Abstract

Most neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the accumulation of protein aggregates, some of which are toxic to cells. Mounting evidence demonstrates that in several diseases, protein aggregates can pass from neuron to neuron along connected networks, although the role of this spreading phenomenon in disease pathogenesis is not completely understood. Here we briefly review the molecular and histopathological features of protein aggregation in neurodegenerative disease, we summarize the evidence for release of proteins from donor cells into the extracellular space, and we highlight some other mechanisms by which protein aggregates might be transmitted to recipient cells. We also discuss the evidence that supports a role for spreading of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis and some limitations of this model. Finally, we consider potential therapeutic strategies to target spreading of protein aggregates in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: neurodegenerative disease, protein aggregate, seeding, spreading

1. INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative diseases are a clinically heterogeneous group of illnesses, including Alzheimer disease (AD), primary tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Parkinson disease (PD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington disease (HD), and prion diseases [e.g., Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)]. These disorders encompass a range of symptoms and signs, including cognitive impairment, weakness, gait instability, mood imbalance, and psychosis. Although all these diseases are progressive and lead to death either by primary dysfunction of the central nervous system (CNS) or as a consequence of related medical complications, the latency from onset of symptoms to end-stage illness can range from several months to multiple decades. Despite multiple differences in these diseases’ clinical components and epidemiology, in the anatomical regions affected (e.g., brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, muscle), and in the cell types involved (e.g., neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes), there are several commonalities that may help in understanding the pathophysiology of these diseases. One of the most conspicuous of these shared features is the phenomenon of aggregation of endogenous proteins into misfolded, insoluble inclusions. For several neurodegenerative diseases, specific proteins begin to aggregate in characteristic regions early in the disease course, but in later stages additional regions become involved, often in a predictable pattern within anatomic regions that are transsynaptically connected. This observation has led to the hypothesis that protein aggregates can spread from one cell to another and from one brain region to another. While numerous questions remain unanswered regarding the mechanisms of this phenomenon and how alternative or complementary processes factor in, tremendous progress has been made over the last 40 years to increase our understanding of these proteinopathies. Here we review what is currently known about the cell biology of spreading of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases, outline some of the gaps in our understanding of this phenomenon, and highlight opportunities to translate this knowledge into rational, disease-modifying treatments.

2. HISTOPATHOLOGY OF DISEASES CHARACTERIZED BY SPREADING OF PROTEIN AGGREGATES

A comprehensive review of the molecular features and histopathology of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disease is beyond the scope of this review, but it is worth highlighting several findings and themes here. For detailed reviews of the molecular basis of neurodegenerative diseases and disease-specific protein aggregates, the reader is referred to the following: AD and tauopathies (Holtzman et al. 2011, McKee et al. 2016, Spillantini & Goedert 2013, Walker et al. 2016), PD and α-synucleinopathies (Kalia & Lang 2016, Peng et al. 2018, Wong & Krainc 2017), ALS and FTD (Brettschneider et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2011, Taylor et al. 2016), HD (Ross et al. 2014), and prion disease (Colby & Prusiner 2011).

2.1. Prion Disease

Accumulation of aggregated material in the brains of patients with neurodegenerative disease has been recognized for more than 100 years, with initial studies utilizing basic histological techniques such as silver staining (Alzheimer 1907, Lewy 1912). Yet it took nearly eight decades until the description of a proteinaceous infectious particle as the causative agent of scrapie, a degenerative CNS disease in sheep and goats, first raised the possibility that proteins themselves could independently drive the propagation of additional misfolded proteins (Prusiner 1982). Several human neurodegenerative diseases, including CJD, are now known to result from the pathological conversion of the normal conformation of the prion protein (termed PrPC) into a misfolded conformation (PrPSc) that is capable of recruiting and converting additional molecules of PrPC into misfolded PrPSc, which is characterized by filamentous Congo red–positive amyloid structures that exhibit resistance to protease degradation (Colby & Prusiner 2011). Although widespread in the brains of affected patients, PrPSc does appear to spread along neuroanatomical pathways in certain contexts, and this process may be regulated by specific cell biological properties of specific forms of PrP, including membrane anchoring (Fraser 1982, Rangel et al. 2014).

2.2. Alzheimer Disease

Extracellular amyloid plaques composed of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated, aggregated forms of the microtubule-associated protein tau are the two hallmark pathological features of AD (Glenner & Wong 1984, Grundke-Iqbal et al. 1986). Careful observations of human autopsy series and functional imaging have demonstrated that Aβ tends to aggregate within anatomically and functionally connected brain regions, including the default mode network (Braak & Braak 1997, Buckner et al. 2005, Sperling et al. 2009). Similarly, in AD, tau aggregation initially occurs in the locus coeruleus and transentorhinal region during normal aging and later spreads to connected regions, including the hippocampus and specific regions of the neocortex (Braak & Braak 1997, Braak & Del Tredici 2011). Results from experimental model systems, including stereotaxic injection of enriched Aβ or tau seeds, have corroborated that seeding of protein aggregates followed by intercellular spreading of these aggregates can be induced in vivo (Clavaguera et al. 2009, Meyer-Luehmann et al. 2006). Tau also accumulates in a spectrum of neurodegenerative illnesses in addition to AD (classified as tauopathies) with characteristic predisposition for specific cell types and brain regions. In some experimental models, specific conformations, or strains, of tau aggregates (e.g., derived from AD, in which tau localizes to intraneuronal inclusions, versus CBD, in which tau aggregates prominently in both neurons and astrocytic plaques) are maintained during transmission in vivo and influence the regional spread of tau pathology, lending support to the hypothesis that tau behaves similarly to the prion protein by directing its own templated aggregation (Boluda et al. 2015, Kaufman et al. 2016, Sanders et al. 2014).

2.3. Parkinson Disease

Alpha synuclein (αSyn) is an abundant neuronal protein that is normally expressed in the cytosol or is associated with presynaptic membranes. αSyn aggregates as the principal component of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in PD and the related illness dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (Braak et al. 2003, Del Tredici et al. 2002, Kraybill et al. 2005, Polymeropoulos et al. 1997, Spillantini et al. 1997), as well as in the distinct synucleinopathy termed MSA (Tu et al. 1998). As with tauopathies, cell type and regional differences in the pattern of αSyn accumulation correspond to distinct clinical syndromes (Peng et al. 2018). In addition, experiments in animal model systems have shown that injection of aggregated αSyn, either from recombinant protein or purified from brains of patients with distinct synucleinopathies, induces templated propagation of αSyn pathology that can retain structural features of the original inoculum (Desplats et al. 2009; Luk et al. 2012a,b; Masuda-Suzukake et al. 2013; Peelaerts et al. 2015; Prusiner et al. 2015; Recasens et al. 2014; Watts et al. 2013). These findings argue that distinct aggregated αSyn conformations behave in a prion-like manner and can transmit their properties from cell to cell. Furthermore, autopsy studies of a small number of PD patients who received grafts of fetal mesencephalic transplants demonstrated Lewy pathology in the grafted neurons, providing additional evidence that aggregated αSyn can propagate from diseased to healthy neurons (Kordower et al. 2008, Li et al. 2008).

2.4. Frontotemporal Lobar Dementia and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Although clinically very distinct, FTD [pathologically defined as frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)] and ALS share the pathological hallmark of aggregates containing a 43-kDa TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) (Neumann et al. 2006). Phosphorylated and ubiquitinated inclusions of TDP-43 deposit in neurons and glia in multiple regions of the brain and spinal cord, and TDP-43 is now recognized as the defining molecular feature of a class of proteinopathies that result in multiple neurological symptoms ranging from motor neuron disease to dementia (Geser et al. 2010). While there is not as much direct evidence of TDP-43 spreading in vivo compared to other proteinopathies, human studies reveal an asymmetry in TDP-43 pathology across brain regions, suggesting differential aggregation that may depend on spreading rates or efficiency, and experiments in cultured cells support the possibility of transfer of aggregated TDP-43 from cell to cell (Feiler et al. 2015, Irwin et al. 2018, Nonaka et al. 2013).

For another disease-associated protein in ALS, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), the relationship between SOD1 aggregation and disease pathophysiology is less clear. Mutations in SOD1 were originally linked to dominantly inherited forms of familial ALS, which account for approximately 10% or fewer of total disease cases (Rosen et al. 1993). Subsequent work identified misfolded SOD1 protein in the motor neurons and glia in the spinal cord and other tissues from sporadic ALS (sALS) patients, suggesting that SOD1 protein aggregation was independent of disease-causing mutations in the gene (Bosco et al. 2010, Grad et al. 2014). However, other studies have not detected SOD1 aggregation in sALS, raising the possibility that the appearance of aggregated SOD1 staining in sALS is due to artifact (Brotherton et al. 2012, Da Cruz et al. 2017, Liu et al. 2009). Regardless of the presence or degree of an insoluble fibrillar form in vulnerable regions in sALS, SOD1 could still exert a deleterious effect on motor neurons through a relatively soluble intermediate oligomer structure (Sangwan et al. 2017), as is posited for several other neurodegenerative disease–related proteins. While there is some evidence in cell culture and in vivo for transmissibility of aggregates of mutant SOD1 (Ayers et al. 2014, 2016; Pokrishevsky et al. 2016, 2017), this phenomenon has only begun to be tested for wild-type SOD1 (Pokrishevsky et al. 2016), and more studies are needed to better understand the role of SOD1 aggregation and toxicity in sALS.

More recently, genetic linkage studies identified hexanucleotide repeat expansions in a noncoding region of C9ORF72 on chromosome 9p21 as the most common genetic cause of ALS and FTD (DeJesus-Hernandez et al. 2011, Renton et al. 2011). Insoluble inclusions containing the dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs) produced by noncanonical translation of this hexanucleotide repeat are found in multiple CNS regions of C9orf72-linked ALS/FTD patients (Ash et al. 2013), and there is emerging evidence that these DPRs may spread from cell to cell (Westergard et al. 2016).

2.5. Huntington Disease

HD is caused by a trinucleotide CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene, which codes for the protein huntingtin (Htt). Nonaffected individuals typically have fewer than 26 repeats, while in individuals with more than 40 repeats, the resulting mutant Htt protein (mHtt) is prone to cleavage, generating fragments that aggregate and become deposited in neuronal inclusions, thus leading to cell toxicity. While direct evidence for spreading of aggregated mHtt protein in vivo is lacking, there are several clues that mHtt aggregation may follow a templated aggregation process similar to that of other neurodegenerative disease proteins. Polyglutamine peptide aggregates can enter the cytoplasmic space of cultured cells, where they can drive aggregation of homologous proteins (Ren et al. 2009). Examination of early neonatal HD mouse models revealed an apparent progression of aggregates along axon tracts during development (Osmand et al. 2016), and autopsy studies of HD patients who received grafts of striatal tissue demonstrated the presence of mHtt protein within the grafted tissue (Cicchetti et al. 2014).

2.6. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

CTE is a distinct neurodegenerative disease characterized by irritability; impulsivity; depression; memory loss; executive dysfunction; increased risk of suicide; and occasionally motor symptoms such as parkinsonism, that occurs as a consequence of repetitive head trauma, often with a latency period of years or even decades (Stern et al. 2013). Pathologically, CTE is characterized by the accumulation of insoluble, hyperphosphorylated tau (and TDP-43) with a distinct distribution around small blood vessels at the depths of cortical sulci. Notably, certain tau epitopes commonly seen in AD pathology, as well as amyloid plaques, are not uniformly observed, indicating that CTE is a separate neuropathological disease (Kanaan et al. 2016, McKee et al. 2016). The exact mechanism of development of pathology in CTE is not completely understood, but CTE is thought to result from linear and rotational acceleration-deceleration forces that damage axons and blood vessels through a combination of enzyme activation, membrane permeabilization, calcium influx, compromise of blood-brain-barrier integrity, and phosphorylation and mislocation of tau (Kriegel et al. 2018). Postmortem examination of individuals with a history of repetitive head trauma demonstrated a range of distribution of pathology that appears to begin in deep cortical sulci near blood vessels and that is ultimately widespread in the neocortex, medial temporal lobe, cerebellum, brainstem, and even spinal cord (McKee et al. 2013). There is no direct evidence yet for tau spreading in human cases of CTE. However, the observation of early pathological tau aggregates near blood vessels localized in cortical sulci of individuals who died only a few years after injury contrasts with the widespread areas of neocortical tau pathology in individuals who died many years after brain injury, suggesting that spreading occurs. This finding, combined with reports of axonal injury and blood-brain-barrier disruption in contact sport players and following blast injury, provides a compelling mechanism by which pathological tau could spread from an initial site of injury and accumulate (Huber et al. 2016, Mac Donald et al. 2011).

3. MECHANISMS AND REGULATORY FACTORS AFFECTING SPREAD OF PROTEIN AGGREGATES

Following the observations that proteins aggregate in anatomically connected brain regions in multiple neurodegenerative diseases, significant progress has been made in understanding how this deposition occurs and specifically how the assembly of protein aggregates, many of which are primarily intracellular, may propagate from one cell to another.

3.1. Spontaneous Aggregation and Templated Propagation

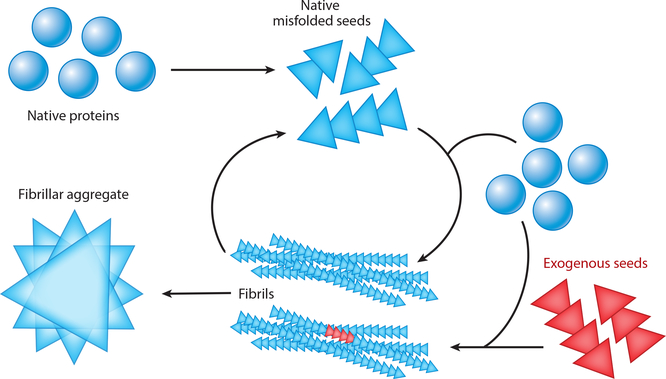

One important property of neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins is their ability to assemble in a templated fashion, either spontaneously or following inoculation with a seed of aggregated protein (Figure 1). Numerous disease-associated proteins have been shown to spontaneously assemble under specific conditions and to form amyloid structures with a fibrillar β-sheet structure. The biochemical and biophysical characteristics of protein self-assembly have been recently reviewed (Chiti & Dobson 2017), but several examples warrant highlighting here. Perhaps the most relevant to the pathological process of spreading is the ability of multiple disease-associated proteins to induce the templated aggregation of additional normal molecules of the same protein. The strongest evidence for this phenomenon comes from the prion protein literature, with multiple in vivo examples of templated assembly of normal prion protein induced by brain-derived or synthetic prions (Prusiner 2013).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of templated assembly of protein aggregates from spontaneous assembly of misfolded native protein or introduction of exogenous seeds. Briefly, native proteins (blue circles) may spontaneously misfold and subsequently propagate their misfolded conformation by templated recruitment of additional native proteins. These misfolded proteins can form oligomeric seeds (blue triangles). Misfolded seeds can continue to recruit native protein and self-assemble to form long, β-sheet-rich fibrils that ultimately form fibrillar aggregates. Alternatively, exogenous seeds (red triangles), either generated by another cell in a disease state or artificially introduced in experiments, may enter a cell and similarly recruit native proteins to form aggregates. Fibrils may also fragment into oligomers that may spur additional fibril formation within the same cell or that may spread to other cells to propagate protein misfolding and aggregation.

Experiments in transgenic mice harboring mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene APP demonstrated that inoculation of aggregated Aβ can induce seeding and spreading of β-amyloidosis (Meyer-Luehmann et al. 2006, Stöhr et al. 2012). More recent work further demonstrates this phenomenon in models that do not spontaneously develop pathology (Morales et al. 2012, Rosen et al. 2012), arguing that protein aggregation in this model represents a prion-like conversion, and not simply acceleration of inevitable disease. Similar work in transgenic mice expressing either mutant or wild-type human tau protein found that injection of either synthetic or brain-derived tau fibrils revealed a pattern of seeding and spreading of tau aggregates along neuroanatomical pathways that are known to be affected in spontaneous cases of AD in humans (Clavaguera et al. 2009, Iba et al. 2013). More recently, inoculation of human tau transgenic or wild-type mice with distinct strains of tau inclusions derived from cultured cells or brain extracts from patients with distinct tauopathies (AD, PSP, CBD) demonstrated that strain-specific tau pathology can be seeded and then propagated from cells to mice (Kaufman et al. 2016) and that tau strains from different human tauopathies induce spreading of tau pathology based primarily on the connections of the injection site (Boluda et al. 2015, Narasimhan et al. 2017). Interestingly, in the latter studies, brain extracts from PSP and CBD, in which there is significant glial tau pathology, recapitulated glial tau pathology, while AD extracts resulted in primarily neuronal pathology. Together, these results underscore the importance of the neuroanatomical connectome as well as the ability of intrinsic properties of misfolded tau to direct seeding followed by propagation in neurons and glia.

Stereotaxic injection of αSyn seeds, both from brain extract and as synthetic fibrils, triggers aggregation of both transgenic mutant and endogenous wild-type αSyn that then propagates along anatomic networks from multiple injection targets (Luk et al. 2012a,b; Paumier et al. 2015; Prusiner et al. 2015; Recasens et al. 2014; Rey et al. 2016). A smaller number of studies have reported direct transfer of αSyn to astrocytes and oligodendrocytes; this finding is of particular interest given that αSyn accumulates in oligodendrocytes in MSA (Lee et al. 2010, Reyes et al. 2014). Additional studies are needed to determine whether αSyn transferred from neurons can propagate in glia.

Huntingtin protein is known to self-assemble (Scherzinger et al. 1999), and fibroblasts and induced pluripotent stem cells from HD patients with expanded CAG repeats transmitted protein aggregates to normal mice (Jeon et al. 2016). Extracts from ALS and FTD brains have also been reported to induce templated aggregation of TDP-43 in neuronal cells (Nonaka et al. 2013). Taken together, these data indicate that multiple neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins are capable of aggregating in a templated manner and that such aggregation is directed in part by the properties of a seed that induces aggregation by a host of factors such as protein sequence, cell type, and neuronal network connectivity.

3.2. Cellular Exit of Aggregates

As many of the proteins noted to aggregate and spread in neurodegenerative diseases are natively intracellular, they likely require a mechanism to exit one cell before entering another (Figure 2). Given the cellular toxicity and neuron loss that are observed in many neurodegenerative diseases, one potential mechanism for release of intracellular proteins is leakage from damaged or dying neurons. For example, highly elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of tau protein are found in patients with CJD (Sanchez-Juan et al. 2006); such elevated levels are thought to be a consequence of acute and rapid neuron degeneration but are also found in other brain injury states, including ischemic stroke, infection, and metabolic derangement (Schraen-Maschke et al. 2008). Tau, Aβ, and αSyn are also present in CSF in healthy individuals, and while levels of total and phosphorylated tau are elevated in AD patients relative to controls, levels of Aβ and αSyn are lower in CSF from patients with AD and patients with PD, respectively, relative to controls, suggesting that extracellular release of these proteins is not simply a consequence of disease (Craig-Schapiro et al. 2009, Gao et al. 2015). Whether these and other proteins serve specific physiological roles in the extracellular space is still under investigation, but multiple studies in cultured neuronal cells and in vivo provide evidence for active, regulated release of several neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins into the extracellular space.

Figure 2.

Potential mechanisms for exit of native and misfolded proteins from a donor cell and entry of exogenous seeds into a recipient cell. Proteins from a donor cell (blue) can exit by one of at least three pathways: (a) direct secretion of the free protein into the extracellular space by a currently unknown mechanism, (b) secretion in exosomes, or (c) direct transfer through tunneling nanotubes (TNTs). While these mechanisms have been reported to occur under physiological conditions, the role of secretion/release of normally intracellular proteins in brain function is unclear. Once in the extracellular space, free exogenous seeds (red) may then be taken up by a recipient cell by (d) direct insertion through the plasma membrane, (e) fluid-phase endocytosis or macropinocytosis, or (f) receptor-mediated endocytosis. If taken up through an endosome (g), exogenous seeds can escape the vesicle into the cytosol through a mechanism that is unclear. Seeds delivered to a recipient cell by exosomes or TNTs are directly released into the intracellular space. Once exogenous seeds are in the cytosol of the recipient cell (h), they may begin recruiting native monomer (green) and initiate templated misfolding, leading to the formation of oligomers/fibrils and eventually aggregates in the recipient cell.

Aβ is generated by sequential cleavage of APP by the β-secretase and γ-secretase complex in endosomal compartments. Aβ is secreted predominantly into brain interstitial fluid in a free form (i.e., not inside vesicles) in a manner that is regulated by synaptic activity (Cirrito et al. 2005). Tau is also released into brain interstitial fluid in an activity-dependent manner, likely via an unconventional secretory pathway (Karch et al. 2012, Yamada et al. 2011). Studies in cultured cells indicate that αSyn, tau, and TDP-43 are secreted via an unconventional mechanism possibly involving chaperone proteins (Fontaine et al. 2016, Lee et al. 2005). αSyn is released into the brain interstitial fluid in both humans and mice; such release is potentially regulated by GABA receptors in conjunction with ATP-dependent K+ channels (Emmanouilidou et al. 2011, 2016). Notably, both tau and αSyn lack a canonical signal peptide, so their secretion would be presumed to follow an unconventional mechanism. In addition to the release of monomeric αSyn, there is evidence that αSyn oligomers are released from cultured neurons and can be taken up by adjacent neurons, also in a manner regulated by a chaperone protein (Danzer et al. 2011). The release of free forms of disease-associated proteins into the interstitial space may have important implications for some therapeutic interventions, as CNS delivery of antibodies targeting these proteins for degradation would likely encounter these proteins primarily in a free form.

Additional physiological mechanisms for release of intracellular proteins have been implicated in the transmission of neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins. Exosomes are ~50–150-nm vesicular structures that contain a variety of cellular material, including protein, and are released by numerous cell types, presumably as a means of intercellular transport of cargo (Raposo & Stoorvogel 2013). A well-established and growing literature implicates exosomes in the release of PrPSc, Aβ, tau, αSyn, SOD1, TDP-43, C9orf72 DPRs, and Htt. Although Aβ is largely released into the extracellular space as a free peptide, this process also occurs through exosomes following the fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane (Rajendran et al. 2006, Sharples et al. 2008). Tau is also released from neurons via exosomes in an activity-dependent manner and is detectable in CSF from AD patients in exosome-associated forms that promote tau aggregation (Saman et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2017). Hippocampal slice culture experiments show that exosome-associated tau can also be taken up by both neurons and microglia (Wang et al. 2017). Microglia also appear to release tau in exosomes, and inhibition of exosome synthesis and depletion of microglia reduced spreading of tau pathology in vivo (Asai et al. 2015).

Multiple laboratories have detected the secretion of αSyn by exosomes in cell-based assays, in which it is readily taken up by recipient cells and causes toxicity (Danzer et al. 2012, Emmanouilidou et al. 2010). More recently, it was shown that exosome-associated αSyn purified from CSF from patients with AD and DLB can be taken up by endocytosis and induces αSyn aggregation when injected into wild-type mouse brain (Ngolab et al. 2017). Consistent with this finding, another recent study reported an increase in extracellular exosome-associated αSyn following inhibition of the autophagy/lysosome pathway in cells and an increase in αSyn intraneuronal inclusions following injection of CSF exosomes from DLB patients as opposed to control CSF exosomes (Minakaki et al. 2018). Several proteins linked to FTD and ALS are released by exosomes. Both SOD1 and TDP-43 can be secreted from cultured cells in exosomes, and exosome-associated TDP-43 can be taken up by recipient cells, where it induces aggregation of TDP-43 and causes toxicity (Feiler et al. 2015, Iguchi et al. 2016). As with αSyn, blocking autophagy increased exosome secretion of TDP-43. Somewhat surprisingly, inhibition of exosome formation with a neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitor exacerbated TDP-43 aggregation in cells and worsened the phenotype of transgenic mutant TDP-43 mice (Iguchi et al. 2016). Together, these data argue for a complex role of exosomes in both physiological and pathological handling of TDP-43 by exosomes. C9orf72 DPRs have also been reported to be released in exosomes and can be transmitted to primary neurons in culture via conditioned medium (Westergard et al. 2016). These data strongly indicate that exosome secretion is an active, regulated mechanism by which many disease-associated proteins are released into the extracellular space and that exosome secretion may contribute to pathological spreading between cells.

3.3. Protein Uptake: Cell Surface Receptors, Endocytosis, and the Autophagy/Lysosome Pathway

Once monomeric or aggregated proteins exit one neuron, they can be taken up by neighboring cells, which may propagate the seeding and spreading process. Although much remains unclear about whether this uptake serves specific physiological purposes, significant progress has been made in recent years to characterize the cell biological mechanisms involved.

Aβ peptides are taken up by multiple cell types in the brain, including neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. This process is regulated by several molecules, including apolipoprotein E (apoE), which may serve as a chaperone protein for Aβ and in some instances facilitate uptake of Aβ but, in other circumstances, inhibit uptake (Verghese et al. 2013), in part through interaction with the apoE receptors LDLR and LRP1 (for a review, see Holtzman et al. 2012). There is also evidence that LRP1 participates in the clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier. While internalization of Aβ into astrocytes and microglia may represent a mechanism to clear and degrade Aβ or even to enhance seeding and spreading, uptake into neurons can result in accumulation of Aβ in multivesicular bodies and lysosomes and may ultimately be toxic to neurons.

Tau can also be taken up by endocytosis and subsequently transported along axons (Wu et al. 2013). Multiple forms of tau can be taken up by neurons, although the most pathologically relevant forms are still not clear. One recent study identified a soluble, phosphorylated high-molecular-weight species as being efficiently internalized and capable of propagating pathology in neurons (Takeda et al. 2015). The factors governing the uptake of specific forms of monomeric or aggregated tau in the brain are not completely understood, but experiments in cultured neurons and in vivo suggest a role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPs) in mediating internalization of aggregated forms of tau (Holmes et al. 2013). Sortilin, a lysosomal sorting receptor, was recently suggested to inhibit the propagation of tau pathology in vivo (Johnson et al. 2017). Recent studies have also implicated C9orf72 in endosomal trafficking through a mechanism involving Rab GTPases, with C9orf72 depletion leading to the accumulation of phosphorylated TDP-43 (Ciura et al. 2016, Farg et al. 2014).

Failure of lysosomal degradation and autophagy pathways has been implicated in the pathogenesis of synucleinopathies as well, although the precise mechanism of αSyn internalization in neurons also remains unclear (Cuervo et al. 2004). At least one study has suggested a role for HSPs in mediating αSyn uptake in a cell-based biosensor assay (Holmes et al. 2013), while another recent study did not find clear evidence for caveolin-dependent, clathrin-dependent, or macropinocytosis mechanisms in the uptake of αSyn (Delenclos et al. 2017). The latter finding is in contrast to work performed in a neuroblastoma cell line demonstrating a role for macropinocytosis induced by membrane ruffling in response to exposure to multiple protein aggregates, including SOD1, TDP-43, HTT, and αSyn (Zeineddine et al. 2015). Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), a transmembrane protein recently identified by a library screen for proteins that bind αSyn preformed fibrils (PFFs), was shown to be important for mediating αSyn PFF–induced αSyn pathology both in cultured neurons and in mice (Mao et al. 2016). In this study, LAG3-deficient mice were protected from αSyn PFF–induced neurodegeneration and motor impairment, and treatment with anti-LAG3 antibodies blocked the transmission of αSyn PFF–induced αSyn pathology in cultured neurons, suggesting that interventions targeted at cellular mechanisms of protein aggregate uptake may reduce neurodegeneration. Further work, including additional in vivo studies, is clearly needed to further define the cell biological mechanisms that regulate internalization, degradation, and propagation of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases.

3.4. Tunneling Nanotubes

Although contact-independent transfer between cells in the brain likely accounts for much of the transmission of protein aggregates, there is emerging evidence that mechanisms involving direct contact between cells may play a role as well. Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are thin (~50–200-nm), transiently lived membranous connections between cells that can span distances up to ~100 μm and facilitate the transfer of a variety of macromolecules and cellular structures, including nucleic acids, proteins, mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, and endosomes. Originally described in PC-12 neuroendocrine cells, TNTs have also been described in multiple mammalian cell types, including neurons (Gerdes et al. 2013, Onfelt et al. 2005, Rustom et al. 2004). In addition to having a putative role in normal cellular physiology, TNTs have also been shown to facilitate the transfer of viruses such as HIV and, more recently, a growing number of proteins involved in neurodegenerative disease. PrPSc was shown to transfer between cultured neuronal cells via TNTs, at least in part contained within endosomal/lysosomal vesicles (Gousset et al. 2009, Zhu et al. 2015). Importantly, PrPSc infection was shown to increase the number of TNT connections with neighboring cells, consistent with the observation in other cell types that TNT formation may be a stress response. TNTs have since been shown to participate in the intercellular transfer of PrPSc from astrocytes to neurons in culture, an interesting finding given the role of astrocytes in clearance of multiple proteins and the relationship between cellular stress and TNT formation (Victoria et al. 2016). TNTs have also been reported to mediate various processes, including the intercellular transfer of Aβ in astrocytes and possibly to neurons (Wang et al. 2011); interneuronal transfer of tau aggregates (Abounit et al. 2016b, Tardivel et al. 2016); neuron-to-neuron and astrocyte-to-astrocyte transmission of αSyn fibrils, including within lysosomal vesicles (Abounit et al. 2016a, Rostami et al. 2017); propagation of TDP-43 aggregates in cultured cells (Ding et al. 2015); and transfer of polyglutamine aggregates in cultured neurons (Costanzo et al. 2013). These data highlight TNTs as a highly relevant contact-dependent mode of protein aggregate transmission, especially in the context of cellular stress that is induced by the accumulation of insoluble protein aggregates within multiple cell types during the progression of neurodegenerative disease. Further work is needed to better characterize the cell types, organelle involvement, and the local environment triggers involved in TNT-mediated propagation of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disease and to clarify whether TNTs play a role in vivo. Whether this phenomenon will be a realistic therapeutic target in these illnesses remains to be determined.

3.5. Protein Aggregate Clearance Across the Blood-Brain Barrier and via the Glymphatic System

While some proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases are expressed in nonneuronal tissues, most are at least enriched in the nervous system. Detection of neuronal proteins—including Aβ, tau, αSyn and others—in the CSF, brain interstitial fluid, and plasma has prompted investigation into the mechanisms by which these proteins might be transported from the brain interstitial fluid into other compartments. By far the most detailed understanding of this process exists for Aβ, for which lipoprotein receptors, including LRP1 and LDLR, appear to participate in clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier, likely through multiple mechanisms, including some involving apoE (Holtzman et al. 2012). Less detail is known about active transport mechanisms for most other proteins, leading to speculation that active or tightly regulated transport mechanisms may not exist as they do for Aβ and that clearance of other proteins may rely more on bulk flow of interstitial fluid, CSF reabsorption, or other as-yet-undescribed mechanisms. One hypothesis that has attracted much attention recently is that of a glymphatic system in the brain; such a system is proposed to utilize convective solute transport driven by para-arterial pulsations that set up a hydrostatic pressure gradient tuned in part by aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels in astroglial end feet (Iliff et al. 2012). Mice deficient in Aqp4 exhibit impaired clearance of synthetic Aβ and accelerated tau pathology following experimental traumatic brain injury (Iliff et al. 2012, 2014), and sleep has been proposed to facilitate glymphatic system–mediated clearance of Aβ by increasing the brain interstitial volume (Xie et al. 2013). To date there is no direct evidence for clearance of other neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins via the glymphatic system, and although there are caveats to the interpretation of data from Aqp4-knockout experiments (Smith & Verkman 2018), the concept of the glymphatic system is intriguing and warrants further exploration, especially regarding ways in which it could be leveraged for potential therapies.

There has been tremendous progress over the last decade in the understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate protein aggregate release, uptake, and transmission in multiple brain cell types. With this expansion of knowledge, many new questions have arisen, including those driven by conflicting results. While reductionist experimental paradigms are valuable in the process of identifying and characterizing molecular mechanisms governing normal cell biology and disease states, one of the major challenges of the next phase of research in neurodegenerative disease will be to validate mechanistic findings by using longitudinal in vivo approaches. This strategy, although time consuming, likely offers the most promise for reconciling complex, and in some cases disparate, data into unifying models and identifying the most logical therapeutic targets for human trials.

4. CAVEATS TO USING PROTEIN AGGREGATION TO EXPLAIN NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

While protein aggregate spreading along transsynaptically connected networks is an attractive theory to explain the progressive accumulation of pathology in neurodegenerative disease, several important factors indicate that this phenomenon is not the exclusive pathophysiological mechanism underlying these illnesses.

First, the degree of protein aggregation in the hallmark pathological features does not always correlate well with the severity of clinical symptoms in several different diseases. This lack of robust association is true for Lewy bodies in PD and for certain forms of amyloid plaques in AD termed senile plaques, while other protein aggregates in AD, including neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, show a closer association with clinical symptoms (Arriagada et al. 1992, Parkkinen et al. 2005).

Second, protein aggregation does not always correlate with neurodegeneration in either the degree of severity or the neuroanatomic location. This is an important consideration due to the body of research linking aggregated forms of multiple proteins with cellular stress and neurotoxicity. In AD, neuron loss and synapse loss correlate with dementia severity, but not as closely with plaque and tangle burden (Andrade-Moraes et al. 2013, DeKosky & Scheff 1990). The initial location of amyloid plaque accumulation in AD does not overlap with the site of early neuron loss, although the pattern of accumulation of neurofibrillary tangle pathology does track more closely with neurodegeneration (Braak & Braak 1991). Similar phenomena are apparent in PD, including a recent stereological study that found no significant correlation between αSyn pathology and loss of substantia nigra neurons in both PD and incidental Lewy body disease (Iacono et al. 2015). In PD, there is a substantial discordance between the initial brain regions that accumulate Lewy pathology—the olfactory bulb and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve—and the most vulnerable site of neuron loss—the substantia nigra pars compacta (Jellinger 2009). Several factors may account for these discrepancies. For example, there is still much debate over the most toxic form of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disease, with accumulating evidence for oligomeric forms of Aβ, tau, and αSyn as the most cytotoxic species of each protein (Barrett & Greenamyre 2015, Brody et al. 2017, Shafiei et al. 2017). If this is true, mature, fibrillar forms of the aggregated protein may evolve as relics of a pathological cascade and may be relatively less harmful than more soluble oligomeric species. Detection and quantification of oligomeric species of proteins, especially in vivo, present technical challenges that are still being addressed, so further studies will be needed to better reconcile the relationship between specific aggregated forms of proteins and their role in neuronal injury and disease symptoms.

Third, cell- and region-autonomous factors likely contribute to the vulnerability of specific neurons to accumulate protein aggregates. For example, in AD, morphological features such as relatively thin myelination may underlie cellular vulnerability to tau pathology (Braak et al. 2000), region-specific neuronal activity chronically increases the formation of amyloid plaques in transgenic mice (Bero et al. 2011), and functionally connected neuronal networks appear to share regional vulnerability for tau pathology (Lewis & Dickson 2016). Similarly, in PD, vulnerable neurons tend to share common features, including rhythmic depolarization, fluctuations in calcium concentration, and a propensity for mitochondrial stress (Surmeier et al. 2017). Furthermore, despite the evidence for transsynaptic spread of αSyn in vitro and in vivo, Lewy pathology does not strictly follow a pattern of spreading along the connectome of vulnerable brain regions, as would be expected if aggregates were transmitted to adjacent neurons primarily on the basis of release and subsequent uptake by neighboring cells (Surmeier et al. 2017). Taken together, these data indicate that cell-to-cell propagation of aggregated proteins likely plays a role in the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disease but that this process occurs in the setting of a complex tissue architecture with multiple factors that regulate individual cell vulnerability and that this process may either facilitate or inhibit protein aggregate spreading (for a recent review, see Walsh & Selkoe 2016). Further work is needed to clarify these governing principles and determine whether they may be leveraged for therapeutic strategies.

Fourth, there is a remarkable diversity of clinical presentations across diseases that share common protein aggregates. For example, primary tauopathies typically display stereotypical patterns of cognitive and motor symptoms, with some but certainly not all of the diversity correlating with specific isoforms of tau that accumulate in a particular disease (Lewis & Dickson 2016, Spillantini & Goedert 2013). The synucleinopathies PD and DLB share enough molecular and pathological features that they may be viewed as points along a common spectrum, while MSA is clearly a distinct disease that happens to also share aggregated αSyn as its primary pathological hallmark (Peng et al. 2018, Wong & Krainc 2017). Multiple protein aggregates are found in several specific combinations of neurodegenerative diseases. For example, there is broad overlap of Aβ and αSyn (and, to a lesser extent, tau) pathology in AD and PD (Elahi & Miller 2017, Kalia & Lang 2016), and both tau and TDP-43 are present in pathological forms in FTLD and ALS (Brettschneider et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2011, Taylor et al. 2016). In addition to diversity in clinical phenotypes, there are distinct cellular patterns of accumulation of common protein aggregates. An excellent example of this phenomenon is in PSP and CBD; both PSP and CBD feature aggregates in neurons and astrocytes of an isoform of tau containing four repeats of the microtubule-binding domain, yet the characteristic aggregation patterns of tau in these two cell types is distinct (Yoshida 2014). Another example is the neuronal accumulation of αSyn in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in PD, in contrast to the aggregation of αSyn in glial cytoplasmic inclusions within oligodendrocytes in MSA (Peng et al. 2018). Even though there is some in vitro and animal model evidence for transmissibility of specific strains of misfolded proteins from distinct tauopathies and synucleinopathies, there are likely cell- and region-specific factors that predispose to certain aggregation patterns in humans, in whom many or even most cases are presumably not transmitted. Further work is needed to understand the genetic and cell biological contributors to the pathological diversity seen in neurodegenerative diseases.

5. TARGETING PROTEIN AGGREGATION SPREADING FOR DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPY

Multiple therapeutic approaches to neurodegenerative disease are centered on disrupting the spread of protein aggregation. Although no proven disease-modifying therapies have advanced to become the standard of care, multiple therapeutics are in human clinical trials, and basic research is ongoing.

Antibody therapeutics targeted against Aβ, αSyn, and tau are among the most extensively tested to date (Gallardo & Holtzman 2017, George & Brundin 2015, Tran et al. 2014). Human trials of active immunization against Aβ corroborated the finding in mice that this strategy reduced amyloid burden (Masliah et al. 2005a), but beneficial effects on cognitive status were generally lacking (Holmes et al. 2008), and an early trial, AN1792, was halted due to a serious adverse event of meningoencephalitis in multiple participants (Senior 2002). Additional active Aβ immunization trials are under way, with modifications to avoid the Th1 lymphocyte response that is believed to contribute to meningoencephalitis. At least two humanized anti-Aβ antibodies, bapineuzumab and solanezumab, have been used in phase III passive immunization trials, with some mixed results in terms of biomarker and clinical outcomes but complications related to Fcγ-related inflammation and development of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, including microhemorrhages with antibodies like bapinezumab that bind to aggregated forms of Aβ. Newer-generation antibodies such as aducanumab that bind to plaques and that are being used at higher doses have shown promise in removing plaques and in slowing cognitive decline in early studies (Sevigny et al. 2016). There are several potential explanations for this lack of robust effect of some of the previous trials, including (a) initiation of treatment at a point in disease progression at which Aβ is no longer the driver of disease progression and (b) the potential failure of several of these antibodies to engage and remove amyloid at the doses utilized. Additional studies are ongoing and will hopefully improve on the results to date. Both active and passive immunization strategies targeted toward αSyn reduce αSyn pathology and neurodegeneration and reduce motor impairment in transgenic and αSyn fibril–induced spreading rodent models (Mandler et al. 2014, Masliah et al. 2005b, Tran et al. 2014). Progress with vaccine trials for PD have lagged behind those for AD, although a small number of vaccine trials for αSyn in humans are currently in progress (Affiris AG 2014).

Immunization against tau has shown some promise in animal models, including effects on cognition and tau pathology (Bi et al. 2011, Boutajangout et al. 2010). A passive tau immunization study demonstrated that tau antibodies that blocked tau seeding activity in a biosensor cell line were the most efficacious at reducing tau pathology and improving cognition (Yanamandra et al. 2013), supporting the concept that targeting the spreading process of extracellular, nonvesicular tau is beneficial. Further supporting the concept of targeting pathological conformations of tau, another passive immunization study used an antitau antibody that specifically recognizes the cis conformation of phosphorylated tau found in the early stages of traumatic brain injury; this antibody blocked the spread of tau pathology and resulted in improved behavioral outcomes following traumatic brain injury in mice (Kondo et al. 2015). Human studies with both active and passive tau immunization are currently under way (West et al. 2017).

A recent study using a model of tau aggregation highlighted how a conserved cell biological mechanism thought to be part of the immune response to pathogens may be repurposed to clear protein aggregates at a posttranslational stage. Tripartite motif protein 21 (TRIM21) is a highly conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase with high affinity to the Fc domain of antibodies. During infection by some viruses, antibodies recognizing the virus are also translocated to the cytoplasm, where the pathogen-antibody complex is recognized by TRIM21 and is targeted for destruction by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. This observation led to the hypothesis that this system could be leveraged to target posttranslational degradation of specific proteins by taking advantage of antibody-antigen specificity (Clift et al. 2017). Disruption of TRIM21 by CRISPR/Cas9 led to significantly increased tau seeding when a tau biosensor cell line was challenged with tau seeds along with antitau antibodies (McEwan et al. 2017).

Several additional approaches to intervening in the process of protein aggregate spreading have shown promise in preclinical models. Several strategies to induce or enhance autophagy, including pharmacological activation and a viral vector approach using heat shock cognate protein 70, have demonstrated improvement in pathology in models of aggregation of TDP-43, αSyn, SOD1, and HTT (Bauer et al. 2010, Kim et al. 2013, Steele et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2012).

6. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

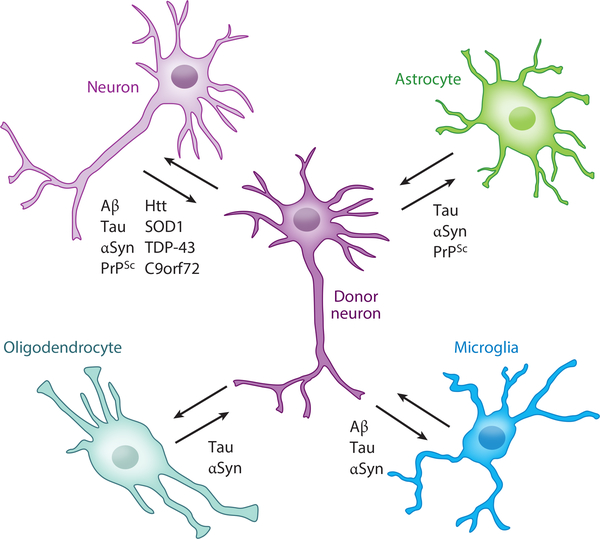

In the nearly 40 years since the PrPSc protein was first shown to transmit intercellular misfolding of native PrPC protein, tremendous progress has been made in understanding how protein spreading contributes to pathology in a range of neurodegenerative diseases. Detailed biochemical and biophysical studies point to a spontaneous but regulated aggregation process by which endogenous, usually soluble proteins with established or putative physiological roles assemble into insoluble, fibrillar species. Differences in the protein aggregates themselves, in the cell types involved, and in the anatomic regions affected by specific protein aggregates may help explain the incredible diversity in symptoms and progression rates across various diseases. Once thought to reside in the cells in which they are translated, neuronal proteins are now known to exit cells in an active manner and, once in the extracellular space, to interact with other macromolecules and enter neighboring neurons as well as glia (Figure 3). Distinct cell biological mechanisms, both contact dependent and contact independent, participate in the transfer of protein aggregates among brain cells. Developing theories are now beginning to elucidate the steps in this complex process that are reminiscent of normal physiology versus those that represent a breakdown in cell biological quality control.

Figure 3.

Transfer of neurodegenerative disease–associated proteins between central-nervous-system cell types. The majority of proteins that aggregate in neurodegenerative diseases originate in neurons, and aggregates can be transferred to multiple cell types, including other neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. Examples of transfer of specific proteins between particular cell types are indicated. Abbreviations: αSyn, alpha synuclein; Aβ, amyloid-β peptide; Htt, huntingtin; PrPSc, misfolded prion protein; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TDP-43, 43-kDa TAR DNA-binding protein.

Despite this progress, critical questions remain to be answered before new rationally designed therapies can be implemented to combat these disorders. What are the relative contributions of specific protein conformations or aggregation stages to the spreading process and cellular toxicity? Accumulating evidence suggests that soluble oligomeric species rather than mature fibrillar aggregates are the most deleterious, but further work is needed to understand how transient versus stable these oligomers are and how they are processed by neurons and glia. What are the normal physiological functions, if any, that could be served by the release of neurodegenerative disease–associated intracellular proteins? Related to this topic, if endosomal/lysosomal targeting of protein aggregates represents a quality control mechanism that fails in disease states, what are the contributors of this failure in the context of specific proteins and specific diseases? Finally, what are the mechanisms that dictate vulnerability of specific cell types and brain regions to accumulation of certain protein aggregates? Addressing these challenges will help pave the way to novel disease-modifying treatments for a class of devastating neurological diseases.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

D.M.H. is on the scientific advisory boards of C2N Diagnostics, Denali, Genentech, and Proclara Biosciences. D.M.H. and C.E.G.L. are listed as inventors on a patent licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics for the therapeutic use of antitau antibodies. This antitau antibody program was licensed by C2N Diagnostics to AbbVie. A.A.D. is the recipient of an NIH K08 award to study α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson disease dementia.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abounit S, Bousset L, Loria F, Zhu S, de Chaumont F, et al. 2016a. Tunneling nanotubes spread fibrillar α-synuclein by intercellular trafficking of lysosomes. EMBO J. 35:2120–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abounit S, Wu JW, Duff K, Victoria GS, Zurzolo C. 2016b. Tunneling nanotubes: a possible highway in the spreading of tau and other prion-like proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Prion 10:344–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affiris AG. 2014. Studies assessing tolerability and safety of AFFITOPE® PD03A in patients with early Parkinson’s disease (AFF011). Rep. NCT02267434, US Natl. Libr. Med., Natl. Inst. Health, Washington, DC: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02267434 [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer A 1907. Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg. Z. Psychiatr 64:146–48 [Google Scholar]

- Andrade-Moraes CH, Oliveira-Pinto AV, Castro-Fonseca E, da Silva CG, Guimaraes DM, et al. 2013. Cell number changes in Alzheimer’s disease relate to dementia, not to plaques and tangles. Brain 136:3738–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. 1992. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42:631–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai H, Ikezu S, Tsunoda S, Medalla M, Luebke J, et al. 2015. Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat. Neurosci 18:1584–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash PE, Bieniek KF, Gendron TF, Caulfield T, Lin WL, et al. 2013. Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 77:639–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JI, Fromholt S, Koch M, DeBosier A, McMahon B, et al. 2014. Experimental transmissibility of mutant SOD1 motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 128:791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JI, Fromholt SE, O’Neal VM, Diamond JH, Borchelt DR. 2016. Prion-like propagation of mutant SOD1 misfolding and motor neuron disease spread along neuroanatomical pathways. Acta Neuropathol. 131:103–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PJ, Greenamyre JT. 2015. Post-translational modification of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1628:247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PO, Goswami A, Wong HK, Okuno M, Kurosawa M, et al. 2010. Harnessing chaperone-mediated autophagy for the selective degradation of mutant huntingtin protein. Nat. Biotechnol 28:256–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero AW, Yan P, Roh JH, Cirrito JR, Stewart FR, et al. 2011. Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat. Neurosci 14:750–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi M, Ittner A, Ke YD, Gotz J, Ittner LM. 2011. Tau-targeted immunization impedes progression of neurofibrillary histopathology in aged P301L tau transgenic mice. PLOS ONE 6:e26860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boluda S, Iba M, Zhang B, Raible KM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. 2015. Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer’s disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol. 129:221–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco DA, Morfini G, Karabacak NM, Song Y, Gros-Louis F, et al. 2010. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat. Neurosci 13:1396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. 2010. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau prevents cognitive decline in a new tangle mouse model. J. Neurosci 30:16559–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82:239–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. 1997. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol. Aging 18:351–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K. 2011. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 121:171–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. 2003. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24:197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Del Tredici K, Schultz C, Braak E. 2000. Vulnerability of select neuronal types to Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 924:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Toledo JB, Robinson JL, Irwin DJ, et al. 2013. Stages of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol 74:20–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DL, Jiang H, Wildburger N, Esparza TJ. 2017. Non-canonical soluble amyloid-β aggregates and plaque buffering: controversies and future directions for target discovery in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther 9:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton TE, Li Y, Cooper D, Gearing M, Julien JP, et al. 2012. Localization of a toxic form of superoxide dismutase 1 protein to pathologically affected tissues in familial ALS. PNAS 109:5505–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, et al. 2005. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J. Neurosci 25:7709–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F, Dobson CM. 2017. Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem 86:27–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti F, Lacroix S, Cisbani G, Vallieres N, Saint-Pierre M, et al. 2014. Mutant huntingtin is present in neuronal grafts in Huntington disease patients. Ann. Neurol 76:31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Yamada KA, Finn MB, Sloviter RS, Bales KR, et al. 2005. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-β levels in vivo. Neuron 48:913–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciura S, Sellier C, Campanari ML, Charlet-Berguerand N, Kabashi E. 2016. The most prevalent genetic cause of ALS-FTD, C9orf72 synergizes the toxicity of ATXN2 intermediate polyglutamine repeats through the autophagy pathway. Autophagy 12:1406–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, et al. 2009. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:909–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clift D, McEwan WA, Labzin LI, Konieczny V, Mogessie B, et al. 2017. A method for the acute and rapid degradation of endogenous proteins. Cell 171:1692–706.e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby DW, Prusiner SB. 2011. Prions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3:a006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M, Abounit S, Marzo L, Danckaert A, Chamoun Z, et al. 2013. Transfer of polyglutamine aggregates in neuronal cells occurs in tunneling nanotubes. J. Cell Sci. 126:3678–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Schapiro R, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM. 2009. Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis 35:128–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. 2004. Impaired degradation of mutant α-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 305:1292–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz S, Bui A, Saberi S, Lee SK, Stauffer J, et al. 2017. Misfolded SOD1 is not a primary component of sporadic ALS. Acta Neuropathol. 134:97–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Kranich LR, Ruf WP, Cagsal-Getkin O, Winslow AR, et al. 2012. Exosomal cell-to-cell transmission of alpha synuclein oligomers. Mol. Neurodegener 7:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer KM, Ruf WP, Putcha P, Joyner D, Hashimoto T, et al. 2011. Heat-shock protein 70 modulates toxic extracellular α-synuclein oligomers and rescues trans-synaptic toxicity. FASEB J. 25:326–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, et al. 2011. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p–linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72:245–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. 1990. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann. Neurol 27:457–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Tredici K, Rub U, De Vos RA, Bohl JR, Braak H. 2002. Where does Parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 61:413–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delenclos M, Trendafilova T, Mahesh D, Baine AM, Moussaud S, et al. 2017. Investigation of endocytic pathways for the internalization of exosome-associated oligomeric α-synuclein. Front. Neurosci 11:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, et al. 2009. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. PNAS 106:13010–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Ma M, Teng J, Teng RK, Zhou S, et al. 2015. Exposure to ALS-FTD-CSF generates TDP-43 aggregates in glioblastoma cells through exosomes and TNTs-like structure. Oncotarget 6:24178–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elahi FM, Miller BL. 2017. A clinicopathological approach to the diagnosis of dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol 13:457–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Elenis D, Papasilekas T, Stranjalis G, Gerozissis K, et al. 2011. Assessment of α-synuclein secretion in mouse and human brain parenchyma. PLOS ONE 6:e22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Melachroinou K, Roumeliotis T, Garbis SD, Ntzouni M, et al. 2010. Cell-produced α-synuclein is secreted in a calcium-dependent manner by exosomes and impacts neuronal survival. J. Neurosci 30:6838–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E, Minakaki G, Keramioti MV, Xylaki M, Balafas E, et al. 2016. GABA transmission via ATP-dependent K+ channels regulates α-synuclein secretion in mouse striatum. Brain 139:871–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farg MA, Sundaramoorthy V, Sultana JM, Yang S, Atkinson RA, et al. 2014. C9ORF72, implicated in amytrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia, regulates endosomal trafficking. Hum. Mol. Genet 23:3579–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiler MS, Strobel B, Freischmidt A, Helferich AM, Kappel J, et al. 2015. TDP-43 is intercellularly transmitted across axon terminals. J. Cell Biol. 211:897–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine SN, Zheng D, Sabbagh JJ, Martin MD, Chaput D, et al. 2016. DnaJ/Hsc70 chaperone complexes control the extracellular release of neurodegenerative-associated proteins. EMBO J. 35:1537–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser H 1982. Neuronal spread of scrapie agent and targeting of lesions within the retino-tectal pathway. Nature 295:149–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo G, Holtzman DM. 2017. Antibody therapeutics targeting Aβ and tau. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 7:a024331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Tang H, Nie K, Wang L, Zhao J, et al. 2015. Cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Neurosci 125:645–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S, Brundin P. 2015. Immunotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: micromanaging α-synuclein aggregation. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 5:413–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes HH, Rustom A, Wang X. 2013. Tunneling nanotubes, an emerging intercellular communication route in development. Mech. Dev 130:381–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geser F, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. 2010. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Neuropathology 30:103–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. 1984. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 120:885–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousset K, Schiff E, Langevin C, Marijanovic Z, Caputo A, et al. 2009. Prions hijack tunnelling nanotubes for intercellular spread. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:328–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad LI, Pokrishevsky E, Silverman JM, Cashman NR. 2014. Exosome-dependent and independent mechanisms are involved in prion-like transmission of propagated Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase misfolding. Prion 8:331–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M, Tung YC, Zaidi MS, Wisniewski HM. 1986. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem 261:6084–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, et al. 2013. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. PNAS 110:E3138–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, et al. 2008. Long-term effects of Aβ42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet 372:216–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G. 2012. Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2:a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. 2011. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci. Trans. Med 3:77sr1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber BR, Meabon JS, Hoffer ZS, Zhang J, Hoekstra JG, et al. 2016. Blast exposure causes dynamic microglial/macrophage responses and microdomains of brain microvessel dysfunction. Neuroscience 319:206–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono D, Geraci-Erck M, Rabin ML, Adler CH, Serrano G, et al. 2015. Parkinson disease and incidental Lewy body disease: just a question of time? Neurology 85:1670–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba M, Guo JL, McBride JD, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2013. Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. J. Neurosci 33:1024–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi Y, Eid L, Parent M, Soucy G, Bareil C, et al. 2016. Exosome secretion is a key pathway for clearance of pathological TDP-43. Brain 139:3187–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Chen MJ, Plog BA, Zeppenfeld DM, Soltero M, et al. 2014. Impairment of glymphatic pathway function promotes tau pathology after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci 34:16180–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, et al. 2012. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci. Trans. Med 4:147ra11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Xie SX, Rascovsky K, Van Deerlin VM, et al. 2018. Asymmetry of post-mortem neuropathology in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 141:288–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA. 2009. A critical evaluation of current staging of α-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1792:730–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon I, Cicchetti F, Cisbani G, Lee S, Li E, et al. 2016. Human-to-mouse prion-like propagation of mutant huntingtin protein. Acta Neuropathol. 132:577–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NR, Condello C, Guan S, Oehler A, Becker J, et al. 2017. Evidence for sortilin modulating regional accumulation of human tau prions in transgenic mice. PNAS 114:E11029–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia LV, Lang AE. 2016. Parkinson disease in 2015: evolving basic, pathological and clinical concepts in PD. Nat. Rev. Neurol 12:65–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan NM, Cox K, Alvarez VE, Stein TD, Poncil S, McKee AC. 2016. Characterization of early pathological tau conformations and phosphorylation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 75:19–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM, Jeng AT, Goate AM. 2012. Extracellular tau levels are influenced by variability in tau that is associated with tauopathies. J. Biol. Chem 287:42751–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman SK, Sanders DW, Thomas TL, Ruchinskas AJ, Vaquer-Alicea J, et al. 2016. Tau prion strains dictate patterns of cell pathology, progression rate, and regional vulnerability in vivo. Neuron 92:796–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim TY, Cho KS, Kim HN, Koh JY. 2013. Autophagy activation and neuroprotection by progesterone in the G93A-SOD1 transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis 59:80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo A, Shahpasand K, Mannix R, Qiu J, Moncaster J, et al. 2015. Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis P-tau blocks brain injury and tauopathy. Nature 523:431–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. 2008. Lewy body–like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Med 14:504–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, et al. 2005. Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology 64:2069–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegel J, Papadopoulos Z, McKee AC. 2018. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Is latency in symptom onset explained by tau propagation? Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 8:a024059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EB, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. 2011. Gains or losses: molecular mechanisms of TDP43-mediated neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 13:38–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Patel S, Lee SJ. 2005. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of α-synuclein and its aggregates. J. Neurosci 25:6016–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Suk JE, Patrick C, Bae EJ, Cho JH, et al. 2010. Direct transfer of α-synuclein from neuron to astroglia causes inflammatory responses in synucleinopathies. J. Biol. Chem 285:9262–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Dickson DW. 2016. Propagation of tau pathology: hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies. Acta Neuropathol. 131:27–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewy FH. 1912. Paralysis agitans. I. Pathologische Anatomie In Handbuch der Neurologie, ed. Lewandowsky M, pp. 920–33. Berlin: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, et al. 2008. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat. Med 14:501–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HN, Sanelli T, Horne P, Pioro EP, Strong MJ, et al. 2009. Lack of evidence of monomer/misfolded superoxide dismutase-1 in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol 66:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Kehm V, Carroll J, Zhang B, O’Brien P, et al. 2012a. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338:949–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Kehm VM, Zhang B, O’Brien P, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. 2012b. Intracerebral inoculation of pathological α-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathy in mice. J. Exp. Med 209:975–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Donald CL, Johnson AM, Cooper D, Nelson EC, Werner NJ, et al. 2011. Detection of blast-related traumatic brain injury in U.S. military personnel. New Engl. J. Med 364:2091–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler M, Valera E, Rockenstein E, Weninger H, Patrick C, et al. 2014. Next-generation active immunization approach for synucleinopathies: implications for Parkinson’s disease clinical trials. Acta Neuropathol. 127:861–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Hansen L, Adame A, Crews L, Bard F, et al. 2005a. Aβ vaccination effects on plaque pathology in the absence of encephalitis in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 64:129–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, et al. 2005b. Effects of α-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 46:857–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda-Suzukake M, Nonaka T, Hosokawa M, Oikawa T, Arai T, et al. 2013. Prion-like spreading of pathological α-synuclein in brain. Brain 136:1128–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Ou MT, Karuppagounder SS, Kam TI, Yin X, et al. 2016. Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiated by binding lymphocyte-activation gene 3. Science 353:aah3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan WA, Falcon B, Vaysburd M, Clift D, Oblak AL, et al. 2017. Cytosolic Fc receptor TRIM21 inhibits seeded tau aggregation. PNAS 114:574–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, et al. 2016. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 131:75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, et al. 2013. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136:43–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, et al. 2006. Exogenous induction of cerebral β-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science 313:1781–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakaki G, Menges S, Kittel A, Emmanouilidou E, Schaeffner I, et al. 2018. Autophagy inhibition promotes SNCA/α-synuclein release and transfer via extracellular vesicles with a hybrid autophagosome-exosome-like phenotype. Autophagy 14 10.1080/15548627.2017.1395992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales R, Duran-Aniotz C, Castilla J, Estrada LD, Soto C. 2012. De novo induction of amyloid-β deposition in vivo. Mol. Psychiatry 17:1347–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan S, Guo JL, Changolkar L, Stieber A, McBride JD, et al. 2017. Pathological tau strains from human brains recapitulate the diversity of tauopathies in nontransgenic mouse brain. J. Neurosci 37:11406–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, et al. 2006. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314:130–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngolab J, Trinh I, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Florio J, et al. 2017. Brain-derived exosomes from dementia with Lewy bodies propagate α-synuclein pathology. Acta Neuropathol. Commun 5:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]