Abstract

Objectives: The mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-1 is a serious threat to global human and animal health. The composite transposon Tn6330 and its circular intermediate were proposed to be involved in the spread of mcr-1 but their roles remain poorly understood.

Methods: To further explore the intermediates during the transposition of Tn6330, we engineered Escherichia coli strains that carry an intact Tn6330 transposon or its deletion derivatives. PCR assays were performed to detect IR-IR junctions and possible circular intermediates. We carried out transposition experiments to calculate transposition frequency. The transposition sites were characterized by whole genome sequence and ISMapper-based analyses.

Results: The presence of an intact Tn6330 was demonstrated to be essential for the successful transposition of mcr-1, although both Tn6330 and Tn6330-ΔIR could form circular intermediates. The insertion sequence junction structure was observed in all constructed plasmids but the ISApl1 dimer was only formed in one construct containing an intact Tn6330. The average frequency of mcr-1 transposition in an E. coli strain possessing an intact Tn6330 was ∼10-6 per transformed cell. We identified 27 integration sites for the Tn6330 transposition event. All the transposition sites were flanked by 2 bp target duplications and preferentially occurred in AT-rich regions.

Conclusion: These results indicate that mcr-1 transposition relies on the presence of an intact Tn6330. In addition, formation of the tandem repeat ISApl12 could represent a crucial intermediate. Taken together, the current investigations provide mechanistic insights in the transposition of mcr-1.

Keywords: transposition mechanism, mcr-1, circular intermediate, ISApl1, colistin resistance

Introduction

Polymyxins are cationic antimicrobial cyclic polypeptides that have been reintroduced as a final clinical option for carbapenem-resistant bacteria (Li et al., 2006; Poirel et al., 2017a). The mobilized colistin resistance mcr-1 gene encodes a phosphoethanolamine (PEA) lipid A transferase that catalyzes PEA addition to the 4′-phosphate of lipid A glucosamine moieties (Gao et al., 2016; Feng, 2018; Wei et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018). This modification confers bacterial resistance to polymyxin (Liu et al., 2016). Since its discovery, mcr-1 has been detected in over 50 countries and its reservoirs include humans, animals, and foods and associated environments (Sun et al., 2017b; Shen et al., 2018). The coexistence of MCR-1 and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) or carbapenemases poses a challenge to public health safety and clinical therapies (Sun et al., 2018).

The mcr-1-bearing plasmids are diverse although the mcr-1 gene is often accompanied by a highly active 1,070 bp ISApl1 element (Sun et al., 2017a; Wang et al., 2018). ISApl1 belongs to the IS30 family containing a 307-amino-acid-long DDE-type transposase surrounded by imperfect terminal inverted repeat sequences (21/27 nucleotide identity) (Tegetmeyer et al., 2008). In general, the mcr-1-pap2 cassette lacks a flanking ISApl1, possesses one ISApl1 immediately upstream or is flanked by two ISApl1 elements. The ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2-ISApl1 transposable cassette was named Tn6330 (Li et al., 2017).

The mcr-1 gene was most likely mobilized by ISApl1 mediated composite transposon (Tn6330) (Snesrud et al., 2016, 2018). To demonstrate the function of the composite transposon Tn6330, Poirel et al. (2017b) constructed Tn6330.2 in which the mcr-1 gene was inactivated with a blaTEM-1 insertion, and characterized Tn6330 participating in the mobilization of mcr-1 gene. A circular intermediate comprised of ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 was identified as essential for mcr-1 mobilization and was generated from the downstream ISApl1 (Li et al., 2017). However, a circular intermediate does not necessarily require the complete ISApl1. A circular intermediate originating from a truncated ISApl1 immediately downstream of mcr-1 could also be detected (Zhao et al., 2017). Therefore, the circular intermediate for mcr-1 mobilization is unclear.

Insertion sequence (IS) dimers can be detected by the presence of an inverted repeat (IR) junction, a full copy IS adjacent to a truncated IS or a circular IS (Olasz et al., 1993; Kiss and Olasz, 1999). For example, this has found experimentally by the detection of IR-IR junctions formed by site specific dimerization in tandem IS30 elements (Kiss and Olasz, 1999). However, it is not known whether an ISApl1 dimer is formed during Tn6330 transposition. To address this issue, we engineered a collection of plasmids bearing Tn6330 and its derivatives and demonstrated that transposition of mcr-1 relied on intact Tn6330 for efficient integration into the Escherichia coli genome. Additionally, we found a tandem ISApl1 repeat ISApl12-mcr-1-pap2 that could represent a crucial intermediate during Tn6330 transposition.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Escherichia coli MG1655 (wild-type) and E. coli MG1655 (recA::Km) strains were used as host strains in the transposition experiments (Table 1; Gerdes et al., 2003). E. coli strain BW25141 strain contained the pir gene possessing an R6K replication origin (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000) and was used as a host to construct suicide plasmids bearing Tn6330 and derivatives (Table 1). The E. coli swine strain CBJ3C was used as a template to amplify Tn6330 (Table 1). The Tn6330 upstream ISApl1 (5′-TTTCCAA-3′) and downstream ISApl1 (5′-CTTCCAA-3′) differed by only one bp (underlined) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli MG1655 (wild-type) | K-12 strain F- λ- ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 | Gerdes et al., 2003 |

| E. coli MG1655 (recA::Km) | K-12 strain F- λ- ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 recA | Gerdes et al., 2003 |

| E. coli BW25141 | F-, ΔaraDB567, ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB3), ΔphoBR580, λ-, galU95,ΔuidA3::pir+, recA1, endA9(del-ins)::FRT, rph-1, ΔrhaDB568, hsdR514 | |

| E. coli CBJ3C | Clinical isolate carrying Tn6330 | |

| pSV03 | CmR, replication origin from E. coli plasmid R6K; requires the R6K initiator protein pir for replication | This study |

| pKD4 | Lambda red recombinase system template plasmid | |

| pKD46 | Lambda red recombinase system template plasmid | |

| pJS01 | Suicide plasmid (R6K replication origin) contains ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2-ISApl1 | This study |

| pJS02 | Suicide plasmid (R6K replication origin) contains Tn6330 (ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2-ISApl1) without upstream IRL and downstream IRR | This study |

| pJS03 | Suicide plasmid (R6K replication origin) contains ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 | This study |

| pJS04 | Suicide plasmid (R6K replication origin) contains mcr-1-pap2- ISApl1 | This study |

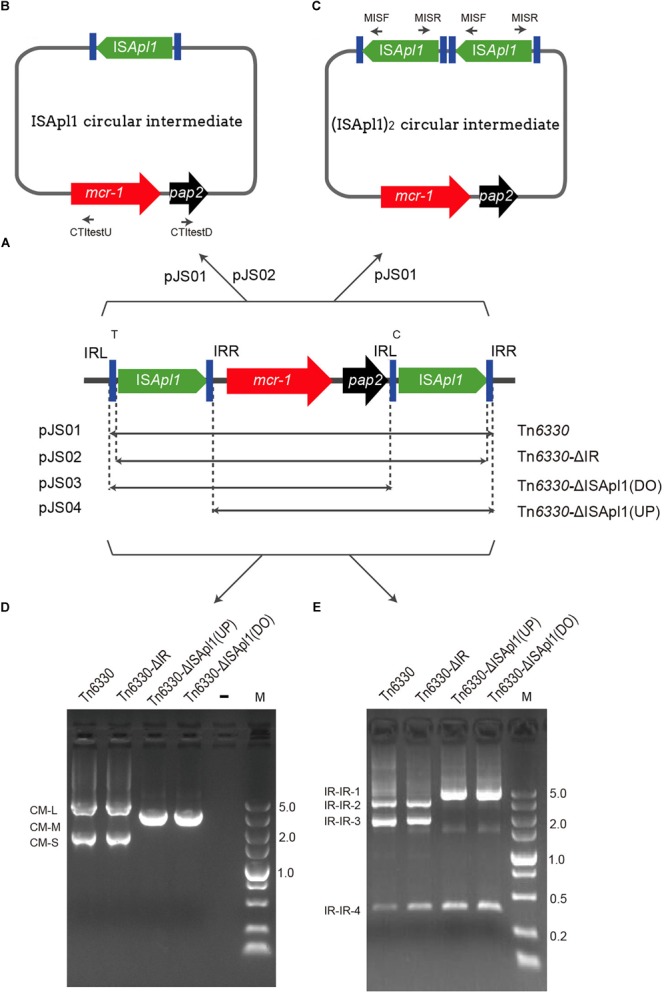

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of mcr-bearing transposons and verification of the presence of an ISApl1- mediated circular intermediate. (A) Structures of Tn6330 derivatives and plasmid hosts. (B) A circular intermediate and (C) An ISApl1 dimer circular intermediate. (D,E) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products generated from screening assays using Escherichia coli strains containing the indicated Tn constructs. (D) Reverse PCR assay using primers CTI test U and CTI test D to identify ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 intermediates. CM-L (circular form) represents the remnants of the pap2, ISApl1 backbone of the suicide plasmid, ISApl1 and part of mcr-1. (E) PCR products generated using primers MISF and MISR to screen for the presence of IR-IR junctions.

Plasmid Construction

Tn6330, Tn6330-ΔIR, Tn6330-ΔISApl1(DO) (downstream) and Tn6330-ΔISApl1(UP) (upstream) were cloned into suicide plasmid pSV03 (Rakowski and Filutowicz, 2013) and were named pJS01, pJS02, pJS03, and pJS04, respectively (Table 1, Figure 1A, and Supplementary Figure S1). Primers used for plasmid constructions are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used for plasmid construction.

| Primer | Sequence ( 5′ → 3′)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| TUtestF-BglII | TACGCAGATCTACTACTGTGGCTAAGCCTCAAC | This study |

| TUtestR-XhoI | TACGCCTCGAGACGGAGAGTAACAACACGATGC | This study |

| R6K-BglII | TACGCAGATCTCCATGTCAGCCGTTAAGTGT | This study |

| R6K-XhoI | TACGCCTCGAGGTTGATCGGCACGTAAGAGG | This study |

| R6K-BamHI | TACGCGGATCCGTTGATCGGCACGTAAGAGG | This study |

| R6K-EcoRI | TACGCGAATTCCCATGTCAGCCGTTAAGTGT | This study |

| P1 | GGCTGCAGACGCACAGCA | This study |

| IR-F | TTTTTTGAAGTAAACTTCATAAGGTGTTTTCCAACC | This study |

| CmR-F | ACCTTATGAAGTTTACTTCAAAAAAAGACTAAAAGAGAAGGGAGT | This study |

| Sac-R | CCAAGCGAGCTCGATATCAA | This study |

| Sac-F | TTGATATCGAGCTCGCTTGG | This study |

| CmR-R | ATTATATTCTAGTTGATGAGTACTTCTTTTTCTCTTTAAGTTGAGGCTTAGCC | This study |

| IR-R | AAAAAGAAGTACTCATCAACTAGAATATAATTTTGTTTCCACAC | This study |

| P2 | ATTGCTGTGCGTCTGCAGCCA | This study |

| UP-TF | AGACTAAAAGAGAAGGGAGTG | This study |

| UP-TR | CGATTAAACTTGTTCACCCTTC | This study |

| DO-F | CTCTCAAGTGTATATTCAGTATGGG | This study |

| DO-R | CTCTTTAAGTTGAGGCTTAGCC | This study |

| CTItestU | CGATGATAACAGCGTGGTGATC | This study |

| CTItestD | TTGCCGATGCTTGATAGTATGC | This study |

| MIS-F | CAATCAGTGGAGCGAAGTTG | This study |

| MIS-R | CTGTTTTGTGCGTTCGTTGC | This study |

aRestriction sites are underlined.

In pJS01, the structure of ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2-ISApl1 and flanking sequences were amplified by PCR using primers TUtestF-BglII and TUtestR-XhoI with E. coli CBJ3C template DNA. Primers R6K-BglII and R6K-XhoI were used to amplify the backbone of pSV03, which includes the conditional replication origin R6K and chloramphenicol resistance gene (CmR). A ligation was performed giving rise to recombinant plasmid pJS01. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BW25141 and selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates supplemented with 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm). The integrity of both ISApl1 elements and mcr-1 was confirmed by PCR and sequence analysis.

The plasmid pJS02 was used to amplify a partial mcr-1, pap2, and ISApl1-ΔIRR (IR right) fragment using primers P1 and IR-F. It was constructed using a fragment containing CmR that was amplified using primers CmR-F that lacked the 27 bp IRR and SacR containing a SacI site. The amplicons were connected by overlapping PCR resulting in a DNA fragment of the downstream ISApl1 lacking the 27 bp IRR that was bounded by PstI and SacI restriction enzyme sites. The sequence containing a fragment of the upstream ISApl1 without a 27bp IRL (IR left) containing PstI and SacI restriction sites at the ends was obtained in the same manner using primers Sac-F, CmR-R, IR-R and P2. The amplified fragments were digested with PstI and SacI and joined using T4 ligase. Plasmid pJS02 was confirmed as described above for pJS01.

Plasmids pJS03 and pJS04 were derived using primers UP-TR, UP-TF and DO-F and DO-R to amplify DNA fragments lacking the downstream copy of ISApl1 or upstream copy of ISApl1, respectively. After self-ligation, the plasmids were screened and confirmed as for pJS01 above.

The Detection of Circular Intermediate and IR-IR Junction

All constructed plasmids carrying Tn6330 or its derivatives were tested for the ability of ISApl1-mcr-1 to generate circular forms using reverse PCR with primers CTItestU and CTItestD that targeted mcr-1 and pap2, respectively. To identify IR-IR junctions, PCR and Sanger sequencing were performed using primers MIS-F and MIS-R which were directed outward from ISApl1 (Table 2).

Transposition Assays

Transposition assays were performed as previously described (Bontron et al., 2016). In brief, suicide plasmids pJS01, pJS02, pJS03, and pJS04 were electroporated into E. coli MG1655 (wild-type) and E. coli MG1655 (recA::Km) using a Biorad MicroPulser (Hercules, CA, United States) and the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. The bacteria were suspended in 1ml LB and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with agitation and serially diluted onto LB-agar containing 2 μg/ml colistin to select for transposition events. The presence of the full-length transposon Tn6330 was confirmed using PCR with primers in Supplementary Table S1. The transposition frequencies were calculated by dividing the number of transposition events by the number of transformed cells in triplicate (Milewska et al., 2015).

Mapping of Transposon Insertion Sites

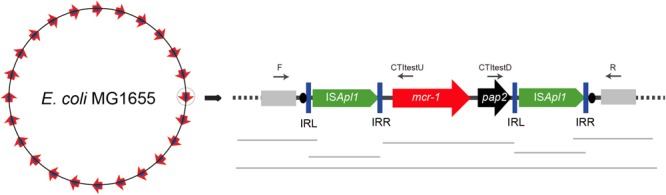

Transposon insertion sites in E. coli MG1655 (recA::Km) were identified from random genomic DNA samples of each confirmed transposant prepared from overnight cultures using the TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (Tiangen, Dalian, China). The DNA of all the transposants was then mixed together into a single pool and a 300-bp library was constructed for Illumina paired-end sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Illumina sequences were assembled de novo using SOAP software (Luo et al., 2012). The contigs carrying mcr-1 and ISApl1 fragments were concatenated through the ISmapper analysis (Hawkey et al., 2015). Then the gaps were closed using PCR mapping and Sanger sequencing as shown in Figure 2. The primers targeted in the sequences of chromosome and mcr-1-pap2 was designed in different insert regions (Supplementary Table S1 and Table 1) to determine transposition sites.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic for determination of the transposition site by WGS and PCR. Sequences of E. coli MG1655 are shown as rectangles in light gray. The inverted repeats (IRL and IRR) are represented as blue vertical bars and DRs as black ovals.

To characterize the genetic context of Tn6330 in clinical strains, the sequences carrying Tn6330 in GenBank were collected. For each transposition event, the relative frequencies of each A and T, and G and C of the region extending from 50 nucleotides upstream to 50 nucleotides downstream from the insert target were calculated and plotted on a line graph (Tang et al., 2017). The pictures of the relative frequencies of the bases at each position were generated with the Pictogram program1.

Results

Transposition of the Composite Transposon

We identified the transposition abilities of the Tn6330 derivatives by cloning into suicide plasmids that were then electroporated into strain BW25141 (pir+). These suicide plasmids were transformed into two E. coli recipient strains MG1655 (wild-type) and MG1655 (recA::Km). Survival was contingent upon transposition of the selectable markers into the host genome. The transposition frequencies of pJS01 into both E. coli strains occurred at 2.7 × 10-6 per transformed cell. PCR and Sanger sequencing results showed that the downstream (5′-CTTCCAA-3′) and upstream (5′-TTTCCAA-3′) of ISApl1 in Tn6330 in the insertion sites were different, indicating complex transposition events (data not shown). In contrast, all other constructs failed to generate cell survival in the presence of colistin (2 μg/ml). This indicated that Tn6330-ΔIR, Tn6330-ΔISApl1(DO), and Tn6330-ΔISApl1(up) could not transpose successfully.

Interestingly, we found evidence for the formation of circular intermediates containing the ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 structure (CM-S) from plasmids harboring Tn6330 and Tn6330-ΔIR. However, if the upstream or downstream ISApl1 was removed, no circular form could be detected (Figures 1B,D and Table 3).

Table 3.

Transposition frequencies of suicide plasmids bearing mcr-1 genes.

| Plasmid | Transposase | Reverse PCR | IR-IR junction | Transposition frequency (wild type)a | Transposition frequency (recA::Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pJS01 | + | + | + | 2.78 × 10-6 | 2.71 × 10-6 |

| pJS02 | – | + | + | – | – |

| pJS03 | + | – | + | – | – |

| pJS04 | + | – | + | – | – |

All these transposition events generated IR-IR junctions were separated by 2 bp spacers (Figures 1C,E, 3). This would be possible through the formation of ISApl1 dimers (pJS01, Figure 1C), a truncated ISApl1 next to a truncated ISApl1 (pJS02) or a circularized ISApl1 that was possible with all constructs (Kiss and Olasz, 1999).

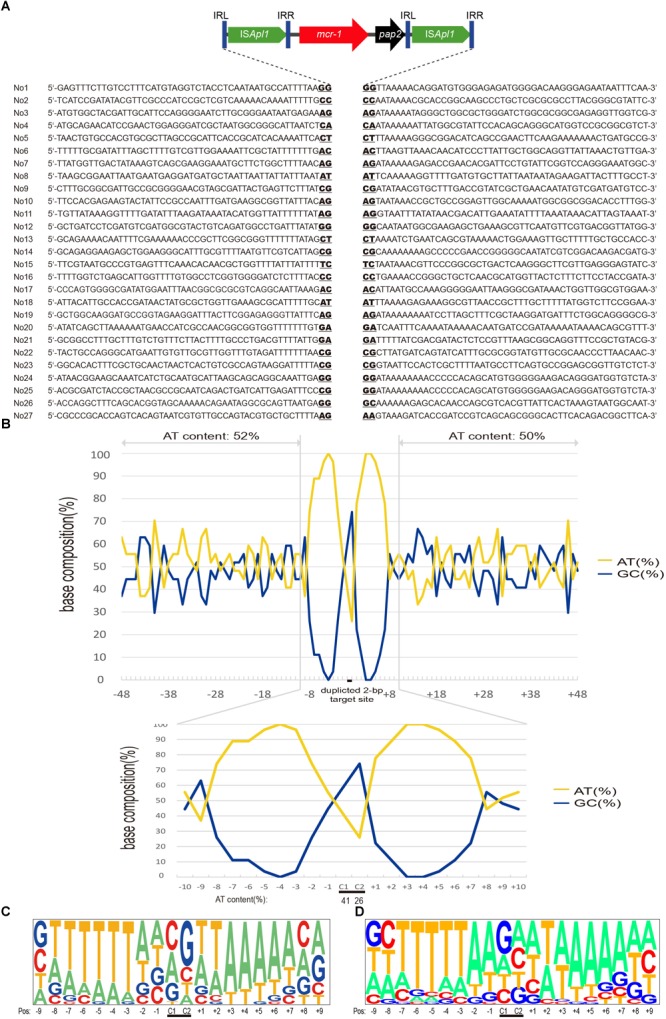

FIGURE 3.

Target site analyses of Tn6330 transposons. (A) Molecular characterization of 27 transposition events of Tn6330 transposons in E. coli MG1655 (recA::Km). The duplicated 2-bp target site is underlined in the context of the surrounding 48 nucleotides upstream and downstream of the target sites. (B) Statistical( analyses of the 27 transposition sites. The percentage of AT and GC at each position from 48 nucleotides upstream to 48 nucleotides downstream of the target site are shown. The 2-bp duplicated target site (c1 and c2) are indicated by black bars. The AT and GC percentages of regions spanning positions –48 to –3 and positions +3 to +48 and that of the region spanning positions –2 to 2 are indicated in the upper and lower graphs, respectively. Relative nucleotide frequencies at each target site deduced from the (C) 27 experimental transposition events shown in (A) and (D) from 26 Tn6330 transposons in clinical isolates obtained from GenBank (Supplementary Table S2).)

Target Site Specificity

Whole genome sequence (WGS) and ISMapper-based analyses revealed 27 integration sites. The Illumina reads have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. SRR8365224. The insert locations of the mcr-1 gene were further confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. The majority of these events (24/27) generated 2-bp duplications and occurred in AT-rich regions with a high preference for insertion between T and A. The mean AT content extending in each direction from the 2-bp target sites (–50 to –2 bp and +2 to +50 bp) were 52 and 50%, respectively (Figure 3). In addition, the AT content increased nearer the target site and was 100% at positions –4, +3 and +4 and 74 to 96% at positions –7, –6, –5, –2, +1, +2, +5, +6 and +7. At the duplicated target site positions (c1 and c2) the AT content was lower (26 to 41%) (Figure 3B).

Distribution of Tn6330-Like Transposons in Enterobacteriaceae

To further characterize the transposon events in clinical strains, we collected sequences harboring the Tn6330-like structures from GenBank in isolates from more than ten regions including China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, United States, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Argentina, and Canada (Supplementary Table S2). We found that 47 sequences had 2-bp target directed repeats, a characteristic signature of transposition events of Tn6330-like transposons. The AT preferences of Tn6330 insertions were similar to that in vitro mobilization assays presented above (Figure 3D).

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated the functionality of Tn6330 transposition from plasmids where cell survival was dependent on transposition of the mcr-1 selective marker. The intact Tn6330 in plasmid pJS01 transposed efficiently into the E. coli chromosome. Transposition occurs via a highly reactive intermediate such as IS302 and provides a molecular model for IS30-like transposition. This also relied on a circular intermediate carrying an active IR-IR junction (Olasz et al., 1993; Kiss and Olasz, 1999). The ISApl1 element in Tn6330 belongs to the IS30 family so we examined the role of ISApl12 carrying joined IRs in ISApl1- mediated transposon. Previous studies provided evidence that the reverse PCR amplicon ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 acted as a circular intermediate (Li et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). However, this could not distinguish between that structure and (ISApl1)2-mcr-1-pap2. All four of our plasmid constructs generated IR-IR junctions.

The genuine IS30-like circular intermediate of Tn6330 composed of (ISApl1)2-mcr-1-pap2 was only formed from pJS01 (Figure 1C). This was dependent upon the ISApl1 IR-IR junction and the production of the transposase for successful transposition into the E. coli chromosome (Kiss and Olasz, 1999). Plasmids pJS02, pJS03 and pJS04 could not form the ISApl12-mcr-1-pap2 circular intermediates and failed to transpose. This would also explain that mcr-1 in the absence of flanked copies of ISApl1 or just one copy of ISApl1 originated from an ancestral Tn6330 (Snesrud et al., 2018). The transposition of mcr-1 relied on an intact Tn6330.

Transposition frequencies of suicide plasmids carrying Tn6330 were high at rates of 10-6 per transformed cell both in wild type and recA mutant MG1655 strain. The relatively high Tn6330 transposition frequency together with frequent insertion into transmissible plasmid targets might explain why the mcr-1 gene is globally prevalent. Tn6330 has been found in E. coli, Salmonella enterica, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter freundii, and Citrobacter braakii (Supplementary Table S2). The composite transposon Tn6330 might lose one or both copies of ISApl1 through illegitimate recombination giving rise to different types of genetic contexts such as ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2, mcr-1-pap2, ΔTn6330 and others (Snesrud et al., 2016). Loss of ISApl1 seems to be conducive to mcr-1 maintenance increasing the stability of this gene in the host genome or plasmids and raising the risk of mcr-1 dissemination.

The target site of Tn6330 was AT rich in the 6 bp surrounding the duplicated target site. In E. coli clinical isolates, the same features were present both in plasmids and chromosomal regions consistent with previous works (Snesrud et al., 2016, 2018; Poirel et al., 2017b). Both the experimental transposants and E. coli clinical isolates showed a high frequency of T on the upstream and A on the downstream sides of the Tn6330 target site. These findings contrast with previous descriptions that indicated target site duplication always carried a C or a G or both suggesting a relatively even distribution of A, T, G and C.

Though Poirel et al. (2017b) have demonstrated the mobility of the mcr-1 gene by transposition, some differences exist in our study: (1) we found the suicide plasmids harboring mcr-1 could successfully transpose into the bacterial chromosome using the colistin resistant phenotype during the process of transposition. We found no visible toxic effects to the presence of MCR-1. Toxic effects of MCR-1 that limited colonization of mcr-1 in regular bacterial cells might be caused by high plasmid copy number (Yang et al., 2017). (2) We characterized 27 transposon sites using WGS and ISMapper. Compared with previous digestion and inverse PCR strategies, the ISMapper method might be more convenient and efficient (Poirel et al., 2017b). (3) The regions of the downstream ISApl1 (CTTCCAA) were different from the upstream ISApl1 (TTTCCAA) in all the transposants; the same as initial Tn6330 in pJS01. This result suggested that the transposition events were not from the ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 circular form. This was further evidence for an ISApl1 dimer-mediated composite transposon (Snesrud et al., 2018). In addition, our study for the first time indicates that an ISApl1 dimer plays a crucial role as a genuine circular intermediate. This contrasts with previous studies indicating that the ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 circular form results in the transposition of mcr-1 (Li et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017). A reverse PCR amplicon does not completely characterize a circular intermediate since it cannot identify the IS-IS junction.

In summary, our results further verified that the transposition of mcr-1 is only mediated by an intact Tn6330 but not the amplicon identified by reverse PCR, the ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 circular form. In addition, the ISApl1 dimer ISApl12-mcr-1-pap2 represents a crucial intermediate in mcr-1 transmission. Future studies will focus on the regulatory mechanisms of Tn6330 transposition in the search for a viable path to block the spread of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1.

Author Contributions

JS designed this project. Y-ZH, Y-YM, X-PW, and Y-YG performed the experiments. Y-ZH, X-PLi, YF, and JS analyzed the data. X-PLi and R-YS made the figures. X-PLi wrote this manuscript. JL, X-PLiao, YF, and JS edited and revised the manuscript. Y-HL coordinated the whole project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer BZ declared a shared affiliation, with no collaboration, with one of the authors, YF to the handling Editor at the time of review.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0501300), the Program of Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of Ministry of Education of China (IRT13063), and Pearl River S&T Nova Program of Guangzhou (Grant No. 201610010036).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00015/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bontron S., Nordmann P., Poirel L. (2016). Transposition of Tn125 encoding the NDM-1 carbapenemase in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 7245–7251. 10.1128/AAC.01755-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. (2018). Transferability of MCR-1/2 polymyxin resistance: complex dissemination and genetic mechanism. ACS Infect. Dis. 4 291–300. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R., Hu Y., Li Z., Sun J., Wang Q., Lin J., et al. (2016). Dissemination and mechanism for the MCR-1 colistin resistance. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005957. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes S. Y., Scholle M. D., Campbell J. W., Balázsi G., Ravasz E., Daugherty M. D., et al. (2003). Experimental determination and system level analysis of essential genes in Escherichia coli MG1655. J. Bacteriol. 185 5673–5684. 10.1128/jb.185.19.5673-5684.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey J., Hamidian M., Wick R. R., Edwards D. J., Billman-Jacobe H., Hall R. M., et al. (2015). ISMapper: identifying transposase insertion sites in bacterial genomes from short read sequence data. BMC Genomics 16:667. 10.1186/s12864-015-1860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J., Olasz F. (1999). Formation and transposition of the covalently closed IS30 circle: the relation between tandem dimers and monomeric circles. Mol. Microbiol. 34 37–52. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Nation R. L., Turnidge J. D., Milne R. W., Coulthard K., Rayner C. R., et al. (2006). Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6 589–601. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Xie M., Zhang J., Yang Z., Liu L., Liu X., et al. (2017). Genetic characterization of mcr-1-bearing plasmids to depict molecular mechanisms underlying dissemination of the colistin resistance determinant. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72 393–401. 10.1093/jac/dkw411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Y., Wang Y., Walsh T. R., Yi L. X., Zhang R., Spencer J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 161–168. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R., Liu B., Xie Y., Li Z., Huang W., Yuan J., et al. (2012). SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1:18. 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewska K., Wegrzyn G., Szalewska-Palasz A. (2015). Transformation of Shewanella baltica with ColE1-like and P1 plasmids and their maintenance during bacterial growth in cultures. Plasmid 81 42–49. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olasz F., Stalder R., Arber W. (1993). Formation of the tandem repeat (IS30)2 and its role in IS30-mediated transpositional DNA rearrangements. Mol. Gen. Genet. 239 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Jayol A., Nordmann P. (2017a). Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30 557–596. 10.1128/CMR.00064-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Kieffer N., Nordmann P. (2017b). In-vitro study of ISApl1-mediated mobilization of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e00127-17. 10.1128/AAC.00127-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski S. A., Filutowicz M. (2013). Plasmid R6K replication control. Plasmid 69 231–242. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Zhou H., Xu J., Wang Y., Zhang Q., Walsh T. R., et al. (2018). Anthropogenic and environmental factors associated with high incidence of mcr-1 carriage in humans across China. Nat. Microbiol. 3 1054–1062. 10.1038/s41564-018-0205-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snesrud E., He S., Chandler M., Dekker J. P., Hickman A. B., McGann P., et al. (2016). A model for transposition of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 by ISApl1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 6973–6976. 10.1128/AAC.01457-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snesrud E., McGann P., Chandler M. (2018). The birth and demise of the ISApl1-mcr-1-ISApl1 composite transposon: the vehicle for transferable colistin resistance. MBio 9:e02381-17. 10.1128/mBio.02381-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Fang L. X., Wu Z., Deng H., Yang R. S., Li X. P., et al. (2017a). Genetic analysis of the IncX4 plasmids: Implications for a unique pattern in the mcr-1 acquisition. Sci. Rep. 7:424. 10.1038/s41598-017-00095-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zeng X., Li X. P., Liao X. P., Liu Y. H., Lin J. (2017b). Plasmid-mediated colistin resistance in animals: current status and future directions. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 18 136–152. 10.1017/S1466252317000111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhang H., Liu Y. H., Feng Y. (2018). Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol. 26 794–808. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Li G., Liang W., Shen P., Zhang Y., Jiang X. (2017). Translocation of carbapenemase gene blaKPC-2 both internal and external to transposons occurs via novel structures of Tn1721 and exhibits distinct movement patterns. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e01151-17. 10.1128/AAC.01151-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegetmeyer H. E., Jones S. C., Langford P. R., Baltes N. (2008). ISApl1, a novel insertion element of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, prevents ApxIV-based serological detection of serotype 7 strain AP76. Vet. Microbiol. 128 342–353. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., van Dorp L., Shaw L. P., Bradley P., Wang Q., Wang X., et al. (2018). The global distribution and spread of the mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Nat. Commun. 9:1179. 10.1038/s41467-018-03205-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Srinivas S., Lin J., Tang Z., Wang S., Ullah S., et al. (2018). Defining ICR-Mo, an intrinsic colistin resistance determinant from Moraxella osloensis. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007389. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wei W., Lei S., Lin J., Srinivas S., Feng Y. (2018). An evolutionarily conserved mechanism for intrinsic and transferable polymyxin resistance. MBio 9:e02317-17. 10.1128/mBio.02317-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Li M., Spiller O. B., Andrey D. O., Hinchliffe P., Li H., et al. (2017). Balancing mcr-1 expression and bacterial survival is a delicate equilibrium between essential cellular defence mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 8:2054. 10.1038/s41467-017-02149-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F., Feng Y., Lu X., McNally A., Zong Z. (2017). Remarkable diversity of Escherichia coli carrying mcr-1 from hospital sewage with the identification of two new mcr-1 variants. Front. Microbiol. 8:2094. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.