Abstract

N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis, the only two human pathogens of Neisseria, are closely related species. But the niches they survived in and their pathogenic characteristics are distinctly different. However, the genetic basis of these differences has not yet been fully elucidated. In this study, comparative genomics analysis was performed based on 15 N. gonorrhoeae, 75 N. meningitidis, and 7 nonpathogenic Neisseria genomes. Core-pangenome analysis found 1111 conserved gene families among them, and each of these species groups had opening pangenome. We found that 452, 78, and 319 gene families were unique in N. gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis, and both of them, respectively. Those unique gene families were regarded as candidates that related to their pathogenicity and niche adaptation. The relationships among them have been partly verified by functional annotation analysis. But at least one-third genes for each gene set have not found the certain functional information. Simple sequence repeat (SSR), the basis of gene phase variation, was found abundant in the membrane or related genes of each unique gene set, which may facilitate their adaptation to variable host environments. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis found at least five distinct PPI clusters in N. gonorrhoeae and four in N. meningitides, and 167 and 52 proteins with unknown function were contained within them, respectively.

1. Introduction

The Neisseria species are a group of Gram-negative, oxidase-positive, β-proteobacteria organisms within the family Neisseriaceae. They typically appear in pairs with the adjacent sides flattened and occasionally monococcus or tetrads and grow best at 37°C in the animal body or media [1, 2]. Up to now, at least 30 species of Neisseria have been identified (http://www.bacterio.net/neisseria.html). The majority of Neisseria species were found primarily on mucosal and dental surfaces in warm-blooded animals as harmless commensals, including N. lactamica, N. elongata, and N. mucosa [2–4]. However, two of them are globally significant pathogens: N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae.

The N. meningitides, a causative agent of meningitis, normally colonize in the upper respiratory tract. It is carried by more than 10% young adults without causing diseases [5]. However, for children under the age of 5 years or adults older than 65 years, it can cause meningococcal disease, which is a life-threatening illness and leads to about 10% case fatality [5, 6] and devastating sequelae, such as deafness and loss of limbs, among survivors. Its serotype distribution varies pronouncedly throughout the world. Six out of thirteen identified capsular types of N. meningitidis, including A, B, C, W, X, and Y, account for most disease cases worldwide [7]. The multiple subtypes have hindered the development of vaccines to provide broad-spectrum protection from meningococcal disease [8]. N. gonorrhoeae is an obligate human pathogen. It typically causes mucosal infection of the urogenital tract, rectum, pharynx, or eye, even disseminated infections [9, 10]. Untreated N. gonorrhoeae infections can cause serious sequelae, such as infertility, urogenital tract abscesses, and adverse pregnancy outcomes, which significantly degrade the quality of life [10]. There are 106.1 million cases of N. gonorrhoeae per year in the world [11]. In recent years, the number of cases of gonorrhea has risen significantly. But there is still no effective vaccine to prevent gonorrhea until now [12]. And worse yet, the multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains have been found widespread emergence [12]. Thus, it is significant to thoroughly understand the adaptive and pathogenic mechanism of Neisseria pathogens.

Previous studies found that these two Neisseria pathogens shared plenty of virulence genes [13]. In recent years, much work has been done to explore their key factors of virulence, interaction with host cells, mechanism of immune escape, and so forth. For example, type IV pili, encoded by genes pilC, pilD, pilE, pilS, etc., is required for initial attachment, twitching motility and competence for natural transformation and autoagglutination [14, 15]. fHbp and nspA, two immune modulators, can bind to complement factor H to inhibit host immune defenses [16, 17]. With the development of new sequence technologies, enormous genomes of Neisseria strains have been sequenced, which makes our understanding of genetic basis of biological characters and biochemical mechanisms more systemic and all-round. Based on comparative genomics of 17 Neisseria strains, Marri et al. found that widespread virulence genes exchanged among them and commensal Neisseria served as reservoirs of virulence genes [18]. Phase variation was found very prevalent in Neisseria pathogens and plays an important role in their niche adaptation and virulence [19, 20].

Although Neisseria meningitides and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are closely related, the niches they survived in and pathogenic characteristics are distinctly different. The genetic background of these differences has not yet been fully defined. In addition, previous studies focus on a limited number of genes or genomes. There remains a need for a comprehensive picture of similarities and differences of their genome composition to have a better understanding of the genetic basis of their phenotypic features.

In this study, we performed Neisseria genus-wide comparative genomics analysis based on all the Neisseria complete genomes that are available on public databases. We intended to identify genes that could underlie the apparent differences of specialized niche and pathogenic characteristics of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae. Moreover, the genus-wide comparative genomics can give us an overall and profound understanding of genome structure and the evolutional relationships of all the sequenced Neisseria species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Retrieval and Genome Management

In this study, the GenBank (.gbk) files of Neisseria species with complete genome were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome), including 15 N. gonorrhoeae strains and 85 N. meningitidis strains. Because of few genomes sequenced for nonpathogenic Neisseria strains (NPNS), 7 genomes which have at most 10 scaffolds were retrieved. In order to keep the consistence of raw data, the sequences of chromosome, plasmids, and scaffolds for each strain were pasted together into a pseudochromosome by sequence “NNNNNCATTCCATTCATTAATTAATTAATGAATGAATGNNNNN,” which does not affect the genome structure annotation results [21].

To avoid the contradiction that comes from using different annotation pipelines in different research projects, uniform reannotation pipeline was utilized to each genome. In particular, Glimmer v3.02 [22] was used to predict open reading frames (ORFs). The program RNAmmer v1.2 [23] and tRNAscan-SE v1.4 [24] were used to predict ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, respectively.

SSRs of each genome were identified by tandem repeats finder v4.09 [25]. In order to adapt the criteria as the previous study [20, 26], parameters were set as follows: match weight = 4, mismatch penalty = 20, indel penalty = 20, match probability = 80, indel probability = 10, min score to report = 24, and max period size to report = 10. The high penalty values ensured that there were without any mismatches within the repeats and, at the same time, the repeats in which a unit length is greater than 10 bases were discarded.

The candidate contingency loci were identified according to the following criteria. The repeats must be located within the region of an ORF or at most 100 bp upstream of the ORF. Single-base homopolymers must have a length of greater than 6 bp, and dinucleotide repeats must consist of at least 3 repeats. The other repeats with a maximum unit of 10 bases must consist of at least 2 repeats.

2.2. Protein Cluster Analysis and Gene Families

All the predicted genes for each Neisseria strain were translated into proteomes. Homologous proteins were searched by all-against-all BLASTP comparisons, which means all the proteins existing in one genome against themselves or all the proteins in other genomes [27]. Those pairwise proteins which meet the threshold (identity > 50%, query coverage > 50%, and e-value ≤ 1e − 05) were used for further analysis. Then, the Markov clustering algorithm (MCL) [28, 29] was implemented to cluster these blast results. The percentage of homologous proteome for any two genomes was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where P s is the percentage of shared proteome, N s is the number of shared proteins, N a is the number of one strain protein, and N b is the number of another strain protein.

The comparison results were displayed in a heat map, which showed the percentage of shared proteome between or within the strain by using the gradation of color.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

To investigate the phylogenetic relationship of the 107 Neisseria strains, 16s rRNA was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus dysgalactiae were used as outgroups. The multiple sequence alignment was performed by MAFFT v7.123b [30]. Then, the evolutionary history was inferred by the neighbour joining (NJ) [31] method, and the analysis was conducted in MEGA v7 [32] with 1000 bootstrap replications.

To assess the reliability and consistency of the 16s rRNA tree, a genome-scale approach was used to construct the phylogenetic tree [33]. All the single-copy genes were extracted and aligned using MAFFT v7.123b. Then, the results were concatenated for each strain with uniform order. Gblocks v0.91b [34] was used to eliminate poorly aligned positions and divergent regions. Maximum likelihood (ML) and 100 times bootstrap resampling approach were used to compute the phylogenetic tree using RAxML version 8.2.8 [35]. The final tree was visualized by MEGA.

2.4. Estimation of Core and Pangenome Size

As follows, two mathematic models [21, 36] were employed to simulate relations between core/pangenome size and genome number, respectively.

Fitting for the pangenome profile model is as follows:

| (2) |

where y is the pangenome size, x is the genome number, and A 1, B 1, and C 1 are the fitting parameters.

Fitting for the core genome profile model is as follows:

| (3) |

where y is the core genome size, x is the genome number, and A 2, B 2, and C 2 are the fitting parameters.

Four genome groups, including all of the tested 107 Neisseria strains (ATNS), 85 N. meningitidis strains (NMS), 15 N. gonorrhoeae (NGS), and 7 nonpathogenic Neisseria strains (NPNS), were analyzed and visualized by R-3.2.5 (https://www.r-project.org/), respectively. Specifically, for each group, 100 random permutation lists of all the genomes were generated. Subsequently, we calculated the changes of core/pangenome size at each time a new genome added for each list. Finally, the median values of all counts were used to curve fitting.

2.5. Functional Categorization of the Core and Dispensable Genomes

As described in Section 2.4, the dataset was combined into four groups. For core and dispensable genomes of each group, functional annotation and classification were performed using the BLASTP program against Clusters of Orthologous Group (COG, 2014 update, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/) database [37], respectively. The function classification results were shown in a bar chart.

2.6. Unique Gene Analyses of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae

The unique genes for each genome group were identified, based on the protein cluster analysis. The gene families shared by NGS, NMS, and NPNS groups and their combinations were detected by a python script. Then, the statistic results were plotted with a Venn diagram using VennDiagram v1.6.0 [38] in R. The operon predictions of N. meningitidis MC58 and N. gonorrhoeae 32867 were performed using database for prokaryotic operons (DOOR) v2.0 [39]. Then, function annotations of these genes were performed based on consecutive comparisons against public protein databases as follows: UniProt/Siwss-Prot [40], virulence factor database (VFDB) [41], InterProScan v7 [42], and NCBI nonredundant (NR) protein database [43]. Furthermore, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs, 2014 update) [44] and evolutionary genealogy of genes: nonsupervised orthologous groups (eggNOG) v4.5.1 [45] were used to classify orthologous groups. Finally, all the results above were manually integrated into consolidated results.

2.7. SSR Locus Analysis of the Unique Genes for Neisseria Pathogens

The distribution of functional category and SSR loci of unique genes for Neisseria pathogens were analyzed to assess whether phase-variable genes that code for certain functions were more frequent than expected by chance. The statistic of SSR for each gene set was based on all the corresponding genome sets, and the results were presented as the mean ± standard error.

2.8. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis of Unique Protein Sets

To better understand the role of unique protein sets of Neisseria pathogens in their niche adaptability and pathogenicity, PPI network analysis was performed using Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING v10.5, https://string-db.org/). Then, the PPI results were visualized by Cytoscape 3.6.1 [46].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genome Statistics and General Features

There are 820 N. meningitidis and 434 N. gonorrhoeae genome records in NCBI genome database. Additionally, some nonpathogenic Neisseria species, such as N. lactamica, N. elongata, N. mucosa, N. weaveri, and N. zoodegmatis, were sequenced [47–49]. In this study, total of 107 genomes of Neisseria strain were used, including 85 N. meningitidis, 15 N. gonorrhoeae complete genomes, and 7 NPNS, of which six have complete genomes and N. mucosa C102 has seven scaffolds (Table 1). Only three N. gonorrhoeae strains have plasmid. The average genome size of 107 strains is 2,201,350 bp, ranging from 2,139,957 (N. meningitidis LNP21362) to 2,552,522 (N. zoodegmatis NCTC12230). The average GC content of all the genomes is 51.76% (N. gonorrhoeae: 52.43%, N. meningitidis: 51.68%, and NPNS: 51.49%), ranging from 49% (N. weaveri NCTC13585) to 54.26% (N. elongata ATCC 29315). The average number of open reading frame (ORF) is 2396, ranging from 2132 (N. mucosa C102) to 2668 (N. zoodegmatis NCTC12230).

Table 1.

Genomic details of Neisseria species used in the present study.

| Organism | Accession number | Genome size (bp) | GC content (%) | # of scaffolds | # of plasmids | # of ORFs | rRNA | tRNA | Morphology | Natural host | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Diplococcus | Human | |||||||||

| 32867 | CP016015 | 2,218,818 | 52.41 | 1 | 0 | 2545 | 12 | 55 | |||

| 34530 | CP016016 | 2,228,373 | 52.35 | 1 | 0 | 2557 | 12 | 55 | |||

| 34769 | CP016017 | 2,220,340 | 52.43 | 1 | 0 | 2541 | 12 | 55 | |||

| 35_02 | CP012028 | 2,173,235 | 52.6 | 1 | 0 | 2468 | 12 | 55 | [57] | ||

| FA_1090 | AE004969 | 2,153,922 | 52.69 | 1 | 0 | 2448 | 12 | 55 | |||

| FA19 | CP012026 | 2,232,367 | 52.38 | 1 | 0 | 2573 | 12 | 55 | [57] | ||

| FA6140 | CP012027 | 2,168,698 | 52.59 | 1 | 0 | 2485 | 12 | 55 | [57] | ||

| FDAARGOS_204 | CP020415 | 2,212,422 | 52.45 | 1 | 0 | 2541 | 12 | 55 | |||

| FDAARGOS_205 | CP020417 | 2,278,895 | 52.26 | 1 | 2 | 2665 | 12 | 54 | |||

| FDAARGOS_207 | CP020419 | 2,189,343 | 52.36 | 1 | 0 | 2497 | 12 | 55 | |||

| MS11 | CP003909 | 2,237,793 | 52.36 | 1 | 1 | 2591 | 12 | 55 | |||

| NCCP11945 | CP001051 | 2,236,178 | 52.36 | 1 | 1 | 2574 | 12 | 55 | [58] | ||

| NCTC13798 | NZ_LT906440 | 2,230,241 | 52.35 | 1 | 0 | 2551 | 12 | 55 | |||

| NCTC13799 | NZ_LT906437 | 2,172,222 | 52.56 | 1 | 0 | 2469 | 12 | 55 | |||

| NCTC13800 | NZ_LT906472 | 2,226,638 | 52.36 | 1 | 0 | 2549 | 12 | 55 | |||

| Neisseria meningitidis | Diplococcus | Human, chimpanzee | |||||||||

| 53442 | CP000381 | 2,153,416 | 51.7 | 1 | 0 | 2298 | 12 | 59 | [59] | ||

| 331401 | CP012694 | 2,191,116 | 51.86 | 1 | 0 | 2361 | 12 | 59 | |||

| 38277 | CP015886 | 2,264,278 | 51.4 | 1 | 0 | 2458 | 12 | 60 | |||

| 510612 | CP007524 | 2,188,020 | 51.83 | 1 | 0 | 2368 | 12 | 59 | [60] | ||

| 8013 | FM999788 | 2,277,550 | 51.43 | 1 | 0 | 2415 | 12 | 59 | [61] | ||

| alpha14 | AM889136 | 2,145,295 | 51.95 | 1 | 0 | 2279 | 12 | 58 | [62] | ||

| alpha710 | CP001561 | 2,242,947 | 51.69 | 1 | 0 | 2406 | 12 | 57 | [63] | ||

| B6116_77 | CP007667 | 2,187,672 | 51.66 | 1 | 0 | 2386 | 12 | 59 | [64] | ||

| COL-201504-11 | CP017257 | 2195,573 | 51.65 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 12 | 59 | |||

| DE10444 | CP012392 | 2,170,619 | 51.63 | 1 | 0 | 2279 | 12 | 59 | |||

| DE8555 | CP012393 | 2,207,932 | 51.81 | 1 | 0 | 2394 | 12 | 59 | |||

| DE8669 | CP012391 | 2,230,103 | 51.42 | 1 | 0 | 2362 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FAM18 | AM421808 | 2,194,961 | 51.62 | 1 | 0 | 2324 | 12 | 59 | [65] | ||

| FDAARGOS_209 | CP020420 | 2,181,227 | 51.89 | 1 | 0 | 2364 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FDAARGOS_210 | CP020421 | 2,273,677 | 51.52 | 1 | 0 | 2414 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FDAARGOS_211 | CP020422 | 2,305,790 | 51.43 | 1 | 0 | 2469 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FDAARGOS_212 | CP020423 | 2,244,857 | 51.5 | 1 | 0 | 2426 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FDAARGOS_214 | CP020401 | 2,397,439 | 51.05 | 1 | 0 | 2621 | 12 | 59 | |||

| FDAARGOS_215 | CP020402 | 2,305,808 | 51.43 | 1 | 0 | 2473 | 12 | 59 | |||

| G2136 | CP002419 | 2,184,862 | 51.68 | 1 | 0 | 2352 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| H44_76 | CP002420 | 2,240,883 | 51.45 | 1 | 0 | 2379 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| L91543 | CP016684 | 2,173,191 | 51.72 | 1 | 0 | 2357 | 12 | 59 | |||

| LNP21362 | CP006869 | 2,139,957 | 51.82 | 1 | 0 | 2297 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M01-240149 | CP002421 | 2,223,518 | 51.44 | 1 | 0 | 2360 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| M01-240355 | CP002422 | 2,287,777 | 51.5 | 1 | 0 | 2413 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| M04-240196 | CP002423 | 2,250,449 | 51.4 | 1 | 0 | 2383 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| M0579 | CP007668 | 2324,822 | 51.37 | 1 | 0 | 2456 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M07149 | CP016650 | 2,173,513 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2377 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M07161 | CP016675 | 2,169,790 | 51.75 | 1 | 0 | 2385 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M07162 | CP016644 | 2,193,742 | 51.67 | 1 | 0 | 2413 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M07165 | CP016880 | 2,207,174 | 51.58 | 1 | 0 | 2442 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M07999 | CP016881 | 2,162,082 | 51.77 | 1 | 0 | 2361 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M08000 | CP016681 | 2,162,376 | 51.77 | 1 | 0 | 2357 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M08001 | CP016652 | 2,162,199 | 51.78 | 1 | 0 | 2359 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M09261 | CP016665 | 2,154,341 | 51.82 | 1 | 0 | 2351 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M09293 | CP016648 | 2,161,510 | 51.78 | 1 | 0 | 2366 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M10208 | CP009422 | 2,183,230 | 51.68 | 1 | 0 | 2434 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M12752 | CP016645 | 2,173,879 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2370 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22160 | CP016674 | 2,177,343 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2381 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22189 | CP016649 | 2,172,699 | 51.74 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22191 | CP016683 | 2,155,494 | 51.82 | 1 | 0 | 2337 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22718 | CP016627 | 2,173,408 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2367 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22722 | CP016663 | 2,172,888 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2370 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22740 | CP016679 | 2,172,899 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2366 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22745 | CP016657 | 2,163,399 | 51.77 | 1 | 0 | 2357 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22747 | CP016882 | 2,173,015 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2375 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22748 | CP016653 | 2,157,503 | 51.78 | 1 | 0 | 2359 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22759 | CP016669 | 2,168,308 | 51.74 | 1 | 0 | 2342 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22769 | CP016656 | 2,168,495 | 51.74 | 1 | 0 | 2344 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22772 | CP016655 | 2,173,607 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2366 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22783 | CP016671 | 2,180,570 | 51.64 | 1 | 0 | 2334 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22790 | CP016883 | 2,168,169 | 51.67 | 1 | 0 | 2360 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22797 | CP016884 | 2,193,498 | 51.76 | 1 | 0 | 2406 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22801 | CP016659 | 2,172,426 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2376 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22804 | CP016660 | 2,174,791 | 51.65 | 1 | 0 | 2325 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22809 | CP016647 | 2,182,171 | 51.63 | 1 | 0 | 2332 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22811 | CP016654 | 2,185,698 | 51.62 | 1 | 0 | 2342 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22819 | CP016646 | 2,173,686 | 51.65 | 1 | 0 | 2308 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22822 | CP016680 | 2,173,901 | 51.67 | 1 | 0 | 2334 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M22828 | CP016672 | 2,172,926 | 51.67 | 1 | 0 | 2318 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M23413 | CP016662 | 2,173,723 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M24705 | CP016682 | 2,175,832 | 51.66 | 1 | 0 | 2327 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M24730 | CP016658 | 2,175,362 | 51.74 | 1 | 0 | 2369 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25070 | CP016664 | 2,168,001 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25073 | CP016885 | 2,204,403 | 51.59 | 1 | 0 | 2415 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25074 | CP016886 | 2,211,323 | 51.56 | 1 | 0 | 2440 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25087 | CP016670 | 2,167,991 | 51.72 | 1 | 0 | 2365 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25419 | CP016678 | 2,189,560 | 51.71 | 1 | 0 | 2373 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25438 | CP016661 | 2,171,975 | 51.74 | 1 | 0 | 2369 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25456 | CP016677 | 2,173,106 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2371 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25459 | CP016673 | 2,173,115 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2376 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25462 | CP016666 | 2,174,042 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2378 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25472 | CP016668 | 2,170,146 | 51.72 | 1 | 0 | 2370 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25474 | CP016651 | 2,172,576 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2364 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M25476 | CP016676 | 2,168,191 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2370 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M27559 | CP016667 | 2,173,745 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2369 | 12 | 59 | |||

| M7124 | CP009419 | 2,179,483 | 51.73 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 15 | 61 | |||

| MC58 | AE002098 | 2,272,360 | 51.53 | 1 | 0 | 2412 | 12 | 59 | [67] | ||

| NM3682 | CP009420 | 2,196,674 | 51.64 | 1 | 0 | 2388 | 13 | 59 | |||

| NM3683 | CP009421 | 2,199,215 | 51.64 | 1 | 0 | 2384 | 14 | 61 | |||

| NM3686 | CP009418 | 2195,266 | 51.65 | 1 | 0 | 2365 | 12 | 59 | |||

| NZ-05_33 | CP002424 | 2,248,966 | 51.33 | 1 | 0 | 2385 | 12 | 59 | [66] | ||

| WUE2121 | CP012394 | 2,206,847 | 51.82 | 1 | 0 | 2403 | 12 | 59 | |||

| WUE_2594 | FR774048 | 2,227,255 | 51.84 | 1 | 0 | 2425 | 12 | 55 | [68] | ||

| Z2491 | AL157959 | 2,184,406 | 51.81 | 1 | 0 | 2335 | 12 | 58 | [69] | ||

| Nonpathogenic Neisseria species | |||||||||||

| N. lactamica 020-06 | FN995097 | 2,220,606 | 52.28 | 1 | 0 | 2372 | 12 | 59 | Diplococcus | Human | [70] |

| N. lactamica ATCC 23970 | KN046803 | 2,182,033 | 52.17 | 1 | 0 | 2294 | 12 | 57 | Diplococcus | Human | |

| N. lactamica Y92-1009 | CP019894 | 2,146,723 | 52.34 | 1 | 0 | 2298 | 12 | 58 | Diplococcus | Human | |

| N. mucosa C102 | GL635799 | 2,169,437 | 49.42 | 7 | 0 | 2132 | 3 | 54 | Diplococcus | Human, dog, duck, dolphin | |

| N. weaveri NCTC13585 | LT571436 | 2,188,497 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 2195 | 12 | 55 | Bacillus | Human, dog | |

| N. zoodegmatis NCTC12230 | NZ LT906434 | 2,552,522 | 50.94 | 1 | 0 | 2668 | 12 | 55 | Coccobacillus | Human, dog | |

| N. elongata ATCC 29315 | CP007726 | 2,256,647 | 54.26 | 1 | 0 | 2464 | 12 | 61 | Coccobacillus | Human | [71] |

Note. Latin name, accession number, genome size, GC content, number of scaffolds, number of plasmids, number of ORFs, rRNA, tRNA, morphology, natural host, and reference are listed.

According to a survey of some biological characters of Neisseria species, they exhibited far more diverse and widespread than previously recognized. For example, members in this genus have a spectrum of morphologies, including bacillus [50, 51], coccobacillus [52], and diplococcus [53], which exists in few bacteria genera. Furthermore, besides humans, some of the Neisseria species have been isolated from wide range of animals, such as dog, chimpanzee, and duck [54–56].

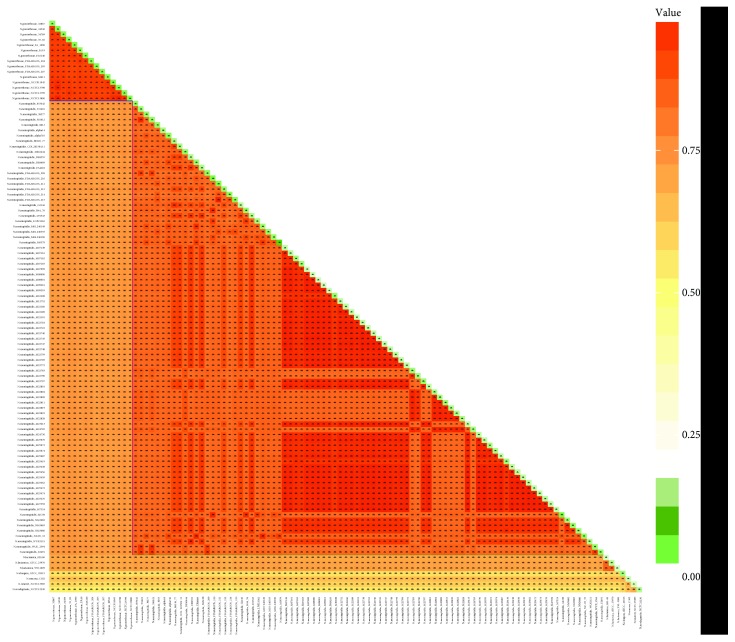

3.2. Homologous Proteome Analysis by Pairwise Comparisons

To estimate similarity of Neisseria species, the ratios of homologous clusters shared within each strain pair were calculated and visualized (Figure 1). The homologous ratio of different species ranged from 75.21% (N. gonorrhoeae NCTC13799 vs. N. meningitidis DE10444) to 52.55% (N. gonorrhoeae FDAARGOS 205 vs. N. zoodegmatis NCTC12230). Within N. meningitidis strains, the minimum homologous ratio was as low as 80.38% (N. meningitidis FDAARGOS_214 vs. N. meningitidis WUE 2594), indicating the high genetic diversity of this species. But for N. gonorrhoeae strains, they were generally above 90.75% (N. gonorrhoeae FA 1090 vs. N. gonorrhoeae FDAARGOS 205). The homologous ratio within genome ranged from 7.19% (N. meningitidis M0579) to 1.4% (N. weaveri NCTC13585) with average 2.74%, which showed the low redundancy of this genus strain genome composition. For N. gonorrhoeae, the homology ratio ranged from 4.49% (N. gonorrhoeae 34530) to 3.53% (N. gonorrhoeae 32867) with average 4.01%, which was greater than N. meningitidis.

Figure 1.

Homologous proteome analysis between different strain proteomes (orthologous) and within a strain proteome (paralogous). The percentages of orthologous and paralogous proteins were represented by orange and green, respectively. The color depth corresponded to the size of homologous proportion. The ratios of homologous were shown in both corresponding boxes and Table S1.

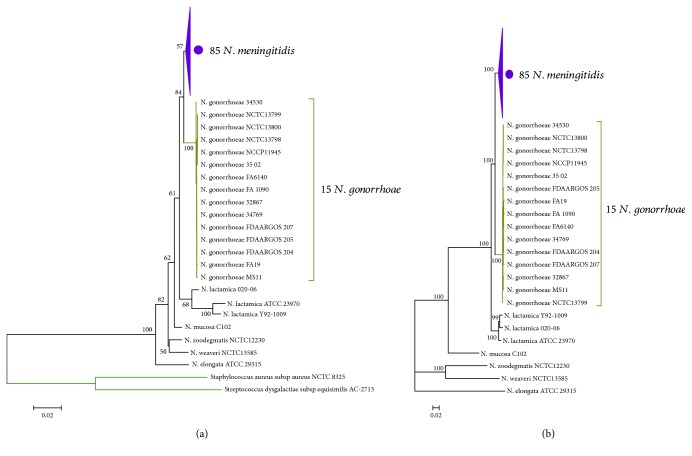

3.3. Phylogeny of the Genus Neisseria

It is medically interesting that the Neisseria species live in similar habitats but exhibit diverse phenotypes with respect to their interactions with hosts [5, 72, 73]. In order to better understand the evolutionary pattern of Neisseria species, a phylogenetic analysis of the genus Neisseria was performed, based on 16s rRNA (Figure 2(a)), and conserved amino acid sequences (Figure 2(b)), respectively. The two phylogenetic trees have identical topology, demonstrating the high reliability of the evolutional relationship. In addition, it is obvious that the tree based on single-copy gene dataset has maximum support for a single tree. In line with the previous studies [74, 75], using conserved gene dataset could yield a fully resolved phylogenetic tree with maximum support.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Neisseria strains included in this study. (a) Phylogenetic tree of 107 Neisseria strains constructed by neighbour joining (NJ) approach using 16s rRNA genes with the Kimura 2-parameter substitution model, bootstrapped ×1000 replicates. Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis AC-2713 were used as outgroups. Approval values of each major node were indicated. The subtree of N. meningitidis was compressed and denoted in purple. (b) Phylogenetic tree constructed by a maximum likelihood (ML) approach using concatenated single-copy gene dataset, bootstrapped ×100 replicates. Approval values of each major node were indicated. The subtree of N. meningitidis was compressed and denoted in purple.

For each tree, each species was clearly distinguished from others. The pathogens, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, were most closely related species and were adjacent to the distal end of the tree, and N. lactamica was the closest species to them. Interestingly, from rooted nodes to outer breaches, the morphologies of those species were bacillus (N. elongata, N. weaveri), coccobacillus (N. zoodegmatis), and diplococcus (N. mucosa, N. lactamica, N. gonorrhoeae, and N. meningitidis). This may suggest the process of morphological evolution of this genus member.

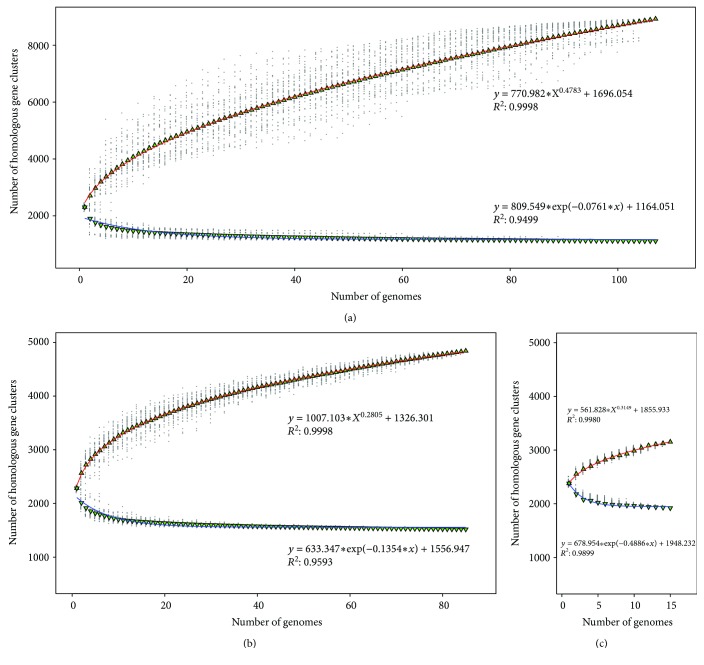

3.4. Core-Pangenome Analysis

In order to estimate the genome polymorphism of Neisseria species, the core and pangenome analyses were performed. For all the genomes in the study, the core genome size reached a plateau over 15 additions and finally kept stable at 1111, about half of the average gene content. However, the pangenome size quickly reached 8926 gene clusters, including 3493 singletons, with an average of 62 gene cluster additions for the following each genome addition (Figure 3(a)). Moreover, for 85 N. meningitidis genomes, the core and pangenome sizes were 1519 and 4841 gene clusters, respectively (Figure 3(b)). For 15 N. gonorrhoeae genomes, the core and pangenome sizes were 1921 and 3153 gene clusters, respectively (Figure 3(c)).

Figure 3.

Core and pangenome size evolution. Blue and red curves represent core and pangenome fitting curves for each group, respectively. (a) Core and pangenome of 107 Neisseria strain genomes using medians and a power law fit. (b) Core and pangenome of 85 N. meningitidis genomes using medians and a power law fit. (c) Core and pangenome of 15 N. gonorrhoeae genomes using medians and a power law fit.

In this study, the power law model was used to describe and predict the trend of Neisseria pangenome. The exponent size reflects the characters of pangenome. If it was greater than 0 and less than 1, the pangenome would be open; otherwise, it would be closed [36]. By power law regression of pangenome size, the fitting parameters B 1 kept within the range of 0 ~ 1 (0.4783, 0.2805, and 0.3149 for three groups, respectively), indicating that both Neisseria genus and Neisseria pathogens (N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae) had open genome. In order to adapt to a variety of environments, bacteria have to change their genomes, but living in monotone habitats would have smaller pangenome [76]. Most of the Neisseria species colonize on the mucosa, which may be the reason that the pangenome size is relatively small compared with other niche diversity species [77, 78].

In contrast to pangenome, the core genome size is relatively stable. However, the core genome sizes of NMS and NGS were greater than ATNS 408 and 810, respectively. This difference showed that there are some unique genes existing in Neisseria pathogens, which may be responsible for their pathogenesis characteristics.

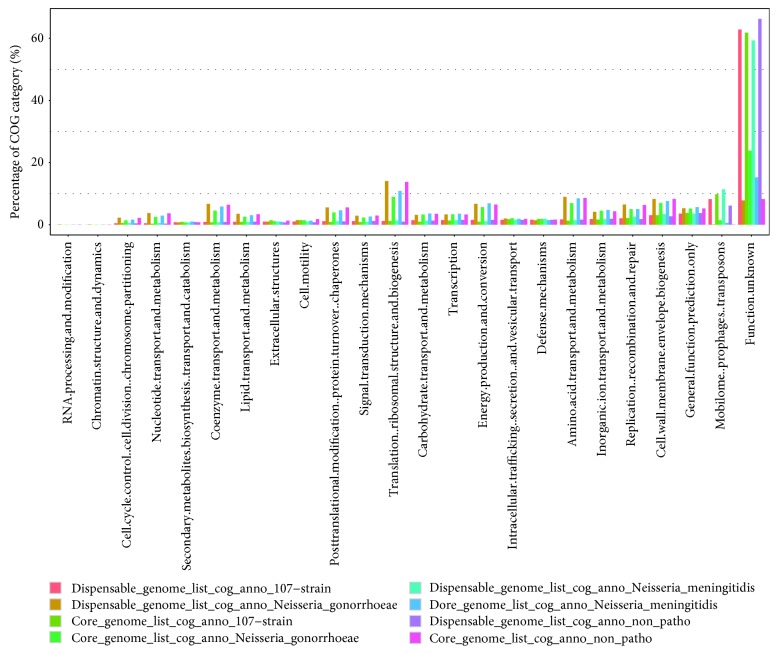

3.5. Functional Category of Core and Dispensable Genomes

The core genome is always responsible for the basic life process and shared phenotypic characteristics of a group of strains. On the contrary, the dispensable genome, which contributes to the species' own unique characteristics, is probably not essential to their basic life but provides selective advantages, including drug resistance and niche adaptation [79]. The core and dispensable genome sizes of ATNS, NMS, NGS, and NPNS are 1111/7815, 1517/4795, 1921/3786, and 1176/6598, respectively. In the present study, for the core and dispensable genomes of each strain group, functional category was performed using the COG database and divided into 24 subcategories, respectively (Figure 4). The unassigned gene families were merged into the category “function unknown.”

Figure 4.

Functional category of core and accessory genome components by COG database. Core and accessory genomes of ATNS, NMS, NGS, and NPNS were showed with different colors, respectively. The genes unassigned to any COG categories were combined into category “function unknown.”

As we expected, most of the core genome proteins for each group play a role of housekeeping. As shown in Figure 4, for the core genome of ATNS, NMS, NGS, and NPNS groups, these function categories that concentrated in were as follows: (1) translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (14.06%, 9.00%, 10.88%, and 13.78%, respectively); (2) amino acid transport and metabolism (8.99%, 6.97%, 8.49%, and 8.61%, respectively); (3) energy production and conversion (6.74%, 5.66%, 6.90%, and 6.50%, respectively); and (4) coenzyme transport and metabolism (6.74%, 4.55%, 5.86%, and 6.42%, respectively). These percentages were much greater than those of dispensable genome, and those functions are basic for life. On the contrary, for the dispensable genome of each group, mobilome: prophages, transposons (8.23%, 9.82%, 11.40%, and 6.14%, respectively) and replication, recombination, and repair (6.49%, 5.03%, 5.07%, and 6.34%, respectively) were the most plentiful categories.

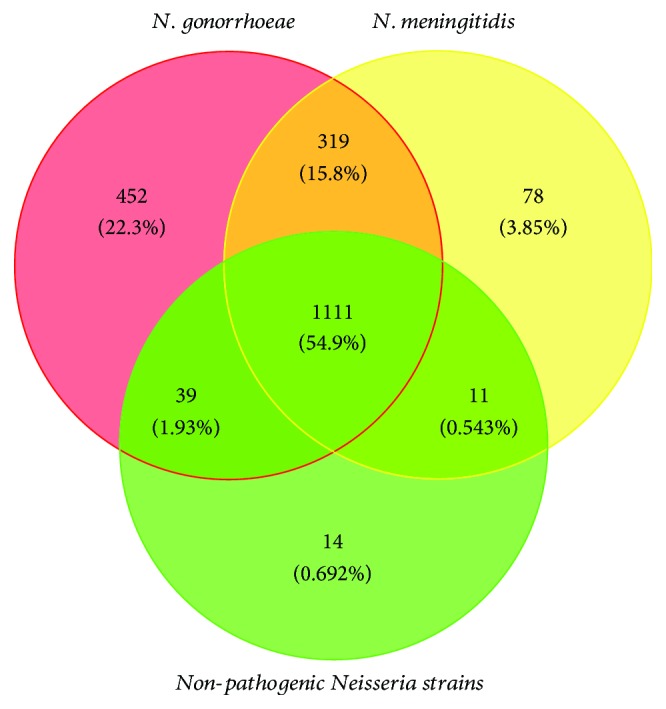

3.6. Identification and Annotation of Unique Genes for Each Neisseria Group

It is a reasonable assumption that unique genome contents of an organism are related directly to its unique phenotypes, which lead to the ability to adapt to unique and complicated conditions of its niche [80]. The number of unique genes for each group, including ATNS, NMS, NGS, and NPNS, was investigated and illustrated with a Venn diagram. As indicated in Figure 5, there are 1111 gene families shared by ATNS, which is in line with preceding core genome analysis results. Interestingly, as many as 319 gene families were unique genes for Neisseria pathogens (UGNP) but absent in NPNS. Moreover, NMS and NGS shared 11 and 39 gene families only with NPNS, respectively. Furthermore, there were 78 unique genes for NMS (UGNMS) and 452 unique genes for NGS (UGNGS). These unique genes of Neisseria pathogens may be the key factors which are related with their niche adaptability and pathogenicity. To some extent, the sample sizes of NGS and NPNS have an impact on reliability of the unique genes. More Neisseria samples should be sequenced in the future. In order to comprehend the roles of these unique genes in Neisseria pathogens, we investigated the gene functions of UGNP, UGNMS, and UGNGS.

Figure 5.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of shared gene families among NMS, NGS, and NPNS. Red, yellow, and green circles represent core genome of N. gonorrhoeae, N. meningitides, and nonpathogenic Neisseria strains, respectively. Their intersections represent the gene families they conserved.

The UGNP genes (Table S2) were enriched in COG categories C: energy production and conversion (average 7.98% for N. gonorrhoeae; average 8.24% for N. meningitidis, the same order with the following), E: amino acid transport (7.15%; 7.36%), and P: inorganic ion transport and metabolism (6.38%; 6.56%), significantly. Those genes are associated with basic metabolism, and many of them have been proved to be important factors surviving in their niche [81]. For example, Na+-transporting NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Na+-NQR, opr_724 for N. gonorrhoeae 32867; opr_285 for N. meningitidis MC58) was found conservative in plenty of bacteria pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae [82], Klebsiella pneumoniae [83], and Yersinia pestis [84]. This enzyme pumps Na+ across the cell membrane to generate a sodium motive force that can be used for solute import, ATP synthesis, and flagella rotation [85]. In V. cholerae, it was considered as an important factor to induce virulence factors [82]. Besides, many high-affinity iron uptake systems, which facilitate acquisition of the essential irons in the host, were found unique in Neisseria pathogens. ABC transporters, fbpA and fbpB, transcribed as an operon (opr_122 for N. gonorrhoeae 32867; opr_312 for N. meningitidis MC58), are necessary for the utilization of iron bound to transferrin or iron chelates [86, 87]. Furthermore, many other UGNP proteins, including Mn2+ efflux pump (MntP), multidrug resistance translocase (farB), and factor H-binding protein (fHbp), have been found to play important roles in niche adaptation [16, 88, 89].

For the UGNGS genes (Table S3), COG categories X: mobilome: prophages, transposons (average 6.43%), M: cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (average 4.62%), and P: inorganic ion transport and metabolism (average 3.89%) were enriched. Similarly, for the UGNMS genes (Table S3), COG categories X (average 11.39%), U: intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport (average 7.54%), and P (average 4.91%) were enriched. Substantial mobilome suggests that horizontal gene transfer may be widespread and frequent occurrence in N. gonorrhoeae genomes, which is beneficial for them to survive in changeable environmental conditions and develop resistance [90, 91]. In addition, most proteins of COG categories M, P, and U are membranes or membrane-associated proteins, such as glycosyltransferase involved in LPS biosynthesis (lgtB, lgtE: opr_1140 of N. gonorrhoeae 32867) and large exoprotein involved in heme utilization or adhesion (opr_252, opr_253, opr_256, opr_257 of N. meningitidis MC58), which play vital roles in interaction with the host and environment [92, 93]. What is more, the composition differences between UGNGS and UGNMS may be contributing greatly to their different tissue tropisms and pathogenic characteristics.

As detailed in Tables S2 and S3, a large number of genes that conserved in each species group were clustered into operons and had synergistic effects on its pathogenicity and niche adaptation. However, for each gene set, at least one-third genes (average 31.17% for UGNP, 52.38% for UGNGS, and 35.0% for UGNMS) have not been found the certain annotation information, indicating that the study for Neisseria species is not sufficient, and many more studies are still required to be done in the future.

3.7. SSR Locus Identification and COG Enrichment Analyses of Unique Genes of Neisseria Pathogens

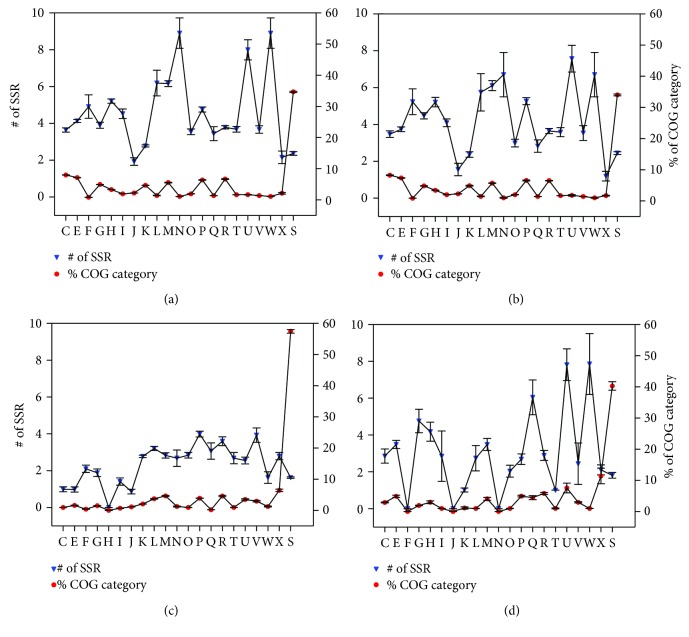

In many microbial pathogens, it has been found ubiquitous that SSRs were used in genes, which are mostly involved in host interactions, such as antigenic variation, to generate phase variation or protein sequence diversity, and this has been considered to contribute greatly to their virulence and adaptation [94, 95]. So, we investigated the distribution of SSR loci in each COG category for UGNP, UGNMS, and UGNGS genes (Figure 6), respectively.

Figure 6.

COG enrichment analysis of SSR loci in NMS and NGS unique genes. Subplots (a) and (b) represent the UGNP gene set characteristics based on Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis datasets, respectively. Subplot (c) represents the UGNGS gene set characteristics based on 15 Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains, and subplot (d) represents the UGNMS gene set characteristics based on Neisseria meningitidis strains. The red circular markers represent the average percentage of genes that enriched in the COG function categories (C–X) for each genome dataset. The blue inverted triangle markers represent the average number of SSR of each COG category gene for each genome dataset. The error bar represents the standard error of the mean for each gene group. Since the gene is absent from five COG categories (A, B, D, Y, and Z) in presented dataset, they have been omitted from the figures. Besides, the genes unassigned to any COG categories were combined into category S (function unknown). COG abbreviations: C: energy production and conversion; E: amino acid transport and metabolism; F: nucleotide transport and metabolism; G: carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H: coenzyme transport and metabolism; I: lipid transport and metabolism; J: translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis; K: transcription; L: replication, recombination, and repair; M: cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; N: cell motility; O: posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones; P: inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q: secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism; R: general function prediction only; T: signal transduction mechanisms; U: intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport; V: defense mechanisms; W: extracellular structures; X: mobilome: prophages, transposons; S: function unknown.

In UGNP genes (Figures 6(a) and 6(b)), the average numbers of SSR for about one half COG categories were greater than 4. It is interesting that W: extracellular structures (average 8.9 for N. gonorrhoeae; 6.7 for N. meningitidis, the same order with the following); U: intracellular trafficking, secretion (8.0; 7.6), and vesicular transport; N: cell motility (8.9; 6.7); and M: cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (6.2; 6.1) were the SSR-enriched genes. Obviously, most of these genes are membrane or related proteins (Table S1), such as type IV pilus proteins (pilC, pilP, and pilV) [96] and type V secretory pathway [97] (as detailed in Table S1), which are associated with virulence, niche adaptation, or other host interactions. Those genes have a high rate of mutation via slipped-strand mispairing at SSR loci during replication, which helps the Neisseria pathogens adapt to vastly different environments and evade host immune systems [19, 20, 94]. Additionally, the phase variation of these genes that encode surface-associated antigens is a big challenge to develop clinically efficient vaccine [98].

According to Figures 6(c) (based on UGNGS dataset) and 6(d) (based on UGNMS dataset), the average number of SSR of most COG categories of UGNMS is greater than UGNGS, especially in W: extracellular structures (1.6; 7.9), U: intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport (2.6; 7.8), and Q: secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism (3.1; 6.0). Eleven large exoproteins with average about 7 SSRs per gene (located in operons: opr_252, opr_253, opr_256, opr_257, opr_884, opr_885, and opr_886 of N. meningitidis MC58), which are involved in heme utilization or adhesion, were found in UGNMS. For UGNGS, eleven restriction-modification system-associated proteins, which are important to defense against foreign DNA, were identified as SSR-rich genes (average 4.5 SSRs per gene). Besides, phase variation of those DNA methyltransferases alters global DNA methylation patterns, which is associated with the epigenetic regulation of gene expression of multiple proteins that are involved in colonization, infection, and resistance to host defense, to aid N. gonorrhoeae adaptation to changing circumstance [99].

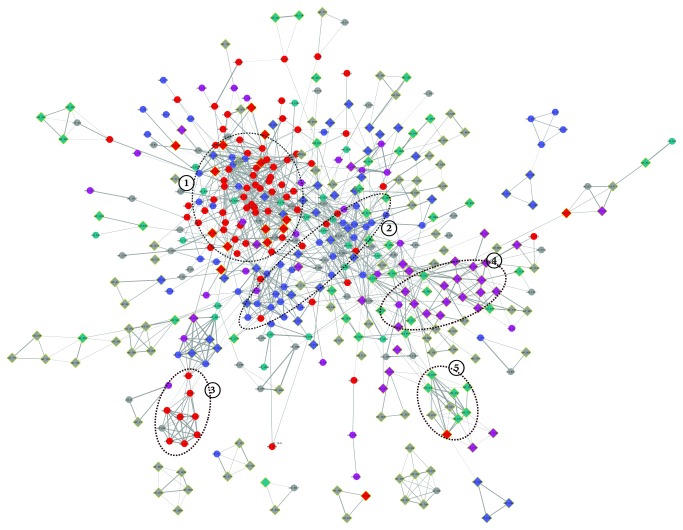

3.8. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analyses of Unique Genes

The unique genes of N. gonorrhoeae or N. meningitidis which is absent from NPNS were analyzed by STRING to construct the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network map. As showed in Figure 7, 489 proteins were contained in the N. gonorrhoeae PPI network map, including 244 UGNP proteins and 245 UGNGS proteins. Obviously, the network map had at least 5 major PPI clusters, and the proteins within them may interact with each other to function properly.

Figure 7.

Protein-protein interaction of UGNP and UGNGS. N. gonorrhoeae 32867 genome is used as reference. The names of nodes correspond to Table S1. Circular nodes represent the UGNP proteins, and diamond nodes with yellow margin represent the UGNGS proteins. Only the networks with the number of nodes greater than 3 were shown. The network edges represent the protein-protein associations, and their line thickness indicates the confidence of the association between corresponding nodes. The disconnected nodes are hidden in the map. Different colors reflect different protein function categories: red: basic substance transport and metabolism; purple: genetic information processing, including replication, transcription, and translation; blue: cellular processes, including cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis and cell motility; green: bacteria-environment interaction, including signal transduction, extracellular structures, and defense mechanism; grey, function unknown.

Most proteins of clusters 1 and 2 were UGNP proteins, and functional enrichment analysis indicated that they were involved in basic substance transport/metabolism and cellular processes associated with interacting networks, respectively. Specifically, ABC-type amino acid transport/signal transduction system (orf_439-orf_441, orf_2359-orf_2362), energy production and conversion-associated PPI network (orf_577, orf_778, orf_779, orf_1719, orf_1771, orf_1774, etc.), and so on were contained in cluster 1. They were important enzymes involved in signaling pathways and metabolic processes. In cluster 2, there was a cell wall polysaccharide biosynthesis system (orf_491, orf_1557, orf_2021, orf_2442-orf_2447, orf_2525, etc.), which was involved in immune system evasion, attachment to epithelial tissue, and an important mediator of the proinflammatory response [100]. Besides, the ion recognition and transport system (orf_264, orf_265, orf_331, orf_2462, orf_1513-orf_1515, orf_1585, etc.) have been proved crucial to the survival of Neisseria pathogens in vivo [101]. The cluster 3 codes for Na+-translocating NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (orf_1633-orf_1638, orf_1640, orf_1641, and orf_1659), which was found widely in pathogenic and conditionally pathogenic bacteria and shown to be important for the induction of virulence factors [82, 102].

However, most proteins of cluster 4 came from UGNGS and they were associated with DNA methylation and repairing (orf_8, orf_10, orf_361, orf_362, orf_431, orf_665, orf_825, orf_1109, orf_2226, etc.). They were related to the fine tuning of gene expression and DNA repair to aid N. gonorrhoeae adaptation to changing circumstance [99]. Moreover, cluster 5 was also unique in N. gonorrhoeae (orf_1074–orf_1077, orf_1079, orf_476, orf_477, and orf_479). Those genes code for restriction endonucleases. Weyler et al. found restriction endonucleases, which were released by intracellular Neisseria gonorrhoeae, damaged human chromosomal DNA, and distorted mitosis [103]. Besides, some other pathogenic-associated clusters were also found in Figure 7 network, such as the nitric oxide metabolic pathway (orf_1612-orf_1620) [104] and Tfp pilus assembly protein (orf_65, orf_129, orf_1665, orf_2249, orf_528, orf_1467, and orf_1757) [105].

For N. meningitidis, 252 proteins were contained in the PPI network map (Figure S1), including 203 UGNP proteins and 49 UGNMS proteins. The PPI clusters 1, 2, and 3 in N. meningitidis were found to be similar with N. gonorrhoeae. Moreover, cluster 4 associated with heme utilization or adhesion (orf_543, orf_545, orf_548, orf_551, orf_551, orf_556, orf_1971, orf_1983, and orf_1984) was found in Figure S1 network.

As analyzed above, plenty of proteins have been identified as crucial determinants in the context of colonization and invasive capability. Those unique proteins in N. meningitides and N. gonorrhoeae may account for the differences of pathogenicity and their niche adaptation. However, 167 proteins within Figure 7 and 52 proteins within Figure S1 still have no definite functional annotation at present. Their functions should be studied in the future.

4. Conclusions

N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, the closely related human pathogens with distinct habitat niches and pathogenic features, have been studied deeply. However, the genetic background of these differences has not yet been fully elucidated. In the present investigation, genus-wide comparative genomics analysis of Neisseria was performed to identify genes associated with pathogenicity and niche adaptation, based on sequenced genome of NMS, NGS, and NPNS. The core and dispensable genome sizes of ATNS, NMS, NGS, and NPNS are 1111/7815, 1517/4795, 1921/3786, and 1176/6598, respectively. The power law regression analysis of pangenome found that both Neisseria genus and each Neisseria pathogen have open pangenome (Figure 3). Most of the Neisseria species colonize on the mucosa but in various individuals, which may lead to the open pangenome but relatively small size compared with other niche diversity species [77, 78]. Secondly, the number of UGNP, UGNMS, and UGNGS is 319, 78, and 452, respectively. Functional analysis indicated that plenty of them have been proved as ones that playing significant roles in their pathogenicity and niche adaptation. Moreover, SSR locus identification and COG enrichment analysis of those unique genes showed that a large number of host interaction-associated proteins, especially membrane or related ones, were enriched with SSR. These results are in good agreement with previous observations [20]. Finally, the PPI analyses of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae unique proteins found that the majority of UGNP proteins were markedly clustered into two clusters (Figure 7, Figure S1). Functional enrichment analysis indicated that they are basic substance transport/metabolism and cellular processes associated with interacting networks, respectively. Some other clusters were also found, such as restriction-modification system, nitric oxide metabolic pathway, and heme utilization or adhesion system. Those proteins unique in N. meningitides and N. gonorrhoeae may well be vital to the niche adaptation and pathogenicity of the corresponding Neisseria species. However, 167 proteins with unknown function of N. gonorrhoeae and 52 of N. meningitidis exist in PPI analysis maps. They may interact with others and should be investigated in the future. What is more, the methods used in this study could be applied to other species to infer relationships between phenotypes and genotypes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Laboratory of Microbial Infection Research in Western Guangxi (Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities), Guangxi Key Discipline Fund of Pathogenic Microbiology (Grant no. kfkt2016021), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81760513), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 2017JJA10351), Basic Ability Promotion Project for Young and Middle-Aged College Teachers in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (Grant no. 2017KY0520 and no. KY2016LX252), Scientific Research Project of Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities (Grant no. yy2016bsky02), and Scientific Research Open Project of Key Laboratory in Guangxi's Universities (Grant no. kfkt2017005).

Abbreviations

- SSR:

Simple sequence repeat

- PPI:

Protein-protein interaction

- NPNS:

Nonpathogenic Neisseria strains

- rRNA:

Ribosomal RNA

- tRNA:

Transfer RNA

- ORFs:

Open reading frames

- MCL:

Markov clustering algorithm

- NJ:

Neighbour joining

- ML:

Maximum likelihood

- ATNS:

All of the tested Neisseria strains

- NMS:

N. meningitidis strains

- NGS:

N. gonorrhoeae strains

- COGs:

Clusters of Orthologous Groups

- VFDB:

Virulence factor database

- URHP:

Unique regions of H. pylori

- DOOR:

Database for prokaryotic operons

- eggNOG:

Evolutionary genealogy of genes: nonsupervised orthologous groups

- UGNP:

Unique genes for Neisseria pathogens

- UGNMS:

Unique genes for NMS

- UGNGS:

Unique genes for NGS.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

We consider that Qun-Feng Lu and De-Min Cao contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors. Qun-Feng Lu, De-Min Cao, and Ju-Ping Wang conceived and designed the study. Li-Li Su, Song-Bo Li, Guang-Bin Ye, and Xiao-Ying Zhu collected the data and participated in the analyses of Sections 2.6 and 2.8. De-Min Cao and Qun-Feng Lu performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of all authors. Qun-Feng Lu and De-Min Cao are the co-first authors. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: protein-protein interaction of UGNP and UGNMS.

Table S1: the ratio of homologous between genomes.

Table S2: (A) UGNP in N. gonorrhoeae 32867; (B) UGNGS in N. gonorrhoeae 32867.

Table S3: (A) UGNP in N. meningitidis MC58; (B) UGNMS in N. meningitidis MC58.

References

- 1.Knapp J. S. Historical perspectives and identification of Neisseria and related species. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1988;1(4):415–431. doi: 10.1128/CMR.1.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett J. S., Bratcher H. B., Brehony C., Harrison O. B., Maiden M. C. J. The Prokaryotes. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014. The genus Neisseria ; pp. 881–900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel U., Frosch M. The genus Neisseria: population structure, genome plasticity, and evolution of pathogenicity. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2002;264(2):23–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaura E., Keijser B. J. F., Huse S. M., Crielaard W. Defining the healthy “core microbiome” of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiology. 2009;9(1):p. 259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caugant D. A., Maiden M. C. J. Meningococcal carriage and disease—population biology and evolution. Vaccine. 2009;27(4):B64–B70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pizza M., Rappuoli R. Neisseria meningitidis: pathogenesis and immunity. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2015;23:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison L. H. Epidemiological profile of meningococcal disease in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;50(Supplement 2):S37–S44. doi: 10.1086/648963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy P. C., Sharyan A., Moghaddam L. S. Meningococcal vaccines: current status and emerging strategies. Vaccines. 2018;6(1) doi: 10.3390/vaccines6010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman L., Rowley J., Vander Hoorn S., et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One. 2015;10(12, article e0143304) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayor M. T., Roett M. A., Uduhiri K. A. Diagnosis and management of gonococcal infections. American Family Physician. 2012;86(10):931–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Report on Global Sexually Transmitted Infection Surveillance 2015. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards J., Jennings M., Seib K. Neisseria gonorrhoeae vaccine development: hope on the horizon? Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2018;31(3):246–250. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schielke S., Frosch M., Kurzai O. Virulence determinants involved in differential host niche adaptation of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae . Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 2010;199(3):185–196. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imhaus A. F., Duménil G. The number of Neisseria meningitidis type IV pili determines host cell interaction. The EMBO Journal. 2014;33(16):1767–1783. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hockenberry A. M., Hutchens D. M., Agellon A., So M. Attenuation of the type IV pilus retraction motor influences Neisseria gonorrhoeae social and infection behavior. mBio. 2016;7(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01994-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seib K. L., Scarselli M., Comanducci M., Toneatto D., Masignani V. Neisseria meningitidis factor H-binding protein fHbp: a key virulence factor and vaccine antigen. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2015;14(6):841–859. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1016915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis L. A., Carter M., Ram S. The relative roles of factor H binding protein, neisserial surface protein A, and lipooligosaccharide sialylation in regulation of the alternative pathway of complement on meningococci. Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(10):5063–5072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marri P. R., Paniscus M., Weyand N. J., et al. Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PLoS One. 2010;5(7, article e11835) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan P. W., Snyder L. A., Saunders N. J. Strain-specific differences in Neisseria gonorrhoeae associated with the phase variable gene repertoire. BMC Microbiology. 2005;5(1):p. 21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klughammer J., Dittrich M., Blom J., et al. Comparative genome sequencing reveals within-host genetic changes in Neisseria meningitidis during invasive disease. PLoS One. 2017;12(1, article e0169892) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tettelin H., Masignani V., Cieslewicz M. J., et al. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(39):13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delcher A. L., Bratke K. A., Powers E. C., Salzberg S. L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(6):673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rødland E. A., Staerfeldt H. H., Rognes T., Ussery D. W. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(9):3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe T. M., Eddy S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(5):955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders N. J., Jeffries A. C., Peden J. F., et al. Repeat-associated phase variable genes in the complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58. Molecular Microbiology. 2000;37(1):207–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali A., Soares S. C., Santos A. R., et al. Campylobacter fetus subspecies: comparative genomics and prediction of potential virulence targets. Gene. 2012;508(2):145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dongen S. Tech. Rep., Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science; 2000. A cluster algorithm for graphs. Information systems [INS] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enright A. J., Van Dongen S., Ouzounis C. A. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30(7):1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katoh K., Standley D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rokas A., Williams B. L., King N., Carroll S. B. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature. 2003;425(6960):798–804. doi: 10.1038/nature02053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talavera G., Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Systematic Biology. 2007;56(4):564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tettelin H., Riley D., Cattuto C., Medini D. Comparative genomics: the bacterial pan-genome. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2008;11(5):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatusov R. L., Fedorova N. D., Jackson J. D., et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4(1):p. 41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen H., Boutros P. C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1):p. 35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mao X., Ma Q., Zhou C., et al. DOOR 2.0: presenting operons and their functions through dynamic and integrated views. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(D1):D654–D659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(D1):D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L., Zheng D., Liu B., Yang J., Jin Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D694–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finn R. D., Attwood T. K., Babbitt P. C., et al. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(D1):D190–D199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruitt K. D., Tatusova T., Maglott D. R. NCBI reference sequence (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(Supplement 1):D501–D504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatusov R. L., Galperin M. Y., Natale D. A., Koonin E. V. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huerta-Cepas J., Szklarczyk D., Forslund K., et al. eggNOG 4.5: a hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D286–D293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandey A. K., Cleary D. W., Laver J. R., et al. Neisseria lactamica Y92–1009 complete genome sequence. Standards in Genomic Sciences. 2017;12(1):p. 41. doi: 10.1186/s40793-017-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander S., Fazal M. A., Burnett E., et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria weaveri strain NCTC13585. Genome Announcements. 2016;4(4) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00815-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollenbeck B. L., Gannon S., Qian Q., Grad Y. Genome sequence and analysis of resistance and virulence determinants in a strain of Neisseria mucosa causing native-valve endocarditis. JMM Case Reports. 2015;2(3) doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.000049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andersen B. M., Steigerwalt A. G., O'Connor S. P., et al. Neisseria weaveri sp. nov., formerly CDC group M-5, a gram-negative bacterium associated with dog bite wounds. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1993;31(9):2456–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2456-2466.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bøvre K., Holten E. Neisseria elongata sp. nov., a rod-shaped member of the genus Neisseria. Re-evaluation of cell shape as a criterion in classification. Journal of General Microbiology. 1970;60(1):67–75. doi: 10.1099/00221287-60-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ganière J. P., Escande F., André-Fontaine G., Larrat M., Filloneau C. Characterization of group EF-4 bacteria from the oral cavity of dogs. Veterinary Microbiology. 1995;44(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00110-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veron M., Thibault P., Second L. Neisseria mucosa (Diplococcus mucosus Lingelsheim). I. Bacteriological description and study of its pathogenicity. Annales de l'Institut Pasteur. 1959;97:p. 497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elliott D. R., Wilson M., Buckley C. M. F., Spratt D. A. Cultivable oral microbiota of domestic dogs. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(11):5470–5476. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5470-5476.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mugisha L., Köndgen S., Kaddu-Mulindwa D., Gaffikin L., Leendertz F. H. Nasopharyngeal colonization by potentially pathogenic bacteria found in healthy semi-captive wild-born chimpanzees in Uganda. American Journal of Primatology. 2014;76(2):103–110. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murphy J., Devane M. L., Robson B., Gilpin B. J. Genotypic characterization of bacteria cultured from duck faeces. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2005;99(2):301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abrams A. J., Trees D. L., Nicholas R. A. Complete genome sequences of three Neisseria gonorrhoeae laboratory reference strains, determined using PacBio single-molecule real-time technology. Genome Announcements. 2015;3(5) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01052-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chung G. T., Yoo J. S., Oh H. B., et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae NCCP11945. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190(17):6035–6036. doi: 10.1128/JB.00566-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng J., Yang L., Yang F., et al. Characterization of ST-4821 complex, a unique Neisseria meningitidis clone. Genomics. 2008;91(1):78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y., Yang J., Xu L., et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strain NMA510612, isolated from a patient with bacterial meningitis in China. Genome Announcements. 2014;2(3) doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00360-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rusniok C., Vallenet D., Floquet S., et al. NeMeSys: a biological resource for narrowing the gap between sequence and function in the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis . Genome Biology. 2009;10(10, article R110) doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schoen C., Blom J., Claus H., et al. Whole-genome comparison of disease and carriage strains provides insights into virulence evolution in Neisseria meningitidis . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(9):3473–3478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joseph B., Schneiker-Bekel S., Schramm-Gluck A., et al. Comparative genome biology of a serogroup B carriage and disease strain supports a polygenic nature of meningococcal virulence. Journal of Bacteriology. 2010;192(20):5363–5377. doi: 10.1128/JB.00883-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seib K. L., Jen F. E. C., Tan A., et al. Specificity of the ModA11, ModA12 and ModD1 epigenetic regulator N6-adenine DNA methyltransferases of Neisseria meningitidis . Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(8):4150–4162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bentley S. D., Vernikos G. S., Snyder L. A. S., et al. Meningococcal genetic variation mechanisms viewed through comparative analysis of serogroup C strain FAM18. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3(2, article e23) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Budroni S., Siena E., Hotopp J. C. D., et al. Neisseria meningitidis is structured in clades associated with restriction modification systems that modulate homologous recombination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(11):4494–4499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019751108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tettelin H., Saunders N. J., Heidelberg J., et al. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science. 2000;287(5459):1809–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schoen C., Weber-Lehmann J., Blom J., et al. Whole-genome sequence of the transformable Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A strain WUE2594. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(8):2064–2065. doi: 10.1128/JB.00084-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parkhill J., Achtman M., James K. D., et al. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature. 2000;404(6777):502–506. doi: 10.1038/35006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bennett J. S., Bentley S. D., Vernikos G. S., et al. Independent evolution of the core and accessory gene sets in the genus Neisseria: insights gained from the genome of Neisseria lactamica isolate 020-06. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):p. 652. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Veyrier F. J., Biais N., Morales P., et al. Common cell shape evolution of two nasopharyngeal pathogens. PLoS Genetics. 2015;11(7, article e1005338) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu G., Tang C. M., Exley R. M. Non-pathogenic Neisseria: members of an abundant, multi-habitat, diverse genus. Microbiology. 2015;161(7):1297–1312. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson M. B., Criss A. K. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to neutrophils. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kelleher P., Bottacini F., Mahony J., Kilcawley K. N., van Sinderen D. Comparative and functional genomics of the Lactococcus lactis taxon; insights into evolution and niche adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):p. 267. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3650-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bottacini F., O’Connell Motherway M., Kuczynski J., et al. Comparative genomics of the Bifidobacterium breve taxon. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):p. 170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Konstantinidis K. T., Serres M. H., Romine M. F., et al. Comparative systems biology across an evolutionary gradient within the Shewanella genus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(37):15909–15914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cao D.-M., Lu Q. F., Li S. B., et al. Comparative genomics of H. pylori and non-pylori Helicobacter species to identify new regions associated with its pathogenicity and adaptability. BioMed Research International. 2016;2016:15. doi: 10.1155/2016/6106029.6106029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qin Q. L., Xie B. B., Yu Y., et al. Comparative genomics of the marine bacterial genus Glaciecola reveals the high degree of genomic diversity and genomic characteristic for cold adaptation. Environmental Microbiology. 2014;16(6):1642–1653. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Medini D., Donati C., Tettelin H., Masignani V., Rappuoli R. The microbial pan-genome. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 2005;15(6):589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lefebure T., Stanhope M. J. Evolution of the core and pan-genome of Streptococcus: positive selection, recombination, and genome composition. Genome Biology. 2007;8(5, article R71) doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schoen C., Kischkies L., Elias J., Ampattu B. J. Metabolism and virulence in Neisseria meningitidis . Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2014;4:p. 114. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hase C. C., Mekalanos J. J. Effects of changes in membrane sodium flux on virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(6):3183–3187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bertsova Y. V., Bogachev A. V. The origin of the sodium-dependent NADH oxidation by the respiratory chain of Klebsiella pneumoniae . FEBS Letters. 2004;563(1-3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00312-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minato Y., Fassio S. R., Kirkwood J. S., et al. Roles of the sodium-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (Na+-NQR) on Vibrio cholerae metabolism, motility and osmotic stress resistance. PLoS One. 2014;9(5, article e97083) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verkhovsky M. I., Bogachev A. V. Sodium-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase as a redox-driven ion pump. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 2010;1797(6-7):738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Strange H. R., Zola T. A., Cornelissen C. N. The fbpABC operon is required for Ton-independent utilization of xenosiderophores by Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain FA19. Infection and Immunity. 2011;79(1):267–278. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00807-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khun H. H., Kirby S. D., Lee B. C. A Neisseria meningitidis fbpABC mutant is incapable of using nonheme iron for growth. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66(5):2330–2336. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2330-2336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schryvers A. B., Stojiljkovic I. Iron acquisition systems in the pathogenic Neisseria . Molecular Microbiology. 1999;32(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee E. H., Shafer W. M. The farAB-encoded efflux pump mediates resistance of gonococci to long-chained antibacterial fatty acids. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;33(4):839–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Perry J. A., Wright G. D. The antibiotic resistance “mobilome”: searching for the link between environment and clinic. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2013;4:p. 138. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Toussaint A., Chandler M. Bacterial Molecular Networks. Vol. 804. Springer; 2012. Prokaryote genome fluidity: toward a system approach of the mobilome; pp. 57–80. (Methods in Molecular Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Braun D. C., Stein D. C. The lgtABCDE gene cluster, involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, contains multiple promoter sequences. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186(4):1038–1049. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1038-1049.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stojijkovic I., Hwa V., Saint Martin L., et al. The Neisseria meningitidis haemoglobin receptor: its role in iron utilization and virulence. Molecular Microbiology. 1995;15(3):531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moxon R., Bayliss C., Hood D. Bacterial contingency loci: the role of simple sequence DNA repeats in bacterial adaptation. Annual Review of Genetics. 2006;40(1):307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou K., Aertsen A., Michiels C. W. The role of variable DNA tandem repeats in bacterial adaptation. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2014;38(1):119–141. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gault J., Ferber M., Machata S., et al. Neisseria meningitidis type IV pili composed of sequence invariable pilins are masked by multisite glycosylation. PLoS Pathogens. 2015;11(9, article e1005162) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Henderson I. R., Navarro-Garcia F., Desvaux M., Fernandez R. C., Ala'Aldeen D. Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2004;68(4):692–744. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.692-744.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maskell D., Frankel G., Dougan G. Phase and antigenic variation — the impact on strategies for bacterial vaccine design. Trends in Biotechnology. 1993;11(12):506–510. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(93)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seib K. L., Jen F. E. C., Scott A. L., Tan A., Jennings M. P. Phase variation of DNA methyltransferases and the regulation of virulence and immune evasion in the pathogenic Neisseria . Pathogens and Disease. 2017;75(6) doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mubaiwa T. D., Semchenko E. A., Hartley-Tassell L. E., Day C. J., Jennings M. P., Seib K. L. The sweet side of the pathogenic Neisseria: the role of glycan interactions in colonisation and disease. Pathogens and Disease. 2017;75(5) doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Genco C. A., Desai P. J. Iron acquisition in the pathogenic Neisseria . Trends in Microbiology. 1996;4(5):179–184. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hase C. C., Fedorova N. D., Galperin M. Y., Dibrov P. A. Sodium ion cycle in bacterial pathogens: evidence from cross-genome comparisons. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2001;65(3):353–370. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.353-370.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weyler L., Engelbrecht M., Mata Forsberg M., et al. Restriction endonucleases from invasive Neisseria gonorrhoeae cause double-strand breaks and distort mitosis in epithelial cells during infection. PLoS One. 2014;9(12, article e114208) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]