Abstract

Primary Ewing sarcoma (ES) or primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET) is a rare tumour in adults and primary renal involvement is extremely rare. Patients with renal ES or PNET respond to and would benefit from conventional ES treatment according to ES study protocols. Here, we report a case of a young woman, presenting with right flank pain and haematuria. After ultrasound and CT evaluation, a right middle pole renal mass was detected. The patient underwent radical right nephrectomy, and a grade 4 ES with peritoneal involvement was documented. Subsequently, the patient underwent adjuvant chemotherapy for 5 months. Follow-up 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan demonstrated bilateral cervical, hilar, mediastinal and retroperitoneal FDG-avid adenopathies associated with mild right-sided pleural effusion with no metabolic activity, signifying the role of PET/CT scan in tumour restaging.

Keywords: oncology, urological cancer, radiology

Background

Ewing sarcoma (ES) is rare renal tumour affecting young adults with rapid clinical progress and poor prognosis, secondary to delayed diagnosis and early-stage metastasis.1 2 However, kidney involvement is rarely seen and has worse prognosis.3 Fundamental challenge is the precise diagnosis allowing patient’s appropriate management, as this kind of kidney neoplasm mandates more aggressive treatment compared with other primary kidney tumours.4 It is mandatory to follow on these patients prospectively for obtaining more information regarding the biology of tumour and role of different therapeutic strategies considering specific tumour characteristics, for example, the relationship among tumour thrombosis and pulmonary metastasis.2

Case presentation

This is a 27-year-old woman who presented with right flank pain and haematuria. After ultrasound evaluation, a 69×60×95 mm renal mass was detected in the middle pole of the right kidney (figure 1) in which the patient underwent ultrasound-guided biopsy at the same time demonstrating poorly differentiated malignant cells. On subsequent CT scan with contrast, a right renal mass with no invasion to adrenal, liver, renal veins or inferior vena cava (IVC) was reported. The bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were reported normal on pathology evaluation. According to the imaging findings, the patient was staged as T2a, N0, M0 (stage II) renal cancer preoperatively.

Figure 1.

Heterogeneous mass measuring 69×60×95 mm in the middle pole of the right kidney on ultrasound examination.

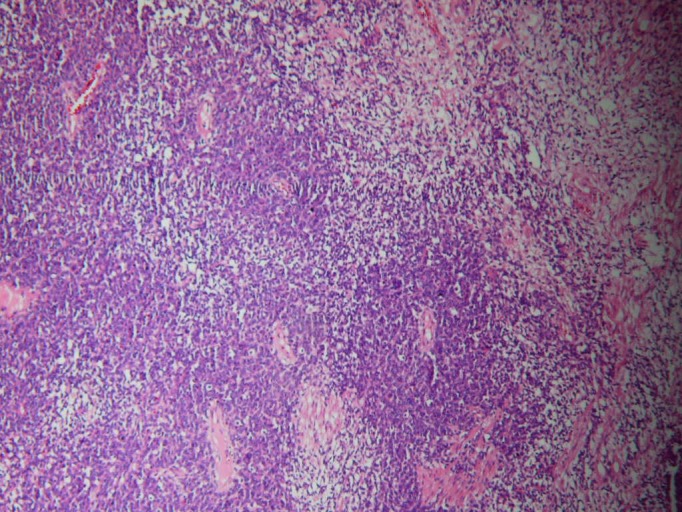

The patient underwent right-sided radical nephrectomy, and pathological evaluation was compatible with grade 4 ES associated with peritoneal involvement (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Small round oval cells with scanty cytoplasm and concentration around blood vessels (H&E staining, original magnification x10).

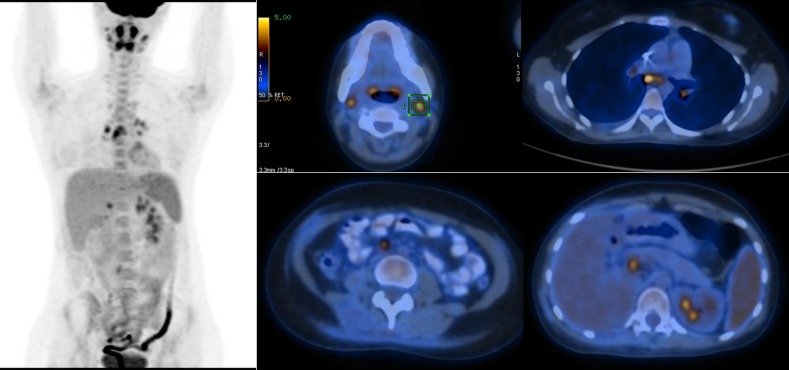

Adjuvant chemotherapy including combination of vincristine, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (VDC) followed by ifosfamide and etoposide (IE) was performed after radical nephrectomy. After 5 months, the patient underwent 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT scan in June 2018 for the purpose of restaging and bilateral cervical, hilar, mediastinal and retroperitoneal FDG-avid adenopathies in addition to mild right-sided pleural effusion with no metabolic activity were encountered (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hypermetabolic cervical, mediastinal and retroperitoneal metastatic lymph nodes.

Differential diagnosis

The major differential diagnoses for renal ES include wide range of neoplasms including malignant lymphoma, renal neuroblastoma, Wilms’ tumour, small-cell osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and variant of renal ES with neural differentiation.5 6 In this patient, the H&E staining demonstrated small round oval cells with scanty cytoplasm and concentration around blood vessels which is suggestive for sarcomatous tumoural involvement of kidney tissue.

Treatment

Right-sided radical nephrectomy, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy including combination of VDC followed by IE.

Outcome and follow-up

18F-FDG PET/CT scan in our department demonstrated bilateral cervical, hilar and mediastinal and retroperitoneal hypermetabolic adenopathies and non-FDG-avid mild right-sided pleural effusion.

The patient is currently alive and is considered for additional chemotherapy according to systemic metastases visualised on PET/CT scan.

Discussion

On the study published by Tariq et al, a total of 48 cases (18 articles) of renal ES were analysed with a mean age of 30.4 years. The mean survival was 26.14 months with a lower median survival in patients with advanced metastatic disease. Thirty-six patients presented with acute flank pain mimicking renal colic with or without hydronephrosis and a renal mass on imaging studies. Another less common presentation was haematuria which was found in 15 patients. Despite aggressive treatment, the prognosis of renal ES was poor. The most common sites of metastasis were the lungs, followed by the liver and bone.1

In another study published by Zöllner et al, 24 patients with renal primary tumour with median age of 24.9 years were evaluated. The most common presenting symptoms included abdominal pain, haematuria and palpable mass. Laboratory findings were unremarkable. Fifteen patients presented with localised disease in kidney, four patients were in advanced stage with lung metastasis and five other patients presented with multiorgan metastatic disease including lungs, bone, liver, lymph node or other metastatic sites. Information about tumour thrombus was available for 16 patients. Seven patients displayed tumour thrombi in the inferior vena cava, four of which presented with initial pulmonary metastases (more than half). Two more patients presented with a renal vein thrombus only.5

In another case report by Ozturk, he presented a case of a 38-year-old woman with incidental left renal mass. MRI revealed a centrally located hypervascular renal mass with a diameter of 6 cm with non-homogenous contrast enhancement containing necrotic and calcific areas. The patient was diagnosed with primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET)/EWS by histopathological examination following radical nephrectomy, and subsequently a para-aortic lymph node metastasis was found on 18F-FDG PET/CT.7 Lai et al reported usefulness of FDG PET/CT scan for detection of tumour thrombosis in six patients including EWS.8 Srivastara et al also reported a rare case of PNET of breast and discussed complementary role of FDG PET/CT and MRI in assessing local tumour resectibility and presence of metastatic disease.9

The fundamental challenge remains the proper diagnosis and its confirmation for a patient’s adequate and timely treatment, as this tumour requires more extensive therapy compared with other primary renal neoplasms, for example, Wilms’ tumour.10

In conclusion, PNETs and ES are invasive neoplasms and early metastasis is their significant characteristic (25%–50% demonstrate evidence of metastasis at presentation). Therefore, these tumours are considered systemic disease, and metastases may involve normal-appearing organs and lymph nodes.

Although ES cases have been reported in literature frequently, the strong and different point of current case report is the detection of metastases in the tissues without significant anatomic distortion which is enhanced by means of FDG PET/CT scan, a combination of anatomic and functional images.

Learning points.

Primary Ewing sarcoma (ES) is a rare tumour in adults.

Patients with renal ES/primitive neuroectodermal tumour respond to and benefit from conventional ES treatment according to ES study protocols.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scan is a valuable tool to evaluate possible metastatic sites and treatment response in patients and also can guide further treatment strategy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our best regards towards Masih Daneshvari Hospital and the PET/CT department for all helps and contributions.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: AD: project conceptualisation, manuscript edition. SA: manuscript drafting and data search. PM: final review and approval. MP: pathology review.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hakky TS, Gonzalvo AA, Lockhart JL, et al. . Primary Ewing sarcoma of the kidney: a symptomatic presentation and review of the literature. Ther Adv Urol 2013;5:153–9. 10.1177/1756287212471095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coffin CM, Dehner LP, O’Shea PA. Paediatric soft tissue tumours: a clinical pathological and therapeutic approach. 15 Baltimore, MD, USA: Williams & Wilkins, 1997:80–132. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parham DM, Roloson GJ, Feely M, et al. . Primary malignant neuroepithelial tumors of the kidney: a clinicopathologic analysis of 146 adult and pediatric cases from the national wilms’ tumor study group pathology center. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venkitaraman R, George MK, Ramanan SG, et al. . A single institution experience of combined modality management of extra skeletal Ewings sarcoma. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:3–4. 10.1186/1477-7819-5-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zöllner S, Dirksen U, Jürgens H, et al. . Renal ewing tumors. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2455–61. 10.1093/annonc/mdt215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kang SH, Perle MA, Nonaka D, et al. . Primary Ewing sarcoma/PNET of the kidney: fine-needle aspiration, histology, and dual color break apart FISH Assay. Diagn Cytopathol 2007;35:353–7. 10.1002/dc.20642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ozturk H. Peripheral neuroectodermal tumour of the kidney (Ewing’s sarcoma): restaging with (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:39–E44. 10.5489/cuaj.2286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lai P, Bomanji JB, Mahmood S, et al. . Detection of tumour thrombus by 18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging. Eur J Cancer Prev 2007;16:90–4. 10.1097/01.cej.0000220641.46470.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Srivastava S, Arora J, Parakh A, et al. . Primary extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor of breast. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2016;26:226–30. 10.4103/0971-3026.184408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casella R, Moch H, Rochlitz C, et al. . Metastatic primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the kidney in adults. Eur Urol 2001;39:613–7. 10.1159/000052514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]