Abstract

Background

User charges are widely used health financing mechanisms in many health systems in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to insufficient public health spending on health. This study systematically reviews the evidence on the relationship between user charges and health outcomes in LMICs, and explores underlying mechanisms of this relationship.

Methods

Published studies were identified via electronic medical, public health, health services and economics databases from 1990 to September 2017. We included studies that evaluated the impact of user charges on health in LMICs using randomised control trial (RCT) or quasi-experimental (QE) study designs. Study quality was assessed using Cochrane Risk of Bias and Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—of Intervention for RCT and QE studies, respectively.

Results

We identified 17 studies from 12 countries (five upper-middle income countries, five lower-middle income countries and two low-income countries) that met our selection criteria. The findings suggested a modest relationship between reduction in user charges and improvements in health outcomes, but this depended on health outcomes measured, the populations studied, study quality and policy settings. The relationship between reduced user charges and improved health outcomes was more evident in studies focusing on children and lower-income populations. Studies examining infectious disease–related outcomes, chronic disease management and nutritional outcomes were too few to draw meaningful conclusions. Improved access to healthcare as a result of reduction in out-of-pocket expenditure was identified as the possible causal pathway for improved health.

Conclusions

Reduced user charges were associated with improved health outcomes, particularly for lower-income groups and children in LMICs. Accelerating progress towards universal health coverage through prepayment mechanisms such as taxation and insurance can lead to improved health outcomes and reduced health inequalities in LMICs.

Trial registration number

CRD 42017054737.

Keywords: user charges, user fees, cost sharing, population health, health systems financing

Key questions.

What is already known?

User charges are widely used as a health financing mechanism in many low-income and middle-income countries, but the relationships between user charges and health outcomes have not been examined in a systematic review.

What are the new findings?

Improved access to healthcare due to a lower level of out-of-pocket expenditure from user charges was identified as a potential explanatory factor for improved health outcomes.

This systematic review found that reducing user charges was associated with improvements in health outcomes, especially among children and lower-income populations.

What do the new findings imply?

These findings highlight the importance of shifting away from user charges to finance universal health coverage towards use of prepayment through taxation and insurance contributions.

Reducing user charges for vulnerable populations can reduce financial hardship from healthcare payments, which in turn improves health outcomes and promotes health equity.

Introduction

Achieving universal health coverage (UHC)—defined as ensuring timely access to quality healthcare without financial hardship1—is a target for the Subtainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3). UHC has also been identified as an important instrument for countries to attain other key SDGs, including poverty reduction (SDG 1), reduced gender inequality (SDG 5), inclusive economic growth (SDG 8) and reduced inequalities (SDG 10).2 3

Alternative approaches to finance UHC and their associated impacts on the SDGs is an emerging area of research. Among the four financing strategies to achieve UHC recommended by WHO (ie, increasing efficiency of taxation, reprioritising government budgets towards health, innovative financing, increasing development assistance for health), risk pooling with prepayment is one of the most promising strategies.4 5 However, in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), user charges, which are fees incurred at the point of care, are widely used as a health financing mechanism to modulate demand for healthcare and to supplement shortfalls in public spending on health.6 7 Recent statistics have shown that out-of-pocket spending (including user charges) accounts for a large proportion of total health expenditure in many of the most populous LMICs, including Brazil (higher than 28%), China (higher than 32%), Ethiopia (higher than 38%), India (higher than 65%), Indonesia (higher than 48%), Nigeria (72%) and Pakistan (higher than 66%).8 9 Out-of-pocket spending can have an impoverishing impact, especially among low-income groups.4 10

There is growing attention to the relationship between user charges and population health outcomes in LMICs. Evidence from high-income countries (HICs) shows that reducing user charges can improve population health outcomes due to more timely treatment and enhanced adherence to medication.11–13 However, there may be dangers in extrapolating findings from HICs to LMICs where health systems are more fragmented and the cost of healthcare may be a greater barrier for patients to access services.8 14

The relationship between user charges and access to healthcare has been well documented; however, less is known about the impact of user charges on health outcomes in LMICs. The aim of this study is to review and synthesise evidence from robust empirical studies, such as randomised control trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental (QE) studies, on the impact of user charges on health outcomes in LMICs and explore potential explanatory mechanisms for the associations identified.

Methods

We followed the methods detailed in a peer-reviewed systematic review protocol that is registered with PROSPERO (registration CRD 42017054737).

Search strategy

In September 2017, we conducted searches of electronic medical and economics databases (MEDLINE, Econlit, Scopus, JSTOR, WHO Library Database, World Bank e-Library) to locate studies about the impact of user charges on health outcomes in LMICs. We included all types of health outcomes with quantitative measures, with the search strategy based on a combination of three sets of keywords—(1) health, (2) synonyms of user charges and (3) a list of LMICs (detailed search strategy can be found in online appendix—database search strategy):

Synonyms of health.

User charges: “reimbursement”, “copayment”, “cost sharing”, “coinsurance”, “deductible”, “user charge”, “user fee”, “out-of-pocket”, “health insurance”, “medical insurance”.

LMICs: “Low and middle income country”, “Asia”, “South East Asia”, “Central Asia”, “sub-Saharan”, “Africa”, “South America”, “Latin”, “low-income country”, “middle-income country”, “developing country”, “under developed” and all LMICs listed in the World Bank website in year of 2016.15

The searches were restricted to studies written in English (peer-reviewed articles, working papers, conference papers and reports) published from January 1990 to September 2017. We also carried out additional literature searches by appraising reference lists of the studies identified.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

User charges were defined as direct payments made at the time of health service use,16 with any possible combination of fees from registration, consultation, drugs and medical supplies, treatment, hospitalisation, delivery fees, laboratory tests or other health services provided in public or publicly subsidised sectors. The charges could be paid based on each visit to a healthcare provider or for treatment of the whole episode of illness.7

Studies were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in table 1. All study populations were eligible. For outcomes, we considered both self-reported and clinically measured health outcomes in relation to both increases and decreases in user charges. As eligible interventions, only studies which examined changes in the levels of user charges (in either direction or magnitude) were included, while studies focusing on the impact of health insurance without explicitly examining changes in user charges were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection based on PICOS

| Selection criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Population | LMICs | Non-LMICs |

| Intervention | Isolated demand-side user charge changes attributed to financing policy or health insurance scheme for health services, including increased, decreased, introduction and abolition of user charges. The study could either mention direction or magnitude changes in amount or proportion of user charges | Examined complex intervention: both of demand-side and supply-side intervention Examined concurrent policy changes Only examined the impact of health insurance without explicitly mentioning changes in user charges |

| Comparator | Individuals or communities in LMICs that were not exposed to user charge changes during the period of study | None |

| Outcome | All types of health outcomes (eg, general health status, mortality, non-communicable disease, infectious disease, nutritional and anthropometric measurements) | Only assessed health service use |

| Study design | Quasi-experimental study design: difference-in-differences, propensity score matching, instrumental variable, regression discontinuity, interrupted time series and any combination of these designs Randomised control trial, cluster-randomised control trial |

Cross-sectional study, simple before–after comparison, qualitative study, cost–benefit/cost-effectiveness analysis, systematic review, meta-analysis, commentary |

LMIC, low-income to middle-income country.

To synthesise findings from robust evidence, we only included studies with either QE or RCT study designs to control for confounding and bias. For example, estimated policy effects could be biassed if self-selection exists, when individuals who expect to have high healthcare use choose insurance schemes with lower user charges.7 Therefore, the relationship between the levels of user charges, healthcare use and health outcomes may have elements of reverse causality.17 A broad definition of QE was considered which included difference-in-differences (DID), propensity score matching (PSM), instrumental variable (IV), regression discontinuity (RD) and interrupted time series (ITS).18–20 To isolate changes in health outcomes attributing to user charges, we removed studies that evaluated multifaceted policy changes (from both demand or supply sides) or consisted of several concurrent policy changes which precluded assessment of individual policy impacts.

One reviewer (VMQ) independently reviewed titles and abstracts and discussed with another reviewer (JTL) on the uncertain studies. Subsequently, full texts were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers (VMQ and JTL). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (TH).

Quality assessment

Quality assessments were dependent on risk of bias for each study. We used a modified ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies—of Interventions) tool21 for studies adopting a QE design. First, we assessed the risk of biases (two relating to pre-intervention, one relating to at-intervention, four relating to post-intervention) for each QE to reach an overall risk of bias (ie, low/moderate/serious/critical/no information). We graded the quality of each QE as high (low risk of bias), moderate (moderate risk of bias) or low (serious risk of bias or below) based on the overall risk of bias.

We used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to assess seven domains of biases for studies adopting an RCT design. The quality of the RCT was then graded high (low risk of bias for more than five domains), moderate (high risk of bias for two domains) or low (high or unclear risk of bias for more than two domains).22

Data extraction and synthesis

The data extracted from selected articles consisted of the study setting, detail on the change in user charge policy, study design, data sources, follow-up period and key findings on health outcomes. We also examined secondary outcomes, such as access to healthcare and levels of financial protection, where possible.

Due to heterogeneity in policy settings, countries, study designs, intervention and outcomes, meta-analysis was not feasible. We conducted a narrative review and reported effects, stratified by different types of health outcomes. We also outlined effects for secondary outcomes to explore possible mechanisms of action between user charges and health outcomes. We analysed the impact of user charges policies on health by different population groups, such as low-income populations and children, to explore whether impact varied by population groups.

Additionally, we undertook an analysis to understand the evidence gap by graphically displaying the knowledge gap of the findings in type of health outcomes and population studied, and quality of the studies.

Results

Study characteristics

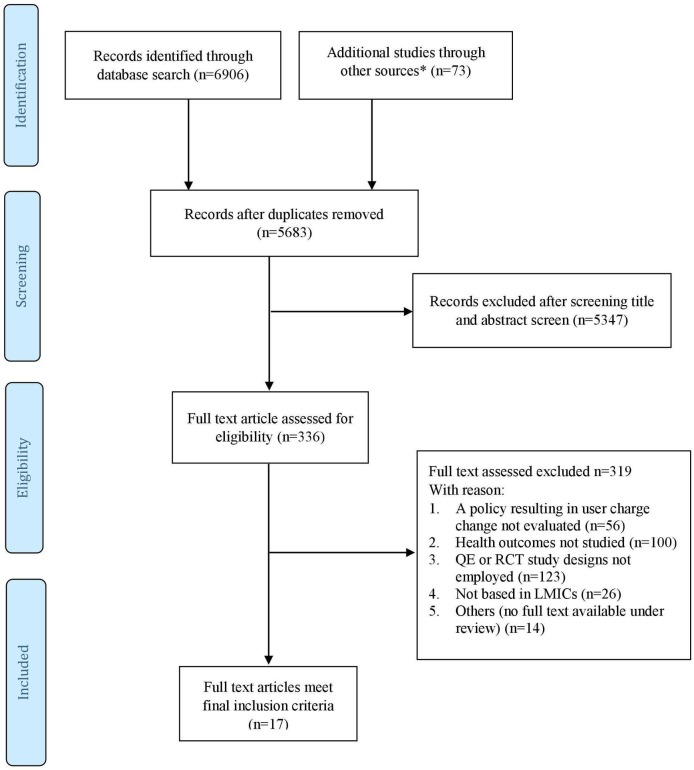

We identified 6902 citations from bibliographic databases and an additional 73 from other sources. After removal of duplicates, 5683 unique citations were screening by title and abstract, and 336 full texts were sourced. Of these studies, 319 studies were excluded for the following reasons: a policy resulting in user charge change not evaluated (56 studies); health outcomes not studied (100 studies); QE or RCT study designs not employed (123 studies); not based in LMICs (26 studies); and other reasons such as duplicate studies, unrelated topics, under review or no full text available (14 studies). Seventeen studies met the final inclusion criteria. Figure 1 provides details of the process of study identification.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of study identification in review of the effects of user charges on health in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). *Other sources include WHO Library Database, World Bank e-Library and manually searched references of the included papers. QE, quasi-experimental; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

The 17 included studies were conducted in 12 LMICs: five upper-income to middle-income countries—China (two studies), Georgia (one study), Jamaica (one study), South Africa (one study) and Mexico (two studies); five LMICs—India (three studies), Vietnam (three studies), the Philippines (one study), Ghana (one study) and Kenya (one study); and two low-income countries—Senegal (one study) and Nepal (one study). Of the 17 studies, 14 were published after 2010. One study was an RCT, nine used DID design, two employed RD, three used PSM, one used DID design with PSM (DID-PSM) and one used IV regression. More details of study characteristics are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary characteristics of included studies (N=17)

| Characteristic | Asia | America | Africa | Europe | Total |

| Study published year | |||||

| 1990–2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2001–2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 2011–2017 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Study design | |||||

| DID | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| RD | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| PSM | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| IV | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| PSM-DID | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| RCT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Changes in user charges | |||||

| Increasing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Decreasing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Introducing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abolishing | 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 15 |

| Economy*† | |||||

| Upper middle income | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lower middle income | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Low income | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Health outcomes‡ | |||||

| General health | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Mortality | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Infectious disease–related outcomes | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Chronic condition–related outcomes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Nutritional outcomes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Age group of the study population | |||||

| General | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Women | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Children | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Elderly | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Social economic status of the study population§ | |||||

| Poor | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| General | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

*According to World Bank country classification 2016.

†The multicountry analysis consisted of three countries: two middle-income and one low-income countries.

‡The sum of health outcome category may be double entered because some studies evaluated more than one type of health outcome. America in this review included both South and Latin America.

§As defined in the context of the study.

DID, difference-in-difference; IV, instrumental variable; PSM, propensity score matching; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RD, regression discontinuity.

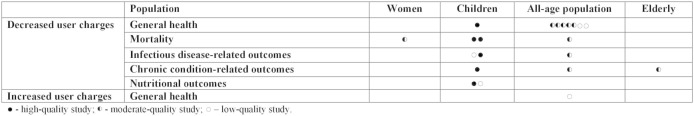

A range of health outcomes were studied and categorised into five groups (figure 2): general health outcomes (nine studies), mortality (four studies), infectious disease–related outcomes (three studies), chronic condition–related outcomes (three studies), and nutritional and anthropometric outcomes (two studies).

Figure 2.

Intervention focus and outcome studies.

Changes in user charge policies were classified as removing user charges (15 studies), reducing user charges (one study) or increasing user charges (one study). Thirteen studies examined user charges in primary or outpatient services, while four examined user charges in secondary and tertiary care. The majority (14/17) of the studies examined relevant secondary outcomes on access to healthcare and levels of financial protection. The median follow-up period from intervention to the last observation was 45 months, with a range of 12–144 months. Studies on chronic condition–related outcomes had the longest median follow-up period of 72 months.

Quality of included studies

Overall study quality was moderate, with four studies of high quality, 10 of moderate quality and three of low quality. Areas of potential bias that many QEs failed to address were potential selection bias (six studies) with the possibility selection could be related to intervention status or outcome, and potential recall or misclassification bias (seven studies) as using self-reported health outcomes may have affected the ‘measurement of outcomes’. The quality of the only RCT study included was rated high with nearly all domains assessed at low risk except the domain ‘performance bias’, which was high risk as participants were un-blinded to the intervention which may contaminate the results (online supplementary table 1).

bmjgh-2018-001087supp001.pdf (234.9KB, pdf)

Findings on the relationships between user charges and health outcomes

General health outcomes

Nine studies23–31 evaluated the impact of user charges on general health (three in Vietnam, two in China, two in India, one in Jamaica, one in Georgia) (table 3). In terms of outcomes measured, three studies measured changes in the number of sick days30 32 33 and six in self-reported health status31 34–38 (online supplementary table 2). Eight studies examined the impact of reducing user charges and one focused on the impact of increasing user charges. Five out of eight studies (based in Vietnam, India and Jamaica23 24 26 29 30) showed that reducing user charges was associated with fewer sick days and improved self-reported well-being. Nguyen and Wang,26 a high-quality study, evaluated the Free Care for Children under Six policy in Vietnam, where they found removing user fees from inpatient and outpatient services for non-poor children under 6 years old associated with a 26% reduction in self-reported number of sick days, along with a significant increase in the use of secondary care, and a substitutional reduction in the use of tertiary care. Sood and Wagner, a moderate-quality study, evaluated the impact of the Indian Vajpayee Arogyashree Scheme (VAS) programme which provided free tertiary care for the poor in the state of Karnataka,24 where they found that removing user charges was associated with a significant improvement on post-hospitalisation well-being, accompanied by 4.4% more frequent treatment seeking by VAS participants and 16.5% reduction in re-hospitalisation subsequently.

Table 3.

Summary of the impact of user charges on certain health outcomes and secondary outcomes

| Study | Intervention | Population | Improved general health | Improved mortality outcomes | Improved infectious disease– related outcomes |

Improved chronic disease– related outcomes |

Improved nutritional outcomes | Increased access to primary care or outpatient | Increased access to secondary care | Increased access to tertiary care or inpatient | Improved financial protection | Notes | Study quality |

| Decreased user charges | |||||||||||||

| Nguyen and Wang26 | Before: user fees in the public hospitals were a major financial burden After: free care including inpatient and outpatient services, and associated laboratory tests and generic medicines |

Vietnam—non-poor children under 6 years old | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | There was a ‘substitution’ effect between increased use of secondary hospitals and decreased use of tertiary hospitals | High |

| Sood and Wagner24 | Before: unspecified After: no premiums or copayments at the point of tertiary care at both private and public hospitals in 2010–2012 |

India— poor population |

↑ | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | There was a ‘substitution’ effect between increased use of tertiary care and readmission | Moderate |

| Beuermann23 | Before: pay out-of-pocket fees (amount unspecified) After: no user fee for healthcare services (ie, doctor’s consultation, diagnosis, surgeries) |

Jamaica— general population |

↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Improved general health had a positive labour supply effect with increased labour hours | Moderate |

| Bauhoff et al 27 | Before: unspecified After: comprehensive benefit package with few coverage limits and no copayments for beneficiaries; basic universal package subjected to copayments of 25%–50% for non-MIP population |

Georgia— poor population |

→ | – | – | – | – | → | – | → | ↑ | The reduction of user charges provided financial protection, but little impact on service use and self-reported health status | Moderate |

| Guindon25 | Before: unspecified After: no deductibles for most outpatient and inpatient care at government facilities and drugs on the Ministry of Health list, financed from general government revenues at both national (75%) and provincial (25%) levels |

Vietnam— poor population |

→ | – | – | – | – | → | – | ↑ | – | Low | |

| Aggarwal29 | Before: full cost for treatment After: free outpatient diagnosis for all types of medical events and up to 50% discount on all laboratory tests |

India—disadvantaged rural general population | ↑ | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | ↑ | The author suggested that decreased user charges increased access to healthcare services and improved financial protection, which should translate into better health outcomes | Moderate |

| Yiqiu Wang et al 28 | Before: unspecified After: out-of-pocket reduced 26%–35% (covered service not specified) |

China— rural general population (age 12 year and above) |

→ | – | – | – | – | ↓ | ↑ | – | → | Low | |

| Nguyen and Lo Sasso30 | Before: unspecified After: free care at public facilities for inpatient and outpatient services (excluding non-prescription medicines) |

Vietnam— children under age of 6 |

↑ | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | → | Moderate | |

| Sood et al 40 | Before: unspecified After: free tertiary care at the point of service in both private and public hospitals |

India— poor population |

– | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | ↑ | Both increased access to healthcare and reduced out-of-pocket expenditure might have contributed to reduction in mortality | Moderate |

| Ansah et al 39 | Before: unspecified After: free primary care, drugs and initial secondary care on moderate anaemia |

Ghana— rural children age under 5 |

– | → | → | → | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Increased primary care use did not improve health. A possible reason could be that user fees may not be the major financial barrier to care | High |

| McKinnon et al 41 | Before: unspecified After: free deliveries in public, private and facility-based health facilities, covering all normal deliveries, management of assisted deliveries including caesareans, and management of medical and surgical complications of delivery (Ghana) Free deliveries in all public dispensaries and health centres, including all supplies required for delivery. The policy did not initially cover delivery fees in district hospitals and thus did not apply to caesarean sections (Kenya) Covers normal deliveries at health posts and health centres and caesarean sections at district and regional hospitals (Senegal) |

Multi-African countries— women |

– | ↑ | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | Removing user fees increased facility-based deliveries and contributed to reduction in neonatal mortality | Moderate |

| Lamichhane et al 32 | Before: unspecified After: free delivery at public facilities |

Nepal—women (15–49 years old) | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | Reduction in mortality was consistent with the increased use of skilled birth assistance and public facilities for delivery | High |

| Quimbo et al | Before: 49% of total health expenditure paid out-of-pocket After: increase peso ceilings to eliminate copayment for hospitalisation |

Philippines— poor children |

– | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | Low | |

| Rivera-Henandez et al | Before: unspecified After: remove copayment for crucial healthcare services for diagnosis and treatment of diabetes and hypertension |

Mexico—poor population aged 50 and above | – | – | – | ↑/→ | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Moderate | |

| Sosa-Rubi et al 42 | Before: unspecified After: no copayment for specific type of healthcare received |

Mexico— poor population (aged 20–80 years) |

– | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | Decreased user charges increased access to healthcare and improve blood glucose level control | Moderate |

| Tanaka44 | Before: unspecified After: free services to pregnant women included prenatal and postnatal care from confirmation of pregnancy until 42 days after delivery, and all health services to children under 6 years old became free |

South Africa—poor women and children under 6 years old | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | Improved child health status was through increased access to health services | High |

| Increased user charges | |||||||||||||

| Huang and Gan31 | Before: Outpatient care: around 30%–40% of total health expenditure were paid out-of-pocket. Inpatient care: around 20% of total health expenditure were paid out-of-pocket After: Outpatient care: around 86% of total expenditure were paid out-of-pocket Inpatient care: around 28% of total health expenditure were paid out-of-pocket |

China— urban general employees |

→ | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | → | – | Increased user charges decreased outpatient use and expenditure but not for inpatient use and expenditure, and health outcomes | Low |

→, not statistically significant change; ↓, negative change; ↑, beneficial effect on health or increased use/expenditure.

Mortality

Four studies assessed the impact of reducing user charges on mortality (two on neonatal mortality, one on mortality for children under 5 and one on mortality for the total population) in India, Ghana, Nepal and multi-African countries32 39–41 (online supplementary table 3). Most studies included (three out of four studies) found that removing or reducing user charges was associated with reduced mortality. User charge reduction in these three studies applied to tertiary care and maternal care. For instance, McKinnon et al,41 a moderate-quality study, conducted a multicountry analysis in Africa to assess removing user fees from facility-based delivery for women, where they found a 9% reduction in neonatal death as well as a 5% increase in facility-based delivery in the policy countries (Ghana, Kenya, Senegal) compared with the control countries (Cameroon, Congo, Ethiopia, Gabon, Mozambique, Nigeria and Tanzania).

Infectious disease–related outcomes

Three studies assessed the impact of removing user charges on infectious disease–related outcomes (one in Ghana, India and the Philippines, respectively)24 33 39 (online supplementary table 4). Outcomes measured included postoperative infections, malaria-caused parasitaemia and pneumonia, and diarrhoea-related C reactive protein, with mixed results. Improvement in infectious disease–related outcomes was found in two studies assessing the removal of user charges on tertiary care in India and Philippines, while no improvement was found in the study on the removal of user charges for primary care and secondary care in Ghana. Ansah et al, a RCT study, assessed the impact of free primary care, drugs and initial secondary care for children under 5 years old on various health outcomes in Ghana.39 Although this study found that removing user charges had an impact on healthcare use, no significant health benefits were found in the health outcomes assessed, including anaemia, anthropometric measurement, child mortality and parasite prevalence.

Chronic condition–related outcomes

Three studies evaluated the impact of reducing user charge on chronic condition–related outcomes (with two studies in Mexico and one in Ghana)39 42 43 (online supplementary table 5). Outcomes in these three studies included blood glucose control (HbA1c), adherence to medication, diet and exercise for hypertension and diabetes, and anaemia. All three studies found reducing user charges was associated with improved chronic condition–related outcomes. Sosa-Rubi et al, a moderate-quality study, compared enrolees in the Seguro Popular (SP) programme in Mexico, for whom the programme removed copayment for health services for diabetes, with those non-participants where no such benefit was introduced. They found that the SP enrolees had 9.5% greater access to blood glucose control test, 3.1 times more insulin injections and more physician visits than those non-participants, with 5.65 times more likely to appropriately control of blood glucose.

Nutritional and anthropometric outcomes

Two studies reporting nutritional and anthropometric outcomes (one in South Africa and the Philippines, respectively) revealed improved health outcomes with user charges removal for maternal health services and tertiary care33 44 (online supplementary table 6). Outcomes measured included weight:height ratio. Tanaka et al, a high-quality study, examined the removal of user charges for newborns and children in South Africa and found a significant increase in average weight-for-age Z-score for newborns, and weight-for-height Z-score for children, with increased access to health services as the important determinant of nutritional improvement.

Differential impact of user charges and explanatory factors for improvement in health outcomes

The relationship between reduced user charges and improved health outcomes was more evident in studies focusing on children and lower-income populations. Six out of seven studies26 30 32 33 41 44 focusing on children and infants found improved health following a reduction in user charges, including two studies on improved general health, two on reduced neonatal mortality, one on infectious disease–related outcomes and one on nutritional outcomes.

Among the nine studies24 25 27 29 33 40 42–44 evaluating the impact of reducing user charges for the poor (including eight studies on economically poor and one on people working in informal sectors), seven studies (78%) found improved health outcomes following user charges removal. In comparison, of the other eight studies23 26 28 30–32 39 41 focusing on the impact of user charge policy for the general population, five (63%) found improved health outcomes following user charge removal. Two studies assessed and compared the differential effect of user charges by population groups, with mixed findings. One analysis found that the magnitude of reduction in neonatal mortality was larger among women from the lower castes or indigenous ethnic groups,32 while the other study found similar policy effect among various income groups.28

Among the 14 studies reporting healthcare use, 12 found access to and use of healthcare increased following reduction in user charges, and nine further found the increase in healthcare use along with improved health outcomes. Increased access to healthcare due to reduced user charges of care was posited as the possible explanatory factor for better health outcomes in five quasi-experimental studies.29 32 40 41 44 For example, Lamichhane et al, a high-quality study, evaluated the impact of free birth delivery programme on neonatal mortality in Nepal,32 and found a 4%–6.9% reduction in neonatal death in the treatment group compared with control group. The reduced neonatal mortality was consistent with a 6.1%–8.2% increase in women delivering with assistance from skilled birth assistants and an increased use of public facilities, which are possible factors to explain the association between reduced user charges and reduced neonatal mortality.

Discussion

Main findings and interpretation

Our study is the first to examine and synthesise RCT and QE evidence on the relationship between user charges and population health outcomes in LMICs. Our findings are broadly consistent with evidence from HICs which show that user charges may have adverse impacts on health outcomes.11 34–36 45 A systematic review by Goldman et al 36 found that increased cost sharing for prescription drugs was associated with reduced drug treatment and adherence, in particular for chronically ill patients, resulting in more use of expensive medical services such as hospitalisation and emergency visits. This study also suggested that such an adverse effect was likely to be magnified among the poor, who are more price sensitive. However, our study findings contrast with a recent systematic review which focused on maternal health outcomes in LMICs. Dzakpasu et al synthesised evidence and found that reduced user charges were associated with increased facility deliveries, yet with little effect on maternal health outcomes.37 The inconsistency between our study findings on health outcomes is likely due to the broader inclusion criteria by Dzakpasu et al, which included weaker study designs (mainly cross-sectional studies) that are potentially subject to bias. In contrast, our review only included evidence from studies adopting RCT or QE study designs that would reduce bias arising from potential confounders, therefore strengthening causal inference.37

Our review includes several important caveats. First, most studies included here were conducted in middle-income countries, specifically in China, India and Mexico. There were only two studies conducted in low-income countries (Nepal and Senegal). Therefore, it is unclear as to whether the results could be extended in other LMICs at different levels of economic and health system development. Second, a majority of the studies included have a follow-up period of health outcomes of less than 5 years. Future studies should examine the long-term health effects of changes in user charge policies. Although user charges were introduced to raise funding for health systems in several LMICs in 1980s, our review only included one study that evaluated the impact of increased user charges on health outcomes. These may reflect the fact that fewer studies adopted QE study designs until more recently or many user charge policies were not properly evaluated at the time.

Furthermore, the type of evidence contained in RCTs and QEs is unable to support clarity on a range of important questions about the mechanisms by which user fees and health outcomes are inversely related. Likely mechanisms include improved access to effective healthcare and reduced impoverishment from healthcare payments with their associated health effects. But health markets are complex, and the price of accessing public services is only one of a set of key variables in those markets. Implications for the mix of public and private, effective and ineffective and higher and lower priced healthcare options sought, the timeliness of healthcare-seeking decisions and quality of care across all the providers in the market among many other variables are contingent on a host of other contextually specific factors such as the pre-existing public–private mix in any health system, the economic capacity of populations affected, the price levels of other providers and other goods and services, and the regulatory and governance environments. Some measurements of health may not be possible to discern whether user charges had limited effects on health outcomes, or that the conditions measured or the populations studied were not sensitive to the changes.38 Future studies should also use comprehensive measures for patients’ health such as patients’ use of secondary care, clinical and self-reported health outcomes, and mortality rates. Despite the complexity of the mechanisms of effect and the contextual variability of the factors involved, RCTs and QEs suggest quite clearly that user charges are a population health–damaging policy. Few health system policy assessments can produce such a clear result.

Policy and research implications

An important finding of our review is that decreased user charges lead to improvements in health outcomes, especially for children and low-income groups. A potential reason behind this association is that reducing user charges increases access to healthcare. These findings highlight the importance of moving away from user charges to finance UHC, and towards contributory schemes based on prepayment through taxation and insurance contributions with large-scale risk pools that enable cross-subsidisation from the healthy and wealthy to the sick and low-income groups.4

This evidences the importance of public finance for subsidising the costs of healthcare for low-income and disadvantaged populations, and as an effective policy lever to reduce inequities in access and improve health outcomes.4 46 47 While all stand to benefit from enhanced financial protection brought about by greater reliance on prepayment and cross-subsidisation, the lowest-income and less healthy populations will benefit most, as these groups are more likely to face financial hardship due to ill health. Replacing user charges with public funding for these disadvantaged populations should help to reduce financial barriers to accessing care, in turn, improving health outcomes for these groups and promoting equity in health.46 48

Conclusion

In summary, the published evidence to date suggests that reducing user charges is likely to have beneficial effects on health outcomes and reduce health inequalities in LMICs. Our study supports the elimination of user charges for low-income groups and children, and WHO’s call for accelerating progress towards UHC in LMICs.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Valery Ridde

Contributors: JTL contributed to the conception and design of this research. VMQ conducted the data analyses and interpreted the data. VMQ and JTL wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the paper. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings and substantially revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: VMQ is funded by the Graduate Research Scholarship, National University of Singapore. CM is funded by NIHR Research Professorship.

Competing interests: None declared

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Lancet T. Striving for universal health coverage. Lancet 2010;376:1799 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62148-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kieny MP, Bekedam H, Dovlo D, et al. . Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:537–9. 10.2471/BLT.16.187476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Blanc D. Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustainable Development 2015;23:176–87. 10.1002/sd.1582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Etienne C, Asamoa-Baah A, Evans DB. The World Health Report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reeves A, Gourtsoyannis Y, Basu S, et al. . Financing universal health coverage—effects of alternative tax structures on public health systems: cross-national modelling in 89 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2015;386:274–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saksena P, Xu K, Elovainio R. Health services utilization and out-of-pocket expenditure at public and private facilities in low-income countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lagarde MPN. The impact of user fees on access to health services in low and middle-income countries Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. WHO , 2018. WHO global health expenditure atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/en

- 9. Pettigrew LM, Mathauer I. Voluntary Health Insurance expenditure in low- and middle-income countries: exploring trends during 1995–2012 and policy implications for progress towards universal health coverage. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:67 10.1186/s12939-016-0353-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, et al. . Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003;362:111–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rice T, Matsuoka KY. The impact of cost-sharing on appropriate utilization and health status: a review of the literature on seniors. Med Care Res Rev 2004;61:415–52. 10.1177/1077558704269498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. . The oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. Q J Econ 2012;127:1057–106. 10.1093/qje/qjs020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iuga AO, McGuire MJ. Adherence and health care costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2014;7:35 10.2147/RMHP.S19801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mills A. Health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014;370:552–7. 10.1056/NEJMra1110897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Bank , 2016. Country classification. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 16. World Health Organization , 2017. Health financing for universal coverage: WHO. Available from: http://www.who.int/health_financing/topics/financial-protection/out-of-pocket-payments/en/ [Accessed 23 Oct].

- 17. Chiappori P-A, Durand F, Geoffard P-Y. Moral hazard and the demand for physician services: first lessons from a French natural experiment. Eur Econ Rev 1998;42(3-5):499–511. 10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00015-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stock JH, Watson MW. Introduction to econometrics. Updated third edition, global edition Boston: Pearson, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. White H, Sabarwal S. Quasi-experimental design and methods. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterne JAC HM, Reeves BC, Savović J. Risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I): detailed guidance. Bmj 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viswanathan MAM, Berkman ND. Assessing the risk of bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions. agency for healthcare research and quality methods guide for comparative effectiveness reviews, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Diether Beuermann CPG. Inter-American Development Bank The impact of free public healthcare on health status and labor supply in Jamaica, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sood N, Wagner Z. Impact of health insurance for tertiary care on postoperative outcomes and seeking care for symptoms: quasi-experimental evidence from Karnataka, India. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010512 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guindon GE. The impact of health insurance on health services utilization and health outcomes in Vietnam. Health Econ Policy Law 2014;9:359–82. 10.1017/S174413311400005X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nguyen H, Wang W. The effects of free government health insurance among small children—evidence from the free care for children under six policy in Vietnam. Int J Health Plann Manage 2013;28:3–15. 10.1002/hpm.2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bauhoff S, Hotchkiss DR, Smith O. The impact of medical insurance for the poor in Georgia: a regression discontinuity approach. Health Econ 2011;20:1362–78. 10.1002/hec.1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yiqiu Wang MP, Jin S. Estimating effects of health insurance coverage on medical service utilization and health in rural China. Boston, Massachusetts, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aggarwal A. Impact evaluation of India's 'Yeshasvini' community-based health insurance programme. Health Econ 2010;19(Suppl):5–35. 10.1002/hec.1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguyen BT, Lo Sasso AT. The effect of universal health insurance for children in Vietnam. Health Econ Policy Law 2017:1–16. 10.1017/S1744133117000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang F, Gan L. The impacts of China's urban employee basic medical insurance on healthcare expenditures and health outcomes. Health Econ 2017;26:149–63. 10.1002/hec.3281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lamichhane P, Sharma A, Mahal A. Impact evaluation of free delivery care on maternal health service utilisation and neonatal health in Nepal. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:1427–36. 10.1093/heapol/czx124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quimbo SA, Peabody JW, Shimkhada R, et al. . Evidence of a causal link between health outcomes, insurance coverage, and a policy to expand access: experimental data from children in the Philippines. Health Econ 2011;20:620–30. 10.1002/hec.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brook RH, Keeler EB, Lohr KN. The health insurance experiment: a classic RAND study speaks to the current health care reform debate. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mann BS, Barnieh L, Tang K, et al. . Association between drug insurance cost sharing strategies and outcomes in patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e89168 10.1371/journal.pone.0089168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007;298:61–9. 10.1001/jama.298.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dzakpasu S, Powell-Jackson T, Campbell OM. Impact of user fees on maternal health service utilization and related health outcomes: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:137–50. 10.1093/heapol/czs142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:1900–10. 10.1001/jama.298.16.1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ansah EK, Narh-Bana S, Asiamah S, et al. . Effect of removing direct payment for health care on utilisation and health outcomes in Ghanaian children: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000007 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sood N, Bendavid E, Mukherji A, et al. . Government health insurance for people below poverty line in India: quasi-experimental evaluation of insurance and health outcomes. BMJ 2014;349:g5114 10.1136/bmj.g5114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKinnon B, Harper S, Kaufman JS, et al. . Removing user fees for facility-based delivery services: a difference-in-differences evaluation from ten sub-Saharan African countries. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:432–41. 10.1093/heapol/czu027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sosa-Rubí SG, Galárraga O, López-Ridaura R. Diabetes treatment and control: the effect of public health insurance for the poor in Mexico. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:512–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rivera-Hernandez M, Rahman M, Mor V, et al. . The impact of social health insurance on diabetes and hypertension process indicators among older adults in Mexico. Health Serv Res 2016;51:1323–46. 10.1111/1475-6773.12404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanaka S. Does abolishing user fees lead to improved health status? Evidence from post-Apartheid South Africa. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2014;6:282–312. 10.1257/pol.6.3.282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kiil A, Houlberg K. How does copayment for health care services affect demand, health and redistribution? A systematic review of the empirical evidence from 1990 to 2011. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:813–28. 10.1007/s10198-013-0526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gwatkin DR, Ergo A. Universal health coverage: friend or foe of health equity? The Lancet 2011;377:2160–1. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62058-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moreno-Serra R, Smith PC. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? Lancet 2012;380:917–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. WHO Closing the health equity gap: policy options and opportunities for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2018-001087supp001.pdf (234.9KB, pdf)