Abstract

Proper control of mitochondrial function is a key factor in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Mitochondrial content is commonly measured by staining with fluorescent cationic dyes. However, dye staining can be affected, not only by xenobiotic efflux pumps, but also by dye intake, which is dependent on the negative charge of mitochondria. Therefore, mitochondrial membrane potential (Δѱmt) must be considered in these measurements because a high Δѱmt due to respiratory chain activity can enhance dye intake, leading to the overestimation of mitochondrial volume. Here, we show that HSCs exhibit the highest Δѱmt of the hematopoietic lineages and, as a result, Δѱmt-independent methods most accurately assess the relatively low mitochondrial volumes and DNA amounts of HSC mitochondria. Multipotent progenitor stage or active HSCs display expanded mitochondrial volumes, which decline again with further maturation. Further characterization of the controlled remodeling of the mitochondrial landscape at each hematopoietic stage will contribute to a deeper understanding of the mitochondrial role in HSC homeostasis.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are normally quiescent in the bone marrow and for their ATP needs rely predominantly on glycolysis rather than the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle [1–6]. Therefore, mitochondrial volume was widely believed to be low in HSCs, unlike in multipotent progenitor (MPP) cells, which have more respirating mitochondria with higher volumes [7–9]. Mitochondria are negatively charged due to activity of an electron transport chain (ETC) that generates a proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane. This is the direct source of energy for ATP synthesis and leads to the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δѱmt). Mitochondrial volume can be then measured by the distribution of cationic dyes such as MitoTracker, rhodamine 123, and TMRM/TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine methyl/ethyl ester) [10,11]. However, higher Δѱmt in mitochondria reflects a high level of polarization, which increases dye intake and thereby leads to overestimation of mitochondrial volume.

HSCs are also known to exhibit high dye efflux activity, which enables their detection by side-population phenotype [12–14]. Prior to the routine use of HSC markers such as CD150 and CD48 [15,16], it was demonstrated that fumitremorgin C, a specific blocker of the ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2) transporter, did not affect the staining pattern of MitoTracker in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) [4]. A recent study using verapamil, an inhibitor of dye efflux, indicated that HSCs have higher mitochondrial volume than committed cells [17], suggesting that the accurate measure of mitochondrial volume would be provided by a dye-independent method, in which dye intake is not considered because it depends on Δѱmt.

Here, by utilizing an inhibitor of dye efflux, we show that HSCs unexpectedly have higher Δѱmt than MPP and mature hematopoietic cells. Membrane-potential-independent methods demonstrated that the peak of mitochondrial volume occurs during the MPP stage rather than in HSCs or mature cells. Our data suggest that Δѱmt - and efflux-independent methods are required to precisely measure mitochondrial volume in HSCs and their progenies.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (B6-CD45.2) and C57BL/6 mice congenic for the CD45 locus (B6-CD45.1) were purchased from The Jackson Lab-oratory. Mitochondria-targeted green fluorescent protein transgenic (mtGFP-Tg) mice were kindly gifted by Dr. Shitara from the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science [18]. A mixture of mice of both sexes was used for all experiments. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Reagents

FCCP (carbonilcyanide p-triflouromethoxy-phenylhydrazone), oligomycin, polyinosinic−polycytidylic acid (pI:pC), verapamil, and cyclosporin H were purchased from Millipore-Sigma and dissolved in ethanol and water, respectively. TMRM, MitoTracker Orange (MTO), and nonyl acridine orange (NAO) were obtained by Thermo Fisher Scientific and dissolved in DMSO.

Cells

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from embryonic day 13.5 embryos and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

A total of 5000 cells were sorted, centrifuged, and immediately fixed, followed by staining for TEM as described previously [19].

Mitochondrial staining for imaging

Sorted cells were resuspended in 30 µL of StemSPAN (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/mL stem cell factor (PeproTech) and 50 ng/mL thrombopoietin (PeproTech) and then seeded on Lab-Tek II chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coated with Retronectin (Clonetech). Samples were then immunostained as described previously [24]. Rabbit polyclonal anti-TOM20 (FL-145, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, dilution 1:100), mouse monoclonal anti-DNA (AC-30–10, Millipore Sigma, dilution 1:30), or mouse monoclonal anti-ATP5A1 (15H4C4, Invitrogen, dilution 1:100) were used for detection; 2% bovine serum albumin blocking was used to emphasize mitochondrial (mtDNA) over nuclear DNA staining. The amount of DNA per mitochondria was assessed as fluorescence intensity. The resolution limit of confocal imaging does not allow reliable quantitation of nucleoid counts, as reported previously [20]. For TMRM imaging, cells were seeded in StemSPAN medium completed with TMRM 2 nmol/L and verapamil 50 µmol/L.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated and stained for surface markers as described previously [21] (antibodies are listed in Supplementary Figure E1B, online only, available at www.exphem.org). For mitochondrial staining, cells were incubated with MTO, NAO, or TMRM diluted in RPMI or StemSPAN in presence or absence of verapamil 50 µmol/L. MTO and NAO were incubated for 30 min at 37˚C and washed once in 2% FBS−PBS before acquisition. TMRM was incubated for 60 min at 37˚C without washing and then challenged with oligomycin 1 µmol/L or FCCP 1 µmol/L. Samples were acquired on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJo version 12 software (TreeStar). For cell sorting, BM cells were prepared as described above and cells were sorted directly into StemSPAN by a FACS ARIA II cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy

Z-stacks were acquired on a Leica SP5 equipped with 63 × oil immersion lens (numerical aperture 1.4), pinhole set at 1 airy unit with voxel size 80/200 nm on XY/Z. Stacks were deconvolved using the Richardson−Lucy algorithm with the measured point-spread function [22]. Histograms of deconvolved images were stretched to compensate expression-level variations. Tom20 signal was emphasized by a 3D Top Hat filter (8 × 8 × 2 pixel) and then thresholded using supervised Yen (for TOM20) or Isodata (for GFP) algorithms. Cell size was estimated by merging normalized 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Tom20, and DNA signals. Segmented objects were measured for intensity and shape using the 3D suite [23] and then skeletonized to obtain branches length. Representative image renderings were obtained with Imaris 7 software (Bitplane).

Competitive reconstitution assay

Sorted Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated Ly5.1/5.2 congenic mice in competition with BM mononuclear cells from Ly5.2 mtGFP-Tg mice. Reconstitution of donor (Ly5.1) cells and repopulation of donor myeloid and lymphoid cells were monitored by staining blood cells with antibodies against CD45.1, CD45.2, CD3e (T cells), B220 (B cells), CD11b, and Gr-1 (myeloid cells).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Normality assumption was verified with the D’Agostino −Pearson omnibus test. All groups were filtered for eventual outliers using the robust regression and outlier removal method and tested through one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s correction.

Results and Discussion

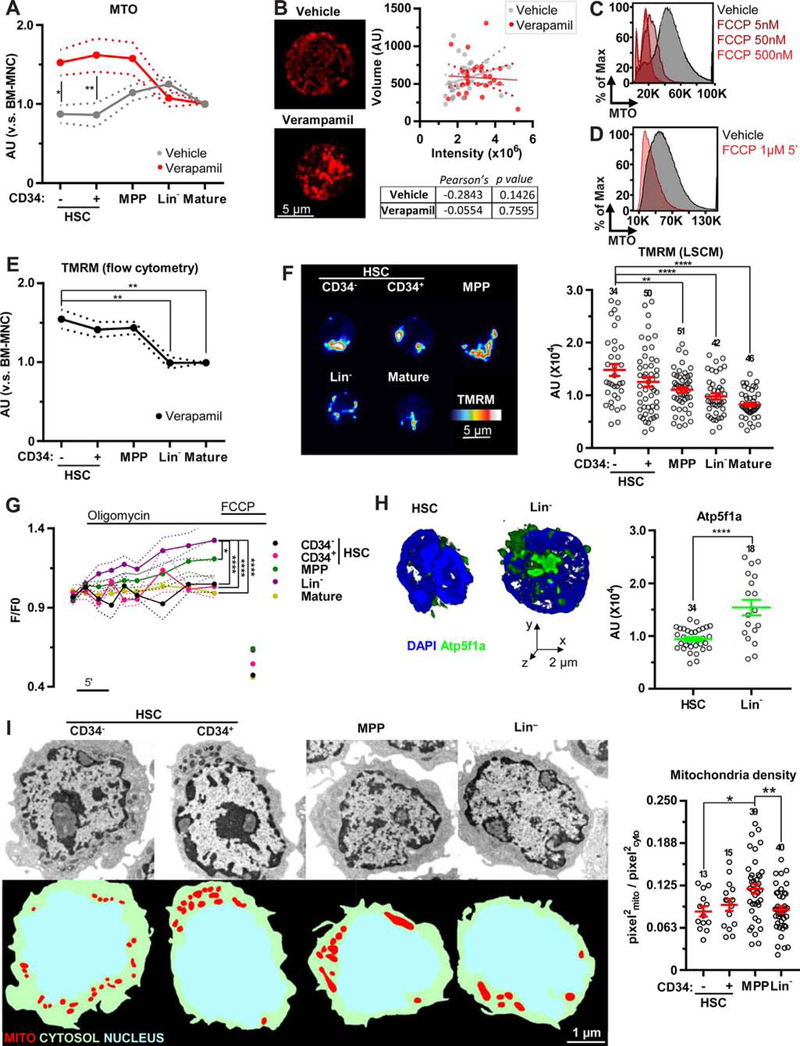

Dye staining can be affected by xenobiotic efflux pumps. In the presence of verapamil, an inhibitor of dye efflux, the staining profile of MTO by flow cytometric assays was changed. Consistent with the high activity of dye efflux in HSCs [17], the pronounced increase in MTO intensity was observed in HSC-enriched fractions (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figures E1A and E1B, online only, available at www.exphem.org). In addition, in the presence of verapamil, a 3D imaging approach did not find a correlation between total MTO intensity and mitochondrial volume (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure E1C, online only, available at www.exphem.org). The intake of cationic dyes, including MitoTrackers, is dependent on the negative charge of mitochondria [10,11]. Exposure to the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP led to a decrease in MTO intensity and, importantly, FCCP addition quickly (~5 min exposure) and substantially reduced MTO intensity in the stained cells (Figures 1C and 1D). Similar results were obtained using another cationic dye, NAO (Supplementary Figures E1D and E1E, online only, available at www.exphem.org). These data suggest that mitochondrial dyes are sensitive to Δѱmt and may not be useful to precisely evaluate mitochondrial content in flow cytometry.

Figure 1.

Elevated Δѱmt in HSC mitochondria. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of MTO in HSPCs and mature BM populations in the absence (grey) or presence (red) of verapamil normalized to bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs). (B) Representative images of BM-MNCs stained with MTO in the absence or presence of verapamil (left); also shown is the correlation between MTO-integrated intensity and mitochondrial volume (right). (C,D) Representative flow cytometric profile of MTO in Lin− cells exposed to the indicated dosage of FCCP before (C) or after (D) MTO staining. (E) Flow cytometric profile of HSPCs and mature BM populations stained with TMRM in the presence of verapamil normalized to BM-MNCs. (F) Representative laser scanning confocal microscopy images (left) and quantification (right) of TMRM staining in HSPCs and mature BM populations. (G) Flow cytometric profile of TMRM intensity in HSPCs and mature BM populations after the addition of oligomycin (1 µmol/L) and FCCP (1 µmol/L). (H) Representative volume rendering and quantification of Atp5f1a expression in HSCs and Lin− cells. (I) Representative TEM images (left, top) and segmentation (left, bottom) of HSPCs and relative quantification of mitochondrial content to cytoplasm area (right). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. At least four mice were analyzed per each experiment and the sample size for each group is shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

We next measured Δѱmt in hematopoietic lineages by the fluorescent dye reporter TMRM. To avoid dye efflux, cells were stained with TMRM in the presence of verapamil or cyclosporine H (a Ca2+-independent multidrug resistance inhibitor) [24] and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Similar to MTO, a higher staining intensity was found in HSC-enriched fractions (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure E1F, online only, available at www.exphem.org) and this was confirmed by laser scanning confocal microscopy analysis (Figure 1F).

Δѱmt is balanced between the activity of the ETC and the proton flux across mitochondrial F1/F0 ATP synthase (hereafter referred as ATP synthase). After the addition of oligomycin (a pharmacological ATP synthase inhibitor), TMRM intensity as measured by flow cytometry was increased in MPPs. This increase was more pronounced in Lin− cells, whereas almost no change was observed in HSCs (Figure 1G). Consistent with these data, Lin− cells expressed higher levels of a key subunit for ATP synthesis, ATP synthase subunit alpha (Atp5f1a), compared with HSCs (Figure 1H). The administration of the ionophore FCCP, which redistributes H+ independently of ATP synthase, was able to drastically reduce the amount of TMRM in mitochondria in all populations, including HSCs (Figure 1G), supporting that the slow activity of electron transport chain in HSCs is still sufficient to generate certain levels of Δѱmt. Our data suggest that HSCs have very low coupling capacity due to the minimum activity of ATP synthesis and, as a result, HSCs show high Δѱmt even though the rates of respiration and phosphorylation are low [25].

Higher Δѱmt in HSCs could increase dye intake, potentially leading to overestimation of mitochondrial volume. To accurately evaluate mitochondrial content, membrane-potential- and dye-efflux-independent methods are needed. Therefore, we first conducted TEM analysis to measure mitochondria density (mitochondria area normalized by cytoplasm area) and found that HSCs have smaller mitochondrial area compared with MPPs (Figure 1I). The mitochondrial density parameter can be used to minimize artifact in a random selection of planes in TEM procedures. Indeed, depending on the position of the selected planes (central or peripheral), the area investigated changes and this can reduce the statistical power of the analysis (Supplementary Figure E1G, online only, available at www.exphem.org).

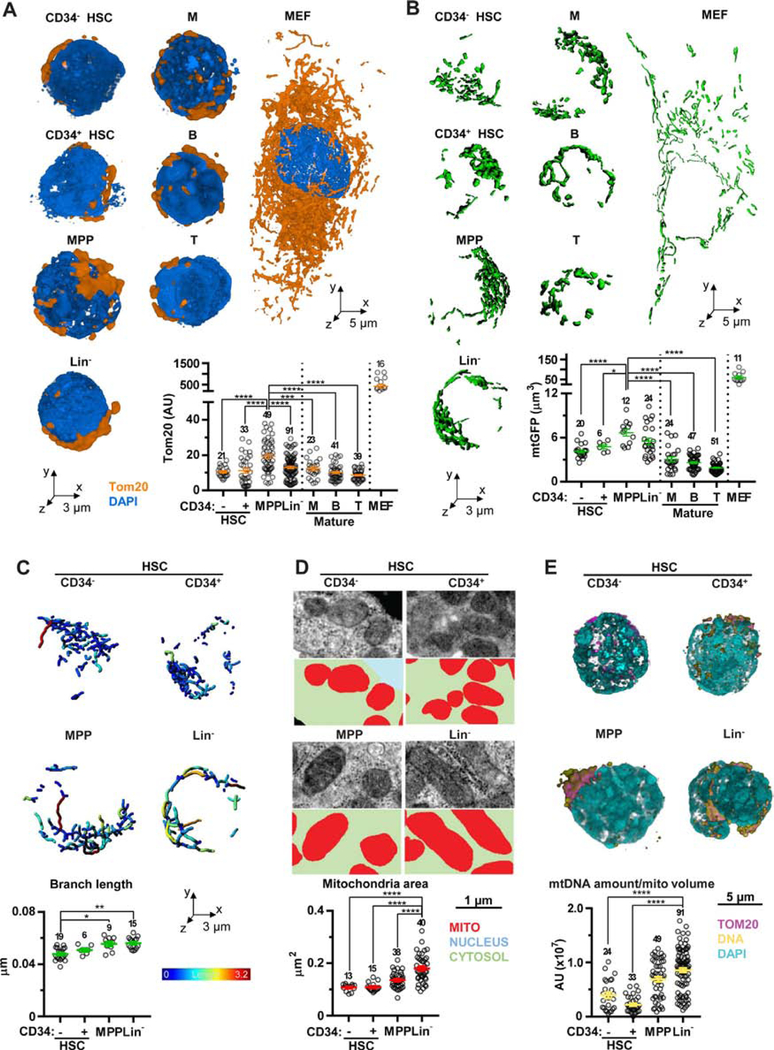

To overcome this limit, we set up a 3D analysis based on immunostaining of the mitochondrial import receptor subunit Tom20 homolog (Tom20) [21,26]. Mitochondria in hematopoietic cells are densely packed around the nucleus (Supplementary Figure E1H, online only, available at www.exphem.org) and their volume is much smaller than stromal cells (e.g., MEFs) in general. However, when comparing among hematopoietic lineages, HSCs showed lower mitochondrial volume compared with MPPs (Figure 2A). To further confirm this observation, a transgenic mouse constitutively expressing mtGFP [18] was used (Supplementary Figure E1I, online only, available at www.exphem.org). GFP-based mitochondrial segmentation also showed the highest volume in MPPs (Figure 2B). Conversely, we could not detect a correlation between mtGFP intensity and mitochondrial content (both obtained by 3D analysis) in HSCs and MPPs (Supplementary Figure E1J, online only, available at www.exphem.org). These data support that mtGFP intensity cannot be used as a reliable marker of mitochondrial content and its intensity fails to distinguish between these two populations, although differences in mtGFP-derived mitochondrial content can be detected by 3D analysis (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure E1J, online only, available at www.exphem.org). In agreement with these results, mtGFPhigh and mtGFPlow fractions flow sorted from HSPCs exhibited similar reconstitution capacity in vivo after transplantation (Supplementary Figures E1K and E1L, online only, available at www.exphem.org).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial remodeling during HSC commitment. (A) Representative volume rendering of Tom20 and DAPI and mitochondrial volume measured by signals of Tom20 in HSPCs, mature BM populations, and MEFs. (B) Representative isosurface rendering of mtGFP and mitochondrial volume measured by signals of mtGFP in HSPCs, mature BM populations, and MEFs. (C) Representative images of skeleton and branch length analyses. (D) Representative TEM images (upper panels) and segmentation (lower panels) of mitochondria from HSPCs and quantification of mitochondrial area (bottom). (E) Representative volume rendering of HSPCs stained for DNA (top) and relative quantitation of DNA average amount normalized on Tom20 staining (mtDNA amount/mitochondrial volume, bottom). Error bars represent mean ± SEM. At least four mice were analyzed in each experiment and the sample size for each group is shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

We next took advantage of mtGFP-expressing cells to deeply investigate the power of 2D analysis of mitochondrial content. Mitochondrial volume was measured in a single plane (2D analysis) for a total of 429 planes for HSCs and 402 for MPPs. By enlarging the amount of planes, this analysis detected statistically significant differences in mitochondrial content between HSCs and MPPs (***p < 0.001; Supplementary Figures E1M, online only, available at www.exphem.org). We also assessed the correlation between the number of planes analyzed and the successful detection of these differences. Specifically, measuring 50 planes failed to detect the discrepancies between these two groups, whereas assessing 100 planes was sufficient to detect these differences (although the p value is < 0.05). These statistical analyses were performed by the non-parametric Wilcoxon test, which is poorly affected by sample size [27], and a sample size of 50 is larger than the 3D analysis performed in this study. These results highlighted the lack of potency of 2D analysis (shared by TEM and immunofluorescence) in spherical cells and the necessity of the analysis taking account of the whole cell by a 3D reconstruction to reliably measure mitochondrial content.

Finally, mitochondrial maturation was assessed. 3D skeleton analysis of mtGFP showed that the shorter branch length was found in HSCs and was increased, along with HSC commitment (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figures E1N, online only, available at www.exphem.org). The average size of single mitochondrial particle obtained by electron micrographs was also increased in mature cells (Figure 2D). Additionally, the amount of mtDNA was analyzed by immunostaining for DNA [28]. HSCs displayed a low mtDNA density (mtDNA amount/mitochondrial volume), whereas Lin− cells displayed the highest (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figures E1O, online only, available at www.exphem.org). These results indicate that mitochondria maturate along with HSC commitment.

Tests that compensate for elevated membrane-potential have shown that mitochondrial volume is relatively low in HSCs and expands at the MPP stage. We believe that our model provides a more accurate picture of mitochondrial content because MPPs require appropriate differentiation potentials in the mitochondria to support cell differentiation [29]. Additionally, we observed that the stimulation of HSCs by pI:pC led to increased mitochondrial volume (Supplementary Figures E1P, online only, available at www.exphem.org) [9,30]. Our data also imply the different mitochondrial contribution between MPP and Lin− stages and it has been shown that these stages undergo remodeling of mitochondria [17]. Part of the mitochondria with impaired respiration can be removed during the differentiation from MPP to Lin− stages, although further investigation will be required to draw solid conclusions.

Our study highlights the usefulness of mitochondrial reporter and 3D analysis of Tom20, which are not affected by membrane potential or efflux, in contrast to mitochondrial dye staining. Mitochondria populations were believed to gradually increase during development from immature to mature cells. However, lower levels of mitochondrial content were observed in mature cells of both myeloid and lymphoid lineages compared with MPPs (Figures 2A and 2B). Importantly, the absolute volume of mitochondria in a cell can be a misleading metric because cell sizes differ among hematopoietic lineages such as myeloid and lymphoid cells. Therefore, Tom20-derived mitochondrial volume was normalized on estimated cell volume to confirm MPP as the fraction with higher mitochondrial density (Supplementary Figures E1Q, online only, available at www.exphem.org). Our in vivo studies have shown that the mtGFPhigh and mtGFPlow fractions from HSPCs have no functional differences. These results imply that the intensity of mtGFP analyzed by flow cytometry is not useful as an HSC marker, but is still useful for image-based content analysis, as evidenced by the high colocalization between mtGFP and TMRM (Supplementary Figure E1I, online only, available at www.exphem.org). ATP synthesis, one of the main regulators of Δѱmt, seems to be non-essential to HSCs, but identifying the specific program that maintains high Δѱmt will reveal further critical functions of HSC mitochondria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the Ito laboratory and the Einstein Stem Cell Institute for comments and the Einstein Flow Cytometry and Analytical Imaging core facilities (funded by National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA013330) for help carrying out the experiments, and the organizing committee for giving us a great opportunity to present our work at ISEH 2018. M.B. thanks Caterina and Leonardo for continuous support. P.P. thanks Camilla degli Scrovegni for continuous support. P.P. is supported by grants from Telethon (GGP15219/B) and the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC: IG-18624) and by local funds from the University of Ferrara. Keisuke Ito is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK98263, R01DK115577, and R01DK100689) and the New York State Department of Health as Core Director of Einstein Single-Cell Genomics/Epigenomics (C029154). Keisuke Ito is a Research Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Broxmeyer HE, O’Leary HA, Huang X, Mantel C. The importance of hypoxia and extra physiologic oxygen shock/stress for collection and processing of stem and progenitor cells to understand true physiology/pathology of these cells ex vivo. Curr Opin Hematol 2015;22:273–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantel CR, O’Leary HA, Chitteti BR, et al. Enhancing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation efficacy by mitigating oxygen shock. Cell 2015;161:1553–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takubo K, Nagamatsu G, Kobayashi CI, et al. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013;12:49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, et al. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2010;7:380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito K, Bonora M, Ito K. Metabolism as master of hematopoietic stem cell fate. Int J Hematol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ito K, Ito K. Hematopoietic stem cell fate through metabolic control. Exp Hematol 2018;64:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suda T, Takubo K, Semenza GL. Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2011;9:298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandel NS, Jasper H, Ho TT, Passegue E. Metabolic regulation of stem cell function in tissue homeostasis and organismal ageing. Nat Cell Biol 2016;18:823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho TT, Warr MR, Adelman ER, et al. Autophagy maintains the metabolism and function of young and old stem cells. Nature 2017;543:205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keij JF, Bell-Prince C, Steinkamp JA. Staining of mitochondrial membranes with 10-nonyl acridine orange, MitoFluor Green, and MitoTracker Green is affected by mitochondrial membrane potential altering drugs. Cytometry 2000;39:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scaduto RC Jr, Grotyohann LW Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent rhodamine derivatives. Biophys J 1999;76:469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, et al. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat Med 1997;3:1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharenberg CW, Harkey MA, Torok-Storb B. The ABCG2 transporter is an efficient Hoechst 33342 efflux pump and is preferentially expressed by immature human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 2002;99:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD, et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat Med 2001;7:1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Yilmaz OH, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 2005;121:1109–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ. SLAM family markers resolve functionally distinct subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2013;13: 102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Almeida MJ, Luchsinger LL, Corrigan DJ, Williams LJ, Snoeck HW. Dye-independent methods reveal elevated mitochondrial mass in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017;21:725–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shitara H, Shimanuki M, Hayashi J, Yonekawa H. Global imaging of mitochondrial morphology in tissues using transgenic mice expressing mitochondrially targeted enhanced green fluorescent protein. Exp Anim 2010;59:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho C, Souza AC, Derengowski Lda S, et al. Macrophage mitochondrial and stress response to ingestion of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol 2015;194:2345–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kukat C, Larsson NG. mtDNA makes a U-turn for the mitochondrial nucleoid. Trends Cell Biol 2013;23:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Turcotte R, Cui J, et al. Self-renewal of a purified Tie2+ hematopoietic stem cell population relies on mitochondrial clearance. Science 2016;354:1156–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sage D, Donati L, Soulez F, et al. DeconvolutionLab2: An open-source software for deconvolution microscopy. Methods 2017;115:28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ollion J, Cochennec J, Loll F, Escude C, Boudier T. TANGO: a generic tool for high-throughput 3D image analysis for studying nuclear organization. Bioinformatics 2013;29:1840–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolli A, Basso E, Petronilli V, Wenger RM, Bernardi P. Interactions of cyclophilin with the mitochondrial inner membrane and regulation of the permeability transition pore, and cyclosporin A-sensitive channel. The Journal of biological chemistry 1996;271:2185–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J 2011;435:297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donato V, Bonora M, Simoneschi D, et al. The TDH-GCN5L1-Fbxo15-KBP axis limits mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2017;19:341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsouaka RA, Betensky RA. Power and sample size calculations for the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test in the presence of death-censored observations. Stat Med 2015;34: 406–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonawitz ND, Clayton DA, Shadel GS. Initiation and beyond: multiple functions of the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Mol Cell 2006;24:813–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue S, Noda S, Kashima K, Nakada K, Hayashi J, Miyoshi H. Mitochondrial respiration defects modulate differentiation but not proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. FEBS Lett 2010;584:3402–3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter D, Lier A, Geiselhart A, et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2015;520:549–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.