Abstract

RNA can anneal to its DNA template to generate an RNA-DNA hybrid (RDH) duplex and a displaced DNA strand, termed R-loop. RDH duplex occupies up to 5% of the mammalian genome and plays important roles in many biological processes. The functions of RDH duplex are affected by its mechanical properties, including the elasticity and the conformation transitions. The mechanical properties of RDH duplex, however, are still unclear. In this work, we studied the mechanical properties of RDH duplex using magnetic tweezers in comparison with those of DNA and RNA duplexes with the same sequences. We report that the contour length of RDH duplex is ∼0.30 nm/bp, and the stretching modulus of RDH duplex is ∼660 pN, neither of which is sensitive to NaCl concentration. The persistence length of RDH duplex depends on NaCl concentration, decreasing from ∼63 nm at 1 mM NaCl to ∼49 nm at 500 mM NaCl. Under high tension of ∼60 pN, the end-opened RDH duplex undergoes two distinct overstretching transitions; at high salt in which the basepairs are stable, it undergoes the nonhysteretic transition, leading to a basepaired elongated structure, whereas at low salt, it undergoes a hysteretic peeling transition, leading to the single-stranded DNA strand under force and the single-stranded RNA strand coils. The peeled RDH is difficult to reanneal back to the duplex conformation, which may be due to the secondary structures formed in the coiled single-stranded RNA strand. These results help us understand the full picture of the structures and mechanical properties of nucleic acid duplexes in solution and provide a baseline for studying the interaction of RDH with proteins at the single-molecule level.

Introduction

Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) can anneal to its double-stranded DNA template co-transcriptionally or post-transcriptionally to generate an RNA-DNA hybrid (RDH) duplex and a displaced single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), which is termed an R-loop. Around 59% of human genes contain RDH-forming sequences (1). The RDH duplex occupies up to 5% of the mammalian genome (2) and 8% of the budding yeast genome (3). The RDH duplex causes DNA damage and genome instability, although it also plays positive roles in many biological processes such as transcription regulation, replication regulation, genome modulation, chromosome segregation, telomere regulation, DNA methylation, and DNA repair (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). The RDH duplex is related to human diseases, including certain cancers and a considerable number of neurological disorders (15, 16, 17, 18, 19). In addition, the RDH duplex is also involved in many applications, such as gene editing (20), nanotechnology (21), and disease treatment (22).

The biophysical properties of the RDH duplex have been studied in various aspects. The RDH duplex adopts a conformation that is an intermediate between the A-form RNA and B-form DNA (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29). The thermal stabilities of the DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes are RNA > RDH > DNA (or RNA > DNA > RDH for sequences in which the RDH duplex contains high purine content in its DNA strand) (30, 31, 32, 33). The biological functions of nucleic acid duplexes are related to the mechanical properties, including the elasticity and the conformational transitions. Thus, the mechanical properties of DNA and RNA duplexes have been studied excessively using single-molecule manipulation techniques (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46). The elasticity of both DNA and RNA duplexes can be described using an extensible worm-like chain (WLC) model at the elastic region before overstretching (47). Under high tension of ∼60 pN, both DNA and RNA duplexes undergo the overstretching transition, which elongates the extension by ∼1.7-fold in a narrow force range (38). In single-molecule manipulation experiments studying RNA structures such as hairpins, pseudoknots, and riboswitch aptamers, RDH duplexes are often used as handles (48, 49, 50, 51, 52). Despite the biophysical importance of the mechanical properties of the RDH duplex, precise experimental measurements of the mechanical properties of the long RDH duplex are still lacking.

In this work, we will characterize the elasticity and the conformational transitions of the RDH duplex stretched by single-molecule MT in comparison with those of DNA and RNA duplexes. Our aim is to provide a better understanding of the structures and mechanical properties of the three types of native nucleic acid duplexes (i.e., DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes) in solution.

Materials and Methods

MT

The homebuilt transverse and vertical magnetic tweezers (MT) were used in this work. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, a single DNA, RDH, or RNA duplex molecule was anchored between an anti-digoxigenin (dig)-coated glass slide and a streptavidin-coated superparamagnetic microbead. A pair of closed (for transverse MT) or separated (for vertical MT) NdFeB magnets was used to attract the bead and exert a constant tensile force to the anchored molecule. The closed magnets of transverse MT can exert larger forces than the separated magnets of vertical MT. The applied force was controlled by the position of the magnets, and the value of the applied force was calculated based on the Brownian motion of the bead (53). The extension of the tethered molecule was determined to be the distance between the bead and glass surfaces. For the transverse MT, the temperature inside the flow cell was maintained at a constant temperature using a homebuilt Peltier temperature controller (54).

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. (A) Transverse MT with temperature control for overstretching measurements. (B) Vertical MT for force-extension response measurements. (C) Five DNA, RDH, and RNA constructs. (i–iii) DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes containing the same 12.5-kbp sequences for force-extension response measurements. (iv–v) DNA and RDH duplexes containing the same 13.6-kbp sequences for overstretching experiments. To see this figure in color, go online.

In experiments using vertical MT, we applied Dynabeads MyOne (1 μm in diameter) in the force range of 0.1–3 pN and Dynabeads M-270 (2.8 μm in diameter) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for forces in the range of 2–30 pN. We did not use higher forces because forces higher than 30 pN can break the single anti-dig-dig bond. To minimize the error in extension caused by bead distortion in the force-extension response measurements, we chose those molecules anchored near the right bottom of the beads. We rotated the attached bead to determine the off-center radius and chose those beads with off-center radius <200 nm for M-270 beads and <120 nm for MyOne beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in which the error in extension was <15 nm (55, 56). (Fig. S1). We determined the offset of the extension of the tethered molecule by the height of the tracked bead in contact with the glass slide surface at zero force (55).

To avoid the interaction between the tethered molecule and glass or bead surfaces, we passivated the surfaces with 10% w/v methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-Succinimidyl Valerate (MW 2K; Laysan Bio, Arab, AL) in 100 mM diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated sodium bicarbonate solution. To minimalize the contribution of ionization of Tris-HCl to the total salt concentration, a low concentration of 1 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) was used. The buffers containing 1-1000 mM NaCl were prepared by mixing RNase-free stock solutions and diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To avoid water evaporation during hours of measurement at each NaCl concentration, we sealed the flow cell with Vaseline during force-extension response measurements.

DNA, RDH, and RNA constructs

As shown in Fig. 1 C, we constructed five different DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes. We labeled each duplex with dig and biotin groups at its two ends, respectively. The strands on which the dig or biotin groups were attached in each duplex are indicated in the figure. The DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes (Fig. 1 C (i)–(iii)) with two open ends with the same 12.5-kbp sequences (43.9% GC, 48.7% purine in the DNA strand of RDH duplex) for the force-extension response measurements with vertical MT shown in Figs. 2 and 3. To obtain the exact extension per basepair of the DNA/RDH/RNA duplex, we labeled the two ends of each duplex at the terminal, and the whole molecule was under tension when stretched by MT. Although the dig-anti-dig bond is weaker than the biotin-avidin bond, the single dig-anti-dig bond enables us to stretch the molecule up to 30 pN for hours, during which the force-extension responses were measured, and the elastic parameters were calculated. We did not use covalent bonds (such as the thiol-maleimide bond and the azide-allylene bond) to replace the weaker dig-anti-dig bond because the covalent bonds need a long period of time to form and passivate, during which nicks may form. Note that there is a nick near the terminal of each end of the RNA duplex.

Figure 2.

The force-extension responses of DNA (top curves), RDH (middle curves), and RNA (bottom curves) duplexes at 1 (A), 10 (B), 100 (C), and 500 (D) mM NaCl at 22°C and pH 7.5. For each NaCl concentration and each type of duplex, data from independent molecules are indicated by different symbols (N > 5). They are plotted together and fitted to the extensible WLC model (black lines). We did not measure the force-extension response of the RNA duplex at 1 mM NaCl because the RNA tether would break from the nicks near the ends because of the low basepair stabilities at low salt. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

Fitting parameters with extensible WLC model (Eq. 1) for DNA (circles), RDH (triangles), and RNA (squares) duplexes at 22°C as functions of NaCl concentration. The average and SD in the fitting parameters obtained using different molecules (N > 5) were plotted as data points and error bars. (A) The persistence length is P. (B) The stretching modulus is K. (C) The contour length is Lc. To see this figure in color, go online.

The DNA and RDH duplexes with the same 13.6-kbp sequences (Fig. 1 C (iv)–(v)) (43.3% GC, 48.6% purine in the DNA strand of RDH duplex) for overstretching experiments with transverse MT are shown in Figs. 4 and 6. For each duplex used for overstretching, the same DNA strand in the duplex was labeled with dig at its 5′ end and labeled with biotin at its 3′ end. The duplex was labeled with multiple (∼5) dig groups at the 519 basepairs near the terminal for bearing high tension in overstretching experiments (57). We were not sure which ones of the 519 basepairs were attached to the glass surface; thus, there was some uncertainty in the stretched sequence length (13.1–13.6 kbp) when the duplex was stretched by MT. In practical terms, we use 13.4 kbp for calculation. Because a few hundred basepairs near the terminal were free of tension, peeling was unlikely to occur from the multiple-dig-labeled end (58) (Fig. S2). The other end of each duplex was labeled with a biotin group at the terminal, and peeling may occur at this end. Please refer to Fig. S3 for details of the preparation of DNA, RDH, and RNA constructs.

Figure 4.

The nonhysteretic overstretching transition for DNA (squares) and RDH (triangles) duplexes with the same sequences. The onset and completion of the transition were indicated by arrows. (A) Nonhysteretic overstretching transition is represented by force-extension curves obtained through a stretching process (filled symbols), followed by a relaxing process (empty symbols). Each constant force was kept for 2 s, during which the average in extension was calculated and plotted as a data point. The stiffness of the S-form DNA and RDH duplexes were obtained by fitting their force-extension responses to linear functions (black lines). (B) The variance in extension as a function of force during the nonhysteretic overstretching transition for DNA and RDH duplexes. Each constant force was kept for 10 s, during which the variance in extension was calculated and plotted as a data point. The values of force and variance in extension at the onset and completion of transition were indicated in the figure. (C) Nonhysteretic transitions for DNA and RDH duplexes were demonstrated by the extension relative to the contour length as functions of force. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

Single-molecule calorimetry measurements to determine the entropy changes during the nonhysteretic overstretching transition for DNA (filled squares) and RDH (filled triangles) at 1 M NaCl and pH 7.5. The hysteretic peeling transitions are shown in empty symbols. We did not plot error bars in three repeating measurements because they were smaller than the size of symbols. To see this figure in color, go online.

Results

The elasticity of the RDH duplex at various NaCl concentrations

We studied the elasticity of RDH by measurements of the force-extension responses using vertical MT and compared it to the elasticity of DNA and RNA with the same sequences. As shown in Fig. 2, we measured the force-extension responses of DNA (orange), RDH (olive), and RNA (magenta) duplexes at various NaCl concentrations at 22°C in the force range of 0.1–30 pN. We fitted our experimental data to the extensible WLC model (47):

| (1) |

Here, the two variables are L (the measured extension) and F (the applied tensile force). The three parameters are Lc (the contour length), P (the persistence length), and K (the stretching modulus). The average fitting curves at the same salt conditions for the DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes are shown in Fig. 2 (black lines), and the fitting parameters as functions of NaCl concentration are shown in Fig. 3.

The elastic parameters of the RDH duplex are in between those of the DNA and RNA duplexes (Fig. 3). The persistence length of the RDH duplex, which decreases from ∼63 nm at 1 mM NaCl to ∼49 nm at 500 mM NaCl (Fig. 3 A), sensitively depends on NaCl concentration. The persistence length of RDH is in between that of the persistence length of DNA and RNA at the same NaCl concentration. The contour length and stretching modulus of the RDH duplex are not sensitive to NaCl concentration. The contour length (Fig. 3 C) of the RDH duplex (∼0.30 nm/bp) is in between that of the DNA (∼0.34 nm/bp) and RNA duplexes (∼0.28 nm/bp) but closer to that of the RNA duplex. The stretching modulus (Fig. 3 B) of the RDH duplex (∼660 pN) is slightly larger than that of the RNA duplex (∼630 pN) but only about half of that of the DNA duplex (∼1300 pN). We found the RNA tether containing two nicks near its terminals often broke at the low salt of 1 mM NaCl. Thus, we did not measure the elasticity of RNA duplex at 1 mM NaCl.

The nonhysteretic overstretching transition of RDH duplex and the elongated S-RDH conformation

B-DNA undergoes a nonhysteretic overstretching transition to an elongated basepaired conformation (i.e., S-DNA) under high tension at conditions in which the basepairs are stable, such as high salt concentrations, low temperature, and high GC DNA sequences (59, 60, 61, 62). To determine whether an elongated basepaired S-form RDH also exists, we stretched the RDH duplex and compared it with the DNA duplex using high tension at high basepair stabilities. For reference, we first studied the nonhysteretic overstretching transition (i.e., B-to-S transition) of the DNA duplex with one open end at a high salt concentration of 1 M NaCl and a low temperature of 10°C in which the basepair stabilities were high. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the measurements were performed by a stretching process during which the force was kept at a series of increasing constant forces (filled magenta triangles), followed by a relaxing process during which the force was kept at the reverse series of decreasing constant forces (empty magenta triangles). During each constant force of 2 s, the average in extension was plotted as a function of force. As shown in Fig. 4 A, the DNA duplex elongated to ∼1.7-fold of its contour length in a narrow force range near 65 pN, which was called DNA overstretching. The relaxing force-extension curve (magenta empty triangles) overlapped the stretching force-extension curve (magenta filled triangles), which demonstrated that the structural transition was a nonhysteretic transition leading to the formation of the elongated basepaired S-DNA (34, 59, 60, 63, 64, 65). Compared with force-extension curves, the force-variance curves are more sensitive to detect the onset and completion of DNA overstretching (54, 60). As shown in Fig. 4 B, the onset of overstretching transition was determined to be the force at which the variance in extension increased abruptly, and the completion of overstretching transition was determined to be the force at which the variance in extension decreased back to a roughly constant value. The nonhysteretic B-to-S transition of the DNA duplex occurred in a force range between ∼65 and ∼71 pN, indicated by the variance in extension (magenta, Fig. 4 B), during which the extension of the DNA duplex increased from ∼0.35 to ∼0.57 nm/bp.

The overstretching transition of the RDH duplex was also studied using a similar stretch-relax procedure at 1 M NaCl and 10°C in which basepairs were stable (olive, Fig. 4 A). We found the RDH duplex also underwent a nonhysteretic transition indicated by overlapping stretching force-extension curve (filled olive squares) and relaxing force-extension curve (empty olive squares). The nonhysteretic transition of the RDH duplex occurred in a wider force range between ∼57 and ∼72 pN, indicated by the variance in extension (olive, Fig. 4 B), during which the extension of RDH duplex increased from ∼0.33 to ∼0.48 nm/bp. Here, we term the elongated RDH conformation generated in the nonhysteretic overstretching transition as S-RDH. We fitted the force-extension curves of S-RDH and S-DNA to linear functions (black lines, Fig. 4 A). The stiffness of S-RDH was determined to be 0.4 N/(m/bp), which was much smaller than the stiffness of S-DNA (2.3 N/(m/bp)). Extension relative to the contour length during the nonhysteretic overstretching transitions for the DNA (magenta triangles) and RDH (olive squares) duplexes were also plotted together in Fig. 4 C for comparison.

The hysteretic peeling transition of RDH and the difficulty for peeled RDH to reanneal

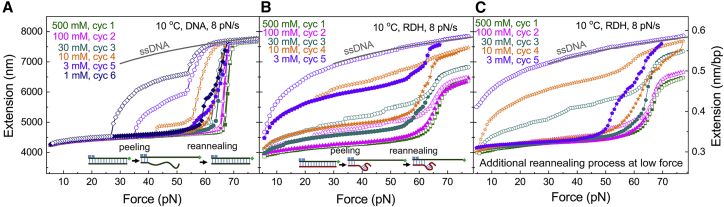

B-DNA with nicks or open ends undergoes the hysteretic peeling transition to an ssDNA under tension, whereas the other ssDNA strands coils at conditions in which the basepairs are less stable (e.g., at low salt) (59, 60, 61, 62). As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, we studied the overstretching of the RDH duplex and compared it with that of the DNA duplex with the same sequences at various NaCl concentrations at 10°C. After measurements of the force-extension curves through a stretching-relaxing cycle at higher NaCl concentration, we immediately changed to a lower NaCl concentration and performed the stretching-relaxing cycle at the lower salt. We found the nonhysteretic overstretching transition occurred at 500 and 100 mM NaCl for the DNA duplex (olive and magenta in Fig. 5 A), whereas it occurred at 500 mM NaCl for the RDH duplex (olive in Fig. 5 B), indicated by overlapping stretching and relaxing force-extension curves. After the transition, the extension of the overstretched conformation approach the extension of S-DNA and S-RDH obtained in Fig. 4 A. Decreasing the NaCl concentration to reduce basepair stability caused a switch from the nonhysteretic transition to the hysteretic transition. When the concentration of NaCl was decreased to 1 mM for DNA and 3 mM for RDH, the extension of the DNA after the hysteretic transition approached that predicted for ssDNA (66) (gray lines), which is in agreement with the picture that only an ssDNA strand exists under tension, whereas the other ssDNA/ssRNA strand coils after peeling. In the middle NaCl concentrations (100, 30, 10, and 3 mM for DNA but 30 and 10 mM for RDH), the extension after overstretching was in between that of ssDNA and S-DNA/S-RDH, demonstrating the coexistence of both overstretched structures.

Figure 5.

Distinct overstretching transitions demonstrated by force-extension curves for the end-opened DNA (A) and RDH (B and C) duplexes at various NaCl concentrations at 10°C. At each buffer condition, the force-extension curves were measured in a stretch-relax cycle containing a stretching process (filled symbols), followed by a relaxing process (empty symbols). For (A) and (B), after the stretch-relax cycle at a higher NaCl concentration, we immediately changed to a lower NaCl concentration. For (C), after the stretch-relax cycle at a higher NaCl concentration, we kept the molecule at a low force of 1 pN for tens of seconds to speed up the reannealing (Fig. S4, G and H). After the molecule was fully reannealed, we changed to a lower NaCl concentration. To see this figure in color, go online.

We noted that the peeled DNA fully reannealed in the relaxing process indicated by the full recovery of the extension (Fig. 5 A), whereas the peeled RDH did not fully reanneal (Fig. 5 B). Two possible mechanisms may explain the difficulty for peeled RDH to reanneal: 1) reannealing to duplex may be hindered by secondary structures formed in the coiled ssRNA strand; and 2) if a larger number of nicks exist in the ssRNA strand of the RDH duplex, those ssRNA fragments in between covalent discontinuities (i.e., nicks and the open end) may completely dissociate during peeling transition, and thus the reannealing cannot occur. To address this question, we studied the overstretching of the RDH duplex at various NaCl concentrations at 10°C with an additional reannealing process at low force (Fig. 5 C). After the stretch-relax cycle at a higher NaCl concentration, we kept the molecule at a low force of 1 pN for tens of seconds to see whether the reannealing would occur eventually (Fig. S4, G and H). We found the peeled RDH fully annealed during the additional reannealing process, which infers that the difficulty for peeled RDH to reanneal is mainly caused by secondary structures formed in the coiled ssRNA strand. More force-extension curves demonstrating the overstretching transitions of end-opened DNA and RDH at various temperatures were shown in Fig. S4, A–F.

Single-molecule calorimetry measurements reveal S-RDH is a basepaired conformation

If S-RDH is a melted conformation without basepairing, we expect to see a large increase in entropy for the nonhysteretic transition of RDH duplex because the bases in the melted RDH conformation are rotational free. The entropy change during overstretching can be determined by measurements of transition force as a function of temperature using the following equation (54, 60, 67, 68):

| (2) |

Here, ΔS is the entropy change during the overstretching transition, Fov is the overstretching force, T is the temperature, and Δb is the extension change during the overstretching transition. In previous studies, we determined the entropy change to be ∼21.2 cal/(K ⋅ mol) during the hysteretic peeling transition and ∼−3.8 cal/(K ⋅ mol) during the nonhysteretic B-to-S transition in 150 mM NaCl for the end-opened DNA (54). The entropy change during DNA peeling is similar to the value of ∼24.2 cal/(K ⋅ mol) determined in the thermally induced melting (69), whereas the entropy change during the B-to-S transition is much smaller. Thus, S-DNA is determined to be a basepaired conformation.

As shown in Fig. 6, we measured the overstretching force as functions of temperature for both DNA and RDH duplexes at 1 M NaCl. The end-opened RDH duplex undergoes two types of overstretching transitions, the nonhysteretic S-RDH formation and the hysteretic peeling transition. To avoid co-occurrence of both types of overstretching transitions, we determined the overstretching force near the onset of the transition in which only one type of transition may occur (54). If we determine the right onset of overstretching in which the variance in extension increased abruptly, we need to measure the variance covering a large range of force, which is very time consuming. For convenience, we determined the overstretching force in which the variance in extension exceeded a threshold of 300 nm2 that was near the onset of transition. The DNA duplex underwent the nonhysteretic transition at 5–20°C (filled olive squares), whereas the RDH duplex underwent the nonhysteretic transition at 5–16°C (filled magenta triangles). The transition force was fitted to linear functions of temperature (olive and magenta lines), which yielded dFov/dT to be 0.12 pN/K for DNA and 0.23 pN/K for RDH. Considering the extension changes during the nonhysteretic overstretching transitions Δb of ∼0.22 nm/bp for DNA and ∼0.15 nm/bp for RDH (Fig. 4 A), the entropy changes during the nonhysteretic overstretching transition were determined to be ∼−3.8 cal/(K ⋅ mol) for DNA and ∼−4.9 cal/(K ⋅ mol) for RDH using Eq. 2. The negative entropy change during formation of S-RDH suggests that S-RDH is a basepaired conformation in which bases are not rotational free.

Discussion

In this work, we measured the elasticity of the RDH duplex from 0.1 to 30 pN and compared it with the elasticity of the DNA and RNA duplexes at various NaCl concentrations. The persistence length, stretching modulus, and contour length we determined for DNA and RNA duplexes are consistent with previous elastic results in various salt concentrations obtained by single-molecule experiments (36, 38) (45, 46). In this work, we found the elasticity of RDH duplex could also be described by the extensive WLC model (47). The persistence length and contour length of RDH are in between those of the DNA and RNA duplexes, whereas the stretching modulus of the RDH duplex is slightly larger than that of the RNA duplex. These results confirm that the RDH duplex adopts a conformation in between the B-form DNA and the A-form RNA but generally closer to the A-form RNA (24).

Under high tension of ∼60 pN, the end-opened RDH duplex undergoes two distinct overstretching transitions. At solution conditions in which the basepairs are more stable (e.g., high salt and low temperature), it undergoes the nonhysteretic transition with a negative entropy change of ∼−4.9 cal/(K ⋅ mol), which demonstrates the S-RDH is a basepaired conformation. During the nonhysteretic transition at 1 M NaCl and 10°C, the DNA duplex elongates from ∼0.35 to ∼0.57 nm/bp at ∼65 to ∼71 pN, whereas the RDH duplex only elongates from ∼0.33 to ∼0.48 nm/bp in a wider force range of ∼57 to ∼72 pN, which demonstrates that the formation of S-form is less cooperative for the RDH duplex than for the DNA duplex. Although the stretch modulus of the RDH duplex is ∼2-fold lower than the DNA duplex in the elastic regime, it is ∼6-fold lower in the S-form regime (Fig. 4 A). Because a weaker basestacking corresponds to a smaller stretch modulus, we think S-RDH is even less basestacked compared with S-DNA (38). Deep understanding of the properties of the S-form conformation may be achieved by future in silico studies using our results as experimental references. Previous single-molecule studies revealed that bubbling rather than peeling or B-to-S transition occurred for a synthetic 70% AT DNA core sandwiched by GC-rich end-opened handles (70). Previous results also revealed that a small number of small DNA bubbles made no detectable contribution to the hysteresis during DNA overstretching (59, 70). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that a small number of small bubbles formed at the AT-rich core during the nonhysteretic overstretching transitions in our measurements, which made no detectable contribution to the hysteresis and entropy change.

At the solution condition in which basepairs are less stable (e.g., low salt and high temperature), the RDH duplex undergoes a hysteretic peeling transition, leading to the ssDNA strand under force, whereas the ssRNA strand coils. Interestingly, the peeled DNA can fully reanneal to the duplex, whereas the peeled RDH is difficult to reanneal. We think the reannealing of peeled RDH is hindered by secondary structures formed in the coiled ssRNA strand. It is consistent with the previous results that the hysteresis during RNA overstretching increased with salt concentration because the RNA secondary structures are more stable at higher salt (38). This difficulty may partially explain the puzzle that 59% of human genes contain RDH-forming sequences (1) but much less RDH formed (2).

Several factors may affect the scale of hysteresis between the stretching and relaxing force-extension curves during overstretching of DNA, RDH, and RNA duplexes: 1) factors that affect basepair stabilities. Because both the nonhysteretic S-form formation and the hysteretic melting may occur during overstretching, a larger scale of hysteresis is expected at lower basepair stabilities in which a larger part of the duplex undergoes the hysteretic melting transition. As shown in Fig. 5 and Fig. S4, A–D, the hysteresis during overstretching of end-opened DNA and RDH duplexes are larger at lower salt concentrations and higher temperatures. Previous results for the DNA duplex also showed a larger hysteresis during DNA overstretching at lower salt, higher temperature, and lower GC content (34, 35, 45, 46, 54, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 68). Because the basepair stabilities of the RNA duplex are higher than the DNA duplex (30, 31, 32, 33), previous results also showed less hysteresis for RNA overstretching compared to DNA overstretching at the same buffer conditions (39); 2) the kinetics of the hysteretic transition. Because of the difficulty for peeled RDH to reanneal, the hysteresis during peeling transition is larger for the RDH duplex than for the DNA duplex with the similar scale of melting; 3) other factors such as pulling rate, temperature, double-strand, or single-stranded binding partners may also contribute to the scale of hysteresis between the stretching and relaxing force-extension curves during overstretching.

In this study, all the measurements were performed using duplexes with even GC and purine content without modifications. Previous single-molecule studies have revealed GC content and methylation on cytosines followed by guanine residues (CpG) methylation affected the elasticity of DNA (71, 72) and the conformation and thermal stability of the RDH duplex depended on the purine content of its DNA strand (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33). Thus GC content, purine content, and modifications may also affect the mechanical properties of the RDH duplex, which will be studied in the future.

These results help us understand the full picture of the helical structure and the mechanical properties of the three native nucleic acid duplexes in solution. These results also provide an experimental reference for in silico studies and provide a baseline to study the biological functions of RDH at the single-molecule level in the future.

Author Contributions

X.Z. designed the research. C.Z., H.F., and Y.Y. performed the experiment. H.F. and X.Z. analyzed data. C.Z., H.F., H.Y, Z.T., and X.Z. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (11704286, 31670760, and 21708009).

Editor: Gijs Wuite.

Footnotes

Chen Zhang, Hang Fu, and Yajun Yang contributed equally to this work.

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)34472-2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Wongsurawat T., Jenjaroenpun P., Kuznetsov V. Quantitative model of R-loop forming structures reveals a novel level of RNA-DNA interactome complexity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanz L.A., Hartono S.R., Chédin F. Prevalent, dynamic, and conserved R-Loop structures associate with specific epigenomic signatures in mammals. Mol. Cell. 2016;63:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahba L., Costantino L., Koshland D. S1-DRIP-seq identifies high expression and polyA tracts as major contributors to R-loop formation. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1327–1338. doi: 10.1101/gad.280834.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plosky B.S. The good and bad of RNA:DNA hybrids in double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. 2016;64:643–644. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costantino L., Koshland D. The Yin and Yang of R-loop biology. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;34:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos-Pereira J.M., Aguilera A. R loops: new modulators of genome dynamics and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015;16:583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrg3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguilera A., García-Muse T. R loops: from transcription byproducts to threats to genome stability. Mol. Cell. 2012;46:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamperl S., Cimprich K.A. The contribution of co-transcriptional RNA:DNA hybrid structures to DNA damage and genome instability. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2014;19:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu W.T., Hawley B.R., Bushell M. Drosha drives the formation of DNA:RNA hybrids around DNA break sites to facilitate DNA repair. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:532. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02893-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunseich C., Wang I.X., Cheung V.G. Senataxin mutation reveals how R-Loops promote transcription by blocking DNA methylation at gene promoters. Mol. Cell. 2018;69:426–437.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohle C., Tesorero R., Fischer T. Transient RNA-DNA hybrids are required for efficient double-strand break repair. Cell. 2016;167:1001–1013.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen P.B., Chen H.V., Fazzio T.G. R loops regulate promoter-proximal chromatin architecture and cellular differentiation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:999–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toubiana S., Selig S. DNA:RNA hybrids at telomeres - when it is better to be out of the (R) loop. FEBS J. 2018;285:2552–2566. doi: 10.1111/febs.14464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazzio T.G. Regulation of chromatin structure and cell fate by R-loops. Transcription. 2016;7:121–126. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2016.1198298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groh M., Gromak N. Out of balance: R-loops in human disease. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haeusler A.R., Donnelly C.J., Rothstein J.D. The expanding biology of the C9orf72 nucleotide repeat expansion in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016;17:383–395. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M.H., Pearson C.E. Disease-associated repeat instability and mismatch repair. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2016;38:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richard P., Manley J.L. R loops and links to human disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:3168–3180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perego M.G.L., Taiana M., Corti S. R-Loops in motor neuron diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1246-y. Published online July 25, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright A.V., Nuñez J.K., Doudna J.A. Biology and applications of CRISPR systems: harnessing nature’s toolbox for genome engineering. Cell. 2016;164:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko S.H., Su M., Mao C. Synergistic self-assembly of RNA and DNA molecules. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:1050–1055. doi: 10.1038/nchem.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen H.L., Reesink H.W., Hodges M.R. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1685–1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hantz E., Larue V., Huynh Dinh T. Solution conformation of an RNA--DNA hybrid duplex containing a pyrimidine RNA strand and a purine DNA strand. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2001;28:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(01)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noy A., Pérez A., Orozco M. Structure, recognition properties, and flexibility of the DNA.RNA hybrid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4910–4920. doi: 10.1021/ja043293v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyi J.I., Conn G.L., Brown T. Comparison of the thermodynamic stabilities and solution conformations of DNA.RNA hybrids containing purine-rich and pyrimidine-rich strands with DNA and RNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12538–12548. doi: 10.1021/bi960948z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gyi J.I., Lane A.N., Brown T. Solution structures of DNA.RNA hybrids with purine-rich and pyrimidine-rich strands: comparison with the homologous DNA and RNA duplexes. Biochemistry. 1998;37:73–80. doi: 10.1021/bi9719713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane A.N., Ebel S., Brown T. NMR assignments and solution conformation of the DNA.RNA hybrid duplex d(GTGAACTT).r(AAGUUCAC) Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;215:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheatham T.E., Kollman P.A. Molecular dynamics simulations highlight the structural differences among DNA:DNA, RNA:RNA, and DNA:RNA hybrid duplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:4805–4825. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong Y., Sundaralingam M. Crystal structure of a DNA.RNA hybrid duplex with a polypurine RNA r(gaagaagag) and a complementary polypyrimidine DNA d(CTCTTCTTC) Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2171–2176. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubins D.N., Lee A., Chalikian T.V. On the stability of double stranded nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:9254–9259. doi: 10.1021/ja004309u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall K.B., McLaughlin L.W. Thermodynamic and structural properties of pentamer DNA.DNA, RNA.RNA, and DNA.RNA duplexes of identical sequence. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10606–10613. doi: 10.1021/bi00108a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesnik E.A., Freier S.M. Relative thermodynamic stability of DNA, RNA, and DNA:RNA hybrid duplexes: relationship with base composition and structure. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10807–10815. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts R.W., Crothers D.M. Stability and properties of double and triple helices: dramatic effects of RNA or DNA backbone composition. Science. 1992;258:1463–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.1279808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cluzel P., Lebrun A., Caron F. DNA: an extensible molecule. Science. 1996;271:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith S.B., Cui Y., Bustamante C. Overstretching B-DNA: the elastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 1996;271:795–799. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipfert J., Skinner G.M., Dekker N.H. Double-stranded RNA under force and torque: similarities to and striking differences from double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15408–15413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407197111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abels J.A., Moreno-Herrero F., Dekker N.H. Single-molecule measurements of the persistence length of double-stranded RNA. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2737–2744. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrero-Galán E., Fuentes-Perez M.E., Arias-Gonzalez J.R. Mechanical identities of RNA and DNA double helices unveiled at the single-molecule level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:122–131. doi: 10.1021/ja3054755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arias-Gonzalez J.R. Single-molecule portrait of DNA and RNA double helices. Integr. Biol. 2014;6:904–925. doi: 10.1039/c4ib00163j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camunas-Soler J., Ribezzi-Crivellari M., Ritort F. Elastic properties of nucleic acids by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2016;45:65–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-011158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bustamante C., Bryant Z., Smith S.B. Ten years of tension: single-molecule DNA mechanics. Nature. 2003;421:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature01405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bustamante C., Smith S.B., Smith D. Single-molecule studies of DNA mechanics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang M.D., Yin H., Block S.M. Stretching DNA with optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouchiat C., Wang M.D., Croquette V. Estimating the persistence length of a worm-like chain molecule from force-extension measurements. Biophys. J. 1999;76:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumann C.G., Smith S.B., Bustamante C. Ionic effects on the elasticity of single DNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6185–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wenner J.R., Williams M.C., Bloomfield V.A. Salt dependence of the elasticity and overstretching transition of single DNA molecules. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3160–3169. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75658-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odijk T. Stiff chains and filaments under tension. Macromolecules. 1995;28:7016–7018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bercy M., Bockelmann U. Hairpins under tension: RNA versus DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:9928–9936. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collin D., Ritort F., Bustamante C. Verification of the Crooks fluctuation theorem and recovery of RNA folding free energies. Nature. 2005;437:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen J.D., Lancaster L., Tinoco I. Following translation by single ribosomes one codon at a time. Nature. 2008;452:598–603. doi: 10.1038/nature06716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu X., Wen J.D., Tinoco I., Jr. The ribosome uses two active mechanisms to unwind messenger RNA during translation. Nature. 2011;475:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hansen T.M., Reihani S.N., Sørensen M.A. Correlation between mechanical strength of messenger RNA pseudoknots and ribosomal frameshifting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5830–5835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608668104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strick T., Allemand J., Bensimon D. Twisting and stretching single DNA molecules. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2000;74:115–140. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X., Chen H., Yan J. Two distinct overstretched DNA structures revealed by single-molecule thermodynamics measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8103–8108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109824109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Vlaminck I., Henighan T., Dekker C. Magnetic forces and DNA mechanics in multiplexed magnetic tweezers. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klaue D., Seidel R. Torsional stiffness of single superparamagnetic microspheres in an external magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:028302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.028302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson J.P., Angerer B., Loeb L.A. Incorporation of reporter-labeled nucleotides by DNA polymerases. Biotechniques. 2005;38:257–264. doi: 10.2144/05382RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paik D.H., Roskens V.A., Perkins T.T. Torsionally constrained DNA for single-molecule assays: an efficient, ligation-free method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.King G.A., Gross P., Peterman E.J. Revealing the competition between peeled ssDNA, melting bubbles, and S-DNA during DNA overstretching using fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3859–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213676110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X., Chen H., Yan J. Revealing the competition between peeled ssDNA, melting bubbles, and S-DNA during DNA overstretching by single-molecule calorimetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3865–3870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213740110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X., Qu Y., Yan J. Interconversion between three overstretched DNA structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16073–16080. doi: 10.1021/ja5090805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bosaeus N., El-Sagheer A.H., Norden B. Tension induces a base-paired overstretched DNA conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:15179–15184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213172109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fu H., Chen H., Yan J. Two distinct overstretched DNA states. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5594–5600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fu H., Chen H., Yan J. Transition dynamics and selection of the distinct S-DNA and strand unpeeling modes of double helix overstretching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3473–3481. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paik D.H., Perkins T.T. Overstretching DNA at 65 pN does not require peeling from free ends or nicks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3219–3221. doi: 10.1021/ja108952v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cocco S., Yan J., Marko J.F. Overstretching and force-driven strand separation of double-helix DNA. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2004;70:011910. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.011910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rouzina I., Bloomfield V.A. Force-induced melting of the DNA double helix 1. Thermodynamic analysis. Biophys. J. 2001;80:882–893. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams M.C., Wenner J.R., Bloomfield V.A. Entropy and heat capacity of DNA melting from temperature dependence of single molecule stretching. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1932–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76163-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.SantaLucia J., Jr. A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1460–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bosaeus N., El-Sagheer A.H., Nordén B. Force-induced melting of DNA--evidence for peeling and internal melting from force spectra on short synthetic duplex sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8083–8091. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ngo T.T., Zhang Q., Ha T. Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomes under tension directed by DNA local flexibility. Cell. 2015;160:1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ngo T.T., Yoo J., Ha T. Effects of cytosine modifications on DNA flexibility and nucleosome mechanical stability. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10813. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.