Abstract

Tobacco is legally permitted for adults, easily available, and the prevalence of smoking is high. Tobacco use is the largest preventable risk factor for human disease. To reduce smoking, many countries have introduced public policy to restrict the distribution of tobacco. The aim of this study was to analyse tobacco smoking and nicotine dependence in Central Vietnamese men around Hue and Da Nang cities. Nicotine dependence was measured using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score. The cohort contained total of 1822 Central Vietnamese men from Hue and Da Nang: 1453 smokers and 369 non-smokers. Individuals completed a questionnaire and factors such as smoking initiation, quitting behaviour, and success in quitting were also recorded. In the smoking group, the average amount of time in which the individual had smoked was 26.4 years. Average FTND value was 4.02, median was 4, the first quartile was 2, and the third quartile was 6. In all, 431 smokers (30%) had an FTND score of 6 or higher; an FTND score of this value is considered to equate to an individual having high nicotine dependence. Therefore, it could be noted that high nicotine dependence is very common in Central Vietnam. High nicotine dependence was significantly correlated with years of smoking. The longer the smoking period, the higher the FTND score. A high FTND score correlated with the individual being less likely to successfully quit smoking. The results of the questionnaire demonstrate that even when there is no restriction in public policy concerning the distribution of tobacco, individuals still wish to quit smoking. This study identified a high prevalence of severe nicotine dependence in Central Vietnamese men and the majority smokers wished to quit smoking. Consequently, the results of this study highlight the acute need for a specific programme to aid smokers in Central Vietnam to quit smoking.

Keywords: smoking, nicotine dependence, quitting of smoking, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI), Vietnam

Background

Tobacco smoking is recognised as being the main cause of premature death globally.1,2 The use of tobacco has declined significantly, but despite this smoking still causes more deaths than all the other major diseases combined. Tobacco use is the single largest preventable risk factor for diseases.3 As the use of tobacco is legal, the prevalence of tobacco smoking is still very high in most countries. Once the health risks of smoking were common knowledge, Western societies implemented restrictive policy which resulted in a drastic reduction in tobacco smoking. However, in developing countries, the tobacco epidemic is still in the growing phase.1,4 It has been estimated that tobacco smoking causes around 6 million deaths each year worldwide and 80% of these deaths are premature and hit lower income populations.4 Reducing the prevalence of smoking betters the health of the general population by avoiding premature disability and death. Thus, the easiest and most effective way to improve the quality of life of a population is to support individuals in quitting smoking.5,6

Some previous studies have analysed the prevalence of smoking in Vietnam and identified quite a distinctive pattern in the population. A large study analysing smoking prevalence in a Vietnamese cohort identified that 47.4% of men and only 1.4% of women were smokers.7 However, another study reported that the prevalence of ever-smoking was much higher, reporting that 74.9% of men and 2.6% of women were smokers.8 Thus, in Vietnam, smoking is almost exclusively prevalent in men. The most recent study replicated this prevalence and determined that 45.5% of men and 1.1% of women were smokers.7 This study also reported that despite the high prevalence of smoking, most of the smokers wanted to quit but they reported various difficulties in doing so. It also identified that most smokers have their first smoke of the day within 5 to 30 minutes after waking up.7 So far, no study has characterised nicotine dependence in the Central Vietnam population. The analysis of nicotine dependence in the Central Vietnam is important for the planning of health policy and for the analysis of the epidemiology of smoking-induced diseases. Central Vietnam is economically less developed as Northern or Southern Vietnam. Also, the environment of the Central Vietnam suffered more during the last wars. All these factors make local environment rather special compared with the northern and southern parts of the country. Therefore, for wider epidemiologic research programmes, nicotine dependence information of the region is necessary.

As nicotine dependence is the major driving force of reducing the success to quit smoking, the aim of this study was to analyse the prevalence of nicotine dependence in Central Vietnam that was defined by the population living in and around the Hue and Da Nang cities. The participants completed a questionnaire which generally described their smoking behaviour and then this was combined with their Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) score.9 The FTND was first developed in 1978 and adjusted following further studies.9-12 The FTND is one of the best self-reporting approaches for measuring nicotine dependence, using physiological and behavioural symptoms. The test is now considered the gold standard for population studies and is highly reliable.11 In addition to the FTND, Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) can also be used to measure nicotine dependence.13 This test consists of 2 parts: (1) the amount of time until the first cigarette of the day is smoked and (2) the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The HSI is a smaller-scale version of the FTND and the 2 complement each other very well.14 The advantage of HSI is its brevity that makes it a time-saving alternative to the FTND. We report a detailed comparison between these 2 methods.

In this study, a standard questionnaire was implemented which was later transformed into a Web-based database to enable large-scale future studies. A REDCap database platform was used to build an electronic data capture system which is now open to other parts of Vietnam and for international collaboration.15 We identify that nicotine dependence is high among Central Vietnamese men and highlight the fact that to reduce smoking, efficient quitting consulting is necessary.

Methods

Study design and participants

A community-based cross-sectional study was performed in 2015 in Da Nang and Hue, Central Vietnam. The initial plan was to collect 2000 participants with balanced age distribution to reduce the effect of potential confounders. The collection focused only on men due to the already demonstrated extremely low prevalence of smoking in Vietnamese women. All participants were more than 18 years of age. The Ethics Review Committees on Human Research of the University of Tartu, Da Nang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy, and Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy approved the protocols and informed consent forms used in this study. All participants signed a written informed consent form during the completion of the questionnaire.

Smoking data

Smokers were defined as any individual that had smoked for at least 1 year. This definition was applied because the primary goal was to analyse nicotine dependence that is a chronic and stable condition. Occasional smokers were excluded for the study and only people with some minimal regular smoking time were included. The questionnaire used in the study contained 19 questions, was in the Vietnamese language, and was designed to collect demographic information, smoking behaviour, and nicotine dependence. The collected data were then inputted into the Web-based database using the REDCap software, which is now available for any other future studies.15 REDCap is an abbreviation for the Research Electronic Data CAPture and is an innovative software to support clinical and translational research. REDCap is a workflow methodology for rapid development and deployment of electronic data capture which can be used in a clinical setting; therefore, it is an ideal platform for subsequent smoking studies.

The following questions were asked during data collection:

Year of birth;

Sex;

Ethnicity;

‘Have you ever smoked at least 1 year?’

‘Are you a current or former smoker?’

Age of starting smoking;

Age of stopping smoking;

Types of tobacco products;

The main cause of smoking;

‘How soon after waking up do you smoke your first tobacco?’

‘Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden?’

‘Which tobacco would you hate most to give up?’

‘How many cigarettes per day do you smoke?’

‘Do you smoke more frequently in the morning?’

‘Do you smoke even if you are sick in bed most of the day?’

‘Have you ever tried to quit smoking?’

‘For what reasons have you tried to quit smoking?’

‘Have you restarted smoking again?’

‘Why did you restart smoking again?’

The first questions were used to assess the smoking habits more generally. An individual was considered a smoker if they had smoked regularly for at least 1 year.16 This definition was introduced by Doll and Hill16 in their seminal paper, where they described the connection between smoking and lung cancer. This definition was used because it was easier to understand for participants and eliminated casual smokers with very little smoking activity. Questions 10 to 15 are part of the FTND. Responses to this section were converted to numerical values and a summary score out of 10 was generated. A score of 10 is the maximum value for the FTND and the scoring was based on the revised version of the test.11 The remaining questions described quitting behaviour and reasons for quitting (health, price, etc) and analysed different motivators to restart smoking. This design for the questionnaire meant that it was short, relatively easy to use, and is now inputted on the Web-based platform for convenient use via personal computers or mobile devices.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R studio. Packages plyr, dplyr, ggplot2, and corrgram were used. The analysis evaluated the smoking intensity, the years of smoking, FTND, quitting, and restarting smoking. Smoking behaviour was divided into 2 major categories: current smokers and never smokers. Responders were classified according to their age which was broken down into 6 groups: 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, and above 65. Smoking activity was divided into 4 categories: below 10, 11 to 20, 21 to 30, and more than 31 cigarettes per day (CPD). For group-wise comparisons, t test or analysis of variance was used. Heaviness of Smoking Index was also calculated.13 This index has been validated in other studies and it is has been shown to be comparable with the FTND.14,17 Literature supports that only in cases of low nicotine dependence, FTND performs better than HSI.18 We compared the performances of these tests in our study group in addition to analysing the correlation between nicotine dependence and quitting pattern.

Results

General smoking characteristics of the Central Vietnamese

An FTND was applied to study the smoking behaviour of the male population of Central Vietnam. Men were selected because it has previously been demonstrated that the prevalence of smoking is very low in Vietnamese women. Strickingly, the male smoking population has been reported to be extremely high, exceeding more than half of the male population.7 Data were collected from 1822 individuals, which broke down to 1453 smokers and 369 non-smokers (Table 1). In the smoking group, the average amount of time in which the individual had smoked for was 26.4 years, and on average, the age when the individual started smoking was 17 years old. Most of the participants smoked up to 10 (634 persons) or 11 to 20 (621 persons) CPD. However, other individuals smoked a considerable amount more. In all, 144 participants smoked 21 to 30 and 41 smoked more than 31 cigarettes a day. Most of the smoking group had attempted to give up smoking at least once.

Table 1.

Smoking characteristics by age group in the Central Vietnamese male cohort.

| Variable | Age group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | >65 | All | |

| n | n | n | n | n | n | n | |

| Total | 484 | 272 | 243 | 272 | 183 | 368 | 1822 |

| Smokers | 346 | 187 | 211 | 238 | 163 | 308 | 1453 |

| Age started smoking | 17 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| SD | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Cigarettes per day | |||||||

| Up to 10 | 208 | 89 | 90 | 73 | 65 | 109 | 634 |

| 11-20 | 118 | 84 | 91 | 112 | 74 | 142 | 621 |

| 21-30 | 9 | 12 | 25 | 38 | 20 | 40 | 144 |

| More than 31 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 15 | 41 |

| Quitting attempts | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| SD | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| FTND score | |||||||

| Mean | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| SD | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Low scorers | 286 | 143 | 149 | 143 | 112 | 182 | 1015 |

| High scorers | 58 | 43 | 61 | 93 | 51 | 125 | 431 |

| HSI score | |||||||

| Low | 304 | 154 | 173 | 165 | 128 | 231 | 1155 |

| High | 39 | 32 | 36 | 69 | 34 | 75 | 285 |

Abbreviations: FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; HSI, Heaviness of Smoking Index; SD, standard deviation.

Nicotine dependence in the study cohort

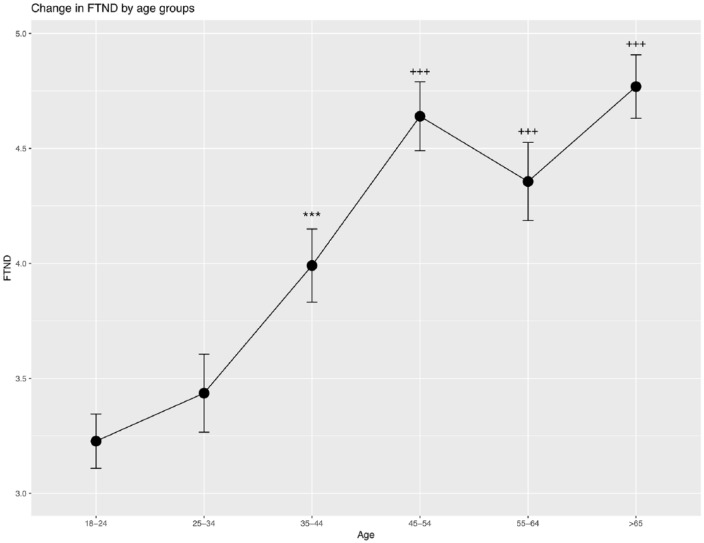

In the smoking cohort, the mean FTND score was 4.1 and the median was 4.0 (standard deviation was 2.4). The FTND increased with age and with the years of smoking (Table 1). Increased FTND correlated significantly with the years of smoking (P < 2.2E−16) and with the age at which the individual started smoking (P < 4.9E−7). The FTND score was significantly different between older and younger age groups and this difference increased with the age. Statistically significant differences emerged from the age group 35 to 44 and higher. The age-dependent increase in FTND is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Change in the FTND score related to the age group of participants. Average FTND scores are plotted in relation to the age groups. FTND indicates Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

***P < .001 compared with group 18 to 24; +++P < .001 compared with groups 18 to 24 and 25 to 34.

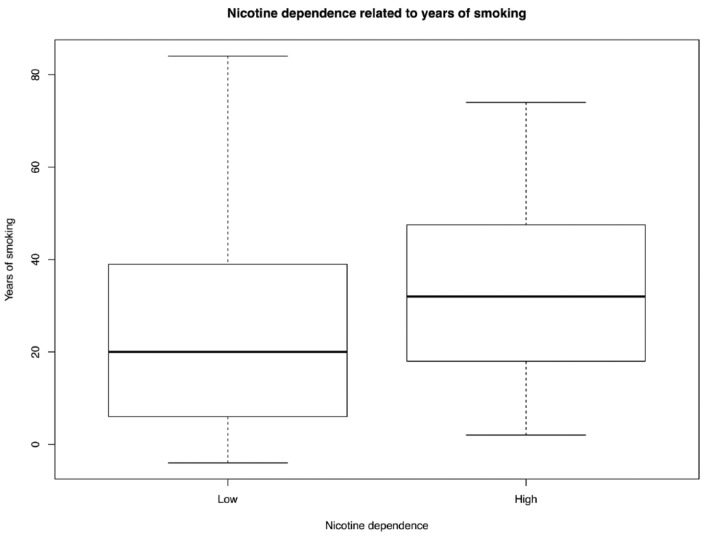

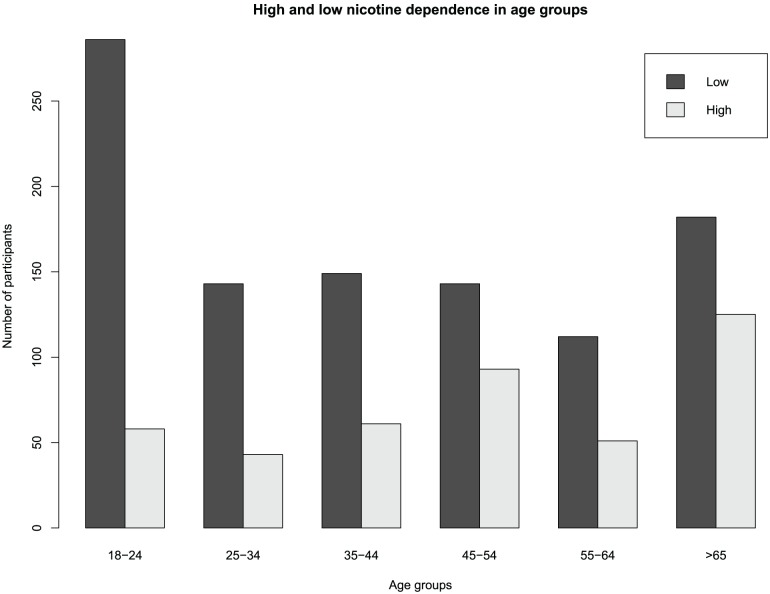

The age when an individual started smoking did not generally differ between age groups; however, we note that the youngest age group started smoking significantly earlier (mean age 17) than the older participants (starting age between 19 and 20). This indicates that the number of years of smoking is more important in the development of nicotine dependence rather than the age of starting. The critical age seems to be between 35 and 44 where FTND sharply increases and continues to increase in the next age group. In this age group, individuals have smoked for around 15 to 25 years. This indicates that the development of established nicotine addiction occurs after a longer period of smoking. To study this relation further, FTND scores were divided into 2 categories: ‘high’ and ‘low’. The ‘high’ FTND group (n = 431) contained all individuals who scored 6 or above in the FTND and the ‘low’ FTND (n = 1015) contained all individuals who had an FTND score below 6.14,17 Years of smoking differed significantly between ‘high’ and ‘low’ dependence (P = 4.9E−15). Smokers with ‘high’ dependence have smoked an average of 32 years, whereas smokers with low dependence have smoked on average 24 years (Figure 2). The rise of ‘high’ nicotine dependence related to the age group of participants is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The comparison of smoking years between participants with ‘high’ and ‘low’ nicotine dependence is illustrated.

Figure 3.

Distribution of ‘high’ and ‘low’ nicotine dependence in the study group. The increase in nicotine dependence correlates with an increase in age of smokers.

FTND and HSI correlation

The HSI has been suggested as an alternative to the FTND because it is shorter and simpler for completion. In many previous studies, good correlation between FTND and HSI has been found.13,14,17 In some studies, the reliability of HSI and correlation with the FTND were found to be less evident.18 This study found a high correlation between FTND, with the correlation coefficient being 0.89 (P = 2.2E−16). This is understandable because the HSI method uses 2 questions from the FTND. When smokers were divided into high (more than 4) and low (below 3) dependence based on HSI score, it was found that in the cohort there were 285 individuals with a high HSI score and 1155 with a low HSI score. Using the FTND score, 431 individuals were found to have high dependence (above 6) and 1015 with low (below 5) dependence. In this respect, HSI failed to identify nearly half of the more dependent individuals. Although the score is arbitrary, this result illustrates that these 2 scores are not entirely interrelated, and it is important to differentiate between them.

Patterns of smoking behaviour

During the data collection, the reasons to start smoking, for quitting smoking, and to restart smoking were also documented. The main reasons that participants gave for why they started smoking were ‘smoking facilitates communication’ and ‘tobacco craving’ and ‘smoking calms’.

To analyse the quitting attempts, the number of times participants tried to quit smoking and the reason to do so were also asked. Most smokers have tried to quit smoking 1 to 2 times (n = 577) or never (n = 546). There was a significant correlation between FTND score and the number of quitting attempts; thus, the higher the FTND score, the lower the number of attempts of quitting. Altogether, 887 participants had tried to quit smoking at least once, with the majority (745) attempting to quit for health reasons. This does not mean that all of the smokers who attempted to quit were sick, but they were concerned about their health and the detrimental effects of smoking.

Finally, the reasons to restart smoking were analysed. ‘Stress’ was named as the most frequent reason (n = 315). The next most common reasons were ‘other’ (n = 140) and ‘withdrawal symptoms’ (n = 112). Overall, people start smoking for social reasons (communication), they quit smoking because of health concerns, and then they restart smoking again because they feel stressed. This pattern is very broad, but still can describe the general aspects of smoking behaviour in our cohort.

Discussion

This study describes the smoking-related behaviour and nicotine dependence in Central Vietnamese men. Vietnam is a country where smoking and smoking advertising are not restricted at all or restrictions are very limited. Therefore, the smoking pattern and nicotine dependence have mostly been influenced by cultural and social values. The first interesting fact is that smoking is rare (around 1%) among women, which has been supported by many previous studies.8,19 This trend has been stable for several years and seems to be unchangeable even in conditions with little restrictions on smoking. The finding supports the idea that smoking initiation has, at least in some part, cultural influence that is quite stable. On the contrary, to women, smoking is very common among men and around 50% of men in Vietnam are smokers.8,19 As most of the women do not smoke in Vietnam and the goal was to study the nicotine dependence, only men were included in this study.

Nicotine dependence has multiple implications to the public health. First, nicotine dependence is a major force driving the urge of smoking and makes quitting very difficult.9,20 Second, nicotine dependence has a high co-morbidity with certain psychiatric diseases, such as mood disorders and substance abuse.21-23 Third, smoking is the most common risk factor for ill health, directly affecting the respiratory and cardiovascular systems and causing premature death.24,25 Therefore, nicotine dependence has several severe implications on public health and so evaluation of the prevalence helps to better understand its mechanism.

The main finding of this study was that nicotine dependence was highly prevalent in Vietnam, with around 30% of smokers having high nicotine dependence (431 versus 1015) that was defined by an FTND score of 6 and above. Nicotine dependence was not prevalent in younger individuals but there was a clear correlation with the age of smoking. The FTND increased sharply after more than 10 years of smoking (age group 35-44) and continued to grow in the older age groups. The FTND score for the 45 to 54 age group reached its maximum and remained constant. Although the average FTND was not high, from 3.4 to 4.0 and to 4.6 (Table 1), it was statistically significant. In addition, the percentage of individuals with ‘high’ dependence followed this pattern. Up to the age group 35 to 44, the high dependence was prevalent in around 30% of individuals, and after 45 to 54, ‘high’ dependence became more prevalent compared with smokers with ‘low’ dependence. This pattern demonstrates how important it is to stop smoking as early as possible, because in later years, the high nicotine dependence becomes more prevalent making quitting more difficult.

In this study, ‘high’ dependence was defined as an FTND score of 6 or above. This division is based on the most common approach found in literature, where a score of 6 defines ‘high’ nicotine dependence.14,17 Although other cut-offs (eg, 3 groups) have also been suggested, we deem a score 6 to be reasonable. However, we note that FTND is not a continuous measure for nicotine dependence and an even smaller value can still indicate the presence of nicotine dependence.

The FTND has been recognised as a good predictor for smoking cessation in previous studies.20,26 More precisely, smokers with an FTND score less than 4 are more likely to be successful at quitting smoking (26.5%) compared with smokers with a higher FTND score (8%).27 Therefore, the increase in FTND with the time of smoking is an important factor and indicates transformation from ‘mild’ to ‘high’ dependence.

The age at which individuals started smoking was relatively old and the main reason given for started smoking was ‘social communication’. In our study, mean smoking initiation age was 19 years. This is much later than in European countries but is similar to data from the Asian region.19 A recent large study involving 13 countries described the mean age for smoking initiation 19 years in Vietnam.19 This indicates that our data are comparable with existing international cohorts. Quitting smoking was motivated mainly by health concerns. This indicates that even in the societies where smoking is not restricted (smoking is allowed almost everywhere and in any time), the people are aware of the related health risks and are seriously concerned about this risk. In the background of high prevalence of smoking, this is good news and shows that there is good acceptance in the society to reduce smoking.

Interestingly, ever quitting smoking was not correlated with age. It seems that health conscious behaviour (despite no health problems) is the leading reason for quitting smoking attempts. This finding indicates again that in general the society in Vietnam is ready to reduce the prevalence of smoking and supportive measures for quitting will find good acceptance.

This study has several limitations. The first being that the study is based on information collected from Central Vietnam, so it is difficult to make nation-wide conclusions. However, during the study, a Web-based database was designed, and this database can also be accessed from other parts of the country, so it is easy to engage smokers from other regions for future studies. Second, this study did not analyse individual differences in the development of nicotine dependence. For additional analysis, the cohort should be genotyped of the known loci responsible for developing or modifying nicotine dependence.28,29 For instance, variations in CHRNA5 (cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 5 subunit) have been shown to influence nicotine dependence in Polish individuals.30,31 Genetic factors also influence the interaction between smoking and disease development.32,33 An individual’s genetic background is a convertible contributing factor for development of high dependence which consequently makes quitting smoking very difficult. In this study, genetic analysis was not performed, and the genetic background of the nicotine dependence was not analysed. And, third, as our study is based on self-reporting of smoking behaviour, several details are affected by the recalling quality and should be treated with a reservation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, to date, this study is the first characterisation of the prevalence of nicotine dependence in Central Vietnam. This study demonstrates that high nicotine dependence is very common in men from Central Vietnam and highlights the need for further analysis. The high nicotine dependence identified throughout the cohort through this analysis indicates that there is a demand for supportive counselling for quitting smoking. We foresee that these results could potentially reflect the situation in other countries in the Indochina region.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by institutional research grants IUT20-46 of the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, by the projects DIOXMED, EVMED from Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, by the H2020 ERA-chair grant (agreement 668989, project TransGeno).

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Note: Sulev Kõks is also affiliated with Institute number 5, Centre for Comparative Genomics, Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA, Australia.

Authors’ Contributions: GK performed the statistical analysis, arranged ethical approvals, prepared figures and drafted the manuscript; HDTT helped to collect samples and data; NBTN helped to collect samples and data; LNNH helped to collect samples and data; HMTT helped to collect samples and data; TCN helped to collect samples and data; TDP helped to collect samples and data; XDH helped to collect samples and data; BHD helped to collect samples and data; FL help to build the database; SK conceived the study, helped with data management and helped to finalize the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Sulev Kõks  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6087-6643

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6087-6643

References

- 1. WHO. MPOWER: A Policy Package to Reverse the Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Pruss-Ustun A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011: Warning About the Dangers of Tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ. 2000;321:323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Viet Nam 2010. Hanoi: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bui TV, Blizzard L, Luong KN, et al. Declining prevalence of tobacco smoking in Vietnam. Nicot Tobac Res. 2015;17:831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav. 1994;19:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12:159–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diaz FJ, Jane M, Salto E, et al. A brief measure of high nicotine dependence for busy clinicians and large epidemiological surveys. Aust New Zeal J Psychiat. 2005;39:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J. 1950;2:739–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chabrol H, Niezborala M, Chastan E, de Leon J. Comparison of the heavy smoking index and of the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence in a sample of 749 cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1474–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perez-Rios M, Santiago-Perez MI, Alonso B, Malvar A, Hervada X, de Leon J. Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence vs heavy smoking index in a general population survey. BMC Publ Health. 2009;9:493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giovino GA, Mirza SA, Samet JM, et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys. Lancet. 2012;380:668–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fagerstrom K, Russ C, Yu CR, Yunis C, Foulds J. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence as a predictor of smoking abstinence: a pooled analysis of varenicline clinical trial data. Nicot Tobac Res. 2012;14:1467–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2004;61:1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lind PA, Macgregor S, Vink JM, et al. A genomewide association study of nicotine and alcohol dependence in Australian and Dutch populations. Twin Res Hum Gene. 2010;13:10–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kõks G, Fischer K, Kõks S. Smoking-related general and cause-specific mortality in Estonia. BMC Publ Health. 2017;18:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thun MJ, Day-Lally CA, Calle EE, Flanders WD, Heath CW., Jr. Excess mortality among cigarette smokers: changes in a 20-year interval. Am J Publ Health. 1995;85:1223–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: comparison with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction. 2011;106:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breslau N, Johnson EO. Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Publ Health. 2000;90:1122–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang XY, Chen da C, Xiu MH, et al. Association of functional dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (DBH) 19 bp insertion/deletion polymorphism with smoking severity in male schizophrenic smokers. Schizophr Res. 2012;141:48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Z, Seneviratne C, Wang S, et al. Serotonin transporter and receptor genes significantly impact nicotine dependence through genetic interactions in both European American and African American smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;129:217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sieminska A, Jassem E, Kita-Milczarska K. Nicotine dependence in an isolated population of Kashubians from North Poland: a population survey. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buczkowski K, Sieminska A, Linkowska K, et al. Association between genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 locus and several nicotine dependence traits in Polish population: a case-control study. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:350348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang XY, Chen DC, Tan YL, et al. Smoking and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in male schizophrenia: a case-control study. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;60:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wojas-Krawczyk K, Krawczyk P, Biernacka B, et al. The polymorphism of the CHRNA5 gene and the strength of nicotine addiction in lung cancer and COPD patients. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]