it to mean stopping “cold turkey” or stopping opioids completely. Patients who used the terms “taper” and “detox” interchangeably tended to associate tapering with withdrawal symptoms.

Patient values and goals

Patients’ values and goals influenced their attitudes towards opioid tapering. Some patients were willing to attempt tapering because they wanted to take fewer medications. Several patients wanted to taper because they felt that their lives revolved around opioids:

My life before I started the tapering process, I was kind of stuck in a box. I was on opiate medication I have to take regularly, I was more like a slave to it, and I basically there part of me said there’s gotta be another way.

I’ve had it where I’ve gone to work before, and even though I lived an hour away, and I realized I didn’t have one to take a two o’clock dosage, I said, “I gotta go home.” I wouldn’t tell anybody why I was going home, but I would go home just to get that. So, it pretty much, it does run your life.

Other patients cited the goal of better health as a motivation for tapering. One patient noted, “I think your body is just not meant to try to process that medication over a long period of time.” Most patients mentioned some opioid-related side effects, but side effects alone were rarely sufficient to motivate patients to attempt tapering. A few patients described making decisions about tapering based on risks versus benefits of long-term opioid use with language similar to the CDC guidelines: “If [opioids] work for you, what are the negatives? Balance it out. Like I said, if they even got rid of half the pain in my knees, I’d keep taking them.” “I’m kind of an advocate for, if you need them, take them. … If you need them for quality of life, do it.”

Patient fears

Fear emerged as a uniquely powerful emotion affecting both patients’ willingness to taper and their overall tapering experience. Most patient fears involved the possibility of worse pain and withdrawal due to decreased opioids. One patient was so afraid of withdrawal that she would only attempt tapering in an inpatient facility. For most patients, the prospect of tapering evoked fears involving a mix of pain, withdrawal, and loss of function: “I have that fear that if I stop, things are going to go to hell. I don’t want to be in that situation again.” One patient described inchoate fear after a clinician refused to refill her oxycodone: “I just remember sitting in the doctor’s office and tears were just pouring down my face because I thought, ‘What the hell do I do now? How do I live with this?’”

Fears of addiction and overdose were less prominent than fears of pain and withdrawal. As one patient noted, “I have a lot of doctors say, ‘Aren’t you worried about being addicted to the pain medication?’ My God, I’ve been on it for 25 years. I am obviously addicted to it so that is not a concern.” A few patents cited specific incidents such as the one below that precipitated their desire to taper:

I think the defining moment for me was, I was standing holding one of the babies and I fell asleep. My family had had it. They had had it so I wasn’t allowed to see the kids, none of my grandkids, until I decided what I was going to do. …I didn’t think that I had a problem. When I went to my first consultation with the rehab lady, I was like, this is not a problem until I detoxed. Once I detoxed, it was like, holy crap. This is a problem.

Social relationships, emotional state, and health status

Patients’ social relationships and emotional state frequently influenced their experiences with opioid tapering. With the exception of stories about patient-clinician interactions, most patient stories about tapering emphasized social relationships and emotional dynamics. Two of the most common dynamics impacting tapering were patients’ ability to fulfill their roles and responsibilities related to their work and family. For example, one patient deferred tapering until after retirement because he needed opioids in order to work.

The excerpts below show examples of the interplay between patients’ family responsibilities and opioid tapering:

My mother-in-law came to live with us about three months ago. She needs care, so guess who’s having to take care of her when I get home? That means I’ve got to take less medication to be able to function when I get home.

I still try to be productive around the house, and part being a taxi for the family, you’re driving people and stuff like that, so coherence is my responsibility… Sometimes I end up breaking one of my tablets in half—not much effect in it but you know, I try to do a little mental stuff.

Changes in patients’ health status also influenced their tapering experiences, often through new medical problems and repeat injuries. One patient reported starting, escalating, and then tapering off opioids 3 separate times; the last 2 episodes were due to injuries during car accidents.

The work of tapering

Patients repeatedly emphasized that tapering requires planning and sustained effort: “It’s a process, it’s not something that you do one day and it’s gone the next.” “Understand that you are going to go through a lot of different changes [during tapering]. It’s normal.” Patients experienced tapering as dynamic because their pain and perceived need for opioids varied from day to day and because their pain was frequently affected (either positively or negatively) by changes in their social relationships and emotional state. Tapering requires patients to adjust and recalibrate in response to these changes. When asked how she would advise others about tapering, one patient said, “it’s just that pain changes. It doesn’t stay the same. Like everything, there’s just constant change. It may take a while for it to change. It may get worse, it may get better.” The two-way arrows in the model reflect the dynamic nature of the tapering process.

The effort needed to taper spans several interconnected domains: managing activities, managing opioids, managing pain, managing side effects and withdrawal symptoms, managing patient identity, and managing emotions. Most patients already worked hard to manage pain and opioids prior to tapering; tapering required patients to try new and different strategies.

The most salient effort during tapering was figuring out how to manage activities necessary to get through the day (e.g., working, running errands, helping family). Patients continually adjusted opioid use based on their planned activities.

If we need to go to the store, then before you go, you have to take your pain medication, because otherwise, you’re going to just die when you get home. … You have to plan around for going to the store. Even for going to the doctor appointment… you can’t take too much, because I don’t want to take that and then drive.

Tapering often required patients to expend more effort adjusting their habits and opioid consumption to maintain functionality. The following excerpts illustrate how tapering prompted some patients to curtail or re-think activities, while others adopted new strategies (e.g., staying physically and socially active) to manage pain and get through the day.

So I’m actually having to learn to say I can’t do that. I thought I could do it, but I can’t. So I’m gonna have to re-figure out how to do certain things. Instead of running, now I walk with the kids. It’s just I’ve had to re-learn how to do things and to accept that some things I’m not gonna be able to do.…I’m a huge Disneyland fan. …. And I realized I can’t ride some of the rides I always did.

I’ll do projects around the house and it keeps me going and it helps keep … and a lot of times, the kids, I’m working on the kids’ cars for them than myself ‘cause it’s just keeping me going. Whatever it is that helps you keep moving. Some people can’t move that much and that’s okay, but it’s the, be active and be engaged with other people as best as you can because it will help you.

Nearly all patients noted that managing opioids became more difficult as tapering progressed. In addition to timing opioid consumption around daily activities and contacting clinics for refills, patients expended more energy monitoring their day-to-day opioid supply. Several patients compared managing opioids to a second or “secret” job.

Patients also worked to avoid withdrawal: “right now, if I’m an hour late on my dose, I get sick to my stomach.” Patients had to continually exert self-control to balance their immediate desire for pain relief against their fear of worse pain or withdrawal if they ran out of opioids in the future. The two patients quoted below made different decisions about these tradeoffs:

The reality of tapering off medication, for me, has been that if I’m careful, and I really follow the plan of taking a pill every six hours, or every eight hours, I’m going to be okay. … I may be somewhat physically uncomfortable, but I’m not in screaming pain. I’m in screaming pain when I’ve taken too much medication one day and don’t have enough for the next day.

I can either feel like 80% my normal self for the whole month, or I can feel like I used to feel good for three weeks, and then the last week, I don’t take any because it’s all gone. Then you get the headaches and that kind of stuff. It’s worth it to me to do that, to be able to live the first three weeks.

Even patients who realized that their fear of uncontrolled pain was unfounded admitted they had to tolerate greater discomfort in order to “get by” with fewer opioids. Patients who tapered off opioids noted that withdrawal symptoms lasted weeks to months; one patient still experienced withdrawal symptoms a year after stopping oxycodone.

Managing emotions during tapering mostly entailed managing the fears described above. One patient noted that having fewer pills heightened her fears of uncontrollable pain, which in turn required her to expend more energy controlling these fears: “when I had 30 a month, I didn’t have to think about it, because I knew I had enough. Now that I have 20 … I have the side effect of obsessing about how many I have.” Failure to control ones’ fears often made pain worse: “I would start to feel pain coming on and it would be like my mind would say, ‘Oh my God, you’re going to…’ It’s like this fear of the worst pain you ever had and it literally almost makes it manifest.”

Many patients also expressed struggles with their identity, including doubts about self-worth, worry about acceptance by others, and a desire to return to how they were before they started opioids. For several patients, dissatisfaction with being a “pain patient” motivated their desire to taper; one patient tapered because “I want to reclaim certain things in my life that were enjoyable, and I feel pain medication has altered.” For others, tapering involved accepting pain-related limitations. For many patients, successful tapering required consciously reconstructing their identity; this patient found ways to feel pride despite his frustration at not providing for his family:

I gotta lift myself up and I gotta push on. Sometimes I’ll do it still under some pain, some stress, but I feel good on doing whatever I’m doing for the family or whatever it is that I need to keep pushing on and doing it ‘cause once I eventually accomplish it, I feel great that I didn’t let nothing hold me down and stop me from achieving things that I still—I can—achieve to do.

Some patients associated tapering off opioids with positive changes in their identity, while others had little hope for the future due to their persistent, debilitating pain.

Communication with clinicians

Clinicians play a key role in patients’ tapering experience because clinicians are the only legal source of opioids and the primary source of medical treatment for pain. Patients reported that discussions with clinicians tended to focus on opioid dosing and medically prescribed pain treatments; discussions of patients’ everyday experiences with tapering, their social relationships, and their emotional state were rare.

Clinicians’ involvement in and initiation of tapering varied greatly. Some clinicians were minimally involved in tapering decisions (e.g., when patients decided, on their own, to quit “cold turkey”), though nearly all were supportive of patients who wanted to taper. Discussions about tapering were sometimes initiated by patients, sometimes initiated by clinicians, and sometimes mutually agreed upon. Patients whose clinicians unilaterally tapered or stopped prescribing opioids expressed a profound sense of loss and betrayal: “This has been my doctor for almost 20 years and he treated me like a stranger, like nothing.” Another patient used similar language:

I felt like, where did you go? When I attempted suicide, he checked on me daily and he made me sign a contract not to hurt myself and then here he is years later. Where did that loving, caring doctor go? I’m so loyal to you… I always looked to him for comfort and humor and caring and that just wasn’t there. It was just this stranger sitting there.

Patients reported a wide range of experiences with clinicians once tapering started. Patients who described positive relationships with their clinicians, and who identified clinicians as a source of support during tapering, gave similar answers about effective patient-clinician communication around tapering. First, they expressed the importance of mutual honesty—clinicians being honest with patients, and patients being honest with clinicians and with themselves. This patient described mutual honesty as a pre-requisite for successful opioid tapering.

If you’re struggling with your doctor, or struggling with the relationship with your doctor, I would first begin asking yourself, am I being completely honest with my doctor, and if I’m not, why not. That’s a big question, because I found myself at times when I wasn’t entirely honest with my doctor, and it was at the times when I pretty much wanted to medicate myself the way I wanted to medicate myself.

Second, these patients described clinicians who took the time to learn about their needs, build mutual trust, and devise individualized tapering plans. Several patients noted that simple, open-ended questions such as, “How are the pain medicines working for you?” and, “What problems are you having?” facilitated productive information exchange and signaled that clinicians were not using a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Finally, patients who reported positive experiences received anticipatory guidance about tapering and described clinicians willing to adjust tapering plans based on patients’ experience or in response to changes in patients’ emotional state or health status: “[my doctor] is very supportive. If I was in more pain, I feel like I could go back to her and say, ‘I need more.’”

In contrast, patients reporting negative interactions with clinicians felt clinicians were not entirely honest about their reasons for tapering (e.g., clinicians were motivated by institutional anti-opioid pressures rather than patients’ best interests), did not listen to patients or individualize tapering plans, or were inflexible once tapering started. Several patients reported experiences with clinicians who they perceived as focused on tapering opioids rather than treating pain:

When you say you want to go down and get off of it, I’m making an initiative. He’s not asking me to, and yet when I say, “Well, maybe I shouldn’t have gone all the way off. At least maybe I should have something as a backup for when it’s really, really bad.” He comes back to me and says, “Uh, no, no. Sorry, we don’t go backwards.”

Patients explicitly discussed the power differential between patients and clinicians—only clinicians can prescribe (or refuse to prescribe) opioids—when they described negotiating about opioid dosing or the rate of tapering. Patients were often reluctant to challenge clinicians for fear of losing access to other medical services or of being labeled a “drug seeker.”

For several patients, tapering discussions were precipitated by clinician retirement. Other patients noted they had trouble finding primary care clinicians willing to prescribe opioids when they needed to change clinicians. As shown in the excerpts below, changing clinicians is one of the few options patients have for resolving persistent disagreements about tapering and opioids.

I decided that I needed to start tapering. And…brought it up with my doctor that I currently have. The one I have right before her. I ended it, because she told me that I would never be off of them, and she doesn’t ever see me going off, and I just couldn’t accept that. …So, I went and changed doctors.

My back got worse, the pain was getting worse, and [my doctor] hadn’t really sent me for more diagnostics, and I hadn’t been referred to the pain clinic yet. I just sent him an email…and I said, “Can I have another prescription for opioids?” He said, “Instead of just throwing medicine … at these problems, come in and we’ll talk about it.” …I was like, “I’ve talked to you about these problems. I don’t want to come in and talk to you about them again. They’re prescriptions I’ve had. Why do I have to?” That’s actually what made me seek another doctor.

A few patients considered seeking alternative opioid sources during tapering when their pain or withdrawal was severe. One patient suffering from withdrawal during tapering accepted unknowingly counterfeit hydrocodone pills from an acquaintance, resulting in hospitalization for overdose. Another patient admitted that when his supply of opioids gets low, he imagines either buying heroin or injuring himself to obtain additional opioids.

Tapering strategies

Patients described a wide variety of strategies to navigate opioid tapering. Table 2 lists the strategies discussed in our data. These strategies fall into three general categories: patient-initiated, clinician-initiated, and mutually agreed upon. Most patients did not draw sharp distinctions between strategies for managing pain and opioids generally and strategies specific to tapering. Some patient-initiated strategies indicated possible substance use disorder or “aberrant” opioid-related behaviors; this study focused on patient experience and did not evaluate strategies’ appropriateness.

Table 2.

Patient strategies used to manage opioid tapering*

| Primarily patient-initiated |

| Adjust or limit activities based on opioid supply |

| Adjust timing of opioid consumption based on planned activities |

| Alcohol |

| Avoid family and friends when “cranky” due to withdrawal |

| Break pills in half to make supply last longer |

| Caffeine (to reduce withdrawal symptoms) |

| Cannabis |

| Chiropractic |

| Having a family member / friend control opioid supply |

| Maintain an opioid “stash” for emergencies |

| Maintain social and family interaction |

| Make a schedule of planned daily activities and medication consumption each morning |

| Massage / massage therapy |

| Meditation |

| Obtain opioids from a friend |

| Pursuing activities/hobbies to keep the mind off pain (e.g., video games, bird watching) |

| Physical exercise / staying physically active |

| Reiki therapy |

| Research tapering and tapering strategies on the internet |

| Seek advice and support from family and friends who have tapered |

| Stay cognizant of your psychological health |

| Stop opioids “cold turkey” and “tough out” withdrawal symptoms |

| Support based on religious faith |

| Twelve-step programs |

| Yoga |

| Primarily clinician-initiated |

| Non-opioid analgesics (gabapentinoids, tricyclics, acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, etc) |

| Medication to treat withdrawal symptoms (e.g., clonidine) |

| Physical therapy, including pool therapy |

| Refer to pain clinic for procedures (e.g., nerve ablation, epidural steroid injection) |

| Refer to other specialists (e.g., neurology, psychiatry) |

| Refer for medication assisted treatment (e.g., buprenorphine) |

| Treatment of co-morbid depression |

| Primarily mutually agreed upon |

| Acupuncture |

| Co-management (pain co-managed by primary care and specialists) |

| Opioid rotation |

| Psychotherapy or other counseling |

| Supervised substance use treatment programs |

| TENS unit |

Strategies mentioned by patients during this study are listed in alphabetical order. This list is not meant to be comprehensive and includes strategies that may not be consistent with good medical practice. Strategies are categorized based on patients’ report of who initiated the strategies.

Patients reported discussing only a small fraction of strategies with clinicians, though discussion was required for strategies that involved prescriptions or referrals. Many patients reported minimal or no advice from clinicians about how to manage the pain, withdrawal, and decreased opioid supply associated with tapering, and so devised strategies on their own to solve these problems.

Most patients maintained an opioid “stash” for unexpected spikes in pain or delayed opioid refills: “it doesn’t take much to realize you need to hoard something … You have to take care of yourself, you have to advocate for your needs.” Several patients described the benefits of a stash as primarily psychological, because having an emergency supply helped patients manage fears of uncontrolled pain and opioid deficits. Stashes were mostly clandestine; however, one patient reported that his clinician gave him an extra two weeks’ supply of opioids at the start of tapering to assuage the patient’s fears about unexpected pain flares and delayed opioid refills.

Tapering outcomes

Our model includes tapering outcomes for patient behaviors and attitudes. Patient behaviors comprise observable measures related to opioid tapering, such as prescribed opioid dose or patient-reported opioid consumption. Patient attitudes include willingness to taper or attitudes about tapering. These outcomes can be measured by questionnaires, pill counts, or chart abstraction. Tapering is a dynamic process, so most studies evaluating tapering interventions should collect multiple (or at least pre and post) outcome measures.

DISCUSSION

This study characterized patients’ experiences with opioid tapering and produced a conceptual model of patients’ tapering experiences. Our findings advance understanding of opioid tapering by showing that patients experience tapering as a dynamic, non-linear process affected by changes in their social relationships, emotional state, and health status. Our study is the first to document the substantial amount of physical, mental, and emotional effort most patients must expend during tapering, much of which is not discussed with clinicians.

Recommendations for clinicians

Based on our findings and conceptual model, we recommend several communication strategies primary care clinicians can use to foster productive, patient-centered discussions about tapering and to avoid unnecessary opioid prescribing. Additional research is needed before these strategies can be considered “best practices,” but these strategies should be helpful for clinicians given widespread clinical and institutional pressures to taper patients off long-term opioids9, 10 and the lack of empirically-based advice for how to negotiate tapering with patients.2

Identify the social, emotional, and health factors that will impact patients’ tapering. Patients’ experiences with tapering are largely shaped by how tapering affects their everyday lives, so an effective tapering plan must take these factors into account. When discussing tapering, clinicians should ask about their patient’s daily activities and family responsibilities, including any changes anticipated in the near future. Identifying perceived tradeoffs between opioid use and work or driving is particularly important. Patients who perceive opioids as necessary for their job will likely resist tapering, while patients restricting their driving due to opioid use may be receptive to the prospect of increased mobility.

Address patient fears about tapering, including fears of abandonment. Fears of uncontrolled pain and withdrawal were nearly universal in our study. Clinicians should anticipate and openly discuss these fears with patients before starting tapering. Potential strategies for addressing patient fears include distinguishing fear of pain from the anticipation of pain29 and promising not to leave the patient in uncontrollable pain. Another promising strategy is citing emerging evidence that tapering is not associated with worse pain and may lead to improved functional status.8, 13 Clinicians can address fears of withdrawal by providing anticipatory guidance and promising to slow, pause, or adjust tapering to minimize withdrawal symptoms. Multiple patients expressed the fear (or the experience) of being unilaterally cut off from opioids and abandoned by their clinician. Clinicians should address this fear directly and commit to non-abandonment of patients. Non-abandonment requires negotiating a mutually acceptable tapering plan, which may require multiple visits and input from specialists and allied health professionals.

Only propose tapering when you believe it is in the patient’s best interest. The importance of mutual honesty was a common theme in our data. Several patients were suspicious of clinicians who justified tapering by citing institutional or government policies. Despite such pressures, clinicians have a responsibility (endorsed by clinical guidelines9, 10) to recommend tapering only when indicated based on evaluation of clinical risks and benefits to the patient. Citing clinic policies rather than engaging with patients about (actual and perceived) risks and benefits of tapering may undermine the patient-clinician relationship. Patients are more likely to agree to taper when they believe clinicians are acting in patients’ best interest.23

Tell patients what to expect when tapering and help them identify strategies to manage tapering. Clinicians should advise patients about what to expect when tapering and provide educational resources when appropriate. Patients in our study often reported suffering withdrawal symptoms for months. If confirmed in other studies, these findings suggest that the duration of withdrawal symptoms may be longer than commonly appreciated. Tapering by 10–20% every 2–4 weeks may be too fast for many patients, especially patients with clear physiologic dependence. Clinicians should work with patients to identify strategies tailored to patients’ social, emotional, and health needs.

Develop an individualized tapering plan with provisions for making adjustments based on patient’s response. Taking time to identify the social, emotional, and health factors likely to affect tapering is critical for developing an individualized plan. Clinicians should advise patients that tapering is a dynamic process subject to adjustment along the way and make plans for checking in at regular intervals. For example, patients in our study expected clinicians to be willing to pause or temporarily reverse tapering during pain flares.

These recommendations are consistent with findings from a recent study of patient-clinician communication about opioid tapering that found patients want individualized counseling about tapering, input into tapering plans, and non-abandonment.22 Our study depended on in-depth interviews rather than transcripts of clinic visits, so our findings complement this prior study and add to an emerging literature on what constitutes effective patient-clinician communication about opioid tapering.

Conclusion

Our study adds to the few published studies of patients’ tapering experience. Frank et al.12 cataloged patient-reported barriers and facilitators to opioid tapering. Our findings build on this work by describing how patients actually experience the tapering process. For example, patients may be willing to attempt tapering during one visit, but their willingness will fluctuate as circumstances change and tapering progresses. This study also highlights the importance of patients’ everyday lives in shaping patient attitudes about tapering and the tapering strategies patients employ. The contrast between patients’ day-to-day experience with tapering and discussions with clinicians focused on opioid prescribing echoes Mishler’s contrast between the voice of medicine and the everyday lifeworld.26

Another key finding is that fear and the need to manage fear looms large in most patients’ experiences of tapering. Tapering requires patients to exert more energy managing opioids and pain, which heightens fears of uncontrolled pain or withdrawal. These findings are consistent with cognitive science research that suggests anticipation of pain can sometimes be more unpleasant than the pain itself.29 The increased effort required to manage pain, opioids, emotions, and to perform activities during tapering impacts patients’ identities. Our data indicate that successful tapering requires learning to manage pain and get through the day with fewer opioids in addition to constructing an identity that incorporates self-identity and self-worth despite persistent pain and functional limitations. These findings are consistent with sociological research demonstrating that long-term illness can result in either loss of self7 or a reconstructed identity.6

Our study has limitations. Patients were from one health system, had back and/or neck pain, and were prescribed opioids by primary care physicians. Study findings may not generalize to other contexts. However, patients were drawn from multiple clinics and clinicians. Our study is subject to possible selection bias; however, the study goal was to capture the range of patient experiences related to opioid tapering rather than to recruit a statistically representative sample. Thus, our conceptual model and recommendations are likely relevant to other primary care patients on long-term opioids for chronic neck and back pain. We did not abstract medical record data about changes in opioid dose or pain over time; recent quantitative studies addressing this question have found that patients’ pain and functional status remain stable or improve slightly after tapering.8, 13 Finally, our study did not directly address substance use disorder. While some patients with opioid use disorder may need referral for medication assisted treatment, many patients taking long-term opioids, even patients with persistent dependence, can be safely tapered down or off opioids.

The conceptual model presented in this study can inform future studies and can also be refined as research on opioid tapering develops. While not definitive, the clinical recommendations presented here can inform the design of interventions and communication training programs aimed at improving tapering outcomes by fostering effective, patient-centered discussions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R21DA042269 and K23DA043052. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banta-Green CJ, Von Korff M, Sullivan MD, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Saunders K: The prescribed opioids difficulties scale: a patient-centered assessment of problems and concerns. Clin J Pain 26:489–97, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berna C, Kulich J, Rathmell JP: Tapering Long-term Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence and Recommendations for Everyday Practice. Mayo Clin Proc 90:828–42, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braden JB, Fan MY, Edlund MJ, Martin BC, DeVries A, Sullivan MD: Trends in use of opioids by noncancer pain type 2000–2005 among Arkansas Medicaid and HealthCore enrollees: results from the TROUP study. J Pain 9:1026–35, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brault M, Hootman J, Helmick C, Armour B: Prevalence and Most Common Causes of Disability Among Adults--United States, 2005. MWMR 58:421–6, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, Jamison RN: Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain 130:144–56, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassell EJ: The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charmaz K: Good Days, Bad Days: The Self in Chronic Illness and Time. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darnall BD, Ziadni MS, Stieg RL, Mackey IG, Kao MC, Flood P: Patient-Centered Prescription Opioid Tapering in Community Outpatients With Chronic Pain. JAMA Internal Medicine 178:707–8, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Veterans Affairs / Department of Defense: VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R: CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA 315:1624–45, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esquibel AY, Borkan J: Doctors and patients in pain: Conflict and collaboration in opioid prescription in primary care. Pain 155:2575–82, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank JW, Levy C, Matlock DD, Calcaterra SL, Mueller SR, Koester S, Binswanger IA: Patients’ Perspectives on Tapering of Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Pain Med 17:1838–47, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank JW, Lovejoy TI, Becker WC, Morasco BJ, Koenig CJ, Hoffecker L, Dischinger HR, Dobscha SK, Krebs EE: Patient Outcomes in Dose Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Therapy: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 167:181–91, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia MC, Dodek AB, Kowalski T, Fallon J, Lee SH, Iademarco MF, Auerbach J, Bohm MK: Declines in Opioid Prescribing After a Private Insurer Policy Change - Massachusetts, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1125–31, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R: Persistent pain and well-being - A World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA 280:147–51, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy GP, Jr., Zhang K, Bohm MK, Losby J, Lewis B, Young R, Murphy LB, Dowell D: Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:697–704, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayden JA: The Health Belief Model In Introduction to Health Behavior Theory, 2nd ed. Burington MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2014, p. 63–106. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry SG, Bell RA, Fenton JJ, Kravitz RL: Goals of Chronic Pain Management: Do Patients and Primary Care Physicians Agree and Does it Matter? Clin J Pain 33:955–61, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holstein JA, Gubrium JF: The active interview. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy LC, Binswanger IA, Mueller SR, Levy C, Matlock DD, Calcaterra SL, Koester S, Frank JW: “Those Conversations in My Experience Don’t Go Well”: A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Provider Experiences Tapering Long-term Opioid Medications. Pain Med, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu JW, Sutherland JM, Asch SM, Kroenke K: Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med 24:733–8, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthias MS, Johnson NL, Shields CG, Bair MJ, MacKie P, Huffman M, Alexander SC: “I’m Not Gonna Pull the Rug out From Under You”: Patient-Provider Communication About Opioid Tapering. J Pain 18:1365–73, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthias MS, Krebs EE, Bergman AA, Coffing JM, Bair MJ: Communicating about opioids for chronic pain: A qualitative study of patient attributions and the influence of the patient-physician relationship. European Journal of Pain 18:835–43, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, Huffman MA, Stubbs DL, Sargent C, Bair MJ: The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers’ perspectives. Pain Med 11:1688–97, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles MB, Huberman AM: Qualitative data analysis : an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishler EG: The Discourse of Medicine: Dialectics of Medical Interviews. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudd R, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM: Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR 64:1378–82, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L: Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:1445–52, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Story GW, Vlaev I, Seymour B, Winston JS, Darzi A, Dolan RJ: Dread and the disvalue of future pain. PLoS computational biology 9:e1003335, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upshur CC, Bacigalupe G, Luckmann R: “They don’t want anything to do with you”: Patient views of primary care management of chronic pain. Pain Med 11:1791–8, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.