Abstract

DYRK1A has been implicated as an important drug target in various therapeutic areas, including neurological disorders and oncology. DYRK1A has more recently been shown to be involved in pathways regulating human β-cell proliferation, thus making it a potential therapeutic target for both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Our group, using a high-throughput phenotypic screen, identified harmine that is able to induce β-cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo. Since harmine has suboptimal kinase selectivity, we sought to expand structure−activity relationships for harmine’s DYRK1A activity, to enhance selectivity, while retaining human β-cell proliferation capability. We carried out the optimization of the 1-position of harmine and synthesized 15 harmine analogues. Six compounds showed excellent DYRK1A inhibition with IC50 in the range of 49.5–264 nM. Two compounds, 2–2 and 2–8, exhibited excellent human β-cell proliferation at doses of 3–30 μM, and compound 2–2 showed improved kinase selectivity as compared to harmine.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinases (DYRKs) belong to the CMCG family of eukaryotic protein kinases. The DYRK family consists of five subtypes including 1A, 1B, 2, 3, and 4. Among them, DYRK1A is the most extensively studied subtype. It is ubiquitously expressed and has been shown to play an important roles in brain development and function,1 neurodegenerative diseases,2,3 tumorigenesis and apoptosis,4,5 and other cellular functions. More recently, DYRK1A has been shown to be involved in molecular pathways relevant to proliferation of human insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells, making it a potential molecular target for β-cell regeneration as a therapy to treat Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.6–9 DYRK1A inhibition has been proposed to drive pancreatic β-cell proliferation in part by inducing translocation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors into the nucleus, allowing access to promoters of genes that subsequently activate human β-cell proliferation.6,8

Because of the prominent role of DYRK1A in neuro-degenerative disease and cancer, numerous studies have attempted to identify DYRK1A inhibitor scaffolds.1,3–7,9,10 Several DYRK1A inhibitors, like harmine from natural sources, as well as from small molecule drug discovery programs, have been identified and characterized, including epigallocatechin (EGCG) and other flavan-3-ols,11,12 leucettines,13,14 quinalizarine,15 peltogynoids Acanilol A and B,16 benzocoumarins (dNBC),17 indolocarbazoles (staurosporine, rebeccamycin, and their analogues),18 INDY,19 DANDY,20 and FINDY,21 pyrazolidine-diones,22,23 amino-quinazolines,24 meriolins,25–27 pyridine and pyrazines,28 chromenoidoles,29 11H-indolo[3,2-c]quinoline-6-carboxylic acids,30 thiazolo[5,4-f]quinazolines (EHT 5372),31,32 CC-401,33 and 5-iodotubercidin.9,34 Among all the DYRK1A inhibitors, harmine and its analogues (β-carbolines) are the most commonly studied and remain the most potent and orally bioavailable class of inhibitors known to date.3,10 Historically, harmine is also known to exhibit hallucinogenic properties acting as a CNS stimulant, due to its affinity for the serotonin, tryptamine, and other receptors.35,36 Studies have revealed multiple CNS-based effects of harmine, including excitation, tremors, convulsion, and anxiety.37 Also, harmine and several related analogues have been found to inhibit DYRK1A-mediated phosphorylation of tau protein, thought to be relevant to Alzheimers’s disease (AD) and Down’s syndrome (DS, trisomy 21).38 Harmine has also attracted serious interest for cancer therapy.39–43 Using systematic structure modifications, several harmine analogues have been identified to show potent anti-proliferative tumor activity, in vitro and in vivo through multiple mechanisms of action, including inhibition of topoisomerase I,44,45 inhibition of CDKs,46 induction of cell apoptosis,47 and DNA intercalation.48

Recently, using a luciferase reporter phenotypic high-throughput small-molecule screen (HTS), our group identified harmine as a new class of compounds able to induce human β-cell proliferation, as measured by immunolabeling of insulin producing β-cells, in a range relevant for therapeutic human β-cell expansion.6 DYRK1A is the most likely target of harmine for β-cell proliferation, as demonstrated by genetic silencing, overexpression, and other studies, likely working through the nuclear factors of activated T-cells (NFAT) family of transcription factors that activate cell cycle machinery to cause proliferation while maintaining differentiation in the human β-cell.6 Using three different mouse, rat, and human islet−implant models, it was also shown that harmine is able to induce β-cell proliferation, increase islet mass, and improve glycemic control.6 Other laboratories have confirmed these results with other DYRK1A inhibitors unrelated to the harmine scaffold.7–9

DYRK1A and NFATs are widely expressed outside β-cells, and harmine analogues are known to have off-target effects, leading to pharmacological side effects, thereby limiting the therapeutic utility and potential for pharmaceutical development of harmine analogues for a chronic disease like diabetes. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop strategies to identify selective harmine analogues specifically designed to induce human β-cell proliferation as pharmacological probes for therapeutic development, with limited off-target activities. In addition, optimized selective harmine analogues may also be useful for specific, targeted delivery to the β-cell. One such prototype technology from DiMarchi and colleagues was recently developed to conjugate estrogen derivatives to GLP-1 analogue peptides to effectively target cells that express GLP1-receptor.49

With knowledge of this previous work, we explored the binding pockets of known DYRK1A inhibitor-co-crystal structures and identified areas for expansion of the harmine scaffold that will make new contacts to DYRK1A to identify kinase selective as well as linkable harmine analogues for targeted therapy. We carried out the optimization studies of harmine to expand the structure−activity relationships for harmine and to correlate DYRK1A activity, kinase selectivity, and human β-cell proliferation. Herein, we report the optimization of harmine 1-position and identification of harmine-based DYRK1A inhibitors that exhibit excellent human β-cell proliferation with improved kinase selectivity as compared to the hit molecule harmine.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry.

The 1-position harmine amine analogues were synthesized by the following reaction sequence outlined in Scheme 1. m-Anisidine underwent classical diazotization to form corresponding aryldiazonium salt which was coupled with 3-carboxy-2-piperidone to give arylhydrazone 1–2.50 Fisher indole cyclization of the resulting arylhydrazone in the presence of formic acid afforded 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1-oxo-β-carboline 1–3.50 Oxidation of 1–3 using DDQ followed by chlorination with phosphorus oxychloride generated 1-chloro-β-carboline 1–5 in 79% yield.51,52 Finally, 1-amino-β-carbolines 1–6 (10 analogues) were prepared via amination of 1-chloro precursors 1–5 by heating with an excess of neat amine at 170 °C in 43–87% yield.52 Analogue 1–6a was synthesized by Pd catalyzed amination of 1–553 (conversion for this amination was surprisingly low though provided a sufficient amount of pure compound for in vitro assay).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1-Amino Harmine Analoguesa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) NaNO2 (1.03 equiv), HCl, 10 °C, 1 h, (b) ethyl 2-oxopiperidine-3-carboxylate (1.05 equiv), KOH (1.2 equiv), pH adjusted to 4–5, water, rt, 5 h; (c) formic acid, reflux, 1 h; (d) DDQ (1.2 equiv), 1,4-dioxane, 0 °C-rt, 1 h, 23% (4 step); (e) POCl3, 150 °C, 24 h, 79%; (f) R1R2NH (10 equiv), 170 °C, 24 h, 43–87% (for 1–6b−1–6j); (g) Ruphos (1 mol %), RuPhos Precat (1 mol %), azetidine (1.2 equiv), LiHMDS (1 M in THF, 2.4 equiv), 90 °C, 96 h, 31% (based on 32 mg (64%) recovered starting material, for 1–6a).

1-Hydroxymethyl and 3-hydroxymethyl substituted β-carbolines were synthesized using the sequences shown in Scheme 2. Oxidation of harmine with m-CPBA generated the corresponding N-oxide 2–1, which subsequently underwent Boekelheide rearrangement in the presence of trifluoroacetic anhydride to give the desired 1-hydroxymethyl β-carboline 2–2 as a white solid in 49% yield.54,55 Alternatively, 6-methoxyindole was reacted with oxime 2–3, prepared from ethyl 3-bromo-2-oxopropanoate, in the presence of sodium carbonate at room temperature to give indole-oxime 2–4.56 Oxime reduction of 2–4 with zinc powder in acetic acid then provided tryptophanyl ester 2–5, which underwent Pictet-Spengler cyclization with acetaldehyde to provide 1-methyl-3-hydroxymethyl tetrahydro-β-carboline 2–6.56,57 Aromatization of compound 2–6 followed by reduction of the ester afforded the final compound 2–8 as white solid.57 Reduction of 2–8 using Et3SiH and PdCl2 as catalyst afforded 1,3-dimethyl-7-methoxy-β-carboline 2–9 as a white solid.58

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 1-Hydroxymethyl and 3-Hydroxymethyl Harmine Analoguesa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) m-CPBA (3 equiv), MeOH, CHCl3, 70 °C, 12 h, 47%; (b) TFA anhydride (2.5 equiv), CH2Cl2, reflux, o/n, 49%; (c) N2H4OH·HCl (1 equiv), MeOH, CHCl3, rt, 24 h, 81%; (d) 2–3 (1 equiv), K2CO3 (5.5 equiv), DCM, rt, 48 h, 34%; (e) Zn dust, AcOH, rt, o/n, 96%; (f) acetaldehyde (1 equiv), TFA (5%), DCM, rt, o/n; (g) S8 (2 equiv), xylene, reflux,o/n, 75%; (h) LiAlH4 (2 equiv), THF, rt, 12 h, 91%; (i) Et3SiH (16 equiv), PdCl2 (0.2 equiv), EtOH, 90 °C, 5 h, 27%.

Synthesis of 1-(1-hydroxy)ethyl and 1-acetyl harmine analogues are outlined in Scheme 3. 6-Methoxy tryptamine underwent Pictet-Spengler cyclization with pyruvic aldehyde in the presence of 5% TFA to provide 1-acetyl-7-methoxytetrahydro-β-carboline 3–1. Aromatization of compound 3–1 followed by reduction of the acetyl group afforded the 1-(1-hydroxyethyl) harmine analogue 3–3 as a white solid in 49% yield.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 1-(1-Hydroxy)ethyl and 1-Acetyl Harmine Analoguesa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) pyruvic aldehyde (1.2 equiv), TFA (5%), DCM, rt, 12 h; (ii) KMnO4 (4 equiv), THF, rt, 12 h, 16% (two steps); (b) NaBH4 (2 equiv), MeOH, rt, 12 h, 49%.

Structure−Activity Relationship Studies of Harmine Analogues.

Harmine is a type I DYRK1A inhibitor that binds to the ATP binding pocket and forms hydrogen bonding interaction with both the side chain of Lys188 and backbone of Leu241 (Figure 1A).19 Recently, the crystal structure of an ATP-competitive inhibitor DJM2005 bound to DYRK1A was also reported.59 These data showed classical binding to the ATP site with the inhibitor forming hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone of Leu241 along with water-mediated contacts with the side chains Lys188, Glu203, and the backbone of Asp307 (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the primary amino group of DJM2005 was also shown to form two additional hydrogen bonds with the side chains of Asn292 and DFG motif Asp307.59 Moreover, it was also observed that movement of Phe170 in the DYRK1A−DJM2005 complex, created another “induced-fit”pocket which is occupied by the chlorophenyl group (Figure 1C,D). In comparison, harmine binds in ATP-binding site without accessing this additional space occupied by DJM2005. Hence, we proposed rational modifications of the 1-position of harmine to access this pocket to identify new harmine based DYRK1A inhibitors with the potential to be chemically linked to GLP-1 agonists, for example, for β-cell targeted delivery. Modifications of the 1-position in harmine have been explored previously,52,60,61 but not in the context of diabetes and β-cell proliferation. A total of 15 harmine analogues were synthesized following the routes described in Schemes 1, 2, and 3. DYRK1A binding activity of these analogues was screened using FRET-based LanthaScreen binding assay (Life Technologies), initially at two concentrations: 1000 nM and 300 nM. Those compounds showing ≥50% inhibition at 300 nM were titrated using 10 serial 3-fold dilutions (in duplicate) for IC50 determination.

Figure 1.

Comparison of harmine and DJM2005 binding to DYRK1A. (A) Harmine binds in the ATP-binding pocket of DYRK1A making hydrogen bonding contacts (yellow dashed lines) with the side chain of Lys188 and the backbone of Leu241 (PDB 3ANR). (B) DJM2005 also interacts with the backbone of Leu241 and makes water-mediated contacts with the side chains Lys188, Glu203, and the backbone of Asp307. Additionally, the primary amino group interacts with the side chain of Asn292 and Asp307 (PDB 2WO6). (C, D) The movement of Phe 170 in the DJM2005 complex (D) creates a pocket (orange mesh) that is occupied by the chlorophenyl group of DJM2005. (E) Superposition of the harmine (green) and DJM2005 (pink) complexes, highlighting the equivalent hydrogen bonding interactions with Leu241 and Lys188. Orientation is rotated 90 deg with respect to the view in panels C and D.

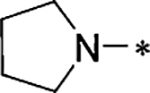

On the basis of our computational modeling, we investigated the effects of cycloalkylamines at the 1-position of harmine on DYRK1A binding. First, we studied three analogues with azetidine (1–6a), pyrrolidine (1–6b), and piperidine (1–6c) substituents at the 1-position. Compound 1–6a showed the best activity with IC50 of 159 nM. However, this compound was 5-fold less active than harmine. Increasing the ring size to five-membered (pyrrolidine, 1–6b) and six-membered (piperidine, 1–6c) ring reduced the DYRK1A inhibitory activity, with DYRK1A IC50 of 264 nM and 1500 nM, respectively. We also synthesized seven analogues from commercially available building blocks bearing substituents on the pyrrolidine at harmine 1-position to interrogate the induced binding pocket implicated by the structure of DJM2005 complex. As predicted, the substitution pattern on the pyrrolidine ring was very sensitive to the DYRK1A inhibition activity. Among these analogues, 1–6d and 1–6f showed modest DYRK1A inhibition activity. 2-Substituted pyrrolidine analogues were more potent inhibitors as compared to their 3-substituted analogues. Compound 1–6d with 2-phenyl pyrrolidine substituent showed a DYRK1A IC50 of 123 nM comparable to 1–6a (azetidine), and a 2-fold improvement over the corresponding analogue 1–6b. Unfortunately, introduction of a 3-chloro group, analogous to DJM2005, on 2-phenyl of the pyrrolidine 1-harmine analogue was detrimental for the activity (compound 1–6i, 22% inhibition at 300 nM.), thus demonstrating that harmine-based analogues with directly attached 1-position cycloalkyamines are unable to productively access the induced fit pocket of DJM2005.

Simple replacement of the harmine 1-methyl group with a chlorine atom (1–5) significantly improved the DYRK1A inhibition by 3-fold compared to harmine with IC50 of 8.81 nM (reported in the literature IC50 56 nM).60 We also investigated the effect of introducing polar groups such as hydroxyl, hydroxymethyl, and acetyl at the 1-position of harmine. Replacing 1-methyl with a hydroxyl substituent (or its pyridone tautomer) dramatically reduced the DYRK1A inhibition, rendering the compound inactive, unlike the Cl-subsitutent.

Interestingly, in contrast to a directly attatched hydroxyl group, introduction of 1-hydroxymethyl group (2–2) showed potent DYRK1A inhibition with IC50 of 55 nM (reported in lietrature IC50 106 nM),60 comparable but slightly less potent than harmine and a 2-fold improvement over 1-(2-phenyl-pyrrolidin-1-yl) harmine analogue 1–6d. We studied the binding pose of this compound to DYRK1A by induced fit docking and observed that it adopts a new binding pose that is distinct from the classical ATP-binding pose for harmine (Figure 1A). On the basis of the induced fit modeling, the 1-hydroxymethyl substituent causes the core scaffold to horizontally flip by 180°, creating the possibility for the hydroxyl group to form two new hydrogen bonding interactions with the side chain of Glu203 and the backbone of Phe308 while maintaining the canonical hydrogen bonding interactions with Leu241 and Lys188 (Figure 2A). In order to retain this new hydrogen bond interaction while maintaining the canonical binding pose of harmine, a “non-flipped” version of compound 2–2 with a hydroxymethyl group at the 3-position of harmine (compound 2–8) was synthesized as shown in the (Figure 2B). Induced fit docking of compound 2–8 predicted that repositioning of the hydroxymethyl group to the 3-position would cause it to revert to the canonical harmine binding mode. We were gratified to learn that 3-hydroxymethyl substituted analogue 2–8 showed IC50 of 49.5 nM, comparable to compound 2–2. Removal of the hydroxyl group (3-methyl carboline analogue 2–9, R = H) caused a significant decrease in the DYRK1A binding affinity with an IC50 = 971 nM. These data indicate the importance of the hydroxyl group in 2–8, further corroborating our modeling results.

Figure 2.

Binding model of 1-hydroxymethyl harmine analogues to DYRK1A. (A) Induced fit docking of compound 2–2 predicts that it adopts a binding mode that is distinct from harmine (see Figure 1A). The model shows that the hydroxymethyl group at the 1-position causes the scaffold to flip 180° horizontally, enabling new putative contacts with the side chains of Glu203 and Phe308, inaccessible to harmine. The model also shows retention of the original hydrogen bonds of harmine 2-nitrogen with Lys188 and 7-methoxy oxygen with Leu241, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines (PDB 3ANR). (B) Induced fit docking of compound 2–8 predicts that repositioning of the hydroxymethyl group to position-3 causes this compound to revert to the canonical harmine ATP-site binding mode, while creating new contacts from the 3-hydroxymethyl group with Glu203 and Phe308 proposed for the “flipped” binding mode for 2–2 (PDB 3ANR).

Introduction of an alpha methyl group to the 1-hydroxymethyl substituent of harmine 3–3 led to a complete loss of DYRK1A binding activity at the screening concentration, while the planar 1-acetyl substituted analogue (3–2) had an IC50 (66.7 nM) similar to compounds 2–2 and 2–8. This indicates that the 1-hydroxymethyl group of 2–2 occupies constrained space that does not accommodate further steric bulk, a possibility to have the binding mode similar to either 2–2 or 2–8.

Human β-Cell Proliferation Assay.

Eight compounds, 1–5, 1–6a, 1–6b, 1–6d, 1–6f, 2–2, 2–8, and 3–2, which showed DYRK1A inhibition IC50 < 250 nM, were assessed for their ability to induce human β-cell proliferation in vitro. Among these harmine analogues, compounds 2–2, 2–8, and 1–5 exhibited human β-cell proliferation at 10 μM comparable to that of harmine, as measured by Ki-67 immunolabeling (Figure 3A). A representative example of Ki-67 and insulin double positive cells induced by analogue 2–8 is shown in Figure 3B as per our literature protocols.6 Compound 3–2 with acetyl substituent at the harmine 1-position, despite having an IC50 comparable to 2–2 and 2–8, showed reduced β-cell proliferation at 10 μM. However, when the compound was tested at a higher concentration of 30 μM, proliferation in the range comparable to harmine was observed. Both the compounds 2–2 and 2–8 caused proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3C,D) with compound 2–8 showing superior human β-cell proliferation at a lower dose as compared to 2–2. Unlike harmine, which causes beta cell toxicity at doses higher than 10 μM, compound 2–2 and 2–8 did not cause toxicity even at 30 μM. Compounds 2–2 and 2–8 also drove NFAT2 translocation in a rat cell line that transiently transduced NFAT-GFP fusion genes to nucleus as observed for harmine. Collectively, these observations indicate that these compounds drive β-cell proliferation qualitatively like harmine, by inducing translocation of NFATs to the nucleus, likely allowing access to promoters of genes that subsequently drive human β-cell proliferation (Figure 3E,F).

Figure 3.

Effects of harmine analogues on human beta cell proliferation. (A) Initial screening of harmine analogues on human beta cell proliferation at 10 μM. DMSO was used as negative control, and harmine was used as positive control (n = 4–5). (B) A representative example from A of a Ki-67 and insulin double positive cells induced by analogue 2–8. (C) and (D) Dose−response curves for 2–2 and 2–8 in human β cells (n = 4 for each dose, harmine concentration 10 μM). (E) Quantification of nuclear frequency of NFATC1-GFP in R7T1 rodent beta cell lines treated with harmine, 2–2 and 2–8 (10 μM, 24 h; n = 3 for each compound). (F) A representative example of 2–8 (10 μM, 24 h) increasing the nuclear frequency of NFATC1-GFP in R7T1 rodent beta cells. In all relevant panels, error bars indicate SEM and, * indicates P < 0.05. A minimum of 1000 beta cells was counted for each graph.

Interestingly, except for 1–6a, the 1-amino substituted harmine analogues 1–6b, 1–6d, and 1–6f did not show any β-cell proliferation despite showing DYRK1A inhibition <270 nM, which may indicate a DYRK1A potency threshold for β-cell proliferation. An alternate rationale may be that some of the compounds with reduced β-cell proliferation, such as 1–5 and 1–6a, may have activity on anti-proliferative kinases in addition to DYRK1A that limit their β-cell proliferative capability. Furthermore, we also may suggest that the difference between in vitro DYRK1A binding and the human beta cell proliferation assay might be attributed to physicochemical properties, such as cell permeability and other physical chemical properties of the 1–6 harmine analogues. Studies to address these rationales are ongoing.

Kinome Scan Profile.

As previously mentioned, harmine is known to exhibit varying degrees of inhibition for kinases other than DYRK1A. In order to understand kinase selectivity, we carried out a kinome profiling of compound 2–2, 2–8, and harmine on 468 kinases at 10 μM concentration (Table 2, more potent activities <20% remaining colored as shown). Harmine inhibited 17 kinases (<20% activity remaining) in addition to DYRK1A at a screening concentration of 10 μM similar to earlier reports. Compound 2–2 exhibited a cleaner kinome profile as compared to harmine with significantly reduced inhibition against DYRK1B, CSNK1G2, CSNK2A1, HIPK2, HIPK3, IRAK1, IRAK3, and VPS3 at 10 μM. Additionally, in comparison to harmine, it showed affinity greater than harmine to only PIK4CB at the screening concentration (3.7 vs 19% activity remaining for 2–2 and harmine, respectively; see Supporting Information for complete Discoverx screening data). Interestingly, the kinome profile observed for compound 2–8 was much less selective than that of both harmine and 2–2. In addition to the kinases for which harmine and 2–2 showed inhibition, compound 2–8 exhibited inhibition of several additional kinases including CDKs, DAPKs, and PIMs (<20% activity remaining). Despite having poor kinome selectivity profile, it is interesting to note that compound 2–8 showed β-cell proliferation activity and DYRK1A inhibition comparable to harmine and 2–2. One probable explanation could be that some of these kinases have a compensatory mechanism to either induce or inhibit β-cell proliferation. The kinome profile data indicate that between the two harmine scaffold analogues 2–2 and 2–8, which have similar β-cell proliferation activity and DYRK1A binding, compound 2–2 has improved kinase selectivity, thus making it the lead compound for further studies.

Table 2.

Kinome Scan of Compound 2-2, 2-8, and Harminea

| Target |  |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–2 | 2–8 | Harmine | |||

| CDK11 | 98 | 4.8 | 83 | ||

| CDK7 | 27 | 0.65 | 21 | ||

| CDK8 | 94 | 0 | 55 | ||

| CDKL5 | 100 | 6.1 | 100 | ||

| CIT | 44 | 8.1 | 29 | ||

| CLK1 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 0.35 | ||

| CLK2 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 | ||

| CLK4 | 17 | 5 | 13 | ||

| CSNK1A1 | 10 | 7.8 | 15 | ||

| CSNK1D | 17 | 8 | 13 | ||

| CSNK1E | 6.5 | 1 | 1.7 | ||

| CSNK1G2 | 30 | 18 | 19 | ||

| CSNK2A1 | 34 | 8.3 | 11 | ||

| CSNK2A2 | 37 | 2.3 | 23 | ||

| DAPK1 | 85 | 8.8 | 78 | ||

| DAPK2 | 80 | 2.8 | 72 | ≤10 | |

| DAPK3 | 81 | 1.4 | 69 | 11≤20 | |

| DRAK2 | 88 | 11 | 73 | ||

| DYRK1A | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| DYRK1B | 66 | 0.35 | 6.1 | ||

| DYRK2 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 3.2 | ||

| HASPIN | 4.8 | 0.75 | 2 | ||

| HIPK1 | 30 | 2.7 | 21 | ||

| HIPK2 | 30 | 1.3 | 8.6 | ||

| HIPK3 | 21 | 2.1 | 9.4 | ||

| IRAK1 | 32 | 18 | 17 | ||

| IRAK3 | 39 | 70 | 15 | ||

| PIK4CB | 3.7 | 19 | 12 | ||

| PIM1 | 65 | 19 | 45 | ||

| PIM2 | 58 | 4.7 | 39 | ||

| PIP5K2C | 28 | 5 | 36 | ||

| RPS6KA4(Kin.Dom.2-C-terminal) | 54 | 1 | 40 | ||

| TGFBR2 | 91 | 17 | 78 | ||

| VPS34 | 53 | 28 | 13 |

Compounds were screened 10 μM against 468 kinases using Discoverx Kinome Scan. Results for primary screen binding interactions are reported as “% DMSO Control”, where lower values indicate stronger affinity (see the Supporting Information for details).

CONCLUSIONS

We have reported the structure−activity relationships of DYRK1A inhibition and β-cell proliferation for new harmine analogues using an integrated, structure-based drug design, computational modeling, and medicinal chemistry optimization approach. In order to access the putative induced binding pocket occupied by DJM2005, we synthesized several 1-amino harmine analogues (1–6a to 1–6j) to investigate their effect on DYRK1A kinase binding and human β-cell proliferation. Most of the 2-amino harmine compounds showed reduced DYRK1A inhibition activity at the screening concentration of 1 μM with the exceptions of harmine analogues 1–6a, 1–6b, and 1–6d. These analogues showed a range of 5–9-fold reduced DYRK1A inhibitory activity as compared to harmine, indicating that harmine-based analogues with cycloalkylamines directly attached at the 1-position are unable to productively access the induced fit pocket of DJM2005, suggesting alternate linking groups need to be explored.

In contrast, we have shown that harmine analogues 2–2, 2–8, and 3–2 bearing small polar groups like hydroxymethyl or acetyl exhibited potent DYRK1A inhibition with IC50 in the range of 49–67 nM, 2-fold more active than 1-azetidine harmine analogue 1–6b. However, introduction of the directly attached 1-hydroxy substituent (or its pyridone tautomer) was detrimental for DYRK1A inhibition. Interestingly among all the harmine analogues synthesized, the 1-chloro substituted harmine analogue (1–5) significantly improved DYRK1A inhibition and was the most potent DYRK1A inhibitor compound, with an IC50 of 8.8 nM, though it was not explored further as a lead due to its potential for nucleophilic substitution. Among the eight compounds with IC50 < 250 nM against DYRK1A (1–5, 1–6a, 1–6b, 1–6d, 1–6f, 2–2, 2–8 3–2), only 1–5, 2–2, 2–8, and 3–2 exhibited human β-cell proliferation comparable to that of harmine at similar or reduced concentrations. Importantly, harmine analogues 2–2 and 2–8 were most effective for inducing human β-cell proliferation in vitro, indicating that introduction of polar groups like hydroxymethyl at 1- and 3-positions of harmine improves the β-cell proliferation, possibly by improving kinase selectivity, as shown for 2–2. None of the 1-amino harmine analogues caused any β-cell proliferation. Kinome scan of 468 kinases for compounds 2–2 and 2–8 indicated that compound 2–2 exhibits a cleaner kinome profile as compared to harmine and 2–8 at a concentration of 10 μM. In contrast, compound 2–8 exhibited a much lower kinase selectivity, inhibiting several additional kinases including CDKs, DAPKs, and PIMs (<20% activity remaining). These data indicate the potential for improvement of the harmine scaffold for kinase selectivity, resulting in β-cell proliferation at lower concentration in vitro, with the potential for a cleaner off-target profile. We have been able to successfully modify harmine to identify a novel kinase selective DYRK1A inhibitor 2–2 with improved kinase selectivity and β-cell proliferation ability. These observations suggest that further improvements in DYRK1A binding affinity as well pharmacological studies in addition to DYRK1A binding of the harmine analogue series is an attractive approach to the development of effective and novel diabetes therapeutics for β-cell proliferation. The results of our ongoing structure-based drug design, medicinal chemistry SAR, and pharmacological studies will be reported in due course.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods.

1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker DRX-600 spectrometer at 600 MHz for 1H and 150 MHz for 13C. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica coated aluminum sheets (thickness 200 μm) or alumina coated (thickness 200 μm) aluminum sheets supplied by Sorbent Technologies, and column chromatography was carried out on Teledyne ISCO combiflash equipped with a variable wavelength detector and a fraction collector using a RediSep Rf high performance silica flash columns by Teledyne ISCO. LCMS/HPLC analysis for purity determination and HRMS was conducted on an Agilent Technologies G1969A high-resolution API-TOF mass spectrometer attached to an Agilent Technologies 1200 HPLC system. Samples were ionized by electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive mode. Chromatography was performed on a 2.1 × 150 mm Zorbax 300SB-C18 5-μm column with water containing 0.1% formic acid as solvent A and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid as solvent B at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The gradient program was as follows: 1% B (0–1 min), 1–99% B (1–4 min), and 99% B (4–8 min). The temperature of the column was held at 50 °C for the entire analysis. The purity of all the compounds was ≥95%. The chemicals and reagents were purchased from Aldrich Co., Alfa Aesar, Enamine, TCI USA. All solvents were purchased in anhydrous from Acros Organics and used without further purification.

Molecular Modeling.

All molecular modeling procedures were carried with the small-molecule drug discovery suite of Schrödinger LLC, release 2016–3. The Induced Fit Docking62 (IFD) protocol combining Glide and Prime was used to dock the compounds using the crystal structure of DYRK1A/harmine complex59 (PDB 3ANR) as a starting point. The IFD protocol modifies both the ligand and protein conformations to account for receptor flexibility. Within this protocol the protein−ligand complex conformations are ranked using the IFDScore, which is an empirical scoring function that combines Prime_Energy (the energy of the protein conformation), GlideScore (an approximation of the ligand binding free energy), and Glide_Ecoul (Coulombic interaction energy).62 While no explicit water molecules are included in our starting model due to the uncertainty in positioning these molecules, GlideScore does include solvation terms that simulate the effects of solvent.63 Glide docks explicit water molecules into the binding site for each energetically favorable ligand pose and employs empirical scoring terms that measure the exposure of various groups to the explicit waters. This explicit approach overcomes some of the limitations of continuum solvation models, particularly in the highly constrained environment of a binding site containing a bound ligand. Ligands and receptor were prepared using LigPrep and the Protein Preparation Wizard.64 MM/GBSA binging energy calculations were carried out with Prime MM-GBSA using the VSGB 2.0 solvation model.65 Figures were prepared using PyMOL 2.0 (Schrödinger, LLC).

DYRK1A Binding Assays.

Compounds were tested for DYRK1A binding activity by a commercial kinase profiling services, Life Technologies, which uses the FRET-based LanthaScreen Eu kinase binding assay.66 Compounds were screened for DYRK1A activity at concentrations of 1000 nM and 300 nM in duplicates. The IC50 was determined by 10 point LanthaScreen Eu kinase binding assay66 in duplicates.

B-cell Proliferation Assay.

Human pancreatic islets were obtained from the NIH/NIDDK-supported Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) (https://iidp.coh.org). Islets were first dispersed with Accutase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) onto coverslips as described earlier.6 Dispersed islets were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or with harmine-related compounds in RPMI1640 complete medium for 96 h. Then the cells were fixed and stained for insulin and Ki67.6 Total insulin positive cells and cells double positive Ki67 and insulin positive cells were imaged and counted. Islets from 3 to 5 different adult donors were tested as described in Figure 3, and at least 1000 beta cells were counted for each human islet donor.

NFAT2 Translocation Assay.

The immortalized R7T1 rat beta cell line was infected with an adenovirus expressing NFAT2-GFP6 for 48 h, and then the cells were treated with different compounds at 10 μM for another 24 h. The cells were imaged and counted for the NFAT2-GFP nuclear translocation. At least 1000 cells were counted.

Kinome Scan Profile.

Compounds were screened against 468 kinases at single concentration of 10 μM in duplicates at DiscoverX using their proprietary KINOMEscan Assay.67 The results for primary screen binding interactions are reported as ′% DMSO Ctrl′, where lower values indicate stronger affinity.

Synthetic Procedures.

7-Methoxy-2,9-dihydro-β-carbolin-1one (1–4).

m-Anisidine (1.096 mL, 38.56 mmol) was dissolved in 15 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid, and after cooling 15 mL of water was added to the solution. Sodium nitrite (2.74 g, 39.71 mmol) in 15 mL of water was added dropwise to the cold suspension and stirred for 1 h while maintaining the temperature below 10 °C. This solution was added to a cold solution of ethyl 3-carboxy-2-piperidone (7.0 g, 40.88 mmol) and potassium hydroxide (2.63 g, 47.01 mmol) in 20 mL of water which had been kept overnight at room temperature. The pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 4–5 by saturated aqueous solution of sodium acetate. The resultant mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h. The yellow solid was filtered and washed with a small amount of water and ethanol to give 6methoxyphenylhydrazone 1–2, which was immediately taken to the next step. The phenylhydrazone 1–2 was refluxed in 25 mL of formic acid for 1 h. The solution was neutralized with saturated aqueous solution of sodium carbonate and extracted with 100 mL of ethyl acetate three times. The organic layer was collected, dried over magnesium sulfate, and filtered, and the solvent was rotary evaporated to give the desired tetrahydro-oxo-β-carboline 2–3. To a solution of compound 1–3 in 60 mL of 1,4-dioxane was added DDQ (2.65 g, 11.7 mmol) in 40 mL of 1,4-dioxane dropwise at 0 °C and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. Upon completion of the reaction, 100 mL of water was added to the reaction. The product mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel and extracted with ethyl acetate (100 mL × 3) three times. The organic layer was washed with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide solution (50 mL × 3). The combined organic layer was then dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to provide the desired 7-methoxy-2,9-dihydro-β-carbolin-1-one 1–4 (1.91 g, 23% in four steps) as yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.85 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.12 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.06–7.08 (m, 2H), 6.86 (d, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.89 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.40, 155.72, 140.74, 127.75, 125.12, 122.58, 116.40, 110.78, 99.85, 94.69, 55.61; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C12H11N2O2+: 215.0815, found: 215.0806.

1-Chloro-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–5).

A solution of 7-methoxy-2,9-dihydro-β-carbolin-1-one (1.80 g, 8.49 mmol) in POCl3 (20 mL) was stirred at 150 °C for 24 h. The mixture was neutralized with the saturated aqueous solution of sodium carbonate. The solution was transferred to separatory funnel and extracted with ethyl acetate (50 mL × 3). The organic layer was collected, dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to provide the desired 1-chloro-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline 1–5 (1.56 g, 79%) as yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.19 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.96 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.78 (s, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.0 (s, 1H), 6.95 (m, 1H), 3.93 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ161.14, 142.87, 138.10, 132.93, 132.83, 130.73, 123.44, 115.06, 114.39, 110.60, 95.28, 55.78; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C12H10ClN2O+: 233.0476, found: 233.0471. Purity >95%.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 1-Amino-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6).

A solution of 1-chloro-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1 mmol) and amine (10 mmol) in a sealed pressure vessel was heated to 170 °C for 24 h. Upon the completion of the reaction monitored by LCMS, the reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by flash column chromatography using DCM/MeOH as eluent to afford the desired 1-amino-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline 1–6 as white solid.

1-(Azetidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6a).53

A screwcap pressure vessel, equipped with a magnetic stir bar, was charged with 1–5 (50 mg, 0.21 mmol) RuPhos (1 mg, 1 mol %) and RuPhos precatalyst (P1) (1.75 mg, 1 mol %). The vial was evacuated and backfilled with argon, and sealed with a Teflon screw cap. LiHMDS (1 M in THF, 2.4 equiv) was added via syringe, followed by azetidine (0.25 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 96 h. Conversion for the reaction was low. The solution was allowed to cool to room temperature, and then quenched by the addition of 1 M HCl (1 mL), diluted with EtOAc and poured into sat. NaHCO3. After being extracted with EtOAc, the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, then concentrated and purified by flash column chromatography using MeOH/DCM (10/90) as eluent to afford compound 1–6a (6.5 mg, 31% based on 32 mg (64%), recovered starting material) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.98 (m, 1H), 7.90 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.30 (m,1 H), 6.94 (m,1 H), 6.89 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.38 (t, 4 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.90 (s, H), 2.52 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 159.83, 149.05, 141.87, 136.84, 128.30, 123.52, 122.33, 115.48, 109.56, 106.39, 95.22, 55.61, 51.82, 17.42; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C15H16N3O+: 254.1288, found: 254.1284; purity > 95%.

1-(Pyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6b).

White solid. Yield 64%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.32 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.89 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.22 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 6.93 (s, H), 6.88 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 3.90 (m, 7H), 2.07 (s, 4 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 159.64, 146.72, 141.52, 136.88, 128.60, 123.63, 122.09, 115.48, 109.43, 104.82, 95.28, 55.58, 48.39, 25.35; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C16H18N3O+: 268.1444, found: 268.1460; purity > 95%.

1-(Piperidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6c).

White solid. Yield 87%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.05 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.90 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.48 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.90 (m, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.48 (broad s, 4H), 1.84 (broad s, 4H), 1.70 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.98, 149.23, 141.74, 136.57, 129.05, 126.62, 122.33, 115.66, 109.43, 108.75, 95.20, 55.60, 49.92, 26.09, 24.82; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C17H20N3O+: 282.1601, found: 282.1590; purity > 95%.

1-(2-Phenylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6d).

Brown solid. Yield 80%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.98 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.82 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.44 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.34 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.24 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 6.79 (m, 1H), 6.49 (d, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz), 5.48 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.06 (m, 1H), 4.01 (m, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3 H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 2.04 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 159.75, 146.24, 145.92, 141.60, 136.78, 128.85, 128.39, 126.45, 126.28, 124.43, 122.15, 115.49, 109.43, 105.63, 95.25, 61.35, 55.62, 50.48, 24.53; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H22N3O+: 344.1757, found: 344.1761; purity > 95%.

1-(3-Phenylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6e).

Brown solid. Yield 59%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.17 (s, 1H), 7.98 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 7.91 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.37 (m, 4H), 7.27 (m, 2H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 6.88 (d, 2H, J = 9 Hz), 4.33 (t, (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.09 (m, 1H), 4.01 (m, 1H), 3.94 (t, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.60 (m, 1H), 2.49 (m, 1H), 2.24 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ161.19, 143.50, 141.54, 139.47, 130.03, 128.60, 126.97, 121.83, 114.64, 112.61, 104.69, 95.30, 55.53, 50.12, 43.47, 32.24; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H22N3O+: 344.1757, found: 344.1750; purity > 95%.

1-(2-Benzylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6f).

Brown solid. Yield 65%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.05 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.91 (d, 2H, J = 9 Hz), 7.28 (m, 5H), 6.88 (m, 2H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.90 (m, 5H), 3.22 (m,1H), 2.79 (m, 1H), 1.97 (m, 3H), 1.84 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ160.66, 142.04, 138.44, 129.63, 128.26, 126.31, 121.94, 115.48, 110.80, 105.33, 94.95, 60.45, 55.54, 50.04, 39.36, 29.77, 23.65; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C23H24N3O+: 358.1914, found: 358.1900; purity > 95%.

1-(3-Benzylpyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6g).

Brown solid. Yield 71%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.14 (s, 1H), 7.96 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.90 (d, 2H, J = 9 Hz), 7.32 (m, 2H), 7.25 (m, 4H), 6.93 (s,1H), 6.87 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 4.01 (m, 2H), 3.90 (m, 4H), 1.08 (t, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 2.87 (m, 1H), 2.81 (m, 1H), 2.69 (m,1H), 2.17 (m, 1H), 1.83 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.62, 146.71, 141.52, 141.15, 137.03, 129.15, 128.76, 126.38, 123.56, 122.08, 115.49, 109.41, 104.81, 95.29, 55.58, 53.80, 47.95, 31.18; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C23H24N3O+: 358.1914, found: 358.1901; purity >95%.

1-(2-(2-Chlorophenyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6h).

Yellow solid. Yield 77%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.98 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.83 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.52 (m, 3H), 7.25 (m, 3H), 6.80 (m, 1H), 6.59 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 5.80 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.10 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3 H), 2.54 (m, 1H), 2.04 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.82, 145.77, 142.92, 141.72, 136.88, 131.91, 129.73, 129.08, 128.20, 127.30, 124.39, 122.17, 115.53, 109.47, 105.73, 95.33, 59.41, 55.62, 50.31, 32.65, 24.60; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H21ClN3O+: 378.1368, found: 378.1366; purity >95%.

1-(2-(3-Chlorophenyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6i).

Yellow solid. Yield 68%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.96 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.86 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.37 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.33 (t, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.28 (m, 2H), 6.83 (m, 1H), 6.65 (m, 1H), 5.51 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.07 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 2.04 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.84, 148.77, 146.08, 141.72, 136.73, 133.18, 130.33, 129.03, 126.48, 125.14, 122.20, 115.53, 109.51, 105.94, 95.30, 61.51, 55.62, 50.60, 35.23, 24.75; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H21ClN3O+: 378.1368, found: 378.1377; purity >95%.

1-(2-(4-Chlorophenyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (1–6j).

Yellow solid. Yield 43%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.97 (d, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 7.84 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.38 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.27 (m, 1H), 6.83 (m, 1H), 6.64 (m, 1H), 5.50 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.06 (m, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.47 (m, 1H), 2.04 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.80, 146.08, 144.98, 141.66, 136.78, 130.85, 128.95, 128.33, 124.47, 122.16, 115.51, 109.46, 105.81, 95.28, 60.99, 55.61, 50.49, 35.26, 24.63; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C22H21ClN3O+: 378.1368, found: 378.1365; purity >95%.

β-Carboline-N-oxide (2–1).

To a solution of harmine (500 mg, 2.35 mmol) in 8 mL of chloroform was added 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (1.22 g, 7.05 mmol) and refluxed for 24 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by flash chromatography using DCM/MeOH as eluent to give the desired product β-carboline-N-oxide 2–1 (255 mg, 47%) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.60 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 8.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.86 (d, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.85 (m, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.61 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ159.82, 143.39, 136.55, 132.79, 131.31, 122.35, 119.13, 115.62, 113.67, 109.57, 95.18, 55.78, 13.00; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C13H13N2O2+: 229.0972, found: 229.0962; purity >95%.

1-Hydroxymethyl-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (2–2).

Trifluoroacetic anhydride (2.20 mL, 15.87 mmol) was added to a stirred mixture of β-carboline-N-oxide (2–1) (724 mg, 3.17 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at 0 °C. After being stirred for 30 min, the mixture was refluxed 12 h. Upon completion of the reaction monitored by TLC, the mixture was concentrated and purified by flash column chromatography using DCM/MeOH as eluent to afford the 1-hydroxymethyl-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline 2–2 (358 mg, 49%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD): δ 8.39 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 8.27 (d, 1H, J = 6 Hz), 8.22 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.15 (s, 1H), 7.06 (m, 1H), 5.31 (s, 2H), 3.96 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ163.11, 145.98, 140.04, 133.09, 131.95, 129.49, 124.80, 115.17, 113.83, 112.77, 94.96, 58.27, 56.10; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C13H13N2O2+: 229.0972, found: 229.0967; purity >95%.

3-Bromo-2-hydroxyimino-propionic Acid Ethyl Ester (2–3).56

Hydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.81 g, 25.63 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of ethyl bromopyruvate (5.01 g, 25.63 mmol) in chloroform (50 mL) and methanol (70 mL) at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude was dissolved in dichloromethane (300 mL) and washed with 0.1 N of hydrochloric acid and brine. The organic layer was collected, dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to give 3-bromo-2-hydroxyimino-propionic acid ethyl ester 2–3 (4.36 g, 81%) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.08 (bs, 1H), 4.38 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.27 (s, 2H), 1.39 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); ESI: m/z [M + H]+ 209.97.

3-(6-Methoxy-1H-indol-3- yl)-propionic Acid Ethyl Ester (2–4).

A solution of 3-bromo-2-hydroxyimino-propionic acid ethyl ester 2–3 (1.75 g, 8.35 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was slowly added dropwise to a stirring mixture of 6-methoxyindole (1.23 g, 8.35 mmol) and Na2CO3 (4.86 g, 45.92 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 48 h, filtered through Celite, concentrated, and purified by flash column chromatography using ethyl acetate/hexanes as eluent to give 3-(6-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-propionic acid ethyl ester 2–4 (800 mg, 34%) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.91 (s, 1 H), 7.65 (d, 1 H, J = 12 Hz), 7.00 (s, 1 H), 6.81 (m, 1 H), 4.05 (s, 2 H), 4.26 (m, 2 H), 1.31 (t, 3 H, J = 6 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ164.20, 155.94, 150.66, 137.05, 122.75, 121.74, 119.65, 109.07, 94.78, 61.15, 55.53, 20.47, 14.36; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H17N2O4+: 227.1183, found: 227.1192; purity >95%.

2-Amino-3-(6-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-propionic Acid Ethyl Ester (2–5).

Zn dust (3.11 g, 47.62 mmol) was added portion wise to a stirred solution of 2–4 (1.64 g, 5.95 mmol) in acetic acid (20 mL) over 30 min. After addition, the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. After completion of the reaction monitored by LCMS, the mixture was filtered through Celite, washed with acetic acid (20 mL), and concentrated. The residue was neutralized with saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and extracted with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 3). Organic layers were collected, dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to get 2-amino-3-(6methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-propionic acid ethyl ester 2–5 (1.5 g, 96%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.64 (s, 1H), 7.35 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.82 (s, 1H), 6.63 (m, 1H), 3.99 (m, 2H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 3.56 (m, 1H), 2.86–2.97 (m, 2H), 1.90 (s, 1H), 1.10 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ155.85, 137.21, 122.60, 119.31, 110.32, 108.92, 94.81, 60.28, 55.60, 31.29, 14.42; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H19N2O3+: 263.1390, found: 263.1399; purity >95%.

Ethyl 1-methyl-7-methoxy-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole-3-carboxylate (2–7).

To the mixture of 2–5 (1 g, 3.81 mmol) and acetaldehyde (40% in water, 0.46 mL, 4.19 mmol) in 15 mL of dichloromethane, 0.4 mL of trifluoroacetic acid was added dropwise at 0 °C. Then, reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After completion of reaction as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was transferred to separatory funnel and washed with 50 mL of saturated sodium bicarbonate solution and brine. Organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under vacuum to get 2–6 as a white solid which was taken to next step without purification. A mixture of 2–6 (1.04 g, 3.81 mmol) and sulfur (248 mg, 7.63 mmol) in xylene (150 mL) was heated at reflux for 12 h. Then the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography using DCM/MeOH as eluent to afford ethyl 1-methyl-7-methoxy-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole-3-carboxylate 2–7 (755 mg, 75%) as brown solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.49 (s, 1 H), 9.10 (s, 1 H), 8.62 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.38 (m, 1 H), 4.84 (q, 2 H, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.33 (s, 3 H), 3.22 (s, 3 H), 1.82 (t, 1 H, J = 6.6 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, acetone-d6): δ166.31, 161.50, 143.09, 141.66, 137.98, 136.84, 128.25, 123.03, 116.01, 115.32, 110.61, 95.33, 60.72, 55.36, 19.94, 14.30; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C16H17N2O3+: 185.1234, found: 285.1237; purity >95%.

(1-Methyl-7-methoxy-9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-3-yl)methanol (2–8).

To a solution of ester 2–7 (160 mg, 0.56 mmol) in THF (15 mL) was added LiAlH4 (44 mg, 1.17 mmol) in portions at 0 °C, and then the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. Then the reaction was quenched by water and stirred at room temperature for 2 h, the slurry was filtered, the cake was washed with dichloromethane, the filtrate was concentrated to afford 2–8 (135 mg, 91%) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.31 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.83 (s, 1H), 6.98 (s, 1H), 6.82 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.25 (s, 1H), 4.64 (d, 2H, J = 5.4 Hz) 3.86 (s, 3 H), 2.68 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ160.43, 150.39, 142.71, 140.30, 133.87, 128.53, 122.95, 115.41, 109.31, 108.51, 94.99, 65.02, 55.71, 20.56; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H15N2O2+: 243.1128, found: 243.1131; purity >95%.

1,3-Dimethyl-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (2–9).58

To a solution of 2–8 (20 mg, 0.082 mmol) and PdCl2 (4 mg, 0.016 mmol) in EtOH (1 mL) was added Et3SiH (0.201 mL, 1.28 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 5 h. Upon completion of reaction monitored by TLC, catalyst was filtered over Celite and the filetrate was evaporated. The crude reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography using ethyl acetate as eluent to afford 2–9 (5 mg, 27%) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.01 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.66 (s, 1H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.81 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 3.86 (s, 3H), 2.68 (s, 3 H), 2.53 (s, 3 H); HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H15N2O+: 227.1179, found: 227.1169; purity >95%.

1-Acetyl-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (3–2).

To the mixture of 6-methoxytryptamine (300 mg, 1.57 mmol) and pyruvicaldehyde (45% in water, 0.34 mL, 1.89 mmol) in 6 mL of dichloromethane, 0.157 mL of trifluoroacetic acid was added drops wise at 0 °C. Then, reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After completion of reaction as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was transferred to separatory funnel and washed with 50 mL of saturated sodium bicarbonate solution and brine. Organic layer was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under vacuum to get 3–1 as yellow solid, which was taken to the next step without purification. A mixture of 3–1 (1.57 mmol) and KMnO4 (744 mg, 4.71 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Then the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by flash column chromatography using ethyl acetate as eluent to afford 1-acetyl-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline 3–2 (60 mg, 16%) as brown solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.75 (s, 1 H), 8.45 (d, 1 H, J = 5.4 Hz), 8.30 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.16 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.31 (m, 1 H), 6.92 (m, 1 H), 3.86 (s, 3 H), 2.77 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 201.88, 161.20, 144.06, 138.14, 135.78, 134.69, 131.58, 123.18, 118.88, 113.89, 110.24, 96.40, 55.76, 26.32; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H13N2O2+: 241.0972, found: 241.0966; purity > 95%.

1-(1-Hydroxyethyl)-7-methoxy-9H-β-carboline (3–3).

To a solution of 3–2 (12 mg, 0.05 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL) was added NaBH4 (4 mg, 0.1 mmol), and the mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. Then the reaction was quenched by water, transferred to separatory funnel, and extracted with ethyl acetate. Organic layer was collected, dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, and rotary evaporated to get the desired compound 3–3 (6 mg, 49%) as yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 11.09 (s, 1 H), 8.17 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.05 (d, 1 H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.86 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 7.17 (m, 1 H), 6.82 (m, 1 H), 5.67 (d, 1 H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.16 (m, 1 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 1.53 (d, 3 H, J = 6 Hz); 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 160.46, 148.37, 142.56, 137.25, 132.78, 128.93, 122.66, 114.66, 113.15, 109.32, 95.46, 69.59, 55.67, 23.36; HRMS (ESI): m/z [M + H]+ calcd for C14H15N2O2+: 243.1128, found: 243.1131; purity > 95%.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

DYRK1A Inhibition and β-Cell Proliferation of Harmine Analogues

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | % DYRK1A inhibition |

IC50 (nM)a | Compound | R | % DYRK1A inhibition |

IC50 (nM)a | ||

| 1000 nM | 300 nM | 1000 nM | 300 nM | ||||||

| Harmine | nd | nd | 28 | ||||||

| 1–6a |  |

89 | 72 | 159 | 1–6i |  |

22 | 1 | nd |

| 1–6b |  |

97 | 90 | 264 | 1–6j |  |

60 | 27 | nd |

| 1–6c |  |

81 | 57 | 1500 | |||||

| 1–6d |  |

91 | 71 | 123 | |||||

| 1–6e |  |

61 | 34 | nd | 1–5 | 100 | 98 | 8.8 | |

| 1–4 | 38 | 17 | nd | ||||||

| 2–2 |  |

75 | 49 | 54.8 | |||||

| 1–6f |  |

84 | 57 | 221 | 2–8 | 98 | 90 | 49.5 | |

| 1–6g |  |

38 | 15 | nd | |||||

| 1–6h |  |

49 | 12 | nd | 2–9 | - | - | 971 | |

| 3–2 |  |

92 | 85 | 66.7 | |||||

| 3–3 |  |

67 | 38 | 858 | |||||

IC50 values are determined using ten serial 3-fold dilutions (in duplicate). nd = not determined.

Acknowledgments

Funding

K.K., P.W., R.J.D. and A.F.S. were supported in part by NIH Grant NIDDK R01DK DK105015–01-A1, UC4 DK104211, P-30 DK 020541, JDRF 2-SRA-2017 514–S-B. K.K. and R.J.D. were supported in part by Icahn School of Medicine Seed Fund 0285–3980. This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the NIDDK-supported Einstein-Sinai Diabetes Research Center (E-S DRC) and the NIDDK Human Ilseet Research Network.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DYRK1A

the dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A

- DS

Down syndrome

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- EGCg

epigallocatechin gallate

- INDY

inhibitor of DYRK1A

- FINDY

folding intermediate inhibitor of DYRK1A

- DANDY

diaryl azaindole inhibitor of DYRK1A

- CNS

central nervous system

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- SAR

structure activity relationship

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00658.

DYRK1A binding curves, spectral data (PDF)

Full kinome scans of harmine, compounds 2–2 and 2–8 (PDB1 and PDB)

Molecular formula strings (CSV)

REFERENCES

- (1).Becker W; Soppa U; Tejedor FJ DYRK1A: A potential drug target for multiple down syndrome neuropathologies. CNS Neurol. Disord.: Drug Targets 2014, 13 (1), 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wegiel J; Gong C-X; Hwang Y-W The role of DYRK1A in neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS J. 2011, 278 (2), 236–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Smith B; Medda F; Gokhale V; Dunckley T; Hulme C Recent advances in the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of selective DYRK1A inhibitors: A new avenue for a disease modifying treatment of alzheimer’s? ACS Chem. Neurosci 2012, 3 (11), 857–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ionescu A; Dufrasne F; Gelbcke M; Jabin I; Kiss R; Lamoral-Theys D DYRK1A kinase inhibitors with emphasis on cancer. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem 2012, 12 (13), 1315–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fernandez-Martinez P; Zahonero C; Sanchez-Gomez P DYRK1A: the double-edged kinase as a protagonist in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Oncol 2015, 2, e970048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wang P; Alvarez-Perez J-C; Felsenfeld DP; Liu H; Sivendran S; Bender A; Kumar A; Sanchez R; Scott DK; Garcia-Ocana A; Stewart AF A high-throughput chemical screen reveals that harmine-mediated inhibition of DYRK1A increases human pancreatic beta cell replication. Nat. Med 2015, 21 (4), 383–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shen W; Taylor B; Jin Q; Nguyen-Tran V; Meeusen S; Zhang Y-Q; Kamireddy A; Swafford A; Powers AF; Walker J; Lamb J; Bursalaya B; DiDonato M; Harb G; Qiu M; Filippi CM; Deaton L; Turk CN; Suarez-Pinzon WL; Liu Y; Hao X; Mo T; Yan S; Li J; Herman AE; Hering BJ; Wu T; Seidel HM; McNamara P; Glynne R; Laffitte B Inhibition of DYRK1A and GSK3B induces human β-cell proliferation. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8372–8382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rachdi L; Kariyawasam D; Aiello V; Herault Y; Janel N; Delabar J-M; Polak M; Scharfmann R Dyrk1A induces pancreatic β cell mass expansion and improves glucose tolerance. Cell Cycle 2014, 13 (14), 2221–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dirice E; Walpita D; Vetere A; Meier BC; Kahraman S; Hu J; Dancik V; Burns SM; Gilbert TJ; Olson DE; Clemons PA; Kulkarni RN; Wagner BK Inhibition of DYRK1A stimulates human beta-cell proliferation. Diabetes 2016, 65 (6), 1660–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Becker W; Sippl W Activation, regulation, and inhibition of DYRK1A. FEBS J. 2011, 278 (2), 246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Guedj F; Sebrie C; Rivals I; Ledru A; Paly E; Bizot JC; Smith D; Rubin E; Gillet B; Arbones M; Delabar JM Green tea polyphenols rescue of brain defects induced by overexpression of DYRK1A. PLoS One 2009, 4 (2), e4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).McLauchlan H; Elliott M; Cohen P The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem. J 2003, 371 (1), 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tahtouh T; Elkins JM; Filippakopoulos P; Soundararajan M; Burgy G; Durieu E; Cochet C; Schmid RS; Lo DC; Delhommel F; Oberholzer AE; Pearl LH; Carreaux F; Bazureau J-P; Knapp S; Meijer L Selectivity, cocrystal structures, and neuroprotective properties of leucettines, a family of protein kinase inhibitors derived from the marine sponge alkaloid leucettamine B. J. Med. Chem 2012, 55 (21), 9312–9330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Naert G; Ferre V; Meunier J; Keller E; Malmstrom S; Givalois L; Carreaux F; Bazureau J-P; Maurice T Leucettine L41, a DYRK1A-preferential DYRKs/CLKs inhibitor, prevents memory impairments and neurotoxicity induced by oligomeric Aβ25–35 peptide administration in mice. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 2015, 25 (11), 2170–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Cozza G; Mazzorana M; Papinutto E; Bain J; Elliott M; di Maira G; Gianoncelli A; Pagano MA; Sarno S; Ruzzene M; Battistutta R; Meggio F; Moro S; Zagotto G; Pinna LA Quinalizarin as a potent, selective and cell-permeable inhibitor of protein kinase CK2. Biochem. J 2009, 421 (3), 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ahmadu A; Abdulkarim A; Grougnet R; Myrianthopoulos V; Tillequin F; Magiatis P; Skaltsounis A-L Two new peltogynoids from Acacia nilotica Delile with kinase inhibitory activity. Planta Med. 2010, 76 (5), 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sarno S; Mazzorana M; Traynor R; Ruzzene M; Cozza G; Pagano MA; Meggio F; Zagotto G; Battistutta R; Pinna LA Structural features underlying the selectivity of the kinase inhibitors NBC and dNBC: role of a nitro group that discriminates between CK2 and DYRK1A. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2012, 69 (3), 449–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sanchez C; Salas AP; Brana AF; Palomino M; Pineda-Lucena A; Carbajo RJ; Mendez C; Moris F; Salas JA Generation of potent and selective kinase inhibitors by combinatorial biosynthesis of glycosylated indolocarbazoles. Chem. Commun 2009, No. 27, 4118–4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ogawa Y; Nonaka Y; Goto T; Ohnishi E; Hiramatsu T; Kii I; Yoshida M; Ikura T; Onogi H; Shibuya H; Hosoya T; Ito N; Hagiwara M, Development of a novel selective inhibitor of the Down syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A. Nat. Commun 2010, 1, Oga1/1-Oga1/9,SOga1/1-SOga1/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gourdain S; Dairou J; Denhez C; Bui LC; Rodrigues-Lima F; Janel N; Delabar JM; Cariou K; Dodd RH Development of DANDYs, new 3,5-Diaryl-7-azaindoles demonstrating potent DYRK1A kinase inhibitory activity. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56 (23), 9569–9585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kii I; Sumida Y; Goto T; Sonamoto R; Okuno Y; Yoshida S; Kato-Sumida T; Koike Y; Abe M; Nonaka Y; Ikura T; Ito N; Shibuya H; Hosoya T; Hagiwara M Selective inhibition of the kinase DYRK1A by targeting its folding process. Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 11391–11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Koo KA; Kim ND; Chon YS; Jung M-S; Lee B-J; Kim JH; Song W-J QSAR analysis of pyrazolidine-3,5-diones derivatives as Dyrk1A inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2009, 19 (8), 2324–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kim ND; Yoon J; Kim JH; Lee JT; Chon YS; Hwang M-K; Ha I; Song W-J Putative therapeutic agents for the learning and memory deficits of people with Down syndrome. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2006, 16 (14), 3772–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rosenthal AS; Tanega C; Shen M; Mott BT; Bougie JM; Nguyen D-T; Misteli T; Auld DS; Maloney DJ; Thomas CJ Potent and selective small molecule inhibitors of specific isoforms of Cdc2-like kinases (Clk) and dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinases (Dyrk). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 21 (10), 3152–3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Giraud F; Alves G; Debiton E; Nauton L; Thery V; Durieu E; Ferandin Y; Lozach O; Meijer L; Anizon F; Pereira E; Moreau P Synthesis, protein kinase inhibitory potencies, and in vitro antiproliferative activities of meridianin derivatives. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (13), 4474–4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Echalier A; Bettayeb K; Ferandin Y; Lozach O; Clement M; Valette A; Liger F; Marquet B; Morris JC; Endicott JA; Joseph B; Meijer L Meriolins (3-(Pyrimidin-4-yl)-7-azaindoles): Synthesis, kinase inhibitory activity, cellular effects, and structure of a CDK2/Cyclin A/Meriolin complex. J. Med. Chem 2008, 51 (4), 737–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Akue-Gedu R; Debiton E; Ferandin Y; Meijer L; Prudhomme M; Anizon F; Moreau P Synthesis and biological activities of aminopyrimidyl-indoles structurally related to meridianins. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2009, 17 (13), 4420–4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kassis P; Brzeszcz J; Beneteau V; Lozach O; Meijer L; Le Guevel R; Guillouzo C; Lewinski K; Bourg S; Colliandre L; Routier S; Merour J-Y Synthesis and biological evaluation of new 3-(6-hydroxyindol-2-yl)-5-(Phenyl) pyridine or pyrazine V-Shaped molecules as kinase inhibitors and cytotoxic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2011, 46 (11), 5416–5434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Neagoie C; Vedrenne E; Buron F; Merour J-Y; Rosca S; Bourg S; Lozach O; Meijer L; Baldeyrou B; Lansiaux A; Routier S Synthesis of chromeno[3,4-b]indoles as Lamellarin D analogues: A novel DYRK1A inhibitor class. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2012, 49, 379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Falke H; Chaikuad A; Becker A; Loaec N; Lozach O; Abu Jhaisha S; Becker W; Jones PG; Preu L; Baumann K; Knapp S; Meijer L; Kunick C 10-Iodo-11H-indolo[3,2-c]quinoline-6-carboxylic acids are selective inhibitors of DYRK1A. J. Med. Chem 2015, 58 (7), 3131–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Foucourt A; Hedou D; Dubouilh-Benard C; Desire L; Casagrande A-S; Leblond B; Loaec N; Meijer L; Besson T Design and synthesis of thiazolo[5,4-f]quinazolines as DYRK1A inhibitors, part I. Molecules 2014, 19 (10), 15546–15571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Coutadeur S; Benyamine H; Delalonde L; de Oliveira C; Leblond B; Foucourt A; Besson T; Casagrande A-S; Taverne T; Girard A; Pando MP; Desire L A novel DYRK1A (Dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A) inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: effect on Tau and amyloid pathologies in vitro. J. Neurochem 2015, 133 (3), 440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Abdolazimi Y; Lee S; Xu H; Allegretti P; Horton TM; Yeh B; Moeller HP; McCutcheon D; Armstrong NA; Annes JP; Allegretti P; Horton TM; McCutcheon D; Smith M; Annes JP; Horton TM; Nichols RJ; Shalizi A; Smith M, CC-401 promotes β-Cell replication via pleiotropic consequences of DYRK1A/B inhibition. Endocrinology 2018, DOI: 10.1210/en.201800083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Annes JP; Ryu JH; Lam K; Carolan PJ; Utz K; Hollister-Lock J; Arvanites AC; Rubin LL; Weir G; Melton DA Adenosine kinase inhibition selectively promotes rodent and porcine islet β-cell replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109 (10), 3915–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Brierley DI; Davidson C Developments in harmine pharmacology - Implications for ayahuasca use and drug-dependence treatment. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 39 (2), 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Airaksinen MM; Lecklin A; Saano V; Tuomisto L; Gynther J Tremorigenic effect and inhibition of tryptamine and serotonin receptor binding by β-carbolines. Pharmacol. Toxicol 1987, 60 (1), 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fuentes JA; Longo VG Central effects of harmine, harmaline, and related β-carbolines. Neuropharmacology 1971, 10 (1), 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Frost D; Meechoovet B; Wang T; Gately S; Giorgetti M; Shcherbakova I; Dunckley T β-carboline compounds, including harmine, inhibit DYRK1A and tau phosphorylation at multiple Alzheimer’s disease-related sites. PLoS One 2011, 6 (5), e19264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chen Q; Chao R; Chen H; Hou X; Yan H; Zhou S; Peng W; Xu A Antitumor and neurotoxic effects of novel harmine derivatives and structure-activity relationship analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114 (5), 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ishida J; Wang H-K; Bastow KF; Hu C-Q; Lee K-H Antitumor agents 201.1 Cytotoxicity of harmine and β-carboline analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 1999, 9 (23), 3319–3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Cao R; Chen Q; Hou X; Chen H; Guan H; Ma Y; Peng W; Xu A Synthesis, acute toxicities, and antitumor effects of novel 9-substituted β-carboline derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2004, 12 (17), 4613–4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Cao R; Fan W; Guo L; Ma Q; Zhang G; Li J; Chen X; Ren Z; Qiu L Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of harmine derivatives as potential antitumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2013, 60, 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Zhang X-F; Sun R.-q.; Jia Y.-f.; Chen Q; Tu R-F; Li K.-k.; Zhang X-D; Du R-L; Cao R.-h. Synthesis and mechanisms of action of novel harmine derivatives as potential antitumor agents. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 33204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Cao R; Peng W; Chen H; Ma Y; Liu X; Hou X; Guan H; Xu A DNA binding properties of 9-substituted harmine derivatives. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2005, 338 (3), 1557–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Sobhani AM; Ebrahimi S-A; Mahmoudian M An in vitro evaluation of human DNA topoisomerase I inhibition by Peganum harmala L. seeds extract and its β-carboline alkaloids. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 2002, 5 (1), 18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Song Y; Kesuma D; Wang J; Deng Y; Duan J; Wang JH; Qi RZ Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases and cell proliferation by harmine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2004, 317 (1), 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Cao M-R; Li Q; Liu Z-L; Liu H-H; Wang W; Liao X-L; Pan Y-L; Jiang J-W Harmine induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells via mitochondrial signaling pathway. Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Dis. Int 2011, 10 (6), 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Taira Z; Kanzawa S; Dohara C; Ishida S; Matsumoto M; Sakiya Y Intercalation of six β-carboline derivatives into DNA. Jpn. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1997, 43 (2), 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Finan B; Yang B; Ottaway N; Stemmer K; Mueller TD; Yi C-X; Habegger K; Schriever SC; Garcia-Caceres C; Kabra DG; Hembree J; Holland J; Raver C; Seeley RJ; Hans W; Irmler M; Beckers J; de Angelis MH; Tiano JP; Mauvais-Jarvis F; Perez-Tilve D; Pfluger P; Zhang L; Gelfanov V; DiMarchi RD; Tschoep MH Targeted estrogen delivery reverses the metabolic syndrome. Nat. Med 2012, 18 (12), 1847–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Luis SV; Burguete MI The Fischer indole synthesis of 8-methyl-5-substituted-1-oxo-β-carbolines: a remarkable high yield of a [1,2]-methyl migration. Tetrahedron 1991, 47 (9), 1737–1744. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Roggero CM; Giulietti JM; Mulcahy SP Efficient synthesis of eudistomin U and evaluation of its cytotoxicity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2014, 24 (15), 3549–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Thompson MJ; Louth JC; Little SM; Jackson MP; Boursereau Y; Chen B; Coldham I Synthesis and evaluation of 1-amino-6-halo-β-carbolines as antimalarial and antiprion agents. ChemMedChem 2012, 7 (4), 578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Henderson JL; McDermott SM; Buchwald SL Palladium-catalyzed amination of unprotected halo-7-azaindoles. Org. Lett 2010, 12 (20), 4438–4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Lin G; Wang Y; Zhou Q; Tang W; Wang J; Lu T A facile synthesis of 3-substituted 9H-pyrido[3,4-b]indol-1(2H)-one derivatives from 3-substituted β-carbolines. Molecules 2010, 15, 5680–5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fontenas C; Bejan E; Haddou HA; Balavoine GGA The Boekelheide Reaction: trifluoroacetic anhydride as a convenient acylating agent. Synth. Commun 1995, 25 (5), 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Park K; Gopalsamy A; Aplasca A; Ellingboe JW; Xu W; Zhang Y; Levin JI Synthesis and activity of tryptophan sulfonamide derivatives as novel non-hydroxamate TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2009, 17 (11), 3857–3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Song H; Liu Y; Liu Y; Wang L; Wang Q Synthesis and antiviral and fungicidal activity evaluation of β-carboline, dihydro-β-carboline, tetrahydro-β-carboline alkaloids, and their derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem 2014, 62 (5), 1010–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Mirza-Aghayan M; Boukherroub R; Rahimifard M A simple and efficient hydrogenation of benzyl alcohols to methylene compounds using triethylsilane and a palladium catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50 (43), 5930–5932. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Soundararajan M; Roos AK; Savitsky P; Filippakopoulos P; Kettenbach AN; Olsen JV; Gerber SA; Eswaran J; Knapp S; Elkins JM Structures of down syndrome kinases, DYRKs, reveal mechanisms of kinase activation and substrate recognition. Structure 2013, 21 (6), 986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Balint B; Weber C; Cruzalegui F; Burbridge M; Kotschy A Structure-based design and synthesis of harmine derivatives with different selectivity profiles in kinase versus monoamine oxidase Inhibition. ChemMedChem 2017, 12 (12), 932–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Boursereau Y; Coldham I Synthesis and biological studies of 1-amino β-carbolines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2004, 14 (23), 5841–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sherman W; Day T; Jacobson MP; Friesner RA; Farid R Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J. Med. Chem 2006, 49 (2), 534–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Friesner RA; Banks JL; Murphy RB; Halgren TA; Klicic JJ; Mainz DT; Repasky MP; Knoll EH; Shelley M; Perry JK; Shaw DE; Francis P; Shenkin PS Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47 (7), 1739–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Madhavi Sastry G; Adzhigirey M; Day T; Annabhimoju R; Sherman W Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des 2013, 27 (3), 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Li J; Abel R; Zhu K; Cao Y; Zhao S; Friesner RA The VSGB 2.0 model: A next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 2011, 79 (10), 2794–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).LanthaScreen Eu Kinase Binding Assay - Customer Protocol and Assay Conditions documents located at. https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/industrial/pharma-biopharma/drug-discovery-development/target-and-lead-identification-and-validation/kinasebiology/kinase-activity-assays/lanthascreentm-eu-kinase-binding-assay.html. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- (67).Fabian MA; Biggs WH; Treiber DK; Atteridge CE; Azimioara MD; Benedetti MG; Carter TA; Ciceri P; Edeen PT; Floyd M; Ford JM; Galvin M; Gerlach JL; Grotzfeld RM; Herrgard S; Insko DE; Insko MA; Lai AG; Lelias J-M; Mehta SA; Milanov ZV; Velasco AM; Wodicka LM; Patel HK; Zarrinkar PP; Lockhart DJ A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23 (3), 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.