Abstract

This study was investigated the effects of dietary supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine on the development of the gastrointestinal tract and the intestinal digestive enzyme activity in male Holstein dairy calves. Twenty calves with a body weight of 38 ± 3 kg at 1 day of age were randomly divided into four groups: a control group, a leucine group (1.435 g·l−1), a phenylalanine group (0.725 g·l−1), and a mixed amino acid group (1.435 g·l−1 leucine plus 0.725 g·l−1 phenylalanine). The supplementation of leucine decreased the short-circuit current (Isc) of the rumen and duodenum (P<0.01); phenylalanine did not show any influence on the Isc of rumen and duodenum (P>0.05), and also counteracted the Isc reduction caused by leucine. Leucine increased the trypsin activity at the 20% relative site of the small intestine (P<0.05). There was no difference in the activity of α-amylase and of lactase in the small intestinal chyme among four treatments (P>0.05). The trypsin activity in the anterior segment of the small intestine was higher than other segments, whereas the α-amylase activity in the posterior segment of the small intestine was higher than other segments. Leucine can reduce Isc of the rumen and duodenum, improve the development of the gastrointestinal tract, and enhance trypsin activity; phenylalanine could inhibit the effect of leucine in promoting intestinal development.

Keywords: Calves, Digestive enzyme activity, Gastrointestinal development, Leucine, Phenylalanine

Introduction

The gastrointestinal tract is the main place for all animals and humans to digest diets and absorb nutrients. Good development of the gastrointestinal tract can promote the digestion and absorption of nutrients by calves and improve feed utilization efficiency. Different dietary nutrient levels can affect the gastrointestinal development in calves [1,2,3], with diets with suitably high protein levels shown to promote gastrointestinal development in calves [4,5]. Leucine, as a functional amino acid [6], can activate the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway to regulate protein synthesis and catabolism in the animal body [7,8,9,10] and promote the development of the gastrointestinal tract in animals [11]; phenylalanine is an aromatic amino acid and can promote the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK) through calcium-sensing receptors [12,13]. CCK can stimulate the pancreas to synthesize pancreatic amylase, trypsin and trypsinogen, and it can further stimulate the release of pancreatic enzymes and enhance pancreatic enzyme activity [14]. Previous studies by our research team have shown that leucine and phenylalanine can regulate pancreatic enzyme synthesis and promote starch digestion in adult ruminants [15,16,17]. We hypothesized that leucine and phenylalanine may have the effect of promoting intestinal development and increase intestinal digestive enzyme activity in calves, thereby promoting the growth and development of calves. At present, there are few reports concerning the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in young ruminants, particularly reports regarding their effects on intestinal development and enzyme activity in calves. Moreover, the forestomach system in calves is not fully developed, and their digestive system is similar to that of monogastric animals. In calves, milk can directly reach the abomasum without going through the rumen and reticulum to undergo preliminary digestion, and then milk can reach the small intestine to be digested and absorbed [18], thereby avoiding changes of nutrient components in the diet caused by microorganisms in the rumen and reticulum. Taking advantage of this physiological characteristic and with slaughter testing, this study examined the effects of leucine and phenylalanine supplementation up to 8 weeks after birth on gastrointestinal tract development indices, changes in gastrointestinal tract electrophysiology, and changes in digestive enzyme activity in the intestines of calves. Meanwhile this study also explored the role of leucine and phenylalanine in the development of the gastrointestinal tract and in the regulation of intestinal digestive enzymes, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the potential supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine for the efficient production of dairy cows.

Materials and methods

The use of all animals and experimental protocols was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Animal Science and Technology, the Northwest A&F University, China.

Experimental animals and design

This experiment consisted of 20 male Holstein calves with a body weight of 38 ± 3 kg at the age of 1 day. These calves, according to a grouping pattern sorting calves with similar body weights into the same group, were randomly divided into four groups: a control group (C), a leucine group (L), a phenylalanine group (P), and a mixed amino acid group (PL, leucine + phenaylalanine). Five calves were included in each group; 8 weeks were used as the experimental duration.

The experimental treatment was achieved by supplementing leucine and phenylalanine into raw milk, followed by adjusting to an isonitrogenous diet by supplementing alanine. Leucine and phenylalanine were purchased from Hai De Amino Acids Industry Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, Zhejiang, China) and the purity was >99%. All amino acids are the L amino acids and could be absorbed by animal. The basis for the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine for the treatment groups referred to the results of the previous studies by our own research team [15,16,17]. The supplementation amount for each treatment is shown in Table 1, and the amounts added into milk were leucine 1.435 g/l, phenylalanine 0.725 g/l, and alanine 1.366 g/l.

Table 1.

Quantity of amino acids added in milk (g·l−1, DM)

| Items | Treatments1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | P | L | PL | |

| Leucine | - | - | 1.435 | 1.435 |

| Phenylalanine | - | 0.725 | - | 0.725 |

| Alanine | 1.366 | 0.975 | 0.391 | - |

Abbreviations: C, control; P, phenylalanine; L, leucine; PL, leucine and phenylalanine. Animals were fed with isonitrogenous diets, achieved by supplementing alanine.

Feeding management

The animal experiment was conducted at the calf island in Modern Farm (Baoji) Co., Ltd. The experimental diet consisted of raw milk and starter diets. After the calves were born, 4 l of colostrum were fed within 1 h. The next week served as a transitional period, the calves were manually bottle-fed 3 l of milk twice daily. During the transitional period, the amino acid supplementation was increased over a gradient of 20% per day until it reached 100% of the supplementation amount by the sixth day after birth. Weeks 2–8 served as the testing period, during which raw milk supplemented with amino acids was fed twice per day; 3.5 h of feeding was used each time for weeks 2–3, and 4 h per feeding for weeks 4–8. Starting at the third week, a starter feed was provided twice a day, and the amount of the feed offered to each calves were 210 g/d in week 3 and gradually increased to 1800 g/d in week 8, to ensure all calves consumed the feed without any refusal. The calves were provided free access to fresh drinking water.

Sample collection and index determination

The calf starter diet (Purina Co., China) consisted of corn, soybean meal, wheat bran, sugarcane molasses, calcium hydrogen phosphate, rock powder, salt, L-lysine, vitamin A, vitamin D3, vitamin E, copper sulfate, and ferrous sulfate. The methods of AOAC were used for measurements of dry matter (DM) (ID: 930.5), crude protein (CP, N × 6.25; ID 984.13), ash (ID: 942.05), calcium (ID 927.02), and phosphorus (ID 965.17) [19]. The levels of neutral detergent fiber and acid detergent fiber were determined with reference to Van Soest et al. [20]. The chemical composition of the granulated starter is shown in Table 2. Raw milk was collected once every 2 weeks, and the amino acid composition were determined according to the method by Roseiro et al. [21]. in an amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Japan) equipped with an ion exchange column. The levels (g·l−1, DM) of arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, valine, alanine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, tyrosine, glycine, serine, and proline in the raw milk were 1.429, 0.920, 1.744, 3.432, 3.055, 0.950, 1.731, 1.804, 2.372, 1.356, 2.869, 0.358, 7.605, 1.846, 0.838, 2.260, and 6.458, respectively. There was no difference in the intake of the starter food among the different treatments.

Table 2.

Nutrient levels of the starter diet fed to calves (%DM)1

| Chemical analysis | Content (%) |

|---|---|

| Dry matter | 87.06 |

| Crude protein | 20.01 |

| Crude ash | 15.47 |

| Starch | 38.79 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 12.20 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 6.20 |

| Calcium | 0.70 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.38 |

The starter diet was purchased from Purina Co., China. It contained corn, soybean meal, wheat bran, sugar cane molasses, calcium hydrophosphate, stone powder, salt, L-lysine, vitamin A, vitamin D3, vitamin E, copper sulfate, and ferrous sulfate.

When calves were 8 weeks old, after the morning feeding, they were cut off from feed, although free-choice water intake was provided. At 08:00 on the next day, these animals were killed by exsanguination. The body length and before-slaughter live weight were measured prior to slaughter. After the calves were slaughtered and skinned, the abdominal cavity was dissected, and the rumen and reticulum, omasum, abomasum, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon, and rectum were separated by cotton-thread ligation. Mesentery and extra-intestinal fat were removed, and the length of each intestinal segment was measured. After removing the contents of the stomach, the rumen and reticulum volume was measured by the drainage method. Each of the stomach compartments was rinsed with physiological saline, and each of the stomach compartments was weighed after the water was absorbed by gauze. The relative weight of each stomach compartment and the intestine-body ratio of each intestinal segment were calculated as follows:

Relative weight = Weight of stomach compartment (kg) / Body weight (kg) × 100%

Intestine–body length ratio = Intestine length (cm) / Body diagonal length (cm) × 100%

The 3 × 3 cm rumen and duodenal intestinal segments at the central part of the rumen abdominal sac and at 5 cm posterior to the front of duodenum were cut and collected for measuring the short-circuit current (Isc) using the Ussing Chamber system (World Precision Instrument, U.S.A.). Gastrointestinal tissues were washed with ice-cold normal saline and placed in Ringers buffer for 5 min in an ice bath [22]. The fascia layer was quickly peeled off, and the intestinal mucosa was fixed on the diffusion pool; the effective permeation area was 1.69 cm2. Ringers buffer that was preheated to 37°C was added at both sides, and a circulating water bath system was used to maintain the temperature; meanwhile, mixed gas (5% CO2 and 95% O2) was continuously supplied. The electrode was connected with a KCl agar salt bridge (3% agar dissolved in 3 mol/l KCl), and Isc was measured by applying a clamping voltage of 10 mV. The output signal was collected with a data logger (World Precision Instrument, USA), and the signal was recorded with Lab-Trax software.

The total length of the small intestine (from the pyloric end to the end of ileum) was set as 100%, and 10 g of intestinal chyme sample was collected at the relative positions of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% receptively [16] and stored at −80°C. For measuring the enzymes activity, the chyme was homogenized first, and then the homogenate was centrifuged to precipitate food residue. The supernatant was used for the enzyme activity determination. The activity levels of lactase, trypsin, α-amylase were determined, and the main digestive enzyme activity in the small intestinal chyme was measured using a commercial kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufactory’s protocols. Briefly, the protocols consisted of homogenization, incubation at 37°C in water bath, substrate reaction with the given reagent in microplate, recording the OD by a microplate reader, and the calculation the enzyme activity against the calibration curve.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the GLM procedure of SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The gastrointestinal developments were analyzed using the following model:

where, Yij is the response variable, μ is the overall mean, Li is the fixed effect of leucine (i = with or without), Pj is the fixed effect of phenylalanine (j = with or without), LPij is the interaction between leucine and phenylalanine, and εij is the residual error.

The digestive enzyme activities and Isc were analyzed using the following model:

where, Yijk is the response variable, μ is the overall mean, Li is the fixed effect of leucine (i = with or without), Pj is the fixed effect of phenylalanine (j = with or without), Sk is the effect of the kth site for digestive enzyme activities and the kth time (min) for Isc; LPij is the interaction between leucine and phenylalanine, LPSijk is the interaction among leucine, phenylalanine and site, and εijk is the residual error.

When significant interactions were detected, treatment effects were analyzed by the Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test. The results were reported as the least square mean ± SEM, and a treatment difference was declared significant at P<0.05.

Results

Effects of leucine and phenylalanine on the gastrointestinal development in male calves

Table 3 shows the effect of the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk on the development of the gastrointestinal tract in male calves. Leucine and phenylalanine had no significant effect on the pre-slaughter weight, rumen and reticulum volume, omasum weight, abomasum weight, relative weight of each stomach compartment, and relative length of each intestine segment (P>0.05), and there was no interaction effect (P>0.05). Leucine supplementation significantly reduced the body length and the rumen and reticulum weight in calves (P<0.05). Compared with the control group, the leucine group had a 5.3% decrease in body length and a 6.7% decrease in the rumen and reticulum weight, whereas the phenylalanine group had a significant effect on body length (P<0.05) and a significant decreasing effect on the rumen and reticulum weight (P=0.093). Compared with the control group, the phenylalanine group had a 5.2% decrease in body length. Leucine and phenylalanine in combination had an interaction in impacting the body length (P<0.05).

Table 3.

Gastrointestinal development in male Holstein calves fed milk and a starter diet supplemented with leucine and phenylalanine

| Item | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | P | L | PL | P | L | P×L | ||

| Body weight (initial), kg | 40.5 | 41.8 | 39.8 | 42.1 | 0.56 | 0.137 | 0.863 | 0.653 |

| Body weight (final), kg | 79.2 | 79.1 | 78.5 | 75.5 | 0.03 | 0.329 | 0.180 | 0.334 |

| Body length, cm | 92.03 | 88.53 | 88.40 | 87.90 | 0.205 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Average daily gain, g | 788a | 763a | 791a | 683b | 10.8 | 0.006 | 0.086 | 0.071 |

| Rumen and reticulum weight, kg | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.013 | 0.093 | 0.025 | 0.652 |

| Rumen and reticulum volume, L | 9.62 | 9.49 | 8.72 | 9.28 | 0.320 | 0.686 | 0.297 | 0.522 |

| Omasum weight, kg | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.004 | 0.591 | 0.341 | 0.115 |

| Abomasum weight, kg | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.011 | 0.127 | 0.977 | 0.909 |

| Relative weight to final body weight, 100% | ||||||||

| Rumen and reticulum | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.015 | 0.318 | 0.101 | 0.365 |

| Omasum | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.005 | 0.954 | 0.277 | 0.268 |

| Abomasum | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.015 | 0.233 | 0.700 | 0.679 |

| Intestinal length/body length, cm/cm | ||||||||

| Duodenum | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.023 | 0.125 | 0.334 | 0.635 |

| Jejunum | 24.85 | 23.10 | 22.39 | 21.09 | 0.611 | 0.232 | 0.089 | 0.859 |

| Ileum | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.018 | 0.821 | 0.751 | 0.460 |

| Total small intestinal tract | 25.70 | 24.04 | 23.28 | 22.05 | 0.613 | 0.258 | 0.094 | 0.862 |

| Cecum | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.010 | 0.533 | 0.987 | 0.381 |

| Colon | 2.85 | 2.90 | 2.98 | 2.99 | 0.059 | 0.782 | 0.346 | 0.876 |

| Rectum | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.015 | 0.275 | 0.336 | 0.682 |

| Total large intestinal tract | 3.40 | 3.53 | 3.59 | 3.66 | 0.071 | 0.485 | 0.276 | 0.793 |

C, control; P, phenylalanine; L, leucine; PL, leucine plus phenylalanine.

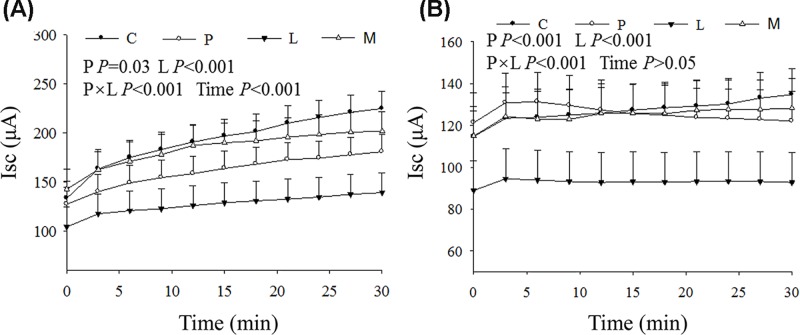

Figure 1 shows the effect of the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk on the Isc in the rumen and duodenum of male calves. Leucine and phenylalanine significantly affected Isc in the rumen and duodenum (P<0.01), and there was an interaction between the two (P<0.001). Compared with that in the control group, the Isc was decreased by 34.1% in the rumen and 26.9% in the duodenum in the leucine supplementation group. Although phenylalanine significantly affected the Isc in the rumen and duodenum (P<0.01), there was no significant difference in Isc between the phenylalanine group and the control group nor between the mixed amino acid group and the control group (P>0.05). Compared with the leucine group, the phenylalanine group had an Isc increase of 26.7% in the rumen and 35.6% in the duodenum.

Figure 1.

The diagram of the rumen and duodenum Isc

Changes of the Isc of rumen (A) and duodenum (B) in male Holstein calves fed milk and a starter supplemented with leucine and phenylalanine.

Effects of leucine and phenylalanine on the digestive enzyme activity in small intestinal chyme

Table 4 shows the effect of the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk on the lactase activity in the small intestinal chyme of male calves. The addition of leucine and phenylalanine did not affect the intestinal lactase activity (P>0.05). There was no significant difference in the lactase activity either at the same site between different treatments or between different sites for the same treatment (P>0.05).

Table 4.

Digestive lactase activity (U/mg protein) in male Holstein calves fed milk and a starter supplemented with leucine and phenylalanine

| Sampling Site (%) | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | P | L | PL | P | L | P × L | ||

| 0 | 357.26 | 400.36 | 290.15 | 425.42 | 54.289 | 0.425 | 0.849 | 0.678 |

| 20 | 343.13 | 282.20 | 520.50 | 669.35 | 72.513 | 0.766 | 0.692 | 0.480 |

| 40 | 452.93 | 354.98 | 448.43 | 565.68 | 52.261 | 0.936 | 0.399 | 0.379 |

| 60 | 503.54 | 637.13 | 521.53 | 440.03 | 83.298 | 0.878 | 0.599 | 0.529 |

| 80 | 301.83 | 412.11 | 633.86 | 368.19 | 58.658 | 0.519 | 0.240 | 0.131 |

| 100 | 589.58 | 339.46 | 458.28 | 397.50 | 62.978 | 0.235 | 0.775 | 0.463 |

| Site effect | P=0.728 | |||||||

| Interaction between Site and Treatment | P=0.604 | |||||||

C, control; P, phenylalanine; L, leucine; PL, leucine plus phenylalanine. The total length of the small intestine from the distal region of the pylorus to the ileal–cecal junction was defined as 100%. The digesta samples at the 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% relative sites were collected to determine enzyme activities.

Table 5 shows the effect of the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk on the α-amylase activity in the small intestinal chyme in male calves. Leucine and phenylalanine had no significant effect on the α-amylase activity (P>0.05). There was a significant difference in enzyme activities among various sites in the small intestine (P<0.05), and there was a trend toward an interaction between the treatment and the relative site of the small intestine (P=0.054). Except for the mixed amino acid group, the α-amylases activities in the small intestine in the other three groups showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing from the 0% site to the 100% site.

Table 5.

Digestive α-amylase activity (U/mg protein) in male Holstein calves fed milk and a starter supplemented with leucine and phenylalanine

| Sampling Site (%) | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | P | L | PL | P | L | P × L | ||

| 0 | 2.42b | 2.15bc | 2.47b | 3.53ab | 0.334 | 0.560 | 0.305 | 0.339 |

| 20 | 1.44b | 3.13bc | 1.64b | 2.02b | 0.313 | 0.477 | 0.117 | 0.312 |

| 40 | 1.44b | 1.03c | 1.39b | 2.03b | 0.236 | 0.815 | 0.331 | 0.279 |

| 60 | 3.57ab | 3.12bc | 4.11b | 1.90b | 0.655 | 0.327 | 0.800 | 0.515 |

| 80 | 4.52ab | 8.76b | 6.49a | 8.13a | 1.34 | 0.805 | 0.288 | 0.633 |

| 100 | 7.64a | 15.08a | 9.23a | 7.13a | 1.55 | 0.403 | 0.321 | 0.144 |

| Site effect | P<0.001 | |||||||

| Interaction between Site and Treatment | P=0.054 | |||||||

C, control; P, phenylalanine; L, leucine; PL, leucine plus phenylalanine. Different lowercase letters in a column indicate statistically significant differences (P<0.05). The total length of the small intestine from the distal region of the pylorus to the ileal-cecal junction was defined as 100%. The digesta samples at the 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% relative sites were collected to determine enzyme activities.

Table 6 shows the effect of the supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk on the trypsin activity in the small intestinal chyme of male calves. Leucine significantly increased the trypsin activity at the 20% site (P<0.05), and phenylalanine had no significant effect on the trypsin activity (P>0.05). There was no interaction between the two (P>0.05). The difference in the relative site significantly affected the trypsin activity (P<0.05).

Table 6.

Digestive trypsin activity (U/mg protein) in male Holstein calves fed milk and a starter supplemented with leucine and phenylalanine

| Sampling Site (%) | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | P | L | PL | P | L | P×L | ||

| 0 | 33.28a | 28.72 | 32.95 | 37.82 | 4.503 | 0.987 | 0.635 | 0.610 |

| 20 | 12.38b | 14.90 | 23.76 | 27.29 | 2.545 | 0.562 | 0.035 | 0.923 |

| 40 | 17.85b | 32.79 | 32.36 | 37.31 | 4.740 | 0.158 | 0.579 | 0.348 |

| 60 | 16.88b | 17.27 | 21.85 | 18.85 | 2.339 | 0.785 | 0.498 | 0.724 |

| 80 | 14.15b | 18.29 | 14.70 | 15.64 | 3.012 | 0.353 | 0.465 | 0.422 |

| 1002 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Site effect | P=0.008 | |||||||

| Interaction between Site and Treatment | P=0.891 | |||||||

C, control; P, phenylalanine; L, leucine; PL, leucine plus phenylalanine. Different lowercase letters in column indicte statistical significance (P<0.05). The total length of the small intestine from the distal region of the pylorus to the ileal-cecal junction was defined as 100%. The digesta samples at the 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% relative sites were collected to determine enzyme activities.

2not detected.

Discussion

The animal gastrointestinal tract is an important site for the communication of the internal and external environments, and its growth and development status would affect the absorption of nutrients by animals, thereby directly affecting the growth and performance of animals. Calves are in a critical period of growth and development and require a large amount of nutrients to meet the various needs of cell proliferation and differentiation, enzyme secretion, growth and development of tissues and organs, and synthesis of other important substances in the gastrointestinal tract. Dietary protein composition and protein intake would affect gastrointestinal development [23]. By increasing the raw milk intake in the first 23 days of lactation, the height and width of rumen papillae as well as the rumen and reticulum weight in 63-day-old calves are increased [6]. Leucine and phenylalanine are essential amino acids for calves, and they not only serve as substrates for protein synthesis but also play an important role in protein synthesis [14,24]. Studies on the effects of leucine and phenylalanine on gastrointestinal development and intestinal digestive enzyme activity in calves have rarely been reported. The regulation of leucine and phenylalanine on pancreatic exocrine has been reported [25,26]. Other amino acids such as isoleucine and glutamate also have effects on the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants. In Holstein heifers, for instance, duodenal isoleucine infusion increased the pancreatic exocrine function, especially α-amylase secretion, and the increment appeared to be dose and time dependent [27]. In cannulated steers, continuously duodenal infusion of casein and glutamate increased small intestinal starch digestion, but infusion of a mixture of phenylalanine, tryptophan and methionine did not affect the digestion of starch [28].

The results of this experiment showed that the addition of leucine and phenylalanine in raw milk reduced the absolute weight of the rumen in calves, but it had no significant effect on the relative weight of the rumen and on the rumen and reticulum volume. Although the rumen and reticulum weight can to some extent explain the development of the rumen and reticulum, the rumen and reticulum volume is more directly related to the feed intake at the late period from the perspective of its function. The rumen and reticulum weights were changed, but the volume did not change, indicating that the distribution of the added amino acids in various tissues of the body may differ.

Absorption of nutrients in the intestine mainly depends on the transport function of Na+-dependent transporters in the intestine, which can cause changes in the net ion transport in the intestinal tissues, thereby resulting in changes of the electrophysiological parameters in the intestinal tissues. The ion pump in the epithelial cell membrane produces Isc as the pump moves ions from one side of the membrane to the other. Researchers typically use Ussing Chamber technology to detect the physiologic electrical changes produced by ion transport in the plasma membrane, with the form of Isc used to express the absorption and transport capacity of a certain nutrient in the intestinal tissue. With the measurement and data output of Isc, trans-epithelial substance transport activities can be ascertained. Isc is an important indicator reflecting intestinal nutrient absorption, permeability, and ion secretion capacity. Isc can effectively reflect the integrity of the intestinal epithelial structure [29,30]. In this study, leucine supplementation could significantly reduce the Isc level in the rumen and duodenal mucosa; the leucine group had a significantly lower Isc level than the other three groups, indicating that the junction between the rumen and duodenal epithelial cells was tighter. Phenylalanine could inhibit the effect of leucine, and there was an interaction effect between the two. The use of the Ussing Chamber in goats to determine the effect of low-nitrogen and high-nitrogen diets on small intestinal Isc showed that the small intestinal electrophysiological Isc was significantly reduced with increasing CP levels in the diet [31,32]. The result of those studies are consistent with the results of this experiment, which showed that the addition of leucine and phenylalanine in calves significantly reduced Isc in the rumen and duodenum.

Small intestinal digestive enzymes play an important role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients. Digestive enzyme activity can to some extent explain the nutrient digestion ability in animals. Leucine and phenylalanine have the function of regulating the secretion of pancreatic juices and promoting the synthesis of pancreatic enzymes in ruminants [15,16,17]. Our previous studies in young dairy goats showed that the perfusion of leucine and phenylalanine significantly increased the amylase activity at the 0% site, perfusion of 9 g of leucine per day significantly increased the amylase activity at the 20% site, perfusion of 2 g of phenylalanine per day significantly increased the amylase activity at the 80% site, and perfusion of 9 g of leucine per day significantly increased the trypsin activity at the 0, 20, and 40% sites and the lipase activity at the 0 and 20% sites [16]. In this experiment, supplementation of leucine and phenylalanine did not affect the activities of lactase and amylase, and leucine administration significantly increased the trypsin activity at the 20% site. There was no significant difference in lactase activity across the various sites; the amylase activity in the small intestinal posterior segment was high, whereas the trypsin activity in the small intestinal anterior segment was high. This result is not fully consistent with the above test results, which is mainly due to the physiological differences in the digestive tract between young ruminants and adult ruminants. What’s more, the mechanism of leucine affects enzymes secretion is different from that by phenylalanine. In our recent studies, leucine regulated enzymes release through proteasome [33]. At the same time, amino acid supplementation only had a significant effect on the trypsin activity, which may be because trypsin is more sensitive to dietary changes [34]. The changes of amylase and lactase activity at different sites may be attributed to the conditions of the late stages of this experiment: the diet was still mainly raw milk and the feed intake of the starter diet was relatively little, thus resulting in a fast rate of chyme outflow during this period.

Conclusion

This study showed that leucine supplementation can promote the development of the gastrointestinal tract in calves and increase the activity of trypsin in the small intestine, whereas phenylalanine supplementation had a negative interaction with leucine and inhibits the effects of leucine in promoting the reduction of intestinal Isc.

Abbreviations

- C

control group

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CP

crude protein

- DM

dry matter

- L

leucine group

- OD

optical density

- p

phenaylalanine group

- PL

leucine + phenaylalanine

Competing Interests

All authors have confirmed that we do not have any actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within 3 years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, our work.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant numbers 2018YFD0501600]; and the Collaborative Innovation Major Project of Industry, University, Research, and Application in the Yangling Demonstration Zone [grant numbers 2016CXY-18].

Author Contribution

Y.C. and J.Y. conceived and designed the experiments; Y.C., X.Y., L.G., and C.C. performed the experiments; Y.C. and S.L. analyzed the data; S.L. and C.C. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Y.C., X.Y., and J.Y. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Bunting L.D., Tarifa T.A., Crochet B.T., Fernandez J.M., Depew C.L. and Lovejoy J.C. (2000) Effects of dietary inclusion of chromium propionate and calcium propionate on glucose disposal and gastrointestinal development in dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 83, 2491–2498 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75141-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehoe S.I., Heinrichs A.J., Lyons T.P. and Jacques K.A. (2004) Gastrointestinal development in dairy calves: Nutritional biotechnology in the feed and food industries[C]. Proceedings of Alltech's 20th Annual Symposium: Re-Imagining the Feed Industry, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A., 23–26 May 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosiorowska A., Puggaard L., Hedemann M.S., Sehested J., Jensen S.K., Kristensen N.B.. et al. (2011) Gastrointestinal development of dairy calves fed low- or high-starch concentrate at two milk allowances. Animal 5, 211–219 10.1017/S1751731110001710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Y.F., Wang Y.J., Zou Y., Azarfar A., Wei X.L., Ji S.K.. et al. (2017) Influence of dairy by-product waste milk on the microbiomes of different gastrointestinal tract components in pre-weaned dairy calves. Sci. Rep. 7, 42689 10.1038/srep42689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan M.A., Lee H.J., Lee W.S., Kim H.S., Ki K.S., Hur T.Y.. et al. (2007) Structural growth, rumen development, and metabolic and immune responses of Holstein male calves fed milk through step-down and conventional methods. J. Dairy Sci. 90, 3376–3387 10.3168/jds.2007-0104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu G.Y. (2013) Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids 45, 407–411 10.1007/s00726-013-1500-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boultwood J., Yip B.H., Vuppusetty C., Pellagatti A. and Wainscoat J.S. (2013) Activation of the mTOR pathway by the amino acid L-leucine in the 5q-syndrome and other ribosomopathies. Adv. Biol. Regul. 53, 8–17 10.1016/j.jbior.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J., Song G., Wu G.Y., Gao H.J., Johnson G.A. and Bazer F.W. (2013) Arginine, leucine, and glutamine stimulate proliferation of porcine trophectoderm cells through the MTOR-RPS6K-RPS6-EIF4EBP1 signal transduction pathway. Biol. Reprod. 88, 1–9 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S., Chu L., Qiao S., Mao X. and Zeng X. (2016) Effects of dietary leucine supplementation in low crude protein diets on performance, nitrogen balance, whole-body protein turnover, carcass characteristics and meat quality of finishing pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 87, 911–920 10.1111/asj.12520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Columbus D.A., Steinhoff J., Suryanwan A., Nguyen H.V., Hernandez-Garcia A., Fiorotto M.L.. et al. (2015) Impact of prolonged leucine supplementation on protein synthesis and lean growth in neonatal pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 309, E601–E610 10.1152/ajpendo.00089.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y., Wu Z., Li W., Zhang C., Sun K., Ji Y.. et al. (2015) Dietary l-leucine supplementation enhances intestinal development in suckling piglets. Amino Acids 47, 1517–1525 10.1007/s00726-015-1985-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankowska A., Laubitz D., Guillaume D., Kotunia A., Kapica A. and Zabielski R. (2007) The effect of pentaghrelin on amylase release from the rat and porcine dispersed pancreatic acinar cells in vitro. Livest. Sci. 108, 65–67 10.1016/j.livsci.2007.01.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crozier S.J., Sans M.D., Lang C.H., D'Alecy L.G., Ernst S.A. and Williams J.A. (2008) CCK-induced pancreatic growth is not limited by mitogenic capacity in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 294, G1148–G1157 10.1152/ajpgi.00426.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doepel L., Hewage I.I. and Lapierre H. (2016) Milk protein yield and mammary metabolism are affected by phenylalanine deficiency but not by threonine or tryptophan deficiency. J. Dairy Sci. 99, 3144–3156 10.3168/jds.2015-10320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Z.P., Xu M., Liu K., Yao J.H., Yu H.X. and Wang F. (2014) Leucine markedly regulates pancreatic exocrine secretion in goats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 98, 169–177 10.1111/jpn.12069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Z.P., Xu M., Wang F., Liu K., Yao J.H., Wu Z.. et al. (2014) Effect of duodenal infusion of leucine and phenylalanine on intestinal enzyme activities and starch digestibility in goats. Livest. Sci. 162, 134–140 10.1016/j.livsci.2014.01.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu K., Liu Y., Liu S.M., Xu M., Yu Z.P., Wang X.. et al. (2015) Relationships between leucine and the pancreatic exocrine function for improving starch digestibility in ruminants. J. Dairy Sci. 98, 2576–2582 10.3168/jds.2014-8404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abe M., Iriki T., Kondoh K. and Shibui H. (1979) Effects of nipple or bucket feeding of milk-substitute on rumen by-pass and on rate of passage in calves. Br. J. Nutr. 41, 175–181 10.1079/BJN19790024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AOAC. (1999) Official Methods of Analysis, 16th edn, Association of Analytical Chemists, Washington, DC, U.S.A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Soest P.J., Robertson J.B. and Lewis B.A. (1991) Symposium: carbohydrate methodology, metabolism, and nutritional implications in dairy cattle, methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74, 3583–3597 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roseiro L.C., Santos C., Sol M., Borges M.J., Anjos M., Gonçalves H.. et al. (2008) Proteolysis in Painho de Portalegre dry fermented sausage in relation to ripening time and salt content. Meat Sci. 79, 784–794 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X.F., Li Y.L., Yang X.J. and Yao J.H. (2013) Astragalus polysaccharide reduces inflammatory response by decreasing permeability of LPS-infected Caco2 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 61, 347–352 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh H.K., Kim J.D., Lee J.H. and Han I.K. (2000) Effects of protein levels on the development of the gastrointestinal tract in pigs weaned at 21 days of age. Technometrics 20, 215–217 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appuhamy J.A.D.R., Knoebel N.A., Nayananjalie W.A.D., Escobar J. and Hanigan M.D. (2012) Isoleucine and leucine independently regulate mTOR signaling and protein synthesis in MAC-T cells and bovine mammary tissue slices. J. Nutr. 142, 484–491 10.3945/jn.111.152595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo L., Tian H., Shen J., Zheng C., Liu S., Cao Y.. et al. (2018) Phenylalanine regulates initiation of digestive enzyme mRNA translation in pancreatic acinar cells and tissue segments in dairy calves. Bioscience Rep. 38, BSR20171189 10.1042/BSR20171189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo L., Liang Z., Zheng C., Liu B., Yin Q., Cao Y.. et al. (2018) Leucine affects α-amylase synthesis through PI3K/Akt-mTOR signaling pathways in pancreatic acinar cells of dairy calves. J. Agr. Food. Chem. 66, 5149–5156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu K., Shen J., Cao Y., Cai C. and Yao J. (2017) Duodenal infusions of isoleucine influence pancreatic exocrine function in dairy heifers. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 72, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brake D.W., Titgemeyer E.C. and Anderson D.E. (2014) Duodenal supply of glutamate and casein both improve intestinal starch igestion in cattle but by apparently different mechanisms. J. Anim. Sci. 92, 4057–4067 10.2527/jas.2014-7909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarkel L.L. (2009) A guide to Ussing chamber studies of mouse intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296, G1151–G1166 10.1152/ajpgi.90649.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y.F., Weisbrodt N.W., Harariy Y. and Moody F.G. (1991) Use of a modified Ussing chamber to monitor intestinal epithelial and smooth muscle functions. Am. J. Physiol. 261, 166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muscher A.S., Wilkens M.R., Mrochen N., Schroder B., Breves G. and Huber K. (2012) Ex vivo intestinal studies on calcium and phosphate transport in growing goats fed a reduced nitrogen diet. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 628–637 10.1017/S0007114511005976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muscherbanse A.S., Piechotta M., Schr Der B. and Breves G. (2012) Modulation of intestinal glucose transport in response to reduced nitrogen supply in young goats. J. Anim. Sci. 90, 4995–5004 10.2527/jas.2012-5143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo L., Liu B., Zheng C., Bai H., Ren H., Yao J.. et al. (2018) Inhibitory effect of high leucine concentration on amylase secretion by pancreatic acinar cells: possible key factor of proteasome. Bioscience Rep. 38, 10.1042/BSR20181455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huerou-Luron I.L., Guilloteau P., Pierzynowski S.G. and Zabielski R. (1999) Effects of age and food on exocrine pancreatic function and some regulatory aspects: a review. Developments in Animal and Veterinary Sciences (Netherlands) 28, 213–229 [Google Scholar]